Abstract

The principal conditions requiring emergency/urgent intervention in patients with nontraumatic liver lesions are hemorrhage (with or without tumor rupture), rupture of hydatid cysts (with or without infection), complications arising from liver abscesses or congenital liver cysts, rupture related to peliosis hepatis, and in rare cases spontaneous hemorrhage. This article examines each of these conditions, its appearance on ultrasound (the first-line imaging method of choice for assessing any urgent nontraumatic liver lesion) and indications for additional imaging studies.

Keywords: Acute liver disorders, Ultrasound, Contrast-enhanced ultrasound

Sommario

Le principali cause di emergenza/urgenza in patologia epatica non traumatica sono l’emorragia con o senza rottura di neoplasie epatiche, la rottura con o senza infezione delle cisti idatidee, le complicanze degli ascessi epatici, delle cisti congenite del fegato, l’emorragia, la rottura in corso di peliosi epatica e la rara emorragia spontanea. Dopo aver esaminato singolarmente le varie cause di emergenza/urgenza, i rispettivi aspetti ecografici e l’integrazione con altre metodiche di imaging si conclude che nei pazienti con patologia epatica l’ecografia, con o senza mezzo di contrasto, è la metodica da utilizzare in prima istanza ad ogni emergenza/urgenza non traumatica del fegato.

Introduction

The principal conditions requiring emergency/urgent intervention in patients with nontraumatic liver lesions are hemorrhage (with or without tumor rupture), rupture of hydatid cysts (with or without infection), complications arising from liver abscesses or congenital liver cysts, rupture related to peliosis hepatis, and in rare cases spontaneous hemorrhage.

Spontaneous hemorrhage

Spontaneous liver hemorrhage is caused by improper use of anticoagulant agents (e.g., coumarin derivatives or heparin) or, less frequently, of drugs that inhibit platelet aggregation. The symptoms are pain, pallor, general malaise, and progressively severe anemia. Ultrasound reveals only the presence of liquid in the perihepatic region and Morrison’s pouch and later free fluid among the loops of the intestine, without any indication of the cause.

Acute events related to pre-existent liver lesions

When there is no history of trauma, anticoagulant drug therapy, or gynecological disease, the presence of hemoperitoneum should always raise the suspicion of spontaneous hemorrhage from a liver lesion. Liver tumors that are subject to rupture and hemorrhage can be malignant (hepatocellular carcinoma, liver metastases) or benign (adenoma, angioma, focal nodular hyperplasia). Rarer causes include liver abscesses, parasitic and nonparasitic cysts, peliosis hepatis, amyloidosis, and the pre-eclamptic HELLP syndrome, which is characterized by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and a low platelet count.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common cause of cancer-related death in the world (1,300,000 cases/year). Death can be caused by liver failure, neoplastic cachexia, bleeding esophageal varices, and in rarer cases, tumor rupture with hemoperitoneum. A recent estimate based on various sources, including a report by the World Health Organization, placed HCC-related mortality rates for 2009 at 4/100,000 inhabitants for males and 1/100,000 for females, 34 and 41 % lower than the rates recorded for the year 2000. However, the annual incidence/mortality ratio is only slightly higher than 1 (~1.3), which reflects the high short-term mortality associated with this primary liver tumor (94 % in some parts of the world).

In most cases, the disease is characterized by the presence of one or more nodules or diffuse disease, which recurs or spreads within the liver, invading the hepatic ducts and/or portal system. It can also be associated with lymph node metastases; diffuse metastatic disease is rare and frequently involves the bones (20 %). The prognosis depends on the patient’s liver function and the stage of the disease.

HCC rupture is a common cause of hemoperitoneum (24 %), second only to gynecologic disorders. Tumors characterized by progressive growth and/or subglissonian locations are at high risk for rupture [1]. In areas like Asia or Africa, where the incidence of HCC is high, rupture is a common presenting symptom (11–26 % as compared to 2–3 % of cases diagnosed in Spain and Italy) [2–4]. The incidence of spontaneous HCC rupture ranges from 4.7 to 10 %, and it is the cause of 10 % of all HCC-related deaths. Post-rupture survival ranges from 13 days in patients treated with conservative measures alone to 98.5 days for those who undergo embolization.

Rapid growth of an HCC can cause degeneration and necrosis leading to hemorrhage, which is probably caused by vascular damage secondary to breakdown of type IV collagen and loss of elastin. This chain of events generally precedes rupture of the tumor itself [1, 3].

Massive intralesional hemorrhage increases the pressure within the tumor, and if the lesion is subcapsular, this can provoke rupture and bleeding into the peritoneal cavity.

Spontaneous rupture is diagnosed clinically in the presence of right upper quadrant pain, rapidly progressive anemia, and/or shock. In these cases, ultrasound reveals a large (>5 cm in diameter) inhomogeneous focal lesion in a patient with a history of cirrhosis, which is also obvious on imaging studies. The ruptured tumor is often subcapsular, and ultrasound discloses the presence of particulate ascites [4–6]. In this case, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) should be done: it can confirm the presence of an HCC and demonstrate extravasation of the contrast medium into the high-density ascites fluid surrounding the lesion. Second-generation contrast-enhanced ultrasound may also be useful. It can demonstrate the presence of necrotic tissue within the tumor, which extends to and penetrates the Glisson capsule; in some cases, contrast medium will also be observed within the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 1a, b).

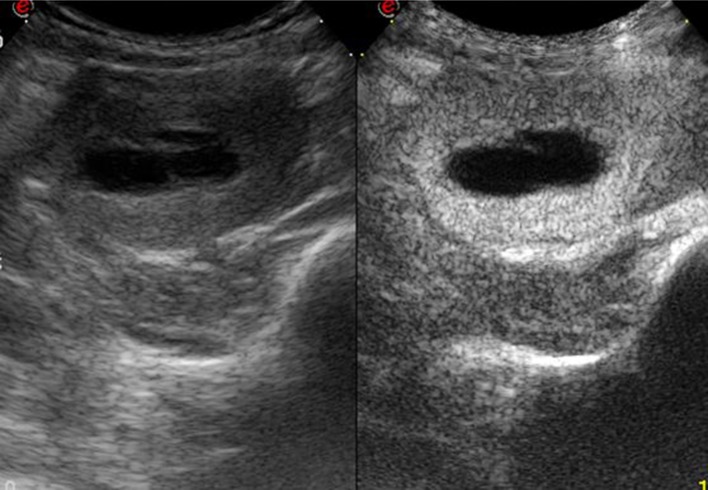

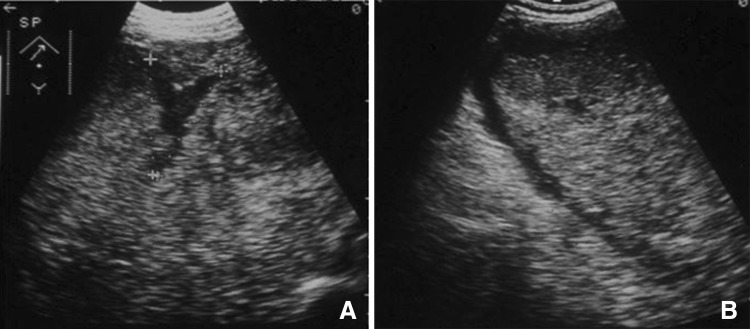

Fig. 1.

Ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Large, inhomogeneous lesion located in the left lobe of the liver in a patient with cirrhosis (a). Administration of Sonovue (b) reveals avascular areas within the lesion characterized by little or no contrast medium

Hepatic adenoma

Hepatic adenomas are rare benign tumors that can arise from either the bile ducts or liver cells. In the former case, the tumor is generally small and clinically irrelevant; the latter form can reach diameters of 10–15 cm and has an important clinical impact.

These tumors are more common in women currently on estrogen–progestin therapy (4 cases × 100,000 versus 1 case × 1,000,000 in those who have not used these drugs for 2 years or more).

Their incidence is also increased in patients with diabetes, hemochromatosis, or acromegaly, and in men who take anabolic steroids.

Hepatic adenomas can rupture and bleed, causing pain in the right upper quadrant and in rare cases hemorrhagic shock. Rupture occurs in up to 30 % of all cases, and it is the main reason for surgery in patients with these tumors (17 %). Adenomas can also undergo neoplastic transformation, although the frequency of this complication is unknown [7].

The term hepatic adenomatosis is used to refer to the presence in the liver of 10 or more adenomas. This rare condition is associated with a high risk of complications, especially tumor rupture. Pain is reported by 87.5 % of patients with adenomatosis and 42.1 % of those with a solitary adenoma; rates of rupture with hemorrhage in these two groups are 62.5 and 26.3 %, respectively. Hemorrhage always occurs with lesions that are >4 cm in diameter.

Rupture of a hepatic adenoma is initially manifested by pain and later, if hemoperitoneum develops, by progressive anemia and hemorrhagic shock. Ultrasound reveals a large (>4–5 cm), subcapsular nodule with an inhomogeneous echostructure that was not present on previous studies. The nodule expands progressively toward the surface of the adenoma, and in some cases, free fluid with a corpuscular aspect is observed in the peritoneum. In these cases, contrast-enhanced ultrasound is particularly useful: it will demonstrate a breach in the liver capsule and the presence of an avascular intralesional area that may extend all the way to the surface of the adenoma (Fig. 2). Computed tomography findings are similar to those in patients with HCC [8].

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging of a focal liver lesion revealed a hepatic adenoma containing avascular areas caused by tumor rupture

Hepatic angioma

Hepatic angiomas are the most common benign liver tumor (20 %). Most of these lesions, even when large, are asymptomatic (85 %), but in rare cases they are associated with compression of adjacent structures, rupture, acute thrombosis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (Kasabach–Merritt syndrome).

Giant angiomas of the liver—the ones associated with complications—are diagnosed sonographically, a process that has been facilitated by the recent introduction of acoustic contrast media.

Angioma-related compression of the inferior vena cava can lead to the Budd–Chiari syndrome. The diagnosis can be made rapidly with color Doppler demonstration of the absence of vascular signals in the hepatic veins. Even more effective is CEUS, which shows no enhancement of the hepatic veins and inferior vena cava.

Massive, acute thrombosis of an angioma is associated with pain and fever. B-mode ultrasound reveals only nonspecific increases in the size and inhomogeneity of the lesion, whereas CEUS and CT demonstrate a large avascular area (Fig. 3a, b).

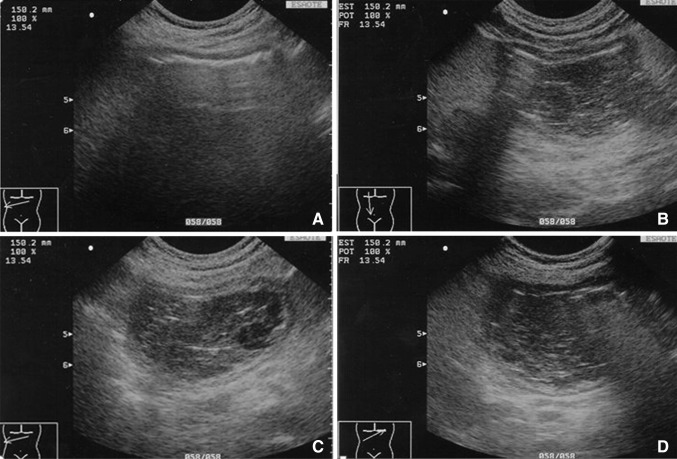

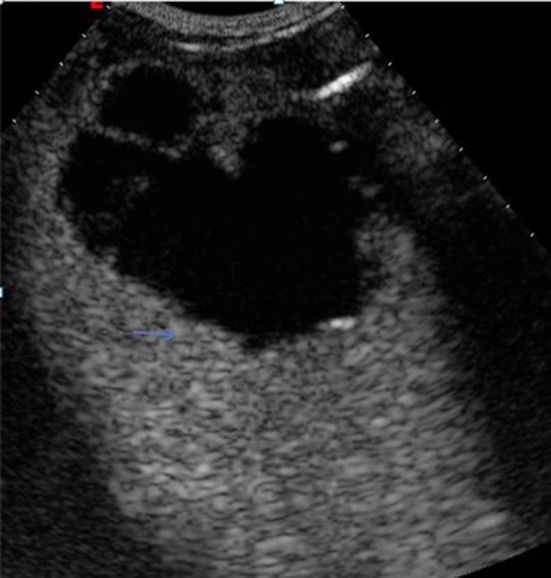

Fig. 3.

Large angioma of the right lobe of the liver in a patient hospitalized for intense right hypochondriac pain (a). CEUS reveals large avascular areas caused by acute thrombosis (b)

Rupture is rare and seen only with large angiomas, which account for 1–4 % of all benign vascular lesions of the liver. When it occurs, the mortality rate is very high (60 %) [9, 10].

B-mode ultrasound may reveal free liquid in the peritoneum and alterations within the lesion (Fig. 4a, b), but CEUS and CT will show an avascular area extending all the way to the liver capsule and in some cases extravasation of contrast medium into the peritoneal cavity [11].

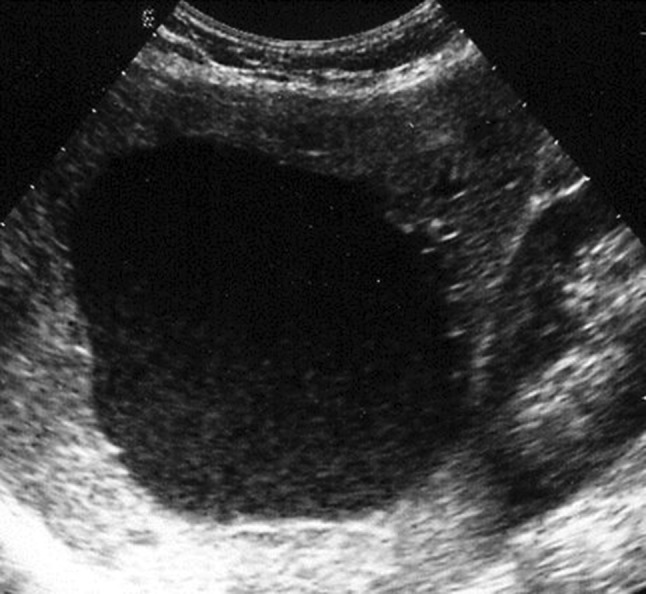

Fig. 4.

Rupture of a giant angioma. The large inhomogeneous lesion that occupies the entire right lobe of the liver represents a giant angioma with a V-shaped anechoic area that extends all the way to the Glisson capsule (a). Perihepatic liquid represents blood in the peritoneum (b)

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH)

FNH probably represents a reaction of the liver tissue to the presence of a vascular malformation. It accounts for 8 % of all hepatic tumors, and its incidence in the pediatric population is 4 %. It is generally characterized by a solitary lesion with a diameter anywhere from 5 mm to 20 cm, although in 85 % of all lesions measure <5 cm.

There are no reports of spontaneous complications that led to death; mortality is related exclusively to surgical treatment. Focal bleeding and infarction are occasionally seen in FNH, particularly in women on estrogen–progestin therapy. If these drugs are not being used and the patient is not pregnant, there is virtually no risk of rupture: all complications reported in the literature have occurred exclusively in these risk groups [12, 13].

Peliosis hepatis

Peliosis hepatis is a rare benign liver disorder characterized by irregular, oval-shaped blood-filled lesions lined with hepatocytes or endothelial cells. The lesions, which range in size from 1 mm to several centimeters, communicate with the sinusoids (often dilated), and they can involve most of the liver. The cavities are caused by obstructed blood flow at the sinusoidal level secondary to necrosis or direct damage to the sinusoidal barrier.

Peliosis hepatis is more common in individuals who take anabolic steroids, cortisone derivatives, or oral contraceptives and in those with chronic diseases, tumors, tuberculosis, kidney or heart transplants, diabetes, Hodgkin’s disease, or the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. It is often an occasional finding during ultrasound and/or CT performed for other reasons. In rare cases, it may cause liver failure, cholestasis, portal hypertension, or spontaneous rupture of the liver.

Fatal cases have been described, which are frequently associated with congenital disease, but spontaneous arrest of the hemorrhage has also been reported [14, 15].

Liver metastases

From 25 to 50 % of patients with solid tumor malignancies have liver metastases at the time of diagnosis. In these cases, the primary tumor is usually located in the gastrointestinal tract (60 %), pancreas (20 %), breast (10 %), or lung (10 %). Most liver metastases cause death by producing progressive liver failure.

Emergencies related to liver metastases are rare and generally caused by neoplastic infiltration of the Glisson capsule, which can cause intense pain and rupture with blood and bile in the peritoneum. Rupture of a metastatic lesion (generally subcapsular) is the result of congestion of the hepatic veins and necrosis. It is especially frequent following chemotherapy.

Rupture has been reported with metastases originating from carcinoma of the lung, colon, kidney, pancreas, testis, melanomas, and tumors of the head, neck, and breast.

Liver abscesses

The complications associated with pyogenic or amebic abscesses of the liver are mainly vascular or related to rupture into pleural, peritoneal, pericardial, or retroperitoneal space, the gastrointestinal tract, and/or the bile ducts. The rate of complications is as high as 21 % in some series (13.5 % for pleuropulmonary complications, up to 3.6 % for vascular complications, and generally no more than 1.2 % for ruptures involving the peritoneal or pericardial space, the bile ducts, or the gastrointestinal tract).

The likelihood of rupture depends on several factors, including:

The size of the abscess: rupture is very rare when the lesion measures <5 cm, more common with diameters of 5–10 cm, and high when the lesion is more than 10 cm

Location: rare in intraparenchymal lesions and considerably more common in subcapsular abscesses or those in close contact with vascular or biliary structures

Lack of response to medical therapy

Lack of response to ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage

Amebic abscesses can also rupture into the pleural cavity/lungs, or the peritoneal or pericardial space, with mortality rates of 6, 18, and 30 %, respectively.

In the preantibiotic era, 28 % of all liver abscesses (pyogenic or amebic) were complicated by rupture and/or extension into other organs. The frequency of these events dropped markedly after antibiotic therapy was introduced (5.4 %), but they can still be associated with high mortality (15.5 versus 43.5 % before antibiotics were available).

Rupture of pyogenic liver abscesses has been rare in the ultrasound era: in most case series, there are no cases at all (0–2.4 %), but in many others rupture rates range from 10 to 12 %.

The risk of rupture in amebic abscesses also depends on whether or not they are treated: without drainage or ultrasound-guided aspiration, the incidence of rupture can be as high as 2.04 % with pleural complications in 18.36 %. When these abscesses are drained or aspirated, the rate of rupture drops below 0.5 % and reaches 0 % in some series.

Rupture should be suspected when there is a decline in the general condition of the patient accompanied by pain and/or shock [16]. B-mode ultrasound often reveals a subcapsular lesion measuring more than 5 cm in diameter, interruption of the liver capsule, particulate liquid in the perihepatic area, and later free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. When the abscess ruptures into the peritoneal cavity, its size decreases.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound is superior for detecting ruptures since it can reveal interruption of the capsule, the perihepatic fluid collection (Fig. 5), and the presence of a pleural or pericardial fluid collection, but CT is indicated when a complicated abscess is suspected [17].

Fig. 5.

Spontaneous rupture of a liver abscess. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the liver in a patient with a liver abscess shows an avascular area representing the abscess, interruption of the liver capsule, and a small fluid collection around the Glisson capsule (arrows)

Congenital hepatic cysts

The most frequent complications associated with congenital nonparasitic hepatic cysts are pain (secondary to distention of the Glisson capsule), hemorrhage, infection, spontaneous rupture, jaundice, cholangiocarcinoma, and peduncular torsion. In some series, the global incidence is <0.01 %. The most common is spontaneous intracystic hemorrhage, which rarely constitutes a true emergency.

In these cases, B-mode ultrasound discloses an increase in cyst volume and the appearance of fine echoes that are stratified posteriorly (Fig. 6). In the days that follow, these alterations may disappear or persist with the development of fibrin pseudosepta or in rare cases round images representing blood clots. In these cases, doubts can be resolved with the use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound: in patients with nonparasitic cysts who present with intense pain, the scan reveals a completely avascular lesion.

Fig. 6.

Large, nonparasitic liver cyst with fine, stratified echoes posteriorly representing spontaneous intracystic hemorrhage

Spontaneous rupture of a congenital nonparasitic cyst is extremely rare. It should be suspected, however, when patients with giant complex nonparasitic cysts present with intense pain and free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. In these cases, too, CEUS or contrast-enhanced CT can be useful.

Hepatic echinococcosis

Human echinococcal cysts can rupture during the phase of active growth, when the intracystic pressure may exceed 80 cm H2O. The rupture initially involves the hydatid membrane, then the pericyst, and later extend to the adjacent vascular, biliary, and/or bronchial structures and the parenchyma of the affected organ. Ruptures are the only true complication associated with these cysts. They can be divided into three types:

Contained ruptures: the breach is restricted to the cystic membranes; the contents of the cyst remain confined within the pericyst

Communicating rupture: rupture of the pericyst leads to drainage of the cyst contents into the biliary or bronchial tree

Direct: rupture of the membranes and the pericyst leads to the direct spillage of the cyst contents into the peritoneal cavity or the pleural or pericardial space

Contained ruptures cause allergic manifestations and in rare cases infection of the cyst itself. Communicating ruptures can cause acute obstruction and infection of the bile ducts. Direct ruptures may be followed by anaphylactic shock and in the months that follow ultrasound evidence of colonization of the serous cavities [18]. The urgency of these events is related to the risk of sepsis secondary to infection of the cyst cavity (contained and communicating ruptures), biliary colic with or without jaundice (communicating rupture into the bile ducts), and anaphylactic shock (direct rupture).

B-mode ultrasound is the first-line method of choice for diagnosing complications of hydatid cysts. It shows the double-walled structure of the cyst in contained ruptures, and in the presence of communicating ruptures, the heterogeneous echostructure of the cyst (with or without the water-lily sign); and dilatation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts, with or without echogenic material in the gallbladder, which will be associated with biliary colic, jaundice, and/or fever [19]. The ultrasound appearance of a suppurated echinococcal cyst is characterized by internal inhomogeneity, sometimes accompanied by reverberation artifacts if the infection is caused by gas-producing bacteria (Fig. 7). Direct rupture is reflected on ultrasound by the presence of particulate fluid in the peritoneal cavity or the pleural or pericardial space, which may or may not contain tiny daughter cysts. The cyst itself (in general a subcapsular lesion located in the periphery of the liver) will appear smaller than at previous studies.

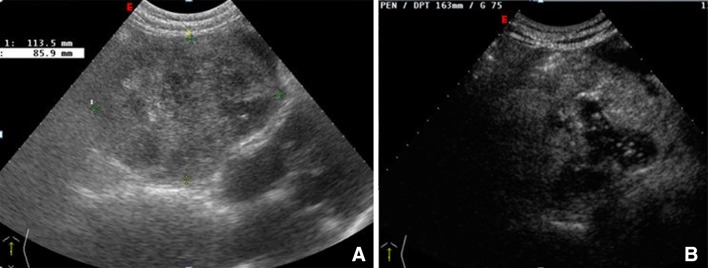

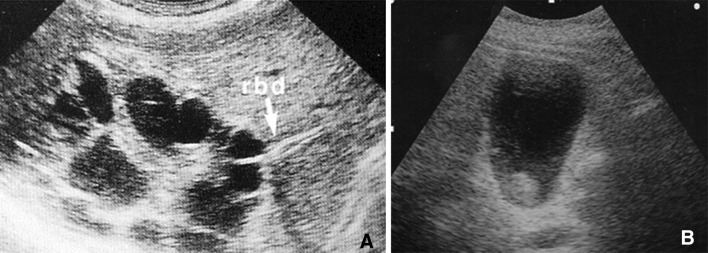

Fig. 7.

Suppuration of a hydatid cyst caused by gas-producing microbes. Complex hepatic lesion with internal reverberation artifacts (a). b, d Small daughter cysts and the wall of the lesion itself can also be seen (c)

Rupture of a hydatid cyst should be suspected in the presence of cystic lesions in direct contact with large bile ducts, which may be dilated (at the intra- and extrahepatic levels); echogenic material without posterior shadowing in the bile ducts and/or gallbladder (Fig. 8); rapid loss of homogeneity in the cyst contents; or free liquid in the peritoneal cavity in a patient with large subcapsular cystic lesions. CT is the method of choice for confirming the presence of these complications.

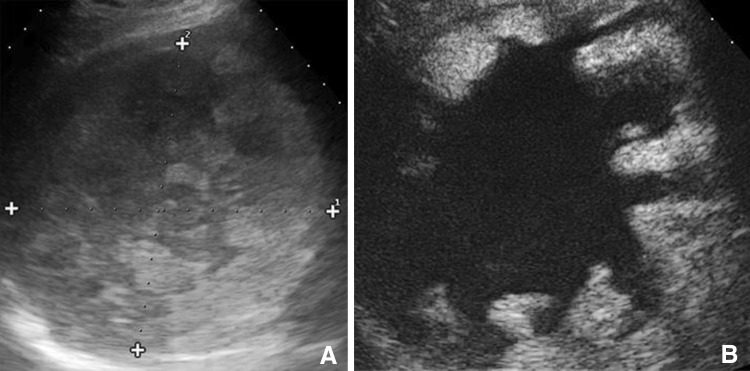

Fig. 8.

Rupture of a hydatid cyst in the bile ducts. The large hydatid cyst is in contact with the right bile duct (a). The main bile duct and the gallbladder both contain echogenic material without posterior shadowing (b)

Conclusions

In patients with liver disorders, ultrasound, with or without contrast enhancement, is the first-line imaging method of choice for workup of nontraumatic hepatic emergencies.

Conflict of interest

Marcello Caremani, Danilo Tacconi and Laura Lapini declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this paper.

Informed consent

No patient information is included in this study.

Human and animal studies

This article does not contain any studies involving human or animal subjects performed by the author.

References

- 1.Yeh CN, Lee WC, Jeng LB, Chen MF, Yu MC. Spontaneous tumor rupture and prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2002;89(9):1125–1129. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vergara V, Muratore A, Bouzari H, Polasti R, Ferrero A, Galatola G, Capussotti L. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: surgical resection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26(8):770–772. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2000.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vivarelli M, Cavallari A, Bellusci R, De Raffele E, Nardo B, Gozzetti G. Ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma:an important cause of haemoperitoneum. Eur Surg. 1995;161(2):881–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CY, Lin XZ, Shin JS, Lin CY, Leow TC, Chen CY, Chang TT. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21(3):238–242. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199510000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu LX, Wang GS, Fan ST. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1996;83(5):602–607. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Battula N, Madanur M, Priest O, Srinivasan P, O’Grady J, Henegan MA, Muiesan P. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective review. Am J Surg. 2000;197(2):164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faria SC, Iyer RB, Rashid A, et al. Hepatic adenoma. AJR. 2004;182(6):1520. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.6.1821520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussain SM, Van den bos IC, Dwarkasing RS, et al. Hepatocellular adenoma: findings at state of art magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound, computed tomography and pathologic analysis. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(9):1873–1886. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoyo T, Kawarada Y, Yano T, Noguchi T, Mizumoto R. Spontaneous rupture of hemangioma of the liver: treatment with transcatheter hepatica arterial embolizzation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1645–1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajneesh KS, Sorbh K, Peush S, Tushar KC. Giant haemangioma of the Liver: is enucleation better than resection. Ann R Coll Sur Engl. 2007;89(5):490–493. doi: 10.1308/003588407X202038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohan S, Gupta A, Verma A, Kathura MK, Baijal SS. Case report: non surgical management of giant liver hemangioma. Ind J Radiol Imaging. 2007;17(2):81–83. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.33616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrnes V, Cardenas A, Afdhal N, Hanto D. Symtomatic focl nodular hyperplasia during pregnancy: a case report. Ann Hepatol. 2004;3(1):35–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Stasi M, Caturelli E, De Sio I, et al. Natural history of focal nodula hyperplasia of the liver. An ultrasound study. J Clin Ultrasound. 1996;4:345–350. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0096(199609)24:7<345::AID-JCU3>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanoff M, Rawson AJ. Peliosis hepatis. An anatomic study with demonstration of two varieties. Arch Pathol. 1964;77:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavalcanti R, Pol S, Carnot F, Campos H, Degott C, Driss F, Legendre C, Kreis H. Impact and evolution of peliosis hepatis in renal transplantation recipients. Transplatation. 1994;58(3):315–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.el Khatib CM. Spontaneous rupture of primary pyogenic liver abscess. J R Soc Med. 1986;79(9):547–548. doi: 10.1177/014107688607900919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou FF, Sheen-Chen SM, Lee TY. Rupture of pyogenic liver abscesses. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(5):767–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewall DB, Mc Corkell SJ. Rupture of echinoccal cyst: diagnosis, classification and clinical implications. AJR. 1986;146:391–394. doi: 10.2214/ajr.146.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murty TVM, Sood KC, Fawzi SR. Biliary obstruction due to ruptured hydatid cyst. J Ped Sur. 1989;24:401–403. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(89)80281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]