Abstract

Spontaneous migration of a retained bullet is rare. We are presenting here a case of a 24-year-old male with spontaneous migration of bullet from arm to forearm. At the time of initial injury, bullet was left inside the arm as it was deep and patient had no complaints. Three months after injury, he started complaining of pain over forearm and tingling sensations in the forearm and hand over median nerve distribution. Radiographs showed bullet in the proximal forearm. The bullet was than precisely localized and removed under ultrasound guidance. This case report emphasizes the fact that spontaneous migration of bullet in extremities may occur and have the potential to cause neurovascular damage. Removal under ultrasound guidance is a viable option in such locations.

Keywords: Arm, Bullet, Spontaneous migration

Sommario

La migrazione spontanea di un proiettile trattenuto è rara. Presentiamo il caso di un paziente maschio, di 24 anni di età, con migrazione spontanea di una pallottola dal braccio all’avambraccio. Al momento iniziale, il proiettile era stato lasciato all’interno del braccio perchè in sede profonda in paziente con scarsa resistenza al dolore. Tre mesi dopo, questi ha iniziato a lamentare dolore al l’avambraccio e sensazioni di formicolio a braccio e mano, nelle aree innervate del nervo mediano. Le radiografie hanno mostrato il proiettile nell’avambraccio prossimale. Il proiettile veniva localizzato con più precisione e rimosso sotto guida ecografica. Questo caso sottolinea il fatto che la migrazione spontanea di un proiettile nelle estremità può verificarsi ed è potenzialmente causa di danni neurovascolari. In tale situazione la rimozione sotto guida ecografica è una valida opzione.

Introduction

Migration of a bullet to a distant part of the body after gunshot injury is rarely observed. This migration may sometimes lead to neurovascular injury. We report a case of spontaneous migration of bullet from the arm to the forearm 3 months after a gunshot injury. The retained bullet started to cause irritation of median nerve leading to tingling sensation over the distribution of median nerve. The bullet was precisely localized and removed under ultrasound guidance.

Case report

A 24-year-old man presented to us with gunshot injury to right arm. The injury was 6 h old at time of presentation. The patient had a history of sustaining the injury with a revolver while he was trying to run away from the shooter. He was fired from a distance of 4 feet. At presentation in the emergency department, he was conscious, oriented and cooperative. Patient was ambulatory and all vital signs were stable.

On physical examination there was a single entry wound on anteromedial aspect of right arm, 5 cm distal to the axilla. There was no exit wound. The skin next to the entry wound was swollen, but there was no active bleeding. He was moving his arm, forearm and wrist with full range of motion and there was no distal neurovascular deficit. There was no clinical evidence of any fracture in the upper limb. In the radiographs, the bullet was located in the upper arm (Fig. 1). As the bullet was located deep and the patient had no complaints, so it was decided not to remove the bullet. After a thorough lavage and debridement of wound under local anesthesia, the wound was left open. The patient was discharged on oral antibiotics. Wound gradually healed within a span of 10 days.

Fig. 1.

Radiographs of the arm taken after the injury showing bullet inside the proximal arm

The patient then underwent regular outpatient examinations and there were no fresh complaints. Three months later patient visited us with complaint of pain over proximal forearm. He also complained of tingling sensations over the volar aspect of forearm and first three digits of the hand. There was no associated motor weakness. Radiographs of the forearm were done and bullet was found in proximal end of forearm (Fig. 2). A decision was to remove the bullet. Position of bullet was initially confirmed with portable ultrasound machine (Micromaxx, Sonosite Inc, USA) with 7.5 MHz straight probe (Fig. 3). Ultrasound-guided extraction of bullet was then done. Immediately after removal of bullet, his pain decreased significantly and the tingling sensation gradually disappeared within a period of 1 week. Follow-up after 2 weeks was uneventful with complete relief in pain and tingling sensations. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and its accompanying images.

Fig. 2.

Radiographs taken after 3 months of the injury showing migration of bullet in the proximal forearm

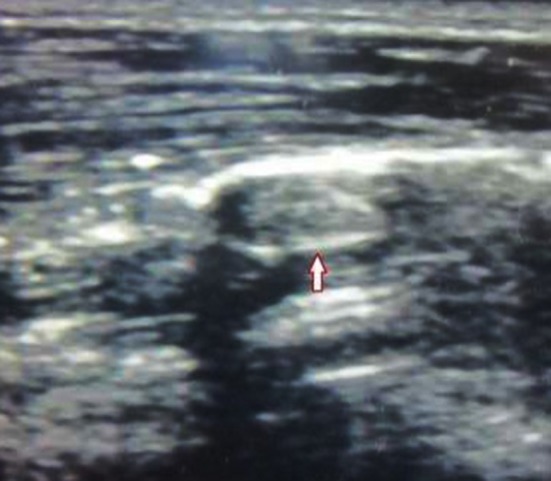

Fig. 3.

Ultrasonographic localization of the bullet (bullet marked with arrow)

Discussion

Migration of a bullet from its initial site to a distant site has rarely been reported. If imaging techniques fail to find bullet at the site of injury then migration in the body should be considered [2]. A bullet may migrate via several routes. It may migrate locally along intermuscular space or may migrate along vein or artery to a distant site. Ceylan et al. [3] reported a case of bullet migration following gunshot injury to the abdomen. Colquhoun et al. [2, 4] reviewed cases of bullet migration after air gun pellet injuries where in 85 % of cases, the bullets migrated along arteries, and in 80 % of cases they migrated along veins. Schmelzer et al. [10] suggested that if a bullet migrated in a vein to the heart, it could further migrate along the aorta and major arteries to other arterial branches and could cause arterial embolism in lower limbs. Morton et al. [9] described three cases in which bullets migrated from liver, vena cava, and a major vein of the lower trunk to the right ventricle or pulmonary artery. In addition to migration along the direction of blood flow, retrograde (i.e. against the blood flow) bullet migration in the venous system, although exceedingly rare, has also been reported. Michelassi et al. [8] reported that the probability of retrograde venous migration is about 15 %, with possible migration from venous system to arterial system, typically as a result of arteriovenous fistula, ventricular septal defect, or atrial septal defect.

A case was reported in which bullet reached knee joint 4 years and 6 months after the bullet was initially localized in distal third of thigh. Clinically, the patient presented with symptoms of a loose body and radiography showed an intra-articular metallic object [6].

In our case, the bullet migrated along the intermuscular route and was impinging on median nerve which leads to pain and tingling sensations on the volar aspect of forearm and first three digits of the hand. There was no associated motor weakness. As the incision was small, no attempt was made to identify median nerve. The treatment for bullet retention and migration is inconclusive. Bullets remaining in the human body may cause various complications, such as pain, local paresthesia, claudication, gangrene, bullet-induced toxicity, thrombophlebitis, pericardial/pleural effusion, pulmonary abscess/infarction, endocarditis, arrhythmia, false aneurysm, septicemia, cerebral infarction, and mental abnormalities. Shannon et al. [11, 12] reviewed 102 cases of gunshot injuries, and found that a bullet retained in a blood vessel was associated with complication incidence of 25 % and death rate of 6 %. However, the incidence of complications is reduced to 1–2 %, if the bullet is removed. Therefore, they recommended surgical removal of the bullet. Barrett et al. [1] also suggested that removing the bullet might prevent complications resulting from vascular embolism.

Ultrasound can be used effectively to find foreign bodies as small as 2.5 mm in length [5, 7]. The easy availability of ultrasound in the emergency department makes it an excellent modality for localization and subsequent removal under its guidance. Sonography has been well studied in the evaluation of retained foreign bodies and has been proved to be both sensitive and specific.

In conclusion, retained bullet in the extremity can migrate distally. The presence of migration should be considered an indication for surgical intervention. Ultrasound examination can readily demonstrate and localize the exact size. Removal under ultrasound guidance is a simple and effective way of removing them with small incisions and under local anesthesia in the emergency department.

Conflict of interest

Sanjay Meena, Amit Singla, Pramod Saini, Samarth Mittal, Buddhadev Chowdhary declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this paper.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). All patients provided (written) informed consent to enrolment in the study and to the inclusion in this article of information that could potentially lead to their identification.

Human and animal studies

The study was conducted in accordance with all institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

References

- 1.Barrett NR. Foreign bodies in the cardiovascular system. Br J Surg. 1950;1950(37):416–445. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003714804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bining HJ, Artho GP, Vuong PD, Evans DC, Powell T. Venous bullet embolism to the right ventricle. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:e296–e298. doi: 10.1259/bjr/64277826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ceylan D, Cosar M. Migration of a bullet in the lumbar intervertebral disc space causing back pain. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2008;48:188–190. doi: 10.2176/nmc.48.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colquhoun IW, Jamieson MP, Pollock JC. Venous bullet embolism: a complication of airgun pellet injuries. Scott Med J. 1991;36:16–17. doi: 10.1177/003693309103600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Maio VJM. Gunshot wounds. 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutiérrez V, Radice F. Late bullet migration into the knee joint. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):E15. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson JA, Powell A, Craig JG, Bouffard JA, van Holsbeeck MT. Wooden foreign bodies in soft tissue: detection at US. Radiology. 1998;206(1):45–48. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.1.9423650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelassi F, Pietrabissa A, Ferrari M, Mosca F, Vargish T, Moosa HH. Bullet emboli to the systemic and venous circulation. Surgery. 1990;107:239–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morton JR, Reul GJ, Arbegast NR, Okies JE, Beall AC., Jr Bullet embolus to the right ventricle. Report of three cases. Am J Surg. 1971;122:584–590. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(71)90303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmelzer V, Mendez-Picon G, Gervin AS. Case report: transthoracic retrograde venous bullet embolization. J Trauma. 1989;29:525–527. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198904000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shannon FL, McCroskey BL, Moore EE, Moore FA. Venous bullet embolism: rationale for mandatory extraction. J Trauma. 1987;27:1118–1122. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198710000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swan KG, Swan RC. Wound ballistics. Gunshot wounds: pathophysiology and management. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1989. pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]