Abstract

Mouth gags are surgical devices placed between the upper and the lower jaw to prevent the mouth from closing during operative procedures of the mouth or throat. Since the beginning of the use of mouth gags in medicine, a wide variety of different models has been invented and described. Till now, slipping, sliding and dislocation in the mouth are problems observed during use, especially of one-sided mouth gags. These problems were already discussed at the beginning of the ninteenth century. The need for introducing a suitable mouth gag is emphasized since then. A modification of the well known one-sided Denhart mouth gag is presented. The new Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag has pivotal pads, which allow to compensate movements in surgery without dislocation. These pivotal pads give a stable and better fixation to the teeth, to the edentulous jaws and enable also to fixate other instruments like tongue plates. The use of the Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag in practice showed a less frequency of sliding and dislocation, especially during manipulation. Besides the description of these modifications a short historic overview of the mouth gag discussion is presented.

Keywords: Mouth gag modifications, Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag, Pivotal pads, Stability, Tongue plate, Denhart mouth gag

Introduction

In german medieval times mouth gags or props were called “Kiefer- or Mundsperre” and were instruments used in torture practice. Besides the fact, that the Christian inquisition is linked with barbarous torture, it was not used principally in every cases. In the beginning of 1220 AD, torture was reintroduced though recommended in Roman law and considered as a legitimately lawful procedure. In torture, especially mouth gags were used to keep the suspects mouth open, leading to dysphagia and jaw pain, inability to speak and swallowing saliva. Additionally, liquids could be instilled causing asphyxia [1].

In later times, mouth gags were used in medical situation to open the patients mouth for examination, insertion of instruments, administration of feeding or dental care. Sometimes this was necessary because of fear, but more frequently due to illness such as tetanus, epilepsy, stroke, hysteria, coma etc. [2]. Since the medical use of mouth gags, a wide variety of different mouth gags, with or without tongue depressors or plates, one- or double-sided, were invented and distributed [2–10].

It was obvious from the early beginning, that a reliable mouth gag was needed to keep the mouth open continuously. Besides the fact that some of the different models also fixate the tongue, other models showed a more or less tendency to slip, slide away and finally to dislocate. Especially disadvantages of single-sided mouth gags are sliding as well as the dislocation within use [3].

Interestingly, in early 1907, Colt already mentioned, that there were enough reasons for bringing forward the subject of a mouth gag designed to suit the needs of the general practitioner, surgeon, dental surgeon and anaesthetist. In those times, he already remarked besides the large number of different gags on the market, that a single perfect gag was missing, which supplies all needs [4].

Therefore, I would like to introduce a new mouth gag on the basis of a Denhart mouth gag, which was modified to have a better fixation in the mouth. The use of this mouth gag in practice showed less frequency of sliding and dislocating, especially during manipulation. This modification will be presented here.

Modification

The new Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag (Fig. 1, distributed by Medicon eG, Tuttlingen, Germany) is based on the Denhart mouth gag, which is a one-sided mouth gag. This mouth gag was chosen as the platform for the changes as described below.

Fig. 1.

Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag with a removable tongue plate mounted to the gag

The Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag was developed in order to optimize the qualities as well as to bypass the disadvantages of the Denhart mouth gag and to improve benefits with its modification in the practice. Because of its basic construction, the Denhart mouth gag allowed this technical changes in a sufficient way. The additionally pads pivotally mounted keep close contact to the patient’s alveolus or teeth during opening and passive manipulation (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the pads could adjust to each surface of the teeth or endentouls alveolus. The cusp of the teeth could also slide into the hole of the pads (Figs. 2b, 3a) and the ends of the pivotal pads get fixed to the interproximal area (Fig. 3b). This adaptation enables more stability. The functions of the pivotal pad allow the gag to be moderately moved during the manipulation of intraoral surgery without sliding or dislocation. This turned out to be a benefit especially in orthognathic surgery.

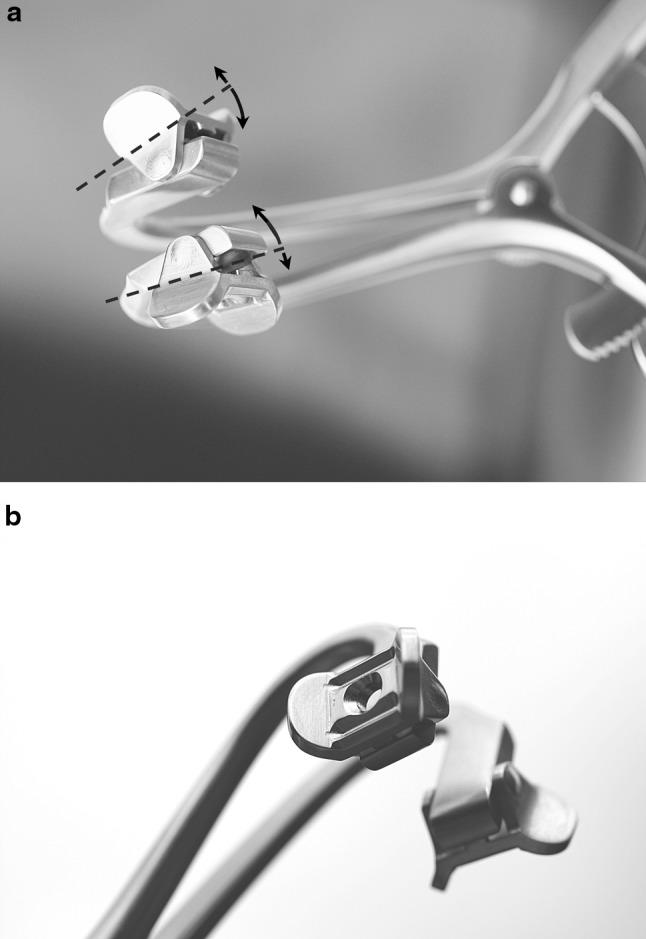

Fig. 2.

a The pivotal mounted pads allow adapting to the surface of the teeth or alveolus of the jaw, b The central hole in the pads let the cusp of the teeth to slide in and to be straight held in slight movements of the jaw or the instrument in use. In result, facile movements can be tolerated without dislocation

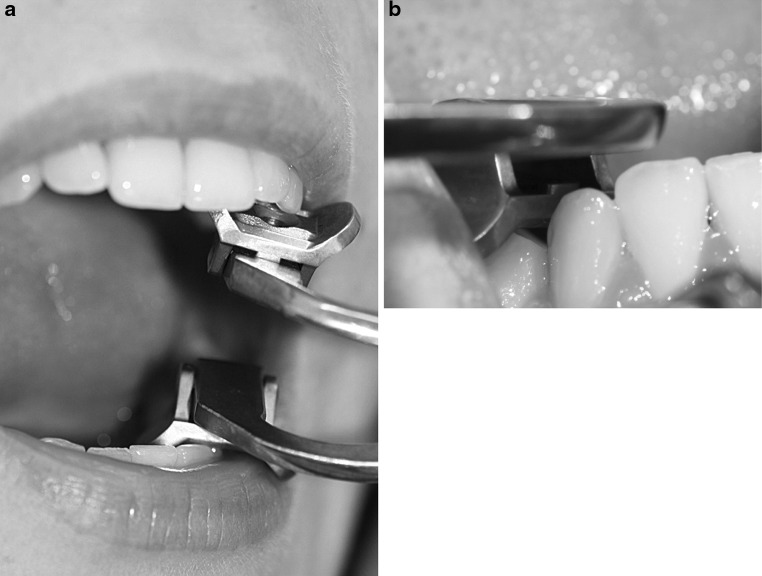

Fig. 3.

a Inserting the gag with placing the hole of the pad to the cusp of the canine, b fixation of the pad to the interproximal area with a stop for additional hold

During clinical and surgical practice, the dislocation and sliding were less frequent observed in contrast to the original Denhart mouth gag. The Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag has been used in a large number of patients and has not encountered any trauma to the mandible or the teeth so far. After introduction in July 2008, the Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag was used in orthognathic surgery in 250 cases. It is regularly used in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis or bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis risk patient surgery in 150 cases, because of its good controlled force application to the gingiva in edentulous jaw. Additionally, it has been used minimally in another 100 cases of other surgical operations.

The observed better stability in the mouth allows additional fixing of instruments, such as a tongue plate to the mouth gag (Fig. 4). It could be observed in use, that the forces by the tongue depressor, as a lever arm, did not dislocate the gag. The tongue depressor was used in 80 cases as well.

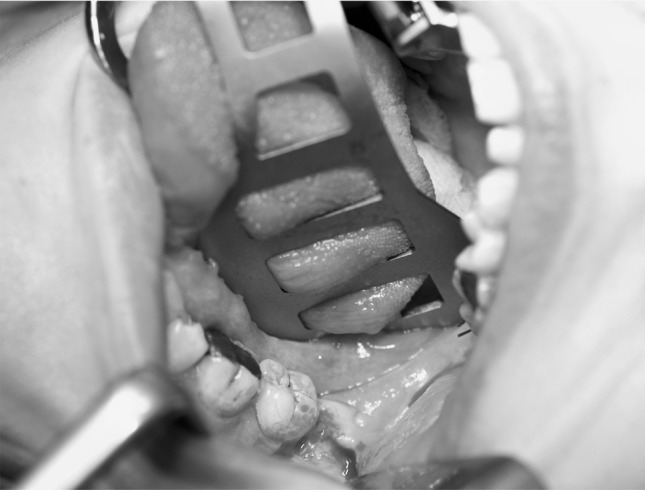

Fig. 4.

The Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag with a fixed tongue plate in situ for a wisdom tooth operation. The tongue plate displayed here has an extended pad for a better retraction of the tongue giving a better overview of the operation field to the surgeon

Discussion

The earliest known medical used mouth gags are dated to the late 1500 AD. Lorenz Heister (1683–1758), a military surgeon, who first described the appendicitis, had also treated many patients with tetanus. He developed a screw-like device to open the patients’ mouth in trismus. This became the classic prototype for most used future models. His mouth gag of excentric pattern, introduced in 1714, was still advertised 250 years later by Mayer and Philips around 1930 and could still be ordered in minor modifications (Table 1) [5]. Principally, the development of general anaesthesia after 1846 resulted in an increased demand for jaw opening devices. Originally, the mouth gag must be able to apply forces to open the mouth. This indeed, is only necessary in limited cases today. In contrast to the Heister gag, most of the mouth gags are, single-sided used, employing an excentric pivot [5].

Table 1.

List of different models of mouth gags mentioned explicit in literature or still available today

| Mouth gag | Side of insertion |

|---|---|

| Buxton | One-sided |

| Buxton–Ackland | One-side |

| Collin | Both-sides with tongue plate |

| Colt | One-sided |

| Davis | One-sided |

| Davis–Boyle (Boyle–Davis) | One-sided with tongue plate |

| Davis–Crowe (Crowe–Davis) | One-sided with tongue plate |

| Denhart (Denhardt) | One-sided |

| Dingman | Both-sides with tongue plate, bilateral side retractors |

| Dott | One-sided with tongue plate |

| Doyen | One-sided |

| Doyen–Collin | One-sided |

| Doyen–Jansen | One-sided |

| Featherstone | One-sided |

| Fergusson | One-sided |

| Fergusson–Ackland | One-sided |

| French | One-sided |

| Geffer | Both-sides with tongue plate |

| Heister | One-sided |

| Jennings | Both-sided with/without tongue plate |

| Kilner | One-sided with tongue plate |

| Kilner–Doughty | One-sided |

| Lane | One-sided |

| Mahu | One-sided with tongue plate |

| Mason | One-sided |

| Mason–Ackland | One-sided |

| McIvor | Both-sides with tongue plate |

| Mickesson mouth prop | One-sided |

| Molt | One-sided |

| Molt–Doyen | One-sided |

| Rose | One-sided |

| Roser–König | One-sided |

| Schmid | One-sided |

| Sklar–Doyen–Jansen (Sklar molt) | One-sided |

| Sluder–Jansen | One-sided |

| Whitehead | Both-sided with/without tongue plate |

Since the early beginning, different mouth gags had been invented. For example, from 1868 until 1886 Mason proposed various gags after numerous failures. Ackland showed 1897 at the meeting of the Odontological Society a slight modification of the Mason’s gag, he had suggested. He placed the jaws side by side instead of one over the other and made the wedge going between the teeth much narrower [4]. Snow explained changes to the Fergusson’s gag to handle edentulous patients much easier [6]. In 1902, Colt analysed the defect in previous mouth gags in order to achieve a scientifically designed instrument, after statistical analysis of measurements made on 500 patients [4, 5]. He added anaesthetic tubes to the jaws and pointed out that the Coleman’s dental gag of 1861 was the origin of one-sided mouth gags [4]. All these mouth openers are characterised by plain handles to accommodate the power of hand pressure [4]. Cotterill [7] mentioned, that a single gag gives more space for a surgeon than a double one. Interestingly, already in 1886 a modification of the Mason gag was described, allowing the gag to move slightly to compensate movements. Besides the initial purposes to avoid straight forces to the teeth and not to break or displace them [8], it demonstrates already the idea of needing mobility for a better fixation and stability.

Until now, mouth gags have been widely used in surgery. A variety of different mouth gags is described and distributed today (Table 1) [2–5, 9]. Already Colt mentioned in 1907, that the number of gags in the market was large, but the number of those, which combine in one instrument all the essentials, is rare [4]. Many years later, on a Caribbean work trip, Dingman considered his mouth gag as “happiness” for a surgeon operating on cleft palate, but Millard stated in his book in 1976, that he experienced a couple of difficulties with that gag, mostly with its adaptability to fit to irregular alveolae [9].

One of the main problems of every one-sided mouth gag is a dislocation during surgery. Liehn and Nehse [3] especially described those instruments, which do not have edges at the plain pads, to slip and slide away. In 1921, Black [10] described changes of the pad to avoid slipping forward and outward during opening the mouth. Furthermore, moving the jaw may lead to a dislocation with the need to reinsert the gag, always meaning an incident. In contrast to single-sided mouth gags, the notorious problems of double-sided mouth gags are the size and difficulty in positioning [3].

In 1897, Snow [6] emphasized, that slipping of mouth gags may embarrass the operator and often seriously deteriorating his results. Therefore, this might present difficulties during surgery and may lead to an interruption of the operation process.

The Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag demonstrated a better fixation and stability due to its pivotal pads. It also contributes to consolidate additional instruments such as a tongue plate. It has been used in a large number of patients and has not encountered any trauma to the mandible or the teeth nor has been any dental damage reported so far. This is in contrast to the opinion of some surgeons, who do not accept a direct metal to tooth contact. On the other side, a soft plastic coverage of teeth props are in danger of being damaged and getting lost during operation procedures. Finding this debris in the wound turned out to be always difficult.

The new Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag with its modifications can be well recommended for a more stable Enoral placement. The stable and fixed position contributes a straight and undisturbed work flow during the surgical procedure. The possibility to fix additional instruments, like a tongue depressor, affords more efficiency.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Medicon eG, Tuttlingen, Germany for their support developing the Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Sebastian Hoefert is receiving financial grants for giving his licensing rights of the Denhart–Hoefert mouth gag to Medicon eG, Tuttlingen, Germany.

References

- 1.Bühler A, Dirlmeier U, Ehrhardt H, Fuhrmann B, Hartmann W, Hösch Kaufmann UR, Singer HR (2004) Das Mittelalter, 1st edn. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 254–261

- 2.Kravetz RE. Mouth gag. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liehn M, Nehse G. Mund-Kiefer-Gesichtschirurgie. In: Liehn M, Steinmüller L, Döhler R, editors. OP-Handbuch: Grundlagen, Instrumentarium, OP-Ablauf. 4. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2007. pp. 520–531. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colt GH. The gag. Lancet. 1907;170:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)30516-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirkup JR. The history and evolution of surgical instruments: XI retractor, dilators and related inset pivoting instruments. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84:149–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snow H. The “mammoth-tusk” gag for senile and edentulous jaws. Lancet. 1897;149:387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)95584-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotterill MJ. Gag, cheek retractor, and tongue depressor. Lancet. 1888;132:1074. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)27524-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mason F. Mason’s gag. Lancet. 1886;127:260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)06579-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millard DR (1976) Anesthesia in cleft (gus, tubes and gags). In: Millard DR (ed) Cleft craft, 1st edn. Little Brown and Company, Boston, pp 145–158

- 10.Black K. An improved mouth-gag. Lancet. 1921;197:82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)22368-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]