Abstract

Odontomas are the most common benign tumours of odontogenic origin. Due to their hamartomatous nature, they are usually asymptomatic but can cause impaction of one or more teeth. They consist microscopically of all the tissue types found in a developed tooth. We present a case of a large sequestrating complex odontoma resulting in facial asymmetry, cellulitis, pain and partial loss of function. This case has significance, as odontomas of this large size have rarely been reported.

Keywords: Complex odontoma, Radiographic features, Odontogenic, Hamartoma, Sequestration

Introduction

The odontoma is a benign odontogenic tumor combining mesenchymal and epithelial dental elements. Paul Brocka first described it in 1866 [1]. The WHO classification on odontogenic tumours defines it as a malformation in which all dental tissues are represented, individual tissues being mainly well formed but occurring in a more or less disorderly pattern, and are classified as compound or complex odontomas [2]. They are therefore composed of the different dental tissues, namely enamel, dentine, cementum and, in some cases, pulp tissue [3].

The complex odontoma is less frequently seen than the compound odontoma. The sequestrating odontoma is one that perforates through the mucosa into the oral cavity. In literature these sequestrating odontomas are referred to as erupting odontomas and are considered to be rare [4]. Till date, only 20 cases of the erupting type have been reported in the Scientific literature [5]. Of these, nine were found to be compound odontomas while the remaining 11 were complex odontomas.

The etiology of odontomas is largely unknown but has been attributed to various pathological conditions such as local trauma, inflammation, infectious processes, growth pressure [6], hereditary anomalies (Gardner’s syndrome, Hermann’s syndrome), odontoblastic hyperactivity and alterations in the genetic component responsible for controlling dental development. The persistence of a portion of the dental lamina may be an important factor in the etiology of an odontoma, which occurs instead of a tooth [7].

Compound odontomas are pre-dominantly seen in the anterior maxilla whereas complex odontomas are typically seen in the posterior maxilla or mandible [8]. Compound odontomas and most complex odontomas are relatively small and seldom exceed the size of a tooth in the areas where they are located. Hence, most of them are asymptomatic and are detected on routine panoramic radiographs [9]. Large odontomas, however, measuring up to 6 cm or more in size and causing expansion of the jaws, have been reported in the literature [10]. The largest odontoma found in a human weighed 0.3 kg [11].

Radiographically, odontomas present as radiopacities of similar density to the tooth structure usually surrounded by a narrow radiolucent rim. Compound odontomas appear as clusters of tooth-like structures of varying sizes and volumes that occur between the roots of erupted teeth. They may resemble miniature teeth, sometimes referred to as denticles. Seldom do these prevent tooth eruption [10]. Complex odontomas however present as irregular and disorganized radiopaque masses [12]. They are frequently responsible for the prevention of tooth eruption. A complex odontoma may be radiographically confused with an osteoma or some other highly calcified bone lesion [10].

This study presents a review of the literature and describes a patient with a complex odontoma in the process of sequestration into the oral cavity.

Case Presentation

A 24-year old female presented to the department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, Medunsa Oral Health Centre, University of Limpopo, South Africa, in August 2008 with a painful swelling for past 1 week duration on the right side of the mandible and mild trismus. The patient was otherwise healthy with no significant medical history. Extra-oral examination revealed a diffuse right-sided submandibular swelling and cellulitis with a purulent discharge at the lower border of the mandible in the insertion of masseter muscle (Fig. 1). Intra-oral examination revealed the 47 and 48 to be missing. Patient gave a history of extraction of 47 and 48 due pain before few years. The right posterior quadrant of the mandible was expanded bucco-lingually. The mucosa distal to the 46 and up to the retro-molar area was breached by a large yellowish-brown hard mass, which resembled dentine (Fig. 2). Due to the severity of the infection, the patient was admitted. Empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy was commenced. The regimen was selected from that available at the local hospital. Dual therapy to cover infections caused by staphylococcus and streptococcus organisms was selected (intravenous administration of 500 mg Ampicillin, and 500 mg Flucloxacillin) six hourly for 72 h.

Fig. 1.

Swelling with draining sinus and sub-mandibular cellulitis at the lower right mandibular border

Fig. 2.

Intraoral view of the lesion

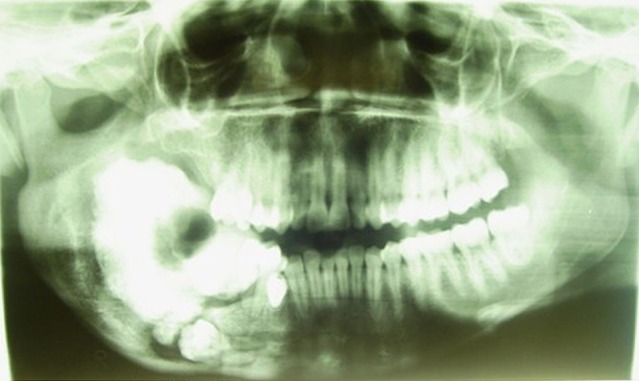

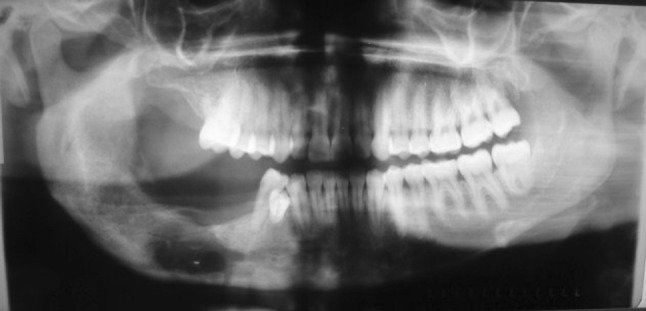

The panoramic radiographours revealed a large irregular radiopaque mass extending anteriorly from the 46 to just below the sigmoid notch posteriorly, inferiorly to just above the lower border of the mandible and superiorly to beyond the alveolar crest. The lesion was surrounded by a distinct radiolucent rim. An impacted molar tooth was located just above the lower border in line with the 46 region (Fig. 3). Further history taking revealed that this patient had previously attended our department in 2004 for the same complaint, but subsequently defaulted. She was lost to follow up until her return in 2008. The panoramic radiograph taken in 2004 showed a large radiopacity extending from the distal aspect of the 46 to the mid-ramus posteriorly and the lower border of the mandible inferiorly. There was an impacted molar at the lower border of the mandible. The lesion was surrounded by a radiolucent border, which seemed to be more pronounced in the ramus (Fig. 4). A comparison of the panoramic radiograph taken in 2004 and 2008 clearly illustrates the changes in the lesion over a 4 year period as it sequestrated into the oral cavity. In 2004 the lesion appeared to be less dense, smaller and positioned below the occlusal plane. The radiolucent rim was also narrowed. In 2008 the lesion appeared to have grown in size. It was more dense, probably an indication of its advanced stage of maturity. It had also moved to beyond the occlusal plane. The radiolucent rim was wider, and the impacted tooth seemed to have moved occlusally with an enlarged follicle surrounding its crown. The inferior alveolar canal was displaced inferiorly towards the lower border of the mandible. The radiographs of 2004 and 2008 did not show root resorption.

Fig. 3.

Pre-operative panoramic radiograph 2008; the lesion has grown since 2004 and shows clearly a well-defined radiolucent rim which is the result of overlying infection

Fig. 4.

Panoramic radiograph (2004); the extension of the radiopaque lesion into the ramus and the impacted first molar above the inferior border of the mandible is clearly visible. The lesion is surrounded by a radiolucent border, which seems to be more pronounced in the area of the ramus

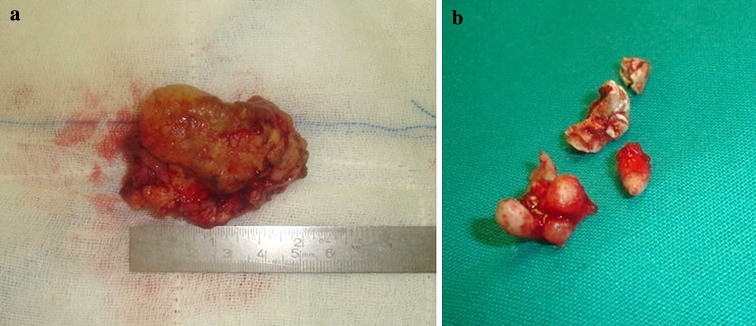

The lesion was treated by surgical enucleation under general anaesthesia by an intraoral approach. The mass measured approximately 5.5 × 4 × 2.5 cm (Fig. 5a). The impacted molar was removed at the same time as the lesion. This was done carefully to avoid a pathological fracture of the mandible and damage to the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle. A comparison of the radiographs taken in 2004 and 2008 and the anatomy of the surgically removed impacted molar suggested this tooth to be a right mandibular lower third molar (Fig. 5b). Due to the buccal and lingual expansion of the mandible caused by the lesion and the resultant inadequate tissue coverage the bone cavity was packed with bismuth iodine paraffin paste soaked in ribbon gauze (BIPP). The BIPP was removed incrementally over a 3-week period (Fig. 6). The patient made a follow up visit after 3 months. At this visit intraoral photographs revealed healing of the defect by secondary intention (Fig. 7). After removal of the impacted molar, rigid plate fixation of the thinned lower border was not done due to the presence of sepsis. The surgery was contradicted performed during the 72 h high dose intravenous antibiotic regimen, which was continued 1 day post-operatively. The patient was placed on antibiotics, analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents for a further 7 days at discharge. Her post-operative recovery was uneventful and progressive closure of the cavity was observed over the following 3 months. The patient was again lost to follow up after six months. Histopathology confirmed the lesion to be a complex odontoma (Fig. 8). The soft tissue component of the odontoma was necrotic with the presence of an acute inflammatory infiltrate.

Fig. 5.

a Specimen sample of lesion. b Fractured impacted tooth after removal

Fig. 6.

Panoramic radiograph after removal of BIPP

Fig. 7.

Intra-oral view 3 months later—note the healing by secondary intention

Fig. 8.

Micrograph shows a haphazard mixture of odontogenic hard tissue. Extensive necrosis and inflammation was present. (Histopathology, courtesy: Prof E. J. Raubenheimer)

Discussion

Odontomas are benign odontogenic tumours composed of enamel, dentine, cementum and pulp tissue, wherein both epithelial and mesenchymal cells co-differentiate simultaneously [13–15]. The odontoma is thought to arise from remnants of the dental lamina, the cell rests of Serres, they are the most commonly responsible for odontogenic tumours. The lesions are slow growing and non-aggressive in behavior and are regarded by some authors as hamartomatous malformations which lack the diagnostic features of persistent and uncoordinated growth that characterize tumours and hence have a limited growth potential [16]. Odontomas are usually clinically asymptomatic, but are often associated with disturbances in tooth eruption [17]. In most cases they are detected as incidental findings on routine radiographs [18]. In exceptional cases they may perforate the alveolar crest and become exposed to the oral cavity with resultant pain, swelling and bony expansion [19]. Pathologic changes such as impaction, malpositioning, aplasia, malformation and devitalization of adjacent teeth are associated with 70% of odontomas. [20–22].

The mechanism of odontoma eruption appears to be different from tooth eruption because of their lack of periodontal ligament. Therefore, the force required to move the odontoma is not linked to the contractility of fibroblasts, it is the same case for teeth. Although there is no root formation in odontoma, its increasing size may lead to resorption of the overlying bone and hence exposure to the oral cavity. The increase in size of the odontoma over time produces a force sufficient to cause bone resorption [23, 24].

The process of exposure to the oral cavity is based on persistent growth of the lesion.

In our case study we present a mature complex odontoma demonstrating radiographic changes over a 4-year period. This lesion should be differentiated from a sequestrating osteoma, familial gigantiform cementoma, ossifying fibroma, a focal chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis or a sequestrum associated with chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis. Osteomas appear as well defined radiopaque masses on radiographs. Periosteal osteomas may show a uniform radiopaque pattern or may demonstrate an internal trabecular structure [25]. Smaller endosteal osteomas are difficult or impossible to differentiate from sclerotic bone, which may represent a chronic inflammatory process. Their true nature can be confirmed only by documented continued growth [10]. Radiographically the familial gigantiform cementoma (FGC) shows a lobulated calcified mass, which can reach large dimensions [26]. The radiographic differences between a FGC and a large odontoma are subtle and microscopic examination is required to distinguish the two lesions. Large ossifying fibromas may result in painless swelling of the involved bone with facial asymmetry. Mature ossifying fibromas may show a radiolucent rim that is rarely as wide as in odontomas and gigantiform cementomas [27]. Focal sclerosing osteomyelitis manifests as increased bone density around a focus of persistent inflammation usually associated with one or more non-vital teeth. These radio-densities are poorly defined and smaller in size without a radiolucent rim. A regional lymphadenitis and a draining sinus may accompany some cases [28]. In our case the odontoma had sequestrated into the oral cavity probably associated with previous extractions of teeth. Sequestrum formation is associated with chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis. A sequestrum however, does not have a radiolucent rim like an odontoma.

This case is unusual because it is the first case to be reported that demonstrates the distinct radiographic changes over a period of 4 years, apparent movement of the impacted tooth occlusally, sequestration of the odontoma and the presence of cellulitis with an extra oral sinus.

Conclusion

Complex odontomas are benign hamartomatous proliferations, which are considered not to increase in size after calcification of the odontogenic tissues. Our case shows that they can increase in size, which can give rise to complications, especially in the presence of infection [25]. Surgical removal of large complex odontomas is the treatment of choice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor E. J. Raubenheimer Head of Department Oral Pathology at the School of Oral Health Sciences, Medunsa Campus, University of Limpopo, South Africa, for providing us with the histopathology slides and report. We also thank Dr. M. Meyer, former Registrar of the Department of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, Faculty of Oral Health Sciences, Medunsa Campus, University of Limpopo, South Africa, for his editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Cildir SK, Sencift K, Olgac V, Sandalli N (2005) Delayed eruption of a mandibular primary cuspid associated with compound odontoma. J Contemp Dent Pract 15;6(4):152–159 [PubMed]

- 2.Kramer IRH, Pindborg JJ, Shear M. Histological typing of odontogenic tumours. World Health Organization. International histological classification of tumours. 2. Berlin: Springer; 1992. pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noffke CEE, Chabikuli NJ, Nzima N (2005) Impaired tooth eruption: a review. SADJ 60(10):422, 424–425 [PubMed]

- 4.Ragalli CC, Ferreira JL, Blasco F. Large erupting complex odontoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;29(5):373–374. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(00)80056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serra-Serra G, Berini-Aytes L, Gay-Escoda C. Erupted odontomas: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14(6):E299–E303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabov T, Mkrmpotic J, Grgurevic B, Peric B, Jokic D, Manojlovic S. Large complex odontoma of left maxillary sinus. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005;117(21–22):780–783. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0462-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shekar SE, Rao RS, Gunasheela B, Supriya N. Erupted compound odontoma—case report. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2009;13(1):47–50. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.48758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milero M, Ghali GF, Larsen PE, Waite PD. Peterson’s principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery. Maxillofacial pathology. 2. Hamilton, London: BC Decker; 2004. p. 590. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philipsen HI, Reichart PA, Praetorius F. Mixed odontogenic tumours and odontomas. Considerations on interrelationship. Review of the literature and presentation of 134 new cases of odontomas. Oral Oncol. 1997;33(2):86–99. doi: 10.1016/S0964-1955(96)00067-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JF (2002) Odontogenic cysts and tumours. In: Oral and maxillofacial pathology, 2nd edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia (PA), pp 589–637

- 11.Wood NK, Goaz PW, Lehnert J. Mixed radiolucent-radiopaque lesions associated with teeth. In: Wood NK, Goaz PW, editors. Differential diagnosis of oral and maxillofacial lesions. Singapore: Harcourt Brace and company Asia Pte Ltd; 1998. pp. 289–314. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slootweg PJ. Odontogenic tumours—an update. Curr Diagn Pathol. 2006;12:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cdip.2005.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olgac V, Koseogli BG, Aksakalli N. Odontogenic tumours in Istanbul: 527 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44(5):386–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajike SO, Adekeye EO. Multiple odontomas in the facial bones. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;29(6):443–444. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(00)80077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dagistan S, Goregan M, Miloglu O. Compound odontoma associated with maxillary impacted permanent central incisor tooth. In: The Internet J D Sc. ISSN: 1937-8238. pp 1–7

- 16.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. An odontogenic gingival epithelial hamartoma (OGEH) possibily derived from remnants of the dental lamina (“dental laminoma”) Oral Oncol. 2004;40:63–67. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(03)00136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fregnani ER, Fillipi RZ, Oliveira CR, Vargas PA, Almeida OP. Odontomas and ameloblastomas: variable prevalences around the world. Oral Oncol. 2002;38(8):807–808. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(02)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sriram G, Shetty RP. Odontogenic tumours: a study of 250 cases in an Indian teaching hospital. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:e14–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amailuk P, Grubor D. Erupted compound odontoma: case report of a 15-year-old Sudanese boy with a history of traditional dental mutilation. Dent J. 2008;204(1):11–14. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneko M, Fukuda M, Sano T, Ohnishi T, Hosokawa Y. Microradiographic and microscopic investigation of a rare case of complex odontoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86(1):131–134. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theodorou SJ, Theodorou DJ, Sartoris DJ. Imaging characteristics of neoplasms and other lesions of the jawbones Part 1. Odontogenic tumours and tumourlike lesions. Clin Imaging. 2007;31(2):114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashkenazi M, Greenberg BP, Chodik G, Rakocz M. Postoperative prognosis of unerupted teeth after removal of supernumerary teeth or odontomas. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131(5):614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vengal M, Arora H, Ghosh S, Pai KM. Large erupting complex odontoma: a case report. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73(2):169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasudevan V, Manjunath V, Bavle RM. Large erupted complex odontoma. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2009;21:92–97. [Google Scholar]

- 25.White SK, Pharoah MJ. Benign tumours of the jaw. In: White SK, Pharoah MJ, editors. Oral radiology principles and interpretation. Los Angeles: Mosby; 2003. pp. 426–444. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdelsayed RA, Eversole LR, Singh BS, Scarbrough FE. Gigantiform cementoma: clinicopathologic presentation of 3 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91(4):438–444. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.113108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JF (2002) Bone Pathology. In: Oral and maxillofacial pathology, 2nd edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia (PA), pp 533–587

- 28.Wood NK, Goaz PW. Bony lesions. In: Wood NK, Goaz PW, editors. Differential diagnosis of oral and maxillofacial lesions. St Louis: Mosby; 1997. pp. 486–487. [Google Scholar]