Abstract

We present evidence that chordate protamines have evolved from histone H1. During the final stages of spermatogenesis, the compaction of DNA in many organisms is accomplished by the replacement of histones with a class of arginine-rich proteins called protamines. In other organisms, however, condensation of sperm DNA can occur with comparable efficiency in the presence of somatic-type histones or, alternatively, an intermediate class of proteins called protamine-like proteins. The idea that the highly specialized sperm chromosomal proteins (protamines) and somatic chromosomal proteins (histones) could be related dates back almost to the discovery of these proteins. Although this notion has frequently been revisited since that time, there has been a complete lack of supporting experimental evidence. Here we show that the emergence of protamines in chordates occurred very quickly, as a result of the conversion of a lysine-rich histone H1 to an arginine-rich protamine. We have characterized the sperm nuclear basic proteins of the tunicate Styela montereyensis, which we show consists of both a protamine and a sperm-specific histone H1 with a protamine tail. Comparison of the genes encoding these proteins to that of a sister protochordate, Ciona intestinalis, has indicated this rapid and dramatic change is most likely the result of frameshift mutations in the tail of the sperm-specific histone H1. By establishing an evolutionary link between the chromatin-condensing histone H1s of somatic tissues and the chromatin-condensing proteins of the sperm, these results provide unequivocal support to the notion that vertebrate protamines evolved from histones.

The canonical structure of histone H1 consists of a tripartite organization, with a globular core containing a conserved winged helix motif, flanked by less well conserved lysine-rich N- and C-terminal tails. Somatic histone H1s typically contain little or no arginine. In contrast, protamines are relatively small (4,000–12,000 Da), are composed of >50% arginine, and contain little or no lysine (1). From the time that these nuclear proteins were first characterized, it was suggested that histones of somatic cells and protamines of germ cells were evolutionarily related (2, 3). It was hypothesized in 1973 (4), based on compositional amino acid analysis, that protamines had evolved from a primitive somatic-like histone precursor via a protamine-like (PL) intermediate through a mechanism of vertical evolution. This is supported by the observation that organisms that replace histones with protamines in the mature sperm are always found at the furthermost tips of the evolutionary branches (5), whereas organisms that retain sperm-specific germinal histones are found in the sperm of more primitive organisms such as the sponge Neofibularia (6) and the sea urchin (7).

Histone H1-like sperm nuclear proteins have been identified in a diverse range of organisms, including marine invertebrates (8), amphibians (9, 10), and fish (11, 12). In comparison to their somatic counterparts, histone H1s that mediate sperm-specific chromatin compaction contain elevated amounts of the charged amino acids lysine and arginine. Although the C-terminal tails of somatic H1s are composed of 30–40% lysine and no arginine, the C-terminal tail of the sperm-specific histone H1 of sea urchin (13) contains 44.3% lysine and 8.4% arginine (Arg + Lys = 52.7%). The mechanism responsible for this increase in both lysine and arginine content is most certainly an accumulation of point mutations, driven by the selective advantage conferred by the increased efficiency of highly basic molecules to screen the charge of DNA and thus achieve a more compact chromatin structure. The relatively quick specialization of histone H1 for sperm chromatin compaction is not unexpected, because sperm nuclear basic proteins (SNBPs), like many of the reproductive proteins, are among the most rapidly evolving proteins in the animal kingdom (14, 15).

It has been suggested that protamines did not arise from an ancient eukaryotic protein but instead have a retroviral origin (16). The hypothesis of retroviral horizontal transmission was proposed to account for the apparently random distribution of protamines in fish and was based on the observation that the flanking regions of the protamine genes from rainbow trout exhibit a large degree of similarity to the long terminal repeats of avian retroviruses (16). However, a detailed systematic analysis of the distribution of SNBPs in fish provided additional support for the vertical evolution hypothesis by revealing that the sporadic distribution of protamines was not random and could be traced phylogenetically (17). The principal difficulty with the theory of vertical evolution of protamines, however, was the absence of a mechanism by which a mainly lysine-rich histone H1 could be converted to an extremely arginine-rich protamine.

To address this difficulty, we have examined the SNBPs of the primitive chordates Styela montereyensis and Styela plicata, revealing that each possesses both an arginine-rich protamine and a histone H1 with an extremely arginine-rich protamine tail. Another tunicate, Ciona intestinalis, was found to possess a single major SNBP, a lysine-rich sperm-specific histone H1. The surprising result of a sequence comparison of the genes encoding these proteins has indicated that this wholesale compositional change is the result not of a gene fusion event (retroviral or otherwise) but rather of a frameshift mutation in the tail of the sperm-specific histone H1. This observation provides direct evidence for an evolutionary mechanism linking the histones of somatic tissues with protamines.

Materials and Methods

Protein Extraction and Sequencing. Chromosomal sperm proteins were extracted and isolated as described (18). Buffers used during the isolation of proteins contained Complete protease inhibitor mixture tablets (Boehringer). The dried pellets were stored at –80°C. Protein sequencing was performed on an ABI Model 473 gas-phase protein sequenator at the Protein Microchemistry Center of the University of Victoria, British Columbia, as described (18).

Gel Electrophoresis. Acetic acid (5%)/urea (2.5 M)/polyacrylamide gels were prepared as described in ref. 18.

Degenerate PCR and RACE. Degenerate primers for PCR were created based on the amino acid sequence of the P1 protein from S. plicata, with the sequences TAYAAYGTHATGGTHAARMG (5′ primer) and TTRTTYTTRTADATRAANCCNCC (3′ primer). PCR was performed on genomic DNA from S. montereyensis by using the PCRSprint thermal cycler (Hybaid, Teddington, Middlesex, U.K.). A touchdown profile was used for the amplification, with an annealing temperature range of 65–45°C over 20 cycles, followed by 10 cycles at 45°C. RACE was performed by using the Marathon cDNA amplification kit (Clontech), with primers based on the genomic fragment obtained from degenerate PCR. The primers were CCTTCGAATACGACCTACTATAGGGCG (5′ primer) and GCGGCCTCTTCGCTATTACGCCAGC (3′ primer).

Results

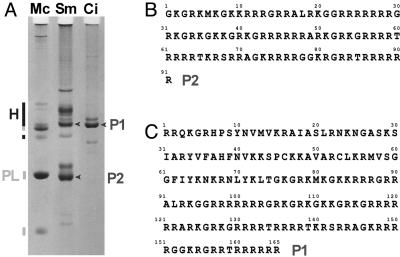

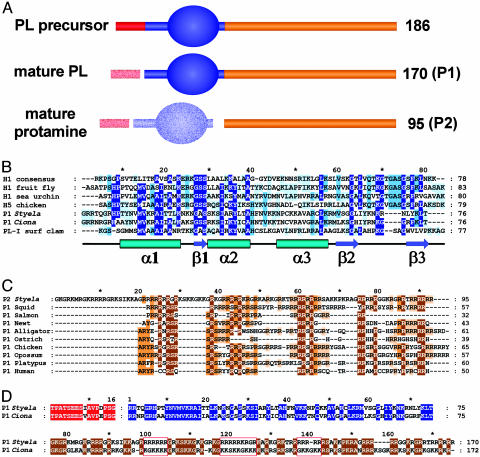

The sperm of the ascidians, S. montereyensis and S. plicata, contains two major nuclear basic proteins (Fig. 1A) (19). These proteins coexist in the mature sperm with 20–25% of a full somatic-type histone complement. Early in this project, we were interested in obtaining the primary amino acid sequence of the SNBPs of S. plicata. Protein microsequencing of the smaller of the two proteins established its identity as a protamine of 91 aa (Styela P2) (Fig. 1B). Containing 51.6% arginine residues arranged in tracts of four to eight residues each, the Styela protamine also displays an unusually high lysine content (20.4%) in comparison with other protamines. Unlike the human protamines P1 and P2, it does not contain cysteine or histidine, respectively (1). Protein microsequencing proved to be extremely difficult and time-consuming for the second major SNBP (Styela P1), a PL protein that is a much larger 165 aa and consists of two distinct domains (Fig. 1C). The leading 78 residues of S. plicata P1 show a remarkable similarity to the N-terminal tail and globular region of histone H1 (Fig. 3B) and to the sperm-specific H1s and PL H1 proteins of other invertebrates (20, 21). The C-terminal tail, surprisingly, is comprised of a 91-aa sequence (amino acids 75–165) identical to that of the protamine (P2) (Fig. 2B). This protein therefore represents a previously undescribed direct evolutionary link between histone H1 and protamines.

Fig. 1.

(A) Acetic acid (5%)/urea (2.5 M)/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of sperm nuclear proteins extracted from testes from Mytilus californianus (Mc), California mussel, used as a protein marker. Mytilus PL proteins are indicated by the orange bars. Sm, S. montereyensis; Ci, C. intestinalis. Somatic-type histones are indicated by bars; sperm nuclear proteins referred to in the text are indicated by arrows. (B) Amino acid microsequencing results for the S. plicata P2 protein. (C) Amino acid microsequencing results for the S. plicata P1 protein.

Fig. 3.

(A) Diagram of sperm protein structure in Tunicates. Leading sequence is red, winged helix region is blue, and C-terminal tail is orange. Numbers indicate protein length in amino acids; mature protein designations are in brackets. Structural features were determined by Chiva et al. (31). (B) Multiple alignment of S. montereyensis P1 N-terminal winged helix region with other winged helix-containing proteins, with secondary structure highlighted below. Secondary structure was inferred from the crystal structure of the globular winged helix of histone H5 (32). The GenBank accession nos., if available, are: H1 consensus (33); H1, fruit fly (P02255); H1, urchin (P15869); H5, chicken (P02259); P1, Styela (AY332242); P1, Ciona (BP019154); and PL-I, surf clam (J.D.L., R. McParland, and J.A., unpublished work). (C) Multiple alignment of S. montereyensis P2 with protamines. The GenBank accession nos., if available, are: P1, squid (AY269798); P1, salmon (X07511); P1, newt (D85426); P1, alligator (Y.S., J.D.L., and J.A., unpublished work); P1, ostrich (34); P1, chicken (M28100); P1, opossum (X74044); P1, platypus (Z26849); and P1/P2, human (Z46940). (D) Alignment of S. montereyensis P1 with C. intestinalis P1. Red open boxes indicate areas containing polyarginine and polylysine tracts, respectively. Amino acids in red, blue, and orange are as in A.

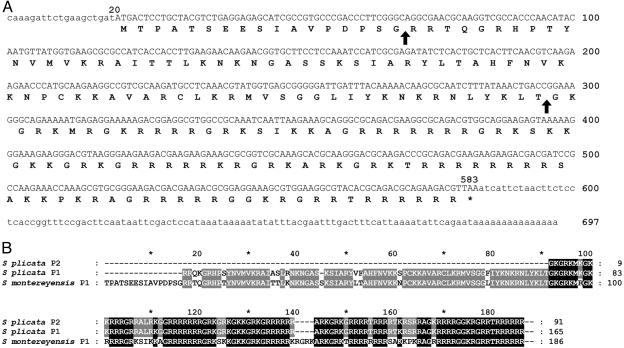

Fig. 2.

(A) Full-length nucleotide sequence of the S. montereyensis P1 cDNA, GenBank accession no. AY332242. Sites of likely posttranslational cleavage are indicated by arrows. (B) Multiple protein alignment of the P1 and P2 SNBPs of S. plicata determined by protein microsequencing compared to the P1 of S. montereyensis determined from the cDNA sequence in A. The P1 proteins exhibit an 89% similarity.

Using degenerate primers based on the amino acid sequence from S. plicata, a genomic fragment of the larger sperm nuclear protein (P1) was obtained from the very closely related S. montereyensis (Fig. 1 A). This partial sequence was then used to design PCR primers for RACE to obtain the full-length cDNA of the P1 from S. montereyensis (Fig. 2 A). The sequence thus obtained codes additionally for a 16-aa leading peptide not present in the mature PL protein (Fig. 2B). Many protamines are processed posttranslationally, including the human P1 and squid P1 (1). Overall, the S. plicata and S. montereyensis P1 proteins are 89% similar, which, considering that these proteins have such a rapid rate of evolution (14, 15), is extremely significant. Henceforth we will refer to the P1 and P2 proteins of S. montereyensis as Styela P1 and Styela P2.

The draft genomic sequence of the Tunicate C. intestinalis had recently been made available, so we proceeded to extract and examine its SNBPs. This revealed a single protein species similar in mobility to the larger of the Styela SNBPs (Fig. 1 A). We then scanned the C. intestinalis genome database by using both our S. montereyensis cDNA sequence and our Styela protein sequences. In addition to two hits that represent somatic histone H1s in Ciona, an H1-like protein with significant similarity to that of the Styela P1 was identified. Like the Styela P1 (and unlike histone H1), it possesses a leading sequence virtually identical and presumably cleaved posttranslationally. As mentioned above, C. intestinalis expresses a single SNBP with a molecular mass corresponding to that predicted by the putative P1 obtained from the sequence database (Fig. 1 A).

At the primary structural level, the putative Ciona P1 protein exhibits a 75% conservation and 53% identity to the P1 from Styela over the entire sequence, but it is clear that the similarity is not uniform (Fig. 3D). Although the N-terminal region of 91 aa exhibits 64% identity, the C-terminal tail is only 41% identical and shows a striking but simple sequence divergence from the Styela P1. Where the Styela P1 tail is composed of >50% arginine and 20% lysine, the Ciona P1 tail contains only 25.3% arginine and almost 50% lysine. Side-by-side analysis of the two proteins shows that in regions where Styela possesses polyarginine tracts, the Ciona P1 has polylysine tracts (Fig. 3D).

Discussion

The ascidian tunicates C. intestinalis, S. plicata, and S. montereyensis are nonvertebrate chordates that diverged very early from other chordates, including vertebrates. There has been a recent surge in scientific interest in ascidians and other urochordates, because their study is helping to illuminate how chordates originated and how vertebrate developmental innovations evolved. According to the most current view of tunicate evolution, Ciona and Styela belong to different orders (Phlebobranchiata and Stolidobranchiata) within the class Ascidiacea (Fig. 4A) (22). It is reasonable to assume that, whereas Styela and Ciona are closely related, a certain amount of evolution has occurred since their divergence from a common ancestor. With respect to their SNBPs, all members of Ascidiacea studied to date, with the exception of the genera Styela, express only a P1 protein (and not P2) in their sperm nuclei (23). Although this observation bears no weight on the issue of lysine and arginine content, it indicates that the posttranslational cleavage of a sperm-specific H1 precursor to a mature protamine is a very recent adaptation for Styela.

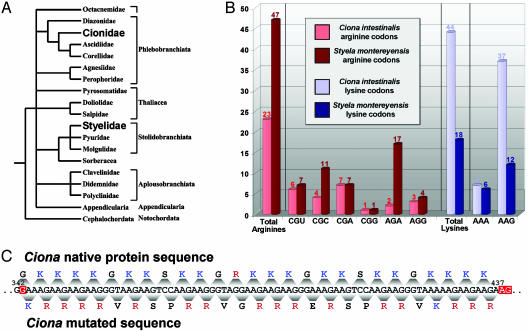

Fig. 4.

(A) Evolutionary tree showing the relationship among members of the tunicates, class Ascidiacea, adapted from Stach and Turbeville (22). (B) Codon frequencies of arginine and lysine codons contained within Styela P2 and the C-terminal 93 amino acids of Ciona P1. (C) Deletion of nucleotide 342 results in a frameshift mutation that converts 15 lysine codons to arginine codons.

How is it possible that two homologous proteins from such closely related organisms could manifest such a wholesale switch in amino acid composition? Analysis of the codon usage in the C-terminal tails of the Ciona and Styela PLs (Fig. 4B) shows significant codon bias in each. Comparison of the lysine codon usage reveals that, although each utilizes a nearly equivalent number of AAA codons to encode lysine, 25 of the 26 lysines (96%) that the Ciona PL possesses over the Styela PL are AAG codons. Of the six possible codons that encode arginine, 15 of the 24 additional arginines (63%) possessed by the Styela P1 are AGA codons. Except for the gain of seven CGC codons, the remaining arginine codons remain essentially constant. Although the lysine codon bias of the Ciona P1 is marked (84% AAG), a preference for AAG over AAA lysine codons is a typical feature of histone H1. For example, the human H1a gene encodes lysine with 78.5% AAG codons, and the sea urchin H1 utilizes 76% AAG lysine codons. A particularly extreme example is the histone H1 gene of Leishmania panamensis, which utilizes AAG codons to encode lysine in every position. It is reasonable to presume, therefore, that whereas C. intestinalis is not a direct ancestor of S. montereyensis, its sperm-specific histone H1 is most likely very representative of a common ancestor to both organisms. The functional basis for this lysine codon bias is most likely related to the maintenance of DNA stability in lysine-rich coding regions.

The conversion of lysine AAG codons to arginine AGA codons requires two point mutations. Although point mutations play an established role in the rapid evolution of these proteins (24), it is unlikely that such a high number of mutations could be directed only to the C-terminal tail of this protein. If the evolution that resulted in these two proteins had occurred by point mutation alone, a minimum of 90 cumulative nucleotide substitutions would be required to achieve such a radical shift in lysine and arginine content. Examination of the nucleotide sequences of both the Styela and Ciona P1 gene indicates it is much more likely that a frameshift mutation occurred in the C-terminal region of a lysine-rich sperm-specific H1 that resulted in the distinctive sequence of the Styela P1. The same type of frameshift has not occurred in the evolution of the Ciona P1. However, deletion of a single nucleotide at position 342 and two nucleotides at position 437 of the coding region of the C. intestinalis P1 creates a frameshift mutation with surprising consequences (Fig. 4C). The arginine content of the C-terminal tail would effectively increase from 25.3% to 42.6%, with the net conversion of 15 lysine residues to arginine residues. In turn, this mutation would decrease the lysine composition from 46.3% to 25.5%, reflecting the observed compositional differences between the Styela and Ciona P1 proteins. This phenomenon represents a relatively uncharacterized mode of rapid protein evolution, particularly in its implications. Although it has been suggested that there may be frameshift evolutionary relationships between protein sequence families (25), we could find no previous described instance of such a significant and functional conversion due to frameshift mutations.

As seen in Fig. 4C, whereas the frameshift mutation creates a protein with elevated arginine content, it also introduces other sequences that do not generally occur in somatic histone H1s. First, there are two instances of SPRR, motifs not found in human protamines but seen in vertebrate protamines such as the chicken and newt P1 protamines (1) (Fig. 3C). These sequences are also very well represented in the sperm-specific histones of the sea urchin (26). The presence of valine in the frameshift mutant is also reflected in the protamines of chicken and newt P1 protamines (1). The presence of glutamic acid, however, is not seen in any SNBPs. It is very likely that, should this amino acid be introduced by frameshift mutation, it would be modified by a simultaneous point mutation.

Despite the sporadic occurrence of protamines in the animal kingdom, it is clear that selection for arginine in the SNBPs is in part due to its DNA-binding capabilities. Although lysine could also presumably perform this function, it has been reported that an increase in arginine content at the expense of lysine residues increases the affinity of a protein for DNA (27, 28). In addition to its positively charged moiety, arginine has a greater flexibility in the formation of hydrogen bonds with the DNA backbone due to its complex guanidinium group (29). Evolution of an arginine-rich protamine could also be the result of its involvement at the time of sperm-egg fertilization. It has been shown that proteins containing polyarginine tracts have the ability to activate casein kinase II (30), an important regulator of cellular metabolism in the developing egg.

In summary, the results presented in this paper provide unequivocal support to the notion that in chordates, the line that gave rise to protamines has in fact evolved from histones (4). Most importantly, they establish a hitherto elusive evolutionary link between the chromatin-condensing histone H1s of somatic tissues and the chromatin-condensing proteins of the sperm.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nancy Sherwood (Biology Department, University of Victoria) for kindly providing us with sperm samples from the tunicate C. intestinalis. This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Grant OGP 0046399 (to J.A.) and Ministerio Ciencia y Tecnologia/Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional Grant BMC2002-04081-C02-02 (to M.C. and N.S.).

Abbreviations: SNBP, sperm nuclear basic protein; PL, protamine-like.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AY332242).

References

- 1.Lewis, J. D., Song, Y., De Jong, M. E., Bagha, S. M. & Ausió, J. (2003) Chromosoma 111, 473–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felix, K. (1960) Adv. Protein Chem. 15, 1–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stedman, E. & Stedman, E. (1947) Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 12, 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subirana, J. A., Cozcolluela, C., Palau, J. & Unzeta, M. (1973) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 317, 364–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausió, J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31115–31118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ausió, J., Van Veghel, M. L., Gomez, R. & Barreda, D. (1997) J. Mol. Evol. 45, 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poccia, D. L., Simpson, M. V. & Green, G. R. (1987) Dev. Biol. 121, 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ausió, J. (1992) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 115, 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasinsky, H. E., Huang, S. Y., Mann, M., Roca, J. & Subirana, J. A. (1985) J. Exp. Zool. 234, 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itoh, T., Ausió, J. & Katagiri, C. (1997) Mol. Reprod. Dev. 47, 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saperas, N., Ausió, J., Lloris, D. & Chiva, M. (1994) J. Mol. Evol. 39, 282–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson, C. E. & Davies, P. L. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6157–6162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strickland, W. N., Strickland, M., Brandt, W. F., Von Holt, C., Lehmann, A. & Wittmann-Liebold, B. (1980) Eur. J. Biochem. 104, 567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wyckoff, G. J., Wang, W. & Wu, C. I. (2000) Nature 403, 304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanson, W. J. & Vacquier, V. D. (2002) Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jankowski, J. M., States, J. C. & Dixon, G. H. (1986) J. Mol. Evol. 23, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saperas, N., Chiva, M., Pfeiffer, D. C., Kasinsky, H. E. & Ausió, J. (1997) J. Mol. Evol. 44, 422–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jutglar, L., Borrell, J. I. & Ausió, J. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 8184–8191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saperas, N., Chiva, M. & Ausió, J. (1992) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 103, 969–974. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasinsky, H. E., Lewis, J. D., Dacks, J. B. & Ausió, J. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang, F., Lewis, J. D. & Ausió, J. (1999) Mol. Reprod. Dev. 54, 402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stach, T. & Turbeville, J. M. (2002) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 25, 408–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiva, M., Lafargue, F., Rosenberg, E. & Kasinsky, H. E. (1992) J. Exp. Zool. 263, 338–349. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torgerson, D. G., Kulathinal, R. J. & Singh, R. S. (2002) Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 1973–1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pellegrini, M. & Yeates, T. O. (1999) Proteins 37, 278–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poccia, D. L. & Green, G. R. (1992) Trends Biochem. Sci. 17, 223–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ausió, J., Greulich, K. O., Haas, E. & Wachtel, E. (1984) Biopolymers 23, 2559–2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puigdomenech, P., Martinez, P., Palau, J., Bradbury, E. M. & Crane Robinson, C. (1976) Eur. J. Biochem. 65, 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng, A. C., Chen, W. W., Fuhrmann, C. N. & Frankel, A. D. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 327, 781–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohtsuki, K., Nishikawa, Y., Saito, H., Munakata, H. & Kato, T. (1996) FEBS Lett. 378, 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiva, M., Rosenberg, E. & Kasinsky, H. E. (1990) J. Exp. Zool. 253, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramakrishnan, V., Finch, J. T., Graziano, V., Lee, P. L. & Sweet, R. M. (1993) Nature 362, 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells, D. & Brown, D. (1991) Nucleic Acids Res. 19, Suppl, 2173–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ausió, J., Soley, J. T., Burger, W., Lewis, J. D., Barreda, D. & Cheng, K. M. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]