Abstract

DNA arrays are capable of profiling the expression patterns of many genes in a single experiment. After finding a gene of interest in a DNA array, however, labor-intensive gene-targeting experiments sometimes must be performed for the in vivo analysis of the gene function. With random gene trapping, on the other hand, it is relatively easy to disrupt and retrieve hundreds of genes/gene candidates in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells, but one could overlook potentially important gene-disruption events if only the nucleotide sequences and not the expression patterns of the trapped DNA segments are analyzed. To combine the benefits of the above two experimental systems, we first created ≈900 genetrapped mouse ES cell clones and then constructed arrays of cDNAs derived from the disrupted genes. By using these arrays, we identified a novel gene predominantly expressed in the mouse brain, and the corresponding ES cell clone was used to produced mice homozygous for the disrupted allele of the gene. Detailed analysis of the knockout mice revealed that the gene trap vector completely abolished gene expression downstream of its integration site. Therefore, identification of a gene or novel gene candidate with an interesting expression pattern by using this type of DNA array immediately allows the production of knockout mice from an ES cell clone with a disrupted allele of the sequence of interest.

With the animal genome sequencing projects approaching their completion, the next big task for the bioscience research community is to rapidly and efficiently understand physiological functions in animals of the vast number of newly discovered genes and gene candidates.

DNA arrays are capable of profiling expression patterns of tens of thousands of genes simultaneously in a single experiment (1–3). With DNA arrays, it is possible to obtain a global view of gene expression, and a large number of genes have already been identified based on their interesting expression patterns. However, even a full description of the expression pattern of a gene in an animal does not permit us a complete understanding of its physiological function. Labor-intensive gene-targeting experiments sometimes must be performed after finding a gene with an interesting expression pattern to obtain mouse ES cell clones with a disrupted allele of the gene, from which knockout mice are produced for the in vivo analysis of the gene function. Another disadvantage of DNA arrays is the fact that unidentified genes are all neglected in experiments with standard DNA arrays, because such DNA arrays are constructed on the basis of information stored in the public databases for functional genes.

Gene trapping, on the other hand, is a form of random insertional mutagenesis specifically designed to disrupt and retrieve genes in target cells by producing intragenic vector integration events (4, 5). Hundreds or even thousands of genome sequences in mouse ES cells can be “trapped” in a relatively short period (6, 7). One type of gene trap approach is based on the promoter/enhancer trap, in which the expression of a promoterless selectable marker (like NEO or Hygro) depends on the capture of an active transcriptional promoter/enhancer in the target cells (8, 9). Although the promoter/enhancer trap is a very reliable way to focus exclusively on functional genes, transcriptionally silent genes in the target cells are missed by this strategy.

Another way to select for intragenic vector integration is to employ a polyadenylation [poly(A)] trap. In this case, an mRNA transcribed from a selectable marker gene lacking a poly(A) signal in a gene trap vector is stabilized only when the gene trap vector captures a cellular poly(A) signal (6, 10–13). Because poly(A) trapping occurs independently of target gene expression, any gene can potentially be identified with almost equal probability, regardless of the relative abundance of its transcripts in target cells.

In standard large-scale gene trap projects employing either the promoter/enhancer trap, poly(A) trap, or both of these strategies, only the nucleotide sequences and not the expression patterns of the trapped DNA segments are determined (6, 7). In such cases, potentially important gene-disruption events cannot be identified, especially for sequences without any identity/homology to other functional genes in the public databases.

Here we report the synergistic coupling of random gene [poly(A)] trapping and expression profiling with DNA arrays. We first created a large panel of randomly gene-trapped mouse ES cell clones and then constructed arrays of cDNAs derived from the disrupted genes in which a significant number of genes (hereafter referred to as “unknown”) were included. Identification of a gene or novel gene candidate with an interesting expression pattern in such DNA arrays immediately allows the production of knockout mice by using an ES cell clone with a disrupted allele of the sequence of interest. Therefore, a large number of genes/gene candidates with interesting expression patterns can be identified and disrupted in mice within a very short period, facilitating our understanding of genetic pathways involved in a wide variety of biological phenomena in animals.

Materials and Methods

Gene Trapping in ES Cells. A variant of the RET gene trap vector (13) was constructed by (i) deleting the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) gene cassette, (ii) replacing the short form of the mouse RNA polymerase II gene promoter with its long form to obtain a higher level of NEO gene expression, and (iii) adding more of the authentic mouse hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase gene exon 8 sequence between the NEO gene and the downstream splice donor (further details of the vector structure are provided in Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). To produce recombinant retrovirus, the Plat-E packaging cell line was maintained as described (14) and transfected with the variant RET plasmid by using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche, Gipf-Oberfrick, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The culture supernatant was harvested 48–60 h after transfection, filtrated through a 0.45-μm filter (Pall), aliquoted, and frozen at –80°C. For retrovirus infection, 2 × 106 RF8 ES cells cultured as described (15) were incubated with 1.5 ml of undiluted retrovirus supernatant in the presence of 5–8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma) for 2 h at 35–37°C. For transfection, 2 × 107 RF8 ES cells were electroporated (at 0.25 kV and 500 μF with Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II) with 5–10 μg of the linearized gene trap vector, which had been removed from the bacterial plasmid backbone. The ES cells were supplemented with 200 μg/ml G418 (Nacalai, Kyoto) 36–48 h after infection or electroporation and selected for 7–10 d. Drug-resistant colonies were manually picked up into 24-well plates, expanded for the fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS; BD Biosciences) and RNA analyses, and frozen.

RNA Isolation and 3′ RACE. Total RNA was extracted from gene-trapped ES cells grown in 24-well plates by using Sepasol reagent (Nacalai) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT) (Invitrogen) was used to synthesize cDNA strands. We also performed 3′ RACE as described (13). Briefly, two rounds of hemi-nested PCR were carried out by using Advantage-GC2 cDNA polymerase mix (BD Biosciences). In the first round, the mixed cDNA template, NEO 2.8 primer (5′-TCGCCTTCTTGACGAGTTCTTCTGACC-3′), and AD primer (13) were used. In the second round, PCR product from the first round, NEO 3.0 primer (5′-GCGTCCACCTTTGTTGTTGGATATGCC-3′), and AD-plus primer (13) were used. The PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 94°C for 3 min; 2 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 72°C for 4 min; 2 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 70°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min; 2 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 68°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min; 34 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 66°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 2 min; and 1 cycle of 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and sequenced with NEO 3.5 primer (5′-GCGTCCACCTTTGTTGTTGGATATGCC-3′) and ABI 3100 sequencers (Applied Biosystems).

DNA Arrays. Experiments with DNA arrays were performed basically as described (16). Briefly, based on the nucleotide sequence information in the Nara Institute of Science and Technology (NAIST)rap database (http://bsw3.aist-nara.ac.jp/kawaichi/naistrap.html), a pair of gene-specific primers were synthesized for each of 280 genes/gene candidates trapped in ES cells, and cDNA probes (≈200 bp on average) were generated by PCR, in which initial 3′ RACE products of gene trapping were used as templates. Amplified cDNA probes were then transferred in duplicate onto 8-cm × 12-cm Hybond N+ nylon membranes (Pall) and fixed by UV crosslinking. To prepare radiolabeled cDNA targets, poly(A)+ RNAs were isolated from different sources and reverse transcribed with SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen), oligo dT12–18 primers, and 32P-dCTP (both from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Membranes were first prehybridized for 2 h at 65°C in PerfectHyb hybridization buffer (Toyobo, Osaka) containing denatured poly(A) (Amersham Pharmacia) and mouse Cot-1 DNA (Invitrogen). After alkaline digestion of RNA and heat denaturation, 32P-dCTP-labeled mixed cDNA targets (≈4 × 107 cpm) were added to the prehybridized membrane, and the hybridization was carried out for 14 h at 65°C. Membranes were washed twice with 2 × SSC (1× SSC = 0.15 M sodium chloride/0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7)/1% SDS at 65°C for 15 min, and twice in 0.1 × SSC/1% SDS at 65°C for 15 min. The membrane arrays were exposed to imaging plates that were scanned by the Fuji BAS-5000 imaging plate reader.

Knockout Mice. Gene-trapped ES cells were transferred by microinjection into 3.5-d mouse (C57BL/6) blastocysts, and the resulting chimeric male mice were bred to C57BL/6 females to achieve the germline transmission of the mutant allele. The agouti offspring were tested for transgene transmission by PCR with tail DNA, Advantage-GC2 cDNA polymerase mix (BD Biosciences), gene-specific primers γ-aminobutyric acid (gaba)-intron-R1 (5′-TCTGTTCACGGAGTGTTCCCTTACAGAG-3′) and gaba-intron-S3 (5′-TTGTCTCCAGAGCCCAAATAAGCACTCAACTA-3′), and vector-specific primer gag-f1 (5′-GGAGAGACGGGGCGGATGGAGGAAGAGGAGGC-3′). Additional gene-specific primers used later in the analyses of the knockout mice were 7F (5′-CTTTCCTGGGTCTCTTTCTGGATTGACC-3′), 8R (5′-CTTTCCCCTCCTGTTGAGTTGTTTCCAC-3′), 8F (5′-GATGTGTACATGTGGGTCAGCTCCCTCT T T-3′), and 9R (5′-ACAGGGGCT TCCTGTGAACTTTGTACTC-3′). All mice were maintained at the NAIST animal facility and analyzed in accordance with the institutional guidelines.

Results and Discussion

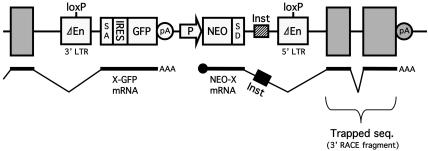

Genes and gene candidates in mouse ES cells were randomly disrupted by a variant of the RET gene trap vector (13) lacking the HSV-tk gene cassette (Fig. 1) to create a large panel of gene-trapped ES clones. Instead of using an enhancer/promoter trap strategy, the RET vector was designed to capture the poly(A) signal of cellular genes regardless of their expression status in target cells (13, 17). We determined the nucleotide sequences of ≈900 cDNA fragments derived from the trapped genes/gene candidates and established the NAISTrap database (http://bsw3.aist-nara.ac.jp/kawaichi/naistrap.html), in which several key features about the trapped gene are described for each ES cell clone. As shown in Table 1, the percentages of nonredundant (NR) (39.0%) and unknown (37.5%) genes identified in the NAISTrap project were higher and lower, respectively, than those previously reported for another large-scale poly(A)-trap projects with mouse ES cells (6). This difference would probably be due to the rapid maturation of public databases for functional genes in recent years. To assess the effectiveness of the RET vector as a disrupting element of gene function, the proportion of deleted mRNA was calculated for 82 well characterized NR genes randomly chosen from the NAISTrap database (Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). We realized that more than half (52.8% in average) of mRNA had been deleted because of gene trapping.

Fig. 1.

Structure of a variant of the RET gene trap vector. The vector uses an improved poly(A) (pA) trap strategy for the efficient identification of functional genes regardless of their expression status in target cells (13). Gray rectangles represent exons of the trapped gene X. A cDNA fragment of the trapped gene is retrieved as a 3′ RACE product by amplifying the downstream portion of the NEO-X fusion transcript. ΔEn, enhancer deletion; SA, splice acceptor; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; P, mouse RNA polymerase II gene promoter (long form); SD, splice donor; Inst, mRNA instability signal derived from the human granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene; X-GFP and NEO-X mRNAs, fusion transcripts generated from the 5′ half of the trapped gene X and the GFP cassette, and the NEO cassette and the 3′ half of the gene X, respectively.

Table 1. Genes and gene candidates identified in the NAISTrap project.

| Category | No. | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| NR genes | 182 | 39.0 |

| ESTs | 49 | 10.5 |

| Reverse strands of known genes | 23 | 4.9 |

| Repetitive sequences | 38 | 8.1 |

| Unknown sequences | 175 | 37.5 |

| Total | 467 | 100.0 |

In the NAISTrap project, discrete 3′ RACE bands were recovered from 75% of the total cellular RNA samples extracted from the ES clones that had been picked up after the RET vector introduction and G418 selection. Of the PCR products obtained, 69% produced “high-quality” DNA sequences. Homology searches were performed by the blastn algorithm with genome information from the public databases, including GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and Ensembl (http://www.ensembl.org). Identity or similarity extending more than ≈ 100 bp with the probability E value of 10-20 or less was considered to be significant homology. The results of initial 467 NAISTrap sequences are shown.

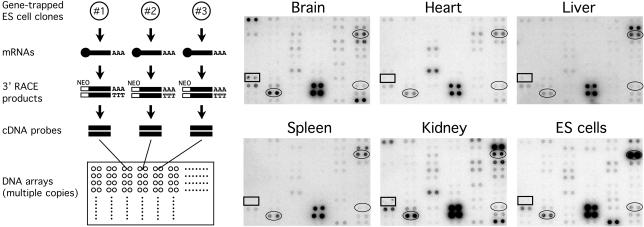

To obtain information about the expression patterns of the trapped genes in the mouse, we constructed membrane-based DNA (macro) arrays by including 280 cDNA fragments derived from randomly chosen NAISTrap clones (Fig. 2, see the above web site for details). As an initial model experiment, we searched for trapping events in ES cells of genes specifically expressed in the mouse brain. Identical sets of the DNA arrays were individually hybridized with radiolabeled mixed cDNA targets synthesized on mRNAs extracted from the mouse brain, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and ES cells. A comparison of the hybridization data was then made between mRNAs from different organs and ES cells, and five genes/gene candidates subsequently turned out to be exclusively expressed in the brain (Fig. 2). A closer examination of their nucleotide sequences revealed that one of them (derived from clone 2e-22) did not have its own counterpart in the public databases for functional mouse genes (i.e., NR genes and ESTs of the mouse). We would have failed to detect an interesting expression profile of the gene trapped in clone 2e-22 if we had used commercially available DNA arrays for expressed mouse genes, because such DNA arrays usually do not cover genes or gene candidates whose information is absent from the databases for functional mouse genes (data not shown). Interestingly, the nucleotide sequence of the DNA fragment isolated from clone 2e-22 showed 86% identity to a part of cDNA encoding the rat γ-aminobutyric acid receptor ρ3 subunit of unknown function (18). The predominant mRNA expression in the mouse brain of the gene disrupted in clone 2e-22 was confirmed by RT-mediated PCR (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 2.

Expression profiling of genes/gene candidates randomly trapped in mouse ES cells. Spots of clone 2e-22 and a couple of unknown genes are marked by rectangles and ovals, respectively. Amplified cDNA probes for 280 genes/gene candidates trapped in ES cells were transferred in duplicate onto a nylon membrane and hybridized with 32P-dCTP-labeled mixed cDNA targets generated with mRNAs from several mouse organs and ES cells. The results were verified by three independent experiments. Data for localized portions of the arrays containing the spots of clone 2e-22 are shown.

Fig. 3.

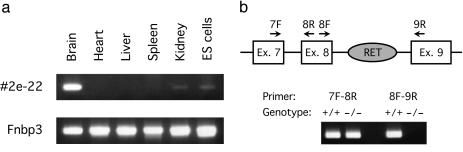

Expression of the gene trapped in clone 2e-22 in wild-type and mutant mice. (a) Tissue distribution of the gene expression in wild-type mice. RT-PCR was performed to detect mRNA of the gene trapped in clone 2e-22 in several organs of wild-type Institute for Cancer Research stock mice and in ES cells. Forward and reverse primers on exons 7 and 8, respectively, of the gene were used to amplify its mRNA. As an internal control, mRNA of Fnbp3 (19) was visualized by RT-PCR. (b) Complete disruption of the trapped gene in homozygous mutant mice. RT-PCR was performed to detect the two different mRNA portions of the gene trapped in clone 2e-22 in the brain of wild-type littermate and homozygous mutant mice. Four primers on exons 7, 8, and 9 were used as shown to amplify corresponding mRNA portions.

Because NAISTrap ES clones are valuable only if they retain germline colonizing capability, four independent clones, including 2e-22, were evaluated, and all four (2e-22, 1v-53, 2v-43, and 3v2–16) produced germline chimeras. Mice that were homozygous for the disrupted allele in clone 2e-22 were derived by mating heterozygous animals. Subsequent analysis revealed that the gene trap vector was inserted into intron 8 of the disrupted gene in clone 2e-22. We tested whether expression of a 3′ portion of the gene that is located downstream to the vector integration point had been completely abolished. RNA splicing between exons 7 and 8 was detected in the brain RNA by RT-PCR in both wild-type and homozygous mutant mice. However, splicing between exons 8 and 9 could only be detected in the wild-type animal (Fig. 3b), thereby demonstrating the strong disruptive nature of the RET gene trap vector (13). This feature is very important for a gene-trapping tool, because insertion of a single disrupting element in intron often does not result in the complete abolishment of the expression of downstream portions because of leaky transcription and splicing around the inserted element (20, 21).

In the case of standard DNA arrays, labor-intensive gene-targeting experiments sometimes must be performed after finding a gene with an interesting expression pattern to obtain ES cell clones with a disrupted allele of the gene. In contrast, discovering a gene in an array of randomly trapped sequences in ES cells means the establishment of an ES cell clone containing a disrupted allele of the corresponding gene. Thus, one can start producing knockout animals immediately after the gene discovery in DNA arrays based on random gene trapping in ES cells.

Another unique feature of the gene trap-driven DNA arrays is that they contain novel DNA sequences that cannot be classified as known (well-characterized) genes, genes whose expression has already been detected as ESTs, or homologs of genes in these two categories. In the NAISTrap project, such DNA sequences are marked as unknown genes, which constitute 37.5% of the whole trapped genes (Table 1). Commercially available DNA arrays, on the other hand, basically do not contain probe DNA for genes or gene candidates if their nucleotide sequences are not deposited in the NR or EST databases.

It is possible that many of these unknown sequences were found as artifacts in our gene trap strategy. However, at least some of them appear to be functional, because expression of these gene candidates was often directly detected in the DNA array experiments (Fig. 2) or indirectly by monitoring GFP expression in gene-trapped ES cell clones. More than one-third (25 of 67) of the unknown sequences in the initial DNA array gave rise to significant expression signals by using mRNA extracted from either one of the five mouse tissues examined or ES cells (data not shown). GFP expression driven by the promoter/enhancer activity of a trapped gene in a target cell (Fig. 1) was detected by flow cytometry in 48% (69 of 144) of the NAISTrap ES cell clones in which NR or EST genes had been trapped, suggesting that half of the functional genes trapped in our project are expressed in mouse ES cells (see the NAISTrap database for details). This number is compatible with the results from a previous analysis where the expression of ≈50% of known NR genes in a cDNA array was observed in mouse ES cells (22). By using this monitoring system, we were able to detect GFP expression in 24% (25 of 105) of the NAISTrap clones in which unknown sequences had been trapped (see the NAISTrap database for details). This again suggests that at least some of the unknown sequences identified in our project are functional because of their expression in ES cells.

For such sequences without any identity/homology to other functional genes in the public databases, one could overlook potentially important gene-disruption events if only the nucleotide sequence and not the expression pattern of the trapped DNA segments is analyzed, as is often the case with standard gene trap strategies (6, 7). It would be intriguing to examine the phenotype(s) of mice in which such unknown genes are homozygously disrupted.

Finally, it is worth noting that our gene trap-based DNA array strategy can be applicable to any other biological systems because cDNAs in our arrays were derived from randomly trapped genes and gene candidates regardless of their expression status in ES cells. To increase the value of our strategy, it is essential to multiply the number of gene-trapped ES cell clones and hence the number of probe cDNAs derived from the trapped genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Chainarong Tocharus, Mutsumi Tamura, and Nao Ekawa for their devotion in gene trap experiments, Dr. Hirotada Mori for guiding us to establish the NAISTrap database, Tomoko Ichisaka and Yukiko Samitsu for their help with blastocyst microinjection and animal care, Yumi Hirose for technical assistance, and Aaron B. Cowan for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research in Priority Areas “Genome Science” and “Infection and Immunity” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan and by research grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Suzuken Memorial Foundation.

Abbreviations: ES, embryonic stem; poly(A), polyadenylation; HSV-tk, herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase; RT, reverse transcriptase; NAIST, Nara Institute of Science and Technology; NR, nonredundant.

References

- 1.Brown, P. O. & Botstein, D. (1999) Nat. Genet. 21, 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duggan, D. J., Bittner, M., Chen, Y., Meltzer, P. & Trent, J. M. (1999) Nat. Genet. 21, 10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipshutz, R. J., Fodor, S. P. A., Gingeras, T. R. & Lockhart, D. J. (1999) Nat. Genet. 21, 20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans, M. J. (1998) Dev. Dyn. 212, 167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanford, W. L., Cohn, J. B. & Cordes, S. P. (2001) Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 756–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zambrowicz, B. P., Friedrich, G. A., Buxton, E. C., Lilleberg, S. L., Person, C. & Sands, A. T. (1998) Nature 392, 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiles, M. V., Vauti, F., Otte, J., Fuchtbauer, E. M., Ruiz, P., Fuchtbauer, A., Arnold, H. H., Lehrach, H., Metz, T., von Melchner, H. & Wurst, W. (2000) Nat. Genet. 24, 13–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Von Melchner, H. & Ruley, H. E. (1989) J. Virol. 63, 3227–3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedrich, G. & Soriano, P. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 1513–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niwa, H., Araki, K., Kimura, S., Taniguchi, S., Wakasugi, S. & Yamamura, K. (1993) J. Biochem. 113, 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida, M., Yagi, T., Furuta, Y., Takayanagi, K., Kominami, R., Takeda, N., Tokunaga, T., Chiba, J., Ikawa, Y. & Aizawa, S. (1995) Transgenic Res. 4, 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salminen, M., Meyer, B. I. & Gruss, P. (1998) Dev. Dyn. 212, 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishida, Y. & Leder, P. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita, S., Kojima, T. & Kitamura, T. (2000) Gene Ther. 7, 1063–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meiner, V. L., Cases, S., Myers, H. M., Sande, E. R., Bellosta, S., Schambelan, M., Pitas, R. E., McGuire, J., Herz, J. & Farese, R. V., Jr. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 14041–14046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard, K., Auphan, N., Granjeaud, S., Victorero, G., Schmitt-Verhulst, A. M., Jordan, B. R. & Nguyen, C. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 1435–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin, N. C., Ishida, Y., Hartford, S., Wnek, C., Bergstrom, R. A., Leder, P. & Schimenti, J. C. (2001) Nat. Genet. 28, 310–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogurusu, T. & Shingai, R. (1996) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1305, 15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan, D. C., Bedford, M. T. & Leder, P. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 1045–1054. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voss, A. K., Thomas, T. & Gruss, P. (1998) Dev. Dyn. 212, 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClive, P., Pall, G., Newton, K., Lee, M., Mullins, J. & Forrester, L. (1998) Dev. Dyn. 212, 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly, D. L. & Rizzino, A. (2000) Mol. Reprod. Dev. 56, 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.