Abstract

Stringent control mediated by the bacterial alarmone guanosine 5′-diphosphate 3′-diphosphate (ppGpp) is a key regulatory process governing bacterial gene expression. By devising a system to measure ppGpp in plants, we have been able to identify ppGpp in the chloroplasts of plant cells. Levels of ppGpp increased markedly when plants were subjected to such biotic and abiotic stresses as wounding, heat shock, high salinity, acidity, heavy metal, drought, and UV irradiation. Abrupt changes from light to dark also caused a substantial elevation in ppGpp levels. In vitro, chloroplast RNA polymerase activity was inhibited in the presence of ppGpp, demonstrating the existence of a bacteria-type stringent response in plants. Elevation of ppGpp levels was elicited also by treatment with plant hormones jasmonic acid, abscisic acid, and ethylene, but these effects were blocked completely by another plant hormone, indole-3-acetic acid. On the basis of these findings, we propose that ppGpp plays a critical role in systemic plant signaling in response to environmental stresses, contributing to the adaptation of plants to environmental changes.

The ability of organisms to survive under a wide range of adverse environmental conditions depends on diverse molecular mechanisms that adjust patterns of gene expression to the changing environment. In bacteria, one of the most important processes regulating gene expression is “stringent control,” which enables cells to adapt to nutrient-limiting conditions (1). The effector molecule of stringent control, called an alarmone, is a hyperphosphorylated guanosine nucleotide, guanosine 5′-diphosphate 3′-diphosphate (ppGpp), which binds to the core RNA polymerase, eventually leading to activation or repression of gene expression. Ribosome-dependent ppGpp synthesis is catalyzed by the relA gene product ppGpp synthetase (also called stringent factor), which is expressed in response to the binding of uncharged tRNA to the ribosomal A site (1). Likewise, plants have a complex signal transduction network activated in response to such stressful conditions as pathogenic infection, wounding, heat shock, drought, and high salinity (2, 3). Plant hormones such as ethylene, jasmonic acid, and abscisic acid occupy critical positions in this signal transduction network (4–7), although details on their molecular mechanisms remain unknown. Despite the apparent significance of ppGpp in bacterial gene expression, its importance in plant biology has been largely overlooked. By devising a system to measure small amounts of ppGpp precisely, however, we have been able to demonstrate unambiguously that ppGpp is produced in the chloroplasts of plant cells in response to stressful conditions.

Materials and Methods

Plant Seedlings and Green Algae. Pea, wheat, spinach, and rice seeds were grown on moist vermiculite at 25°C under white fluorescent light (12 h of light per day) for 3 weeks. In addition, Arabidopsis thaliana was grown for 6 weeks under the same conditions. Tobacco was grown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium containing 3% sucrose and 0.3% Gelrite (Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka) in a growth chamber at 25°C for 4 weeks. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii TW3 strain (thi10 cw15 mt+), which harbors the cell-wall deficiency mutation cw15, was cultured in Tris-acetate-phosphate medium at 25°C under continuous white fluorescent light with rotary shaking (8).

Abiotic Treatments. Plants were wounded by cutting the shoots a small interval with a knife. Treatment with salt, acid, alkali, or heavy metal entailed transplantation to an aqueous solution of NaCl (250 mM), HCl (pH 3.0), NaOH (pH 10.0), or CuSO4 (1 mM), respectively. For heat and cold treatment, temperature was shifted from 25 to 40 or 10°C. Plants were dehydrated by removing them from the soil and allowing them to dry at 25°C with humidity of <20%. For UV irradiation, plants were exposed to UV light (predominantly 254 nm) from a distance of 15 cm by using a germicidal lamp (15 W, National, Osaka). To treat them with plant hormones, plants were floated on an aqueous solution containing 0.3 mM (±)-jasmonic acid (Sigma–Aldrich), ethephon (an ethylene generator, Wako Pure Chemical), or (±)-abscisic acid (Sigma–Aldrich). Indole-3-acetic acid (Sigma–Aldrich) was added at a concentration of 0.1 mM. Plants were subjected to stress or hormone treatments for ≈1 or 2 h unless indicated otherwise.

ppGpp and Guanosine 5′-Triphosphate 3′-Diphosphate Analysis. To analyze levels of ppGpp and guanosine 5′-triphosphate 3′-diphosphate (pppGpp) in plants, shoots (20 g) from each plant to be tested were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, crushed, and extracted with 100 ml of 2 M HCOOH for 1 h at 4°C. After removing cell debris by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min) and filtration, water was added to the extract to give a final volume of 200 ml. This solution then was extracted further with 200 ml of water-saturated n-BuOH. For C. reinhardtii, 3.1 g of cells were collected by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 10 min), soaked in 20 ml of 2 M HCOOH, and sonicated for 5 min. After removing the cell debris by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 10 min), the supernatant was extracted with 20 ml of water-saturated n-BuOH. The water layer was applied immediately to an epichlorohydrin triethanolamine (ECTEOLA) cellulose column (10 ml, HCOO- form, Wako Pure Chemical), previously equilibrated with 1 M HCOOH, and eluted with 100 ml of 0.3 M HCOOH/0.3 M HCOONH4 followed by 30 ml of 2 M HCOONH4. The second effluent was charged onto Dowex 50W (50 ml, H+ form, Sigma–Aldrich), previously equilibrated with water, washed with 50 ml of water, and then lyophilized. The resultant residue first was dissolved in 4 ml of water and then extracted several times with an excess of n-BuOH to remove the water. The resultant concentrated solution (≈300 μl) was mixed with 40 μl of MeOH (to make the solution clear) and water to give a final volume of 400 μl. All procedures described above were carried out in a cold room (4°C).

To assay ppGpp, a portion (200 μl) of the extract solution was subjected to HPLC (L-7000, Hitachi, Tokyo) by using a Partisil SAX-10 column (4.6 × 250 mm, Whatman). The nucleotides were eluted at a flow rate of 1 ml/min by using a gradient made up of low (7 mM KH2PO4, adjusted to pH 4.0 with H3PO4) and high (0.5 M KH2PO4 plus 0.5 M Na2SO4, adjusted to pH 5.4 with KOH) ionic strength buffers. The proportion of the high ionic strength buffer was increased for 20 min from 0% to 100% and then maintained for 25 min at 100%. When assaying pppGpp, we used the same high ionic strength buffer but adjusted the pH to 4.0; pppGpp was eluted at 44 min. The recovery of ppGpp and pppGpp throughout the process was 20%, as estimated from results using standard ppGpp and pppGpp (purity >98%), which were prepared enzymatically in our laboratory by using Streptomyces morookaensis.

Analysis of ppGpp in Chloroplasts. Intact chloroplasts were isolated from untreated and wounded pea plants (150 g) in a cold room (4°C) by using the method of Perry et al. (9), after which the chloroplasts (300 mg) were soaked in 10 ml of 2 M HCOOH and then sonicated for 5 min. This solution then was extracted first with 10 ml of phenol saturated with water and then with 10 ml of chloroform. The water layer was freeze-dried, and the residue was then dissolved in 4 ml of water and concentrated by using an excess of n-BuOH. The resultant concentrate was used for ppGpp analysis. The recovery of ppGpp in this process was 80%, as estimated by using standard ppGpp.

RNA Polymerase Assay. Intact chloroplasts were prepared from pea plants (9). Purification of the DNA–protein complex for the RNA polymerase assay was done according to the method of Briat et al. (10). The DNA–protein complex (≈5–10 μg) was suspended in 20 μl of buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.6)/10 mM (NH4)2SO4/40 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/4 mM EDTA/25% glycerol/0.1% Triton X-100 and then incubated at 30°C for 1 h in thepresence of 30 μl of buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.9)/10 mM MgCl2/0.2 mM ATP/0.2 mM GTP/0.2 mM CTP/0.2 mM [3H]UTP [2 μCi/100 μl (1 Ci = 37 GBq)]/50 mM KCl. After running the reaction for the indicated times, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 30 μl of 1% sodium dodecylsulfate solution containing 50 mM sodium pyrophosphate. An aliquot (25 μl) was deposited on a DE81 DEAE cellulose filter (Whatman), and nucleotide triphosphates not incorporated into RNA were removed by washing the filter six times with 5% Na2HPO4, twice in water, and finally once in 99% ethanol. Radioactivity was measured by using a liquid scintillation counter.

Results

Existence of ppGpp in Plants. The analysis of ppGpp in bacteria was carried out by directly injecting the formic acid extracts into HPLC (11). However, because we would expect the level of ppGpp present in plants to be much lower than in bacteria, if it was there at all, we devised a method for pretreating samples that eliminated impurities (e.g., GTP and ATP, which hamper the ppGpp assay) and concentrated the ppGpp. This entailed subjecting the formic acid extracts to centrifugation, filtration, n-BuOH extraction, ion-exchange chromatography, and freeze-drying before HPLC (see Materials and Methods).

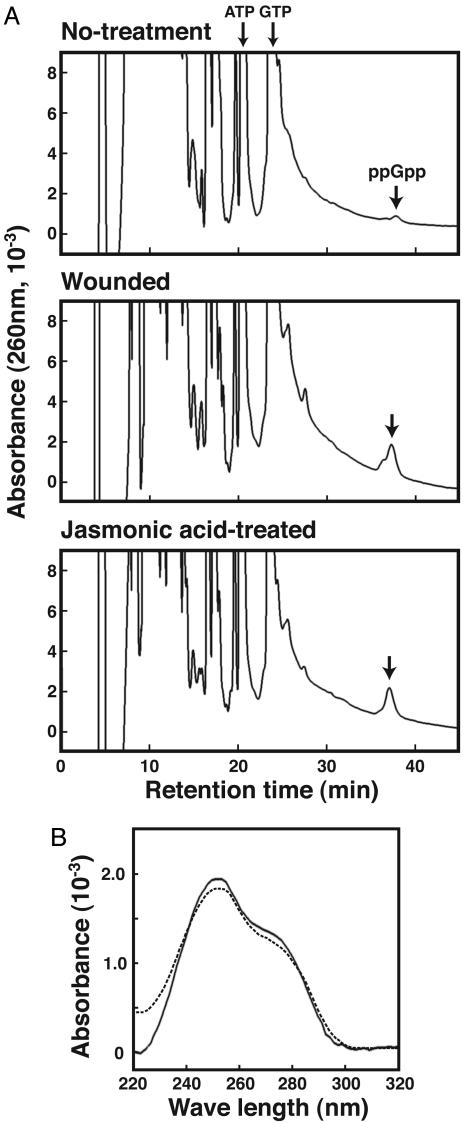

We first analyzed the endogenous ppGpp levels in pea plants and detected a peak with a retention time of 38.0 min (Fig. 1A). This retention time as well as the UV spectrum (Fig. 1B) coincided with those of our ppGpp standard and thus demonstrated the presence of ppGpp in pea. This finding was confirmed further by comigration of the substance with standard ppGpp in ionic strength buffer at lower (4.0) and higher (7.0) pH values and by the lability of the substance in both acidic and alkaline solutions; both the substance and the standard ppGpp were degraded completely by treatment with 0.1 M NaOH or 1 M HCl for 12 h at room temperature (data not shown). The level of ppGpp in pea was ≈5.6 pmol/g, which is 100- to 500-fold less than in bacteria (11, 12). By contrast, the levels of ATP and GTP were 14.6 and 2.32 nmol/g, respectively, as measured by direct assay of the formic acid extract.

Fig. 1.

Evidence for the existence of ppGpp in plants. (A) HPLC chromatograms of formic acid extract from a pea plant that was untreated (Top), wounded (Middle), or treated with jasmonic acid (Bottom). (B) The UV spectrum of the peak at 38.0 min was measured in an HPLC system equipped with a diode-array detector. The dotted line represents the spectrum of the ppGpp standard.

ppGpp Is Localized in Chloroplasts. Chloroplasts, which are believed to have originated from cyanobacteria, are a common element linking plants and bacteria (13). It is noteworthy that early reactions in the synthesis of jasmonic acid take place within chloroplasts (14) and that Chlamydomonas Cr-RSH, a homologue of bacterial RelA/SpoT (which catalyzes ppGpp synthesis), the gene of which is encoded in the nucleus, contains a conserved chloroplast-transit peptide, enabling translocation of the protein from the cytosol into chloroplasts (8). When we analyzed the ppGpp content of chloroplasts, we found the level to be 292 pmol/g, much higher than in the shoots (5.6 pmol/g) (Table 1). Given the difference in efficiency with which ppGpp was extracted from chloroplasts and shoots (see Materials and Methods), we estimate the actual difference in the levels of ppGpp to be ≈13-fold, which suggests that at least most of the ppGpp in pea is localized to the chloroplasts.

Table 1. Detection of ppGpp in plants and a green algae.

| ppGpp, pmol/g

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials | Untreated | Wounded | Jasmonic acid-treated |

| Pea | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 27.9 ± 3.2 | 31.2 ± 8.6 |

| Pea (etiolated) | <0.2 | <0.2 | <0.2 |

| Chloroplast (pea) | 292 | 1874 | NT |

| A. thaliana | 32.3 ± 1.8 | 145 ± 1.2 | NT |

| Spinach | 3.5 | 10.6 | NT |

| Tobacco | 0.6 | 7.3 | NT |

| Rice | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 17.4 ± 2.1 | 14.8 |

| Wheat | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 15.1 |

| C. reinhardtii | 20.3 | NT | NT |

Levels of ppGpp in various plants, Chlamydomonas, and pea chloroplasts were detected by HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. In some cases, plants were wounded by cutting or treated with 0.3 mM (±)-jasmonic acid. After HPLC analysis, the amount of ppGpp was determined by comparison with the peak area obtained with a standard ppGpp sample. Means ± SD of three separate experiments are shown. NT, not tested.

Wounding Induces ppGpp Accumulation. Arabidopsis At-RSH1, another homologue of relA/spoT, has been implicated in the responses of plants to stresses such as wounding, pathogenic infection, osmotic shock, and drought (15). We therefore tested the effect of wounding and found it to cause a 5-fold increase in ppGpp (Fig. 1 A and Table 1), with chloroplasts containing 1,874 pmol/g ppGpp, which is comparable with the levels found in nutritionally starved bacterial cells (≈5,000–50,000 pmol/g) (11, 16). [The shoulder detected in the ppGpp peak likely represents deoxy-ppGpp; the deoxy forms of nucleotides are known to be eluted just before each corresponding nucleotide in this HPLC system (17).] In contrast, no marked increase in ppGpp was detected when wounding treatment was performed in the dark or at 4°C as reference experiments (data not shown).

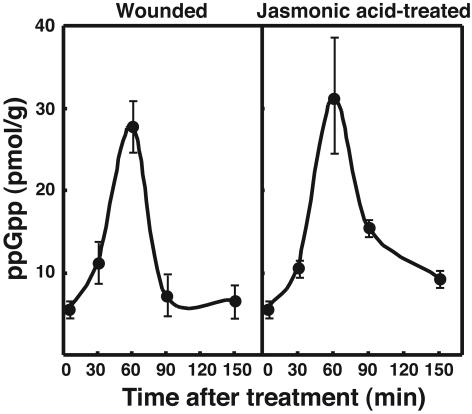

Wounding is also known to induce transient activation of jasmonic acid-regulated defensive gene expression in plants (18). Jasmonic acid is a potent second messenger in plants that mediates responses to wounding and pathogenic infection (19, 20) and was shown recently to induce expression of a defenserelated gene in rice that is homologous to At-RSH2 (21). Consistent with those earlier studies, treatment with jasmonic acid, similar to wounding, elicited a marked increase in ppGpp levels (Fig. 1 A), which suggests that wound-induced ppGpp accumulation was mediated via a jasmonic acid pathway. The increase in ppGpp elicited by both wounding and jasmonic acid treatment was transient and reached a maximum within 60 min (Fig. 2), suggesting the presence of a ppGpp-degrading system in plant cells, just as there is in bacteria (1, 11).

Fig. 2.

Changes in ppGpp content of pea plant after wounding or treatment with jasmonic acid. Pea plants were maintained at 25°C for the indicated times under light after each treatment and then subjected to the ppGpp assay. Error bars represent SD of three separate experiments.

When nutritionally starved, bacterial cells accumulate pppGpp as well as ppGpp (1, 11). Likewise, pppGpp was detected in wounded pea shoots, although its level was only approximately one-fourth (7.1 pmol/g) that of ppGpp (data not shown).

ppGpp Is Ubiquitous Among Plants. In addition to pea, ppGpp was found in several other plants tested, although the levels varied substantially, ranging from 0.6 pmol/g in tobacco to 32 pmol/g in Arabidopsis (Table 1). Neither ppGpp nor pppGpp was detected in dark-grown (etiolated) seedlings. Notably, marked increases in ppGpp levels were always elicited by wounding the shoots of Arabidopsis, spinach, tobacco, rice, and wheat. Moreover, the unicellular photosynthetic eukaryote C. reinhardtii, which expresses the relA/spoT homologue Cr-RSH (8), also contained high levels of ppGpp. On the other hand, when assayed by using cells in the early or late growth phase in an appropriate medium, our analytical method (detection limit: 0.2 pmol/g) failed to detect ppGpp in a pair of microbial eukaryotes, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) and Penicillium notatum (fungus).

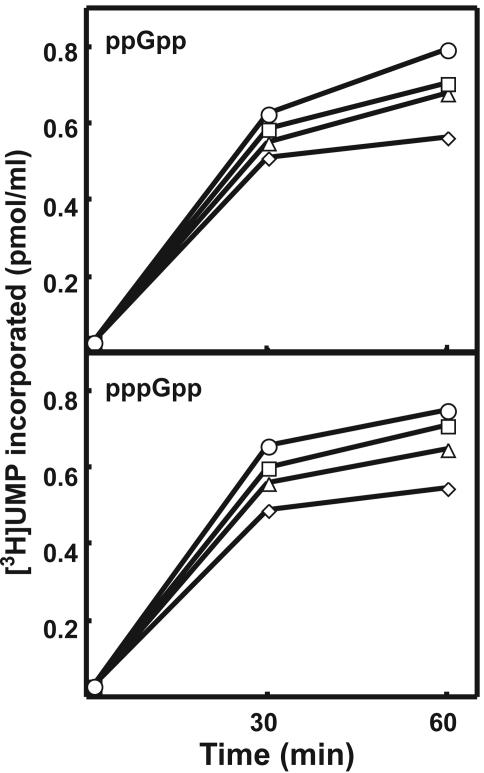

ppGpp Inhibits Chloroplast RNA Polymerase Activity. Plant cells have a eubacteria-like core RNA polymerase encoded in chloroplasts and a bacteriophage-like RNA polymerase encoded in the nucleus (13). In bacteria, one of the principle actions of ppGpp is inhibition of RNA polymerase, which in turn provokes the typical stringent response (1). Because there is evidence that chloroplast RNA synthesis in Chlamydomonas may be controlled by stringent conditions (22), we tested whether ppGpp would inhibit chloroplast RNA polymerase activity in vitro. We found that, indeed, ppGpp (≈0.5–2 mM) dose-dependently inhibited the RNA polymerase activity (Fig. 3), thus demonstrating the existence of a bacteria-type stringent response in pea chloroplasts. Likewise, pppGpp was also found to be as potent as ppGpp in inhibiting RNA polymerase activity.

Fig. 3.

Effect of ppGpp and pppGpp on in vitro RNA synthesis in chloroplasts. DNA–protein complexes from pea chloroplasts were incubated in the presence of [3H]UTP and various concentrations of ppGpp or pppGpp: ○, no ppGpp or pppGpp; □, 0.5 mM; ▵, 1 mM; ⋄, 2 mM. Each data point at 30 and 60 min represents the mean of four separate experiments. SD values (not shown) were within ±0.02 pmol/ml.

Light Conditions Influence ppGpp Levels. Chloroplasts are well known to play a central role in photosynthesis. When we examined the effect of light on ppGpp accumulation (Table 2), we found that, depending on the lighting condition, levels of ppGpp varied from 1.0 to 11.5 pmol/g. The change was especially prominent when the plant was suddenly placed in darkness after prolonged (12-h) light exposure, which elicited a marked increase in ppGpp. By contrast, prolonged (12-h) darkness caused a 5-fold reduction of ppGpp content, which is consistent with the fact that light is essential for translocation of RelA/SpoT from the cytoplasm into chloroplasts, as demonstrated in Chlamydomonas (23).

Table 2. Effect of lightning conditions on ppGpp accumulation in pea.

| Treatment | ppGpp, pmol/g |

|---|---|

| Light (12 h) (control) | 5.6 ± 0.7 |

| Light (12 h) to dark (1 h) | 11.5 ± 4.4 |

| Dark (12 h) | 1.0 ± 0.7 |

| Dark (12 h) to light (1 h) | 4.3 ± 1.9 |

Details of each treatment are described in Materials and Methods. The values are means ± SD of three separate experiments.

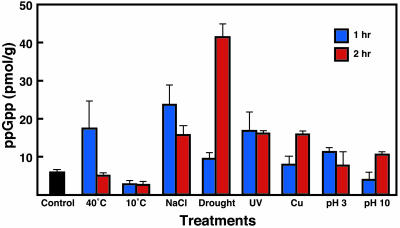

Plant Hormones Control ppGpp Levels. It was of interest to us that, similar to wounding, various physical stresses including heat shock, excess salinity, acidity, drought, UV irradiation, and heavy metal treatment all markedly increased ppGpp levels (Fig. 4). Drought (2 h) was the most effective stimulus, increasing ppGpp to 41 pmol/g. On the other hand, cold had no effect on ppGpp levels, perhaps because it lowered the cells' metabolic activity.

Fig. 4.

Accumulation of ppGpp in pea after various physical treatments. Unless stated especially, each treatment was performed at 25°C for 1 and 2 h under light. Details of each treatment are described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent means ± SD of three separate experiments.

In addition to jasmonic acid, two other plant hormones, ethylene and abscisic acid, are believed to participate in the signaling elicited by environmental stresses (7, 24, 25). We therefore tested the effect of those hormones on ppGpp accumulation and found that they too elicited 5- to 7-fold increases in ppGpp (Table 3). This hormone (jasmonic acid)-induced increase in ppGpp levels was abolished completely by pretreatment with cycloheximide, an antibiotic that specifically inhibits protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells (26). Surprisingly, another plant hormone, indole-3-acetic acid (belonging to the auxin group), did not elicit increases in ppGpp; instead, it markedly suppressed increases elicited by jasmonic acid, abscisic acid, or ethylene (Table 3). This antagonism between indole-3-acetic acid and other plant hormones was still apparent even after the concentration of indole-3-acetic acid was lowered from 0.1 to 0.02 mM.

Table 3. Accumulation of ppGpp in pea after plant hormone treatments.

| Treatment | ppGpp, pmol/g |

|---|---|

| Water (1 h) (control) | 8.7 ± 3.3 |

| JA (1 h) | 31.2 ± 8.6 |

| JA + cycloheximide (1 h)* | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| ET (1 h) | 26.3 ± 4.5 |

| ET (2 h) | 19.3 ± 1.7 |

| ABA (1 h) | 40.0 ± 7.0 |

| ABA (2 h) | 14.6 ± 1.5 |

| IAA (1 h) | 6.3 ± 2.5 |

| IAA (2 h) | 7.7 ± 0.9 |

| JA + IAA (1 h) | 8.4 ± 2.0 |

| JA + IAA (2 h) | 12.1 ± 2.5 |

| JA + IAA (1 h)† | 7.4 ± 1.3 |

| ABA + IAA (1 h) | 6.0 ± 0.2 |

| ET + IAA (1 h) | 11.5 ± 1.5 |

Each treatment was done at 25°C under light. Details of each treatment are described in Materials and Methods. The values are means ± SD of three separate experiments. JA, jasmonic acid; ET, ethylene; ABA, abscisic acid; IAA, indole-3-acetic acid.

The pea shoots were pretreated with cycloheximide (0.5 mM) for 30 min before treatment with jasmonic acid/cycloheximide solution

Instead of 0.1 mM indole-3-acetic acid, 0.02 mM was used

Discussion

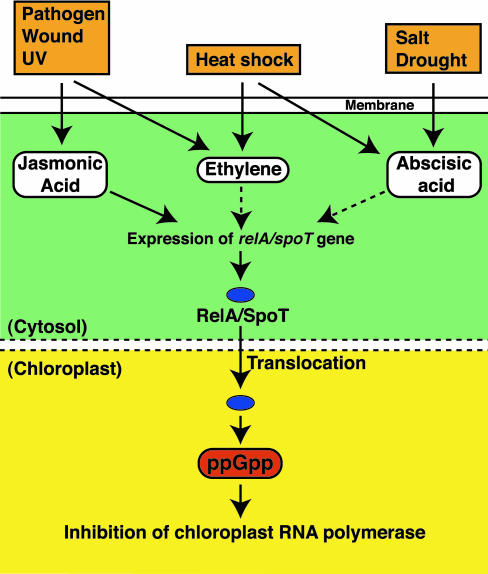

Although there has been considerable effort to definitively determine whether ppGpp is present in eukaryotes (27), the present study unambiguously identifies ppGpp in plants. Moreover, we observed substantial changes in ppGpp levels mediated by signals originating from physical stresses and hormones. The level of ppGpp in plants seems to be controlled strictly by a signal transduction network, as demonstrated by the inhibitory effect of indole-3-acetic acid. The schematic diagram in Fig. 5 was constructed based on the findings of this and earlier work and summarizes the intersecting signaling pathways activated in plants by stressful stimuli. It is also noteworthy that the effect of jasmonic acid was blocked completely by a eukaryotic protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide (Table 3), because it suggests that the effect of jasmonic acid is mediated by one or more proteins newly synthesized in the cytosol. This is in contrast to ppGpp accumulation in bacteria, which is triggered immediately in response to nutritional deficiency (i.e., increases in the fraction of uncharged tRNA) and reaches a maximum within 5–10 min (11, 12). The delayed (1-h; Fig. 2) increase in ppGpp levels seen in plants may be explained in this way. The suppressive effect of auxin may be due to the fact that, unlike other plant hormones, auxin is central to the control of growth (cell division, elongation, and differentiation) rather than to responding to stress. The present findings may offer intriguing insight into the antagonism between auxin and other plant hormones, as discussed by Swarup et al. (28).

Fig. 5.

Proposed model for ppGpp signal transduction in plants. The dotted-line arrows represent pathways that are not yet demonstrated experimentally.

Given the significance of ppGpp in bacterial physiology, ppGpp apparently plays a critical role in adjusting plant physiology. Our finding is consistent with recent works demonstrating the existence of relA/spoT homologues (At-RSH1 and Cr-RSH) in Arabidopsis and Chlamydomonas (8, 15). The proposed model (Fig. 5) suggests that the stringent response has been conserved through evolution and thus contributes to the adaptation of plants to environmental changes in a manner analogous to that seen in bacteria. In this regard, the salt tolerance of the halophyte Suaeda japonica was considered within the framework of the function of a plant relA/spoT homologue on the basis of Sj-relA/spoT expression in the yeast S. cerevisiae (29). Chloroplasts, a key organelle having many functions besides photosynthesis, are centrally involved in the defense systems of plants (30). Recent work in bacteria has shown that ppGpp plays a crucial role in initiating bacterial secondary metabolism, as represented by antibiotic production (31–33). Understanding in detail the functions of ppGpp and the signaling cascades it activates is clearly an important challenge that should provide important insight into plant evolution and adaptation to environmental changes and also should make a contribution in the area of plant breeding.

Note Added in Proof. During the editing of this paper, Givens et al. (34) reported the existence of homologues of bacterial relA/spoT genes in Nicotiana tabacum and inducibility of the relA/spoT gene expression after treatment with jasmonic acid.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Hosaka and H. Tsunekawa for preparation of standard ppGpp and pppGpp, and H. Hirano and K. Hasunuma for providing A. thaliana. This research was supported in part by a grant from the Organized Research Combination System of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to K.O.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: ppGpp, guanosine 5′-diphosphate 3′-diphosphate; pppGpp, guanosine 5′-triphosphate 3′-diphosphate.

References

- 1.Cashel, M., Gentry, D. R., Hernandez, V. J. & Vinella, D. (1996) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology, ed. Neidhardt, F. C. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), 2nd Ed., pp. 1458-1496.

- 2.Xiong, L., Schumaker, K. S. & Zhu, J. K. (2002) Plant Cell 14, Suppl., S165-S183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan, C. A. & Moura, D. S. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6519-6520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang, K. L., Li, H. & Ecker, J. R. (2002) Plant Cell 14, Suppl., S131-S151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liechti, R. & Farmer, E. E. (2002) Science 296, 1649-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner, J. G., Ellis, C. & Devoto, A. (2002) Plant Cell 14, Suppl., S153-S164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seo, M. & Koshiba, T. (2002) Trends Plant Sci. 7, 41-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasai, K., Usami, S., Yamada, T., Endo, Y., Ochi, K. & Tozawa, Y. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 4985-4992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry, S. E., Li, H. M. & Keegstra, K. (1991) Methods Cell Biol. 34, 327-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briat, J. F., Laulhere, J. P. & Mache, R. (1979) Eur. J. Biochem. 98, 285-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochi, K., Kandala, J. C. & Freese, E. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256, 6866-6875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ochi, K. (1987) J. Gen. Microbiol. 133, 2787-2795. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray, M. W. & Lang, B. F. (1998) Trends Microbiol. 6, 1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishiguro, S., Kawai-Oda, A., Ueda, J., Nishida, I. & Okada, K. (2001) Plant Cell 13, 2191-2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Biezen, E. A., Sun, J., Coleman, M. J., Bibb, M. J. & Jones, J. D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 3747-3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ochi, K. (1990) J. Bacteriol. 172, 4008-4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saito, N., Matsubara, K., Watanabe, M., Kato, F. & Ochi, K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5902-5911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seo, S., Okamoto, M., Seto, H., Ishizuka, K., Sano, H. & Ohashi, Y. (1995) Science 270, 1988-1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howe, G. A., Lightner, J., Browse, J. & Ryan, C. A. (1996) Plant Cell 8, 2067-2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vijayan, P., Shockey, J., Levesque, C. A., Cook, R. J. & Browse, J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7209-7214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong, L., Lee, M. W., Qi, M. & Yang, Y. (2001) Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 14, 685-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surzycki, S. & Hastings, P. J. (1968) Nature 220, 786-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrence, S. D. & Kindle, K. L. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20357-20363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ecker, J. R. (1995) Science 268, 667-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donnell, P. J., Calvert, C., Atzorn, R., Wasternack, C., Leyser, H. M. O. & Bowles, D. J. (1996) Science 274, 1914-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stocklein, W. & Piepersberg, W. (1980) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 18, 863-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverman, R. H. & Atherly, A. G. (1979) Microbiol. Rev. 43, 27-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swarup, R., Parry, G., Graham, N., Allen, T. & Bennett, M. (2002) Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 411-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada, A., Tsutsumi, K., Tanimoto, S. & Ozeki, Y. (2003) Plant Cell Physiol. 44, 3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seo, S., Okamoto, M., Iwai, T., Iwano, M., Fukui, K., Isogai, A., Nakajima, N. & Ohashi, Y. (2000) Plant Cell 12, 917-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun, J., Hesketh, A. & Bibb, M. J. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183, 3488-3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu, J., Tozawa, Y., Lai, C., Hayashi, H. & Ochi, K. (2002) Mol. Genet. Genomics 268, 179-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inaoka, T., Takahashi, K., Ohnishi-Kameyama, M., Yoshida, M. & Ochi, K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2169-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Givens, R. M., Lin, M. H., Taylor, D. J., Mechold, U., Berry, J. & Hernandez, V. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7495-7504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]