Abstract

Wilson’s disease is a rare disorder of copper transport in hepatic cells, and may present as cholestatic liver disease; pancreatitis and cholangitis are rarely associated with Wilsons’s disease. Moreover, cases of Wilson’s disease presenting as pigmented gallstone pancreatitis have not been reported in the literature. In the present report, we describe a case of a 37-year-old man who was admitted with jaundice and abdominal pain. The patient was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis, cholangitis, and obstructive jaundice caused by pigmented gallstones that were detected during retrograde cholangiopancreatography. However, because of his long-term jaundice and the presence of pigmented gallstones, the patient underwent further evaluation for Wilson’s disease, which was subsequently confirmed. This patient’s unique presentation exemplifies the overlap in the clinical and laboratory parameters of Wilson’s disease and cholestasis, and the difficulties associated with their differentiation. It suggests that Wilson’s disease should be considered in patients with pancreatitis, cholangitis, and severe protracted jaundice caused by pigmented gallstones.

Keywords: Wilson’s disease, Pancreatitis, Cholangitis, Obstructive jaundice, Cholestasis

Core tip: A 37-year-old male patient was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis, cholangitis, and jaundice caused by pigmented gallstones. Due to long-term jaundice and an obscure clinical course, the patient was evaluated for Wilson’s disease, which was confirmed using the Wilson’s disease score. This patient’s unique presentation exemplifies the overlap in the clinical and laboratory parameters of Wilson’s disease and cholestasis, and the difficulties associated with their differentiation. This very rare case of acute pancreatitis, as the presenting feature of Wilson’s disease, suggests that Wilson’s disease should be considered in patients with pancreatitis, cholangitis, and severe protracted jaundice caused by pigmented gallstones.

INTRODUCTION

Wilson’s disease is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder of copper transport in hepatic cells, with a reported incidence of 1: 30000[1,2]. The disease may present as a cholestatic liver disease[1,2] or, rarely, as hemolytic anemia[3-8]. Mild pancreatitis, upon presentation, has been described in only one case of Wilson’s disease and was attributed to copper deposition in the pancreas[9]. Cholelithiasis, as a result of hemolysis and pigmented gallstone formation, has also been reported in Wilson’s disease[10-19]. The atypical clinical presentation of cholangitis in patients with normal findings on bile duct imaging has also been reported[20]. However, pigmented gallstone pancreatitis and cholangitis, with concomitant obstructive jaundice, have not been reported as the presenting features of Wilson’s disease.

The diagnosis of Wilson’s disease in the setting of obstructive jaundice and cholestatic disease can be challenging because the laboratory and liver biopsy results overlap with those of other cholestatic conditions. In the present report, we describe the case of a patient who presented with acute pancreatitis (caused by pigmented gallstones), which was the first presenting feature of Wilson’s disease.

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old man was admitted to our hospital because of upper abdominal pain, jaundice, fever (39.6 °C), and diarrhea. He reported no prior exposure to drugs, alcohol, or chemicals. His physical examination revealed bilateral scleral icterus and jaundiced skin as well as abdominal tenderness without hepatosplenomegaly or abdominal masses. Moreover, there were no signs of chronic liver disease, such as spider naevi, clubbing, or caput medusae.

The results of the patient’s laboratory examination indicated a hemoglobin level of 14.5 g/dL (normal level: 14-18 g/dL), which decreased to 7.7 g/dL; a leukocyte count of 13.6-17.8 k/µL (normal level: 4.8-10.8 k/µL); a platelet count of 200 k/µL (normal level: 130-400 k/µL); a serum haptoglobin level of 128 mg/dL (normal level: 30-200 mg/dL); a reticulocyte count of 4% (normal level: 0.5-1.5%); reticulocyte production index 1.7 (normal index: 1); a serum amylase level of 2800 U/L (normal level: 28-100 U/L); a serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase level of 196 U/L (normal level: 0-35 U/L); and a glutamate pyruvate transaminase level of 78-150 U/L (normal level: 0-45 U/L). His results also demonstrated a serum alkaline phosphatase level of 312-812 U/L (normal level: 30-120 U/L), a total serum bilirubin level of 15.3-23.6 mg/dL (normal level: 0.3-1.2 mg/dL), a direct bilirubin of 7.2-17.0 mg/dL (normal level: 0-0.3 mg/dL), a serum C-reactive protein level of 170 mg/L (normal level: 0-5 mg/L), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 96 mm/h (normal level: 0-15 mm/h), a serum albumin level of 2.36 g/dL (normal level: 3.5-5.2 g/dL), a serum uric acid level of 1.5 mg/dL (normal level: 3.5-7.2 mg/dL), and a serum lactate dehydrogenase level that was within normal limits. The patient’s creatinine level at admission was 0.84 mg/dL (normal level: 0.67-1.17 mg/dL), and a blood film indicated anisocytosis and abnormal red blood cells. However, Heinz bodies were not observed.

Ultrasonography showed a thickened gallbladder wall and several hyperechoic foci, without any acoustic shadows in the gallbladder; the common bile duct was dilated to a diameter of 13.5 mm. Computed tomography (CT) showed a swollen pancreas with peripancreatic and pararenal fluid (Figure 1), a swollen gallbladder, choledochal dilation, and a choledochal stone.

Figure 1.

Abdominal computed tomography of the patient showing pancreatic edema and peripancreatic and pararenal fluid (arrow).

Negative results were noted on blood cultures, and the patient’s D-dimer level was 5484 ng/mL (normal level: 0-500 ng/mL). Level of clotting factor VII was low, at 8% (normal level: 60%-120%) whereas factor V and VIII level were normal, at 61% and 156%, respectively. Tests involving serum antibodies for hepatitis B and C viruses, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Coxiella burnetii, Brucella, and Rickettsia yielded negative results. Tests for serum anti-smooth muscle and anti-mitochondrial antibodies also yielded negative results.

The patient was intravenously treated with fresh frozen plasma, vitamin K, and antibiotic therapy, consisting of intravenous metronidazole (500 mg, 3 times/d) and intravenous ciproxin (200 mg, 2 times/d). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed and numerous pigmented, black stones were removed (Figure 2). However, his bilirubin level remained elevated, and other abnormal liver function test findings were noted. Acute renal failure [creatinine value increased to 4.60 mg/dL (normal level: 0.67-1.17 mg/dL)] and hypotension developed; therefore, treatment with norepinephrine was initiated. Another CT scan indicated the presence of hypoechoic foci in the liver. Due to a fair response and the long-term cholangitis, the antibiotic therapy was temporarily changed to intravenous amikacin (1 g/d) and intravenous ertapenem (1 g/d), and a marked clinical improvement was noted. The presence of pigmented gallstones, anemia, low serum uric acid levels, and protracted jaundice led to the suspicion of Wilson’s disease, even though hemolytic episodes had not been observed.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography of the patient showing removal of the stones by using a basket.

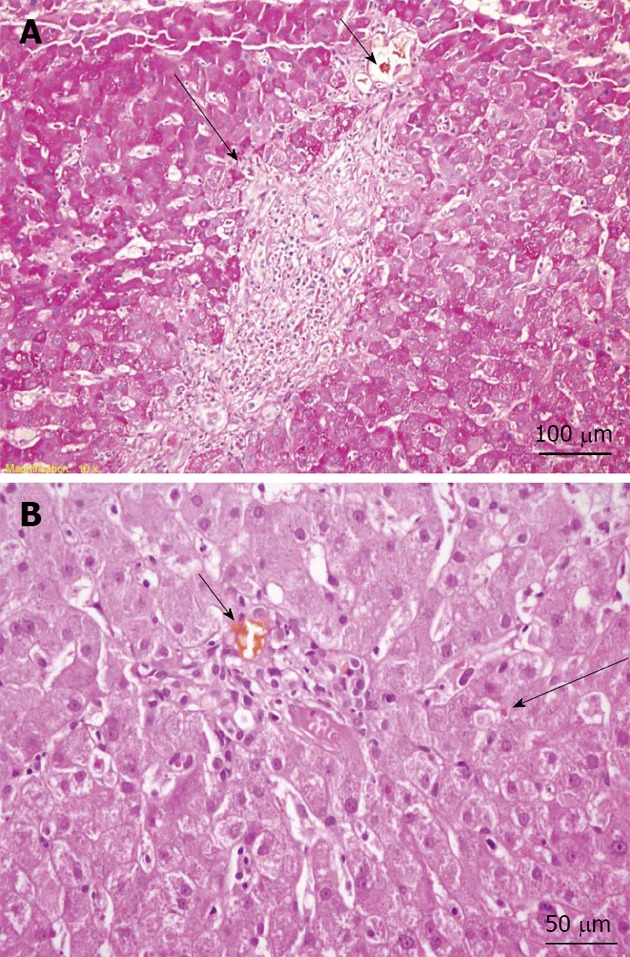

A slit lamp examination did not reveal Kayser–Fleischer rings. However, the patient’s ceruloplasmin level was 17 mg/dL (normal level: 20-45 mg/dL), and his 24-h copper excretion level was 305 µg (normal level: < 60 µg/24 h), which increased to 658 µg after trientine therapy was initiated. A liver biopsy showed chronic intrahepatic cholestasis, interface hepatitis, portal space lymphocytic plasma cells, and granulocyte infiltration (Figure 3); the hepatic copper content in the biopsy specimen was 304 µg/g (normal level: 10-35 µg/g ) dry weight. In addition, a molecular genetic analysis of a blood sample revealed a V1140A homozygous mutation in the ATP7B gene. Considering these results, a diagnosis of Wilson’s disease was established.

Figure 3.

Liver biopsy. A: Periodic acid Schiff-stained section (original magnification, × 200) showing mild interface hepatitis (long arrow) and a bile plug in the portal space bile duct (short arrow); B: Hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification, × 400) showing a bile plug in the portal space bile duct (short arrow) and mild intrahepatic cholestasis (long arrow).

Treatment with the chelating agent trientine (250 mg, 3 times/d) was initiated and antibiotic therapy with oral ciprofloxacin (250 mg, 2 times/d) was continued. The patient’s condition improved, and there were gradual improvements in the findings of the liver function tests, including normalization of the bilirubin and creatinine levels during the 6-mo follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

Wilson’s disease is an inherited disease, caused by one of several possible mutations in the ATP7B gene, leading to defective copper excretion into the bile and subsequent accumulation of copper in the liver and central nervous system. The hepatic manifestations of Wilson’s disease range from asymptomatic liver enzyme elevations to chronic, active hepatitis, cirrhosis, and acute fulminant hepatic failure[1,2]. Cholelithiasis has also been described in patients with Wilson’s disease[10-19], including one study that found cholelithiasis among 25% of Wilson’s disease patients[16]. Cholelithiasis is frequently observed in female patients with Wilson’s disease, but its incidence is not high among male patients with the disease. Acute cholangitis with bile duct stones has not been described in Wilson’s disease, although edema of the gallbladder, mimicking acute cholecystitis and clinical cholangitis, but with normal bile duct imaging findings, has been reported[17,20].

The diagnosis of Wilson’s disease in the presence of cholestasis or long-term bile duct obstruction is difficult and challenging. Many characteristic laboratory findings in Wilson’s disease overlap with those of other cholestatic conditions. Cholestasis, due to conditions such as chronic active hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis, results in elevated 24-h urine copper levels. In such cases, the hepatic copper content is usually elevated, but the ceruloplasmin level may be either normal or elevated[21-25]. However, even in cases of severe cholestasis, the 24-h urine copper level does not usually exceed 200 µg/24 h[2]; in the present patient, the copper level was 300 µg/24 h. Liver biopsies in patients with Wilson’s disease yield non-specific findings and may indicate chronic, active, hepatitis-like results. The Kayser-Fleischer ring may also be absent in 50% of patients with hepatic Wilson’s disease.

The molecular analysis conducted on a blood sample from the present patient showed a homozygous V1140A peptide change (nucleotide change, c.3419 T > C) mutation in the ATP7B gene. Over 500 mutations of the ATP7B gene have been reported to cause Wilson’s disease[2,26], some of which are very rare. These mutations lead to the production of defective copper transporter proteins, resulting in copper accumulation in the tissue. The V1140A mutation is a missense mutation, or sequence polymorphism in codon 3419 T > C of exon 16 on chromosome 13q, which was previously described in a Chinese, Czech-Slovakian, and Thai siblings and in a Yugoslavian cohort with Wilson’s disease[27-33].

A single, specific test for diagnosing Wilson’s disease does not exist. Therefore, the European Association for the Study of the Liver practical guidelines established a Wilson’s disease scoring system[21]. The diagnostic score is based on six available tests, including the presence of the Kayser-Fleischer ring, the presence of neurologic symptoms, ceruloplasmin values, the presence of hemolytic anemia, liver copper content in the absence of cholestasis, urinary copper levels, and a mutation analysis. A score of greater than or equal to four establishes a diagnosis of Wilson’s disease[21,34]; the present patient had a score of six, clearly indicating a diagnosis of Wilson’s disease. The low serum uric acid level found in our patient may be characteristic, although not diagnostic, of Wilson’s disease and is caused by renal tubular defects[2]. The reversible coagulopathy with anemia observed in the present patient has also been previously described in a patient with Wilson’s disease[20]. The pigmented gallstones associated with Wilson’s disease are related to hemolytic episodes and might be a presenting feature of the disease[2-8]. In the present patient, the reticulocyte production index was higher than normal whereas the serum haptoglobin level, which is usually decreased in patients with hemolysis, was within normal limits. We hypothesize that this may be due to the presence of acute pancreatitis and cholangitis, considering the fact that haptoglobin is characterized as an acute phase reactant.

In conclusion, Wilson’s disease should be considered in patients presenting with pancreatitis, cholangitis, and bile duct obstruction due to pigmented gallstones and who have protracted cholestasis and an obscure disease course.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Molinari M S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Ferenci P. Review article: diagnosis and current therapy of Wilson’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:157–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts EA, Schilsky ML. Diagnosis and treatment of Wilson disease: an update. Hepatology. 2008;47:2089–2111. doi: 10.1002/hep.22261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Członkowska A, Gromadzka G, Büttner J, Chabik G. Clinical features of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count syndrome in undiagnosed Wilson disease: report of two cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281:129–134. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aagaard NK, Thomsen KL, Holland-Fischer P, Jørgensen SP, Ott P. A 15-year-old girl with severe hemolytic Wilson’s crisis recovered without transplantation after extracorporeal circulation with the Prometheus system. Blood Purif. 2009;28:102–107. doi: 10.1159/000218090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liapis K, Charitaki E, Delimpasi S. Hemolysis in Wilson’s disease. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:477–478. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-1038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balkema S, Hamaker ME, Visser HP, Heine GD, Beuers U. Haemolytic anaemia as a first sign of Wilson’s disease. Neth J Med. 2008;66:344–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maple JT, Litin SC. 26-Year-old man with rapidly progressive jaundice and anemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:83–86. doi: 10.4065/77.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Khattabi A, Seddik H, Fatihi J, Salaheddine H, Badaoui M, Amézyane T, Mahassine F, Ohayon V. [Acute recurrent hemolytic anemia as the first manifestation of Wilson’s disease: Report of a case] Transfus Clin Biol. 2009;16:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weizman Z, Picard E, Barki Y, Moses S. Wilson’s disease associated with pancreatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:931–933. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198811000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhan O, Akpinar E, Oto A, Köroglu M, Ozmen MN, Akata D, Bijan B. Unusual imaging findings in Wilson’s disease. Eur Radiol. 2002;12 Suppl 3:S66–S69. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1589-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupuy R, Vallin J, Fabiani F. [2 cases of Wilson’s disease with hepatic precession in biliary lithiasis] Rev Int Hepatol. 1969;19:233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenfield N, Grand RJ, Watkins JB, Ballantine TV, Levey RH. Cholelithiasis and Wilson disease. J Pediatr. 1978;92:210–213. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walshe JM. Wilson’s disease: gall stone copper following liver transplantation. Ann Clin Biochem. 1998;35(Pt 5):681–682. doi: 10.1177/000456329803500515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh R, Sibal A, Jain SK. Gall stones, G-6PD deficiency and Wilson’s disease. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:635. doi: 10.1007/BF02722695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh JB, Chakrabarty S, Singh AK, Gupta D. Wilson’s disease--unusual features. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:937–938. doi: 10.1007/BF02830841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cançado EL, Rocha Mde S, Barbosa ER, Scaff M, Cerri GG, Magalhães A, Canelas HM. Abdominal ultrasonography in hepatolenticular degeneration. A study of 33 patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1987;45:131–136. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1987000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang SK, Chan CL, Yu RQ, Wai CT. Mimicry of acute cholecystitis from Wilson’s disease. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:e102–e104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akhan O, Akpinar E, Karcaaltincaba M, Haliloglu M, Akata D, Karaosmanoglu AD, Ozmen M. Imaging findings of liver involvement of Wilson’s disease. Eur J Radiol. 2009;69:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goswami RP, Banerjee D, Shah D. Cholelithiasis in a child--an unusual presentation of Wilson’s disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:1118–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wadera S, Magid MS, McOmber M, Carpentieri D, Miloh T. Atypical presentation of Wilson disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:319–326. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Association for Study of Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Wilson's disease. J Hepatol. 2012;56:671–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smallwood RA, Williams HA, Rosenoer VM, Sherlock S. Liver-copper levels in liver disease: studies using neutron activation analysis. Lancet. 1968;2:1310–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)91814-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritland S, Steinnes E, Skrede S. Hepatic copper content, urinary copper excretion, and serum ceruloplasmin in liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1977;12:81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benson GD. Hepatic copper accumulation in primary biliary cirrhosis. Yale J Biol Med. 1979;52:83–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gross JB, Ludwig J, Wiesner RH, McCall JT, LaRusso NF. Abnormalities in tests of copper metabolism in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:272–278. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosencrantz R, Schilsky M. Wilson disease: pathogenesis and clinical considerations in diagnosis and treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31:245–259. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu XQ, Zhang YF, Liu TT, Hsiao KJ, Zhang JM, Gu XF, Bao KR, Yu LH, Wang MX. Correlation of ATP7B genotype with phenotype in Chinese patients with Wilson disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:590–593. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i4.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gojová L, Jansová E, Külm M, Pouchlá S, Kozák L. Genotyping microarray as a novel approach for the detection of ATP7B gene mutations in patients with Wilson disease. Clin Genet. 2008;73:441–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loudianos G, Kostic V, Solinas P, Lovicu M, Dessì V, Svetel M, Major T, Cao A. Characterization of the molecular defect in the ATP7B gene in Wilson disease patients from Yugoslavia. Genet Test. 2003;7:107–112. doi: 10.1089/109065703322146786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vrabelova S, Letocha O, Borsky M, Kozak L. Mutation analysis of the ATP7B gene and genotype/phenotype correlation in 227 patients with Wilson disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang LH, Huang YQ, Shang X, Su QX, Xiong F, Yu QY, Lin HP, Wei ZS, Hong MF, Xu XM. Mutation analysis of 73 southern Chinese Wilson’s disease patients: identification of 10 novel mutations and its clinical correlation. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:660–665. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies LP, Macintyre G, Cox DW. New mutations in the Wilson disease gene, ATP7B: implications for molecular testing. Genet Test. 2008;12:139–145. doi: 10.1089/gte.2007.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Treepongkaruna S, Pienvichit P, Phuapradit P, Kodcharin P, Wattanasirichaigoon D. Mutations of ATP7B gene in two Thai siblings with Wilson disease. Asian Biomed. 2010;4:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferenci P, Caca K, Loudianos G, Mieli-Vergani G, Tanner S, Sternlieb I, Schilsky M, Cox D, Berr F. Diagnosis and phenotypic classification of Wilson disease. Liver Int. 2003;23:139–142. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]