Abstract

Context

Research across four decades has produced numerous empirically-tested evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) for youth psychopathology, developed to improve upon usual clinical interventions. Advocates argue that these should replace usual care; but do the EBPs produce better outcomes than usual care?

Objective

This question was addressed in a meta-analysis of 52 randomized trials directly comparing EBPs to usual care. Analyses assessed the overall effect of EBPs vs. usual care, and candidate moderators; multilevel analysis was used to address the dependency among effect sizes that is common but typically unaddressed in psychotherapy syntheses.

Data Sources

The PubMed, PsychINFO, and Dissertation Abstracts International databases were searched for studies from January 1, 1960 – December 31, 2010.

Study Selection

507 randomized youth psychotherapy trials were identified. Of these, the 52 studies that compared EBPs to usual care were included in the meta-analysis.

Data Extraction

Sixteen variables (participant, treatment, and study characteristics) were extracted from each study, and effect sizes were calculated for all EBP versus usual care comparisons.

Data Synthesis

EBPs outperformed usual care. Mean effect size was 0.29; the probability was 58% that a randomly selected youth receiving an EBP would be better off after treatment than a randomly selected youth receiving usual care. Three variables moderated treatment benefit: Effect sizes decreased for studies conducted outside North America, for studies in which all participants were impaired enough to qualify for diagnoses, and for outcomes reported by people other than the youths and parents in therapy. For certain key groups (e.g., studies using clinically referred samples and diagnosed samples), significant EBP effects were not demonstrated.

Conclusions

EBPs outperformed usual care, but the EBP advantage was modest and moderated by youth, location, and assessment characteristics. There is room for improvement in EBPs, both in the magnitude and range of their benefit, relative to usual care.

A half-century of treatment development research has produced an array of evidence-based psychotherapies (EBPs) for children and adolescents. These youth EBPs—i.e., treatments meeting multiple scientific criteria, including replicated support in randomized controlled trials (RCTs)—have been featured in numerous scholarly publications1-3 and governmental and professional association and academy websites.4,5 Many argue that EBPs should replace the usual treatments employed in everyday clinical care.6-8 Critics disagree,9-13 arguing that EBPs (a) have been tested mainly with subclinical youths and may not work well with the more serious, complex, diagnosed youths treated in real-world intervention settings; (b) are too rigidly manualized to permit the personalizing of treatment that professionals do in usual care; and (c) are mainly North American “western culture” products that may not travel well across ethnic, cultural, or national boundaries. Clearly, whether youth EBPs are superior or inferior to usual care is subject to debate.

This debate highlights a critical empirical question: When youth EBPs and usual care are compared directly to one another, does one form of treatment produce superior outcomes? The question is important scientifically, but also practically and clinically. Given the substantial cost of implementing most EBPs—with proprietary manual and measures, and lengthy training and supervision often required—potential users may reasonably ask whether EBPs reliably outperform usual care, and if so to what extent. Surprisingly, most RCTs cannot answer this question, because they have compared EBPs to waitlist or no treatment (passage of time) conditions, to attention-only control groups, or to psychological or medication placebo controls;2 those comparison conditions are all designed specifically to be weaker than the active treatment--controlling only for the passage of time, attention paid to the patient, or patient expectancies, and explicitly not designed to have beneficial therapeutic effects. By contrast, usual care is a stronger comparison condition because it entails an array of active interventions designed to produce genuine benefit to the patient.

Thus, comparisons of EBPs to usual care are not only important scientifically and clinically but they also represent a stronger standard for testing EBPs than other control groups do. To apply this strong standard, we identified 52 RCTs in which youths were randomly assigned to either EBPs or usual clinical care. This study collection is larger and meets more rigorous inclusion standards than any previous work on the topic.14,15 We conducted a meta-analysis of these 52 studies, assessing the effect of EBPs relative to usual care and testing candidate moderators of treatment benefit. To strengthen the analyses, we used a recently-developed multilevel approach to research synthesis that has not previously been applied to psychotherapy research. This allowed us to model the dependency among effect sizes that is common, but typically unaddressed, in psychotherapy meta-analysis.

Method

Data Sources, Study Selection, Inclusion Criteria

We searched for youth psychotherapy RCTs, encompassing internalizing (e.g., anxiety, depression) and externalizing (e.g., conduct, ADHD) dysfunction,16,17 first using PsycINFO and PubMed for January, 1960 – December, 2010. For PsycINFO we employed 21 psychotherapy-related key terms (e.g., psychother-, counseling) used in previous youth psychotherapy meta-analyses.18,19 PubMed's controlled indexing system (MeSH) searches publishers who may use different key words for the same concepts; we used Mental Disorders, with these search limits: clinical trial, child (3-18 years), published in English, and human subjects. Next we searched youth psychotherapy reviews and meta-analyses, followed reference trails, and obtained studies suggested by investigators in the field. Standard guidelines for performing meta-analysis20-22 recommend addressing publication bias partly by including unpublished studies of acceptable methodological quality. Dissertations are particularly appropriate because they are (a) free of publication bias; (b) reliably identifiable through systematic search of the Dissertation Abstracts International database; and (c) strong in methodological quality even when compared to published studies (perhaps partly because dissertations require faculty committee supervision).19 So, we searched Dissertation Abstracts International using the same search terms used for the published literature search.

From the studies retrieved, we identified all that compared an EBP to a usual care intervention. EBPs were defined as treatments listed in at least one of the published reviews systematically identifying evidence-based psychotherapies for youth based on level of empirical support.1,2,6,23-28 Usual care was defined as psychotherapy, counseling, or other non-medication intervention services provided through outpatient clinics, through public programs and agencies (e.g., child welfare, probation), and through residential facilities (e.g., inpatient, group home, detention) for youths. Usual care in which participants sought their own outside services were only included if the authors either facilitated service use (e.g., arranged intake appointments) or documented that equivalent percentages of usual care and EBP participants (i.e., not differing by more than 10%) received services. Other inclusion criteria were (a) participant psychopathology [mental disorder or elevated behavioral/emotional symptoms] documented through pre-treatment and post-treatment assessment; (b) random assignment to treatment conditions; and (c) mean age 3-18 years. We defined psychopathology as either meeting criteria for a DSM disorder (study years spanned the second, third, and fourth editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) or showing elevated behavioral/emotional symptoms, because both diagnostic and symptom approaches to operationally defining psychopathology are common in the youth treatment outcome literature. Youths who have elevated behavioral/emotional symptoms experience serious impairment,1,2,29,30 and are often referred to and treated in mental health clinics.3,31 Including both kinds of studies allowed us to test whether diagnosis required versus not required was a moderator of treatment effects.

Data Extraction

Studies were coded for study and sample characteristics, treatment procedures, and multiple candidate moderators of treatment outcome. To assess inter-coder agreement, 30 randomly selected studies were independently coded by three project coders. Agreement was good for both categorical codes (kappas.71 to .91) and continuous codes (ICCs.94 to .99).

Data Synthesis: Effect Size Calculation

Effect sizes (ESs) were represented as Cohen's d,32 reflecting the standardized mean difference between EBP and usual care. Most ES calculations were based on raw data reported in the studies or obtained by contacting study authors; we calculated the difference between the EBP and usual care group means, divided by the pooled SD. Positive ES implied an advantage for EBP over usual care. For studies reporting results using other metrics (e.g., frequencies, significance test results), we transformed data to d using Lipsey-Wilson22 procedures. Studies reporting only p-values or significant effects (assumed to reflect p < .05 if not otherwise stated) were assigned the minimum d that would achieve that significance level given the sample size. Studies merely reporting a non-significant effect were assigned d = 0. ES values were adjusted using Hedges' small sample correction.33

Data Synthesis: Rationale for, and Description of, the Multilevel Approach

Because most studies (89%) reported on multiple outcome measures and/or multiple time points, generating multiple effect sizes per study, the assumption of independence that underlies traditional meta-analytic approaches was violated.22 Common strategies to deal with dependent ESs have included averaging the ESs within studies, selecting only one ES from each study, ignoring the dependency, or applying a ‘shifting unit of analysis’ approach. These approaches either ignore or avoid dependency, and can distort meta-analytic results.34 In contrast, multilevel models can more appropriately address multiple ESs within the same study.35,36 Although multilevel models largely parallel traditional random-effects models,37 the former do not require independence of ESs; rather, dependence among multiple ESs within studies is modeled by adding an intermediate level. We used a three-level model, modeling the sampling variation for each ES (Level 1), variation over ESs within a study (Level 2), and variation over studies (Level 3). The basic model consists of three regression equations referring to each of the levels:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The first level equation (Equation 1) indicates that the jth observed ES from study k equals its population value, plus a random deviation, which is assumed to be normally distributed. In a meta-analysis this residual variance is estimated before performing the meta-analysis. The mean observed sampling variance of standardized mean difference (d) was used in this study; it equaled 0.105. The second level equation (Equation 2) states that the population values comprise a study mean and random deviation from this mean, which is again assumed to be normally distributed. At the third level (Equation 3), study mean effects are assumed to vary randomly around an overall mean.

We employed this extension of the commonly used random-effects meta-analytic model to obtain an overall estimate of the difference between EBP and usual care. Similarly to traditional mixed effects models, we subsequently fitted a three-level mixed effects model to identify moderators that might explain variation in ESs within and between studies by adding study (Level 3) or effect size (Level 2) characteristics as fixed predictors. Moderator analyses were only conducted if each category contained at least three studies. Because including multiple moderators with multiple categories may inflate Type II error rates,38 separate three-level mixed models were fitted for each moderator variable. Afterward, we fitted a three-level mixed effects model that included moderators found to be significant in the separate models, to address possible confounding among moderators.

Parameters estimated in a multilevel meta-analysis are the regression coefficients of the highest level equations and the variances at the second and third level. Fixed model parameters are tested using a Wald test, which compares the difference in parameter estimate and the hypothesized population value divided by the standard error with a t-distribution. For categorical variables with more than two categories, the omnibus test of the null hypothesis that the group mean ESs are equal follows an F-distribution. Likelihood ratio tests, comparing the deviance scores of the full model and models excluding variance parameters, were used to test variance components. Parameters were estimated using the restricted maximum likelihood procedure implemented in SAS PROC MIXED.39 Observed ESs were weighted by the inverse of the sampling variance, with a general Satterthwaite approximation used for the denominator degrees of freedom for tests of the regression coefficients.

Publication bias

We addressed risk of publication bias22,40,41 in four ways. First, we included unpublished dissertations (discussed above). Second, we compared mean ES for published studies versus dissertations; the difference was not significant t(53.9) = -0.70, p = 0.486. Third, we created a funnel plot;42 standard error was plotted on the vertical axis as a function of ES on the horizontal axis. The plot should resemble an inverted funnel with studies distributed symmetrically around the mean ES if publication bias is absent. With publication bias, the funnel plot should look asymmetrical.40 Our plot, tested using Egger's weighted regression test,43 was not asymmetrical, t(50) = 0.764, p = 0.447. Fourth, we computed a classic fail-safe N,41 which showed that 565 studies with mean ES=0 would need to be added to yield a nonsignificant summary effect. This exceeded Rosenthal's41 benchmark of 80 (5n + 10), suggesting that our findings are robust to the threat that excluded studies might have yielded a nonsignificant effect.

Methodological rigor

Methodological rigor was assessed using risk of bias criteria suggested by the Cochrane Collaboration21: (a) random sequence generation; (b) blinding of participants; and (c) completeness of outcome data (i.e., attrition rate). As less rigorous studies have been found to yield overestimates of ES,44 we tested whether ES differed according to the separate criteria. All studies passed the random sequence generation criterion, and there were no significant differences in mean ES on the blinding criterion, t(148) = -1.19, p = 0.235 or the completeness criterion (i.e., attrition rate < 40%), t(97) = -0.64, p = 0.523.

Results

Study Pool

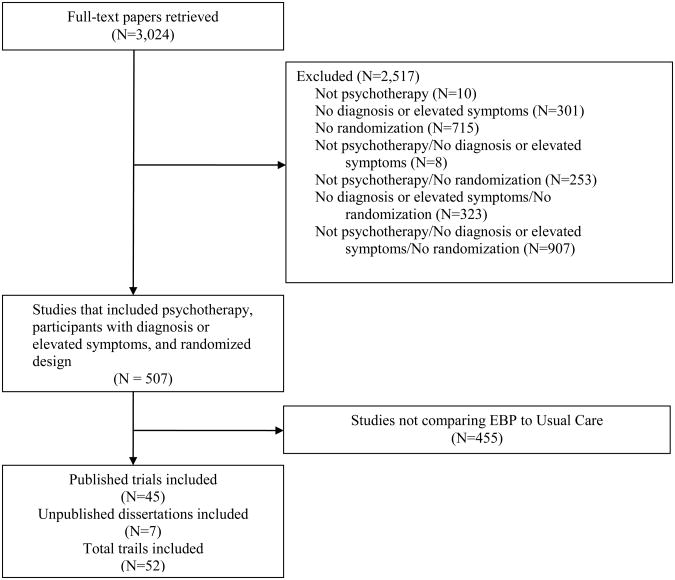

Our search yielded 52 RCTs (45 published trials, 7 dissertations) that met inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). These included 341 dependent ESs comparing EBPs to usual care.45-109 The studies, spanning 1973-2010, included 5,387 participants; mean group n was 48.10 (SD = 67.62), mean age 12.63 years (SD = 2.84), and mean percent males 62.67 (SD = 29.67). The types of EBP and usual care interventions are described within Table 1. Most studies (n=49) assessed outcomes post-therapy; 22 studies included follow-up assessment, ranging from 8-76 weeks after the end of treatment (M = 30.92, SD=18.74); three studies included only a follow-up assessment. Of those studies reporting race/ethnicity, Caucasians were the majority in 22, ethnic minorities in 15. More studies focused on adolescents (n = 37), than children (n = 15). Table 1 shows other study characteristics.

Figure 1. Flow Chart for the Search and Identification of Randomized Controlled Trials.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 52 Randomized Controlled Trials of EBP versus Usual Care Included in the Meta-Analysis.

| Study | Target Problem | Sample sizea | Mean Age | % Male | Type of EBP | Type of Usual Care | Mean ESb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander & Parsons (1973); Parsons & Alexander (1973); Klein, Alexander, & arsons (1977) | Delinquency | 65 | 14.5 | 44.2 | Behavioral Family Systems Therapy (later renamed Functional Family Therapy) | Usual outpatient services (client-centered family groups) Usual outpatient services(psychodynamic family therapy) |

0.24 |

| Asarnow, Jaycox, Duan, LaBorde, Rea, Murray, Anderson, Landon, Tang, & Wells (2005) | Depression | 344 | 17.2 | 22 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Quality Improvement Intervention) | Usual outpatient services | 0.18 |

| Bank, Marlowe, Reid, Patterson, & Weinrott (1991) | Delinquency | 54 | 14 | 100 | Behavioral Parent Training (Oregon Parent Management Training) | Usual outpatient services | 0.07 |

| Barrington, Prior, Richardson, & Allen (2005) | Anxiety | 48 | 9.99 | 35.19 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (for youths and for parents and family) | Usual outpatient services | 0.06 |

| Borduin, Schaeffer, & Heiblum (2009) | Delinquency: sexual offenses | 46 | 14 | 95.8 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual outpatient services | 0.80 |

| Borduin, Henggeler, Blaske, & Stein (1990) | Delinquency: sexual offenses | 16 | 14 | 100 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual outpatient services | 0.71 |

| Chamberlain & Reid (1998); Eddy & Chamberlain (2000); Eddy, Whaley & Chamberlain (2004) | Delinquency | 80 | 14.9 | 100 | Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care | Usual residential services | 0.46 |

| Davidson II (1976)* | Delinquency | 79 | 14.5 | 91.7 | Behavioral Contracting and usual care | Usual system/agency services | 0.40 |

| Deblinger, Lippmann, & Steer (1996); Deblinger, Steer, & Lippmann (1999) | Anxiety: PTSD | 46 | 9.8 | 17 | Cognitive behavioral therapy for youths Parent training in youth cognitive behavioral therapy and youth management skills Combination of cognitive behavioral therapy for youths and parent training |

Usual system/agency services | 0.53 |

| Diamond, Wintersteen, Brown, Diamond, Gallop, Shelef, & Levy (2010) | Depression | 60 | 15.1 | 16.66 | Attachment-Based Family Therapy | Usual outpatient services | 0.40 |

| Dirks-Linhorst (2003)* | Delinquency | 141 | 14.38 | 63.63 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual system/agency services | -0.07 |

| Emshoff & Blakely (1983); Davidson II, Redner, Blakely, Mitchell, & Emshoff (1987) | Delinquency | 136 | 14.2 | 83 | Behavioral contracting and advocacy | Usual system/agency services | 0.14 |

| Fleischman (1982) | Conduct problems | 64 | 7.5 | Not provided | Behavioral Parent Training (Oregon Parent Management Training) | Usual outpatient services | 0.00 |

| Garber, Clarke, Weersing, Beardslee, Brent, Gladstone, DeBar, Lynch, D'Angelo, Hollon, Shamseddeen, Iyenger (2009) | Depression | 123 | 14.8 | 41.5 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Coping With Depression Course-Adolescents) | Usual outpatient services | 0.27 |

| Gillham, Hamilton, Freres, Patton, & Gallop (2006) | Depression | 216 | 11.5 | 46.86 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Penn Resiliency Program) | Usual outpatient services | 0.17 |

| Glisson, Schoenwald, Hemmelgarn, Green, Dukes, Armstrong, & Chapman (2010) | Multiple problems | 191 | 14.9 | 69.1 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual outpatient and residential services | 0.03 |

| Grant (1987)* | Delinquency | 26 | 15.8 | 100 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Problem Solving Training and usual care) | Usual residential services | -0.25 |

| Hawkins, Jenson, Catalano, & Wells (1991) | Delinquency | 141 | 15.5 | 73 | Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT Skills TrainingCDE and usual care) | Usual residential services | 0.96 |

| Henggeler, Borduin, Melton, Mann, Smith, Hall, Cone & Fucci (1991); Henggeler, Melton, & Smith (1992); Henggeler, Melton, Smith, Schoenwald, & Hanley (1993) | Delinquency | 56 | 51.5 | 77 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual system/agency services | 0.68 |

| Henggeler, Pickrel, Brondino, & Crouch (1996); Brown, Henggeler, Schoenwald, Brondino & Pickrel (1999); Henggeler, Pickrel, & Brondino (1999) | Delinquency + Substance Abuse | 140 | 15.7 | 79 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual system/agency services | 0.27 |

| Huey, Henggeler, Rowland, Halliday-Boykins, Cunningham, Pickrel, & Edwards (2004) | Depression | 110 | 12.9 | 65 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual residential services | 0.08 |

| Jarden (1995)* | Conduct problems | 50 | 13.5 | 100 | Problem Solving Skills Training and usual care Problem Solving Skills Training, generalization component, and usual care |

Usual residential services | 0.27 |

| Leve, Chamberlain, & Reid (2005); Chamberlain, Leve, & DeGarmo (2007); Kerr, Leve, & Chamberlain (2009) | Delinquency | 81 | 15.3 | 0 | Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care | Usual residential services | 0.34 |

| Leve & Chamberlain (2007); Kerr, Leve, & Chamberlain (2009) | Delinquency | 83 | 15.3 | 0 | Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care | Usual residential services | 0.43 |

| Luk, Staiger, Mathai, Field, Adler (1998); Luk, Staiger, Mathai, Wong, Birleson, & Adler (2001) | Conduct problems | 30 | 8.6 | 62.5 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (parent-youth modification) Behavioral Family Systems TherapyE |

Usual outpatient services | -0.39 |

| Mann, Borduin, Henggeler, & Blaske (1990); Borduin, Mann, Cone, Henggeler, Fucci, Blaske, & William (1995) | Delinquency | 176 | 14.8 | 67.5 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual outpatient services | 0.48 |

| McCabe & Yeh (2009) | Significant behavior problems | 119 | 4.4 | 70.69 | Behavioral Parent Training (Parent-Child Interaction Therapy-standard) Behavioral Parent Training (Parent-Child Interaction Therapy-culturally modified) |

Usual outpatient services | 0.62 |

| Mclaughlin (2010)* | Depression | 22 | 11.82 | 59 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Coping With Depression Course-Adolescents) | Usual outpatient services | 0.25 |

| Morris (1981)* | Delinquency | 30 | 14.75 | 100 | Anger Control Program and usual care | Usual residential services | 0.26 |

| Ogden & Hagen (2008) | Conduct problems | 112 | 8.44 | 80.4 | Behavioral Parent Training (Oregon Parent Management Training) | Usual outpatient services | 0.15 |

| Ogden & Halliday-Boykins (2004) | Antisocial behaviors | 96 | 14.95 | 63 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual system/agency services and Usual residential services | 0.23 |

| Patterson, Chamberlain, & Reid (1982) | Conduct problems | 19 | 6.80 | 69 | Behavioral Parent Training (Oregon Parent Management Training) | Usual outpatient therapy | 0.46 |

| Rohde, Jorgensen, Seeley, & Mace (2004) | Conduct Problems | 64 | 16.3 | 100 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Coping With Depression Course-Adolescents) | Usual residential services | 0.05 |

| Rowland, Halliday-Boykins, Henggeler, Cunningham, Lee, Kruesi, & Shapiro (2005) | Serious emotional disturbance | 31 | 14.5 | 58 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual outpatient services | 0.06 |

| Scahill, Sukhodolsky, Bearss, Findley, Hamrin, Carroll, & Rains (2006) | Disruptive behavior | 24 | 8.9 | 75 | Behavioral Parent Training (Defiant Children) | Usual outpatient services | 0.24 |

| Scherer, Brondino, Henggeler, Melton, & Hanley (1994) | Delinquency | 55 | 15.1 | 81.8 | Multisystemic Therapy (family preservationversion) | Usual system/agency services | 0.13 |

| Sexton & Turner (2010) | Delinquency | 916 | 15.75 | 79 | Functional Family Therapy | Usual ystem/agency services | 0.00 |

| Southam-Gerow, Weisz, Chu, Mcleod, Gordis, & Connor-Smith (2010) | Anxiety | 37 | 10.9 | 43.8 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Coping Cat) | Usual outpatient services | -0.33 |

| Spence & Marzillier (1981) | Delinquency with deficits in interpersonal skills | 56 | 13 | 100 | Social Skills Training and usual care | Usual residential services | -0.27 |

| Stevens & Pihl (1982) | Anxiety, low self esteem, and at-risk for failure | 32 | 12.5 | 64.6 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | Usual outpatient | 0.00 |

| Sukhodolsky, Vitulano, Carroll, Mcguire, Leckman, & Scahill (2009) | Disruptive/oppositional behavior | 26 | 12.7 | 92.31 | Anger Control Training | Usual outpatient services | 0.80 |

| Sundell, Lofholm, Gustle, Hansson, Olsson, & Kadesjo (2008) | Conduct Problems | 156 | 15 | 61 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual outpatient services | -0.10 |

| Szigethy, Kenney, Carpenter, Hardy, Fairclough, Bousvaros, Keljo, Weisz, Beardslee, Noll, & DeMaso (2007) | Depression | 40 | 14.99 | 49 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training) | Usual outpatient services | 0.53 |

| Tang, Jou, Ko, Huang, & Yen (2009) | Depression | 73 | 15.25 | 34.25 | Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents with suicidal risk (IPT-A-IN) | Usual outpatient services | 0.71 |

| Taylor, Schmidt, Pepler, & Hodgins (1998) | Conduct problems | 32 | 5.6 | 74.1 | Behavioral Parent Training (Webster-Stratton's (1992) Parents and Children Videotape Series) | Usual outpatient services | 0.50 |

| Timmons-Mitchell, Bender, Kishna, & Mitchell (2006) | Delinquency: Juvenile justice youth | 93 | 15.1 | 78 | Multisystemic Therapy | Usual system/agency services | 1.30 |

| Van de Weil, Matthys, Cohen-Kettenis & Van Engeland (2003) | Conduct problems | 68 | 10.5 | Not reported | Coping Power Program (Utrecht) | Usual outpatient services | 0.00 |

| van den Hoofdakker, van der Veen-Mulders, Sytema, Emmelkamp, Minderaa, & Nauta (2007); van den Hoofdakker, Nauta, van der Veen-Mulders, Sytema, Emmelkamp, Minderaa, & Hoekstra (2010) | ADHD | 94 | 7.4 | 80.9 | Behavioral Parent Training (Defiant Children, and Helping the Noncompliant Child) | Usual outpatient services | 0.17 |

| Weisz, Southam-Gerow, Gordis, Connor-Smith, Chu, Langer, Mcleod, Jensen-Doss, Updegraff, & Weiss (2009) | Depression | 47 | 11.77 | 44 | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training) | Usual outpatient services | 0.13 |

| Whittington (1982)* | Delinquency | 44 | 16 | 100 | Assertiveness Training and usual care | Usual residential services | 0.27 |

| Young, Mufson, & Gallop (2010) | Depression | 56 | 14.51 | 40.3 | Interpersonal Psychotherapy-adolescent skills training | Usual outpatient services | 0.30 |

| Young, Mufson, & Davies (2006) | Depression | 40 | 13.4 | 14.6 | Interpersonal Psychotherapy-adolescent skills training | Usual outpatient services | 1.23 |

Sample size reflects the number of subjects used to compute effect sizes at post-treatment.

Model-based mean effect size estimates

Indicates dissertations

Note. Usual outpatient services included various individual, group, and family-focused interventions in outpatient clinical programs; usual residential services included various individual and group-focused interventions in youth inpatient, detention, group home and other residential facilities; usual system/agency services included various individual, group, and family-focused interventions arranged through probation and child welfare agencies.

Power

Given the novelty and complexity of the applied three-level meta-analytic approach, a priori power calculation remains an understudied area. So, we used Borenstein et al.20 procedures for standard meta-analysis for an approximate a priori estimate of power. Assuming a high level of between-study variance, a statistical power of 0.80, and alpha of 0.05, at least 32 studies with mean N of 25 participants would be needed to detect a small overall effect size, d=0.20.

Difference between EBP and Usual Care

Our three-level model without moderators focused on the overall EBP versus usual care difference across the 341 dependent ESs retrieved from the 52 studies. Mean ES (d) was 0.29 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.19 to 0.38). t(47.7) = 5.95, p < 0.001. ESs differed significantly between studies ( , χ2(1) = 112.2, p < 0.001); differences between dependent ESs within studies were marginally significant ( , 1.10, χ2(1) = 3.5, p = 0.061). About 45% of the total variance was attributable to differences between studies, about 5% to differences between ESs within studies. To assess the impact of larger, more modern-day trials on the overall mean ES, we calculated the mean of the ES values for the ten studies in the most recent decade with samples larger than 100; taking into account the multilevel structure of the data, their mean ES was 0.14 (95% CI 0.02; 0.26). This did not suggest that more of the larger modern trials would have increased the overall mean ES. Table 1 shows mean ES for each of the 52 studies.

Moderator Analyses

Given the heterogeneity of ESs, moderator analyses were first conducted for each moderator separately to identify characteristics that might explain these differences; moderators found to be significant (p < .05) were then examined simultaneously to address confounding. Results of the first step, presented in Table 2, are summarized here.

Table 2. Results of Moderator Analyses based on Three-level Mixed Effects Models with 341 Dependent Effect Sizes from 52 Studies.

| Moderator | Number of studies | Number of Effect Sizes | Estimate | 95% CI | Test Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | t(109) = 0.10 | 0.920 | ||||

| Post | 49 | 241 | 0.28 | 0.19 to 0.38 | ||

| Follow-up | 22 | 100 | 0.29 | 0.18 to 0.40 | ||

| Post treatment lag time (weeks) | 39 | 257 | -0.00 | -0.00 to 0.00 | t(83.7) = -0.32 | 0.750 |

| Study year | 52 | 341 | 0.00 | -0.01 to 0.01 | t(51.5) = 0.51 | 0.612 |

| Location | t(44.9) = -2.23 | 0.031 | ||||

| North America | 42 | 288 | 0.33 | 0.23 to 0.43 | ||

| Outside North America | 9 | 49 | 0.06 | -0.15 to 0.27 | ||

| Recruitment | F(2,44.9) = 1.85 | 0.168 | ||||

| Recruited | 10 | 77 | 0.41 | 0.20 to 0.62 | ||

| Referred | 19 | 140 | 0.17 | -0.02 to 0.32 | ||

| Non-voluntary | 22 | 119 | 0.31 | 0.17 to 0.45 | ||

| Same vs. different treatment setting | t(34.9)=0.67 | 0.506 | ||||

| EBP same as Usual Care | 32 | 207 | 0.25 | 0.13 to 0.36 | ||

| EBP different from Usual Care | 2 | 14 | 0.43 | -0.08 to 0.93 | ||

| Ethnicity | t(31.1) = -1.38 | 0.176 | ||||

| Majority sample | 22 | 134 | 0.42 | 0.28 to 0.57 | ||

| Minority sample | 15 | 116 | 0.27 | 0.10 to 0.43 | ||

| Percentage male | 50 | 326 | -.00 | -0.01 to 0.00 | t(44.8) = -0.46 | 0.650 |

| Developmental period | t(46.6) = 1.73 | 0.091 | ||||

| Childhood | 15 | 123 | 0.16 | -0.01 to 0.33 | ||

| Adolescence | 37 | 218 | 0.34 | 0.23 to 0.45 | ||

| Target problem | F(2,47) = 1.86 | 0.167 | ||||

| Externalizing | 34 | 202 | 0.31 | 0.20 to 0.43 | ||

| Internalizing | 14 | 123 | 0.30 | 0.13 to 0.48 | ||

| Mixed | 4 | 16 | -0.05 | -0.39 to 0.30 | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| All participants | 10 | 78 | 0.09 | -0.08 to 0.27 | t(14.2) = 2.69 | 0.017 |

| Some or no participants | 9 | 82 | 0.45 | 0.26 to 0.65 | ||

| Informant | F(3,228) = 4.18 | 0.007 | ||||

| Youth | 31 | 117 | 0.30 | 0.19 to 0.40 | ||

| Parent | 22 | 79 | 0.24 | 0.12 to 0.36 | ||

| Teacher | 9 | 21 | 0.10 | -0.10 to 0.29 | ||

| Therapist | 3 | 15 | -0.12 | -0.37 to 0.12 | ||

| EBP treatment | F(3, 96.5) = 1.10 | 0.352 | ||||

| Youth-focused learning-based | 21 | 127 | 0.31 | 0.16 to 0.44 | ||

| Parent- or family-focused | 13 | 81 | 0.16 | -0.01 to 0.33 | ||

| Multi-system approaches | 16 | 99 | 0.35 | 0.19 to 0.52 | ||

| Combinations | 4 | 34 | 0.29 | 0.06 to 0.52 | ||

| Usual Care treatment | F(2, 43.2) = 0.31 | 0.733 | ||||

| Usual outpatient services | 30 | 189 | 0.28 | 0.15 to 0.40 | ||

| Usual residential services | 11 | 68 | 0.26 | 0.04 to 0.48 | ||

| Usual system/agency services | 9 | 79 | 0.37 | 0.15 to 0.59 | ||

| Treatment dosage: EBP vs. Usual Care | F(2,24.5)=-3.29 | 0.054 | ||||

| EBP > Usual Care | 11 | 94 | 0.45 | 0.23 to 0.67 | ||

| EBP = Usual Care | 4 | 15 | 0.22 | -0.18 to 0.62 | ||

| EBP < Usual Care | 8 | 51 | 0.05 | -0.21 to 0.30 | ||

| Investigator Allegiance to EBP | t(93.9)=-1.28 | 0.203 | ||||

| Yes | 35 | 240 | 0.32 | 0.21 to 0.43 | ||

| No | 19 | 101 | 0.21 | 0.07 to 0.36 |

Assessment timing

Testing whether ES is smaller at follow-up than at post-treatment can shed light on the holding power of treatment effects. We found almost identical mean ESs for immediate post-therapy assessments and follow-up assessments averaging 30.92 weeks later (SD=18.74). Number of weeks between post-therapy and follow-up was also not significantly associated with ES. In the 19 studies that included both post-therapy and follow-up assessments, there was also no significant effect of assessment time (t(51.8)=0.20, p=0.840) or number of weeks since the end of therapy (t(67.4)= -0.19, p=0.854). In summary, we found no evidence that effects were significantly weakened over time after treatment.

Study timing

ES was not related to study year (p=0.612), and we did not find significant interactions of study year with target problem (p=0.672), type of EBP treatment (p=0.647), or developmental period (p=0.512). The effect of study year was also not significant within any specific category of these moderators (e.g., externalizing target problems; all p-values > 0.297).

Study geographic location

We tested whether mean ESs differed according to the region in which studies were conducted. Leading EBP researchers6 have argued that EBPs are evidence-based for particular groups and settings, not universally. Because most EBPs were originally developed and tested in North America, they may not fare as well when moved to other contexts. Nine studies (n=42) were conducted outside North America (six in Europe, two in Australia, one in Asia). Location showed a significant moderating effect, with lower ES for studies outside North America. Adding this moderator explained 10% of the between-study variance. One possible explanation for this moderator effect might have been that the efficacy of EBP alone, or usual care alone, differed across countries. However, follow up logistic regression models based on a logit link function showed no location effect on pre-to-post therapy gain (0= no gain; 1= gain) for usual care (t(145) = -0.10, p = 0.923) or EBP (t(145)= -0.05, p = 0.960).

Sample recruitment/referral

We compared mean ES for studies involving participants who were recruited (e.g., through ads) vs. clinically referred vs. incarcerated. The groups did not differ significantly in mean ES. Interestingly, the mean ES for referred youths was modest (d=.17) and not statistically significant.

Treatment setting

We found no significant mean ES difference between studies in which EBP and UC treatment took place in the same vs. different settings.

Ethnicity

Was the EBP vs. usual care difference smaller in ethnic minority samples than majority samples, given that the EBPs were generally not originally designed for minority youths?10 Mean ES was somewhat lower for minority than majority samples, but not significantly so.

Gender distribution

To explore whether gender composition might moderate treatment effects, we tested whether mean ESs was significantly associated with percentage of males in study samples. It was not.

Developmental period

We tested whether EBPs might be more effective with adolescents than children, as suggested by others.110 Mean ES was more than twice as large for studies with adolescents (mean sample age ≥ 12 years; =d=.34) than studies with children (d=.16),but there was no significant moderator effect. Notably, mean ES for children was not statistically significant.

Target problem

We tested whether ES differed according to the form of youth mental health dysfunction--internalizing, externalizing, mixed. The omnibus test was not significant.

Diagnosis

Leaders in the field111 have suggested that EBP effects may be diminished in samples with more severe psychopathology. Indeed, the mean ES for studies that included only youths severe enough to meet DSM criteria was significantly lower than mean ES for studies not requiring a diagnosis, and the mean ES for diagnosed samples was nonsignificant. Adding this moderator explained 30% of the between-study variance.

Informant

Some researchers have found that youths, parents, and other informants differ in their reports of youth improvement following treatment.112,113 In our omnibus test, mean ES differed significantly by informant. Follow-up contrasts revealed larger mean ES for youth-report than teacher-report (t(228) = 2.00, p = 0.047) and therapist-report (t(228) = 3.46, p = 0.001). Mean ES was also larger for parent-report than therapist-report (t(228) = 2.88, p = 0.004). Adding the informant moderator explained 27% of the between-study variance and 100% of the within-study variance.

Type of EBP

Mean ES for parent/family-based treatments was somewhat lower than mean ES for youth-focused learning-based, multi-system, or combined treatments, but the difference was not significant.

Type of usual care

Mean ES was somewhat higher for usual system/agency services than for usual outpatient services and usual residential services; however, the difference among these usual care treatments was not significant.

Treatment dosage

Mean ES was highest (d=0.45) when treatment dose was higher for the EBP than the usual care condition, dropped markedly when dose was the same (d=0.22), and still more when dose was lower for EBP (d=0.05); mean ES was not significant in the latter two conditions. The pattern suggested that EBP superiority might be partially an artifact of larger treatment dose, but the omnibus test was only marginally significant. The dose × type of EBP interaction was also not significant (p=0.266). Note that dose was not consistently reported, and could only be coded in 23 of the 52 studies.

Investigator allegiance

Following several researchers in the field,15 we coded whether study authors had a likely allegiance to the EBP being tested, based on whether or not the EBP developer was an author of the article or a committee member for the dissertation. Although mean ES appeared somewhat larger when investigator allegiance was evident (d=.32 vs. .21; both mean ESs were significant), the difference between them was not significant

Addressing Confounding among Moderators

Although moderators are the keys to explaining ES differences, moderators may not only be associated with ESs but also with each other, complicating the interpretation of single moderator effects. To address this issue, we simultaneously included all three moderators that had shown significant effects, within a three-level mixed effects model to test the effect of each moderator holding the others constant. We also used a parsimonious modeling approach to test for interactions between moderators, adding possible interactions one at a time. Because results of the moderator analysis for the informant variable revealed similar mean ESs for youth and parent reports, and for teacher and therapist reports, these pairs of categories were collapsed into youth or parent reports versus teacher or therapist reports to increase power. Missingness was also coded to reduce loss of information when modeling multiple moderators.

Mean ES for the base category—EBP vs. usual care comparisons reported by youths or parents from studies conducted in North America not requiring a diagnosis—was d=0.43 (95% CI: 0.21 to 0.66), t(43.2) = 3.71, p < 0.001. The mean ESs decreased significantly when teachers or therapists were the informants, d=0.22, t(331) = - 2.29, p=0.023, and nonsignificantly when studies were conducted outside North America, d=0.25, t(44.6) = - 1.42, p=0.161, and when all participants received a formal diagnosis, d=0.17, t(42.7) = - 1.60, p=0.117. We also found a significant study location × informant interaction, F(2,232) = 5.63, p=0.004: in North American studies, EBPs outperformed usual care for youth or parent reports (d=0.30), but not for teacher or therapist reports (d=-0.11). For studies outside North America the opposite held, with EBPs outperforming usual care on teacher or therapist reports (d=0.17), but not on youth or parent reports (d=- 0.19). The non-North American study samples all met formal diagnostic criteria, which might partially explain their lower mean ESs, but the study location × diagnosis interaction was not significant, t(42.3) = 0.09, p=0.929.

Discussion

Our findings support the perspectives of both EBP proponents and critics. In support of the proponents who argue that EBPs should replace usual care, we did find that EBPs produced better outcomes than usual care. The mean standardized difference of .29 was not only significant, but rather durable as well. Effects at follow-up assessments, averaging 31 weeks after treatment ended, were very similar to effects at immediate post-treatment, suggesting that the benefit of EBPs relative to usual care may last well beyond the end of treatment.

That said, the mean ES of d=.29 was modest, somewhat above Cohen's32 threshold for a small effect and reflecting a probability of only 58% that a randomly selected youth receiving EBP would be better off after treatment than a randomly selected youth receiving usual care.114 These finding suggest that (a) the youth EBPs that have been tested to date may be less potent than some have assumed, when pitted against active usual care treatments, and (b) some forms of usual care may be more potent than some have assumed. Indeed, a review of Table 1 reveals several instances in which certain forms of usual care actually outperformed EBPs. Moreover, the effects of EBPs varied widely, even the effects of the same EBP when tested in relation to different forms of usual care (see, e.g., the variation for Multisystemic Therapy in Table 1). These variations in effect size may also relate to trial design: studies using tightly-controlled efficacy designs might be expected to produce somewhat larger effects than studies using effectiveness designs in which EBPs are evaluated under more usual clinical practice conditions.

Our findings appear to support some of the concerns raised by critics of EBPs9-13 and noted in the introduction. The concern that EBPs have been tested mostly with subclinical youths and might not fare well with the more serious, complex, diagnosed youths seen in real-world treatment settings was supported by the low and nonsignificant ES values we found for studies using exclusively diagnosed samples (d=0.09) and studies focused on clinically referred youths (d=0.17). It might also be argued that more severe cases may need medication, alone or in combination with psychotherapy. The concern that EBPs may not generalize well beyond their culture of origin was supported by our finding that EBPs, which looked relatively strong within studies in North America, where most EBPs were developed (d=0.33), showed a much-diminished and nonsignificant effect in studies from other countries (d=0.06). This finding suggests the potential value of cultural adaptation of treatments.115 A third concern noted in the introduction—i.e., that EBPs are too rigidly manualized to permit the personalization that professionals can do in usual care, was not directly testable here, but the recent success of modular strategies for personalizing EBPs (e.g., Weisz and colleagues116) suggests that this possibility bears study in the future. One further concern was raised by our finding that EBP effects that were significant for outcomes reported by the youths (d=0.30) and parents (d=0.24) who participated in therapy became nonsignificant for outcomes reported by teachers (d=0.10), who were more likely to be blind to treatment condition. These caveats may warrant attention by those considering the costs of implementing EBPs (see introduction) relative to the benefits.

Limitations of this meta-analysis suggest future directions. First, usual care interventions were not described in detail in most of the studies, making it difficult to characterize them precisely. The fact that some studies showed usual care matching or outperformed EBPs suggests that those usual care interventions may deserve further study in their own right. Second, additional research in the years ahead will generate more EBP versus usual care comparisons, increasing power to detect additional moderators, and interactions among them (e.g., a properly powered test of whether the informant effect differs by target problem). Third, an interesting feature in research of this type is that EBP versus usual care studies tend to be done in programs, settings, and contexts where research is valued, or at least allowed. It is possible that this affects the meaning of findings in ways that are understood poorly at present, and that findings might be different in clinical settings where research has low priority. Fourth, a growing body of research focuses on pharmacotherapy and its impact in relation to, and in combination with, youth psychotherapy; that research, not included here, could be a useful topic in its own right, for future meta-analyses. Finally, usual care is variable across studies and settings, and in some instances could include some elements of empirically tested treatments, thus reducing the difference between EBPs and usual care in studies like those reviewed here. This further highlights the need for investigators to document thoroughly the contents of the usual care interventions they study.

Our findings showing the modest advantage afforded by current EBPs, and the limits of that advantage (e.g., for diagnosed youths and those outside North America), could be seen as a reality check for clinical scientists who develop evidence-based youth psychotherapies. The findings suggest a need, in the years ahead, both to strengthen and to broaden the benefit afforded by these treatments for youths and families who seek help. At a more fine-grained level, the accumulation of research in the future should make it increasingly possible to identify specific EBPs that do and do not reliably outperform common forms of usual care. Findings at this level of specificity may be valuable to clinicians, clinical directors, and policy-makers, helping to inform their decisions as to which evidence-based psychotherapies offer sufficiently robust gains over usual care to justify the effort and expense of implementing them in practice.

Acknowledgments

Data: Drs. Weisz, Kuppens, and Eckshtain had full access to all of the data in the meta-analysis and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding/Support: The meta-analysis was supported by the Norlien Foundation (255.313704), and the authors were supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Weisz: MH085963), the Annie E. Casey Foundation (Weisz: 209 0037), and the Research Foundation – Flanders, Belgium (Kuppens).

Role of the Sponsors/funders: The funders/sponsors did not shape the design or conduct of the meta-analysis; did not influence the collection, coding, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and did not influence preparation of the manuscript or require review or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None of the authors reports any conflicts of interest.

Additional Contributions: We thank Jessica Alfano, Natalia Gil, and Louisa Michl for their careful work on study retrieval and data preparation for this meta-analysis, and David Langer for his skilled contributions to preparation and management of the dataset.

References

- 1.Silverman W, Hinshaw SP. Evidence-based treatments for child and adolescent disorders [Special Issue] J Clin Child Adolesc. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisz JR. Psychotherapy for children and adolescents: Evidence-based treatments and case examples. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weisz JR, Kazdin AE. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. 2nd. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.AACAP. Practice Parameters. 2011 http://www.aacap.org/cs/root/member_information/practice_information/practice_parameters/practice_parameters.

- 5.SAMHSA. National Register of Health Service Providers. http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/

- 6.Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psych. 1998;66(1):7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.General S. Report of the Surgeon General's Conference on Children's Mental Health: A national action agenda. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NIH. Blue-print for change: Research on child and adolescent mental health. In: Public Health Service, editor. National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention and Deployment USDoHaHS. Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Addis ME, Waltz J. Implicit and untested assumptions about the role of psychotherapy treatment manuals in evidence-based mental health practice:Commentary. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr. 2002;9(4):421–424. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernal G, Scharró-del-Río MR. Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cult Divers and Ethn Min. 2001;7(4):328–342. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garfield SL. Some problems associated with ‘validated’ forms of psychotherapy. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr. 1996;3(3):218–229. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Havik OE, Van den Bos GR. Limitations of manualized psychotherapy for everyday practice. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr. 1996;3(3):264–267. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westen D, Novotny CM, Thompson-Brenner H. The Empirical Status of Empirically Supported Psychotherapies: Assumptions, Findings, and Reporting in Controlled Clinical Trials. Psychol Bull. 2004a;130(4):631–663. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisz J, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM. Evidence-Based Youth Psychotherapies Versus Usual Clinical Care: A Meta-Analysis of Direct Comparisons. Am Psychol. 2006;61(7):671–689. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spielmans GI, Gatlin ET, McFall JP. The efficacy of evidence-based psychotherapies versus usual care for youths: Controlling confounds in a meta-reanalysis. Psychother Res. 2010;20(2):234–246. doi: 10.1080/10503300903311293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mash EJ, Wolfe DA. Disorders of childhood and adolescence. In: Stricker G, Widiger TA, Weiner IB, editors. Handbook of psychology: Clinical psychology. Vol. 8. Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2003. pp. 27–63. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weisz JR, Weiss B, Alicke MD, Klotz ML. Effectiveness of psychotherapy with children and adolescents: A meta-analysis for clinicians. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55(4):542–549. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weisz JR, Weiss B, Han SS, Granger DA, Morton T. Effects of psychotherapy with children and adolescents revisited: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome studies. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):450–468. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. Front Matter. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipsey M, Wilson D. Practical Meta-Analysis (Applied Social Research Methods) Sage Publications, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazdin AE, Weisz JR. Identifying and developing empirically supported child and adolescent treatments. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(1):19–36. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lonigan CJ, Elbert JC. Empirically supported psychosocial interventions for children [Special issue] J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27(1) doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nathan PE, Gorman JM. A guide to treatments that work. New York, NY US: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nathan PE, Gorman JM. A guide to treatments that work. 2nd. New York, NY US: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth A, Fonagy P. What works for whom? A critical review of psychotherapy research. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth A, Fonagy P. What works for whom? A critical review of psychotherapy research. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angold A, Costello EJ, Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Erkanli A. Impaired but undiagnosed. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(2):129–137. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costello EJ, Angold A, Keeler GP. Adolescent outcomes of childhood disorders: The consequences of severity and impairment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(2):121–128. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen AL, Weisz JR. Assessing match and mismatch between practitioner-generated and standardized interview-generated diagnoses for clinic-referred children and adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(1):158–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences: Jacob Cohen. Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedges L, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheung SF, Chan DKS. Dependent Effect Sizes in Meta-Analysis: Incorporating the Degree of Interdependence. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89(5):780–791. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geeraert L, Van den Noortgate W, Grietens H, Onghena P. The Effects of Early Prevention Programs for Families With Young Children At Risk for Physical Child Abuse and Neglect: A Meta-Analysis. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9(3):277–291. doi: 10.1177/1077559504264265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marsh HW, Bornmann L, Mutz R, Daniel HD, O'Mara A. Gender effects in the peer reviews of grant proposals: A comprehensive meta-analysis comparing traditional and multilevel approaches. Rev Educ Res. 2009;79(3):1290–1326. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van den Noortgate W, Onghena P. Multilevel meta-analysis: A comparison with traditional meta-analytical procedures. Educ Psychol Meas. 2003;63(5):765–790. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods (Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences) Sage Publications, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Littell R, Milliken G, Stroup W, Wolfinger R, Schabenberger O. SAS for mixed models. SAS Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Begg CB. Publication bias. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York, NY US: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 399–409. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(3):638–641. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torgerson CJ. Publication Bias: The Achilles' Heel of Systematic Reviews? Brit J Educl Stud. 2006;54(1):89–102. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, Tugwell P. Does the quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 1998;352:609–613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexander JF, Parsons BV. Short-term behavioral intervention with delinquent families: Impact on family process and recidivism. J Abnorm Psychol. 1973;81(3):219–225. doi: 10.1037/h0034537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, LaBorde AP, Rea MM, Murray P, Anderson M, Landon C, Tang L, Wells KB. Effectiveness of a Quality Improvement Intervention for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care Clinics: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA: J Amer Med Assoc. 2005;293(3):311–319. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bank L, Marlowe JH, Reid JB, Patterson GR, Weinrott MR. A comparative evaluation of parent-training interventions for families of chronic delinquents. J Abnorm Child Psych. 1991;19(1):15–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00910562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrington J, Prior M, Richardson M, Allen K. Effectiveness of CBT Versus Standard Treatment for Childhood Anxiety Disorders in a Community Clinic Setting. Behav Change. 2005;22(1):29–43. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borduin CM, Henggeler SW, Blaske DM, Stein RJ. Multisystemic treatment of adolescent sexual offenders. Int J Offender Ther. 1990;34(2):105–113. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borduin CM, Mann BJ, Cone LT, Henggeler SW, Fucci BR, Blaske DM, Williams RA. Multisystemic treatment of serious juvenile offenders: Long-term prevention of criminality and violence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(4):569–578. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borduin CM, Schaeffer CM, Heiblum N. A randomized clinical trial of multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders: effects on youth social ecology and criminal activity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009 Feb;77(1):26–37. doi: 10.1037/a0013035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown TL, Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Multisystemic treatment of substance abusing and dependent juvenile delinquents: Effects on school attendance at posttreatment and 6-month follow-up. Children's Services: Social Policy, Research, & Practice. 1999;2(2):81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chamberlain P, Leve LD, DeGarmo DS. Multidimensional treatment foster care for girls in the juvenile justice system: 2-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(1):187–193. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Comparison of two community alternative to incarceration for chronic juvenile offenders. J Consult ClinPsychol. 1998;66(4):624–633. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davidson WS. The diversion of juvenile delinquents: An examination of the processes and relative efficacy of child advocacy and behavioral contracting. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davidson WS, Redner R, Blakely CH, Mitchell CM, Emshoff JG. Diversion of juvenile offenders: An experimental comparison. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55(1):68–75. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deblinger E, Lippman J, Steer R. Sexually abused children suffering posttruamatic stress symptoms: initial treatment outcome findings. Child Maltreatment. 1996;1(4):310–321. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Deblinger E, Steer RA, Lippmann J. Two-year follow-up study of cognitive behavioral therapy for sexually abused children suffering post-traumatic stress symptoms. Child Abuse Neglect. 1999;23(12):1371–1378. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, Diamond GM, Gallop R, Shelef K, Levy S. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(2):122–131. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dirks-Linhorst PA. An evaluation of a family court diversion program for delinquent youth with chronic mental health needs. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eddy JM, Chamberlain P. Family managment and deviant peer association as mediators of the impact of treatment condition on youth antisocial behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(5):857–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eddy JM, Whaley RB, Chamberlain P. The Prevention of Violent Behavior by Chronic and Serious Male Juvenile Offenders: A 2-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial. J Emot Behav Disord. 2004;12(1):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Emshoff JG, Blakely CH. The Diversion of Delinquent Youth: Family Focused Intervention. Child Youth Serv Rev. 1983;5(4) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fleischman MJ. Social learning interventions for aggressive children: From the laboratory to the real world. Behav Ther. 1982;5(2):55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gillham JE, Hamilton J, Freres DR, Patton K, Gallop R. Preventing Depression Among Early Adolescents in the Primary Care Setting: A Randomized Controlled Study of the Penn Resiliency Program. J Abnorm Child Psych: An official publication of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2006;34(2):203–219. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glisson C, Schoenwald SK, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Dukes D, Armstrong KS, Chapman JE. Randomized trial of MST and ARC in a two-level evidence-based treatment implementation strategy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(4):537–550. doi: 10.1037/a0019160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grant JE. A problem solving intervention for aggressive adolescent males: A preliminary investigation. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hawkins JD, Jenson JM, Catalano RF, Wells EA. Effects of a skills training intervention with juvenile delinquents. Res Social Work Prac. 1991;1(2):107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Henggeler SW, Borduin CM, Melton GB, Mann BJ. Effects of multisystemic therapy on drug use and abuse in serious juvenile offenders: A progress report from two outcome studies. Family Dynamics of Addiction Quarterly. 1991;1(3):40–51. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Smith LA. Family preservation using multisystemic therapy: An effective alternative to incarcerating serious juvenile offenders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(6):953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Smith LA, Schoenwald SK. Family preservation using multisystemic treatment: Long-term follow-up to a clinical trial with serious juvenile offenders. J Child Fam Stud. 1993;2(4):283–293. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, Brondino MJ. Multisystemic treatment of substance-abusing and dependent delinquents: outcomes, treatment fidelity, and transportability. Ment Health Serv Res. 1999 Sep;1(3):171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022373813261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, Brondino MJ, Crouch JL. Eliminating (almost) treatment dropout of substance abusing or dependent delinquents through home-based multisystemic therapy. Am J of Psychiat. 1996;153(3):427–428. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huey SJ, Jr, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB, Pickrel SG, Edwards J. Multisystemic Therapy Effects on Attempted Suicide by Youths Presenting Psychiatric Emergencies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(2):183–190. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200402000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jarden HW. A comparison of problem-solving interventions on the functioning of youth with disruptive behavior disorders. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kerr DCR, Leve LD, Chamberlain P. Pregnancy rates among juvenile justice girls in two randomized controlled trials of multidimensional treatment foster care. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(3):588–593. doi: 10.1037/a0015289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Klein NC, Alexander JF, Parsons BV. Impact of family systems intervention on recidivism and sibling delinquency: A model of primary prevention and program evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1977;45(3):469–474. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.45.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leve LD, Chamberlain P. A randomized evaluation of multidimensional treatment foster care: Effects on school attendance and homework completion in juvenile justice girls. Res Social Work Prac. 2007;17(6):657–663. doi: 10.1177/1049731506293971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leve LD, Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Intervention Outcomes for Girls Referred From Juvenile Justice: Effects on Delinquency. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1181–1185. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luk ESL, Staiger P, Mathai J, Field D, Adler R. Comparison of treatments of persistent conduct problems in primary school children: A preliminary evaluation of a modified cognitive-behavioural approach. Aust NZ J Psychiat. 1998;32(3) doi: 10.3109/00048679809065530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Luk ESL, Staiger PK, Mathai J, Wong L, Birleson P, Adler R. Children with persistent conduct problems who dropout of treatment. Eur Child & Adoles Psychiatry. 2001;10(1):28–36. doi: 10.1007/s007870170044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mann BJ, Borduin CM, Henggeler SW, Blaske DM. An investigation of systemic conceptualizations of parent-child coalitions and symptom change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(3):336–344. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McLaughlin CL. Evaluating the effect of an empirically-supported group intervention for students at-risk for depression in a rural school district. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Morris JP. The effectiveness of anger-control training with institutionalized juvenile offenders: The ‘Keep Cool Program’. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ogden T, Hagen KA. Treatment effectiveness of parent management training in Norway: A randomized controlled trial of children with conduct problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(4):607–621. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ogden T, Halliday-Boykins CA. Multisystemic treatment of antisocial adolescents in Norway: Replication of clinical outcomes outside of the US. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2004;9(2):77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2004.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Parsons BV, Alexander JF. Short-term family intervention: A therapy outcome study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1973;41(2):195–201. doi: 10.1037/h0035181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Patterson GR, Chamberlain P, Reid JB. A comparative evaluation of a parent-training program. Behav Ther. 1982;13(5):638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rohde P, Jorgensen JS, Seeley JR, Mace DE. Pilot Evaluation of the Coping Course: A Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention to Enhance Coping Skills in Incarcerated Youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(6):669–676. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121068.29744.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins CA, Henggeler SW, Cunningham PB, Lee TG, Kruesi MJP, Shapiro SB. A Randomized Trial of Multisystemic Therapy With Hawaii's Felix Class Youths. J Emot Behav Disord. 2005;13(1):13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scahill L, Sukhodolsky DG, Bearss K, Findley D, Hamrin V, Carroll DH, Rains AL. Randomized Trial of Parent Management Training in Children With Tic Disorders and Disruptive Behavior. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):650–656. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210080201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Scherer DG, Brondino MJ, Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Hanley JH. Multisystemic Family Preservation Therapy: Preliminary findings from a study of rural and minority serious adolescent offenders. Special Series: Center for Mental Health Services Research Projects. J Emot Behav Disord. 1994;2(4):198–206. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sexton T, Turner CW. The effectiveness of functional family therapy for youth with behavioral problems in a community practice setting. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice. 2011;1(S):3–15. doi: 10.1037/a0019406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Southam-Gerow MA, Weisz JR, Chu BC, McLeod BD, Gordis EB, Connor-Smith JK. Does cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety outperform usual care in community clinics? An initial effectiveness test. J Am Acad Child AdolescPsychiatry. 2010;49(10):1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Spence SH, Marzillier JS. Social skills training with adolescent male offenders: II. Short-term, long-term and generalized effects. Behav Res Ther. 1981;19(4):349–368. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(81)90056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stevens R, Pihl RO. The remediation of the student at-risk for failure. J Clin Psychol. 1982;38(2):298–301. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198204)38:2<298::aid-jclp2270380211>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sukhodolsky DG, Vitulano LA, Carroll DH, McGuire J, Leckman JF, Scahill L. Randomized trial of anger control training for adolescents with Tourette's syndrome and disruptive behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Apr;48(4):413–421. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sundell K, Hansson K, Löfholm CA, Olsson T, Gustle LH, Kadesjö C. The transportability of multisystemic therapy to Sweden: Short-term results from a randomized trial of conduct-disordered youths. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22(4):550–560. doi: 10.1037/a0012790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Szigethy E, Kenney E, Carpenter J, Hardy DM, Fairclough D, Bousvaros A, Keljo D, Weisz J, Beardslee WR, Noll R, DeMaso DR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and subsyndromal depression. J Am Acad Child Adolec Psychiatry. 2007;46(10):1290–1298. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180f6341f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tang TC, Jou SH, Ko CH, Huang SY, Yen CF. Randomized study of school-based intensive interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents with suicidal risk and parasuicide behaviors. Psychiat Clin Neuros. 2009;63(4):463–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Taylor TK, Schmidt F, Pepler D, Hodgins C. A comparison of eclectic treatment with Webster-Stratton's parents and children series in a children's mental health center: A randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther. 1998;29(2) [Google Scholar]

- 102.Timmons-Mitchell J, Bender MB, Kishna MA, Mitchell CC. An Independent Effectiveness Trial of Multisystemic Therapy With Juvenile Justice Youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35(2):227–236. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Van De Wiel NMH, Matthys W, Cohen-Kettenis P, Van Engeland H. Application of the Utrecht Coping Power Program and Care as Usual to Children With Disruptive Behavior Disorders in Outpatient Clinics: A Comparative Study of Cost and Course of Treatment. Behav Ther. 2003;34(4):421–436. [Google Scholar]

- 104.van den Hoofdakker BJ, Nauta MH, van der Veen-Mulders L, Sytema S, Emmelkamp PMG, Minderaa RB, Hoekstra PJ. Behavioral parent training as an adjunct to routine care in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Moderators of treatment response. Journal of Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(3):317–329. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.van den Hoofdakker BJ, van der Veen-Mulders L, Sytema S, Emmelkamp PMG, Minderaa RB, Nauta MH. Effectiveness of behavioral parent training for children with ADHD in routine clinical practice: A randomized controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(10):1263–1271. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3181354bc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Weisz JR, Southam-Gerow MA, Gordis EB, Connor-Smith JK, Chu BC, Langer DA, McLeod BD, Jensen-Doss A, Updegraff A, Weiss B. Cognitive–behavioral therapy versus usual clinical care for youth depression: An initial test of transportability to community clinics and clinicians. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(3):383–396. doi: 10.1037/a0013877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Whittington CK. Assertion training as a short term treatment method with long term incarcerated juvenile delinquents. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Young JF, Mufson L, Davies M. Efficacy of Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training: An indicated preventive intervention for depression. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2006;47(12):1254–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Young JF, Mufson L, Gallop R. Preventing depression: A randomized trial of interpersonal psychotherapy-adolescent skills training. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(5):426–433. doi: 10.1002/da.20664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. Age effects in parent training outcome. Behav Ther. 1992;23(4):719–729. [Google Scholar]

- 111.TADS. Fluoxetine, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, and Their Combination for Adolescents With Depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc. 2004;292(7):807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.De Los Reyes A. Introduction to the special section: More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. J Clinl Child Adolesc Psychol. 2011;40(1):1–9. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Frye A, Ng MY, Lau N, Bearman SK, Ugueto A, Langer DA, Hoagwood KE. Research Network on Youth Mental Health. Youth top problems: Using idiographic, consumer-guided assessment to identify treatment needs and to track change during psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(3):369–380. doi: 10.1037/a0023307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.McGraw KO, Wong SP. A common language effect size statistic. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111(2):361–365. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Benish SG, Quintana S, Wambold BE. Culturally Adapted Psychotherapy and the Legitimacy of Myth: A Direct-Comparison Meta-Analysis. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(3):279–289. doi: 10.1037/a0023626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Achoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman SK, Daleiden EL, Ugueto AM, Ho A, Martin J, Gray J, Alleyne A, Langer DA, Southam-Gerow MA, Gibbons RD. Research Network on Youth Mental Health. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):274–282. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]