Abstract

A novel core-shell microcapsule system is developed in this study to mimic the miniaturized 3D architecture of pre-hatching embryos with an aqueous liquid core of embryonic cells and a hydrogel-shell of zona pellucida. This is done by microfabricating a non-planar microfluidic flow-focusing device that enables one-step generation of microcapsules with an alginate hydrogel shell and an aqueous liquid core of cells from two aqueous fluids. Mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells encapsulated in the liquid core are found to survive well (> 92 %). Moreover, ~ 20 ES cells in the core can proliferate to form a single ES cell aggregate in each microcapsule within 7 days while at least a few hundred cells are usually needed by the commonly used hanging-drop method to form an embryoid body (EB) in each hanging drop. Quantitative RT-PCR analyses show significantly higher expression of pluripotency marker genes in the 3D aggregated ES cells compared to the cells under 2D culture. The aggregated ES cells can be efficiently differentiated into beating cardiomyocytes using a small molecule (cardiogenol C) without complex combination of multiple growth factors. Taken together, the novel 3D microfluidic and pre-hatching embryo-like microcapsule systems are of importance to facilitate in vitro culture of pluripotent stem cells for their ever-increasing use in modern cell-based medicine.

1. Introduction

Pluripotent stem cells such as embryonic stem (ES) and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells hold great potential for tissue regeneration and cell-based therapy because they are capable of both differentiation (into any somatic cells) and self-renewal (to retain pluripotency) under appropriate culture in vitro.1–6 However, the difficulty to culture and produce a large number of cells with high pluripotency and purity in vitro has been one of the major hurdles to overcome before pluripotent stem cells can be widely used for treating diseases.7–9

Pluripotent stem cells have been cultured both on two-dimensional (2D) substrates and in three-dimensional (3D) space. The former is non-physiological and can lead to altered gene and protein expression in cells.10–14 On the other hand, 3D culture has been shown to be important in controlling proliferation and differentiation of pluripotent stem cells.15–21 As they do in their native milieu in a pre-hatching embryo, these cells tend to self-assemble through cell-cell interactions into 3D aggregates up to a few hundred microns under in vitro culture. Therefore, they are desired to be cultured in an aqueous liquid environment with minimal resistance to better maintain their stemness.22–24 Hanging drop, static or stirring suspension culture, and micro-patterned features have been the most commonly used techniques for culturing pluripotent stem cells.14,21,25–30 However, these methods are limited in several aspects including cell damage due to shear stress, limited control of aggregate size and shape, and/or difficulty to scale up for clinical applications for which the capability of mass production of the cells are needed.

To overcome the challenges, microencapsulation of pluripotent stem cells in biocompatible hydrogel matrices for culture is gaining more and more attention recently because it offers several advantages:31–37 First, the miniaturized culture in microcapsules allows efficient transport of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolites to ensure viability of all cells; second, the selective permeability of hydrogel matrix in microcapsules can protect cells from host’s immune response, which may eliminate the need of immunosuppressive drugs and improve transplantation outcome; and lastly, microencapsulation has been shown to promote cell survival post cryopreservation and banking of the cells for future use. Existing methods for cell microencapsulation commonly involve the use of synthetic or natural polymers to form hydrogel such as that of gelatin, agarose, alginate, and poly(ethylene glycol) and its derivatives.37–41 Typically, cells are suspended in solutions of the polymers and microcapsules are generated by emulsification, electrospray, air shear, or the conventional planar microfluidics, followed by polymerization that can be induced by ultra violet (UV), temperature, chemical, physical, and ionic crosslinking.37–41 However, these methods are usually for producing microbeads with a cell-containing, solid-like hydrogel core that leads to the formation of cell aggregates of uncontrollable size and shape.31,34,42,43 To overcome this problem, microcapsule with a liquid core has been produced by liquefying the hydrogel core of alginate microbeads after coating with poly-l-lysine (PLL) or chitosan to promote proliferation and formation of spheroid aggregate with controllable size and shape.31,34,42 However, this approach requires multiple steps of coating and liquefying that are laborious and often harmful to the encapsulated cells.

Although they have been utilized to contribute significantly to the understanding of stem cell biology, all the above-mentioned in vitro culture systems do not completely recapitulate the native milieu of ES cells in a pre-hatching embryo with a round hydrogel shell (the zona pellucida) and an aqueous liquid core containing embryonic cells. A recent study has shown the potential to encapsulate embryonic carcinoma cells in microcapsules with a liquid core and alginate hydrogel shell using microfluidic device, which, however, may not be utilized for encapsulating the stress sensitive pluripotent stem cells because of the necessity of using cytotoxic chemicals such as oleic acid, methyl propanol, and high concentration of glycerol that have direct contact with cells during microencapsulation.44

In this study, we microfabricated a non-planar (3D) microfluidic flow-focusing device to achieve one-step generation of core-shell microcapsules with an alginate hydrogel shell of controllable thickness and an aqueous liquid core of ES cells without using any cytotoxic chemicals or organic solvents. The core-shell architecture of the microcapsules resembles that of a pre-hatching embryo where ES cells reside naturally. Alginate was used to fabricate the microcapsule shell because of its superb biocompatibility and reversible gelation with divalent cations such as Ca2+ under mild conditions that are not harmful to living cells.45,46 Mouse ES cells encapsulated in the liquid core of the microcapsules were found to survive well (> 92%) and proliferate to form a single aggregate in each microcapsule within 7 days. Furthermore, the aggregated cells were found to have significantly higher expression of pluripotency marker genes compared to the ES cells cultured on 2D substrates and they could be efficiently differentiated into beating cardiomyocytes under the induction of a single small molecule (cardiogenol C) without complex combination of multiple growth factors.

2. Experimental

2.1. Fabrication of non-planar microfluidic device

To fabricate polydimethyl siloxane (PDMS, Dow Corning) microfluidic device, silicon master with patterned microfluidic channels was prepared using a multilayer (3-step UV exposure) SU8 fabrication technique.47 Briefly, photosensitive epoxy (SU-8 2025, MicroChem) was spun coated onto a 4-inch silicon wafer. The thickness of the first SU-8 coating was 60 µm. The wafers were then soft-baked at 95 °C for 9 min and exposed to UV light through the first shadow mask printed with the core channel. After a post-exposure baking at 90 °C for 7 min, an additional layer (50 µm) of SU-8 photoresist was spun coated, soft baked, exposed with a different shadow mask to pattern shell channel. The third layer for oil channel was similarly patterned. All three exposures were aligned using an EVG620 automated mask aligner. The SU8 pattern on the substrate was developed in SU-8 developer (MicroChem) for 10 min, rinsed with isopropyl alcohol, and then dried using nitrogen gas. PDMS pre-polymer was then poured on the silicon substrate and cured at 65 °C for 3 h to form PDMS slab. Thereafter, the PDMS slab embedded with microchannels (half-depth) was lifted off. Two PDMS slabs with the same channel design were then plasma-treated for 30 s using Harrick PDC-32 G plasma cleaner at 18 W and 27 Pa, wetted with methanol (to prevented instant bonding), and aligned and bonded together under microscope to produce the final microfluidic device. Assembled device was kept on hotplate at 80 °C for ~ 10 min to evaporate residual methanol and further kept at 65 °C for 2 days to make it sufficiently hydrophobic for experiments.

2.2. Cell culture

R1 mouse ES cells (ATCC) were cultured in medium consisted of Knockout DMEM (Millipore) supplemented with 15 % (v/v) Knockout Serum (Millipore), 4 mM l-glutamine (Sigma), 100 µg ml−1 antibiotics (Invitrogen), 1000 U ml−1 Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) (Millipore), 10 µg ml−1 gentamicin (Sigma), and 0.1 mM mercaptoethanol (Sigma) on a gelatin coated tissue culture flasks at 37 °C in a humidified 5 % CO2 incubator. When reaching 70% confluence, cells were detached using trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen) and gently pipetted to break aggregates. The cells were then centrifuged, re-suspended, and counted for further passaging or experimental use.

2.3. Encapsulation of cells in core-shell microcapsules for miniaturized 3D culture

The fluids in the core and shell microchannels were 1% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (Sigma) and 2% purified sodium alginate (Sigma) in 0.3 M d-mannitol (Sigma) solution, respectively. All the solutions were sterile and buffered with 10 mM HEPES to maintain pH 7.2 before use. To make mineral oil infused with calcium chloride for flowing in the oil channel, stable emulsion of mineral oil and 0.7 g ml−1 calcium chloride solution (volume ratio: 3:1 with the addition of 1.2 % SPAN 80) was prepared by sonication for 1 min using a Branson sonifier. Water in the emulsion was then removed by rotatory evaporation for ~ 2 min at 90 °C. All solutions were injected into the microfluidic device using syringe pump at room temperature to generate microcapsules that were collected in 4 °C medium in 50 ml centrifuge tube. Microcapsules were separated from oil into medium by gently centrifuging at 300 rpm. The microencapsulated cells were cultured in ES cell medium for up to 7 days. Further pluripotency marker and cardiac differentiation analyses were performed using the aggregated cells on day 7. Cell viability was determined using the standard Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity assay kit (Invitrogen).

2.4. Pluripotency analysis

For pluripotency analysis, ES cell aggregates were released from the core-shell microcapsules on day 7 by incubating in 55 mM sodium citrate solution for ~ 5 min. Aggregates were then washed with 1× PBS and centrifuged. For quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis, RNAs were extracted from the aggregated cells using RNeasy plus mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Next, reverse transcription was carried out to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) using the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) and GeneAmp 9700 PCR system. The qRT-PCR was conducted with the superfast SYBR Green mix (Bio-Rad) using a Bio-Rad CFX96 real time PCR system. Relative gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCT method built in the Bio-Rad software. Pluripotency genes including Oct-4, Sox2, Nanog, and Klf2 were studied with GAPDH being used as the housekeeping gene. Primer sequences of GAPDH and the 4 pluripotency genes are given in Table S1. For immunohistochemical staining of two pluripotency marker proteins including Oct-4 and SSEA-1, cell aggregates were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed 3 times with 1× PBS, and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 (Sigma). The aggregates were then incubated in 3% BSA in 1× PBST (1× PBS and 0.05% Tween 20) at room temperature for 1 h to block non-specific binding, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies (Abcam) targeting Oct-4 or SSEA1. The aggregates were then washed 3 times and incubated in dark at room temperature for 45 min with secondary antibodies (Abcam) including DyLight 488 conjugated rabbit IgG for Oct4 or DyLight 550 conjugated mouse IgM for SSEA-1. All the antibodies were diluted in 3% BSA in 1× PBST. The aggregates were then washed and further stained for nuclei using Hoechst for examining with an Olympus FV 1000 confocal microscope.

2.5. Cardiac differentiation analysis

For cardiac differentiation, ES cell aggregates were released from the core-shell microcapsules on day 7 by incubating in 55 mM sodium citrate solution for ~ 5 min. Released aggregates were transferred into gelatin coated 6-well plates for culturing in differentiation medium consisted of DMEM (Invitrogen), 20 % FBS (Hyclone), 0.25 µM cardiogenol C (Sigma), and 100 µg ml−1 antibiotics for 3 days. Thereafter, the cells were cultured up to day 13 in DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS and 100 µg ml−1 antibiotics. Culture medium was changed every other day. The number of beating foci (see Movie S3) was counted daily from the day of initiating differentiation. On average, more than 100 aggregates per experiment were analyzed to calculate beating percentage. In addition, cardiac differentiation using the conventional method to form embryoid body (EB) in hanging drops was conducted as control. In short, EBs were formed by suspending 1500 single ES cells in 20 µl hanging drop of ES cell culture medium without LIF and cultured for 4 days. The EBs were then plated on gelatin coated 6-well plate for further differentiation in medium containing DMEM, 20% FBS, and 100 µg ml−1 antibiotics with medium changed every other day.

For differentiated marker gene analysis using qRT-PCR, cells were harvested using trypsin/EDTA on day 12 of differentiation, processed using the same procedure described in section 2.4, and analyzed for cardiac and mesodermal differentiation markers including cardiac troponin T (cTnT), Nkx2.5, and Brachyury (or T) genes. Primer sequences for 3 differentiated genes are also provided in Table S1. In addition, immunohistochemical staining and flow cytometry were conducted, for which cells were processed as that described in section 2.4 and treated with primary antibodies (Abcam) targeting cTnT, connexin 43, and α-actinin. Secondary antibodies used were Dylight 488-conjugated rabbit IgG (Abcam) for connexin 43 and α-actinin and rhodamine 555-conjugated mouse IgG (Invitrogen) for cTnT. The aggregates were then washed and further stained with Hoechst for nuclei and examined with an Olympus FV 1000 confocal microscope. Flow cytometry analysis was conducted using a BD LSR II Flow Cytometer. To estimate the percentage of cTnT positive cells, un-stained differentiated cells were used as control to eliminate the background fluorescence. The flow cytometry data were further analyzed using the FlowJo software.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All the experiments were conducted for at least three times independently. Results are reported as Mean ± standard deviation (SD). Two-tailed student t-test was performed to determine statistical significance (p < 0.05).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Non-planar microfluidic flow-focusing device

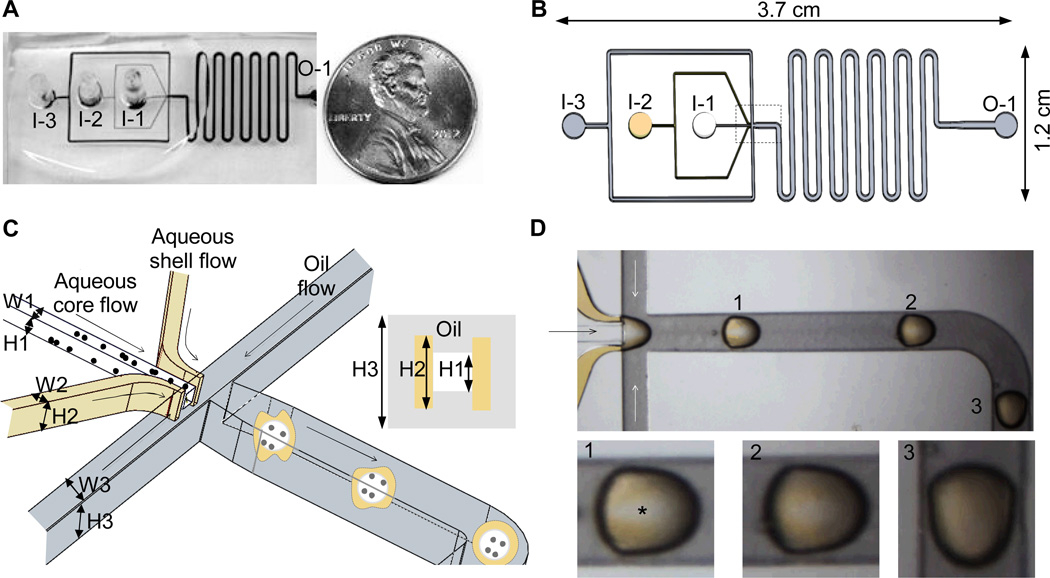

An overview together with a schematic illustration of the 3D design of the non-planar microfluidic device is shown in Fig. 1A–C. The device was made by plasma-bonding two PDMS slabs fabricated with the same channel design (Fig. 1B) to form rectangular core, shell and oil channels with three inlets (I-1, I-2, and I-3 for core, shell, and oil flows, respectively) and one outlet (O-1). At the flow-focusing junction that is indicated by the dashed box in Fig. 1B and further illustrated schematically in Fig. 1C, the height (or depth) and width of the core (H1 × W1), shell (H2 × W2), and oil (H3 × W3) channels are 120 × 120, 220 × 50, and 320 × 200 µm, respectively. As shown in the inset of Fig. 1C, the height (or depth) of core channel (H1: 120 µm) is the smallest, followed by the shell (H2: 220 µm) and oil (H3: 320 µm) channels. After the flow-focusing junction, a serpentine design was used to attain a total channel length of ~ 130 mm for sufficient gelation of alginate in the device.

Figure 1.

Non-planar microfluidic flow-focusing device for one-step generation of core-shell microcapsules from two aqueous fluids: (A), an overview of the microfluidic device with reference to a U.S. quarter coin; (B), a schematic view of the microchannel system: I-1, I-2, and I-3 are the inlets of core, shell, and mineral oil flows, respectively, and O-1 is the outlet; (C), a zoom-in look of the non-planar design at flow-focusing junction (the dashed box region in B); and (D), typical images showing gradual coverage of the core fluid by the shell fluid that was stained yellowish with 0.5% high molecular weight (500 kD) dextran-FITC (a corresponding Movie S1 is given in Electronic Supplementary Information)

3.2. Generation of core-shell microcapsules from two (core and shell) aqueous flows in one step

To generate pre-hatching embryo-like microcapsules with an aqueous hydrogel shell and an aqueous liquid core in one step in the microfluidic device, 1% cellulose solution either with or without ES cells, 2% sodium alginate solution, and mineral oil infused with calcium chloride were injected through the core, shell, and oil channels, respectively. Cellulose and mineral oil were used because of their excellent biocompatibility for cell culture.48–50 At the non-planar flow-focusing junction (Fig. 1C), the shell flow was pushed by the crossing oil flow to fold over the parallel core flow and both the aqueous core and shell flows were sheared by the crossing oil flow into droplets as a result of the immiscible nature (i.e., high surface tension) between water and oil.

Because the two parallel aqueous flows have direct contact, mixing between them must be minimized to retain the core-shell configuration. This was achieved by using 1% cellulose in the core flow to significantly raise its viscosity (alginate in the shell flow was highly viscous already). Moreover, we infused mineral oil (cell culture grade) with calcium chloride that could dissolve and diffuse into the aqueous shell flow to crosslink alginate there into hydrogel before the droplets exited the device. As a result, the core-shell configuration could be stabilized to encapsulate cells for extended culture.

It is worth to note that a non-planar flow-focusing design with varied channel depth (Fig. 1C) is necessary for making core-shell microcapsules from two parallel aqueous flows by allowing the viscous shell flow to fold over and envelope around the viscous core flow. A non-planar channel design is even important for efficient production of core-shell emulsions of immiscible fluids.51 At an oil flow rate of 4 ml h−1, the folding and enveloping of the aqueous shell flow (220 µl h−1, made visible by adding 0.5% 500 kD FITC-dextran to give the yellow appearance) over the aqueous core flow (110 µl h−1) are shown in Fig. 1D (see a corresponding Movie S1) of a top view of the flows in the region of flow focusing, where a white band (indicated by asterisk) of the core flow was clearly seen on droplet 1, diminished on droplet 2, and disappeared on droplet 3. The observation is a result of the gradual displacement of oil on top (and at bottom) of the core flow by the folding-over viscous shell flow, as illustrated schematically in 3D by the droplets in the microchannel after flow focusing in Fig. 1C. The non-spherical appearance of the droplets in Fig. 1D was due to their relatively large size (compared to the microchannel) to block most of the flow in the microchannel, which resulted in high enough pressure difference along the droplets to deform them. Smaller and thus more spherical droplets were produced under the same flow rates when there was no dextran in the core flow (lower viscosity), as shown in Movie S2.

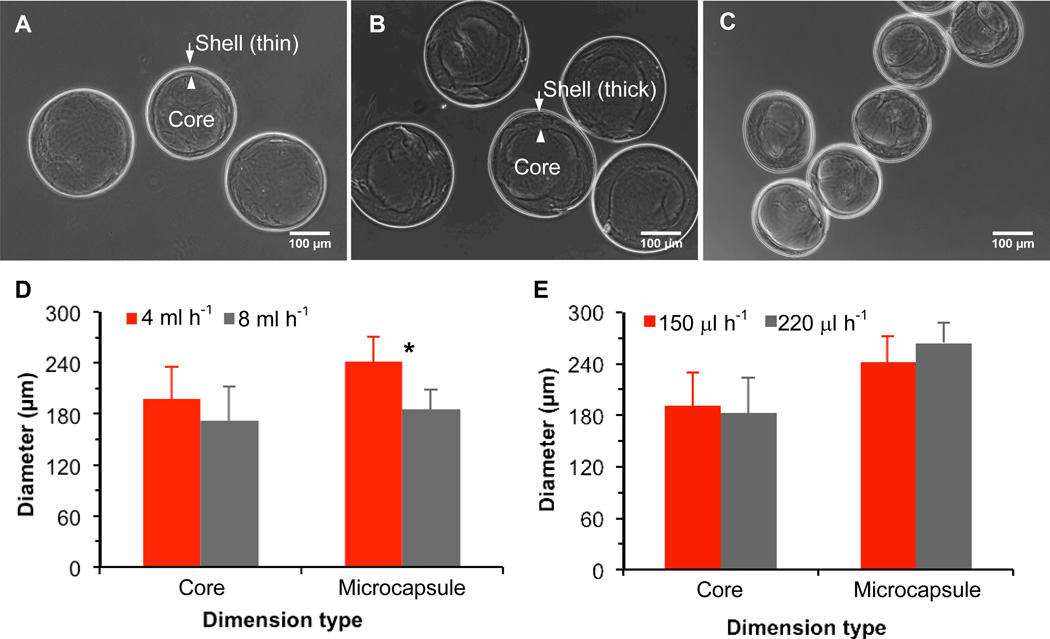

Moreover, a spherical core-shell architecture is clearly observable in phase contrast images of the microcapsules after exiting the device (Fig. 2A–C), which suggests the highly elastic nature of the alginate hydrogel in the microcapsule shell that enables the microcapsules to take a spherical shape (driven by minimization of surface tension) after exiting the microchannel when the pressure difference across them is gone. The inner boundary of the shell does not appear as smooth as the outer boundary, which is not surprising because the interfacial surface tension between the two aqueous flows on the inner boundary is negligible compared to that between the aqueous shell and oil flows on the outer boundary. In addition, the shell thickness and microcapsule size can be easily varied by adjusting the flow rates of the three (core, shell, and oil) flows as shown in Fig. 2A (core: 110 µl h−1, shell: 150 µl h−1, and oil: 4 ml h−1), B (core: 110 µl h−1, shell: 220 µl h−1 and oil: 4 ml h−1), and C (core: 110 µl h−1, shell: 150 µl h−1, and oil: 8 ml h−1). The microcapsules in Fig. 2A and C are ~ 240 µm and 190 µm on average, respectively, with a wall thickness of ~ 10 µm while in Fig. 2B, they are ~ 260 µm on average with a wall thickness of ~ 50 µm. The data under the various flow conditions are further shown in Fig. 2D and E to illustrate the effect of the three flow rates on the core and overall microcapsule size (diameter). Clearly, the core size is mainly determined by the core flow rate and is not significantly affected by the change in shell (from 150 to 220 µl h−1) and oil (from 4 to 8 ml h−1) flow rates. The overall microcapsule size is significantly decreased with the increase in oil flow rate, but it is not significantly affected by the change in shell flow rate. Lastly, it is worth to note that the non-planar microfluidic device could be easily utilized to produce microcapsules with a collagen (and potentially many other biomaterials) core and an alginate hydrogel shell, as shown in Fig. S1.

Figure 2.

Typical phase contrast images of microcapsules of (A), ~ 240 µm with a thin (~ 10 µm) shell; (B); ~ 260 µm with a thicker (~ 50 µm) shell; and (C), ~ 190 µm with a thin (~ 10 µm) shell together with quantitative data showing the effect of (D) oil and (E) shell flow rates on the core and overall microcapsule size. The size of the irregular core was calculated as the equivalent diameter of a circle with the same area as the core. The core and shell flow rates were 110 and 150 µl h−1, respectively for obtaining the data shown (D) and the core and oil flow rates were 110 µl h−1 and 4 ml h−1, respectively for obtaining the date shown in (E). *: Statistically significant (p < 0.05)

3.3. Encapsulation of ES cells cultured in pre-hatching embryo-like microcapsules

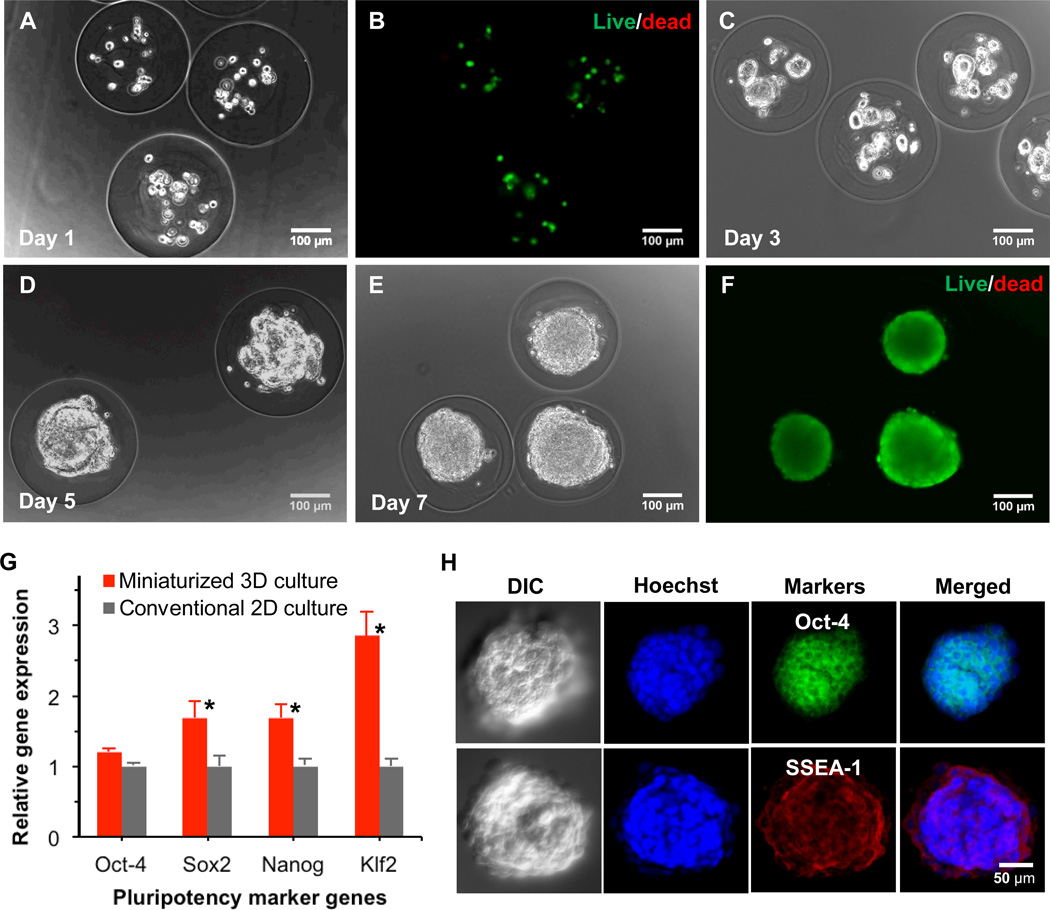

All ES cell encapsulation experiments were conducted using the same flow rates as that used for generating microcapsules shown in Fig. 2B. Concentration of ES cells in core solution was 5 million cells/ml. Typical phase contrast and fluorescence images of ES cells immediately after encapsulation showing high viability (> 92%) are given in Fig. 3A and B, respectively. A total of 20 ± 6 cells were successfully encapsulated in the aqueous liquid core of each microcapsule. The high cell viability is attributed in part to the use of biocompatible mineral oil and cellulose.48–50 Also, the gelation of alginate in the shell shortly after contacting calcium infused in oil should improve cell viability by confining cells in the aqueous core so that they are not exposed to oil and the damaging shearing stress near the interface between the aqueous shell and oil flows.

Figure 3.

Viability, proliferation, and pluripotency of ES cells encapsulated in the pre-hatching embryo-like core-shell microcapsules: (A), typical phase contrast image showing ~ 20 ES cells encapsulated in each microcapsule immediately after microencapsulation; (B), the corresponding fluorescence image showing high viability (green) of the encapsulated ES cells immediately after microencapsulation; (C), (D), and (E) are phase contrast images of the encapsulated cells on day 3, 5, and 7, respectively, showing proliferation of the encapsulated ES cells to form a single aggregate in each microcapsule on day 5–7; (F), typical fluorescence image of the ES cell aggregates in the microcapsule on day 7 showing high viability of the aggregated cells; (G), qRT-PCR data showing significantly higher expression of pluripotency marker genes including Sox2, Nanog, and Klf2 in the aggregated ES cells formed under miniaturized 3D culture in the core-shell microcapsules compared to ES cells cultured on 2D surface; and (H), immunohistochemical staining of pluripotent marker proteins including Oct-4 (green) and SSEA-1 (red) in the ES cell aggregates together with Hoechst (blue) staining of cell nuclei and differential interference contrast (DIC) images showing the aggregate morphology. *: Statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Phase contrast images of the encapsulated ES cells at day 3, 5, and 7 demonstrating their proliferation are given in Fig. 3C, D, and E, respectively. The cells were observed to form multiple small aggregates within 3 days that further merged to form a single aggregate in each microcapsule on day 5–7, depending on the number of cells initially encapsulated in the core. The aggregates were 163 ± 29 µm, which was similar to the diameter of the liquid core in the microcapsules. High viability of cells in the aggregates is clearly seen in Fig. 3F where no dead cell (red stain) is observable at all. Therefore, using this non-planar microfluidic encapsulation technology, it is possible to form ES cell aggregates of high cell viability and fairly uniform size (see Fig. S2 of a low power micrograph showing many microcapsules and cell aggregates).

The proliferation of ES cells in the core-shell microcapsule mimics that of embryonic cells (including ES cells) during early (pre-hatching) embryo development from a few cells to a few tens of cells and later a single merged cell aggregate (i.e., blastocyst) in the hydrogel shell of each pre-hatching embryo (i.e., zona pellucida), which should promote self-renewal of the ES cells. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 3G, further quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) studies of the expression of four pluripotency genes (Oct-4, Sox2, Nanog, and Klf2) show significantly higher expression of 3 (Sox2, Nanog, and Klf2, p < 0.05) out of the 4 genes in the aggregated ES cells from miniaturized 3D culture, compared to the cells grown on 2D surface. All the 4 genes are key transcription factors involved in maintaining stemness or self-renewal of pluripotent stem cells.1–6 To further examine the pluripotency at the protein expression level, immunohistochemical staining was performed for two pluripotency marker proteins: Oct-4 and SSEA-1. As shown in Fig. 3H, both ES cell specific marker proteins are highly expressed within the aggregated ES cells.

These results demonstrate that the miniaturized 3D culture can maintain both high viability and high pluripotency of the encapsulated ES cells. This may be due to efficient transport of oxygen, nutrients, and metabolic wastes in the miniaturized liquid core of the pre-hatching embryo-like microcapsule, which allows better survival and proliferation of all encapsulated cells.31–37 Moreover, the alginate shell can force the encapsulated cells to stay together and may prevent the dilution into bulk medium of endogenous metabolites produced by the encapsulated ES cells to maintain their pluripotency. All these should render the miniaturized 3D culture to better recapitulate the native milieu of ES cells in pre-hatching embryos compared to the open 2D or even bulk 3D culture.22–24

3.4. Cardiac differentiation of aggregated ES cells

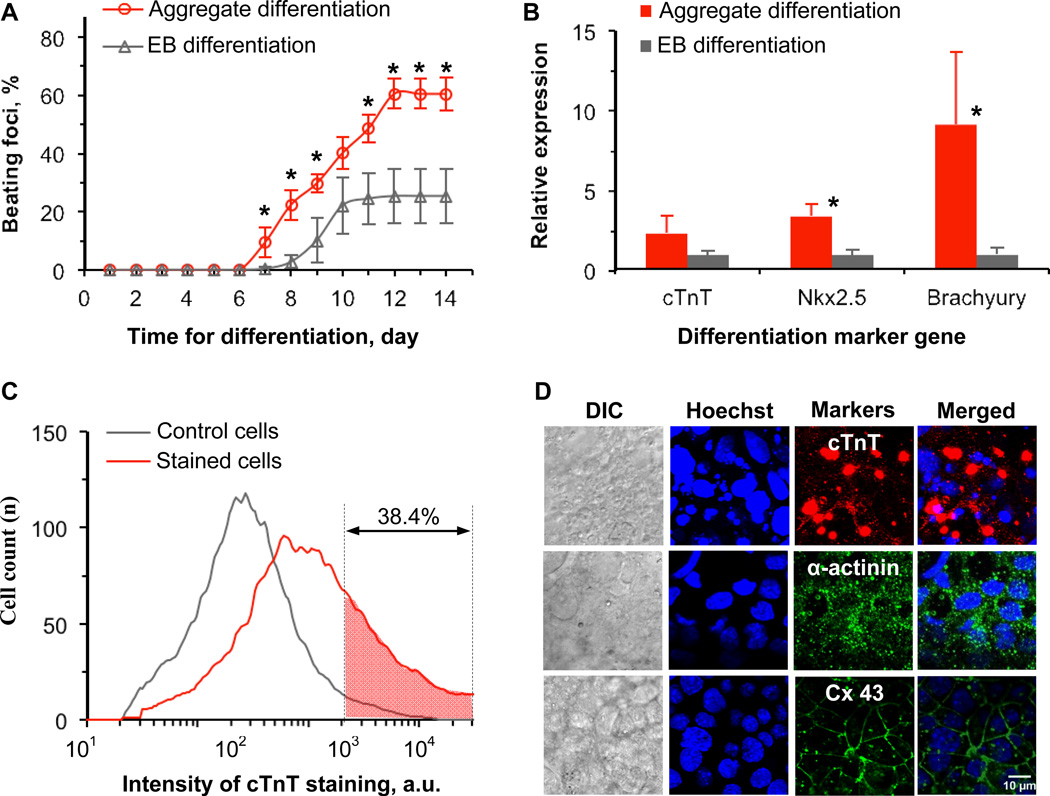

To further ascertain their stemness, we performed cardiac differentiation using cardiogenol C as the single inducer on the ES cell aggregates formed on day 7 (aggregate differentiation). Cardiogenol C is a small molecule (296.75 D) that has been reported to be promising for inducing cardiogenic differentiation of both pluripotent and multipotent stem cells.52–54 As control, we also performed cardiac differentiation using the conventional method with embryoid body (EB) obtained in hanging drops (EB differentiation). As shown in Fig. 4A, spontaneously beating foci were first observed on day 7 for the aggregate differentiation while it was not observed until day 8 for EB differentiation. The cumulative percentage of beating foci reached the maximum (60.4 ± 5.1%) on day 12 for the aggregate differentiation and was significantly higher than that for EB differentiation. The maximum cumulative percentage of beating foci for EB differentiation was 25.3 ± 9.3%, which is comparable to what has been reported previously.55 A typical bright field image of the differentiated cells from the aggregate differentiation on day 12 is shown in Fig. S3 (the boundary of a spontaneously beating focus is labeled with dashed line) and the corresponding animation is given as Movie S3.

Figure 4.

Cardiac differentiation using the 3D aggregated ES cells and the conventional embryoid body (EB) method: (A), cumulative percentage of beating foci as a function of time after initiating cardiac differentiation; (B), qRT-PCR data showing expression of markers of cardiomyocytes (cTnT), cardiac progenitor cell marker (Nkx2.5), and mesodermal cell marker (Brachyury or T) in the differentiated cells; (C), flow cytometry data of unstained control cells and cTnT stained cells showing expression of cardiomyocyte specific marker (cTnT) protein in ~ 38% of the cells differentiated from the 3D aggregated ES cells on day 12 of differentiation; and (D), immunohistochemical staining for cardiomyocyte specific marker proteins including cTnT (red), α-actinin (green), and connexin 43 (Cx 43, green) in the cells differentiated from the 3D aggregated ES cells on day 12 after initiating differentiation together with Hoechst (blue) staining of cell nuclei and differential interference contrast (DIC) images showing the aggregate morphology, demonstrating high expression of all the differentiated marker proteins. *: Statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Further qRT-PCR analyses (Fig. 4B) show significantly higher expression of early mesoderm marker gene brachyury or T (~ 9 folds) and cardiac progenitor marker gene Nkx2.5 (~ 3.4 folds) in the cells from aggregate differentiation compared to that from EB differentiation. The expression of cardiac troponin T (cTnT), a marker gene specific of cardiomyocytes, is also higher (although less significant, p = 0.11) for aggregate differentiation than EB differentiation. In addition, the differentiated cells from aggregate differentiation show significantly higher levels of brachyury (~ 45 folds) and Nkx2.5 (~ 40 folds) compared to the aggregated ES cells before differentiation and this difference is even much bigger (~ 1200 folds) for cTnT (Fig. S4).

Translation of the cTnT gene to cTnT protein in cardiomyocytes is required for the cells to beat and function. Therefore, further flow cytometry analysis was conducted to quantify intracellular cTnT protein. As shown in Fig. 4C, the cardiomyocyte specific protein was expressed in ~ 38% of the differentiated cells from aggregate differentiation. The expression of cTnT protein in the differentiated cells was further confirmed by immunohistochemical staining (Fig. 4D). Also shown in Fig. 4D are the highly positive staining of α-actinin (a protein in the z line of cardiac sarcomere) that is also important for cardiomyocytes to beat and function and connexin 43 (Cx 43, a protein in the gap junction between cardiomyocytes) that is indispensible for synchronized beating of multiple cardiomyocytes.

These results confirm that ES cell aggregates formed in the pre-hatching embryo-like core-shell microcapsules are indeed capable of being differentiated directly into functional cardiomyocytes. Of note, the result of ~ 38% of cTnT protein positive cells in the differentiated cell population is close to what has been reported in the literature for cardiac differentiation of ES cells.56 Moreover, it is close to that (~ 30% on average) of cardiomyocytes in the heart.57,58 Therefore, the differentiated cell aggregates may closely mimic native cardiac tissue and may be transplanted directly to treat cardiac diseases such as myocardial infarction, which warrants further investigation in future studies.

Considering that thousands of microcapsules can be easily produced using the non-planar microfluidic device in a few minutes and only a few tens of cells are required in each microcapsule to form ES cell aggregate of controllable size within 7 days as a result of the miniaturized 3D culture in the pre-hatching embryo-like microcapsules, the microencapsulation technology developed in this study is superior to the commonly used, labor-intensive hanging-drop method of culturing ES cells. For the latter, at least a few hundred cells in each hanging drop are usually needed in order to form pluripotent stem cell aggregates or embryoid bodies (EBs) in a few days.29,30 In addition, many of the microfluidic channels could be fabricated to run in parallel to further increase the throughput of the technology.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we successfully fabricated a non-planar microfluidic flow-focusing device to generate pre-hatching embryo-like microcapsules with an aqueous liquid core of ES cells and an alginate hydrogel shell with controllable size. The core-shell microcapsule system was shown to be excellent for miniaturized 3D culture of pluripotent stem cells to promote their proliferation and aggregation and to maintain higher pluripotency compared to the conventional 2D culture. Moreover, this microencapsulation technology can be used to easily produce thousands of microcapsules in a matter of minutes, which is highly desirable for the clinical applications of pluripotent stem cells where a large number of cells are usually desired. Therefore, the novel microencapsulation technology and miniaturized 3D culture system developed in this study are of importance to facilitate in vitro culture and expansion of pluripotent stem cells for their ever-increasing use in modern cell-based medicine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by grants from NSF (CBET-1154965) and NIH (R01EB012108). The authors would like to thank Joe Jeffery and Benjamin Weekes for their technical assistance with experiments.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information Available (Table S1, Figures S1–S4, and Movies S1–S3)

References

- 1.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin, Thomson JA. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Shimamura A, Lensch MW, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K, Daley GQ. Cell. 2008;134:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith LG, Naughton G. Science. 2002;295:1009–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1069210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Science. 1993;260:920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gearhart J. Science. 1998;282:1061–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H, Lin J, Roy K. Biomaterials. 2006;27:5978–5989. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scadden DT. Nature. 2006;441:1075–1079. doi: 10.1038/nature04957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Science. 2001;294:1708–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith LG, Swartz MA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:211–224. doi: 10.1038/nrm1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fluri DA, Tonge PD, Song H, Baptista RP, Shakiba N, Shukla S, Clarke G, Nagy A, Zandstra PW. Nat Methods. 2012;9:509–516. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giobbe GG, Zagallo M, Riello M, Serena E, Masi G, Barzon L, Di Camillo B, Elvassore N. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:3119–3132. doi: 10.1002/bit.24571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang M, Lee ST, Kim JW, Yang JH, Yoon JK, Park JC, Ryoo HM, van der Vlies AJ, Ahn JY, Hubbell JA, Song YS, Lee G, Lim JM. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3571–3580. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Z, Leung M, Hopper R, Ellenbogen R, Zhang M. Biomaterials. 2010;31:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peerani R, Rao BM, Bauwens C, Yin T, Wood GA, Nagy A, Kumacheva E, Zandstra PW. Embo J. 2007;26:4744–4755. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storm MP, Orchard CB, Bone HK, Chaudhuri JB, Welham MJ. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;107:683–695. doi: 10.1002/bit.22850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen JA, Swartz MA. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:1469–1490. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shafa M, Day B, Yamashita A, Meng G, Liu S, Krawetz R, Rancourt DE. Nat Methods. 2012;9:465–466. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su G, Zhao Y, Wei J, Han J, Chen L, Xiao Z, Chen B, Dai J. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3215–3222. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison SJ, Shah NM, Anderson DJ. Cell. 1997;88:287–298. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81867-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watt FM, Hogan BL. Science. 2000;287:1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang WJ, Itaka K, Ohba S, Nishiyama N, Chung UI, Yamasaki Y, Kataoka K. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2705–2715. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faulkner-Jones A, Greenhough S, King JA, Gardner J, Courtney A, Shu WM. Biofabrication. 2013;5 doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/5/1/015013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park J, Cho CH, Parashurama N, Li YW, Berthiaume F, Toner M, Tilles AW, Yarmush ML. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1018–1028. doi: 10.1039/b704739h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bratt-Leal AM, Carpenedo RL, McDevitt TC. Biotechnol Prog. 2009;25:43–51. doi: 10.1002/btpr.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurosawa H. J Biosci Bioeng. 2007;103:389–398. doi: 10.1263/jbb.103.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tung YC, Hsiao AY, Allen SG, Torisawa YS, Ho M, Takayama S. Analyst. 2011;136:473–478. doi: 10.1039/c0an00609b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson JL, McDevitt TC. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2013;110:667–682. doi: 10.1002/bit.24802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velasco D, Tumarkin E, Kumacheva E. Small. 2012;8:1633–1642. doi: 10.1002/smll.201102464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma M, Chiu A, Sahay G, Doloff JC, Dholakia N, Thakrar R, Cohen J, Vegas A, Chen D, Bratlie KM, Dang T, York RL, Hollister-Lock J, Weir GC, Anderson DG. Adv Healthc Mater. 2012 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, Zhao S, Rao W, Snyder J, Choi JK, Wang J, Khan IA, Saleh NB, Mohler PJ, Yu J, Hund TJ, Tang C, He X. J Mater Chem B Mater Biol Med. 2013;2013:1002–1009. doi: 10.1039/C2TB00058J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serra M, Correia C, Malpique R, Brito C, Jensen J, Bjorquist P, Carrondo MJ, Alves PM. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W, Yang G, Zhang A, Xu LX, He X. Biomed Microdevices. 2010;12:89–96. doi: 10.1007/s10544-009-9363-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W, He X. J Healthc Eng. 2011;2:427–446. doi: 10.1260/2040-2295.2.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang KS, Lu K, Yeh CS, Chung SR, Lin CH, Yang CH, Dong YS. J Control Release. 2009;137:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Overhauser J. Methods Mol Biol. 1992;12:129–134. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-229-9:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chayosumrit M, Tuch B, Sidhu K. Biomaterials. 2010;31:505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang W, He X. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:074515. doi: 10.1115/1.3153326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X, Wang W, Ma J, Guo X, Yu X, Ma X. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22:791–800. doi: 10.1021/bp050386n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maguire T, Novik E, Schloss R, Yarmush M. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;93:581–591. doi: 10.1002/bit.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim C, Chung S, Kim YE, Lee KS, Lee SH, Oh KW, Kang JY. Lab Chip. 2011;11:246–252. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00036a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee KY, Mooney DJ. Prog Polym Sci. 2012;37:106–126. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Augst AD, Kong HJ, Mooney DJ. Macromol Biosci. 2006;6:623–633. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200600069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mata A, Fleischman AJ, Roy S. J Micromech Microeng. 2006;16:276–284. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duarte JC. Fems Microbiol Rev. 1994;13 doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00057.x. 121-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Updegraf.Dm. Anal Biochem. 1969;32:420. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(69)80009-6. &. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi JK, He X. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e56158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rotem A, Abate AR, Utada AS, Van Steijn V, Weitz DA. Lab Chip. 2012;12:4263–4268. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40546f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu X, Ding S, Ding Q, Gray NS, Schultz PG. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1590–1591. doi: 10.1021/ja038950i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yau WW, Tang MK, Chen E, Yaoyao, Wong IW, Lee HS, Lee K. Proteome Sci. 2011;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jasmin, Spray DC, Campos de Carvalho AC, Mendez-Otero R. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:403–412. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hwang YS, Cho J, Tay F, Heng JY, Ho R, Kazarian SG, Williams DR, Boccaccini AR, Polak JM, Mantalaris A. Biomaterials. 2009;30:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang L, Soonpaa MH, Adler ED, Roepke TK, Kattman SJ, Kennedy M, Henckaerts E, Bonham K, Abbott GW, Linden RM, Field LJ, Keller GM. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jugdutt BI. Circulation. 2003;108:1395–1403. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085658.98621.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song K, Nam YJ, Luo X, Qi X, Tan W, Huang GN, Acharya A, Smith CL, Tallquist MD, Neilson EG, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Nature. 2012;485:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.