Summary

Background and objectives

The risk assessment for developing ESRD remains limited in patients with IgA nephropathy (IgAN). The aim of this study was to develop and validate a prediction rule for estimating the individual risk of ESRD in patients with IgAN.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A total of 698 patients with IgAN diagnosed by renal biopsy at Kyushu University Hospital (derivation cohort) between 1982 and 2010 were retrospectively followed. The Oxford classification was used to evaluate the pathologic lesions. The risk factors for developing ESRD were evaluated using a Cox proportional hazard model with a stepwise backward elimination method. The prediction rule was verified using data from 702 patients diagnosed at Japanese Red Cross Fukuoka Hospital (validation cohort) between 1979 and 2002.

Results

In the derivation cohort, 73 patients developed ESRD during the median 4.7-year follow-up. The final prediction model included proteinuria (hazard ratio [HR], 1.30; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.16 to 1.45, every 1 g/24 hours), estimated GFR (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74 to 0.96, every 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2), mesangial proliferation (HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.10 to 3.11), segmental sclerosis (HR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.37 to 7.51), and interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy (T1: HR, 5.30; 95% CI, 2.63 to 10.7; T2: HR, 20.5; 95% CI, 9.05 to 46.5) as independent risk factors for developing ESRD. To create a prediction rule, the score for each variable was weighted by the regression coefficients calculated using the relevant Cox model. The incidence of ESRD increased linearly with increases in the total risk scores (P for trend <0.001). Furthermore, the prediction rule demonstrated good discrimination (c-statistic=0.89) and calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow test, P=0.78) in the validation cohort.

Conclusions

This study developed and validated a new prediction rule using clinical measures and the Oxford classification for developing ESRD in patients with IgAN.

Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common cause of primary GN in the world (1). Many epidemiologic studies have identified risk factors for poor kidney prognosis in patients with IgAN, including age (2), sex (3), hypertension (3,4), decreased estimated GFR (eGFR) (2–5), proteinuria (2,3,6–8), and pathologic severity (2,9,10). In 2009, the Oxford classification of IgAN was proposed by an international working group (11,12). They identified four types of lesions as specific pathologic measures or features associated with the development of ESRD and/or halving of the eGFR: the mesangial hypercellularity score (M), endocapillary hypercellularity (E), segmental glomerulosclerosis (S), and tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis (T) (11). Recent findings have suggested the usefulness of this classification system for predicting kidney prognosis (13–16). However, the prediction ability of the Oxford classification itself for individual kidney prognosis may be limited because of the difficulty in estimating individuals’ absolute risks for future ESRD.

The accurate prediction of kidney prognosis in individual cases is important for determining the therapeutic strategy. Therefore, some investigators have attempted to develop a risk prediction rule for estimating the risk of ESRD in individual patients (2,8,17). However, few studies have evaluated the internal or external validity of their risk prediction tools. Furthermore, these studies have not addressed the extent to which each pathologic measure and clinical variable contributed to the risk prediction of kidney prognosis. Herein, we developed a new clinical and pathologic risk prediction rule using the Oxford classification to identify the subgroup of Japanese patients with IgAN at high risk of developing ESRD, and we verified the external validity of the score in an independent cohort.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Derivation Cohort.

A total of 846 patients with primary IgAN, but not Henoch-Schönlein purpura, were diagnosed by kidney biopsy between January 1982 and December 2010 in six hospitals in the northern region of Kyushu Island in Japan (the Kyushu University Hospital, Hamanomachi Hospital, Munakata Medical Association Hospital, Japan Seamen’s Relief Association Moji Hospital, Karatsu Red Cross Hospital, and Hakujyuji Hospital). Among them, we excluded 85 patients whose biopsy specimen contained <10 glomeruli, 50 patients without available clinical measures, and 13 patients with IgA deposition secondary to such conditions as systemic lupus erythematosus or those with diabetes mellitus. Finally, 698 patients were enrolled in this study, as a derivation cohort. The patients were followed until December 31, 2012.

Validation Cohort.

Seven hundred ninety-four patients with primary IgAN underwent biopsy between October 1979 and September 2002 and were followed for at least 1 year at Japanese Red Cross Fukuoka Hospital. Ninety-two biopsy specimens that contained <10 glomeruli were excluded. The remaining 702 patients were included in the study as a validation cohort (18).

Pathologic Measures

Pathologic lesions were evaluated according to the Oxford classification (11). The mesangial hypercellularity score (M) was defined as M0 if the score was ≤0.5 and M1 if the score was >0.5; endocapillary hypercellularity (E) and segmental glomerulosclerosis (S) were expressed as E0 and S0, respectively, if absent and E1 and S1 if present. Tuft adhesions were regarded as S1 lesions. Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis (T) was semiquantitatively classified according to the percentage of the cortical area involved in the tubular atrophy or interstitial fibrosis: T0 for 0%–25%, T1 for 26%–50%, and T2 for >50%.

Clinical Measures

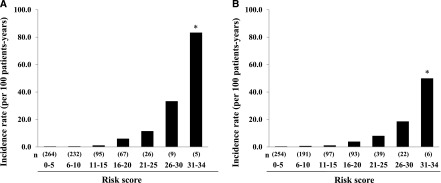

Clinical measures were obtained from medical records at the time of the renal biopsy. They included age, sex, BP, cholesterol levels, triglycerides, serum creatinine, and 24-hour urinary protein excretion or urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio. Hypertension was defined as BP ≥140/90 mmHg and/or current use of antihypertensive agents. Dyslipidemia was defined as serum total cholesterol level≥220 mg/dl and/or serum triglyceride level≥150 mg/dl. The categorical classifications for eGFR and urinary protein excretion were defined using traditional cutoffs for clinical significance (19). Total cholesterol concentrations and triglycerides were determined enzymatically. Serum creatinine was measured by the Jaffe method until April 1988 and by the enzymatic method from May 1988 onward at Kyushu University. At the other participating institutions, serum creatinine was measured by the Jaffe method until December 2000 and by the enzymatic method from January 2001. Serum creatinine values measured by the Jaffe method were converted to values for the enzymatic method by subtracting 0.207 mg/dl (20). The eGFR was calculated using the Schwartz formula in patients younger than age 18 years and the following formula in patients older than age 18 (21–23):

|

The formula for adults proposed by Matsuo et al. (21) is accepted as a more accurate tool for the Japanese population than the previously reported one.

Renal Outcome

The primary endpoint was ESRD, which was defined as the initiation of renal replacement therapy (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or renal transplantation). The renal outcomes were surveyed by medical records or by telephone consultation with the clinics and hospitals the patients visited or with the patients themselves.

Statistical Analyses

In the derivation cohort, we performed univariate analyses to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for each risk factor for the development of ESRD using a Cox proportional hazards model. For these analyses, patients were censored at the date of their death or at the end of follow-up for those still alive. To build the risk prediction model, we selected the independent risk factors for the development of ESRD using a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model with stepwise backward elimination with P<0.05 for remaining variables; in this selection, the clinically or biologically plausible risk factors for ESRD were included as initial candidate variables: age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, urinary protein excretion, eGFR, and pathologic variables based on the Oxford classification. The categories of eGFR 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and urinary protein excretion 0.5–1.0 g/24 hours were included in the final multivariable-adjusted model, which were defined using traditional cutoffs for clinical significance (19), although their β coefficients were not statistically significant. To generate a simple integer-based point score for each variable, we assigned scores by dividing regression coefficients by the value of the smallest coefficient in the model and rounding up to the nearest integer (24). The predicted 5-year absolute risk of incident ESRD according to the total risk score was calculated using relevant Cox models with the baseline survivor function.

For internal and external validation of the prediction rule, we examined the discrimination ability of the models, which was reported as the c-statistic (i.e., area under the curve by logistic regression models with binary outcomes), as well as the calibration of the model by means of the Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-squared statistic in both the derivation and validation cohorts (25). For the Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-squared statistic, the observed 5-year absolute risk for the development of ESRD was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The c-statistics of the different models in the derivation cohort and those of the risk prediction rule in the two independent cohorts were compared using the method of Henley and McNeil (26,27).

The incidence rates of ESRD according to the total risk score were calculated with the person-year method. The risk of incident ESRD per 5-point increment in the total risk score was estimated using the Cox model including the total risk score as a continuous variable. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), and MedCalc software, version 12.3.0.0 (bvba, Mariakerke, Belgium). A two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered to represent statistically significant findings.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted with the approval of the Kyushu University Institutional Review Board for Clinical Research. The ethics committee of all participating institutions granted approval to waive requirement for written, informed consent because of the retrospective nature of the present study.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the mean age of patients in the derivation cohort (n=698) was 36.1 years, and 48.7% of patients were men. Patients in the validation cohort (n=702) had a mean age of 33.1 years; 42.2% of these patients were men. The derivation cohort was significantly older, and the proportion of men was significantly higher than in the validation cohort. The median follow-up times after renal biopsy were 4.7 years and 5.1 years in the derivation and validation cohort, respectively; the difference in follow-up period was not statistically significant. The proportion of heavy urinary protein excretion and the prevalences of Oxford classification grades E1, S1, or T2 were higher in the validation cohort than in the derivation cohort.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients in the derivation and validation cohorts

| Characteristics | Derivation Cohort (n=698) | Validation Cohort (n=702) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 36.1±15.4 | 33.1±14.2 | <0.001 |

| Men (%) | 48.7 | 42.2 | 0.01 |

| Follow-up (yr) | 4.7±1.7–9.3 | 5.1±3.0–8.6 | 0.22 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 125.8±17.7 | 125.9±19.3 | 0.93 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 74.8±13.2 | 75.2±14.2 | 0.57 |

| Hypertensiona (%) | 25.2 | 26.4 | 0.62 |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 202.9±49.5 | 198.3±45.1 | 0.07 |

| Serum triglycerides (mg/dl) | 127.2±80.4 | 123.2±94.7 | 0.40 |

| Urinary protein excretion levels (%) | |||

| <0.5 g/24 hr | 38.0 | 36.6 | <0.001 |

| 0.5–1.0 g/24 hr | 23.4 | 16.8 | |

| 1.0–3.5 g/24 hr | 31.1 | 34.6 | |

| ≥3.5 g/24 hr | 7.5 | 12.0 | |

| Estimated GFR (%) | |||

| ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 72.5 | 74.7 | 0.73 |

| 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 22.2 | 20.8 | |

| 15–29 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 4.3 | 3.4 | |

| <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | |

| Pathologic measures (Oxford classification) (%) | |||

| Mesangial hypercellularity score | |||

| M0 (≤0.5 of glomeruli) | 87.8 | 87.8 | 0.99 |

| M1 (>0.5 of glomeruli) | 12.2 | 12.2 | |

| Endocapillary hypercellularity | |||

| E0 (absence) | 64.3 | 58.1 | 0.02 |

| E1 (presence) | 35.7 | 41.9 | |

| Segmental glomerulosclerosis | |||

| S0 (absence) | 29.7 | 20.8 | <0.001 |

| S1 (presence) | 70.3 | 79.2 | |

| Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis | |||

| T0 (≤25%) | 78.9 | 70.7 | <0.001 |

| T1 (26%–50%) | 14.0 | 17.5 | |

| T2 (>50%) | 7.0 | 11.8 |

Values given are means ± SD or percentages.

Hypertension was defined as BP≥140/90 mmHg and/or current treatment with antihypertensive agents.

Development of the Risk Prediction Model for Kidney Prognosis in the Derivation Cohort

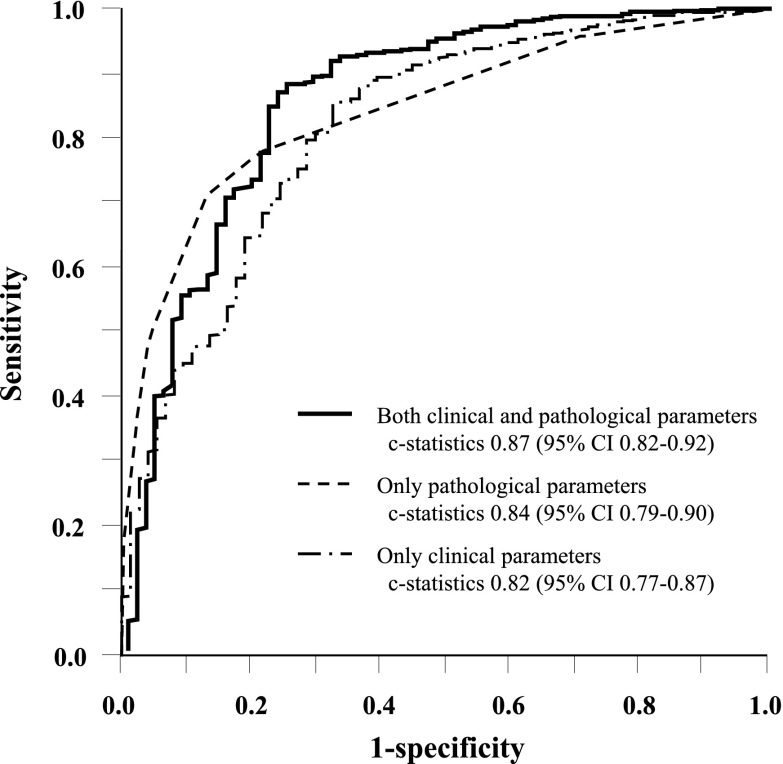

During the follow-up period, 73 patients (10.5%) in the derivation cohort experienced ESRD. Seven variables (hypertension, dyslipidemia, urinary protein excretion, eGFR, and the pathologic measures of the Oxford classification [M, S, and T]) were significantly associated with a higher risk of incident ESRD in univariate analysis (Table 2). Neither age nor sex was a significant risk factor for ESRD. In the multivariate analysis with stepwise backward elimination, two clinical variables—urinary protein excretion (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.45, every 1 g/24 hour) and eGFR (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74 to 0.96, every 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2)—and three pathologic measures—M (HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.10 to 3.11), S (HR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.37 to 7.51), and T (T1: HR, 5.30; 95% CI, 2.63 to 10.7; T2: HR, 20.5; 95% CI, 9.05 to 46.5)—were selected as independent risk factors for incident ESRD. The goodness of fit of the developed risk prediction model was very good on the basis of the c-statistic (0.87; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.92) (Figure 1) and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (chi-squared statistic with 8 d.f.=4.65; P=0.79) (Supplemental Figure 1). In a sensitivity analysis, we compared the risk prediction ability of the models that included only the clinical measures or only the pathologic measures with that of the model that included both the clinical and pathologic measures by means of c-statistics (Figure 1). The results showed that the model including both the clinical and pathologic measures had a significantly higher c-statistic value than the other two models (both P<0.01).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios for the development of ESRD in the derivation cohort

| Variables | Patients (n) | Events (n) | Unadjusted | Multivariate-Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |||

| Age | ||||||

| <30 yr | 307 | 25 | 1.00 (reference) | Not selected | ||

| 30–59 yr | 326 | 43 | 1.23 (0.75 to 2.02) | 0.41 | ||

| ≥60 yr | 65 | 5 | 1.20 (0.46 to 3.16) | 0.71 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 358 | 38 | 1.00 (reference) | Not selected | ||

| Men | 340 | 35 | 1.19 (0.75 to 1.89) | 0.46 | ||

| Hypertensionb | ||||||

| No | 520 | 43 | 1.00 (reference) | Not selected | ||

| Yes | 175 | 29 | 1.89 (1.18 to 3.03) | 0.01 | ||

| Dyslipidemiac | ||||||

| No | 369 | 20 | 1.00 (reference) | Not selected | ||

| Yes | 314 | 52 | 3.44 (2.05 to 5.76) | <0.001 | ||

| Urinary protein excretion | ||||||

| <0.5 g/24 hr | 266 | 2 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 0.5–1.0 g/24 hr | 163 | 8 | 5.85 (1.24 to 27.6) | <0.001 | 3.32 (0.69 to 15.9) | 0.13 |

| 1.0–3.5 g/24 hr | 217 | 47 | 25.3 (6.1 to 104.0) | <0.001 | 6.26 (1.46 to 26.9) | 0.01 |

| ≥3.5 g/24 hr | 52 | 16 | 71.4 (16.4 to 313.9) | <0.001 | 16.2 (3.47 to 75.2) | <0.001 |

| Estimated GFR | ||||||

| ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 506 | 25 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 155 | 26 | 3.96 (2.30 to 6.94) | <0.001 | 1.37 (0.71 to 2.64) | 0.35 |

| 15–29 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 30 | 16 | 30.6 (15.4 to 60.7) | <0.001 | 3.27 (1.45 to 7.40) | 0.003 |

| <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 7 | 6 | 115.9 (45.0 to 298.6) | <0.001 | 13.8 (4.54 to 42.0) | <0.001 |

| Pathologic measures (Oxford classification) | ||||||

| Mesangial hypercellularity score | ||||||

| M0 (≤0.5 of glomeruli) | 613 | 47 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| M1 (>0.5 of glomeruli) | 85 | 26 | 5.48 (3.38 to 8.90) | <0.001 | 1.78 (1.05 to 3.01) | 0.03 |

| Endocapillary hypercellularity | ||||||

| E0 (absence) | 449 | 49 | 1.00 (reference) | Not selected | ||

| E1 (presence) | 249 | 24 | 1.33 (0.81 to 2.19) | 0.26 | ||

| Segmental glomerulosclerosis | ||||||

| S0 (absence) | 207 | 7 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| S1 (presence) | 491 | 66 | 5.25 (2.37 to 11.7) | <0.001 | 3.61 (1.54 to 8.47) | 0.003 |

| Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis | ||||||

| T0 (≤25%) | 551 | 20 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| T1 (26%–50%) | 98 | 24 | 9.95 (5.39 to 18.4) | <0.001 | 5.27 (2.63 to 10.6) | <0.001 |

| T2 (>50%) | 49 | 29 | 57.2 (29.8 to 109.8) | <0.001 | 19.7 (8.47 to 45.7) | <0.001 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Variables were selected by using a Cox proportional hazard model and a stepwise backward method with P<0.05 for remaining variables to determine the risk factors for the development of ESRD. Neither age nor sex was a significant risk factor for the development of ESRD in univariate analysis.

Hypertension was defined as BP≥140/90 mmHg and/or current treatment with antihypertensive agents.

Dyslipidemia was defined as serum total cholesterol≥220 mg/dl and/or serum triglyceride≥150 mg/dl.

Figure 1.

Comparisons of c-statistics among the risk prediction models using only clinical measures, only pathologic measures, or both clinical and pathologic measures in the derivation cohort. The risk prediction model with only clinical measures included urinary protein excretion and estimated GFR. The model with only pathologic measures included mesangial score (M), segmental glomerulosclerosis or adhesion (S), and the severity of tubulointerstitial disease (T). The model with the clinical and pathologic measures included all of the above-mentioned clinical and pathologic measures. CI, confidence interval.

Because the recruitment period for this study was long, there was the possibility that differences in the treatment (e.g., use of renin-angiotensin inhibitors) over time modified the effect of each risk factor on the renal prognosis. However, there was no evidence of significant heterogeneity in the effect of any risk factor on renal prognosis between 1982–1996 and 1997–2010 (all P values for heterogeneity >0.13).

Making a Score-Based Prediction Rule

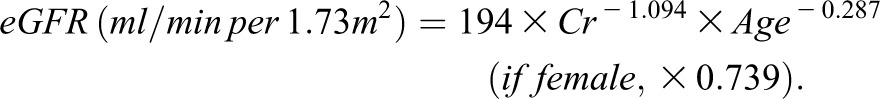

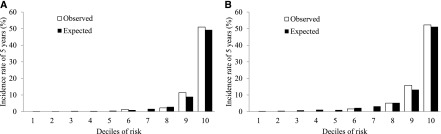

A score-based prediction rule containing five variables selected in multivariate analysis was made using the regression coefficients obtained from the relevant Cox model (Table 2). A regression coefficient of 0.31, which was the smallest value among the variables included, corresponded to 1 point (Table 3). The incidence rate of ESRD increased linearly with increases in the total risk score (P for trend <0.001) (Figure 2A). Every 1-point increment in the total risk score was associated with a 1.33-fold (95% CI, 1.18- to 1.50-fold) increased risk of ESRD. The predicted 5-year absolute risks of ESRD per 1-point increment in the total prediction rule are shown in Table 4. The prediction rule showed the model’s excellent discrimination ability for incident ESRD with a c-statistic of 0.87 (95% CI, 0.82 to 0.92) (Supplemental Table 1) and a good calibration in the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (chi-squared statistic with 8 d.f.=2.80; P=0.95) (Figure 3A).

Table 3.

Risk scores for the development of ESRD

| Variables | Scores |

|---|---|

| Urinary protein excretion | |

| <0.5 g/24 hr | 0 points |

| 0.5–1.0 g/24 hr | 4 points |

| 1.0–3.5 g/24 hr | 6 points |

| ≥3.5 g/24 hr | 9 points |

| Estimated GFR | |

| ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0 points |

| 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 1 point |

| 15–29 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 4 points |

| <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 9 points |

| Pathologic measures (Oxford classification) | |

| Mesangial hypercellularity score | |

| M0 (≤0.5 of glomeruli) | 0 points |

| M1 (>0.5 of glomeruli) | 2 points |

| Segmental glomerulosclerosis | |

| S0 (absence) | 0 points |

| S1 (presence) | 4 points |

| Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis | |

| T0 (≤25%) | 0 points |

| T1 (26%–50%) | 6 points |

| T2 (>50%) | 10 points |

| Maximum total risk scores | 34 points |

Figure 2.

The incidence rate of ESRD by 5-point increments of total risk score in the derivation cohort (A) and the validation cohort (B). *P for trend <0.001.

Table 4.

Predicted 5-year absolute risk of ESRD according to the total risk score

| Total Risk Score (Points) | Predicted 5-Year Absolute Risk (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.07 |

| 1 | 0.10 |

| 2 | 0.13 |

| 3 | 0.18 |

| 4 | 0.24 |

| 5 | 0.33 |

| 6 | 0.45 |

| 7 | 0.60 |

| 8 | 0.81 |

| 9 | 1.09 |

| 10 | 1.47 |

| 11 | 1.98 |

| 12 | 2.66 |

| 13 | 3.58 |

| 14 | 4.80 |

| 15 | 6.42 |

| 16 | 8.57 |

| 17 | 11.40 |

| 18 | 15.10 |

| 19 | 19.80 |

| 20 | 25.70 |

| 21 | 33.10 |

| 22 | 41.90 |

| 23 | 51.90 |

| 24 | 62.80 |

| 25 | 73.70 |

| 26 | 83.50 |

| 27 | 91.20 |

| 28 | 96.20 |

| 29 | 98.80 |

| 30 | 99.70 |

| ≥31 | 100.00 |

Figure 3.

Observed and predicted 5-year absolute risk for the development of ESRD by deciles of risk in the derivation cohort (A) and the validation cohort (B). Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-squared statistic=2.80, d.f.=8, P=0.95 for the derivation cohort and Hosmer-Lemeshow chi-squared statistic=4.75, d.f.=8, P=0.78 for the validation cohort.

External Validation of the Prediction Rule in the Validation Cohort

The prediction rule was externally validated in a population (the validation cohort) independent from the derivation cohort. During the follow-up period, 85 patients (12.1%) experienced ESRD in the validation cohorts. In the validation cohort, the incidence of ESRD also increased linearly with an increase in the total risk score (P for trend <0.001) (Figure 2B). The prediction rule had very good discrimination (c-statistic=0.89; 95% CI, 0.86 to 0.93). There was no evidence of a significant difference in the c-statistics between the derivation and the validation cohorts (P=0.39) (Supplemental Table 1). Furthermore, the prediction rule also showed good calibration in the validation cohort (chi-squared statistic with 8 d.f.=4.75; P=0.78) (Figure 3B).

Subgroup Analysis by Sex or Age

We also conducted analyses stratified by age and sex in both cohorts (Supplemental Table 1). There was no evidence of a significant difference in c-statistics between the derivation and the validation cohorts, regardless of age and sex (all P>0.25). Further, the prediction rule had good discrimination for ESRD (c-statistic=0.86; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.92) and was well calibrated (P=0.61) when analysis was performed (n=650) excluding those younger than 18 years old.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and validated a new prediction rule consisting of five variables: proteinuria; eGFR; and the Oxford histologic grades M, S, and T. Of note, our sensitivity analysis revealed that the model with both clinical and pathologic measures had a statistically better fit than the model with either type of measure alone, suggesting that both clinical and pathologic measures should be taken into account in the risk assessment for kidney prognosis. Furthermore, our prediction rule showed good discriminations of future ESRD and the incidence of ESRD estimated by the prediction model exhibited a good fit with the observed incidence rate of ESRD in both the derivation and validation cohorts. These results suggest that our prediction rule is statistically valid and accurate for the risk assessment of ESRD among Japanese patients with IgAN. We believe that this score will be useful for determining the initial therapeutic strategies of patients with IgAN.

Several risk scores for developing ESRD in patients with IgAN have been reported previously (2,8,17). However, these studies had several limitations. The study of Goto et al., in which 2283 Japanese patients were followed up for a median of 7.3 years, had the limitations inherent in a mail-based survey: namely, the authors could not collect complete data for about a quarter of the participants or check the quality of the datasets (2,28). Berthoux et al. made a risk score from the data of 332 French patients for a median 11.3-year follow-up (8), but their score evaluated histologic lesions using their own original pathologic classification system (29,30), which is not generally accepted. Xie et al. developed a risk score for predicting ESRD in 619 Chinese patients followed for an average of 3.4 years and showed that their score had a better predictive performance on their dataset than previously published risk scores (17). However, their score has not been verified in an independent validation cohort. Furthermore, none of these previously published risk scores used an internationally accepted pathologic grading system, such as the Oxford classification (12,14,31). To our knowledge, our study is the first investigation attempting to develop a risk score using the Oxford classification and to verify its external validity in an independent cohort.

In the present study, we identified five variables as risk factors for ESRD by multivariate analysis—proteinuria, eGFR, and the Oxford pathologic measures—which is consistent with many prior investigations (1–7,9,10,32–34). In particular, increased proteinuria and decreased eGFR have been well acknowledged as major risk factors for ESRD among patients with IgAN (3,5,6,9,35). In this study, M, S, and T were independently associated with renal outcome. T has been established as a significant prognostic factor associated with renal outcome in other studies, whereas the effects of M and S on renal prognosis have been inconsistent among studies (11,15,16,36). Some reports showed that M or S were not both selected as risk factors for future ESRD in multivariate analysis (15,16,36). These inconsistencies may be due to insufficient statistical power resulting from the small sample sizes of the studies. Like most previous studies, the present study failed to reveal a significant association of E with renal prognosis (15,18,36). Therefore, the variables included in our prediction rule would seem to be reasonable for application to research or clinical studies.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, one-time measurement of each risk factor may have caused the misclassification of study patients. Such misclassification would weaken the association found in this study, biasing the results toward the null hypothesis. Specifically, a previous study found that average BP is a more important predictor of renal prognosis than a single measurement at the time of biopsy or first visit (6,37). Therefore, the lack of information on average BP during the follow-up period would tend toward the underestimation of the effect of BP on the renal prognosis, which may be why hypertension was not statistically selected as a risk factor for ESRD in this study. Second, we could not consider the effect of therapeutic intervention on the kidney prognosis. Patients with heavy proteinuria and advanced pathologic findings were likely to receive aggressive treatment (e.g., steroid and cytotoxic agents), which may have shifted the effect of these risk factors on the risk of ESRD downward. Finally, the generalizability of our prediction rule for populations of other races may be limited. It has been reported that the renal survival rates in Japanese patients with IgAN resemble those in Europe and China (35,38,39). However, the patients in the present study showed only 10% of ESRD, which reflected the relatively “low-risk” features of our cohort compared with other published cohorts. In fact, most of our patients had relatively low-grade proteinuria (<1 g/d) and low-risk pathologic features, and fewer had hypertension and advanced CKD stage than those in previous studies (6,8,17,37). Thus, one should take care in applying the risk scores developed in the present study to a traditionally high-risk population of patients with IgAN. It may be necessary to evaluate the validity of our prediction rule in other populations. However, we believe that this prediction rule may also provide useful risk assessments for ESRD in patients with IgAN in populations of other races or ethnic groups.

In conclusion, we have developed a new prediction rule for developing ESRD in patients with IgAN and verified its validity in an independent cohort. This prediction rule should provide a useful guide to estimate the individual risk for ESRD in patients with IgAN and may be effective at identifying those at high risk for the future development of ESRD. Further investigations will be needed to fully confirm that therapeutic interventions based on this prediction rule can reduce the burden of patients with IgAN.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express our appreciation to the investigators in the participating institutions: Tetsuhiko Yoshida, Kei Hori, Takashi Inenaga, Akinori Nagashima, Tadashi Hirano, and Koji Mitsuiki.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 23590400 and no. 24593302) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.03480413/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.D’Amico G: The commonest glomerulonephritis in the world: IgA nephropathy. Q J Med 64: 709–727, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goto M, Wakai K, Kawamura T, Ando M, Endoh M, Tomino Y: A scoring system to predict renal outcome in IgA nephropathy: A nationwide 10-year prospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 3068–3074, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lv J, Zhang H, Zhou Y, Li G, Zou W, Wang H: Natural history of immunoglobulin A nephropathy and predictive factors of prognosis: A long-term follow up of 204 cases in China. Nephrology (Carlton) 13: 242–246, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li PK, Ho KK, Szeto CC, Yu L, Lai FM: Prognostic indicators of IgA nephropathy in the Chinese—clinical and pathological perspectives. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 64–69, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radford MG, Jr, Donadio JV, Jr, Bergstralh EJ, Grande JP: Predicting renal outcome in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 199–207, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reich HN, Troyanov S, Scholey JW, Cattran DC, Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry : Remission of proteinuria improves prognosis in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 3177–3183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donadio JV, Bergstralh EJ, Grande JP, Rademcher DM: Proteinuria patterns and their association with subsequent end-stage renal disease in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1197–1203, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berthoux F, Mohey H, Laurent B, Mariat C, Afiani A, Thibaudin L: Predicting the risk for dialysis or death in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 752–761, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HS, Lee MS, Lee SM, Lee SY, Lee ES, Lee EY, Park SY, Han JS, Kim S, Lee JS: Histological grading of IgA nephropathy predicting renal outcome: Revisiting H. S. Lee’s glomerular grading system. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 342–348, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manno C, Strippoli GF, D’Altri C, Torres D, Rossini M, Schena FP: A novel simpler histological classification for renal survival in IgA nephropathy: A retrospective study. Am J Kidney Dis 49: 763–775, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cattran DC, Coppo R, Cook HT, Feehally J, Roberts IS, Troyanov S, Alpers CE, Amore A, Barratt J, Berthoux F, Bonsib S, Bruijn JA, D’Agati V, D’Amico G, Emancipator S, Emma F, Ferrario F, Fervenza FC, Florquin S, Fogo A, Geddes CC, Groene HJ, Haas M, Herzenberg AM, Hill PA, Hogg RJ, Hsu SI, Jennette JC, Joh K, Julian BA, Kawamura T, Lai FM, Leung CB, Li LS, Li PK, Liu ZH, Mackinnon B, Mezzano S, Schena FP, Tomino Y, Walker PD, Wang H, Weening JJ, Yoshikawa N, Zhang H, Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society : The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int 76: 534–545, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts IS, Cook HT, Troyanov S, Alpers CE, Amore A, Barratt J, Berthoux F, Bonsib S, Bruijn JA, Cattran DC, Coppo R, D’Agati V, D’Amico G, Emancipator S, Emma F, Feehally J, Ferrario F, Fervenza FC, Florquin S, Fogo A, Geddes CC, Groene HJ, Haas M, Herzenberg AM, Hill PA, Hogg RJ, Hsu SI, Jennette JC, Joh K, Julian BA, Kawamura T, Lai FM, Li LS, Li PK, Liu ZH, Mackinnon B, Mezzano S, Schena FP, Tomino Y, Walker PD, Wang H, Weening JJ, Yoshikawa N, Zhang H, Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society : The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int 76: 546–556, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alamartine E, Sauron C, Laurent B, Sury A, Seffert A, Mariat C: The use of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy to predict renal survival. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2384–2388, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herzenberg AM, Fogo AB, Reich HN, Troyanov S, Bavbek N, Massat AE, Hunley TE, Hladunewich MA, Julian BA, Fervenza FC, Cattran DC: Validation of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 80: 310–317, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yau T, Korbet SM, Schwartz MM, Cimbaluk DJ: The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: A retrospective analysis. Am J Nephrol 34: 435–444, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang SH, Choi SR, Park HS, Lee JY, Sun IO, Hwang HS, Chung BH, Park CW, Yang CW, Kim YS, Choi YJ, Choi BS: The Oxford classification as a predictor of prognosis in patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 252–258, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie J, Kiryluk K, Wang W, Wang Z, Guo S, Shen P, Ren H, Pan X, Chen X, Zhang W, Li X, Shi H, Li Y, Gharavi AG, Chen N: Predicting progression of IgA nephropathy: New clinical progression risk score. PLoS ONE 7: e38904, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katafuchi R, Ninomiya T, Nagata M, Mitsuiki K, Hirakata H: Validation study of Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: The significance of extracapillary proliferation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2806–2813, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, El Nahas M, Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, Kasiske BL, Eckardt KU: The definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: A KDIGO Controversies Conference report. Kidney Int 80: 17–28, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imai E, Horio M, Nitta K, Yamagata K, Iseki K, Hara S, Ura N, Kiyohara Y, Hirakata H, Watanabe T, Moriyama T, Ando Y, Inaguma D, Narita I, Iso H, Wakai K, Yasuda Y, Tsukamoto Y, Ito S, Makino H, Hishida A, Matsuo S: Estimation of glomerular filtration rate by the MDRD study equation modified for Japanese patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol 11: 41–50, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K, Yamagata K, Tomino Y, Yokoyama H, Hishida A, Collaborators developing the Japanese equation for estimated GFR : Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 982–992, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz GJ, Brion LP, Spitzer A: The use of plasma creatinine concentration for estimating glomerular filtration rate in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am 34: 571–590, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM, Jr, Spitzer A: A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics 58: 259–263, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moons KG, Harrell FE, Steyerberg EW: Should scoring rules be based on odds ratios or regression coefficients? J Clin Epidemiol 55: 1054–1055, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parzen M, Lipsitz SR: A global goodness-of-fit statistic for Cox regression models. Biometrics 55: 580–584, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ: A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 148: 839–843, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ: The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143: 29–36, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakai K, Kawamura T, Endoh M, Kojima M, Tomino Y, Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y, Inaba Y, Sakai H: A scoring system to predict renal outcome in IgA nephropathy: From a nationwide prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 2800–2808, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alamartine E, Sabatier JC, Guerin C, Berliet JM, Berthoux F: Prognostic factors in mesangial IgA glomerulonephritis: An extensive study with univariate and multivariate analyses. Am J Kidney Dis 18: 12–19, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alamartine E, Sabatier JC, Berthoux FC: Comparison of pathological lesions on repeated renal biopsies in 73 patients with primary IgA glomerulonephritis: Value of quantitative scoring and approach to final prognosis. Clin Nephrol 34: 45–51, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng CH, Le W, Ni Z, Zhang M, Miao L, Luo P, Wang R, Lv Z, Chen J, Tian J, Chen N, Pan X, Fu P, Hu Z, Wang L, Fan Q, Zheng H, Zhang D, Wang Y, Huo Y, Lin H, Chen S, Sun S, Wang Y, Liu Z, Liu D, Ma L, Pan T, Zhang A, Jiang X, Xing C, Sun B, Zhou Q, Tang W, Liu F, Liu Y, Liang S, Xu F, Huang Q, Shen H, Wang J, Shyr Y, Phillips S, Troyanov S, Fogo A, Liu ZH: A multicenter application and evaluation of the oxford classification of IgA nephropathy in adult Chinese patients. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 812–820, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haas M: Histologic subclassification of IgA nephropathy: A clinicopathologic study of 244 cases. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 829–842, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang HS, Kim BS, Shin YS, Yoon HE, Song JC, Choi BS, Park CW, Yang CW, Kim YS, Bang BK: Predictors for progression in immunoglobulin A nephropathy with significant proteinuria. Nephrology (Carlton) 15: 236–241, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber CL, Rose CL, Magil AB: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in mild IgA nephropathy: A clinical-pathologic study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 483–488, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koyama A, Igarashi M, Kobayashi M, Research Group on Progressive Renal Diseases : Natural history and risk factors for immunoglobulin A nephropathy in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 526–532, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi SF, Wang SX, Jiang L, Lv JC, Liu LJ, Chen YQ, Zhu SN, Liu G, Zou WZ, Zhang H, Wang HY: Pathologic predictors of renal outcome and therapeutic efficacy in IgA nephropathy: Validation of the oxford classification. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2175–2184, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartosik LP, Lajoie G, Sugar L, Cattran DC: Predicting progression in IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 728–735, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Amico G: Influence of clinical and histological features on actuarial renal survival in adult patients with idiopathic IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: Survey of the recent literature. Am J Kidney Dis 20: 315–323, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li L: End-stage renal disease in China. Kidney Int 49: 287–301, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.