Abstract

The main genetic factor related to HIV-1 resistance is the CCR5-Δ32 mutation; however, the homozygous genotype is uncommon. The CCR5-Δ32 mutation along with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the CCR5 promoter and the CCR2-V64I mutation have been included in seven human haplogroups (HH) previously associated with resistance/susceptibility to HIV-1 infection and different rates of AIDS progression. Here, we determined the association of the CCR5 promoter SNPs, the CCR5-Δ32 mutation, CCR2-V64I SNP, and HH frequencies with resistance/susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in a cohort of HIV-1-serodiscordant couples from Colombia. Seventy HIV-1-exposed, but seronegative (HESN) individuals, 57 seropositives (SP), and 112 healthy controls (HC) were included. The CCR5-Δ32 mutation and CCR2-V64I SNP were identified by PCR, and the CCR5 promoter SNPs were evaluated by sequencing. None of the individuals exhibited a homozygous Δ32 genotype; the CCR2-I allele was more frequent in HESN (34%) than HC (23%) (p=0.039, OR=1.672). The frequency of the 29G allele was higher in SP than HC (p=0.003, OR=3). HHF2 showed a higher frequency in HC (19%) than SP (9%) (p=0.027), while HHG1 was more frequent in SP (11.1%) than in HC (4.2%) (p=0.019). The AGACCAC-CCR2-I-CCR5 wild-type haplotype showed a higher frequency in SP (14.2%) than in HC (3.7%) (p=0.001). In conclusion, the CCR5-Δ32 allele is not responsible for HIV-1 resistance in this HESN group; however, the CCR2-I allele could be protective, while the 29G allele might increase the likelihood of acquiring HIV-1 infection. HHG1 and the AGACCAC-CCR2-I-CCR5 wild-type haplotype might promote HIV-1 infection while HHF2 might be related to resistance. However, additional studies are required to evaluate the implications of these findings.

Introduction

To date, more than 25 million individuals have died from HIV-related causes and currently around 33 million persons are living with HIV worldwide.1 Our current knowledge of HIV pathogenesis suggests that genetic variants can modulate the immune response and viral replication.2 In fact, certain persons exhibit resistance to HIV-1 infection despite multiple and repeated exposures to the virus; they are known as HIV-1-exposed, but seronegative (HESN) individuals.3,4 This group includes persons who have repeated unprotected sexual intercourse with a seropositive (SP) individual, such as HIV-1-serodiscordant couples5; these persons have been reported to be at high risk of HIV-1 acquisition.6 Thus, HESNs make it possible to identify new elements controlling either resistance or susceptibility to HIV-1 infection and that may lead to the development of new therapeutic targets.

The only genetic factor closely related to natural resistance to HIV-1 infection is the Δ32 mutation in the CCR5 receptor gene (CCR5-Δ32), which was first described in HESNs.7 Homozygous persons for this mutation (Δ32/Δ32) exhibit a high level of resistance to HIV-1 infection, in particular to R5 strains.8 In contrast, heterozygous persons are susceptible to infection, but exhibit slow progression to AIDS.7 In addition, different single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the CCR5 promoter have been associated with different rate of AIDS progression9,10 and resistance to HIV-1 infection.11 In fact, the CCR5-Δ32 and CCR5-2459G alleles have been associated with a negative effect on the expression of CCR5 in both T-helper cells and monocytes from HESNs.12 Likewise, SP individuals with the CCR5-2459G/G genotype progress more slowly to AIDS than those with the A/A genotype.13 Similarly, the CCR5-2459G and CCR5-2135T SNPs were associated with a protective effect against vertical transmission of HIV-1.14

In vitro studies have demonstrated that HIV-1 can use alternative coreceptors, such as CCR2.15 A genetic variant of CCR2 (CCR2-V64I) leads to variations in the CCR2 transmembrane region and has been associated with slow progression to AIDS; however, its effect on susceptibility to acquire HIV-1 infection has not been defined to date.16

Previously, seven evolutionarily distinct human haplogroups (HH): HHA, -B, -C, -D, -E, -F (-F1 and -F2), and -G (-G1 and -G2) have been described; each haplogroup includes the combination of a unique SNP in the CCR5 regulatory region with the presence or absence of the CCR2-V64I and the CCR5-Δ32 mutations (Table 1).10 HHG2, which includes the CCR5-Δ32 mutation, was reported to be protective in children born to HIV-positive mothers.17 The HHA and HHF2 haplotypes, which are more frequent in African Americans than in whites, have been associated with delayed disease in SP individuals; moreover, the genotype HHC/HHG2 was related to the strongest protective effect in the same white population.18 Several studies have associated homozygosity for HHE with susceptibility to HIV infection, accelerated progression to AIDS, and rapid decrease of CD4 counts.16,19,20 Nonetheless, the role of HH in natural resistance to HIV infection has not been clarified.

Table 1.

Graphic Classification of Human Haplogroups

| SNPs nomenclature | CCR2 V64I (G190A) | CCR5 | CCR5 Δ32 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF031236 | A29G | G208T | G303A | T627C | C630T | A676G | C927T | ||

| Translational site | −2733 | −2554 | −2459 | −2135 | −2132 | −2086 | −1835 | ||

| U95626 | 58755A/G | 58934G/T | 59029G/A | 59353T/C | 59356C/T | 59402A/G | 59653C/T | ||

| Reference SNP cluster | rs1799864 | rs2856758 | rs2734648 | rs1799987 | rs1799988 | rs41469351 | rs1800023 | rs1800024 | rs333 |

| HH | |||||||||

| A | V | A | G | G | T | C | A | C | WT |

| B | V | A | T | G | T | C | A | C | WT |

| C | V | A | T | G | T | C | G | C | WT |

| D | V | A | T | G | T | T | A | C | WT |

| E | V | A | G | A | C | C | A | C | WT |

| F | |||||||||

| F1 | V | A | G | A | C | C | A | T | WT |

| F2 | I | A | G | A | C | C | A | T | WT |

| G | |||||||||

| G1 | V | G | G | A | C | C | A | C | WT |

| G2 | V | G | G | A | C | C | A | C | Δ32 |

Human haplogroup classification was obtained from Mummidi et al.10

HH, human haplogroup; SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Determining which immunological and genetic factors influence resistance to HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS is a worldwide objective, since this knowledge could lead to the development of vaccines to prevent infection and/or disease progression. This study was carried out to evaluate the association of natural resistance to HIV-1 infection with the frequency of CCR5 promoter SNPs, Δ32 mutation, CCR2-V64I SNP, and HH in a cohort of HIV-1-serodiscordant couples from Colombia.

Materials and Methods

Study populations

A total of 70 HESN and 57 SP individuals, obtained from a cohort of HIV-1-serodiscordant couples, was recruited from HIV-1 care programs in Medellin and Santa Marta, Colombia. The inclusion criteria for HESN were (1) unprotected sexual intercourse with an SP individual more than 10 times in the previous 6 months within 2 years of enrollment; (2) a negative HIV-1/2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test, along with a negative nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the env gene of HIV-1 within 1 month of sampling; and (3) SP partners were either highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) naive or had a detectable viral load.21 Healthy controls (HCs) (112 individuals) were adult volunteers with a low risk of HIV exposure evaluated by means of a questionnaire for risk behavior completed at the time of sampling; these control individuals had ethnic backgrounds similar to the HESN and SP individuals. All individuals signed an informed consent approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Antioquia, prepared according to the Colombian Government Legislation.

Detection of the CCR5-Δ32 mutation and identification of the CCR2-V64I SNP

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using cell lysis and protein precipitation solutions (Gentra/Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the protocol described by the manufacturer. The CCR5-Δ32 mutation and the CCR2-V64I SNP were detected by PCR as previously described.22,23

Genotyping of SNPs in the promoter region of the CCR5 gene

DNA was amplified by PCR, using 4 μl of DNA (∼100 ng/μl), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Bioline, IL), and 0.6 μM of each primer (Forward: 5'-AGATGTCACCA ACCGCCAAGAGA-3' and Reverse: 5'- TACTAACTGTGCC ATGAAACTGAT-3'). The thermal conditions were as follows: 95°C for 3 min, 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s with an increase of 2 s per cycle and final extension of 72°C for 5 min. A PCR product of 1,466 bp was obtained. In addition, internal primers (Forward: 5'-TCCAGGATCCCCC TCTACATT-3' and Reverse: 5'-TCTCTGCTCATCCCACTA CAC-3') were used only for sequencing through the commercial service from Macrogen (Macrogen, Korea).

Statistical analysis

Genetic linkage analysis and the frequencies of haplotypes were evaluated using the Haploview software.24 Associations between the allele, genotype and haplotype frequencies, and susceptibility/resistance to HIV-1 infection were statistically compared by either the Chi-square or Fisher test using the plink software v.1.07.25 A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic data

We evaluated 112 HC, 70 HESN, and 57 SP individuals; 57 HESNs and SPs correspond to HIV-1-discordant couples. There were no significant differences in gender among groups (p=0.392) and all groups had similar ethnic backgrounds. Additionally, 11 (19%) SP individuals were not receiving antiretroviral therapy, and the median viral load in the SPs was 2,569 RNA copies/ml (range, 400–493,000 copies/ml), suggesting that the risk of infection from SPs to HESNs was moderate. However, HESNs showed a monthly average of eight unprotected sexual contacts with their SP partner, thereby increasing the risk of acquiring the virus. In addition, 47% of SPs and 27% of HESNs reported other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) before the time of sampling. Finally, although the majority of sexual orientation was heterosexual, with 73% and 87% for SPs and HESNs, respectively, there were also bisexual (22% and 8% for SPs and HESNs, respectively) and homosexual (5% for both SPs and HESNs) orientations. Thus, this cohort of HESN exhibited a high risk of being infected with HIV-1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Profile

| |

Population |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | HC (n=112) | HESN (n=70) | SP (n=57) |

| Age median (range) | 28 (19–54) | 34 (17–61) | 34 (17–51) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 46 (41%) | 36 (51%) | 26 (46%) |

| Female | 66 (59%) | 34 (49%) | 31 (54%) |

| Viral load (copies/ml) median (range) | ND | ND | 2569 (50–493,000) |

| T CD4+ lymphocytes (cells/μl) median (range) | ND | ND | 361 (17–909) |

HC, healthy control; HESN, HIV-1-exposed seronegative; SP, seropositive; ND, no data.

To rule out stratification bias in SPs and HESNs, we analyzed the frequency of 17 SNPs with delta value ≥0.40, which indicate that these allelic variants can be used as ancestry informative markers (AIMs). In addition, to establish the principal component of ancestry we used the previously reported frequencies in samples from Africa and Europe (1,000 genome catalog). We found similar ancestry component, and pair-wise fixation index (FST) values indicate that our population is not stratified (for details see Supplementary Tables S1, S2, and S3; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid).

The CCR5-Δ32 mutation does not account for the resistance observed in this HESN cohort

Since the CCR5-Δ32 mutation is the major genetic factor so far associated with natural resistance to HIV-1 infection, its frequency in this cohort of 239 individuals was evaluated. None of the individuals exhibited the homozygous Δ32 genotype; only five HCs, seven HESNs, and six SPs were Δ32 heterozygous (Table 3). No significant differences were observed among the groups evaluated. Additionally, CCR5-Δ32 was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) according to the expected frequencies (p>0.05). These results suggest that other factors influence the resistance to HIV-1 infection in the Colombian HESN cohort.

Table 3.

Genotype and Allele Frequencies of the CCR5-Δ32 Mutation and the CCR2-V64I Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

| |

Population n (frequency) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HC | HESN | SP | |

| CCR5-Δ32 genotypes | |||

| CCR5/CCR5 | 107 (0.955) | 63 (0.900) | 51 (0.895) |

| CCR5/Δ32 | 5 (0.045) | 7 (0.100) | 6 (0.105) |

| Δ32/Δ32 | 0 (0.000) | 0 (0.000) | 0 (0.000) |

| CCR5-Δ32 alleles | |||

| CCR5 | 219 (0.978) | 133 (0.950) | 108 (0.947) |

| Δ32 | 5 (0.022) | 7 (0.050) | 6 (0.053) |

| CCR2-V64I genotypes | |||

| CCR2 V/CCR2 V | 70 (0.625) | 28 (0.400) | 27 (0.474) |

| CCR2 V/CCR2 I | 32 (0.286) | 37 (0.529) | 27 (0.474) |

| CCR2 I/ CCR2 Ia | 10 (0.089) | 5 (0.071) | 3 (0.052) |

| CCR2-V64I alleles | |||

| CCR2 V | 172 (0.768) | 93 (0.664) | 81 (0.710) |

| CCR2 I | 52 (0.232) | 47 (0.336) | 33 (0.290) |

p=0.003 assuming dominant model between HC and HESN, OR=2.5 and 95% CI=1.355 to 4.613.

p=0.004 comparing all genotypes between HC and HESN for CCR2-V64I SNP.

p=0.0393 comparing all alleles between HC and HESN for CCR2-V64I SNP, OR=1.672 and 95% CI=1.047 to 2.67.

HC, healthy control; HESN, HIV-1-exposed seronegative; SP, seropositive.

CCR2-V64I SNP could be influencing the resistance to HIV infection

The CCR2-V64I SNP has been previously associated with delayed progression to AIDS; however, its role during natural resistance to HIV-1 infection is not clear. Remarkably, when comparing all genotypes we observed statistical differences between HCs and HESNs (p=0.004); assuming the dominant model, in which the variant homozygous genotype (I/I) and the heterozygous genotype (V/I) were added and compared with the wild-type homozygous genotype (V/V), significant differences between HCs (37%) and HESNs were detected (60%) (p=0.003, OR=2.5, and CI 95%=1.355 to 4.613) (Table 3). In addition, the allele frequency of CCR2-I was significant higher in the HESN group compared with HC individuals: 34% and 23%, respectively (p=0.039, OR=1.672 and 95% CI=1.047 to 2.67) (Table 3). Nonetheless, after Bonferroni adjustment, the significance was lost, suggesting that the difference was not statistically strong. No differences were observed when comparing the rest of the groups. Finally, we found Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the CCR2-V64I SNP among all groups (p>0.05).

Frequencies of CCR5 promoter SNPs

The genotype and allele frequencies of the CCR5 promoter SNPs from HCs, HESNs, and SPs are shown in Tables 4 and 5. The frequency of the SNP A29G at the genotype and allele levels was significantly different between HC and SP individuals: p=0.006 and p=0.003 (OR=3 and 95% CI=1.443 to 6.235), respectively. This significance was maintained after Bonferroni multitest adjustment. The frequency of the A29G-GG genotype was greater in SP than in HC individuals (7% vs. 0%, respectively); likewise, SPs showed a significantly higher frequency of the G allele compared with HC: 16.7% and 6.3%, respectively. In addition, assuming the dominant model, we found significant differences between HCs and SPs (p=0.03118, OR=2.5 and 95% CI=1.108 to 5.638) (Table 4). The AA genotype of the SNP A676G was more frequent in SPs (68.4%) compared with HCs (54.1%, p=0.028). However, HWE was lost for the A676G SNP in the SP group (p=0.004). The HESN and HC groups were in HWE.

Table 4.

Genotypic Frequencies of CCR5 Promoter Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms

| |

|

Population n (frequency) |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Genotype | HC | HESN | SP | p value |

| A29G** | A/A | 98 (0.875) | 55 (0.786) | 42 (0.737) | |

| A/G | 14 (0.125) | 14 (0.200) | 11 (0.193) | p=0.017* | |

| G/G | 0 (0.000) | 1 (0.014) | 4 (0.070) | p=0.006† | |

| G208T | G/G | 56 (0.500) | 36 (0.514) | 31 (0.544) | |

| G/T | 41 (0.366) | 23 (0.329) | 15 (0.263) | ||

| T/T | 15 (0.134) | 11 (0.157) | 11 (0.193) | ||

| G303A | G/G | 24 (0.216) | 14 (0.200) | 14 (0.246) | |

| G/A | 42 (0.378) | 29 (0.414) | 22 (0.386) | ||

| A/A | 45 (0.405) | 27 (0.386) | 21 (0.368) | ||

| T521C | T/T | 112 (1.000) | 69 (0.986) | 57 (1.000) | |

| T/C | 0 (0.000) | 1 (0.014) | 0 (0.000) | ||

| C/C | 0 (0.000) | 0 (0.000) | 0 (0.000) | ||

| T627C | T/T | 25 (0.225) | 17 (0.243) | 12 (0.211) | |

| T/C | 44 (0.396) | 28 (0.400) | 22 (0.386) | ||

| C/C | 42 (0.378) | 25 (0.357) | 23 (0.403) | ||

| C630T | C/C | 100 (0.901) | 64 (0.914) | 50 (0.877) | |

| C/T | 11 (0.099) | 6 (0.086) | 7 (0.123) | ||

| T/T | 0 (0.000) | 0 (0.000) | 0 (0.000) | ||

| A676G | A/A | 60 (0.541) | 40 (0.571) | 39 (0.684) | |

| A/G | 41 (0.369) | 22 (0.314) | 10 (0.175) | p=0.028† | |

| G/G | 10 (0.090) | 8 (0.114) | 8 (0.140) | ||

| C927T | C/C | 74 (0.667) | 48 (0.686) | 44 (0.772) | |

| C/T | 25 (0.225) | 19 (0.271) | 12 (0.211) | p=0.054† | |

| T/T | 12 (0.108) | 3 (0.043) | 1 (0.017) | ||

| A1076C | A/A | 101 (0.909) | 64 (0.914) | 51 (0.895) | |

| A/C | 9 (0.081) | 5 (0.071) | 6 (0.105) | ||

| C/C | 1 (0.009) | 1 (0.014) | 0 (0.000) | ||

p value comparing all genotypes among groups.

p value comparing all genotypes between HC and SP.

p=0.03118 assuming dominant model between HC and SP, OR=2.5 and 95% CI=1.108 to 5.638.

HC, healthy control; HESN, HIV-1-exposed seronegative; SP, seropositive; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Table 5.

Allelic Frequencies of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the CCR5 Promoter

| |

|

Population n (frequency) |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Allele | HC | HESN | SP | p value |

| A29G | A | 210 (0.937) | 124 (0.886) | 95 (0.833) | p=0.012* |

| G | 14 (0.063) | 16 (0.114) | 19 (0.167) | p=0.003† OR=3 95% CI=1.443–6.235 | |

| G208T | G | 153 (0.683) | 95 (0.679) | 77 (0.675) | |

| T | 71 (0.317) | 45 (0.321) | 37 (0.325) | ||

| G303A | G | 90 (0.405) | 57 (0.407) | 50 (0.439) | |

| A | 132 (0.595) | 83 (0.593) | 64 (0.561) | ||

| T521C | T | 224 (1.000) | 139 (0.993) | 114 (1.000) | |

| C | 0 (0.000) | 1 (0.007) | 0 (0.000) | ||

| T627C | T | 94 (0.423) | 62 (0.443) | 46 (0.404) | |

| C | 128 (0.577) | 78 (0.558) | 68 (0.596) | ||

| C630T | C | 211 (0.950) | 134 (0.957) | 107 (0.939) | |

| T | 11 (0.050) | 6 (0.043) | 7 (0.061) | ||

| A676G | A | 161 (0.725) | 102 (0.729) | 88 (0.772) | |

| G | 61 (0.275) | 38 (0.271) | 26 (0.228) | ||

| C927T | C | 173 (0.779) | 115 (0.821) | 100 (0.877) | p=0.031† OR=0.49 95% CI=0.259–0.940 |

| T | 49 (0.221) | 25 (0.179) | 14 (0.123) | ||

| A1076C | A | 211 (0.950) | 133 (0.950) | 108 (0.947) | |

| C | 11 (0.050) | 7 (0.050) | 6 (0.053) | ||

p value comparing all alleles among groups.

p value comparing all alleles between HC and SP.

HC, healthy control; HESN, HIV-1-exposed seronegative; SP, seropositive.

Additionally, we observed that the allele 927T was more prevalent in HCs (22%) compared to SPs (12%, with p=0.031, OR=0.49, and 95% CI=0.259 to 0.940) (Table 5). There were no significant differences in the remaining SNPs among the groups. In addition to the previously reported SNPs at the CCR5 promoter,10 one new variant was observed that included a T-to-C change at position 521 (T521C) or -2353, according to the translational site. The T521C SNP was observed in only one individual of the HESN group, who was heterozygous (T/C) at this position.

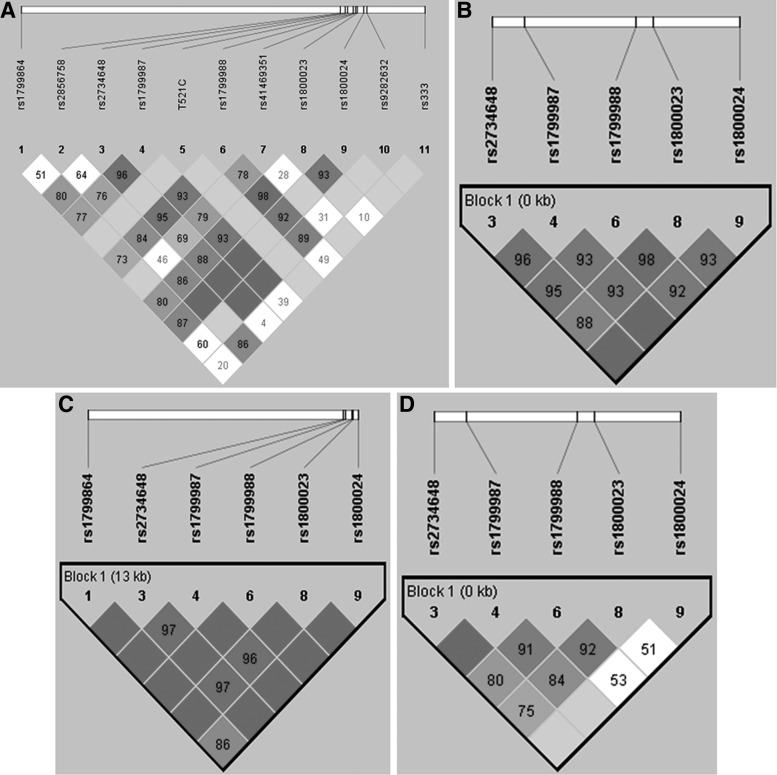

Linkage disequilibrium in chemokine receptor genes

The analysis of linkage disequilibrium (LD) including all populations showed a strong LD among five SNPs in the CCR5 promoter (G208T, G303A, T627C, A676G, and C927T) (Fig. 1A and B); in contrast, there was a weak or no LD between the CCR2-V64I SNP and each of the following CCR5 promoter SNPs: A29G, C630T, T521C, and A1076C (Fig. 1A). Additionally, a strong LD between the CCR5-Δ32 mutation and the A29G SNP was observed (D'=0.867; r2=0.258).

FIG. 1.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) values among markers are indicated at the intercept of the two markers on the matrix. Dark gray boxes indicate strong LD, whereas white boxes indicate weak LD. (A) LD was defined for all single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in all groups; HIV-1-exposed, but seronegative individuals (HESN), healthy controls (HC), and seropositive (SP) using Haploview. (B) Haplotype block limits were defined for five SNPs in all groups; one main haplotype block is outlined within the black triangles. (C) One main haplotype block containing six SNPs is delimited in the HC group. (D) One main haplotype block containing five SNPs is delimited in the SP group.

The HESN group showed a strong LD among five SNPs mentioned above (G208T, G303A, T627C, A676G, and C927T). Interestingly, in the HC group a strong LD was found among these five SNPs and the CCR2-V64I SNP (Fig. 1C). In contrast, LD was weak or nonexistent between the C927T SNP and the G208T, G303A, T627C, and A676G SNPs in the SP group (Fig. 1D). In particular, we found high LD within the G208T, G303A, T627C, and A676G SNPs in the SP group (D'>0.9 and r2=0.6). Finally, we found strong D' but weak r2 between C927T and G208T, G303A, T627C, and A676G SNPs (D'>0.9 and r2<0.16) (Fig. 1D).

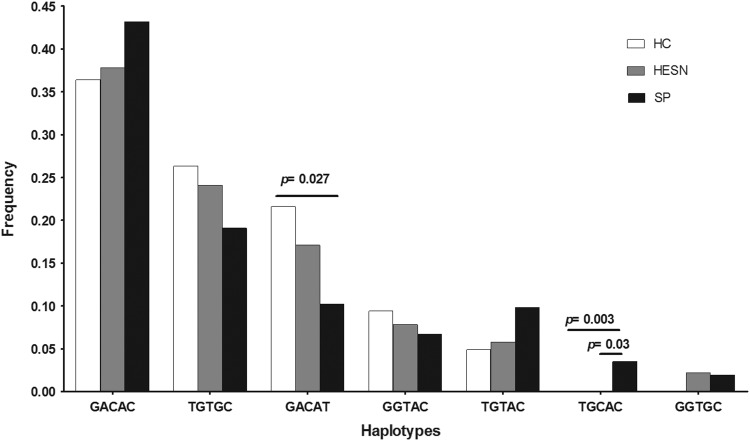

Frequency of haplotypes

The most common haplotypes observed according to the LD results are shown in Fig. 2. GACAC was the most common haplotype in all cohorts, followed by the TGTGC haplotype. The GACAT haplotype was observed at a higher frequency in HCs (21.6%) than in SPs (10%), p=0.027. The TGCAC haplotype was observed only in SPs (3.5%) and was significantly different from other groups (HC, p=0.003 and HESN, p=0.03). However, there were no differences in the frequencies of other haplotypes among SPs, HESNs, and HCs, and no significant association with resistance/susceptibility to HIV-1 infection was noted (Fig. 2). Then, the haplotype frequencies generated when crossing all SNPs (CCR2-V64I, nine SNPs in the CCR5 promoter, A29G, G208T, G303A, T521C, T627C, C630T, A676G, C927T, and A1076C, and the CCR5-Δ32 mutation) showed that the haplotype ATGTTCGCA-CCR2-V-CCR5-WT was the most frequent in HESNs (22.1%), while the haplotype AGATCCACA-CCR2-V-CCR5-WT was the most frequent in HCs (26.2%) and SPs (20.2%). In addition, the haplotype AGATCCATA-CCR2-I-CCR5-WT was more frequent in HCs (19.5%) than in SPs (11%) with p=0.0242; in contrast, the haplotype GGATCCACA-CCR2-V-CCR5-WT was significantly more frequent in SPs (8.9%) than in HCs (3.8%) with p=0.020. Likewise, the haplotype AGATCCACA-CCR2-I-CCR5-WT showed higher frequency in the SPs (14.1%) than in the HCs (3.7%) (p=0.0007; data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Haplotype frequencies by population, which include five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) (G208T, G303A, T627C, A676G, and C927T). The differences between the populations were statistically compared by either the Chi-square or Fisher test. The p<0.05 value was considered statistically significant.

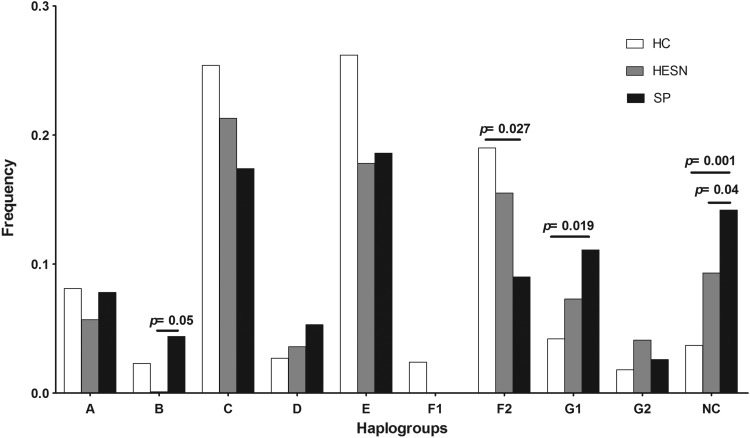

Distribution of the CCR5 human haplogroups

HH frequencies are shown in Fig. 3. HHE was the most frequent haplogroup followed by HHC in the HC and SP groups. In contrast, HHC was the most frequent in HESNs followed by HHE. Comparing the groups, HHF2 was more frequent in HC (19%) than SP (9%), p=0.027. In contrast, SP individuals showed a higher frequency of HHG1 (11.1%) than HCs (4.2%), p=0.019. Likewise, the AGACCAC haplotype, which includes the CCR2-I allele and the CCR5-WT allele (not previously classified as HH),10 was more frequent in SPs (14.2%) than in HCs (3.7%) and HESNs (9%) (p=0.001 and p=0.04, respectively). This haplotype was present in all groups with higher frequency than the B, D, F1, and G2 HH (Fig. 3). HHF1 was found only in the HC group (2.4%), whereas HHB was found in HCs (2.3%) and SPs (4.4%), but not in HESNs. Excitingly, the rarest haplogroups, which have previously not been described, were more common in the HESN group than in the SP and HC groups, with a frequency range of 1.3–2.2% (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

The frequencies of human haplogroup (HH) in HIV-1-exposed, but seronegative individuals (HESN), healthy controls (HC), and seropositive (SP) individuals are shown and the statistical differences among them are indicated. The differences between the populations were statistically compared by either the Chi-square or Fisher test. The p<0.05 value was considered statistically significant. NC, not classified.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed several SNPs in the CCR5 promoter and one SNP in the CCR2 gene in a cohort of serodiscordant couples, in addition to a low-risk uninfected cohort, in order to identify genetic polymorphisms that may be associated with resistance/susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. The analysis showed that CCR5-Δ32 is not a protective factor for this cohort of HESN, which is in accordance with previous reports.26,27 In particular, six SP individuals carrying the Δ32 allele were found; likewise, other authors found HIV-1-positive individuals who were CCR5-Δ32 homozygous, suggesting that CCR5-Δ32-mediated resistance is incomplete.28,29

It was reported that heterozygous SP individuals carrying the CCR2-64I allele exhibit slower progression to AIDS compared with individuals with the CCR2-64V allele.30 However, no clear effects of this allele in protection against HIV-1 infection have been shown. In this study, a significantly higher frequency of HESNs carrying the CCR2-64I allele was observed compared to HCs (OR=1.672), indicating that individuals carrying this allele had a 1.6-fold higher odds of being protected against HIV-1 infection compared to individuals carrying the CCR2-64V allele; likewise, individuals carrying the I/I or V/I genotype had a 2.5-fold higher odds of being protected against HIV-1 compared with individuals with the V/V genotype, indicating that a single copy of this allele (I) is sufficient to induce protection against HIV-1 infection. However, since no differences between HESNs and SPs were found, further studies in other cohorts of HESN are required, before the CCR2-64I mutation can be recognized as a mechanism of protection from HIV-1 infection.

This is the first study evaluating the role of SNPs in the CCR5 promoter and HH in the phenomenon of natural resistance to HIV-1 infection in a South American cohort of discordant couples. We found that individuals carrying the G allele for the A29G SNP had a 3-fold increased risk of being infected by HIV-1. Again, individuals carrying the G/G or G/A genotype had a 2.5-fold increased risk of being infected by HIV-1, indicating that a single copy of the G allele is sufficient to induce susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. Since the frequency of this allele was similar in the HESN and the SP groups, the validity of this association requires further studies.

Remarkably, we observed that the A676G SNP in the SP group does not fit the HWE parameters, and the AA genotype was more frequent in SPs compared to HCs, indicating its association with susceptibility. This result is in agreement with that of Kaur et al., who reported an association between the CCR5-59402A allele (A676) and an increased likelihood of acquisition of HIV-1 and AIDS development in the Asian Indian population.31 Likewise, Kostrikis et al. reported reduced HIV-1 transmission rates for untreated infants who carried the CCR5-59402G allele rather than the CCR5-59402A allele; in addition, they observed an additive protective effect against HIV-1 transmission by the combination of the CCR5-Δ32, CCR5-59353C (627C), and CCR5-59402-G alleles.32

We also found one SNP in the CCR5 promoter that has not been previously reported, the T521C SNP in the -2353 position according to the translation site; the heterozygous genotype was found in one HESN individual. Although the low frequency of this SNP in HESNs might indicate its lack of biological significance, the influence of this SNP in the expression of the CCR5 protein in this individual requires further exploration.

The 927T allele was more frequently present in HCs compared to SPs, OR=0.49; thus, individuals carrying this allele had a 50% lower probability of becoming infected.

Moreover, we found a weak or no LD between the C927T SNP and the G208T, G303A, T627C, and A676G SNPs only in the SP group, supporting the differential distribution of this SNP in the infected population, compared with the HESN and HC groups, and suggesting its association with HIV-1 susceptibility; supporting this finding, the 927T allele has been previously associated with slow AIDS progression and with delay in the decrease in CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts in HIV-1-infected patients.31,33 The implications of these findings require further exploration in this population, since no difference with HESNs was detected.

According to a previous report in a Chinese population,34 the LD analysis revealed a strong LD among at least five SNPs in the CCR5 promoter crossing all groups (G208T, G303A, T627C, A676G, and C927T), indicating that this strong LD is fixed crossing different continental populations.

Interestingly, the TGCAC haplotype containing the 303G allele was observed only in SPs but not in HESNs and HCs; thus, it may have a role in susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in the Colombian population. However, there are no reports supporting this association. Additionally, the GGTAC haplotype containing the 303G allele reported by Xu et al. was associated with susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in the northern Chinese population.34 These haplotypes also contain the 676A allele, which, as mentioned before, has been associated with increased HIV-1 infection and development of AIDS in Asian Indian populations. In contrast, the 303G allele has been associated with lower CCR5 expression in circulating CD14+ monocytes and lower levels of R5 virus replication in vitro.33 These contradictory results could be due to other SNPs in the TGCAC haplotype overcoming the protective effect of the 303G allele. Finally, the GACAT haplotype was more frequent in HC than SP individuals; furthermore, this haplotype contains the 927T allele, which has been associated with slow AIDS progression in SPs and lower probability of becoming infected.31,33

HHC was more frequent than HHE in the HESNs. Previously, Gonzalez et al. reported that white, Asian, and Hispanic American populations exhibited a higher frequency of HHC than HHE, as in our HESN group, but contrary to what was observed in the HC and SP groups. These results suggest that HESNs have a different ethnic background that could be influencing the resistance to HIV-1 infection.18

Recently, higher frequencies of HHC/HHG1 and HHC/HHF2 genotypes were reported in HESN compared to SP individuals, indicating that these haplogroups could be associated with HIV-1 resistance (J. Vega, unpublished observations, 2013). Remarkably, these results also support our finding that HHC might influence the resistance observed in HESNs; indeed, the genotype HHC/HHG2 was previously associated with a protective effect in a similar population.18 Likewise, HHF2 was also previously associated with delayed disease in SP individuals,18 and our results showed a higher frequency of HHF2 in HCs compared with SPs, reinforcing the protective role of HHF2. Interestingly, CCR2-64I is a major driver for HHF2, and as mentioned above, SP individuals carrying this allele exhibit delayed progression to AIDS.30 Here, we report the association of CCR2-64I with protection against HIV-1 infection.

It is also important to mention that HHE, more frequently found in SPs than in HESNs, has been strongly associated with susceptibility and rapid HIV-1 disease progression in previous studies16,19,20; however, we did not find differences with the HC group. Likewise, our results suggest that the higher frequency of HHG1 in SPs is associated with susceptibility. Remarkably, the 29G allele, the major driver for this HH, was associated with increased risk to HIV-1 infection.

The frequency of the NC haplotype was 14.2% in SPs; since it has not been reported before, it could represent a new haplotype found only in the Colombian population, one that might also be associated with susceptibility to HIV infection. Regarding this, we are currently analyzing the HH frequencies in one additional cohort of SP and HESN individuals from Colombia (HESN sexually exposed to HIV) by sequencing and GoldenGate Genotyping Assay (Illumina). Preliminary results indicate that SP and HESN individuals have a similar frequency of 12% and 8% of the NC haplotype, validating the results of the present study. However, these results should be interpreted with caution because our cohort is clearly an example of an admixed population involving predominantly Native American, European, and African components35,36; in addition, it is necessary to include larger cohorts worldwide with a larger sample size in order to avoid chances of spurious association.

Additionally, using the 1,000 genome catalog we obtained the genotype frequencies of CCR5 promoter SNPs and the CCR2-V64I SNP in the general population from Medellín (CLM, http://browser.1000genomes.org). Since the genotype frequency of the CCR5-Δ32 mutation was not reported for this population, we could not infer the frequency of the complete NC haplotype (CCR2-I–AGACCAC–CCR5-WT) (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, we used the SNPs to infer the haplotypes, and we found that the CCR2-I–AGACCAT haplotype had a frequency of 20%, while the CCR2-V–AGACCAC haplotype had a frequency of 9.2% in the CLM population. This result is congruent with the high LD between CCR2-I and 927T (the last position in the haplotype, rs1800024) and the CCR2-V and 927C alleles reported here. However, we also found the recombinant haplotype CCR2-I–AGACCAC with a frequency of 14%, 9%, and 4% in SPs, HESNs, and HCs, respectively. This might be due to a higher frequency of the 927C allele observed in SP individuals (88%) compared to HESNs (82%) and HCs (78%), which was associated with susceptibility in our study.

To define the impact of these SNPs on HIV resistance or susceptibility, it will be necessary to evaluate the surface expression of CCR5 on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from these groups, which could modulate resistance/susceptibility to HIV-1.

It is important to highlight that in contrast to the majority of previous studies, in which HC is the comparison group to evaluate the association of different SNPs with the risk of HIV infection, this study defined the HESN cohort as a high-risk group. Therefore, the results indicating a particular association should have stronger biological significance. Moreover, we did Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison to reduce the possibility of finding significant associations, but increase the probability to finding real genetic associations to resistance or susceptibility to HIV infection.

Additionally, this study was performed with samples obtained from two different Colombian regions, the north coast (Santa Marta) and a central region (Medellín). We are aware that the population mixture is a confounding variable, which could affect the results of association studies, increasing the possibility of obtaining false positives. In fact, it was previously reported that genetic ancestry in Colombia can vary substantially not only across the country but even between regions located relatively close to each other, emphasizing the importance of appropriate population matching when designing case/control studies for human diseases in Latin America.35,36 For this reason, we included HC individuals from both regions with ethnic backgrounds similar to HESN and SP individuals in order to have paired samples, decreasing the possibility of stratification. Indeed, we ruled out stratification bias as a confounding variable.

Taken together, these results suggest that mechanisms responsible for resistance or susceptibility to HIV-1 infection are multifactorial and differ among individuals. Furthermore, multicenter studies including worldwide cohorts of HESN, SP, and HC are required to fully understand the relationship between genetic background and susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. In addition, in vitro HIV-1 infectivity assays are required to validate the association of different SNPs with resistance/susceptibility to HIV-1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Colombian government institute created to support scientific research (COLCIENCIAS) (grant 111549326091) and “Programa Sostenibilidad de los Grupos Inmunovirologia y Genetica Molecular 2013–2014.” Wildeman Zapata and Wbeimar Aguilar-Jimenez are supported by a fellowship from Colciencias, Colombia. The authors thank Anne-Lise Haenni for critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.UNAIDS: Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010

- 2.Piacentini L. Biasin M. Fenizia C, et al. Genetic correlates of protection against HIV infection: The ally within. J Intern Med. 2009;265(1):110–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piacentini L. Fenizia C. Naddeo V, et al. Not just sheer luck! Immune correlates of protection against HIV-1 infection. Vaccine. 2008;26(24):3002–3007. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh P. Kaur G. Sharma G, et al. Immunogenetic basis of HIV-1 infection, transmission and disease progression. Vaccine. 2008;26(24):2966–2980. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulkarni PS. Butera ST. Duerr AC. Resistance to HIV-1 infection: Lessons learned from studies of highly exposed persistently seronegative (HEPS) individuals. AIDS Rev. 2003;5(2):87–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hugonnet S. Mosha F. Todd J, et al. Incidence of HIV infection in stable sexual partnerships: A retrospective cohort study of 1802 couples in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(1):73–80. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200205010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu R. Paxton WA. Choe S, et al. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86(3):367–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rana S. Besson G. Cook DG, et al. Role of CCR5 in infection of primary macrophages and lymphocytes by macrophage-tropic strains of human immunodeficiency virus: Resistance to patient-derived and prototype isolates resulting from the delta ccr5 mutation. J Virol. 1997;71(4):3219–3227. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3219-3227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang DH. Choi BS. Kim SS. The effects of RANTES/CCR5 promoter polymorphisms on HIV disease progression in HIV-infected Koreans. Int J Immunogenet. 2008;35(2):101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2007.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mummidi S. Bamshad M. Ahuja SS, et al. Evolution of human and non-human primate CC chemokine receptor 5 gene and mRNA. Potential roles for haplotype and mRNA diversity, differential haplotype-specific transcriptional activity, and altered transcription factor binding to polymorphic nucleotides in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(25):18946–18961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang J. Shelton B. Makhatadze NJ, et al. Distribution of chemokine receptor CCR2 and CCR5 genotypes and their relative contribution to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) seroconversion, early HIV-1 RNA concentration in plasma, and later disease progression. J Virol. 2002;76(2):662–672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.662-672.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hladik F. Liu H. Speelmon E, et al. Combined effect of CCR5-delta32 heterozygosity and the CCR5 promoter polymorphism -2459 A/G on CCR5 expression and resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission. J Virol. 2005;79(18):11677–11684. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11677-11684.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knudsen TB. Kristiansen TB. Katzenstein TL, et al. Adverse effect of the CCR5 promoter -2459A allele on HIV-1 disease progression. J Med Virol. 2001;65(3):441–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen BR. Kamwendo D. Blood M, et al. CCR5 haplotypes and mother-to-child HIV transmission in Malawi. PLoS One. 2007;2(9):e838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee B. Doranz BJ. Rana S, et al. Influence of the CCR2-V64I polymorphism on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptor activity and on chemokine receptor function of CCR2b, CCR3, CCR5, and CXCR4. J Virol. 1998;72(9):7450–7458. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7450-7458.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh KK. Barroga CF. Hughes MD, et al. Genetic influence of CCR5, CCR2, and SDF1 variants on human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1)-related disease progression and neurological impairment, in children with symptomatic HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(10):1461–1472. doi: 10.1086/379038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ometto L. Zanchetta M. Mainardi M, et al. Co-receptor usage of HIV-1 primary isolates, viral burden, and CCR5 genotype in mother-to-child HIV-1 transmission. AIDS. 2000;14(12):1721–1729. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200008180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez E. Bamshad M. Sato N, et al. Race-specific HIV-1 disease-modifying effects associated with CCR5 haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(21):12004–12009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Excoffier L. Laval G. Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen L. Li M. Chaowanachan T, et al. CCR5 promoter human haplogroups associated with HIV-1 disease progression in Thai injection drug users. AIDS. 2004;18(9):1327–1333. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zapata W. Rodriguez B. Weber J, et al. Increased levels of human beta-defensins mRNA in sexually HIV-1 exposed but uninfected individuals. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6(6):531–538. doi: 10.2174/157016208786501463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaz FJ. Vega JA. Patino PJ, et al. Frequency of CCR5 delta-32 mutation in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seropositive and HIV-exposed seronegative individuals and in general population of Medellin, Colombia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95(2):237–242. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762000000200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hersberger M. Marti-Jaun J. Hanseler E, et al. Rapid detection of the CCR2-V64I, CCR5-A59029G and SDF1-G801A polymorphisms by tetra-primer PCR. Clin Biochem. 2002;35(5):399–403. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(02)00333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett JC. Fry B. Maller J, et al. Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purcell S. Todd-Brown K. Thomas L, et al. PLINK: A toolset for whole-genome association, population-based linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rugeles MT. Solano F. Diaz FJ, et al. Molecular characterization of the CCR 5 gene in seronegative individuals exposed to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) J Clin Virol. 2002;23(3):161–169. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Y. Paxton WA. Wolinsky SM, et al. The role of a mutant CCR5 allele in HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Nat Med. 1996;2(11):1240–1243. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh DY. Jessen H. Kucherer C, et al. CCR5Delta32 genotypes in a German HIV-1 seroconverter cohort and report of HIV-1 infection in a CCR5Delta32 homozygous individual. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheppard HW. Celum C. Michael NL, et al. HIV-1 infection in individuals with the CCR5-delta32/delta32 genotype: Acquisition of syncytium-inducing virus at seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29(3):307–313. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200203010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith MW. Dean M. Carrington M, et al. Contrasting genetic influence of CCR2 and CCR5 variants on HIV-1 infection and disease progression. Hemophilia Growth and Development Study (HGDS), Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study (MHCS), San Francisco City Cohort (SFCC), ALIVE Study. Science. 1997;277(5328):959–965. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaur G. Singh P. Rapthap CC, et al. Polymorphism in the CCR5 gene promoter and HIV-1 infection in North Indians. Hum Immunol. 2007;68(5):454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kostrikis LG. Neumann AU. Thomson B, et al. A polymorphism in the regulatory region of the CC-chemokine receptor 5 gene influences perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to African-American infants. J Virol. 1999;73(12):10264–10271. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10264-10271.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salkowitz JR. Bruse SE. Meyerson H, et al. CCR5 promoter polymorphism determines macrophage CCR5 density and magnitude of HIV-1 propagation in vitro. Clin Immunol. 2003;108(3):234–240. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L. Qiao Y. Zhang X, et al. A haplotype in the CCR5 gene promoter was associated with the susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in a northern Chinese population. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(1):327–332. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bedoya G. Montoya P. Garcia J, et al. Admixture dynamics in Hispanics: A shift in the nuclear genetic ancestry of a South American population isolate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(19):7234–7239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508716103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rojas W. Parra MV. Campo O, et al. Genetic make up and structure of Colombian populations by means of uniparental and biparental DNA markers. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;143(1):13–20. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.