Abstract

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare, benign disorder in children that usually presents with rectal bleeding, constipation, mucous discharge, prolonged straining, tenesmus, lower abdominal pain, and localized pain in the perineal area. The underlying etiology is not well understood, but it is secondary to ischemic changes and trauma in the rectum associated with paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor and the external anal sphincter muscles; rectal prolapse has also been implicated in the pathogenesis. This syndrome is diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and endoscopic and histological findings, but SRUS often goes unrecognized or is easily confused with other diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, amoebiasis, malignancy, and other causes of rectal bleeding such as a juvenile polyps. SRUS should be suspected in patients experiencing rectal discharge of blood and mucus in addition to previous disorders of evacuation. We herein report six pediatric cases with SRUS.

Keywords: Child, Rectal bleeding, Solitary rectal ulcer

INTRODUCTION

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare benign disorder in children which usually presents with rectal bleeding, constipation, mucous discharge, prolonged straining, tenesmus, lower abdominal pain, and localized pain in the perineal area.1-16 The underlying etiology is not well-understood but secondary to ischemic changes and trauma in the rectum associated with paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor and external anal sphincter muscles and with rectal prolapse have been implicated in the pathogenesis.17-19 The diagnosis of the syndrome is based on clinical symptoms and endoscopic and histological findings.

It often goes unrecognized or easily misdiagnosed with other diseases such as inflammatory bowel diseases, amebiasis, malignancy, and other causes of rectal bleeding such as a juvenile polyp.2,5,9,19,20 SRUS should be suspected in patients with rectal discharge of blood and mucus and previous disorders of evacuation. We report herein six pediatric cases with SRUS for reminding this rare syndrome.

CASE REPORTS

1. Case 1

A 10-year-old boy was referred to our pediatric gastroenterology unit with rectal bleeding. He had had episodes of diarrhea, sometimes bloody, during 10 years. Diarrhea had worsened (bloody and increased in frequency) over the 3 months before admission. His physical examination was unremarkable except for rectal prolapse. He had normal growth and had any evidence of bleeding diathesis, significant anemia, bacterial or parasitic infection, or any other systemic diseases. The laboratory examinations including complete blood count, stool examination for parasites and ova, Clostridium difficile toxin and coagulation profile were normal.

Colonoscopy showed an ulcer 2×2.5 cm in diameter located at 6 o'clock in the rectum. Histopathological examination revealed fibromuscular hyperplasia of the lamina propria. The treatment with mesalazin (5-aminosalicylate [5-ASA]) enema was initiated. The treatment was continued with oral sucralfate for 1 year. He is currently being followed with no treatment and further complaints.

2. Case 2

A 12-year-old boy with hypogammaglobulinemia was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a 1-year history of rectal bleeding. His physical examination was unremarkable except for pallor. He had anemia (hemoglobin [Hb], 10 g/L). Colonoscopy revealed solitary lesion 1×1 cm in diameter located between 6 and 9 o'clock in the rectum. Combined oral and enema treatment with mesalazin was initiated. No improvement was observed in his symptoms and follow-up colonoscopy showed no change in the lesion. In addition to ongoing therapy, steroid enema and treatment for constipation was initiated. He used rectal mesalazin and steroid during 1 year. His symptoms had completely resolved and he is currently being followed with no treatment.

3. Case 3

A 12-year-old boy was referred to our pediatric gastroenterology unit for evaluation of a 6-year history of constipation and bloody stool. His physical and laboratory examinations were normal. Colonoscopy revealed solitary lesion 1×5 cm in diameter located at 5 to 10 cm from the anal verge with circumferential distribution. Combined oral and enema treatment with mesalazin was initiated. Because of the failure to achieve clinical improvement in 6 months, second colonoscopy was performed and revealed no significant endoscopic improvement. Therefore, steroid enema (Entocort enema, Prednol-L ampoule, Mustafa Nevzat, Turkey) was used additionally (once a day for 6 months). He responded well to the treatment and his symptoms completely resolved. He is currently being followed with oral mesalazin (during last 1 year).

4. Case 4

A 14-year-old boy admitted with massive rectal bleeding. He had had abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea (10 to 12 episodes daily) during the last 3 months. His physical examination was normal except for pallor. Initial laboratory examinations revealed only anemia (Hb, 10 g/L). Colonoscopy was performed and revealed a lesion located circumferentially at a mean distance of 5 cm from the anal verge. Histopathological examination, including hyperplasia of lamina propria, mild crypt distortion confirmed the diagnosis of SRUS (Fig. 1). Combined oral and enema treatment with mesalazin (Salofalk, twice daily dosing) was initiated. Rectal steroid and rectal sucralfate (3×5 cc/day) was added. He responded well to the treatment and rectal steroid discontinued after 1 month. The rectal bleeding ceased (once every other day). Stool became soft and frequency decreased to two to three times a day. He is currently being followed with ongoing therapy (rectal sucralfate 2×5 cc/day) for SRUS.

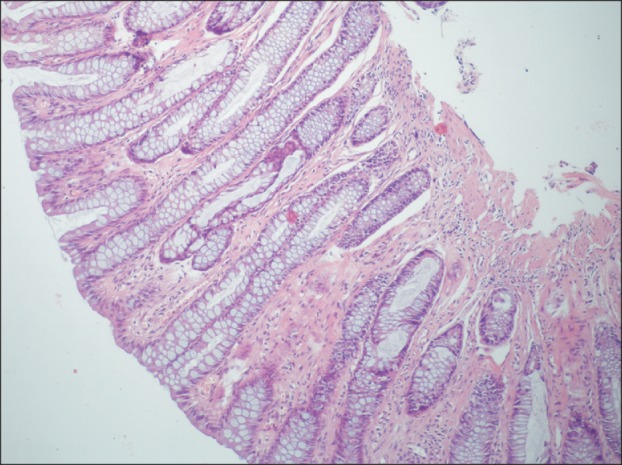

Fig. 1.

Histopathologic examination of the rectal lesion. Mild crypt distortion (H&E stain, ×100).

5. Case 5

A 14-year-old girl was admitted with massive rectal bleeding. She had had constipation and recurrent rectal bleeding during the last 1 year. Despite receiving regular treatment for constipation, the bleeding had not resolved and massive rectal bleeding had occured over the last day before admission. Her physical examination was unremarkable except for pallor. Laboratory examinations revealed only anemia (Hb, 9.7 g/L). Colonoscopy revealed a solitary ulcer 1×2 cm in diameter located between 6 and 9 o'clock in the rectum. Treatment with rectal sucralfate and mesalazin was started. The bleeding ceased. She is currently being followed with ongoing therapy rectal sucralfate (2×5 cc/day).

6. Case 6

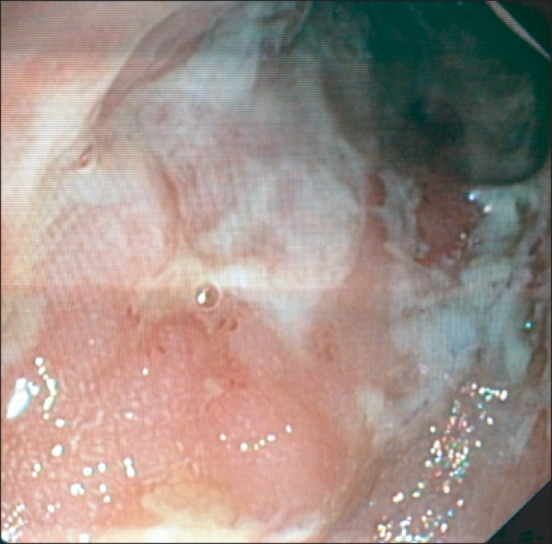

A 16-year-old boy was admitted with rectal bleeding. He had had constipation for 4 years. Colonoscopy revealed multiple, ulcerated polipoid lesions located at 3 to 4 cm from the anal verge (Fig. 2). He responded well to the treatment with mesalazin, sucralfate (3×5 cc) and steroid enema. He is currently being followed with sucralfate enema (2×5 cc) during the last 1 month. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the cases are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Multiple, polypoid ulcerated lesions in the rectum.

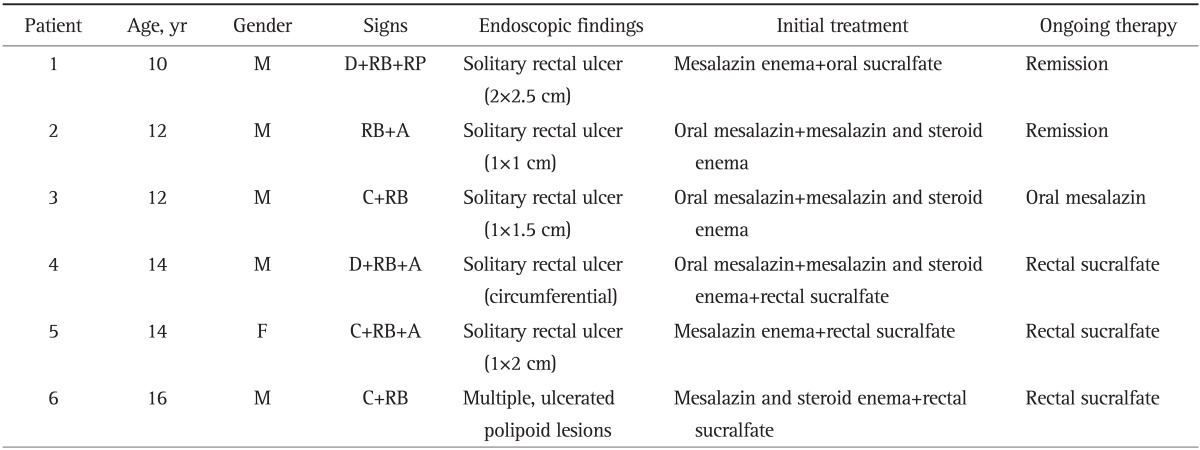

Table 1.

Characteristics, Endoscopic Findings and Management of Patients with Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome

M, male; D, diarrhea; RB, rectal bleeding; RP, rectal prolapse; A, anemia; C, constipation; F, female.

DISCUSSION

SRUS is rare in childhood.7,10,16 Although SRUS usually presents with rectal bleeding, constipation, mucous discharge, prolonged straining, tenesmus, and lower abdominal pain,1-16 some children present with apparent diarrhea and the associated bleeding and abdominal pain may suggest the presence of inflammatory bowel disease.2,4 Two of our cases were presented with diarrhea.

The average time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis is 3.2 years, ranging from 1.2 to 5 years in children, which is shorter than in adult patients (5 years; range, 3 months to 30 years).3,12 It was 4.7 years (range, 0.5 to 10 years) in our patients. It has been reported that 75% to 80% of children with SRUS are boys as similar with our report.3,6,12

The pathophysiology of SRUS is incompletely understood. It is supposed to be due to secondary to ischemia and trauma to the rectal mucosa and paradoxical contraction of pelvic floor.17-19 The excessive straining generates a high intrarectal pressure which pushes the anterior rectal mucosa into the contracting puborectalis muscle resulting in pressure necrosis of rectal mucosa and the anterior rectal mucosa is frequently forced into the closed anal canal causing congestion, edema, and ulceration.21

SRUS is a misnomer as the lesion may be solitary or multiple and different in shape and size (ulcerative, polypoidal/nodular, or erythematous mucosa only).4,19 Macroscopically, SRUS typically appears as shallow ulcerating lesions on a hyperemic surrounding mucosa, most often located on the anterior wall of the rectum at 5 to 10 cm from the anal verge, ranging from 0.5 to 4 cm in diameter but usually are 1 to 1.5 cm in diameter.12,19 The polypoid variant is very rare among the cases reported in children.10,12,13

Histological examination is the gold standard for establishing the diagnosis of SRUS. The histological criteria for diagnosis include a thickened mucosal layer with distortion of the crypt architecture and fibromuscular obliteration which means that the lamina propria is replaced with smooth muscle and collagen leading to hypertrophy and disorganisation of the muscularis mucosa.22 Histological examination of biopsy material was done in all of our patients to confirm the diagnosis of SRUS.

Anemia is not consistently present in SRUS.5,7-11,15,16 A prolonged period of misdiagnosis may cause anemia secondary to massive bleeding, but blood transfusion in SRUS is rare.8 Three of our cases had anemia. None of them received blood transfusion.

Rectal prolapse, either occult or overt is well documented in SRUS.6,10,22 One of our patients had rectal prolapse, as previously reported in children with SRUS.8,10,12

Therapeutic experience in children with SRUS, is limited, with variable treatment protocols and clinical outcomes. Current treatment includes bulking agents (lactulose), enemas (steroid and mesalamine), oral 5-ASA, sucralfate, bowel retraining with or without biofeedback, endoscopical steroid injection and surgery (rectopexy, excision of ulcer) in refractory cases not responding to conservative treatments. Local sucralfate, sulfasalazine or steroid enemas have been reported to be effective.12,22 Application of sucralfate enema is a suitable initial medical treatment for children with SRUS,12 enemas,12 laxatives,15 and surgical approaches have been used more frequently than biofeedback therapy in most reported pediatric case series. All of our cases were treated with mesalazin enema initially. Three of them also received oral mesalazin. Only four of them in whom no clinical improvement was achieved, needed steroid enema in addition to mesalazin and sucralfate. Three patients received rectal sucralfate and one patient oral mesalazin as ongoing therapy.

Our patients were routinely followed-up and assessed for further bleeding. Three of the patients with anemia treated with oral iron supplements. Repeat endoscopies were not routinely carried out unless patients had persistent symptoms, particularly bleeding.

In conclusion, physicians must have a high index of suspicion for SRUS in patients who present with rectal discharge of blood and mucus and previous disorders of evacuation or in whom clinical improvement is not achieved with conservative treatments given. It is mandatory to take biopsy specimens from the involved area to confirm the diagnosis and to exclude other diseases.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Keshtgar AS. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:89–92. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f402c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackburn C, McDermott M, Bourke B. Clinical presentation of and outcome for solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:263–265. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31823014c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perito ER, Mileti E, Dalal DH, et al. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:266–270. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318240bba5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Brahim N, Al-Awadhi N, Al-Enezi S, Alsurayei S, Ahmad M. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a clinicopathological study of 13 cases. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:188–192. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.54749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dehghani SM, Malekpour A, Haghighat M. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children: a literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6541–6545. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suresh N, Ganesh R, Sathiyasekaran M. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a case series. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:1059–1061. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin de Carpi J, Vilar P, Varea V. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in childhood: a rare, benign, and probably misdiagnosed cause of rectal bleeding. Report of three cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:534–539. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ertem D, Acar Y, Karaa EK, Pehlivanoglu E. A rare and often unrecognized cause of hematochezia and tenesmus in childhood: solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e79. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pai RR, Mathai AM, Magar DG, Tantry BV. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in childhood. Trop Gastroenterol. 2008;29:177–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godbole P, Botterill I, Newell SJ, Sagar PM, Stringer MD. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2000;45:411–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiriştioğlu I, Balkan E, Kiliç N, Doğruyol H. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children. Turk J Pediatr. 2000;42:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehghani SM, Haghighat M, Imanieh MH, Geramizadeh B. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children: a prospective study of cases from southern Iran. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:93–95. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f1cbb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saadah OI, Al-Hubayshi MS, Ghanem AT. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome presenting as polypoid mass lesions in a young girl. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:332–334. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i8.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong VH, Jalihal A. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: characteristics, outcomes and predictive profiles for persistent bleeding per rectum. Singapore Med J. 2006;47:1063–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueroa-Colon R, Younoszai MK, Mitros FA. Solitary ulcer syndrome of the rectum in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989;8:408–412. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198904000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sondheimer JM, Slagle TA, Bryke CR, Hill RB. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in a teenaged boy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4:835–838. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198510000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackle EJ, Parks TG. The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of rectal prolapse and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;15:985–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutter KR, Riddell RH. The solitary ulcer syndrome of the rectum. Clin Gastroenterol. 1975;4:505–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Church JM, Lavery IC, Oakley JR, Milsom JW. Clinical conundrum of solitary rectal ulcer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:227–234. doi: 10.1007/BF02051012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabra HO, Roberts JP, Variend S, Shawis RN. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children. A report of three cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005;15:213–216. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-821180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turck D, Michaud L. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Walker WA, Goulet OJ, Kleinman RE, Sherman PM, Shneidear BL, Sandarson IR, editors. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. 4th ed. Volume 1. Lewiston: BC Decker; 2004. pp. 266–280. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madigan MR, Morson BC. Solitary ulcer of the rectum. Gut. 1969;10:871–881. doi: 10.1136/gut.10.11.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]