Abstract

Familial juvenile polyposis (FJP) is a rare autosomal dominant hereditary disorder that is characterized by the development of multiple distinct juvenile polyps in the gastrointestinal tract and an increased risk of cancer. Recently, germline mutations, including mutations in the SMAD4, BMPR1A, PTEN and, possibly, ENG genes, have been found in patients with juvenile polyps. We herein report a family with juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS) with a novel germline mutation in the SMAD4 gene. A 21-year-old man presented with rectal bleeding and was found to have multiple polyps in his stomach, small bowel, and colon. His mother had a history of gastrectomy for multiple gastric polyps with anemia and a history of colectomy for colon cancer. A review of the histology of the polyps revealed juvenile polyps in both patients. Subsequently, mutation screening in DNA samples from the patients revealed a germline mutation in the SMAD4 gene. The pair had a novel mutation in exon 10 (stop codon at tyrosine 413). To our knowledge, this mutation has not been previously described. Careful family history collection and genetic screening in JPS patients are needed to identify FJP, and regular surveillance is recommended.

Keywords: Familial juvenile polyposis, Mutation, SMAD4, Exon 10

INTRODUCTION

Juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS) is an uncommon hamartomatous disorder with significant gastrointestinal malignant potential. Approximately one-third of all JPS cases have familial juvenile polyposis (FJP), with a history of similar lesions in at least one first-degree relative.1 FJP is a rare (<1 out of 100,000 people) autosomal dominant disorder with variable penetrance, which is characterized by isolated or multiple juvenile polyps.2 These polyps usually occur in the colon, but they can also be found in the stomach and the small bowel.1-3 JPS is associated with germline mutations in several genes, including SMAD4, BMPR1A, PTEN, and possibly ENG.3-7 About 20% of JPS patients have a germline mutation in SMAD4.6,7 The mechanism by which any of the known JPS mutations cause hamartomas is not yet understood; however, genetic testing is now commonly available for these syndromes. We report a novel germline mutation in exon 10 of the SMAD4 gene in FJP patients.

CASE REPORT

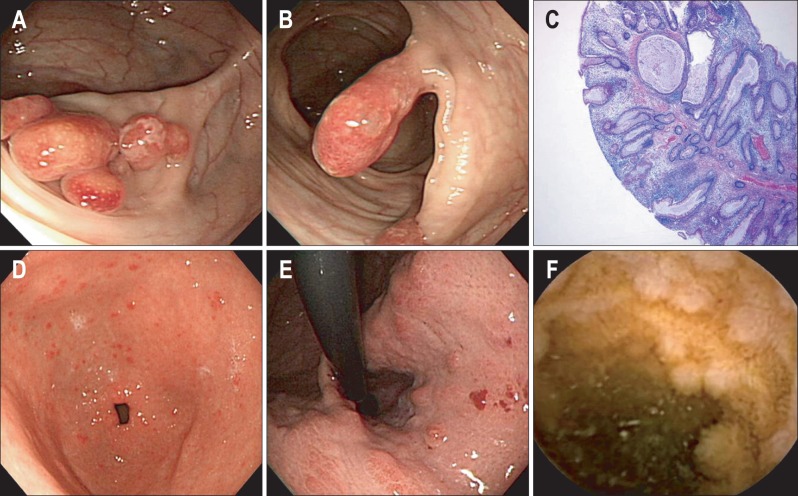

A 21-year-old man presenting rectal bleeding visited our hospital. Based on initial laboratory results, his hemoglobin was mildly decreased of 12.7 g/dL, but no additional abnormalities were found. A colonoscopy indicated multiple colon polyps with hyperemic features (Fig. 1A and B). Histological examination revealed hamartomatous polyps with cystically dilated glands, which were surrounded by stroma and showed prominent inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 1C). Upper endoscopy identified the presence of other lesions and revealed numerous reddish polypoid lesions in the whole stomach (Fig. 1D and E). To confirm small bowel involvement, capsule endoscopy was conducted and it showed numerous polypoid lesions in the jejunum and the ileum (Fig. 1F). Endoscopic removal of gastric and colonic polyps was done. We planned the surveillance with upper endoscopy and colonoscopy every 1 to 2 years, and also planned the evaluation of small bowel every 2 to 3 years.

Fig. 1.

Endoscopy and histological findings of the patient. (A, B) Multiple polyps with a lobulated and pedunculated appearance on colonoscopy. (C) Abundance of edematous lamina propriawith inflammatory cells and cystically dilated glands in resected tissue obtained from colonoscopic polypectomy (H&E stain, ×40). (D, E) Multiple reddish polyps with smooth surfaces in the gastric antrum and cardia on upper endoscopy. (F) Small (approximately 5 mm), sessile or pedunculated polyps in the small bowel on capsule endoscopy.

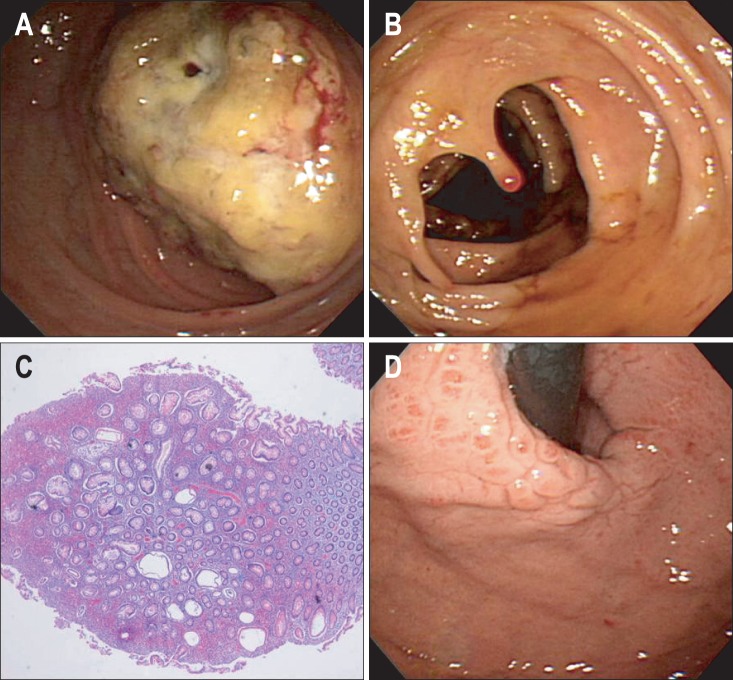

The patient's 47-year-old mother had a history of subtotal gastrectomy due to gastric polyposis with anemia 15 years earlier. She had also undergone a right hemicolectomy because of ascending colon cancer 2 years previously. A colonoscopy performed during that time indicated a pedunculated polyp, which is similar to the type of polyp found in her son (Fig. 2A and B). The histological analysis of the polyps showed hamartomatous features that were consistent with juvenile polyposis (Fig. 2C) Upper endoscopy revealed multiple erythematous polyps in the stomach including cardia which are similar to her son (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic and histological findings of the patient's mother. (A) A fungating mass with an obstruction of the ascending colon observed on colonoscopy. (B) A pedunculated polyp similar to the polyp that was detected in the patient (her son) observed on colonoscopy. (C) A juvenile colonic polyp showing dilated cystic crypts and abundant inflamed lamina propria (H&E stain, ×40). (D) Multiple polyps with smooth surfaces in the cardia similar to those detected in the patient observed on upper endoscopy.

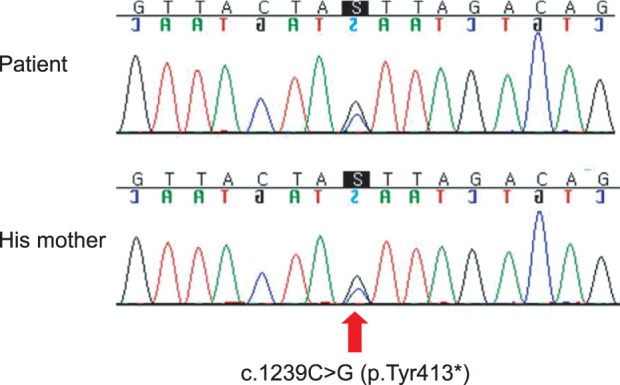

Given the clinicopathological findings and the family history, the diagnosis was FJP. Subsequently, written informed consent was obtained from both patients to perform genetic testing, and screening was performed to determine the presence of a germline mutation in the SMAD4, PTEN, and ENG genes in both patients. All coding exons and the flanking intronic regions of the SMAD4, PTEN, and ENG genes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction on a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using primer pairs designed by the authors. Direct sequencing was performed using the same primers on the ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems). The sequences were analyzed using the Sequencher program (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and compared with the reference sequence. The direct sequencing analysis revealed a novel nonsense mutation in the SMAD4 gene in both the mother and the son. The mutation, a C to G transition at position 1239 in exon 10, resulted in premature stop codon at tyrosine 413 (p.Tyr413*) (Fig. 3). To our knowledge, this mutation has not been described previously. The mutation was not detected in the PTEN and ENG genes.

Fig. 3.

Novel nonsense mutation in the SMAD4 gene detected by direct sequencing analysis of both the patient and his mother. The mutation, a C to G transition at position 1239 in exon 10, resulted in a premature stop codon at tyrosine 413 (p.Tyr413*).

DISCUSSION

JPS is a rare form of the hereditary polyposis syndrome and is generally diagnosed using one or more of the following accepted clinical criteria:8 more than five juvenile polyps in the colorectum, juvenile polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract, and any number of juvenile polyps in conjunction with a family history of juvenile polyposis. The disease usually presents with rectal bleeding and/or anemia in about two-thirds of cases. Less common presentations include rectal prolapse of polyps, abdominal pain, or intestinal obstruction.2,3 Juvenile polyposis is associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal cancer. A recent cancer risk analysis calculated a cumulative lifetime risk for colorectal cancer in JPS of 38.7%.9 In addition, several cases of stomach, duodenal, and pancreatic cancer in patients with JPS have been described in the literature.2 Cancer is thought to arise from a dysplastic change within the hamartomas.3 The risk of developing dysplasia or adenocarcinoma was greatest in patients who had at least three juvenile polyps or a family history of juvenile polyps.10

Macroscopically, juvenile polyps vary in size from 5 to 50 mm, and they typically have a spherical, lobulated, and pedunculated appearance, with surface erosion.1,11 Microscopically, a juvenile polyp is characterized by an abundance of edematous lamina propria with inflammatory cells and cystically dilated glands, which are lined by cuboidal to columnar epithelium with reactive changes.1,11 Mutations in genes related to the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/SMAD pathway have been linked to the development of JPS. The SMAD4 gene is located on chromosome 18q21.1 and encodes a cytoplasmic mediator of the TGF-β signaling pathway, which regulates a variety of biological processes, such as cell proliferation and immune modulation.12 Most SMAD4 germline mutations published to date are small insertions/deletions and single base substitutions leading to nonsense, splice-site, or missense mutations.1,11 The most common mutation in SMAD4 is a 4 base deletion in exon 9, which is therefore a mutational hotspot.13,14 Loss of the wild-type SMAD4 which known as a tumor suppressor gene initiates tumorigenesis, the epithelium of JPS polyps is intimately involved in the formation of the hamartoma and its subsequent progression to carcinoma.15 In addition, SMAD4 mutations are associated with a more aggressive gastrointestinal phenotype. They are involved in a higher incidence of colonic adenomas and carcinomas and more frequent upper gastrointestinal polyps and gastric cancer than patients with other mutations, such as the BMPR1A mutation.3,6,16 In the current report, both the patient and his mother affect upper gastrointestinal polyp and developed the colon cancer in his mother.

Evaluation and management of JPS is mainly based on expert opinion. At risk patients or those with a high suspicion of JPS should undergo endoscopic screening of the colon and upper gastrointestinal tract at age 15 or at the time of first symptoms.2,17 If a diagnosis of JPS is made, the entire gastrointestinal tract should be examined for the presence of polyps. Upper endoscopy/enteroscopy, upper gastrointestinal series, or small bowel follow-through have been recommended for use in upper gastrointestinal evaluation.1,17 Capsule endoscopy can be used to detect intestinal polyps. It can identify small-sized polyps in the small intestine beyond the range of standard endoscopy.18 As capsule endoscopy is a safe and well-tolerated procedure, it may appropriately be employed as a baseline investigation in order to identify patients with small-bowel polyps. In our case, capsule endoscopy was conducted and it helps to identify the small bowel involvement of JPS, as well as clarify the characteristics, including the size and shape of polyps.

Genetic testing can be useful for at-risk members of families where germline mutations have been identified. Howe et al.19 suggested that with genetic testing noncarriers may no longer require frequent screening endoscopy, whereas gene carriers can be targeted for close endoscopic surveillance and early intervention to prevent the development of gastrointestinal cancers. Endoscopic examinations of the colon and the upper gastrointestinal tract are recommended every 2 to 3 years in patients with JPS.17 In patients with polyps, endoscopic screening should be performed yearly until the patient is deemed to be polyp free. Patients with mild polyposis can be managed with frequent endoscopic examinations and polypectomy.20 Endoscopic treatment of gastric polyps can be difficult, and patients with symptomatic gastric polyposis (e.g., severe anemia) may need subtotal or total gastrectomy.1,3

In summary, this report describes a new SMAD4 mutation in a FJP family. Careful family history, genetic screening, and endoscopic screening in JPS patients are needed to identify FJP and the risk of malignancy in the gastrointestinal tract, and regular surveillance is recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a research grant from Chungbuk National University in 2012.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Chow E, Macrae F. A review of juvenile polyposis syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1634–1640. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howe JR, Mitros FA, Summers RW. The risk of gastrointestinal carcinoma in familial juvenile polyposis. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:751–756. doi: 10.1007/BF02303487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latchford AR, Neale K, Phillips RK, Clark SK. Juvenile polyposis syndrome: a study of genotype, phenotype, and long-term outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1038–1043. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31826278b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howe JR, Roth S, Ringold JC, et al. Mutations in the SMAD4/DPC4 gene in juvenile polyposis. Science. 1998;280:1086–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howe JR, Bair JL, Sayed MG, et al. Germline mutations of the gene encoding bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A in juvenile polyposis. Nat Genet. 2001;28:184–187. doi: 10.1038/88919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aretz S, Stienen D, Uhlhaas S, et al. High proportion of large genomic deletions and a genotype phenotype update in 80 unrelated families with juvenile polyposis syndrome. J Med Genet. 2007;44:702–709. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.052506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hattem WA, Brosens LA, de Leng WW, et al. Large genomic deletions of SMAD4, BMPR1A and PTEN in juvenile polyposis. Gut. 2008;57:623–627. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.142927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jass JR, Williams CB, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. Juvenile polyposis: a precancerous condition. Histopathology. 1988;13:619–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1988.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosens LA, van Hattem A, Hylind LM, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer in juvenile polyposis. Gut. 2007;56:965–967. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.116913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giardiello FM, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, et al. Colorectal neoplasia in juvenile polyposis or juvenile polyps. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:971–975. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.8.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brosens LA, Langeveld D, van Hattem WA, Giardiello FM, Offerhaus GJ. Juvenile polyposis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4839–4844. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i44.4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyaki M, Kuroki T. Role of Smad4 (DPC4) inactivation in human cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306:799–804. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedl W, Kruse R, Uhlhaas S, et al. Frequent 4-bp deletion in exon 9 of the SMAD4/MADH4 gene in familial juvenile polyposis patients. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;25:403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howe JR, Shellnut J, Wagner B, et al. Common deletion of SMAD4 in juvenile polyposis is a mutational hotspot. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1357–1362. doi: 10.1086/340258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman TJ, Smith JJ, Chen X, et al. Smad4-mediated signaling inhibits intestinal neoplasia by inhibiting expression of beta-catenin. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:562–571. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sayed MG, Ahmed AF, Ringold JR, et al. Germline SMAD4 or BMPR1A mutations and phenotype of juvenile polyposis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:901–906. doi: 10.1007/BF02557528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002) Gut. 2010;59:666–689. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.179804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Postgate AJ, Will OC, Fraser CH, Fitzpatrick A, Phillips RK, Clark SK. Capsule endoscopy for the small bowel in juvenile polyposis syndrome: a case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1001–1004. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howe JR, Ringold JC, Hughes JH, Summers RW. Direct genetic testing for Smad4 mutations in patients at risk for juvenile polyposis. Surgery. 1999;126:162–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott-Conner CE, Hausmann M, Hall TJ, Skelton DS, Anglin BL, Subramony C. Familial juvenile polyposis: patterns of recurrence and implications for surgical management. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:407–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]