Abstract

Background

Economic conditions and drinking norms have been in considerable flux over the past 10 years. Accordingly, research is needed to evaluate both overall trends in alcohol problems during this period and whether changes within racial/ethnic groups have affected racial/ethnic disparities.

Methods

We used 3 cross-sectional waves of National Alcohol Survey data (2000, 2005, and 2010) to examine a) temporal trends in alcohol dependence and consequences overall and by race/ethnicity, and b) the effects of temporal changes on racial/ethnic disparities. Analyses involved bivariate tests and multivariate negative binomial regressions testing the effects of race/ethnicity, survey year, and their interaction on problem measures.

Results

Both women and men overall showed significant increases in dependence symptoms in 2010 (vs. 2000); women also reported increases in alcohol-related consequences in 2010 (vs. 2000). (Problem rates were equivalent across 2005 and 2000.) However, increases in problems were most dramatic among Whites, and dependence symptoms actually decreased among Latinos of both genders in 2010. Consequently, the long-standing disparity in dependence between Latino and White men was substantially reduced in 2010. Post-hoc analyses suggested that changes in drinking norms at least partially drove increased problem rates among Whites.

Conclusions

Results constitute an important contribution to the literature on racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol problems. Findings are not inconsistent with the macroeconomic literature suggesting increases in alcohol problems during economic recession, but the pattern of effects across race/ethnicity and findings regarding norms together suggest, at the least, a revised understanding of how recessions affect drinking patterns and problems.

Keywords: financial strain, unemployment, alcohol, Hispanic, Black, African American, distress

1. Introduction

1.1 Prior Research on Race/ethnicity and Alcohol Problems

Evidence suggests that Latino populations in the U.S., and especially Latino men, have been at elevated risk of alcohol dependence for some time. All known national survey studies spanning 1991–2005 have shown higher rates of current (12-month) and lifetime alcohol dependence among Latinos than Whites, though sometimes nonsignificantly so. These studies include the 1990–2 National Comorbidity Survey Replication study (NCS-R) (Breslau et al., 2006), the 1991–3 National Household Surveys on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) (Kandel et al., 1997), the 1992 National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey (NLAES) (Chartier and Caetano, 2011), the 2001–2 National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (Hasin and Grant, 2004; Smith et al., 2006), and the 2005 National Alcohol Survey (NAS) (Mulia et al., 2009), all of which have defined dependence using scales based on the APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Caetano and Clark (1998a) also reported higher rates of alcohol-related problems, measured using a combined index of dependence symptoms and alcohol-related consequences, among Latinos (vs. Whites) in the 1995 NAS. Results from gender-disaggregated analyses suggest that these differences were driven by men (Caetano and Clark, 1998a; Hasin and Grant, 2004; Kandel et al., 1997). By contrast, Black-White differences in dependence have been mixed, and smaller. The Latino-White disparity in dependence is consistent with studies suggesting elevated rates of alcohol-related liver cirrhosis (Carrion et al., 2011; Yoon et al., 2011) and somewhat higher binge intensity (Naimi et al., 2010; Neff, 1997; Neff et al., 1991; Zemore, 2007) among Latino men.

Nevertheless, research has shown important historical variation in Latino-White disparities in alcohol problems. To point, early trends analyses of the NAS (Caetano and Clark, 1998a, b) showed that both Whites and Blacks actually had higher rates of alcohol problems (again measured using a combined index of dependence symptoms and consequences) than Latinos in 1984. From 1984 to 1995, however, both male and female Latinos reported increases in frequent heavy drinking and alcohol problems, while Whites of both genders showed decreases in the same, leading to a reversal of the former Latino-White disparity. A more recent analysis of trends in DSM-IV dependence across the 1991–2 NLAES and the 2001–2 NESARC (Grant et al., 2004) likewise found that Latinos had higher rates of dependence than Whites in 1991–2. Yet, by 2001–2, this disparity was considerably diminished due to decreases in dependence symptoms among Latinos, though all groups showed some decline in the same. By contrast, disparities in alcohol abuse remained similar, with all groups showing increased prevalence over time and Whites continuing to report higher prevalence than Latinos and Blacks. (See Caetano et al., 2011, for similar results.)

In short, existing trend studies make a clear case that racial/ethnic disparities have been in considerable flux over time. Moreover, changes in racial/ethnic disparities cannot be obviously linked to larger historical trends, such as changing disparities in socioeconomic status.

1.2 The Current Study

Given the complicated course of racial/ethnic disparities, additional work is needed to understand how disparities have changed since the early 2000’s. An analysis of current disparities, and trends in alcohol problems broadly, is particularly timely in light of the severe 2008–9 economic recession, which, although affecting Whites as well as minorities, has had especially devastating effects on Latino and Black populations (Lopez and Cohn, 2011; Taylor et al., 2011) and may be expected to have altered both the prevalence and distribution of alcohol problems. Supporting that point, numerous individual-level studies have associated involuntary unemployment with heavy drinking and alcohol problems; some macro-economic studies likewise report associations between economic downturns and heavy drinking, though findings are mixed (see (Catalano et al., 2011 for a review). Dee (2001) and others have proposed that economic stress may provoke increases in psychological distress, and hence heavier drinking. Researchers have also speculated that drinking norms in the U.S. may be becoming more permissive, due in part to increased awareness of the potential health benefits of drinking, alcohol marketing, and other factors (Kerr et al., in press; Renaud and deLorgeril, 1992)—though changes in norms have not been directly established. Based on this rationale, the current study uses repeated cross-sectional national survey data to a) examine trends in alcohol problems from 2000 to 2010 overall and by race/ethnicity, and b) investigate the effects of temporal changes on racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol problems.

First, however, some caveats. In interpreting racial/ethnic disparities, it should be recognized that disparities in alcohol problems do not necessarily imply correspondent disparities in consumption. Indeed, evidence suggests that Blacks and Latinos experience greater prevalence of problems than Whites at equivalent levels of consumption, for unknown reasons (Herd, 1994; Jones-Webb et al., 1997; Mulia et al., 2009). Further, Latino-White differences may be qualified by Latino ethnicity. Most research suggests that Mexican Americans (and particularly males) are at higher risk for alcohol problems than Central/South Americans and Cubans, and to a lesser extent, Puerto Ricans (Caetano et al., 1998; Vaeth et al., 2009). Latinos are not homogenous, and we account for this in our analyses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Data Source and Sample

The National Alcohol Surveys (NAS) are independent surveys collected every 5 years by the Alcohol Research Group. Data for the current study were pooled from the three most recent waves: 2000, 2005, and 2010. All surveys involved computer-assisted telephone interviews of a national probability sample of U.S. adults 18 years and older, selected via random-digit dialing. Surveys were augmented by oversamples of Blacks, Latinos, and respondents from sparsely populated U.S. states. The 2010 NAS also included a cell sample constituting about 14% of the total (N=1,012). Respondents were interviewed in English or Spanish. Sample sizes were large across the 2000 NAS (N=7,260; 4,905 Whites, 1,361 Blacks, 994 Latinos), 2005 NAS (N=6,631; 3,967 Whites, 1,054 Blacks, 1,610 Latinos) and 2010 NAS (N=7,647; 4,599 Whites, 1,595 Blacks, 1,453 Latinos), for a total N=21,538, including 13,471 Whites, 4,010 Blacks, and 4,057 Latinos. (Respondents identifying as “Other” were dropped.)

Response rates were 58% in 2000, 56% in 2005, and 52% in 2010. These rates are typical of recent U.S. telephone surveys in a time of increasing barriers to random digit dialing (RDD) studies (Midanik and Greenfield, 2003). Further, methodological studies conducted by the Alcohol Research Group investigating the impact of nonresponse in the 1995 and 2000 Surveys have, comparing independent national samples (or “replicates”) with differing response rates, yielded no consistent differences associated with nonresponse. This suggests that nonresponse is unlikely to have biased NAS prevalence rates. For detailed discussion of the NAS methodology, see Clark and Hilton (1991) and Kerr et al. (2004).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Alcohol dependence symptoms

Dependence symptoms were measured using a 13-item scale representing symptoms in each of the 7 domains identified by the APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-4th Edition (DSM-IV, American Psychiatric Association, 1994). For bivariate analyses and consistent with APA procedures, we created a dichotomous variable indicating at least one symptom in 3 or more domains (vs. fewer/none) over the past 12 months. For inferential analyses, we used the continuous count of criteria endorsed. Items have been extensively validated (Caetano and Tam, 1995).

2.2.2 Drinking consequences

Drinking consequences in the past 12 months were captured by a 15-item scale assessing problems while or because of drinking across 5 domains: social (4 items), legal (3 items), workplace (3 items), health (3 items), and injuries and accidents (2 items). Responses were yes/no. Again, for preliminary analyses, we created a dichotomous variable indicating 2+ consequences (vs. fewer/none), consistent with prior studies on this variable (Cherpitel, 2002; Greenfield et al., 2006; Midanik and Greenfield, 2000), while for inferential analyses, we used the continuous count. These items have been used in the NAS for almost 40 years (Cahalan, 1970), and in prior research, alphas for all subscales ranged from .74–.87, excepting health (Midanik and Greenfield, 2000).

2.2.3 Psychological distress

Distress (used in post-hoc analyses) was measured using an 8-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). Items assess past-week frequency of feelings of distress (e.g., feeling “depressed,” “lonely,” and “bothered by things that don’t usually bother me”), and are highly correlated with the full scale (r=.93, based on 1995 NAS).

2.2.4 Drinking norms

Norms (also used in post-hoc analyses) were measured using 4 items assessing how much drinking is acceptable (“no drinking,” “1 or 2 drinks,” “enough to feel the effects but not get drunk,” or “getting drunk is sometimes all right”) for a man at a bar with friends, for a woman at a bar with friends, at a party at someone else’s home, and with friends at home (Greenfield and Room, 1997) (α=.92). Responses were averaged.

2.2.5 Demographic variables

Demographic variables included racial/ethnic self-identification (White/Caucasian, Black/African American, or Latino/Hispanic), gender (male or female), age (continuous), marital status (married or living as married; separated, widowed, or divorced; or never married), employment status (employed full- or part-time; unemployed; or not in the workforce), annual household income in 2005 dollars ($0–$20,000; $20,001–$40,000; $40,001–$70,000; $70,001 or more; or missing), and education (less than high school; high school graduate; some college; or college degree or higher).

2.3 Analysis

Descriptive, bivariate analyses were conducted to explore racial/ethnic differences in 3+ dependence symptoms and 2+ alcohol-related consequences within survey year. Core analyses were hierarchical, negative binomial regressions modeling counts of dependence symptoms and consequences as a function of race/ethnicity (Black and Latino vs. White), survey year (2005 and 2010 vs. 2000), and interactions between race/ethnicity and survey year, first alone, and subsequently with covariates, to determine whether demographic differences could explain survey effects. Analyses were conducted among men and women separately because preliminary analyses suggested that survey and race effects were not equivalent across gender (see Tables 1 and 2); models including 3-way interactions (i.e., race/ethnicity by survey by gender) were not deemed feasible given model requirements and interpretational issues. Additional analyses were conducted to determine whether changes in psychological distress and/or drinking norms could help explain the temporal trends. Analyses were conducted using Stata (Stata Corp., 2009) to accommodate weights adjusting for sampling and non-response. Survey year was used as the weighting stratum in order to approximate the age, sex and race/ethnicity distributions of the U.S. population at the time each survey was conducted. Weights were normalized to each survey’s sample size, and respondents thus were weighted to represent the average person during the respective year of data collection.

Table 1.

Prevalence of alcohol problems by race/ethnicity within survey year; women only (total N ≥ 11,973)

| Survey Year |

Subgroup | % Alc. Dep. |

Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) Alcohol Dependence |

% 2+ Alc. Consq. |

Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) Alcohol-related Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | White | 1.3 | Ref. | 1.9 | Ref. |

| Black | 1.3 | 1.00 (0.47, 2.12) | 1.2 | 0.61 (0.28, 1.32) | |

| Latinas | 2.0 | 1.55 (0.72, 3.30) | 1.4 | 0.72 (0.30, 1.76) | |

| Total | 1.4 | -- | 1.8 | -- | |

| 2005 | Whites | 1.4 | Ref. | 1.5 | Ref. |

| Blacks | 1.4 | 1.01 (0.40, 2.54) | 1.2 | 0.76 (0.28, 2.12) | |

| Latinas | 2.1 | 1.50 (0.64, 3.53) | 1.4 | 0.93 (0.34, 2.53) | |

| Total | 1.5 | -- | 1.5 | -- | |

| 2010 | Whites | 2.0 | Ref. | 2.3 | Ref. |

| Blacks | 1.7 | 0.84 (0.21, 3.33) | 1.0 | 0.45 (0.13, 1.50) | |

| Latinas | 0.7 | 0.35 (0.06, 1.93) | 1.9 | 0.84 (0.24, 2.98) | |

| Total | 1.8 | -- | 2.0 | -- | |

Notes. No significant differences.

Table 2.

Prevalence of alcohol problems by race/ethnicity within survey year; men only (total N ≥ 9,105)

| Survey Year |

Subgroup | % Alc. Dep. |

Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) Alcohol Dependence |

% 2+ Alc. Consq. |

Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | White | 3.0 | Ref. | 4.9 | Ref. |

| Black | 5.2 | 1.77 (0.99, 3.17)† | 6.3 | 1.30 (0.79, 2.14) | |

| Latinos | 7.1 | 2.46 (1.55, 3.91)*** | 8.0 | 1.69 (1.12, 2.54)* | |

| Total | 3.7 | -- | 5.4 | -- | |

| 2005 | Whites | 2.8 | Ref. | 4.2 | Ref. |

| Blacks | 5.0 | 1.84 (0.96, 3.50)† | 5.7 | 1.38 (0.77, 2.46) | |

| Latinos | 6.5 | 2.42 (1.46, 4.01)*** | 4.5 | 1.07 (0.66, 1.73) | |

| Total | 3.6 | -- | 4.4 | -- | |

| 2010 | Whites | 4.8 | Ref. | 5.3 | Ref. |

| Blacks | 5.3 | 1.12 (0.50, 2.55) | 6.8 | 1.29 (0.60, 2.76) | |

| Latinos | 6.4 | 1.37 (0.68, 2.75) | 8.3 | 1.60 (0.81, 3.17) | |

| Total | 5.1 | -- | 5.9 | -- | |

Notes.

p<.001,

p<.05,

p<.10.

3. Results

3.1 Bivariate Analyses of Trends in Alcohol Problems

Tables 1 and 2 display, for women and men respectively, the prevalence of 3+ dependence symptoms and 2+ consequences by race/ethnicity within survey year, along with the results of logistic regressions testing associations between race/ethnicity and the prevalence of both. Table 1 suggests low rates of alcohol problems among women overall and no significant differences within surveys between Whites, Blacks, and Latinas. Still, the table does imply increases in alcohol dependence among Whites and Blacks in 2010 (vs. earlier surveys), but not Latinas, who show lower rates of dependence in 2010 than previously. Likewise, results suggest minor increases in 2+ consequences in 2010 (vs. earlier surveys), driven mostly by Whites.

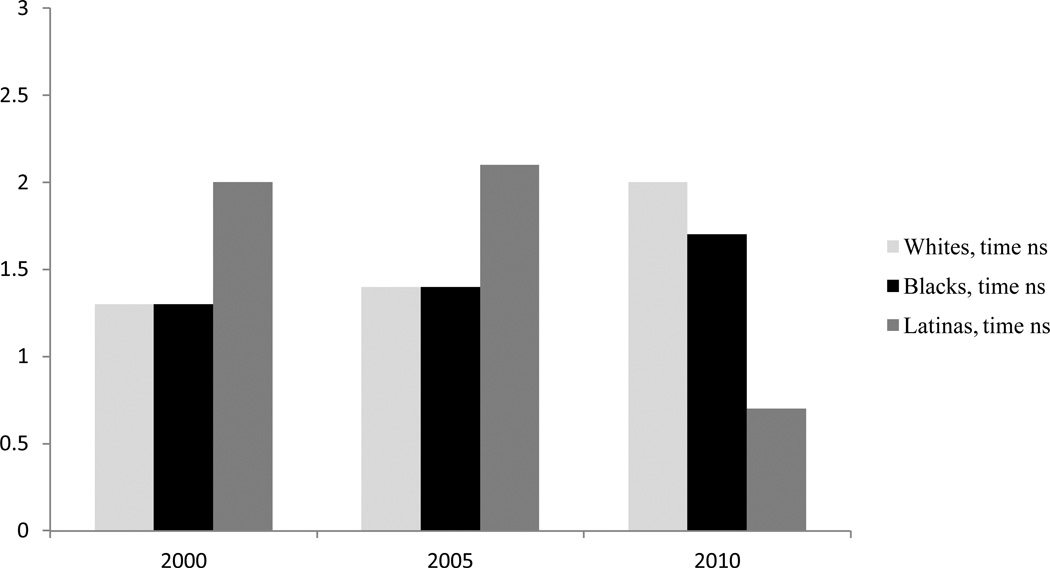

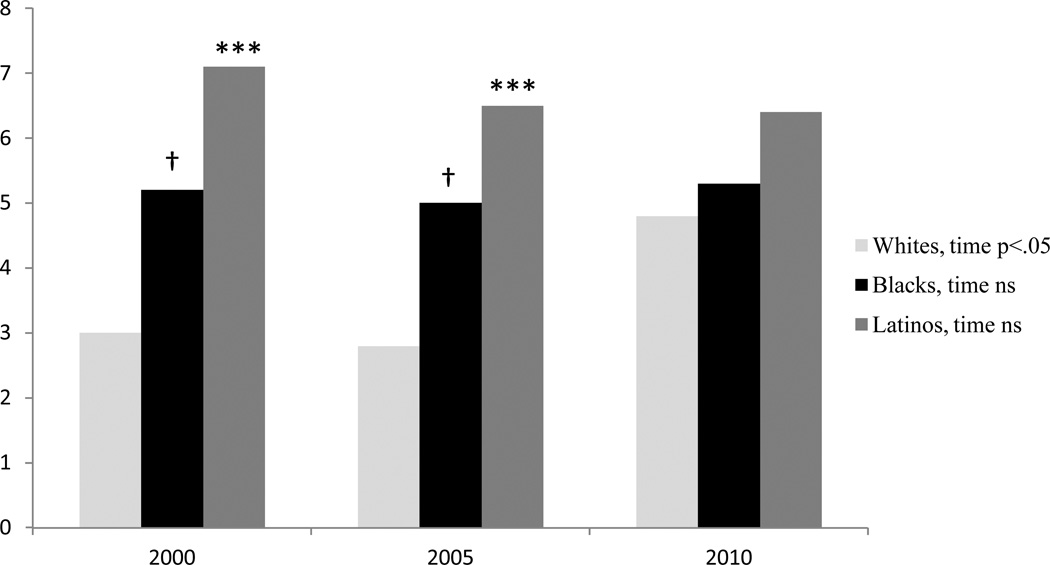

Table 2, addressing men, reveals over twice the rates of alcohol dependence and 2+ consequences among men compared to women in each survey. Also contrary to women, significant racial/ethnic disparities emerge, with Latino men showing higher rates of dependence in both 2000 and 2005, and higher rates of 2+ consequences in 2000, compared to Whites. Paralleling the pattern for women, though, White males show a moderate increase in alcohol dependence in 2010 (vs. earlier surveys), while Black males show a minor increase and Latinos a decrease in the same. Prevalence of 2+ consequences is greatest for all groups in 2010, compared to earlier surveys. Figures 1 and 2 show changes in dependence by race/ethnicity and gender.

Figure 1.

Dependence rates among women over time (y axis is %).

Note. Significance levels tested for (a) Black-White and Latina-White differences within year, indicated above bars (none significant here) and (b) trends over time, indicated in the legend. See Table 1 for associated logistic regression results.

***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05, †p < .10, ns nonsignificant.

Figure 2.

Dependence rates among men over time (y axis is %).

Note. Significance levels tested for (a) Black-White and Latino-White differences within year, indicated above bars and (b) trends over time, indicated in the legend. See Table 1 for associated logistic regression results.

***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05, †p < .10, ns nonsignificant.

3.2 Main Analyses

Results of our negative binomial regressions are shown in Tables 3 and 4 for women and men respectively. Table 3 shows a highly significant increase in dependence symptoms in 2010 (vs. 2000) among White women (and by implication Black women, given the absence of a Black × 2010 interaction). A significant, negative Latina × 2010 interaction implies, conversely, a decline in dependence symptoms among Latinas in 2010 (vs. 2000). Effects are robust in multivariate analyses. Results also suggest an increase in alcohol-related consequences in 2010 (vs. 2000), which is marginally significant in the unadjusted model and significant in the adjusted model. This effect is not qualified by race/ethnicity, but results do suggest fewer consequences among Black (vs. White) women across analyses as well as fewer consequences among Latina (vs. White) women in the multivariate analysis. Dependence symptoms and consequences are equivalent across 2005 and 2000. Among the covariates, both younger age and indicators of living alone (i.e., never married and separated/divorced/widowed, vs. living with a partner) predicted higher rates of both consequences and dependence. Unemployment (vs. employment) was also associated with greater alcohol-related consequences, but women who were out of the workforce had lower rates of alcohol problems than those employed part- or full-time.

Table 3.

Multivariate negative binomial regressions of alcohol problems by race/ethnicity and survey year; women only (N = 11,025).

| Alcohol Dependence Criteria |

Alcohol-related Consequences |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unst. beta |

95% CI | Unst. beta |

95% CI | |

| Unadjusted Models | ||||

| Black (vs. White) | −0.09 | −0.56, 0.38 | −0.37* | −0.73, −0.01 |

| Latina (vs. White) | 0.24 | −0.18, 0.66 | −0.06 | −0.51, 0.40 |

| 2005 (vs. 2000) | 0.09 | −0.20, 0.38 | −0.20 | −0.53, 0.14 |

| 2010 (vs. 2000) | 0.57*** | 0.29, 0.85 | 0.30† | −0.05, 0.65 |

| Black × 2005 | 0.10 | −0.54, 0.75 | --- | --- |

| Black × 2010 | −0.06 | −0.80, 0.67 | --- | --- |

| Latina × 2005 | −0.01 | −0.66, 0.65 | --- | --- |

| Latina × 2010 | −0.82* | −1.53, −0.10 | --- | --- |

| Adjusted Models | ||||

| Black (vs. White) | −0.33 | −0.81, 0.15 | −0.84*** | −1.21, −0.48 |

| Latina (vs. White) | −0.09 | −0.53, 0.35 | −0.45* | −0.86, −0.04 |

| 2005 (vs. 2000) | 0.16 | −0.13, 0.45 | −0.01 | −0.32, 0.30 |

| 2010 (vs. 2000) | 0.72*** | 0.40, 1.04 | 0.45* | 0.10, 0.79 |

| Black × 2005 | −0.03 | −0.68, 0.62 | --- | --- |

| Black × 2010 | −0.23 | −0.93, 0.48 | --- | --- |

| Latina × 2005 | 0.04 | −0.58, 0.66 | --- | --- |

| Latina × 2010 | −0.83* | −1.56, −0.10 | --- | --- |

| Age | −0.05*** | −0.06, −0.04 | −0.05*** | −0.07, −0.05 |

| Never married (vs. partnered) | 0.38* | 0.05, 0.71 | 0.44* | 0.04, 0.84 |

| Sep./wid./divorced (vs. partnered) | 0.59*** | 0.35, 0.83 | 0.41* | 0.08, 0.74 |

| Unemployed (vs. employed) | 0.34 | −0.18, 0.85 | 0.55* | 0.05, 1.05 |

| Out of the workforce (vs. employed) | −0.39** | −0.64, −0.13 | −0.47** | −0.81, −0.14 |

| Income $0–20,000 (vs. $70,001+) | 0.17 | −0.18, 0.52 | 0.31 | −0.18, 0.80 |

| Income $20,001–40,000 (vs. $70,001+) | −0.21 | −0.55, 0.13 | −0.10 | −0.59, 0.39 |

| Income $40,001–70,000 (vs. $70,001+) | −0.07 | −0.42, 0.28 | −0.13 | −0.62, 0.35 |

| Income missing (vs. $70,001+) | −0.45* | −0.89, 0.00 | −0.56 | −1.17, 0.05 |

| Lt. HS education (vs. college grad.) | −0.27 | −0.66, 0.13 | 0.27 | −0.25, 0.78 |

| HS education (vs. college grad.) | −0.23 | −0.51, 0.06 | 0.21 | −0.18, 0.60 |

| Some college (vs. college grad.) | −0.01 | −0.28, 0.26 | 0.18 | −0.18, 0.54 |

Notes.

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<.10.

Table 4.

Multivariate negative binomial regressions of alcohol problems by race/ethnicity and survey year; men only (N = 8,567).

| Alcohol Dependence Criteria |

Alcohol-related Consequences |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unst. beta |

95% CI | Unst. beta |

95% CI | |

| Unadjusted Models | ||||

| Black (v. White) | 0.28 | −0.09, 0.64 | 0.30† | −0.03, 0.62 |

| Latino (v. White) | 0.70*** | 0.42, 0.98 | 0.43** | 0.15, 0.70 |

| 2005 (v. 2000) | −0.05 | −0.29, 0.19 | −0.10 | −0.36, 0.15 |

| 2010 (v. 2000) | 0.32* | 0.07, 0.56 | 0.17 | −0.10, 0.43 |

| Black × 2005 | 0.11 | −0.43, 0.66 | --- | --- |

| Black × 2010 | −0.07 | −0.66, 0.51 | --- | --- |

| Latino × 2005 | −0.18 | −0.58, 0.21 | --- | --- |

| Latino × 2010 | −0.41† | −0.88, 0.06 | --- | --- |

| Adjusted Models | ||||

| Black (v. White) | 0.08 | −0.23, 0.49 | 0.04 | −0.28, 0.36 |

| Latino (v. White) | 0.47* | 0.05, 0.89 | −0.02 | −0.46, 0.43 |

| 2005 (v. 2000) | 0.09 | −0.14, 0.32 | 0.08 | −0.16, 0.32 |

| 2010 (v. 2000) | 0.36** | 0.11, 0.62 | 0.20 | −0.10, 0.51 |

| Black × 2005 | 0.29 | −0.33, 0.91 | --- | --- |

| Black × 2010 | −0.48 | −1.09, 0.13 | --- | --- |

| Latino × 2005 | −0.36 | −0.85, 0.13 | --- | --- |

| Latino × 2010 | −0.59† | −1.21, −0.03 | --- | --- |

| Age | −0.05*** | −0.06, −0.04 | −0.05*** | −0.06, −0.04 |

| Never married (vs. partnered) | 0.57*** | 0.30, 0.84 | 0.37* | 0.05, 0.70 |

| Sep./wid./divorced (vs. partnered) | 0.29* | 0.09, 0.50 | 0.23 | −0.05, 0.51 |

| Unemployed (vs. employed) | 0.48** | 0.12, 0.83 | 0.43† | −0.01, 0.87 |

| Out of the workforce (vs. employed) | −0.17 | −0.44, 0.09 | −0.09 | −0.49, 0.32 |

| Income $0–20,000 (vs. $70,001+) | 0.23 | −0.04, 0.50 | 0.18 | −0.16, 0.51 |

| Income $20,001–40,000 (vs. $70,001+) | 0.08 | −0.18, 0.35 | 0.02 | −0.32, 0.36 |

| Income $40,001–70,000 (vs. $70,001+) | 0.04 | −0.23, 0.30 | 0.13 | −0.24, 0.49 |

| Income missing (vs. $70,001+) | −0.29 | −0.65, −0.07 | −0.49* | −0.92, −0.03 |

| Lt. HS education (vs. college grad.) | 0.28† | −0.02, 0.59 | 0.29 | −0.12, 0.71 |

| HS education (vs. college grad.) | 0.12 | −0.12, 0.36 | 0.14 | −0.21, 0.48 |

| Some college (vs. college grad.) | 0.13 | −0.10, 0.36 | −0.05 | −0.38, 0.28 |

Notes.

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<.10.

Table 4 addresses the results for men. Similar to women, the table shows a significant increase in dependence symptoms in 2010 (vs. 2000) among White men that generalizes to Blacks. Also similar to women, a marginally significant (p=.06), negative Latino×2010 interaction reveals that Latinos reported fewer dependence symptoms in 2010 than 2000. The significant “main effect” indicating greater dependence symptoms for Latinos is thus restricted to 2000 and 2005. Results show no effects for survey year on consequences, although effects associate Black and Latino race/ethnicity with more consequences in the unadjusted model (marginally so for Blacks). Similar to women, both younger age and indicators of living alone predicted higher rates of both consequences and dependence. Higher problem rates were also associated with being unemployed (vs. employed).

3.3 Sensitivity Analyses

It seems plausible that the observed declines in dependence among Latinos are attributable to changes in the acculturation level or ethnic composition of this population over time. Although we found that ethnic subgroup was unrelated to alcohol problems among Latinos of either gender, U.S. nativity was positively associated with dependence for women only (p<.001). Accordingly, we conducted a separate multivariate regression among Latinas examining survey effects on alcohol dependence while controlling for nativity, and found that the parameter estimate and confidence interval for 2010 (vs. 2000) were not notably different.

Another question is whether temporal changes were stronger among particular age or socioeconomic status groups, which might have implications for racial/ethnic disparities. To address this question, we ran additional multivariate models on each outcome while incorporating interactions between survey and age, but still disaggregating by gender and including race/ethnicity as a covariate. Analogous methods were applied to examine interactions between survey and indicators of SES (i.e., family income, poverty status, and unemployment). Because these analyses were exploratory, we examined individual interaction terms only after establishing a significant omnibus test. Among the 4 interaction tests involving age, only one was significant: that is, a survey×age interaction (p<.01) suggesting that the increase in dependence from 2000 to 2010 was stronger among older women (b=.03, p<.001). Among the 12 interaction tests involving SES, only one again attained significance: that is, a survey×income interaction (p<.05) suggesting decreases in consequences in 2005 (vs. 2000) among men in the second-lowest (b=−.90, p<.01) and third-lowest (b=−.76, p<.05) income categories only. Thus, results do not suggest that the increases in alcohol problems in 2010 were limited to particular age or SES groups, although older women were perhaps more strongly affected.

3.4 Analyses of Distress and Drinking Norms

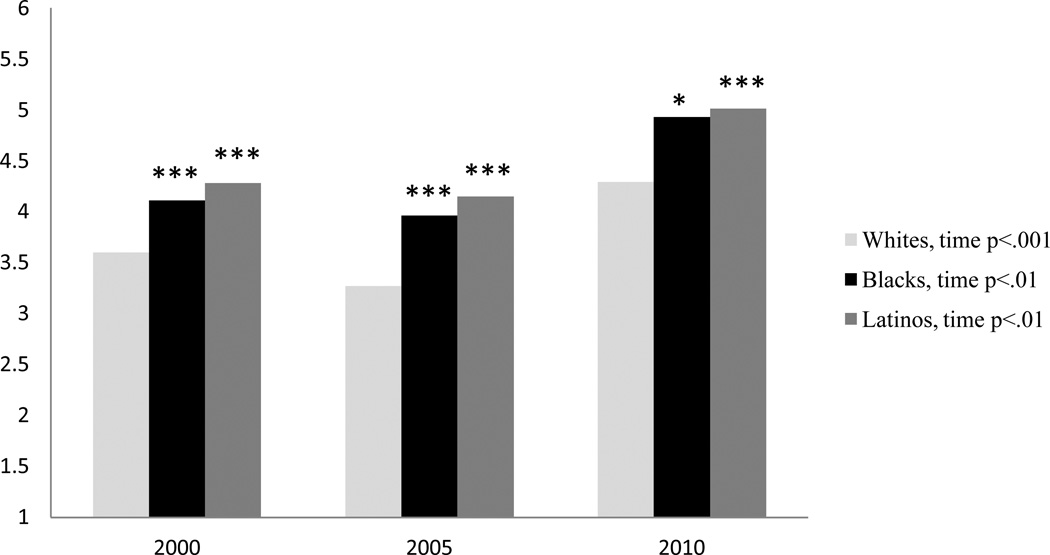

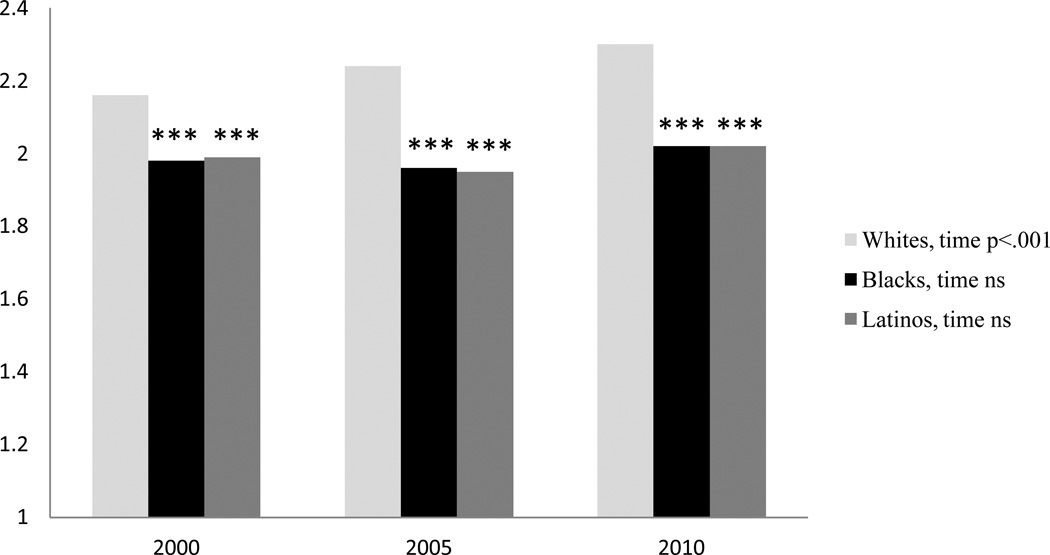

Additional analyses were conducted to determine whether declines in mental health and/or changes in drinking norms might help explain the observed trends. Specifically, we first explored whether distress and norms changed over time. Bivariate tests confirmed that psychological distress differed significantly across survey, with the highest levels reported in 2010, followed by 2000 and then 2005. This pattern held for Whites, Blacks, and Latinos separately (all p’s<.01). Meanwhile, norms became increasingly permissive, in linear fashion, across 2000, 2005, and 2010; unlike distress, however, changes were significant for Whites (p<.001) but not Blacks or Latinos (p’s>.25, see Figures 3 and 4). Next, we reran the multivariate negative binomial regressions displayed in Tables 3 and 4, but now controlling for distress and norms (separately; not shown). Results for distress were inconsistent with mediation: Both survey effects and race × survey interactions were essentially unchanged in models controlling for distress, though distress was positively related to problems across analyses (p’s<.001). By contrast, when controlling for norms, the effect for 2010 (vs. 2010) was diminished in the female model for dependence (from .72, p<.001, to .44, p<.01) and nonsignificant in both the female model for consequences (p=.19) and male model for dependence (p=.21). Race × survey interactions remained similar, and norms were significant across equations (p’s<.001). Thus, while distress was elevated in 2010 (vs. 2000), the data suggest that normative changes in favor of drinking are more likely to explain the increases in alcohol problems seen, particularly among Whites, in 2010. Changes in norms among Whites were significant for both genders (p’s<.001).

Figure 3.

Psychological distress over time (y axis is mean; range 1–32).

Note. Significance levels tested for (a) Black-White and Latino-White differences within year, indicated above bars and (b) trends over time, indicated in the legend.

***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05, †p < .10, ns nonsignificant.

Figure 4.

Drinking norms over time (y axis is mean; range 1–4).

Note. Significance levels tested for (a) Black-White and Latino-White differences within year, indicated above bars and (b) trends over time, indicated in the legend.

***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05, †p <.10, ns nonsignificant.

4. Discussion

4.1 Summary

A reasonable observer might expect that, given both the severe 2008–9 recession and speculations that drinking norms are becoming “wetter,” alcohol problems would be elevated in 2010 (vs. 2000). Consistent with this reasoning, results showed elevations in alcohol dependence among women and men of 29% and 38% respectively, as well as significantly greater alcohol-related consequences among women. These increases do not seem to be driven by shifting demographics, as effects were highly robust in analyses controlling for age, marital status, and socioeconomic status (SES). Also, effects were generally consistent across age and SES groups, though the increase in dependence was somewhat stronger among older women. However, temporal trends were qualified by race/ethnicity, with the increases in dependence being driven mostly by Whites, though Black women also showed some increase in dependence between 2000 and 2010.

Analyses suggested a role for increasingly permissive drinking norms (but no role for psychological distress) in explaining the increases in alcohol dependence among Whites of both genders. White culture may be shifting toward a more liberal stance toward alcohol because of increasing awareness of the potential benefits of alcohol consumption, which have been widely promoted by mainstream media (Kerr et al., in press; Renaud and deLorgeril, 1992). Changing views might also be explained by the increased promotion of alcohol: Spending on spirits advertising increased markedly during the period under study, from about $25 million in 2000 to $82 million in 2005 to $150 million in 2009 (Adams Beverage Group, 2005; The Beverage Information Group, 2010). A related issue is that the affordability of alcohol has increased since 2000, due to the decline in the real value of alcohol taxes (Xu and Chaloupka, 2011). Although we could not address affordability in the current study, this change may have further contributed to the escalation in problems either independently or by exacerbating the effect of changing norms on drinking behavior.

It is noteworthy that drinking norms became increasingly permissive for both White males and White females across 2000–2010, with men if anything showing greater change, and that men and women showed parallel increases in dependence. Also, as noted, we found no evidence that increases in dependence were stronger among younger (vs. older) women—rather, the reverse. These results are inconsistent with the conclusions of a recent review suggesting a temporal narrowing of the gender gap for heavy drinking and alcohol disorders driven by younger women (Keyes et al., 2011). However, additional analyses from our team (Kerr et al., under review) have shown increases in alcohol consumption between 2000 and 2010 that were more robust and larger in magnitude for women than men, which may suggest gender convergence for some outcomes. It is also notable that, compared to Whites, Blacks and Latinos showed consistently higher levels of psychological distress and less favorable drinking norms, suggesting countervailing influences on drinking behavior (i.e., greater stress, yet less social support for drinking).

Our data argue against a simple causal chain whereby stresses associated with the 2008–9 recession negatively affected mental health, leading to increased alcohol problems. All racial/ethnic groups showed increases in distress in 2010 (vs. 2000), but distress was associated with alcohol problems independently of the observed changes in prevalence of alcohol problems. Further, while exposure to severe economic loss (such as employment and housing loss) in the U.S. during the recession was substantially greater among Blacks and Latinos than Whites (Lopez and Cohn, 2011; Taylor et al., 2011; Zemore et al., 2013), it was primarily Whites, and not Blacks and Latinos, who showed increases in alcohol problems between 2000 and 2010. It is true that Whites may conversely have been more likely than Blacks and Latinos to experience loss of retirement savings and other investments during the recession, but associations between alcohol problems and these more moderate forms of economic loss appear to be, overall, weak to null (vs. evidence for powerful associations between severe loss and alcohol problems; see Mulia et al., 2013 and Zemore et al., 2013). This again suggests that changing norms were more important than economic stress in driving the observed trends in alcohol problems.

It is not yet clear why changes in drinking norms and alcohol problems failed to generalize to Blacks and Latinos. Indeed, Blacks showed little change in dependence, and dependence decreased among Latinos. Thus, the 2010 survey reveals a substantial reduction in the long-standing disparity between Latino and White men in alcohol dependence: Dependence rates were statistically equivalent across race/ethnicity for both men and women in 2010. It is possible that media and marketing related to alcohol has more effectively reached Whites than Blacks and Latinos. An additional factor that could help explain the decline in dependence among Latinos is the increasingly negative attention that Latino immigrants have received in recent years (Pew Hispanic Center, 2007). Social pressures may have motivated increasingly conservative substance use patterns among Latinos. Latino survey respondents may also be increasingly reluctant to report on sensitive topics as a result of the increased scrutiny.

Additional findings revealed that (in bivariate models) Latino and Black men reported more alcohol-related consequences than White men, though the Black-White difference was only marginally significant, with little change in this disparity over time. Post-hoc analyses (not shown) suggest that the younger age distribution of Blacks and Latinos (vs. Whites), combined with the higher rate of unpartnered status of Blacks, are largely responsible for these disparities. Black women persistently reported fewer alcohol-related consequences than White women, but equivalent levels of dependence.

4.2 Limitations and Final Conclusions

All data are self-report, and motivations to deny alcohol problems could vary by race/ethnicity (Keyes et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2010). Survey response rates were moderate, and sample sizes were not large enough to examine differences by age or SES within racial/ethnic group. Nevertheless, the NAS provide reliable, national estimates of alcohol problems, and the incorporation of cell phone users and data weighting bolster representivity. The study offers a valuable update on racial/ethnic disparities, examined last on data a decade old (Chartier and Caetano, 2011; Grant et al., 2004), and shows significant racial/ethnic differences in temporal trends. Meanwhile, the substantial elevations in alcohol problems overall suggest a need for increasing attention to prevention and treatment strategies nationally.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. William Kerr for his assistance in interpreting the study results. We also thank the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism for funding the current research (R01AA020474 and P50AA005595). Article content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- Adams Beverage Group. Adams Liquor Handbook. Adams, CT, Norwalk, CT: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, Su M, Williams D, Kessler RC. Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a US national sample. Psychol Med. 2006;36:57–86. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Trends in alcohol-related problems among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: 1984–1995. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998a;22:534–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Trends in alcohol consumption patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984–1995. J Stud Alcohol. 1998b;59:659–668. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL, Tam TW. Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities: theory and research. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22:233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Tam TW. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV and ICD-10 alcohol dependence: 1990 U. S. National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D. Problem Drinkers: A national survey. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Inc; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Carrion AF, Ghanta R, Carrasquillo O, Martin P. Chronic liver disease in the Hispanic population of the United States. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2011;9:834-341. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano R, Goldman-Mellor S, Saxton K, Margerison-Zilko C, Subbaraman MS, LeWinn K, Anderson E. The health effects of economic decline. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:431–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier KG, Caetano R. Trends in alcohol services utilization from 1991–1992 to 2001–2002: ethnic group differences in the U. S. population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1485–1497. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ. Screening for alcohol problems in the U.S. general population: comparison of the CAGE, and RAPS4, and RAPS4-QF by gender, ethnicity, and services utilization. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1686–1691. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000036300.26619.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark WB, Hilton ME, editors. Alcohol in America: drinking practices and problems. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dee TS. Alcohol abuse and economic conditions: evidence from repeated cross-sections of individual-level data. Health Econ. 2001;10:257–270. doi: 10.1002/hec.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Nayak MB, Bond J, Ye Y, Midanik LT. Maximum quantity consumed and alcohol-related problems: assessing the most alcohol drunk with two measures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1576–1582. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Room R. Situational norms for drinking and drunkenness: trends in the U.S. adult population: 1979–1990. Addiction. 1997;92:33–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Grant BF. The co-occurrence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse in DSM-IV alcohol dependence: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related conditions on heterogeneity that differ by population subgroup. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:891–896. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. Predicting drinking problems among black and white men: results from a national survey. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:61–71. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb RJ, Hsiao C-Y, Hannan P, Caetano R. Predictors of increases in alcohol-related problems among black and white adults: results from the 1984 and 1992 National Alcohol Surveys. Am J Alc Drug Abuse. 1997;23:281–299. doi: 10.3109/00952999709040947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Chen K, Warner LA, Kessler RC, Grant B. Prevalence and demographic correlates of symptoms of last year dependence on alcohol, nicotine, marijuana and cocaine in the U.S. population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:11–29. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age, period and cohort influences on beer, wine and spirits consumption trends in the US National Surveys. Addiction. 2004;99:1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Ye Y, Bond J, Rehm J. Are the 1976–1985 birth cohorts heavier drinkers? Age-period-cohort analyses of the National Alcohol Surveys 1979–2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04055.x. in press. Addiction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Zemore SE, Mulia N. Trends in alcohol volume from moderate and heavy drinking episodes across White, Black, and Hispanic populations from 2000 to 2010. Emeryville, CA: Alcohol Research Group; 2013. [under review]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Link B, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin D. Stigma and treatment for alcohol disorders in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1364–1372. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Li G, Hasin DS. Birth cohort effects and gender differences in alcohol epidemiology: a review and synthesis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:2101–2112. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MH, Cohn DV. Hispanic Poverty Rate Highest in New Supplemental Census Measure. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. [Accessed: 2011-12-12]. p. 6. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/63t69QjvK]. [Google Scholar]

- Midanik L, Greenfield TK. Trends in social consequences and dependence symptoms in the United States: the National Alcohol Surveys: 1984–1995. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:53–56. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK. Telephone versus in-person interviews for alcohol use: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72:209–\214. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Zemore SE, Murphy RD, Lui H, Catalano R. Economic loss and alcohol consumption and problems during the 2008-9 recession. Emeryville, CA: Alcohol Research Group; 2013. [under review]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Nelson DE, Brewer RD. The intensity of binge alcohol consumption among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff JA. Solitary drinking, social isolation, and escape drinking motivates as predictors of high quantity drinking, among anglo, African American and Mexican American males. Alcohol Alcohol. 1997;32:33–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff JA, Prihoda TJ, Hoppe SK. “Machismo,” self-esteem, education and high maximum drinking among Anglo, black and Mexican-American male drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 1991;52:458–463. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center. 2007 National Survey of Latinos: As illegal immigration heats up, Hispanics feel a chill. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2007. [Accessed: 2012-03-20]. p. 9. [Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/66JAalqZ3]. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Renaud S, deLorgeril M. Wine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart disease. The Lancet. 1992;339:1523–1526. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91277-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Grant BF. Examining perceived alcoholism stigma effect on racial-ethnic disparities in treatment and quality of life among alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:231–236. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Grant BF. Race/ethnic differences in the prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36:987–998. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Fry R, Kochhar R. Wealth Gaps Rise to Record Highs Between Whites, Blacks and Hispanics. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011. [Accessed: 2011-12-12]. p. 37. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/63t9LmInI]. [Google Scholar]

- The Beverage Information Group. Liquor Handbook. Norwalk, CT: The Beverage Handbook; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vaeth PAC, Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Rodriguez LA. Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): alcohol-related problems across Hispanic national groups. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:991–999. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Chaloupka FJ. The effects of prices on alcohol use and its consequences. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34:236–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y-H, Yi H-Y, Thompson PC. Alcohol-related and viral hepatitis C-related cirrhosis mortality among Hispanic subgroups in the United States: 2000–2004. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE. Acculturation and alcohol among Latino adults in the United States: a comprehensive review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1968–1990. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE, Mulia N, Jones-Webb RJ, Lui H, Schmidt L. The 2008–9 recession and alcohol outcomes: Differential exposure and vulnerability for Black and Latino populations. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(1):9–20. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]