Abstract

Introduction

Interdisciplinary collaboration in end-of-life decision-making is challenging. Guidelines developed within the interdisciplinary team may help to clarify, describe, and obtain consensus on standards for end-of-life decision-making and care. The aim of the study was to develop, implement, and evaluate guidelines for withholding and withdrawing therapy in the intensive care unit.

Methods

An intervention study in two Danish intensive care units, evaluated in a pre-post design by a retrospective hospital record review and a questionnaire survey. The hospital record review included 1,665 patients at baseline (12-month review) and 897 patients after the intervention (6-month review). The questionnaire survey included 273 nurses, intensivists, and primary physicians at baseline and 229 post-intervention.

Results

For patients with therapy withdrawn, the median time from admission to first consideration on level of therapy decreased from 1.1 to 0.4 days (p=0.03), and the median time from admission to a withdrawal decision decreased from 3.1 to 1.1 days (p=0.02). Sixty-five percent of the participants who used the guidelines concerning end-of-life decision-making considered them helpful to high or very high extent. No significant changes were found in satisfaction with interdisciplinary collaboration or in withholding or withdrawing decisions being changed or unnecessarily postponed. The healthcare professionals’ perception of the care following withdrawal of therapy increased significantly after implementation of the guidelines.

Conclusions

The study indicates that working with guidelines for withholding and withdrawing therapy in the intensive care unit may facilitate improvements in end-of-life decision-making and patient care, but further studies are needed to provide robust evidence.

Keywords: end-of-life, critical care, guidelines, withholding treatment, collaboration, decision-making

INTRODUCTION

In modern healthcare, evidence-based medicine put into practice via guidelines is the main principle for promoting and ensuring high quality in patient care [1]. Guidelines can be defined as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioners and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances” [2].

Within the intensive care unit (ICU) researchers have examined the impact of working with guidelines in terms on mechanical ventilation [3, 4], sepsis [5], and sedation [6]. In regard to end-of-life care, studies on the effect of guidelines implementation are limited, but related studies are have, among other things, examined the impact of an order form for withdrawal of life support [7], implementation of a strategy including both organisational changes and plans for communication within the care team and with patients and their families [8], and the use of ethics consultations in the ICU [9]. Withholding therapy is defined as a decision not to start or increase a life-sustaining intervention and withdrawing therapy as a decision to actively stop a life-sustaining intervention that is presently being given [10]. End-of-life practice varies between countries due to legal, cultural, and religious differences [10,11,12].

Some of the challenges in end-of-life care is connected with the interdisciplinary collaboration, including different views on the patient’s recovery potential [13, 14], communication issues in the interdisciplinary team [15], and a lack of nurse participation in the decision-making process [16, 17].

Guidelines developed within the interdisciplinary team may help to clarify, describe, and obtain consensus on standards for end-of-life decision-making and care, and thereby improve satisfaction with interdisciplinary collaboration and patient care.

Accordingly, the aim of this study was to develop, implement, and evaluate guidelines for withholding and withdrawing therapy in the ICU.

METHODS

The study was conducted in two regional Danish ICUs with 8 and 11 beds, respectively. At baseline end-of-life issues were occasionally discussed in the ICUs but were not a specific focus. The Danish Health Legislation [18] was unclear at some points regarding end-of-life decision making, inducing some uncertainty and differences in practice among healthcare professionals. The interdisciplinary collaboration was generally good, some discrepancies between nurses, intensivists, and primary physicians were experienced when dealing with end-of-life decision making.

This prompted initiation of a study including different subprojects: investigation of baseline status for end-of-life decision-making through a hospital record review [19], interviews with nurses, intensivists, and primary physicians, and a questionnaire survey [20]. Furthermore, three interdisciplinary audits were conducted in which the participants assessed patient cases and discussed quality goals for end-of-life decision-making.

In 2009, the Danish Association of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine published guidelines for the “Ethical considerations on withholding or withdrawing therapy” [21]; these guidelines however are not mandatory for the ICU staff to follow, and as they consist of a 96-page document, they are not useful as instructions in daily practice. Therefore, development of local guidelines for withholding and withdrawing therapy was planned in order to respond to the identified challenges. The guidelines were developed based on national and international literature, the Danish national guidelines [21], and the challenges and suggestions for improvement elucidated at the baseline surveys. The draft went through review phases among nurses, intensivists, primary physicians, and all relevant Heads of Departments; the guidelines were subsequently approved by the Heads of Departments of Anaesthesiology.

The guidelines (please see online supplement for full copy) consisted of the following five sections: A) short background on legal issues regarding end-of-life decision-making; the section was written in cooperation with an attorney from The National Board of Health; B) definitions and principles; C) issues regarding the decision-making process, such as who should be involved and what should be documented; D) agreements and practical advice regarding withholding and withdrawing therapy; E) key recommendations regarding patient, relatives, and staff.

The guidelines were published on the hospitals’ on-line guideline systems (INFO-net) in May 2011, and were presented at staff meetings. E-mail notifications were sent to all nurses and intensivists. The Head of Departments backed the implementation as well as the relevance and necessity of the guidelines.

The effect of implementing guidelines for withholding and withdrawing therapy was evaluated 6 months after implementation through a hospital record review and a questionnaire survey. All patients who died in one of the ICUs or were discharged with treatment withheld or withdrawn between June 1st and November 30th 2011 were included in the hospital record review. Basic characteristics of patients who were discharged from the units with full therapy were also collected. The results were compared to baseline data from patients admitted to the two ICUs in 2008 [19].

The questionnaire related to different aspects of end-of-life practices, including applicability of the guidelines and was almost identical to a baseline questionnaire regarding end-of-life issues in Danish ICUs which was developed and validated in 2010 [20, 22]. Five questions evaluating the guidelines were added. To prevent the questionnaire being too comprehensive, seven general questions about end-of-life issues (not relevant for evaluation of the guidelines) were removed.

The main end-point was the length of stay for patients with therapy withdrawn. With 117 patients at baseline, an expected 58 patients at evaluation, and with a 0.05 and b 0.80, the length of ICU stay should be reduced by 2 days (SD 4.4) to be statistically significant. Data were double-entered into EpiData (version 3.1), and descriptive and statistical analyses were performed using STATA 10.1. For comparing different staff groups, the chi-square test was used for dichotomous and categorical data, and the Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used for non-normally distributed continuous and ordinal data. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for paired analyses.

According to Danish law, the study did not require permission from The Regional Ethics Committee, as confirmed by the Committee. Permission to conduct a hospital record review was granted from The Danish Data Protection Agency and The Danish National Board of Health. Permission to obtain and store code lists of staff for the questionnaire survey was granted from The Danish Data Protection Agency. All Heads of Departments gave permission to their staff to take part in the survey. All participants were informed that participation was voluntary, and that responses were anonymous. Permission to include data from the baseline questionnaire survey [20] and the hospital record review [19] was granted from Springer and Wiley.

RESULTS

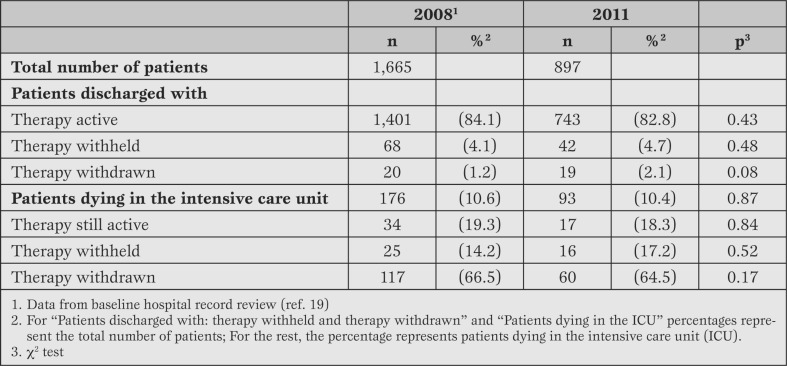

Hospital record review. When comparing pre- and post-intervention data, no differences existed in the percentage of patients who died in the ICU, or in the proportion of patients who died while undergoing therapy, after therapy was withheld, or after therapy was withdrawn (Table 1).

Table 1.

Levels of therapy. Comparison between hospital record reviews at baseline (12 months, 2008) and after guideline implementation (6 months, 2011).

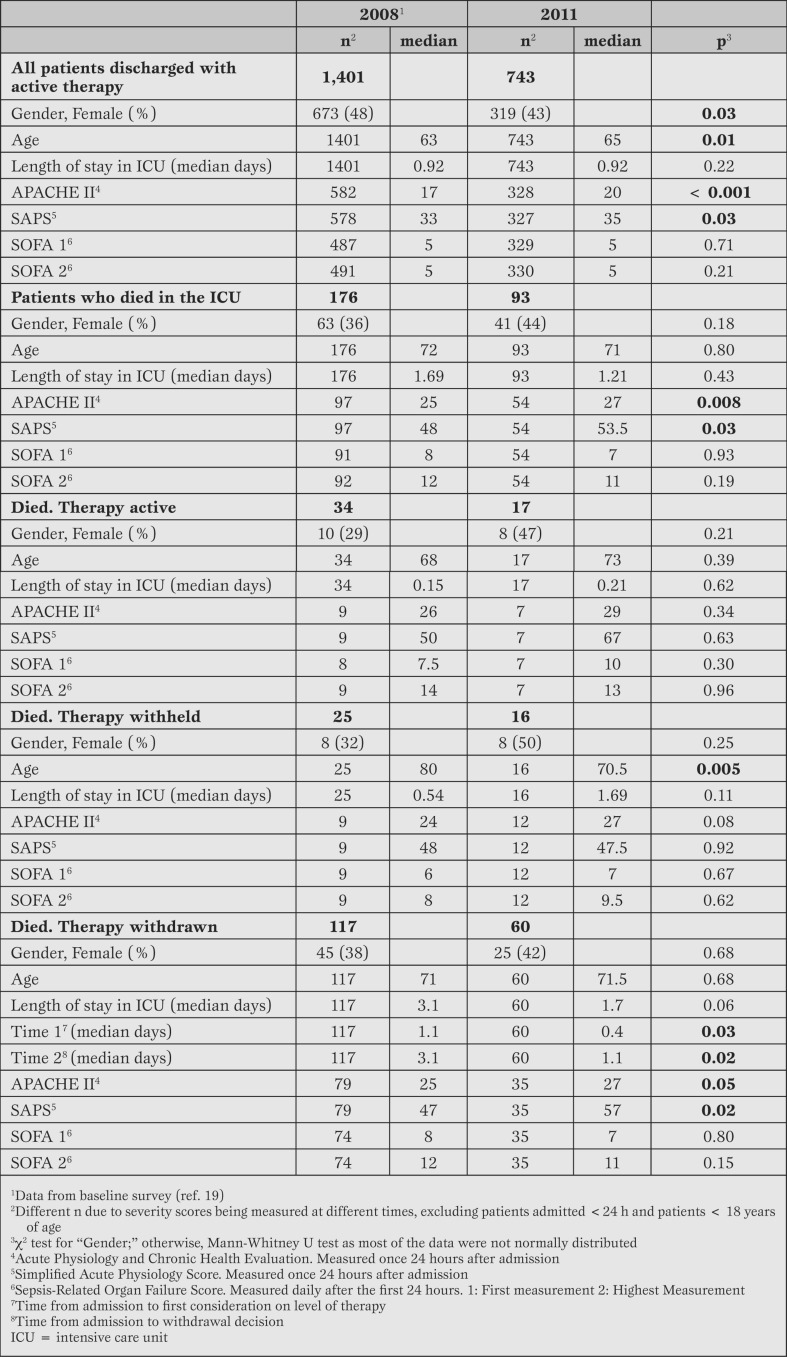

For patients dying after therapy withdrawal, median length of stay from admission to first consideration on level of therapy decreased from 1.1 to 0.4 days and time from admission to withdrawal decision decreased from 3.1 to 1.1 days. A non-significant decrease was found in total length of stay (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of background characteristics, lengths of stay, and severity scores between hospital record review at baseline (2008) and after guideline implementation (2011).

For patients in whom therapy was withdrawn, no differences existed in gender or age, but the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) scores were higher (Table 2).

When comparing all patients who died in the ICU in the two periods, there were no significant differences with respect to reasons for admission (p=0.15), number of chronic diseases (p=0.91), or number of organs affected (p=0.19). There was a significant difference regarding the specialities from which the patients were admitted (p=0.002), mainly due to an increase in the number of medical patients (from 32% to 56%) and a decrease in the number of surgical patients (from 30% to 22%). For patients with therapy withdrawn, the same characteristics were observed.

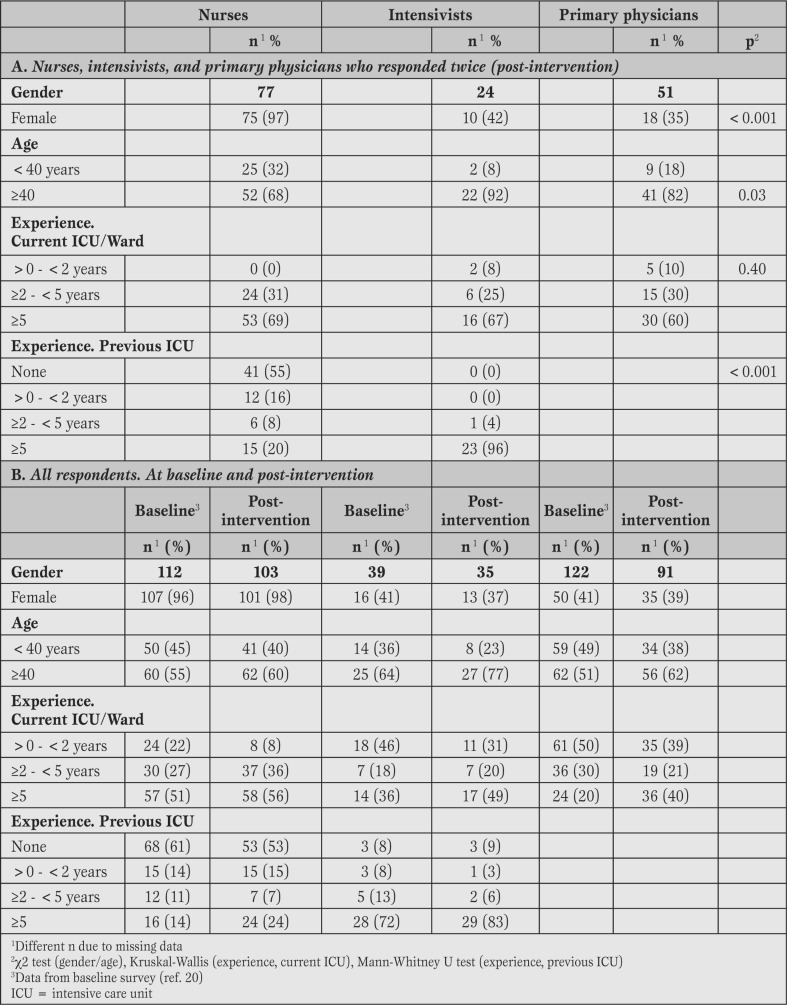

Questionnaire survey. The response rate was 81% (229/281): 84% (103/122) for nurses, 81% (35/43) for intensivists, and 78% (91/116) for primary physicians.

At baseline, the response rate was 88% (273/310) [17]. Of the participants, 66% (152/229) responded both at baseline and after the intervention (75% of the nurses, 69% of the intensivists, and 56% of the primary physicians). Table 3 presents data from all survey responders, but statistical analyses were only conducted for those who responded twice.

Table 3.

Background characteristics: A) Nurses, intensivists, and primary physicians who responded both at baseline and after implementation of guidelines (data from post-intervention time); B) All nurses, intensivists, and primary physicians who responded either at baseline or after implementation of guideline.

For participants who responded twice, there was a significant difference between nurses, intensivists, and primary physicians regarding gender, age and previous experience. The same tendency was found for all responders.

Of the participants, 62% (141/229) had read all or part of the guidelines (76% of the nurses, 83% of the intensivists, and 37% of the primary physicians). In the 6 month period, 62% of the participants were involved in end-of-life decision-making and 38% of these had used the guidelines in connection with the decision-making. Of the participants who had used the guidelines, 65% and 31% considered the guidelines usable to a high/very high extent and some extent, respectively.

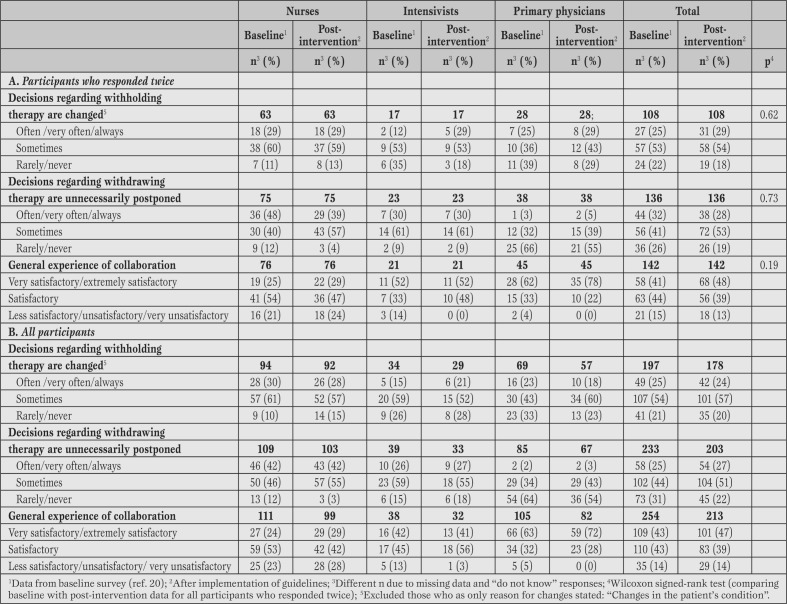

With respect to satisfaction with end-of-life decision-making, 41% of the participants considered interdisciplinary collaboration very or extremely satisfactory at baseline compared to 48% of the participants after implementation (paired analysis) (Table 4). For participants who responded twice, no changes were found in experiences of withholding or withdrawing decisions being changed or unnecessarily postponed (Table 4).

Table 4.

Nurses’, intensivists’, and primary physicians’ experiences of different aspects of end- of-life decision-making (A. Participants who responded twice and B. All participants).

At baseline, 55% of the nurses stated that they very often or always were involved in end-of-life decision-making, and 54% of the intensivists and 39% of the primary physicians stated that nurses very often or always were involved [20]. After implementation of the guidelines, 41% of nurses, 74% of intensivists, and 52% of primary physicians stated that nurses were very often or always involved in the decision-making process.

At baseline, 27% of the participants who responded both at baseline and at post-intervention found the quality of care for patients with therapy withdrawn extremely satisfactory; this was the case for 42% post-intervention (p=0.007). In regard to the quality of care for the patients’ relatives this was the case for 23% and 44%, respectively (p=<0.001).

DISCUSSION

For patients with therapy withdrawn, the median time from admission to first consideration on level of therapy and the median time from admission to a withdrawal decision decreased significantly between baseline and after implementation of the guidelines. No increase in number of patients having therapy withdrawn was found. The study thus suggests that working with guidelines for withholding and withdrawing therapy in the ICU may improve patient care through faster end-of-life decision-making for patients who will not survive intensive care.

Only a small, non-significant increase was found in satisfaction with the interdisciplinary collaboration with end-of-life decision-making. The small increase may be influenced by the fact that at baseline more than 80% of nurses, intensivists, and primary physicians already considered collaboration regarding end-of-life decision-making satisfactory, very satisfactory, or extremely satisfactory [20].

As stated in the guidelines, all relevant healthcare professionals, including nurses, should be part of the decision-making process. However, the percentage of nurses who experienced that they were involved in the decision-making process did not increase from baseline to after implementation of the guidelines. This may also be one of the reasons for the small, non-significant increase in satisfaction with the interdisciplinary collaboration, as lack of involvement in decision-making is associated with lower satisfaction [17, 23].

The strengths of this study include development of guidelines based on extensive participation of involved healthcare professionals, a study mix of data from a questionnaire survey and a hospital record review, and high response rates.

Limitations include the time span between baseline and evaluation and a short implementation period. The decrease in time from admission to withdrawal of therapy may be due to implementation of the guidelines, but also to other factors, e.g. to APACHE II and SAPS scores being higher at time of guideline evaluation and to a higher percentage of medical patients. Length of stay is internationally used as an outcome measure for effects of interventions, also in before-after studies [8]. However, especially in a before-after design the risk of confounders is substantial. The hospital record review on data from 2008 was the first step in the series of projects to examine and improve end-of-life decision-making and care. This entailed the span of 2.5 years between baseline and post-intervention data for hospital record reviews which increases the possibility of other issues than the guidelines having an impact on the changes. The cultural diversity of the individuals involved (patients, family members, and the health care professionals) increases the complexity of end-of-life care [10, 11, 15, 17]; issues that are not easily addressed in guidelines. The guidelines were developed and implemented in two ICUs only; this limits the possibility to generalise the results to other ICUs, but the study may be inspirational for other healthcare professionals wanting to improve end-of-life decision-making, both within and outside the ICUs.

CONCLUSION

This study indicates that working with guidelines for withholding and withdrawing therapy in the ICU may facilitate improvements in end-of-life decision-making and patient care, but further, multicenter studies are needed to provide more robust evidence.

Footnotes

Source of Support The study was funded by the Region of Southern Denmark, Lillebaelt Hospital, Denmark, and the philanthropic foundation TrygFonden, Denmark.

Disclosures None declared.

Cite as: Jensen HI, Ammentorp J, Ørding H. Guidelines for withholding and withdrawing therapy in the ICU: impact on decision-making process and interdisciplinary collaboration. Heart, Lung and Vessels. 2013; 5(3): 158-167.

References

- Timmermans S, Angell A. Evidence-based medicine, clinical uncertainty, and learning to doctor. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42:342–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodek P, Cahill NE, Heyland DK. The relationship between organizational culture and implementation of clinical practice guidelines: a narrative review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2010;34:669–674. doi: 10.1177/0148607110361905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyrnios NA, Connolly A, Wilson MM. et al. Effects of a multifaceted, multidisciplinary, hospital-wide quality improvement program on weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1224–1230. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200206000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood B, Alderdice F, Burns K. et al. Use of weaning protocols for reducing duration of mechanical ventilation in critically ill adult patients: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:7237–7237. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollef MH, Micek ST. Using protocols to improve patient outcomes in the intensive care unit: focus on mechanical ventilation and sepsis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:19–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DL, Proudfoot CW, Cann KF, Walsh T. A systematic review of the impact of sedation practice in the ICU on resource use, costs and patient safety. Crit Care. 2010;14:59–59. doi: 10.1186/cc8956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Crowley L. et al. Evaluation of a standardized order form for the withdrawal of life support in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1141–1148. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000125509.34805.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenot JP, Rigaud JP, Prin S. et al. Impact of an intensive communication strategy on end-of-life practices in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2405-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD. et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1166–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprung CL, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P. et al. End-of-life practices in European intensive care units: the Ethicus Study. JAMA. 2003;290:790–797. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.6.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprung CL, Maia P, Bulow HH. et al. The importance of religious affiliation and culture on end-of-life decisions in European intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1732–1739. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moselli NM, Debernardi F, Piovano F. Forgoing life sustaining treatments: differences and similarities between North America and Europe. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:1177–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen K, Forde R, Nortvedt P. Value choices and considerations when limiting intensive care treatment: a qualitative study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palda VA, Bowman KW, McLean RF, Chapman MG. "Futile" care: do we provide it? Why? A semistructured, Canada-wide survey of intensive care unit doctors and nurses. J Crit Care. 2005;20:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puntillo KA, McAdam JL. Communication between physicians and nurses as a target for improving end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: challenges and opportunities for moving forward. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:332–340. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237047.31376.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbenishty JL, Ganz FD, Lippert A. et al. Nurse involvement in end-of-life decision making: the ETHICUS Study. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:129–132. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2864-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand E, Lemaire F, Regnier B. et al. Discrepancies between perceptions by physicians and nursing staff of intensive care unit end-of-life decisions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1310–1315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-752OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . Health legislation. Law nr. 546 [in Danish]. 2005. [Available at: http://www.retsinformation.dk/ Forms/R0710.aspx?id=130455. Accessed June 6, 2012]

- Jensen HI, Ammentorp J, Ording H. Withholding or withdrawing therapy in Danish regional ICUs: frequency, patient characteristics and decision process. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011;55:344–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen HI, Ammentorp J, Erlandsen M, Ording H. Withholding or withdrawing therapy in intensive care units: an analysis of collaboration among healthcare professionals. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1696–1705. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DASAIM. Danish Association of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Guide. Ethical considerations on withholding or withdrawing therapy. [in Danish]. 2009 [Available at: http://www.regionmidtjylland.dk/files/Region- shuset/Kommunikationsafdelingen/Billeder/2010/03%20 Marts/vejledning_etiske_forhold_ophoer.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen HI, Ammentorp J, Erlandsen M, Ording H. End-of-life practices in Danish ICUs: development and validation of a questionnaire. BMC Anesthesiol. 2012;12:16–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI. et al. Nurse-physician collaboration and satisfaction with the decision-making process in three critical care units. Am J Crit Care. 1997;6:393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]