Abstract

Introduction

Cardiac manifestations of intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage patients include mild electrocardiogram variability, reversible left ventricular dysfunction (Takotsubo), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, ST-elevation myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest, but their clinical relevance is unclear. The aim of the present study was to categorize the relative frequency of different cardiac abnormalities in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage and determine the influence of each abnormality on outcome.

Methods

A retrospective review of 617 consecutive patients who presented with non-traumatic aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage at our institution was performed. A cohort of 87 (14.1%) patients who required concomitantly cardiological evaluation was selected for subgroup univariate and multi-variable analysis of radiographic, clinical and cardiac data.

Results

Cardiac complications included myocardial infarction arrhythmia and congestive heart failure in 47%, 63% and 31% of the patients respectively. The overall mortality of our cohort (23%) was similar to that of national inpatient databases. In our cohort a high World Federation of Neurosurgical Surgeons grading scale and a troponin level >1.0 mcg/L were associated with a 33 times and 10 times higher risk of death respectively.

Conclusions

Among patients suffering from cardiac events at the time of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, those with myocardial infarction and in particular those with a troponin level greater than 1.0 mcg/L had a 10 times increased risk of death.

Keywords: subarachnoid hemorrhage, SAH, myocardial Infarction, MI, arrhythmia, cardiac outcomes, intracranial aneurysm, Takotsubo stress cardiomyopathy

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac abnormalities as a result of subarachnoid intracranial hemorrhage (SAH) have been well described [1,2,3,4]. A variety of electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities have been documented in this patient population with prevalence up to 90% in some studies [3, 5,6,7]. Cardiac manifestations of SAH can range from mild ECG variability, reversible left ventricular dysfunction (Takotsubo), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTMI), ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI) or even cardiac arrest [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Studies also suggest that severity of SAH is associated with likelihood of cardiac changes with concomitant poorer neurological outcomes [15, 16]. Investigators have studied the clinical course and outcomes in SAH patient as it relates to ECG findings, troponin levels and cardiac stunning [2, 17].

Management of patients with aneurysmal SAH continues to be a challenge for neurosurgeons and neuro-intensivists. SAH has both local intracranial effects (hydrocephalus and vasospams) and global systemic effect that can affect pulmonary and cardiovascular system [18, 19]. The cardiac manifestations of SAH are of particular interest because manipulation of blood pressure parameters is routinely used to treat these patients. Initial strict blood pressure control is imperative until the aneurysm can be secured. However, in the setting of vasospam, “triple H” (Hypervolaemia, hypertension, and haemodilution) is used and blood pressure artificially increased. Comprehensive understanding of the cardiovascular complications of SAH is necessary to be able to adequately manage the patient’s medical and neurological needs throughout the hospital stay.

The aim of the present study was to classify the relative frequency of different cardiac abnormalities associated with SAH and to determine the influence of each abnormality on the overall outcome of this subset of patients. In doing so, we established the natural history of these cardiac manifestations in patients with SAH.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review of 617 consecutive patients who presented with non-traumatic aneurysmal SAH at our institution in the period 2002-2006 was performed. Patients identified as having both non-traumatic SAH and cardiology evaluation with diagnostic ECG within 48 hrs of admission were included in this study. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to chart review (University of South Florida IRB #1561). Demographic data, clinical parameters, radiographic findings and laboratory results (troponin I, Creatine KinaseMB) were analyzed. These included age, sex, aneurysm location, World Federation of Neurosurgical Surgeons grading scale (WFNS), distribution of intracranial blood, history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and history of cardiac events/interventions (coronary stenting/angioplasty, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction and history of heart failure).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included age >18, radiographic evidence of non-traumatic SAH and cardiology evaluation with diagnostic ECG within 48 hrs of admission. Conversely, patients with age <18, history of trauma associated with hospital admission, admission diagnosis of arteriovenous malformation/dural arteriovenous fistula or radiographic evidence of subdural/epidural hematoma were excluded.

Radiographic evaluation. SAH was determined with conventional non-contrasted computed tomography (CT). In patients with confirmed SAH, further secondary diagnostic vascular imaging was performed which included CT-angiography and/or cerebral angiography. Secondary vascular imaging was performed within 24 hrs of admission.

Cardiac evaluation. An independent cardiology group evaluated all patients in whom cardiac evaluation was warranted within 48 hrs of admission. Criteria for cardiology evaluation included chest pain, unexplained tachy/bradycardia or arrhythmia on telemetry. Initial diagnostic test included chest x-ray, serial troponin I/Creatine KinaseMB and 12-lead ECG. A cardiologist determined the need for echocardiography based on abnormality of initial diagnostic test and/or high clinical suspicion. The diagnosis of MI was determined by the cardiologist according to international guidelines and defined as a rise of troponin I levels over 0.3 mcg/L, together with evidence of myocardial ischemia (symptoms of ischemia, ECG changes indicative of new ischemia, pathological Q waves, imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality).

Outcome measures. The primary outcome measures included survival, destination of the patients at time of discharge (home, skilled nursing facility/rehabilitation-SNF/Rehab-, death) and general status of the patients (Glasgow Outcome Scale).

Comparison to national inpatient sample. The Healthcare Cost and Utilization (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) was queried using the HCUPnet system (http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov) to generate in-hospital death and discharge statistics for patients with a subarachnoid intracranial hemorrhage (International Classification of Diseases ICD-9 code 430) during the study time period [20]. Comparisons between the national statistics and the study sample were conducted to describe similarities/dissimilarities between SAH patients in general and those with co-occurring cardiac abnormalities.

Statistics. Univariate analysis was performed using Mann-Whitney U (continuous variables), Chi-Square and Fisher Exact test (categorical variables).

Comparisons between national statistics and the study sample were conducted using an exact binomial test. Exploratory multiple variable analyses were performed utilizing step-wise logistic regression to identify potential risk factors for mortality and unfavorable discharge status. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

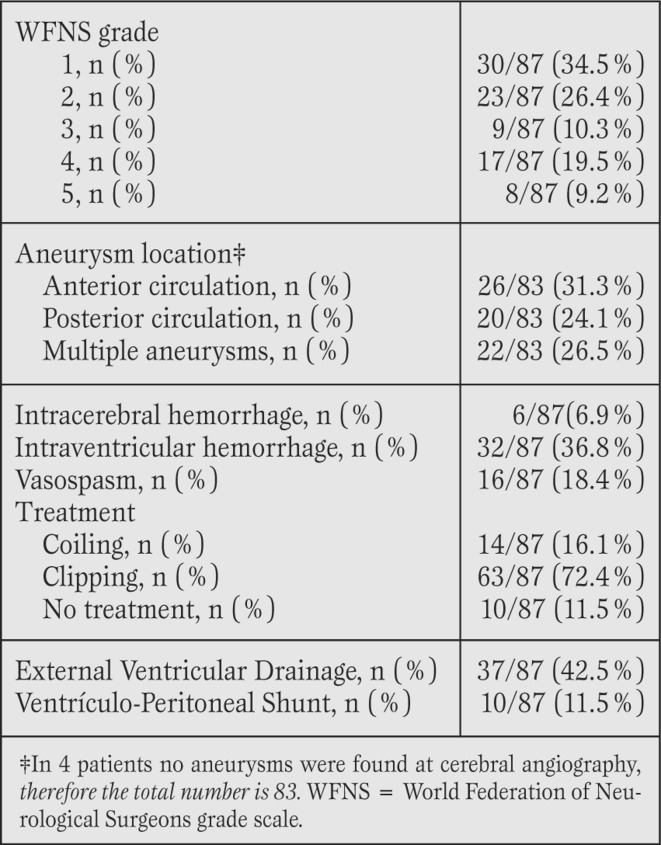

Patient demographics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and cardiac history.

A total of 87/617 (14.1%) of the non-traumatic SAH patients were identified as also having concomitantly required cardiac evaluation. The median age was 65 (range 27-89) and the majority of the patients were female (87.4%).

The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia was 73%, 8% and 11.5%, respectively. History of atrial fibrillation was the most common cardiac arrhythmia, 11.5%.

Twelve patients had history of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). One patient had a history of myocardial infarction and one a history of pacemaker implantation secondary to bradycardia. Two patients (2.3%) had a history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Radiographic and clinical data (Table 2).

Table 2.

Radiographic data.

All patients had radiographic evidence of SAH, with an intracranial aneurysm identified in 83 patients (95.5%). In four patients a causative vascular culprit could not be determined with conventional cerebral angiography hence they were classified as “angiographic negative” SAH (AN-SAH). Radiographically, the distribution of intracranial blood was perimesencephalic which was consistent with diagnosis of AN-SAH. On admission, 62 patients (71.3%) presented with a good clinical grade (WFNS I-III) and 25 patients presented with a poor clinical grade (WFNS IV and V).

The location of the aneurysm was evenly distributed with 28.9% right hemisphere, 33.7% left hemisphere and 37.3% midline aneurysms (anterior communicating artery, pericallosal artery, basilar tip). Clip ligation or endovascular coiling of the aneurysm was undertaken in 77 patients. The aneurysm was not secured in the remaining 10 patients as they remained in WFNS grade V despite aggressive resuscitation and placement of external ventricular drainage.

Cardiac events (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cardiovascular data.

Cardiac complications included MI, arrhythmia and new onset congestive heart failure (CHF) in 47%, 63% and 31% of patients respectively. Among the 41 patients with a new diagnosis of MI, 37 (90.2%) had non-ST elevation infarctions. Tachyarrhythmia occurred in roughly half (50.6%) of the sample with atrial fibrillation as the most common form (28.7%).

ECG changes were observed in 44.8% of the sample. The most frequent ECG changes were T wave inversion (15/87; 17.2%) followed by ST depression (12/87; 13.8%), prolonged QT (9/87; 10.3%) and ST elevation (7/87; 8.0%). Bundle Branch Block was only observed in 4/87 (4.6%) of the group. Patients with concomitant intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) were more likely to have ECG changes compared to those without intraventricular hemorrhage (59% vs 36%, p=0.037).

Cardiac troponin I levels were measured in 67 patients, with elevation noted in 48 patients (71,6%). Seven patients had increases in troponin without clinical evidence of infarction. CK-MB was measured in 64 patients with elevation noted in 43.8% of patients. Six patients underwent a coronary angiogram, with results that included: no coronary disease (3 patients, 50%), mild disease (one patient, 17%) and triple vessels disease (2 patients, 33%; both with history of coronary artery disease with previous PCI).

Finally, echocardiography was performed in 61 patients of which 6.6% exhibited severe depression in myocardial contractility (defined as an ejection fraction [EF] <40%) and 37.7% had an EF>60%. The cardiac outcomes in the 4 patients with AN-SAH were delineated to show that 2 patients (50%) had significant cardiac events (asystole/ STEMI) with associated tachyarrythmia noted in all 4 patients.

Survival (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate mortality risk factors.

The overall mortality rate in our cohort was 23% (20/87). The univariate examination of potential risk factors for mortality revealed that higher age (p=0.007), higher CKMB (p=0.029) and higher troponin (p=0.031) were all significantly associated with mortality. It also revealed that patients experiencing an MI during their episode had a 3.5 times greater risk of death (p=0.02; OR 3.46 CI: 1.18-10.12) compared to those without an MI. Lastly, results indicated that a WFNS of 4-5 posed a 12-fold increase in risk compared to those with a WFNS of 1-3 (p<0.001; OR 11.88 CI: 3.75- 37.68). Ejection fraction (EF) was excluded from statistical analysis since there were only 4 patients with EF <40.

The variables found to be significant on the univariate analysis were selected for the exploratory multivariable step-wise logistic regression analysis. The findings of this analysis suggested that WFNS [4, 5] and increased troponin levels were predictive of mortality in this sample. However, the traditionally used troponin cut-off (>0.3 mcg/L) was not found to be a significant predictor. The dataset was therefore divided into two groups around the median troponin, the lowest 50% and highest 50%, and the troponin level at that cut-point (1.0 mcg/L) was entered into the regression model to determine whether it more strongly predicted the mortality in this dataset. The final results indicated that patients with a WFNS of 4-5 had a nearly 33 times greater risk of death compared to those with WFNS of 1-3 (Exp(b) = 33.08; 95% CI: 5.85- 187.02) and that a troponin level >1.0 mcg/L resulted in roughly 10 times greater risk of death compared to those with a level <1.0 mcg/L (Exp(b)=9.70; 95% CI: 1.61-58.52). The overall mortality of our cohort was comparable to that of the national database inpatient sample (24.4% nationally vs 23% in this sample, p=0.436).

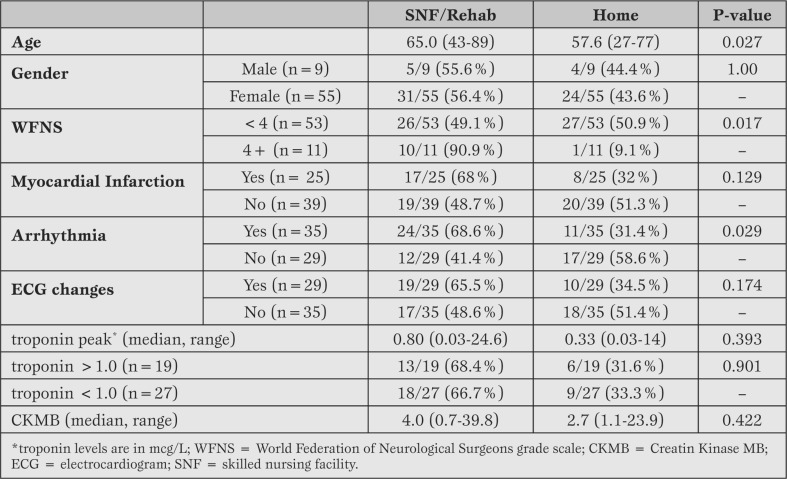

Discharge status (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate analysis of discharge status in 67 surviving patients.

As previously stated, 20/87 (23%) were in-hospital deaths. Thirty-six (41.4%) patients were discharged to SNF/Rehab and 28 (32.2%) were discharged to home. Three patients (3.4%) were discharged to hospice and were excluded from the remaining analysis due to the small sample size. The univariate examination of discharge status (SNF/Rehab vs home), suggested that older age (p=0.027), WFNS 4-5 (p=0.017) and development of an arrhythmia (p=0.029) were associated with an increased tendency toward discharge to SNF/Rehab compared to those discharged to home.

The variables found to be significant on the univariate analysis were selected for the exploratory multivariable step-wise logistic regression analysis. The findings of this analysis suggested that older age with an Exp(b) =1.06 (95% CI: 1.01-1.12), WFNS [4,5] with an Exp(b) =17.65 (95% CI: 1.77-176.3) and development of arrhythmias with an Exp(b) =3.60 (95% CI: 1.10-11.74) were all associated with an increased chance of being discharged to SNF/Rehab compared to discharge to home. Compared to the national discharge statistics, routine discharge home was similar (34.1% nationally vs 32.2% study sample, p=0.40). However, discharge to SNF/Rehab was significantly higher in our cohort (25.3% nationally vs 41.4% in study sample, p<0.001).

Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) was available for 52/87 (59.8%) of the study sample (Figure 1). Among those, 5/52(9.6%) were found to be GOS 3 (Severe Disability), 15/52 (28.8%) were GOS 4 (Moderate Disability) and 12/52 (23.1%) were GOS 5 (Good Recovery).

Figure 1.

Glascow Outcome Scale (GOS)

GOS1: Dead, GOS 2 Vegetative State, GOS 3 Severe Disability (able to follow commands/ unable to live independently), GOS 4 Moderate Disability (able to live independently; unable to return to work or school), GOS 5 Good Recovery (able to return to work or school).

DISCUSSION

Cardiac manifestations of intracranial non-traumatic SAH are an accepted phenomenon that affect in-patient outcomes and poses a challenge for neuro-intensivists. In our cohort, significant cardiac abnormalities were found in 14.1% of patients presenting with non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. The most frequent cardiac complication was arrhythmia, followed by myocardial infarction and new onset CHF. The location of the aneurysm did not influence the type of cardiac complication but the presence of intraventricular hemorrhage was significantly associated with ECG changes (p=0.037). The most common ECG finding consisted of T-wave inversion and ST depression suggesting subendocardial ischemia. However, having an ECG change did not correlate with having a MI or a poorer outcome. Among all of the cardiac complications, myocardial infarction and a troponin level greater than 1.0 mcg/L were associated with increased mortality and poorer outcomes.

Patients with diagnosed myocardial infarction had significant tendency for non-ST elevation infarctions. Tachyarrhythmias were significantly associated with NSTEMI. Incidence of bradyarrythmia, however, was comparable between the MI versus non-MI subgroups. Tachycardia increases the myocardial muscle oxygen demand therefore infarction associated with tachyarrythmias may suggest oxygen demand-flow mismatch. Coghlen et al. report increased mortality in association with relative tachycardia in patients with SAH [21].

In the present study we have determined the relative frequency of different cardiac manifestations in SAH and the influence of each abnormality to the overall outcome.

Cardiac outcomes. In patients with diagnosed MI (troponin >0.3 mcg/L) the inpatient mortality is 3.5 times more likely (OR 3.46, CI 1.18-10.12). Myocardial infarction was associated with a worsening of the outcome when considered in a univariate analysis, hence suggesting that MI is the most dangerous cardiac complication in patients with a SAH. Nevertheless, when entered in a multiple regression model, MI was not confirmed as an independent predictor of outcome. This was most likely explained by the interaction of age as a confounding variable and the lack of power of our study to accurately separate the two variables. For this reason, we were not able to firmly establish MI (traditional diagnosis with troponin >0.3 mcg/L) as an independent prognostic factor. Concomitantly, mortality was 5 times more likely in patients with troponin elevation greater than 1.0 mcg/L (OR 5.25, CI 1.51- 18.2). It must be stated that a “large” MI (i.e. troponin >1.0 mcg/L) reflects a larger quantity of necrotic myocardium and hence does serve as an independent predictor of overall outcome [22, 23].

Finally, when compared to the entire SAH patient population, the cohort with cardiac complications did not have a significant difference in outcome. Thereby suggesting that the neurological complications of SAH may outweigh the cardiac complications in regards to survivability.

Neurological outcome and discharge status. In our cohort, mortality in patients that present with WFNS grade >4 is almost 12 times more likely (OR 11.88, CI 3.75-37.58). The WFNS grade on admission is a well-established parameter to be significantly associated with outcome as well as the only independent predictor of survival, in neurosurgical literature. Multivariable subgroup analysis confirms the significance of the admission WNFS grade as a predictor of outcome in SAH patients even if they have associated cardiac complications.

Patient destination correlated with admission WFNS grade, older age and cardiac arrhythmias. Morbidity was determined with the Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) at 1 year follow-up. Of the 36 patients (41% of original cohort) followed, 75% (27 patients) were determined to have moderate disability or good recovery (GOS 4 or 5) at the time of discharge from the hospital. Approximately 25% of patients either succumbed to their injury or were sent to hospice care.

Angiographically negative SAH (perimesencephalic-SAH). As indicated above, not all of the patients with SAH and cardiac complications had an aneurysm as the cause. Four patients within the cohort were diagnosed with “angio-negative” SAH (AN-SAH), where a causative agent was not identified. Two complete cerebral angiograms where performed 10 days apart to confirm lack of vascular anomalies. AN-SAH is believed to be a benign entity with minimal neurological complications [24, 25], however systemic or cardiac manifestations have, in these patients, not been fully investigated. Though this subgroup is too small to be able to extrapolate outcome data, the cardiac complications were clinically significant. Two of the four patients succumbed to their cardiac complications secondary to asystole and STEMI, respectively. All four patients had tachyarrythmia associated ECG changes. AH-SAH though neurologically relatively benign can be associated with clinically significant systemic complications. Further investigation into the subgroup needs to be done in regards to systemic manifestations since they tend to usually present with a good WNFS score.

The descriptive statistical analysis presented in our study depicts the clinical evolution of cardiac manifestations in SAH as it relates to outcome, destination and morbidity. SAH is intrinsically associated with high morbidity and mortality. Concomitant cardiac complications have been linked to the severity of SAH and hence multiple mechanisms proposed. Some of these manifestations have been shown to be reversible [26, 27] and permanent; however their overall influence on outcome has been controversial [28, 29]. Coronary angiography, a gold standard for assessing coronary flow, may not be so helpful in this patient population [30, 31], though coronary vasospasm has been reported [32, 33]. The alternative theory of cardiac stunning secondary to catecholamine release is supported in literature [34,35,36,37].

In our cohort, we have established a variety of cardiac manifestations in SAH, suggesting that tachyarrhythmias are detrimental and long-term destination is primarily determined by the patient’s neurological status on admission and inpatient mortality of patients with cardiac abnormality is comparable to the national database.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations; first, selecting clinically evident cardiac manifestation overlooks the subgroup of patients with clinically silent troponin release, change in EF or even MI. Hence there is potential for under-estimation of the actual prevalence of cardiac abnormalities.

Second, female predominance in the analyzed cohort may affect cross gender extrapolation of short-term outcomes.

Third, the sample size is relatively limited in order to produce robust results when examining multiple factors. Finally, lack of adequate long-term cardiac follow up limits our understanding of outcomes in SAH survivors.

CONCLUSION

Clinically evident cardiac complications occurred in 14.1% of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Among this subset of patients, increased mortality was demonstrated in patients suffering from myocardial infarction and troponin levels greater than 1 mcg/L. The presence of intraventricular blood was associated with an increased frequency of arrhythmias. Overall, the WFNS score on admission remained the single most important predictor of mortality in SAH patients, even in the presence of cardiac complications.

Footnotes

Source of Support Nil.

Disclosures None declared.

Cite as: Ahmadian A, Mizzi A, Banasiak M, Downes K, Camporesi EM, Thompson Sullebarger J, Vasan R, Mangar D, van Loveren HR, Agazzi S. Cardiac manifestations of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Heart, Lung and Vessels. 2013; 5(3): 168-178.

References

- Di Pasquale G, Andreoli A, Lusa AM. et al. Cardiologic complications of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg Sci. 1998;42:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Azuma A, Sawada T. et al. Electrocardiographic score as a predictor of mortality after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Circ J. 2002;66:567–570. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer SA, LiMandri G, Sherman D. et al. Electrocardiographic markers of abnormal left ventricular wall motion in acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:889–896. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.5.0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JJ, Vanhecke TE, McCullough PA. Subarachnoid hemorrhage with neurocardiogenic stunning. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2010;11:254–263. doi: 10.3909/ricm0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers PJ, Wijdicks EF, Hasan D. et al. Serial electrocardiographic recording in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1989;20:1162–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.9.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvati M, Cosentino F, Artico M. et al. Electrocardiographic changes in subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to cerebral aneurysm. Report of 70 cases. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1992;13:409–413. doi: 10.1007/BF02312147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaroff JG, Rordorf GA, Newell JB. et al. Cardiac outcome in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage and electrocardiographic abnormalities. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:34–39. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199901000-00013. [discussion 39-40] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies KR, Gelb AW, Manninen PH. et al. Cardiac function in aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: a study of electrocardiographic and echocardiographic abnormalities. Br J Anaesth. 1991;67:58–63. doi: 10.1093/bja/67.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko GI, Dubowitz M, Senior R. Subarachnoid haemorrhage presenting as acute myocardial infarction with electromechanical dissociation arrest. Heart. 2001;86:340–340. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MB, Willet D, Keffer J. The use of cardiac troponin-I (cTnI) to determine the incidence of myocardial ischemia and injury in patients with aneurysmal and presumed aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998;140:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s007010050063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion DW, Segal R, Thompson ME. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and the heart. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:101–106. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198601000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi AR, Katayama M, Mills J. Cerebral hemorrhage: precipitating event for a tako-tsubo-like cardiomyopathy? Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:275–280. doi: 10.1002/clc.20165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H, Nishimura H, Imataka K. et al. Abnormal Q wave, ST-segment elevation, T-wave inversion, and widespread focal myocytolysis associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Jpn Circ J. 1996;60:254–257. doi: 10.1253/jcj.60.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster S. The electrocardiogram in subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br Heart J. 1960;22:316–320. doi: 10.1136/hrt.22.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Watanabe E, Yamada A. et al. Prognostic implications of left ventricular wall motion abnormalities associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Int Heart J. 2008;49:75–85. doi: 10.1536/ihj.49.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung P, Kopelnik A, Banki N. et al. Predictors of neurocardiogenic injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:548–551. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000114874.96688.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothavale A, Banki NM, Kopelnik A. et al. Predictors of left ventricular regional wall motion abnormalities after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2006;4:199–205. doi: 10.1385/NCC:4:3:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppadoro A, Citerio G. Subarachnoid hemorrhage: an update for the intensivist. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:74–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza O, Venditto A, Tufano R. Neurogenic pulmonary edema in subarachnoid hemorrage. Panminerva Med. 2011;53:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). [1988-2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp]

- Coghlan LA, Hindman BJ, Bayman EO. et al. Independent associations between electrocardiographic abnormalities and outcomes in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: findings from the intraoperative hypothermia aneurysm surgery trial. Stroke. 2009;40:412–418. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.528778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim LJ, Martinez EA, Faraday N. et al. Cardiac troponin I predicts short-term mortality in vascular surgery patients. Circulation. 2002;106:2366–2371. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000036016.52396.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta NJ, Khan IA, Gupta V. et al. Cardiac troponin I predicts myocardial dysfunction and adverse outcome in septic shock. Int J Cardiol. 2004;95:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong H, Melancon D, Tampieri D, Ethier R. The negative angiogram in subarachnoid haemorrhage. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:15–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00593209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanella M, Rainero I, Panciani PP. et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and negative angiography: clinical course and long-term follow-up. N Neurosurg Rev. 2001;34:477–484. doi: 10.1007/s10143-011-0323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulsara KR, McGirt MJ, Liao L. et al. Use of the peak troponin value to differentiate myocardial infarction from reversible neurogenic left ventricular dysfunction associated with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:524–528. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.3.0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deibert E, Barzilai B, Braverman AC. et al. Clinical significance of elevated troponin I levels in patients with nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:741–746. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.4.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuma W, Ito M, Kodama M. et al. Clinical and cardiac features of patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage presenting with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1294–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaroff JG, Leong J, Kim H. et al. Cardiovascular Predictors of Long-Term Outcomes After Non-Traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17:374–381. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9592-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PC, Lee SH, Hung HF. et al. Transient ST elevation and left ventricular asynergy associated with normal coronary artery and Tc-99m PYP Myocardial Infarct Scan in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Int J Cardiol. 1998;63:189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(97)00293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasu T, Owa M, Omura N. et al. Transient ST elevation and left ventricular asynergy associated with normal coronary artery in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Chest. 1993;103:1274–1275. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.4.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama Y, Tanaka H, Nuruki K, Shirao T. Prinzmetal's variant angina associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. Angiology. 1979;30:211–218. doi: 10.1177/000331977903000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuki K, Kodama Y, Onda J. et al. Coronary vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage as a cause of stunned myocardium. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:308–311. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.2.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachinski VC, Smith KE, Silver MD. et al. Acute myocardial and plasma catecholamine changes in experimental stroke. Stroke. 1986;17:387–390. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VH, Oh JK, Mulvagh SL, Wijdicks EF. Mechanisms in neurogenic stress cardiomyopathy after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2006;5:243–249. doi: 10.1385/NCC:5:3:243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naredi S, Lambert G, Eden E. et al. Increased sympathetic nervous activity in patients with nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2000;31:901–906. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf PD, Hamill RW, Lee LA. et al. The predictive value of catecholamines in assessing outcome in traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:875–882. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.6.0875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]