Abstract

Background

Treatment options for colorectal cancer (CRC) have improved substantially over the past 25 years. Measuring the impact of these improvements on survival outcomes is challenging, however, against the background of overall survival gains from advancements in the prevention, screening, and treatment of other conditions. Relative survival is a metric that accounts for these concurrent changes, allowing assessment of changes in CRC survival. We describe stage- and location-specific trends in relative survival after CRC diagnosis.

Methods

We analyzed survival outcomes for 233965 people in the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program who were diagnosed with CRC between January 1, 1975, and December 31, 2003. All models were adjusted for sex, race (black vs white), age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and diagnosis year. We estimated the proportional difference in survival for CRC patients compared with overall survival for age-, sex-, race-, and period-matched controls to account for concurrent changes in overall survival using two-sided Wald tests.

Results

We found statistically significant reductions in excess hazard of mortality from CRC in 2003 relative to 1975, with excess hazard ratios ranging from 0.75 (stage IV colon cancer; P < .001) to 0.32 (stage I rectal cancer; P < .001), indicating improvements in relative survival for all stages and cancer locations. These improvements occurred in earlier years for patients diagnosed with stage I cancers, with smaller but continuing improvements for later-stage cancers.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate a steady trend toward improved relative survival for CRC, indicating that treatment and surveillance improvements have had an impact at the population level.

Treatment options for colorectal cancer (CRC) have improved substantially over the past 25 years, especially for stage III and IV disease (1,2), with greater use of adjuvant therapy (3), multidrug regimens for metastatic disease (4,5), and targeted biologic agents (1,6,7). However, determining treatment impact on population-level survival is challenging because improvements in CRC treatment have occurred at the same time as advances in primary prevention, screening, and treatment strategies for a host of competing medical conditions.

Population scientists confront a choice when measuring the impact of interventions on survival after cancer diagnosis. Estimating cancer-specific survival focuses on deaths attributable to malignancy and requires accurate ascertainment of cause of death, which may be unreliably coded on death certificates (8). Relative survival focuses on the population burden of deaths from a particular cancer by comparing survival among cancer patients with survival in an otherwise similar population not known to have cancer (9–11). Relative survival is an especially useful tool for identifying the extent to which advances in cancer therapeutics have an impact at the population level because this approach places changes in survival after diagnosis in the context of population-level changes in survival.

In this article, we describe trends in relative survival after CRC diagnosis. Using nearly 30 years of population-based tumor registry data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (12) allowed us to estimate relative survival after CRC diagnosis by stage and tumor site in the colon or rectum (13).

Methods

Study Population

We analyzed data from the SEER Program for people diagnosed with CRC between January 1, 1975, and December 31, 2003, with follow-up through December 31, 2010 (12). We excluded people diagnosed in 2004 and later because in 2004 the SEER Program shifted to a collaborative staging approach that created a discontinuity in stage definitions with less than 6 years of follow-up after this change (14). We analyzed data from nine SEER registries that began collecting data in 1975 or earlier: Atlanta (metropolitan), Connecticut, Detroit (metropolitan), Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, San Francisco–Oakland, Seattle (Puget Sound), and Utah. We restricted analyses to people identified as black or white race, excluding people of other and unknown races, because our analyses required reliable estimates of population-level expected survival; these estimates are available for blacks and whites but not other racial groups. We did not exclude people identified as having Hispanic ethnicity. We excluded patients with unstaged disease. This study was approved by the Group Health Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was not required from patients.

Outcome Measure

We evaluated the time from CRC diagnosis to death from any cause. Our analyses focused on relative survival: the ratio of survival of persons diagnosed with CRC compared with survival of persons without CRC.

Survival of persons without CRC (ie, expected survival) is influenced by age, race, sex, and time period. Expected survival in persons not diagnosed with CRC was obtained from survival in the general US population, available in SEER*Stat from the National Center for Health Statistics (15). SEER*Stat uses these survival data to generate yearly expected survival by constructing a cohort of individuals who were not diagnosed with CRC who match the CRC-diagnosed cohort on race, sex, and birth date. There has been considerable debate about how expected survival should be calculated (16,17). Our analyses reconstructed the non-CRC cohort when a case subject was excluded from the observed survival risk set (ie, after CRC death or loss to follow-up) to maintain matching of the two cohorts for race, sex, and age distributions.

Disease Location

Colon cancers included cancers in the sigmoid colon, descending colon, splenic flexure, transverse colon, hepatic flexure, ascending colon, and cecum, and cancers in the large intestine, not otherwise specified. Rectal cancers included cancers in the rectum and rectosigmoid junction. Although patients with rectosigmoid cancer represent a mix of patients with true colon cancer (above the peritoneal reflection) and patients with true rectal cancer (below the peritoneal reflection), this distinction is not reliably recorded in SEER data.

Stage at Diagnosis

Staging was based on the fifth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system (13). AJCC staging was not recorded by SEER registrars before 1988, so we constructed AJCC staging based on the tumor (T) and nodal (N) component measures of TNM staging (18). The categories we used to define stage at diagnosis were consistent with those in the sixth edition of AJCC staging (19).

Statistical Analysis

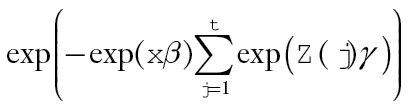

We estimated relative survival by comparing observed survival after diagnosis with CRC to expected survival based on age, sex, and race. We used an additive hazard model (10,11) with an exponential form for excess hazard (10) so that the overall hazard is given by

|

(1) |

where λ*(x,t) is the expected hazard in the absence of CRC diagnosis and exp[xβ+α(t)γ] is the excess hazard due to diagnosis with CRC. Both the expected and excess hazards vary by age, sex, and race; x are fixed covariables, such as age at diagnosis and sex, and  are time-varying covariables, such as time since diagnosis. The expected hazard λ*(x,t) may depend on a subset of the covariables included in the relative survival model. We applied this model to SEER data using annual intervals (11). Covariable information is updated with each new interval, so that

are time-varying covariables, such as time since diagnosis. The expected hazard λ*(x,t) may depend on a subset of the covariables included in the relative survival model. We applied this model to SEER data using annual intervals (11). Covariable information is updated with each new interval, so that  is the value of the covariable at the end of the t-th interval and is fixed throughout the interval. Under this model, excess hazard is proportional across covariable groups, and the survival of individuals diagnosed with CRC is proportional to survival of individuals in the general population. Models were restricted so that survival in patients diagnosed with CRC could not exceed survival in the general population.

is the value of the covariable at the end of the t-th interval and is fixed throughout the interval. Under this model, excess hazard is proportional across covariable groups, and the survival of individuals diagnosed with CRC is proportional to survival of individuals in the general population. Models were restricted so that survival in patients diagnosed with CRC could not exceed survival in the general population.

We used a generalized linear model with a binomial error structure to describe the number of deaths among individuals diagnosed with CRC relative to the number of expected deaths in each 1-year follow-up interval, with a complementary log–log link function (10).

We estimated separate models for eight stage and location groups, separating colon and rectal cancers each into stage I, II, III, and IV disease. All models included sex, race (black vs white), age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and diagnosis year. Age in years at diagnosis was coded as a categorical variable, consistent with SEER reporting, as 20 to 49 years, 50 to 59 years, 60 to 69 years, 70 to 79 years, and 80 years and older. Diagnosis year was coded as an integer and was assigned the value at the beginning of the 1-year period. We included diagnosis year in models as a continuous variable that was a piecewise linear function of year, allowing changes in slope at 1980, 1990, and 2000. For stage I colon and rectal cancers, we did not allow a change in slope in 2000 because models with this change overfit the data.

Years since diagnosis, noted by t, was a time-varying covariable updated in 1-year increments at the end of the yearly interval, so that in the year of diagnosis t = 1, the next year t = 2, and so on up to t = 25. We included year since diagnosis in survival models as a continuous variable that was a piecewise linear function of year. We allowed changes in slope at 2, 3, 5, 10, and 15 years after diagnosis to allow rapid change in excess hazards in the first few years after a CRC diagnosis followed by continuing but more gradual change.

We included interactions between age at diagnosis and years since diagnosis for some stage–location groups to allow changes in excess hazard after diagnosis to vary across age groups (10). We examined deviance statistics and residuals to assess the goodness of fit of survival models but relied primarily on residuals in this large sample.

Estimated Covariable Effects.

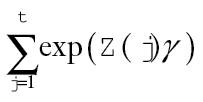

Excess hazard ratios were estimate by evaluating exp[xβ+α(t)γ]. Cumulative excess hazard to time t was estimated by  where

where . Relative survival to time t was estimated by

. Relative survival to time t was estimated by with point-wise 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on a parametric bootstrap (20). For fixed (time-invariant) covariables, the excess hazard ratio is equal to the cumulative excess hazard ratio, so that exp(β) estimates the excess hazard ratio for x = 1 vs x = 0 and estimates the log-difference in the cumulative relative survival ratio. Similarly, for a time-varying covariable, the excess hazard ratio is based on exp(α(t)γ). Statistical tests were based on two-sided Wald tests of H0:β = 0 (or H0:α(t)γ=0). Cumulative excess hazard ratios and cumulative relative survival are functions of

with point-wise 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on a parametric bootstrap (20). For fixed (time-invariant) covariables, the excess hazard ratio is equal to the cumulative excess hazard ratio, so that exp(β) estimates the excess hazard ratio for x = 1 vs x = 0 and estimates the log-difference in the cumulative relative survival ratio. Similarly, for a time-varying covariable, the excess hazard ratio is based on exp(α(t)γ). Statistical tests were based on two-sided Wald tests of H0:β = 0 (or H0:α(t)γ=0). Cumulative excess hazard ratios and cumulative relative survival are functions of  and take into account changes in excess hazard over time.

and take into account changes in excess hazard over time.

All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The sample included data from 233965 people diagnosed with CRC (Table 1). A small but noteworthy fraction of patients (7.1%) were diagnosed before their 50th birthday. Approximately 58% of patients were diagnosed between the ages of 60 and 79 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of people diagnosed with incident antemortem colorectal cancer reported to the SEER registry, 1975–2003

| Characteristic | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | |

| No. | 29 825 | 17 206 | 58 575 | 16 538 | 43 857 | 16 759 | 38 647 | 12 558 |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 20–49 | 5.3% | 7.7% | 5.5% | 6.9% | 7.8% | 10.3% | 7.8% | 9.5% |

| 50–59 | 13.7% | 17.8% | 11.1% | 16.7% | 14.2% | 19.8% | 14.7% | 17.3% |

| 60–69 | 27.6% | 30.1% | 23.7% | 29.1% | 25.7% | 30.2% | 26.4% | 29.0% |

| 70–79 | 33.4% | 29.9% | 33.5% | 30.4% | 30.9% | 27.0% | 30.2% | 27.9% |

| ≥80+ | 19.9% | 14.5% | 26.2% | 16.9% | 21.3% | 12.7% | 20.9% | 16.2% |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | 8.4% | 5.2% | 7.9% | 6.1% | 9.3% | 6.8% | 11.6% | 8.7% |

| White | 91.6% | 94.8% | 92.1% | 93.9% | 90.7% | 93.2% | 88.4% | 91.3% |

| Year of diagnosis* | ||||||||

| 1975–1979 | 11.8% | 17.2% | 15.8% | 18.1% | 14.0% | 15.2% | 18.1% | 19.3% |

| 1980–1986 | 22.0% | 25.5% | 25.9% | 27.0% | 24.6% | 25.4% | 26.2% | 26.0% |

| 1987–1993 | 25.0% | 22.4% | 25.1% | 23.9% | 24.4% | 24.3% | 23.9% | 23.3% |

| 1994–1999 | 22.4% | 19.7% | 20.3% | 18.9% | 21.8% | 20.6% | 19.2% | 19.0% |

| 2000–2003 | 18.7% | 15.1% | 12.9% | 12.1% | 15.1% | 14.5% | 12.5% | 12.3% |

* The 2000 to 2003 and 1975 to 1979 time periods span fewer years than the other 6-year periods and therefore have fewer cases for each stage-location group.

Table 2 shows excess hazard ratios for death after CRC diagnosis for fixed covariables based on separate stage and cancer location models. Women had lower excess mortality than men for stage I rectal cancer, stage II colon and rectal cancers, and stage III rectal cancer. We found no sex differences in excess mortality for the other stage-location combinations. Blacks had statistically significantly greater excess mortality than whites for all stage and location groups; relative differences were largest for stage I cancers and decreased with increasing stage. We found statistically significant reductions in excess mortality for more recently diagnosed cancers for all stage and location groups. The excess hazard of mortality from CRC was statistically significantly reduced from 2003 relative to 1975, with excess hazard ratios ranging from 0.75 (stage IV colon cancer; P < .001) to 0.32 (stage I rectal cancer; P < .001), indicating improvements in relative survival for all stages and cancer locations. These improvements occurred in earlier years for patients diagnosed with stage I cancers, with smaller but continuing improvements for later-stage cancers. For example, there were relatively large reductions in excess mortality for stage I colon and rectal cancer from 1980 to 1990. The greatest overall reductions in excess hazard occurred for early-stage cancers and stage III rectal cancer.

Table 2.

Excess hazard ratios for death among patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer by tumor location and stage, with P values based on two-sided Wald tests in parentheses*

| Characteristic | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | |

| Female, relative to male | 1.00 (.95) | 0.71 (<.001) | 0.87 (<.001) | 0.94 (.01) | 0.98 (.14) | 0.9 (<.001) | 1.00 (.94) |

0.99 (.71) |

| Black, relative to white | 1.73 (<.001) | 1.88 (<.001) | 1.51 (<.001) | 1.38 (<.001) | 1.13 (<.001) | 1.27 (<.001) | 1.08 (<.001) | 1.25 (<.001) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||

| 2003, relative to 2000 | 1.00 (.82) | 0.97 (.21) | 0.87 (.03) | 0.85 (.08) | 0.94 (.15) | 0.83 (.008) | 0.89 (<.001) | 0.92 (.13) |

| 2003, relative to 1990 | 0.98 (.82) | 0.89 (.21) | 0.75 (<.001) | 0.69 (<.001) | 0.81 (<.001) | 0.61 (<.001) | 0.83 (<.001) | 0.8 (<.001) |

| 2003, relative to 1980 | 0.55 (<.001) | 0.42 (<.001) | 0.61 (<.001) | 0.58 (<.001) | 0.65 (<.001) | 0.44 (<.001) | 0.77 (<.001) | 0.68 (<.001) |

| 2003, relative to 1975 | 0.47 (<.001) | 0.32 (<.001) | 0.52 (<.001) | 0.51 (<.001) | 0.59 (<.001) | 0.43 (<.001) | 0.75 (<.001) | 0.69 (<.001) |

* Estimates are based on models that adjust for sex, race, age, year of diagnosis, and time since diagnosis.

Table 3 shows excess hazard ratios as a function of age at diagnosis with CRC at 1, 5, and 10 years after diagnosis, compared with patients diagnosed between the ages of 60 and 69 years. Diagnosis at younger ages was generally associated with lower excess hazards than diagnosis at older ages. Age effects did not vary with time since diagnosis for stage I colon cancer. For most other stage and location groups, the effect of age at diagnosis diminished with increasing time since diagnosis, although patients with stage I rectal cancer diagnosed before age 60 years had greater excess hazards 10 years after diagnosis than patients diagnosed between 60 and 69 years. Diagnosis at older ages was generally associated with greater excess hazard, although patients diagnosed at older age with stages II, III, and IV colon cancer had lower excess hazard 5 years after diagnosis, relative to patients diagnosed between 60 and 69 years.

Table 3.

Stage-specific excess hazard ratios for death as a function of age, by time elapsed since diagnosis, with P values based on two-sided Wald tests in parentheses*

| Age group | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon† | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | |

| One-year excess hazard ratio | ||||||||

| Age, y20–4950–5960–6970–79≥80 | ||||||||

| 0.46 (<.001) | 0.23 (.002) | 0.51 (<.001) | 0.44 (<.001) | 0.810.001 | 0.89 (.28) | 0.81 (<.001) | 0.78 (<.001) | |

| 0.78 (.001) | 0.54 (.005) | 0.71 (<.001) | 0.65 (.001) | 0.82<0.001 | 0.73 (<.001) | 0.88 (<.001) | 0.83 (<.001) | |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 1.50 (<.001) | 2.6 (<.001) | 2.02 (<.001) | 1.75 (<.001) | 1.7<0.001 | 1.66 (<.001) | 1.28 (<.001) | 1.29 (<.001) | |

| 1.40 (<.001) | 4.38 (<.001) | 2.24 (<.001) | 2.39 (<.001) | 2.06<0.001 | 2.25 (<.001) | 1.58 (<.001) | 1.66 (<.001) | |

| Five-year excess hazard ratio | ||||||||

| Age, y20–4950–5960–6970–79≥80 | ||||||||

| 0.46 (<.001) | 0.90 (.53) | 0.73 (.001) | 0.99 (.95) | 0.96 (.61) | 0.97 (.75) | 0.71 (.003) | 0.95 (.76) | |

| 0.78 (.001) | 0.78 (.04) | 0.87 (.04) | 1 (.98) | 1.02 (.72) | 1.16 (.04) | 0.90 (.27) | 1.03 (.85) | |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 1.50 (<.001) | 0.93 (.44) | 0.59 (<.001) | 1.03 (.74) | 0.77 (<.001) | 0.99 (.84) | 0.75 (.001) | 0.80 (.11) | |

| 1.40 (<.001) | 1.56 (<.001) | 0.65 (<.001) | 1.40 (<.001) | 0.93 (.17) | 1.34 (<.001) | 0.93 (.43) | 1.03 (.83) | |

| Ten-year excess hazard ratio | ||||||||

| Age, y20–4950–5960–6970–79≥80 | ||||||||

| 0.46 (<.001) | 1.56 (.04) | 1.12 (.43) | 0.62 (.02) | 0.95 (.75) | 0.85 (.29) | 1.12 (.69) | 2.33 (.02) | |

| 0.78 (.001) | 2.24 (<.001) | 0.90 (.37) | 1.02 (.88) | 1.15 (.21) | 0.68 (.003) | 1.18 (.53) | 1.03 (.94) | |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 1.50 (<.001) | 3.33 (<.001) | 1.34 (<.001) | 1.01 (.93) | 0.91 (.35) | 0.87 (.27) | 0.60 (.04) | 2.14 (.02) | |

| 1.4 (<.001) | 5.61 (<.001) | 1.49 (<.001) | 1.38 (.007) | 1.1 (.33) | 1.18 (.21) | 0.74 (.24) | 2.75 (.002) | |

* Estimates are based on separate models for each stage and location group that adjusted for sex, race, age, year of diagnosis, and time since diagnosis. P values are associated with tests for differences in excess hazard, compared with 60- to 69-year-olds, within stage and location groups.

† One-, five-, and ten-year excess hazard ratio estimates are identical because the model does not include an interaction between age at diagnosis and time since diagnosis

Table 4 shows cumulative relative survival by stage and location for white men (the reference group) diagnosed in 1990. There were modest steady decreases in cumulative relative survival after diagnosis with stage I colon cancer. In contrast, cumulative relative survival for stage IV colon and rectal cancers decreased rapidly in the 5 years after diagnosis. Patterns of cumulative relative survival across stage and location groups varied between these two extremes. With the exception of stage IV disease, patients diagnosed with rectal cancer had poorer cumulative relative survival than those diagnosed with same-stage colon cancer. With few exceptions, patients diagnosed at younger ages had better cumulative relative survival than patients diagnosed at older ages.

Table 4.

Cumulative relative survival for white men diagnosed with colon or rectal cancer in 1990 as a function of time elapsed since diagnosis, by age at diagnosis and stage and location of cancer, with 95% confidence intervals based on a parametric bootstrap (20) shown in parentheses

| Time | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | Colon | Rectum | |

| Diagnosed at age 20–49 years | ||||||||

| Years since diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.99 (0.99 to 0.99) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.98) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | 0.91 (0.90 to 0.92) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.94) | 0.48 (0.46 to 0.50) | 0.56 (0.52 to 0.59) |

| 5 | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.96) | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.87) | 0.77 (0.74 to 0.80) | 0.61 (0.58 to 0.63) | 0.56 (0.53 to 0.60) | 0.09 (0.08 to 0.10) | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.11) |

| 10 | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98) | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.92) | 0.80 (0.78 to 0.81) | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.71) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.56) | 0.45 (0.41 to 0.49) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.06) |

| 25 | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.97) | 0.86 (0.83 to 0.89) | 0.72 (0.69 to 0.74) | 0.62 (0.58 to 0.66) | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.52) | 0.40 (0.36 to 0.44) | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.07) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.05) |

| Diagnosed at age 50–59 years | ||||||||

| Years since diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.97) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98) | 0.91 (0.90 to 0.92) | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.95) | 0.45 (0.43 to 0.47) | 0.54 (0.51 to 0.57) |

| 5 | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.98) | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.95) | 0.83 (0.81 to 0.84) | 0.77 (0.74 to 0.79) | 0.59 (0.57 to 0.61) | 0.55 (0.52 to 0.58) | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.08) | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.09) |

| 10 | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.96) | 0.89 (0.87 to 0.91) | 0.77 (0.75 to 0.79) | 0.65 (0.62 to 0.68) | 0.52 (0.50 to 0.54) | 0.44 (0.41 to 0.47) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.06) |

| 25 | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.95) | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87) | 0.71 (0.69 to 0.73) | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.57) | 0.50 (0.48 to 0.52) | 0.40 (0.37 to 0.43) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.04) | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.05) |

| Diagnosed at age 60–69 years | ||||||||

| Years since diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.98 (0.98 to 0.98) | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.96) | 0.95 (0.95 to 0.96) | 0.89 (0.89 to 0.90) | 0.92 (0.91 to 0.93) | 0.40 (0.39 to 0.42) | 0.47 (0.45 to 0.50) |

| 5 | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.97) | 0.93 (0.92 to 0.94) | 0.82 (0.81 to 0.83) | 0.73 (0.71 to 0.75) | 0.58 (0.57 to 0.60) | 0.52 (0.50 to 0.54) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) |

| 10 | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.95) | 0.89 (0.88 to 0.90) | 0.75 (0.74 to 0.77) | 0.62 (0.59 to 0.64) | 0.51 (0.50 to 0.53) | 0.41 (0.38 to 0.43) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) |

| 25 | 0.92 (0.91 to 0.93) | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.88) | 0.66 (0.64 to 0.68) | 0.46 (0.43 to 0.50) | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.51) | 0.36 (0.33 to 0.38) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03) |

| Diagnosed at age 70–79 years | ||||||||

| Years since diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.98) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.97) | 0.92 (0.91 to 0.92) | 0.92 (0.91 to 0.93) | 0.83 (0.82 to 0.84) | 0.87 (0.86 to 0.88) | 0.31 (0.30 to 0.33) | 0.38 (0.35 to 0.41) |

| 5 | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.96) | 0.90 (0.89 to 0.92) | 0.82 (0.81 to 0.83) | 0.70 (0.68 to 0.73) | 0.55 (0.53 to 0.57) | 0.49 (0.46 to 0.52) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) |

| 10 | 0.91 (0.90 to 0.92) | 0.84 (0.82 to 0.86) | 0.76 (0.74 to 0.77) | 0.60 (0.56 to 0.63) | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.52) | 0.39 (0.36 to 0.42) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.05) |

| 25 | 0.88 (0.87 to 0.90) | 0.64 (0.57 to 0.70) | 0.59 (0.56 to 0.62) | 0.36 (0.29 to 0.41) | 0.39 (0.35 to 0.42) | 0.24 (0.19 to 0.28) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.02) |

| Diagnosed at age ≥80 years | ||||||||

| Years since diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.98) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.96) | 0.91 (0.90 to 0.92) | 0.89 (0.88 to 0.90) | 0.79 (0.78 to 0.81) | 0.83 (0.81 to 0.84) | 0.24 (0.22 to 0.25) | 0.29 (0.26 to 0.32) |

| 5 | 0.95 (0.95 to 0.96) | 0.84 (0.82 to 0.87) | 0.80 (0.79 to 0.81) | 0.62 (0.58 to 0.65) | 0.49 (0.46 to 0.51) | 0.38 (0.34 to 0.41) | 0.03 (0.03 to 0.04) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) |

| 10 | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.93) | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.78) | 0.74 (0.72 to 0.75) | 0.49 (0.45 to 0.53) | 0.43 (0.40 to 0.45) | 0.28 (0.24 to 0.31) | 0.02 (0.02 to 0.03) | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.02) |

| 25 | 0.89 (0.87 to 0.91) | 0.48 (0.38 to 0.56) | 0.56 (0.53 to 0.59) | 0.24 (0.18 to 0.30) | 0.32 (0.28 to 0.35) | 0.14 (0.10 to 0.18) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.01) |

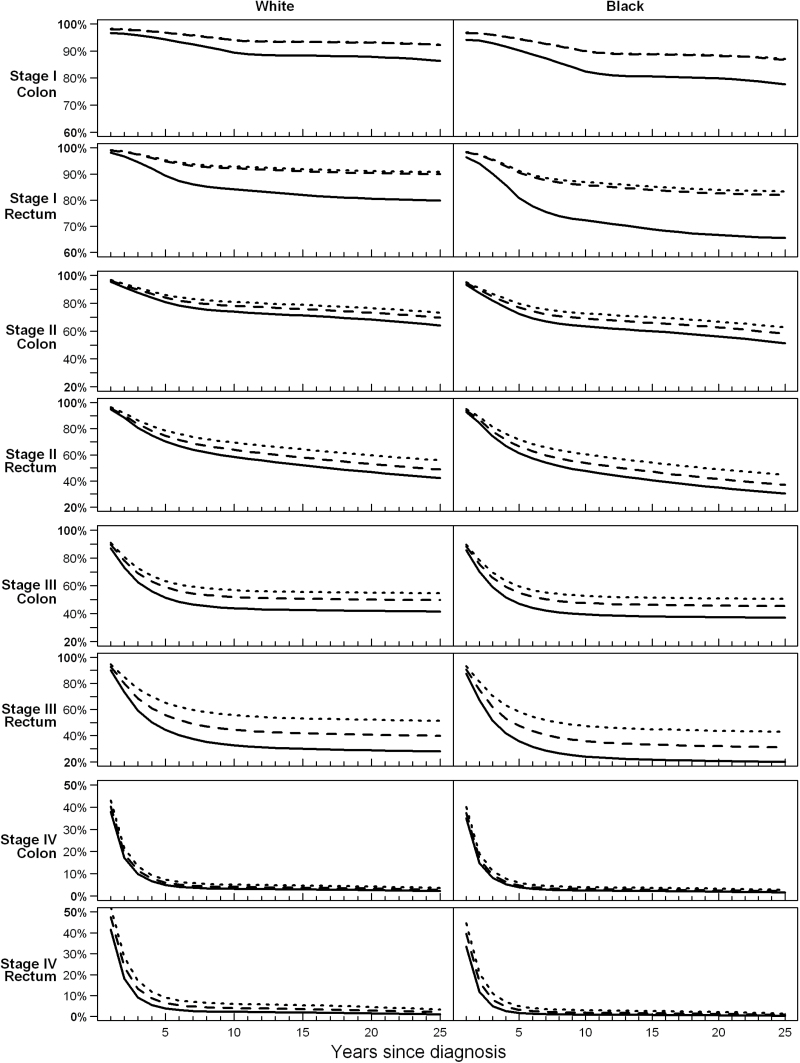

Figure 1 provides descriptive results and shows cumulative relative survival estimates among women diagnosed with CRC between the ages of 60 and 69 years during calendar years 1980, 1990, and 2000 to demonstrate improvements in survival over time for all stage and location groups. The scale of vertical axes varies across cancer stages to better demonstrate changes over time. Improvements in survival occurred earlier for women diagnosed with stage I cancers, with clear improvements in survival after diagnosis with stage I rectal or colon cancer between 1980 and 1990. Consistent with results in Table 2, there were smaller but continuing improvements for stage II and III CRC survival. Relatively large improvements were seen for stage III rectal cancer. Although it is difficult to see in the figure, there were also improvements in survival for stage IV CRC (as shown in Table 2).

Figure 1.

Cumulative relative survival among women aged 60 to 69 years diagnosed with colorectal cancer in 1980 (solid lines), 1990 (dashed lines) and 2000 (dotted lines), based on models that adjust for sex, race, age, year of diagnosis, and time since diagnosis.

Discussion

Our analyses clearly demonstrate reductions in the population-level impact of CRC on survival since 1975. Our findings of lower excess hazard in women than in men and higher excess hazard in blacks than in whites are consistent with published CRC-specific survival estimates (21–23). Similarly, our findings that excess hazard declined over time for stage I CRC, with smaller improvements for later-stage CRC, are consistent with published findings of improvements in stage-specific CRC survival (23). By distinguishing between colon and rectal cancers, we demonstrated poorer survival outcomes for patients diagnosed with rectal cancer vs those diagnosed with colon cancer but also found clear survival gains for patients diagnosed with stage III rectal cancer that would have been obscured in combined analyses.

A drawback of examining CRC-specific survival is that it is not clear whether secular trends are a consequence of better cancer treatment or of better overall health status and medical care. By examining relative survival, our analyses provide evidence that treatment advances have contributed to this favorable trend. In the 1970s there was only one efficacious drug, 5-fluorouracil, for treatment of advanced CRC. There are now multiple efficacious chemotherapy drugs for CRC, including irinotecan (introduced in 1996) (4), oxaliplatin (introduced in 2002) (5), and the biologic agents bevacizumab and cetuximab (both introduced in 2004) (1,6,7). The trends we identify suggest that treatment benefits demonstrated in clinical trials have translated to lower CRC case fatality.

Analysis of secular trends in relative CRC survival requires consistent cancer staging, but SEER stage coding changed over our study period. Constructing AJCC stage for patients diagnosed with colon cancer was relatively straightforward because more than 95% of individuals with stage I to III colon cancer undergo cancer-directed surgery, resulting in cancer site–specific surgery and staging codes. However, changes in neoadjuvant treatment of rectal cancer make accurate staging of rectal cancer difficult (24). Increasingly, patients diagnosed with rectal and rectosigmoid cancer are treated with preoperative chemotherapy and radiation, so the recorded pathological stage does not necessarily correspond to disease severity at diagnosis. This is a limitation of the SEER data that we acknowledge but cannot entirely circumvent.

Similarly, within-stage migration could have contributed to improvements in relative survival. For example, if stage III colon cancers diagnosed after 2000 were a bit less advanced than those identified in 1985, we might identify declining case fatality absent improvements in treatment. One possible mechanism for within-stage shifts is an increase in the number of lymph nodes retrieved at surgery (25), although two recent studies found no evidence that the number of lymph nodes retrieved is associated with lymph node positivity rates (25,26). It is possible that within-stage migration had some effect on our findings, but it is implausible as the major source of the trends we observe.

We limited our analyses to patients diagnosed through 2003 because of changes in staging and availability of follow-up after the most recent modification to SEER staging in 2004. Therefore we cannot draw conclusions about survival changes in more recent years.

When estimating relative survival models, we implicitly assumed that patients diagnosed with CRC had the same risk of non-CRC death as age-, race-, and sex-matched individuals from the general population. Risk factors for CRC include obesity (27), diabetes (28), and smoking (29), with estimated relative risks of CRC as high as 1.3 for patients with diabetes. These factors are also associated with an increased risk of non-CRC death, potentially resulting in overestimation of expected survival in the general population and underestimation of relative survival, although simulation studies suggest relatively small bias given the degree of association between risk factors and CRC (30). Our focus on differences in relative survival over time and across patient groups also reduces the potential for bias.

Diffusion of CRC screening may have driven some of the observed changes in survival, biasing toward better estimated survival because of length and lead-time bias (31). Length bias occurs when screening identifies more indolent disease with better natural history than clinically detected disease, regardless of treatment. Lead-time bias occurs when survival appears to be longer because screening shifts diagnosis to an earlier point but does not change the age at death. Uptake of CRC screening increased during the study period. Medicare began universal coverage of CRC screening in 1988, with colonoscopy included as a covered screening modality in 2001 (32). However, the extent of screening uptake is unclear because studies usually describe CRC testing, which combines asymptomatic screening and diagnostic assessments. The prevalence of lifetime CRC testing increased from less than 30% in 1987 to approximately 45% at the end of our study period in 2003 (33). In 2000, about 38% of adult Americans aged 50 to 75 were up-to-date for CRC screening based on prior tests (34).

Randomized trials (35–38) and observational studies (39,40) show that screening with fecal occult blood tests results in earlier stage at detection; flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy likely have similar effects. Because of this, we expected screening diffusion to have the largest effect on stage I CRC. Interestingly, the largest improvements in survival from stage I CRC occurred in the 1980s, when screening was first diffusing through the US population and screening rates were relatively low (33). Differential screening uptake might also underlie some age, sex, and racial differences in stage-specific CRC survival (41,42).

Further research is needed to disentangle the relative impact of screening and treatment on improvements in stage-specific CRC survival. Such research has been stymied by the inability to distinguish screening from diagnostic colonoscopy in administrative datasets. An alternative approach is to use simulation models to distinguish between the competing effects of changes in risk factors, screening, and treatment on cancer survival (43,44), but these models require assumptions about patterns of screening diffusion.

Regardless of the contributions of screening and treatment, our results demonstrate steady overall improvements in survival for all CRC stages that were detectable even against the background of improved overall survival.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award No. U01CA52959.

Supplementary Material

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1. de Gramont A, Chibaudel B, Larsen AK, Tournigand C, Andre T, Gercor French Oncology Research Group. The evolution of adjuvant therapy in the treatment of early-stage colon cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10(4):218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Graham JS, Cassidy J. Adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12(1):99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adjuvant Therapy for Patients with Colon and Rectum Cancer. NIH Consensus Development Conference Statement, April 16–18, 1990. http://consensus.nih.gov/1990/1990adjuvanttherapycolonrectalcancer079html.htm Accessed September 27, 2013. [PubMed]

- 4. Saltz LB, Cox JV, Blanke C, et al. Irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. Irinotecan Study Group. N Engl J Med. 28 2000;343(13):905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of fluorouracil plus leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin combinations in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chu E. An update on the current and emerging targeted agents in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2012;11(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lucas AS, O’Neil BH, Goldberg RM. A decade of advances in cytotoxic chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10(4):238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yin D, Morris CR, Bates JH, German RR. Effect of misclassified underlying cause of death on survival estimates of colon and rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(14):1130–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perme MP, Stare J, Esteve J. On estimation in relative survival. Biometrics. 2012;68(1):113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Hills M, Hakulinen T. Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med. 2004;23(1):51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hakulinen T, Tenkanen L. Regression analysis of relative survival rates. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat. 1987;36(3):309–317. [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Incidence—Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Registries Research Data. http://seer.cancer.gov/data/seerstat/nov2011/ Accessed September 27, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleming I, Cooper Jay S., Henson E, et al. , eds. American Joint Committee on Cancer Cancer Staging Manual. 5th ed Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson C, ed. SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Cancer Institute. SEER*Stat Software. http://www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/ Accessed August 20, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hakulinen T. On long-term relative survival rates. J Chronic Dis. 1977;30(7):431–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hakulinen T. Cancer survival corrected for heterogeneity in patient withdrawal. Biometrics. 1982;38(4):933–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schrag D. AJCC Staging: Staging Colon Cancer Patients Using the TNM System From 1975 to the Present. http://www.mskcc.org/mskcc/html/84761.cfm Accessed February 6, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Comparison Guide: Cancer Staging Manual. http://www.cancerstaging.org/products/ajccguide.pdf Accessed August 20, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Efron B. The Jackknife, the Boostrap and other Resampling Plans. Philadelphia, PA: Siam Publications; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cook MB, McGlynn KA, Devesa SS, Freedman ND, Anderson WF. Sex disparities in cancer mortality and survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1629–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yothers G, Sargent DJ, Wolmark N, et al. Outcomes among black patients with stage II and III colon cancer receiving chemotherapy: an analysis of ACCENT adjuvant trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(20):1498–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Robbins AS, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer mortality rates from 1985 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(4):401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Minsky BD. Progress in the treatment of locally advanced clinically resectable rectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10(4):227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parsons HM, Tuttle TM, Kuntz KM, Begun JW, McGovern PM, Virnig BA. Association between lymph node evaluation for colon cancer and node positivity over the past 20 years. JAMA. 2011;306(10):1089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Porter GA, Urquhart R, Bu J, Johnson P, Rayson D, Grunfeld E. Improving nodal harvest in colorectal cancer: so what? Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(4):1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371(9612):569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(22):1679–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(23):2765–2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sarfati D, Blakely T, Pearce N. Measuring cancer survival in populations: relative survival vs cancer-specific survival. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):598–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Croswell JM, Ransohoff DF, Kramer BS. Principles of cancer screening: lessons from history and study design issues. Semin Oncol. 2010;37(3):202–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Freeman JL, Klabunde CN, Schussler N, Warren JL, Virnig BA, Cooper GS. Measuring breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screening with medicare claims data. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Richardson IC, Rim SH, Plescia M. Vital Signs: Colorectal cancer screening among adults aged 50–75 years—United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(26):808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1467–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Towler B, Irwig L, Glasziou P, Kewenter J, Weller D, Silagy C. A systematic review of the effects of screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, hemoccult. BMJ. 1998;317 (7158):559–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1472–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(5):434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Courtney E, Chong D, Tighe R, Easterbrook J, Stebbings W, Hernon J. Screen-detected colorectal cancers show improved cancer-specific survival when compared with cancers diagnosed via the 2-week suspected colorectal cancer referral guidelines. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(2):177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gill MD, Bramble MG, Rees CJ, Lee TJ, Bradburn DM, Mills SJ. Comparison of screen-detected and interval colorectal cancers in the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(3):417–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Reed G, Field TS, Fletcher RH. Socioeconomic and racial patterns of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees in 2000 to 2005. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(8):2170–2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Klabunde CN, Cronin KA, Breen N, Waldron WR, Ambs AH, Nadel MR. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(8):1611–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1784–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2009;116(3):544–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.