Abstract

A series of 5′-nor carbocyclic “reverse” flexible nucleosides or “fleximers” have been designed wherein the nucleobase scaffold resembles a “split” purine as well as a substituted pyrimidine. This modification was employed to explore recognition by both purine and pyrimidine metabolizing enzymes. The synthesis of the carbocyclic fleximers and the results of their preliminary biological screening are described herein.

Introduction

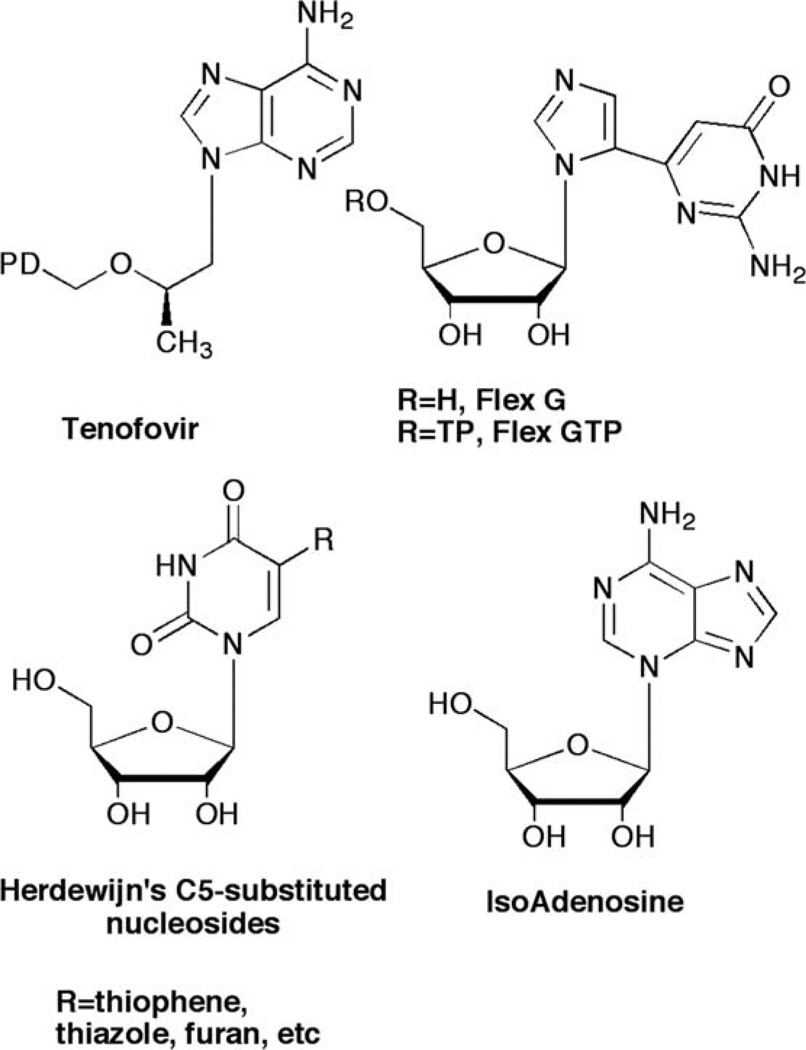

Ongoing investigations in our laboratories have focused on exploring the effects of nucleobase flexibility on enzyme affinity and viral resistance brought about by escape mutations increasingly common to enzymes involved in viral replication pathways. To date this strategy has provided several meaningful results for us and others. Most notably is the success of tenofovir (Fig. 1), a flexible HIV reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitor that has been shown to overcome viral resistance mechanisms due to the ability to “wiggle and jiggle” in the RT binding pocket.1–3

Fig. 1.

Flexible nucleoside leads.

From our own laboratory, a flexible guanosine nucleoside (Flex-G, Fig. 1), served as an inhibitor of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (SAHase), an adenosine-metabolizing enzyme.4 The flexibility of the nucleobase allowed the purine components to rotate and reposition to allow Flex-G to mimic adenosine.4,5 In addition to SAHase inhibition, it was also found that the triphosphate analogue of Flex-G was a significantly better substrate for GTP fucose pyrophosphorylase (GFPP) than the natural substrate GTP, and was able to retain full activity when key amino acid residues required for GTP recognition were mutated.6,7 Notably, GTP was rendered completely inactive.

To further explore the effects of flexibility on improving biological activity, we next envisioned a “reverse” connectivity for the split purine ring system. A search of the literature revealed some C5-substituted pyrimidine ribose analogues from Herdewijn et al. which were highly active against HSV-1 upon activation (phosphorylation) by the virus-encoded thymidine kinase (TK).8,9 Similarly, Greco and Tor have investigated some of the same nucleosides for use as fluorescent bioprobes to study DNA’s helical structure.10

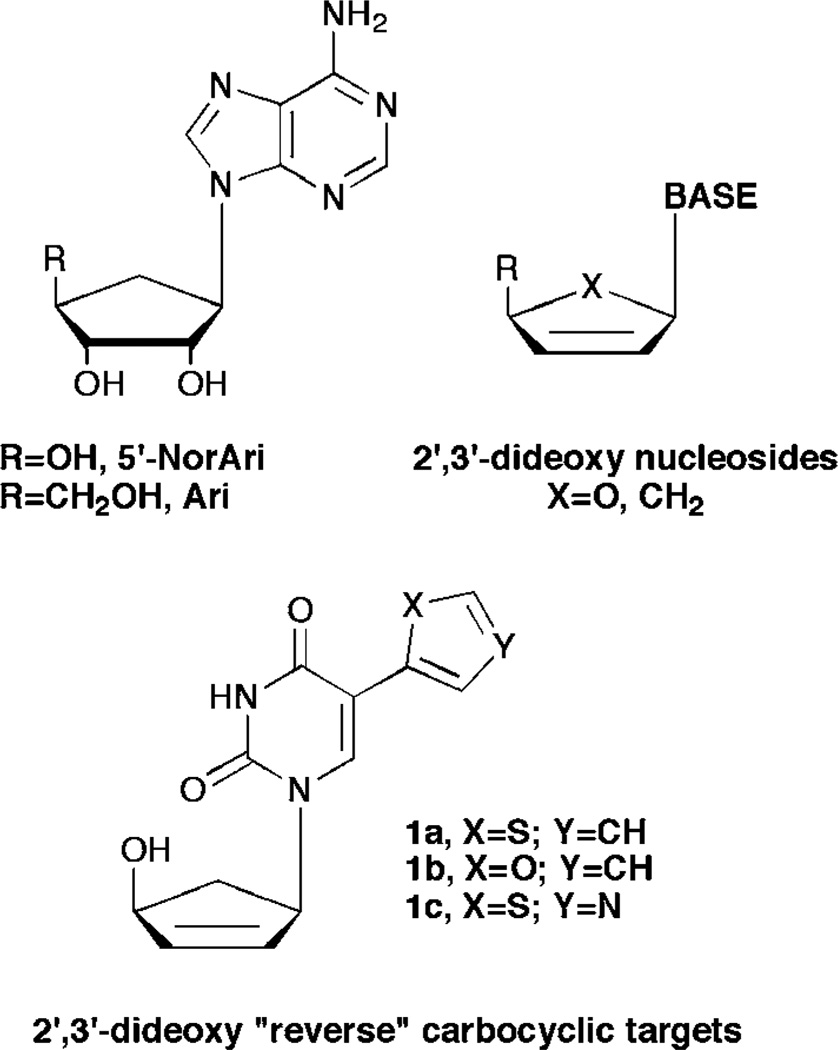

Turning to the leads provided by carbocyclic nucleoside inhibitors of SAHase, from our laboratories a series of carbocyclic purine analogues resembling Isoadenosine (IsoA, Fig.1)11–13 were designed (Fig. 2). Substituting a thiazole for the imidazole in the bicyclic ring imparted excellent SAHase activity for the N-3 glycosylated purine analogues.13 Taking this one step further, we decided to combine these leads with the significant activity exhibited by the 2′,3′-dideoxy and 5′-nor motifs. Nucleosides missing the 2′- and 3′-hydroxyls have shown activity as chain terminators in viral replication,14 while 5′-nor carbocyclic nucleosides have shown reduced cytotoxicity due to their resistance to phosphorylation, something that renders other potent SAHase inhibitors such as aristeromycin (Ari, Fig. 2) and neplanocin A (NpcA, Fig. 2) toxic.15,16

Fig. 2.

Carbocyclic leads and the target “reverse” fleximer compounds.

Thus, by combining the 5′-nor carbocyclic modifications known to be active against SAHase, with the flexibility of the nucleobase scaffold as with Herdewijn’s C-5 substituted alternative substrates for TK, it was hoped that the “reverse” carbocyclic fleximers would serve not only as inhibitors of purine metabolizing enzymes such as SAHase and adenosine deaminase, but also to be recognized by pyrimidine metabolizing enzymes, as well as to potentially serve as chain terminators.

Chemistry

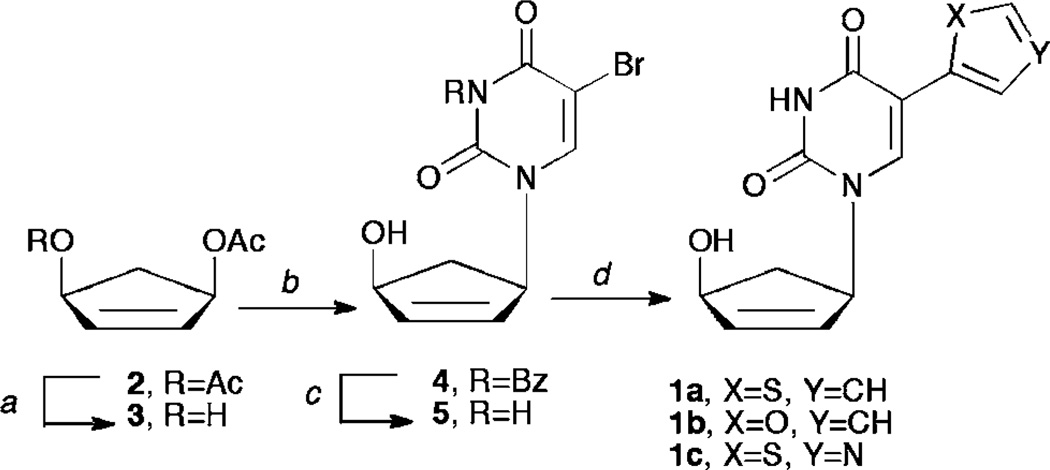

Construction of targets 1a–c was envisioned from a very facile and concise route based on several literature procedures. Starting from a known17 enantiomeric carbocyclic intermediate 3 (Scheme 1), a series of organometallic coupling procedures can be employed to provide the desired compounds. Moreover, the organotin heterocycles needed for coupling to the pyrimidine ring are commercially available or can be readily constructed using literature procedures.18,19 Although imidazole would have been a logical choice, we noted that Herdewijn had been unable to remove the methyl group on the imidazole nitrogen, and that ultimately it was inactive, thus we chose instead to focus on the thiophene, thiazole and furan pendant rings, especially since those had proven most active for him as well.

Scheme 1.

(a) Pseudomonas cepacia lipase, potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, acetone, 1 N NaOH; (b) NaH, DMF, Pd2(dba)3, DPPP, N3-benzoylated-5-bromouracil, 55 °C, 72 h; (c) methanolic ammonia, rt; (d) for 1a, tributylstannyl thiophene, dioxane, PdCl2(PPh3)2; for 1b, tributylstannyl furan, dioxane, PdCl2(PPh3)2; for 1c, tributylstannyl thiazole, THF, Pd(PPh3)4.

As shown in Scheme 1, enzymatic resolution of the meso-diacetate 2 with Pseudomonas cepacia lipase17 gives the desired enantiomer 3 needed for Trost coupling to the pyrimidine ring system. With 3 in hand, the N3-benzoyl protected pyrimidine base20 was added through the use of a palladium catalyzed Tsuji–Trost coupling.21 Intermediate 4 was then deprotected using mild basic conditions to yield compound 5, which was then subjected to Stille coupling9 with the organotin reagent and either PdCl2(PPh3)2 or Pd(PPh3)4 to yield compounds 1a–c. It should be noted that the thiazole derivative went in better yield using the Pd(PPh3)4 catalyst due to its altered electronics in comparison to the thiophene or furan derivatives.

Biological results

Broad antiviral testing of the candidate compounds was carried out. The candidates were evaluated for their potential inhibitory activity against herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, HSV TK−, vaccina virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, respiratory syncytial virus, Sindbis virus, Punta Toro virus, Reovirus-1, Coxsackie virus B4, parainfluenza-3 virus, influenza virus types A and B, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), and type 2 (HIV-2). Targets 1a–c showed no activity at subtoxic concentrations. Inhibitory activity against HCMV and VZV was observed for 1a at EC50’s of 1.6–2.0 µM, but 1a was also found to be cytotoxic in the lower micromolar range. Indeed, compound 1a exhibited global cytotoxicity at 4–20 µM against four different cell lines (HEL, HeLa, Vero, MDCK). The results of the assays have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antiviral and cytotoxic activity of test compounds in cell culture

| EC50a/µM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | 1a | 1b | 1c | Ribavirin | |

| HEL cells | |||||

| HSV-1 (KOS) | >4 | >100 | >100 | >250 | |

| HSV-1 TK− | >4 | >100 | >100 | >250 | |

| HSV-2 (G) | >4 | >100 | >100 | >250 | |

| VV | >4 | >100 | >100 | >250 | |

| VSV | >4 | >100 | >100 | 146 | |

| HCMV (AD-169 & Davis) | 1.8–2.0 | — | >20 | — | |

| VZV (OKA & 07/1) | 1.6–1.7 | — | 47–56 | — | |

| HeLa cells | |||||

| VSV | 4 | >100 | >100 | 29 | |

| Coxsackie virus B4 | >4 | >100 | >100 | 146 | |

| RSV | >4 | >100 | >100 | 10 | |

| CEM cells | |||||

| HIV-1(IIIB) HIV-2(ROD) | >2 | >100 | >50 | >50 | |

| Vero cells | |||||

| Parainfluenza-3 virus | >4 | >100 | >100 | 85 | |

| Reovirus-1 | >4 | 100 | >100 | >250 | |

| Sindbis virus | >4 | 100 | >100 | >250 | |

| Coxsackie virus B4 | >4 | >100 | >100 | >250 | |

| Punta Toro virus | >4 | 20 | >100 | 126 | |

| MDCK cells | |||||

| Influenza virus (AH3N2) | >0.8 | — | >20 | 9 | |

| Influenza virus A (H1N1) | >0.8 | — | >20 | 9 | |

| Influenza virus B | >0.8 | — | >20 | 9 | |

| Cell line | MCCb/µM | ||||

| HEL | ≥4 | >100 | ≥100 | >250 | |

| HeLa | 20 | >100 | >100 | >250 | |

| Vero | 20 | >100 | >100 | >250 | |

| MDCK | 4 | — | 100 | >100 | |

50% Effective concentration, or compound concentration required to inhibit virus-induced cytopathicity by 50%.

Minimal cytotoxic concentration, or compound concentration required to cause a microscopically visible alteration of cell morphology.

Summary

The synthesis of a series of 5′-nor-like carbocyclic “reverse” fleximer nucleosides was completed using enzymatic resolution as well as employing Trost and Stille coupling. Although initial testing of the compounds against SAHase and ADA showed no inhibitory activity, interestingly, in our laboratory we have observed ADA inhibition with other types of carbocyclic analogues possessing the same or similar base moieties (unpublished results), thus the lack of activity against purine metabolizing enzymes of the 2′,3′-dideoxy analogues could be due to the specific structural motif of the carbocycle.

Although none of the compounds were antivirally active at subtoxic concentrations, 1a had significant cytotoxic activity against several tumor cell lines. To explore this cytotoxicity 1a had been sent to NCI for additional testing in their cancer program and was unsuccessful in warranting additional testing. It is currently unclear whether the markedly higher toxicity of 1a than 1b and 1c is due to a direct and selective inhibitory activity of the compound as such against a currently as yet not defined cellular function, or whether compound 1a, but not 1b or 1c, has selectively been metabolized (i.e. phosphorylated) by a cellular enzyme to exert its cytotoxic activity.

Experimental

General

All chemicals were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Anhydrous DMF, MeOH, DMSO and toluene were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Anhydrous THF, acetone, CH2Cl2, CH3CN and ether were obtained using a solvent purification system (mBraun Labmaster 130). Melting points are uncorrected. NMR solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). All 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on a JEOL ECX 400 MHz NMR, operated at 400 and 100 MHz respectively, and referenced to internal tetramethylsilane (TMS) at 0.0 ppm. The spin multiplicities are indicated by the symbols s (singlet), d (doublet), dd (doublet of doublets), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet), and b (broad). Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using 0.25 mm Whatman Diamond silica gel 60-F254 precoated plates. Column chromatography was performed using silica gel (63–200 µ) from Dynamic Adsorptions Inc. (Norcross, GA), and eluted with the indicated solvent system. Yields refer to chromatographically and spectroscopically (1H and 13C NMR) homogeneous materials. Mass spectra were recorded at the Johns Hopkins Mass Spectrometry Facility (Baltimore, MD). Elemental analyses were recorded at Atlantic Microlabs, Inc. (Norcross, GA).

Preparation of 4-acetoxy-2-cyclopenten-1-ol (3)

To a stirred suspension of 2 (50 g, 270 mmol) in 0.2Mphosphate buffer (pH 7.2, 200 mL) and acetone (200 mL) was added Pseudomonas cepacia lipase (5 g) in one portion. The rapidly decreasing pH was maintained between 7.0 and 7.3 by the addition of aqueous NaOH (10.79 g, 270 mmol, in 200 mL H2O). After 3 h an additional portion of P. cepacia (3 g) was added. After the NaOH was consumed the reaction mixture was diluted with EtOAc (500 mL) and then filtered through a pad of celite. The aqueous layer was washed with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL) and the combined organic layers dried over MgSO4 and evaporated to dryness. The crude mixture was purified using silica gel chromatography eluting with hexanes : EtOAc (9 : 1) to give the product as a white crystalline solid (18.93 g, 130 mmol, 49%). Spectral data agreed with literature values.17

Preparation of 1-[4′-hydroxy-2′-cyclopenten-1′-yl]-5-bromouracil (5)

To a stirred suspension of NaH (1.33 g, 54.32 mmol) was added dropwise a solution of Bz-protected bromopyrimidine (13.36 g, 45.27 mmol) in DMSO (70 mL). After 30 min, a solution of Pd (PPh3)4 (1.0 g, 0.87 mmol), PPh3 (2.0 g, 7.62 mmol), and hydroxyacetate 3 (5.75 g, 40.98 mmol) in THF (300 mL) was added and the reaction mixture stirred at 55 °C for an additional 72 h. The reaction mixture was then cooled, evaporated to dryness and the crude product purified by silica gel chromatography eluting with hexanes : EtOAc (1 : 2) to give 4 as an off-white foam (4.85 g, 12.86 mmol, 31%, mp decomposes at 95 °C). 1HNMR(CDCl3) δ 1.67 (dt, 1H, J = 37.8, 16.0 Hz), 2.88 (m, 1H, J = 37.8, 18.3, 2.3 Hz), 4.87 (dd, 1H, J = 17.1, 5.7 Hz), 5.53 (dt, 1H, J = 21.8, 9.1 Hz), 5.87 (dd, 1H, J = 13.8, 4.6 Hz), 6.29 (dt, 1H, J = 18.3, 10.3 Hz), 7.50 (t, 2H, J = 39.0, 18.4 Hz), 7.65 (m, 1H, J = 36.7, 18.3 Hz), 7.86 (s, 1H), 7.91 (m, 2H, J = 29.8, 17.2 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 40.2, 60.5, 74.6, 96.9, 129.4, 130.7, 131.1, 135.5, 140.6, 141.3, 149.4, 158.2, 167.9, 181.2.

A stirred solution of 4 (2.13 g, 5.65 mmol) in methanolic ammonia (125 mL) was allowed to react for 3 h. The reaction mixture was co-evaporated from EtOH (3 × 10 mL) and the residue dissolved in EtOAc (25 mL). The organic solution was then washed with 1 N HCl (2 × 100 mL), brine (100 mL), dried over MgSO4 and evaporated to dryness. The crude residue was purified by silica gel chromatography eluting with hexanes : EtOAc (1 : 4) to give 5 as a white powder (1.20 g, 4.39 mmol, 77%, mp decomposes at 186.6 °C). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.60 (dt, 1H, J = 36.6, 17.2, 9.2 Hz), 2.80 (m, 1H, J = 36.7, 20.0, 3.5 Hz), 4.47 (bm, 1H, OH), 4.77 (d, 1H, J = 17.2 Hz), 5.51 (m, 1H, J = 9.2, 5.8, 3.4 Hz), 5.80 (qd, 1H, J = 13.7, 3.5, 2.3 Hz), 6.13 (dt, 1H, J = 13.7, 10.3 Hz), 7.80 (s, 1H), 11.74 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 39.9, 59.6, 73.9, 95.8, 130.8, 140.0, 141.9, 142.0, 160.4. HRMS calculated for C9H9BrN2O3 [M + H 79Br]+ 272.9872, [M + H 81Br]+ 274.4854; found: 272.9875, 274.9855.

Stille coupling conditions for stannyl thiophene and stannyl furan reagents

To a stirred solution of the desired 5-bromo carbocyclic nucleoside 5 (1 equivalent) and aryl tin (4 equivalents) in dioxane (50 mL) was added PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.1 equivalent) and the temperature held at 120 °C for 18 h. The reaction mixture was then evaporated to dryness and the residue purified by silica gel chromatography eluting with hexanes : EtOAc (1 : 1).

1-[4′-Hydroxy-2′-cyclopenten-1′-yl]-5-(thiophene-2-yl)-uracil (1a)

902 mg, 89% as an off-white solid; mp: decomposes at 146 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.50 (dt, 1H, J = 27.5, 16.1, 8.0 Hz), 2.70 (m, 1H, J = 27.5, 18.3, 3.4 Hz), 4.63 (bs, 1H, OH), 5.37 (d, 1H, J = 13.7 Hz), 5.45 (m, 1H, J = 12.6, 11.9, 11.4, 4.5 Hz), 5.87 (dd, 1H, J = 13.7, 3.4 Hz), 6.18 (dt, 1H, J = 13.7, 9.1, 3.4 Hz), 7.02 (dd, 1H, J = 12.6, 9.1 Hz), 7.28 (dd, 1H, J = 9.1, 3.4 Hz), 7.42 (dd, 1H, J = 12.6, 3.4 Hz), 7.97 (s, 1H), 11.62 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 40.60, 59.20, 73.81, 108.94, 123.01, 126.14, 127.00, 131.68, 134.63, 137.76, 140.75, 150.39, 161.83 (HMQC verified CH2 of the carbocycle at δ 40.60, but being masked by DMSO signal). HRMS calculated for C13H12N2O3S [M]+ 276.0567; found: 276.0567.

1-[4′-Hydroxy-2′-cyclopenten-1′-yl]-5-(furan-2-yl)-uracil (1b)

851 mg, 89% as an off-white hygroscopic solid; mp: decomposes at 140 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.42 (dt, 1H, J = 35.6, 20.7, 10.3 Hz), 2.72 (m, 1H, J = 35.6, 18.3, 4.6 Hz), 4.62 (bs, 1H, OH), 5.29 (d, 1H, J = 13.8 Hz), 5.44 (m, 1H, J = 10.3, 2.3 Hz), 5.85 (dd, 1H, J = 13.8, 2.3 Hz), 6.18 (dt, 1H, J = 13.8, 4.6 Hz), 6.49 (dd, 1H, J = 12.6, 8.0, 4.5 Hz), 6.82 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.60 (dd, 1H, J = 4.5, 2.3 Hz), 7.82 (s, 1H), 11.59 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 59.1, 73.8, 105.9, 108.3, 112.2, 131.2, 136.2, 141.2, 141.9, 146.9, 150.4, 160.7 (as with 1a and 1c the CH2 signal is masked by DMSO). HRMS calculated for C13H12N2O4 [M + H]+ 261.0875; found: 261.0874.

1-[4′-Hydroxy-2′-cyclopenten-1′-yl]-5-(thiazol-5-yl)-uracil (1c)

To a stirred solution of 5 (300 mg, 1.10 mmol) and 5-(tributylstannyl) thiazole (900 mg, 2.405 mmol) in dry THF (50 mL) was added Pd(PPh3)4 (50 mg) and refluxed under nitrogen for 72 h. The reaction mixture was then evaporated to dryness and the resulting residue purified by silica gel chromatography eluting with 5% EtOH in CH2Cl2 to give 1c (206 mg, 68%) as a hygroscopic white solid; mp: decomposes at 180.8 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.53 (dt, 1H, J = 35.6, 21.8, 11.4 Hz), 2.70 (m, 1H, J = 35.6, 18.3, 3.5 Hz), 4.63 (bs, 1H, OH), 5.36 (d, 1H, J = 13.7 Hz), 5.43 (m, 1H, J = 20.6, 18.3, 4.6 Hz) 5.88 (dd, 1H, J = 9.2, 3.5 Hz), 6.18 (m, 1H, J = 13.8, 4.6 Hz), 8.08 (s, 1H), 8.09 (s, 1H), 8.96 (s, 1H), 11.75 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 40.44, 59.40, 73.87, 106.16, 129.75, 131.60, 138.85, 139.10, 140.83, 150.41, 154.14, 161.77. HMQC verified CH2 of the carbocycle at δ 40.44, but being masked by DMSO signal. HRMS calculated for C12H11N3O3S [M + H]+ 278.0599; found: 278.0589.

Antiviral assays

The antiviral assays, other than the anti-HIV assays, were based on inhibition of virus-induced cytopathicity in HEL [herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (KOS), HSV-2 (G), vaccinia virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV)], Vero (parainfluenza-3, reovirus-1, Sindbis and Coxsackie B4), HeLa (vesicular stomatitis virus, Coxsackie virus B4, and respiratory syncytial virus) or MDCK [influenza A (H1N1; H3N2) and influenza B] cell cultures. Confluent cell cultures (or nearly confluent for MDCK cells) in microtiter 96-well plates were inoculated with 100 CCID50 of virus (1 CCID50 being the virus dose to infect 50% of the cell cultures) in the presence of varying concentrations (5-fold compound dilutions) of the test compounds. Viral cytopathicity was recorded as soon as it reached completion in the control virus-infected cell cultures that were not treated with the test compounds. The minimal cytotoxic concentration (MCC) of the compounds was defined as the compound concentration that caused a microscopically visible alteration of cell morphology. The methodology of the anti-HIV assays was as follows: human CEM (~3 × 105 cells per cm3) cells were infected with 100 CCID50 of HIV(IIIB) or HIV-2(ROD) per mL and seeded in 200 µL wells of a microtiter plate containing appropriate dilutions of the test compounds. After 4 days of incubation at 37 °C, HIV-induced CEM giant cell formation was examined microscopically.

For the VZV and HCMV assays, confluent human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts were grown in 96-well microtiter plates and infected with the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) strain, AD-169 and Davis at 100 PFU per well. After a 2 hour incubation period, residual virus was removed and the infected cells were further incubated with medium containing different concentrations of the test compounds (in duplicate). After incubation for 7 days at 37 °C, virus-induced cytopathogenicity was monitored microscopically after ethanol fixation and staining with Giemsa. Antiviral activity was expressed as the EC50 or compound concentration required to reduce virus-induced cytopathogenicity by 50%. EC50s were calculated from graphic plots of the percentage of cytopathogenicity as a function of concentration of the compounds.

The laboratory wild-type VZV strain Oka and the thymidine kinase-deficient VZV strain 07-1 were used for VZV infections. Confluent HEL cells grown in 96-well microtiter plates were inoculated with VZV at an input of 20 PFU per well. After a 2 h incubation period, residual virus was removed and various concentrations of the test compounds were added (in duplicate). Antiviral activity was expressed as EC50, or compound concentration required to reduce viral plaque formation after 5 days by 50% as compared with untreated controls.

Cytostatic/toxicity assays

Cytotoxicity was expressed as minimum cytotoxic concentration (MCC) or compound concentration that causes a microscopically detectable alteration of cell morphology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mrs Leentje Persoons, Mrs Frieda De Meyer, Mrs Leen Ingels, Mrs Lies Van den Heurck, Mrs Anita Camps and Mr Steven Carmans for excellent technical assistance. This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health Biomedical Research CBI Training grant T32GM066706 (KSR and SCZ). The antiviral assays were supported by a grant to K.U.Leuven (GOA no. 10/014).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and HRMS. See DOI: 10.1039/c1md00094b

References

- 1.Tuske S, Sarafianos SG, Clark AD, Jr, Ding J, Naeger LK, White KL, Miller MD, Gibbs CS, Boyer PL, Clark P, Wang G, Gaffney BL, Jones RA, Jerina DM, Hughes SH, Arnold E. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:469–474. doi: 10.1038/nsmb760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das K, Lewi PJ, Hughes SH, Arnold E. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2005;88:209–231. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das K, Bauman JD, Clark AD, Jr, Frenkel YV, Lewi PJ, Shatkin AJ, Hughes SH, Arnold E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:1466–1471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711209105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seley KL, Quirk S, Salim S, Zhang L, Hagos A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:1985–1988. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seley KL, Zhang L, Hagos A, Quirk S. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3365–3373. doi: 10.1021/jo0255476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quirk S, Seley KL. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13172–13178. doi: 10.1021/bi051288d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quirk S, Seley KL. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10854–10863. doi: 10.1021/bi0503605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Winter H, Herdewijn P. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:4727–4737. doi: 10.1021/jm960278v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wigerinck P, Pannecouque C, Snoeck R, Claes P, de Clercq E, Herdewijn P. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:2383–2389. doi: 10.1021/jm00112a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greco NJ, Tor Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10784–10785. doi: 10.1021/ja052000a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonard NJ, Laursen RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:2026–2028. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonard NJ, Laursen RA. Biochemistry. 1965;4:354–365. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadler JM, Mosley SL, Dorgan KM, Zhou ZS, Seley-Radtke KL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:5520–5525. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orr DC, Figueiredo HT, Mo CL, Penn CR, Cameron JM. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:4177–4182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marquez VE. Adv. Antiviral Drug Des. 1996;2:89–146. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daelemans D, Este JA, Witvrouw M, Pannecouque C, Jonckheere H, Aquaro S, Perno CF, De Clercq E, Vandamme AM. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:1157–1163. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.6.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siddiqi SM, Chen X, Schneller SW. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 1993;12:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinhey JT, Roche EG. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1988:2415–2421. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zambon A, Borsato G, Brussolo S, Frascella P, Lucchini V. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;49:66–69. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russ P, Schelling P, Scapozza L, Folkers G, Clercq ED, Marquez VE. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:5045–5054. doi: 10.1021/jm030241s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegde VR, Seley KL, Schneller SW. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2000;19:269–273. doi: 10.1080/15257770008033008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.