Abstract

While theorists have speculated that different affective traits are linked to reliable brain activity during anticipation of gains and losses, few have directly tested this prediction. We examined these associations in a community sample of healthy human adults (n = 52) as they played a Monetary Incentive Delay Task while undergoing functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI). Factor analysis of personality measures revealed that subjects independently varied in trait Positive Arousal and Negative Arousal. In a subsample (n = 14) retested over 2.5 years later, left nucleus accumbens (NAcc) activity during anticipation of large gains (+$5.00) and right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses (−$5.00) showed significant test-retest reliability (intraclass correlations > 0.50, p’s < 0.01). In the full sample (n = 52), trait Positive Arousal correlated with individual differences in left NAcc activity during anticipation of large gains, while trait Negative Arousal correlated with individual differences in right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses. Associations of affective traits with neural activity were not attributable to the influence of other potential confounds (including sex, age, wealth, and motion). Together, these results demonstrate selective links between distinct affective traits and reliably-elicited activity in neural circuits associated with anticipation of gain versus loss. The findings thus reveal neural markers for affective dimensions of healthy personality, and potentially for related psychiatric symptoms.

Keywords: reward, punishment, accumbens, insula, affect, FMRI

Introduction

Early experimental psychologists suspected that the foundations of temperament lay deep within the brain (Wundt, 1897; Pavlov, 1927; Eysenck, 1947; Gray, 1970), but lacked the tools to test their theories. This persisting gap between theory and measurement prompted Gordon Allport to prophesy: “…traits are cortical, subcortical, or postural dispositions having the capacity to gate or guide specific phasic reactions. It is only the phasic aspect that is visible; the tonic is carried somehow in the still mysterious realm of neurodynamic structure” (Allport, 1966).

The development of psychometric measures allowed researchers to infer both the reliability (i.e., temporal stability) and validity (i.e., relevance to behavior) of latent affective traits (Eysenck, 1947). Factor analysis of these measures typically yields two independent dimensions associated with recurrent and intense affective states of “Positive Arousal” (i.e., positive and aroused affective experiences such as “excitement,” which are associated with traits like extraversion) and “Negative Arousal” (i.e., negative and aroused affective experiences such as “anxiety,” which are associated with traits like neuroticism; Russell, 1980; Watson et al., 1999). These affective states may arise during anticipation of significant but uncertain outcomes (Knutson and Greer, 2008) in order to promote adaptive approach towards opportunities and avoidance of threats (Watson et al., 1999).

Neuroimaging techniques with the capacity to resolve second-to-second changes in deep brain activity (including functional magnetic resonance imaging, or FMRI) have rekindled interest in the deep neural substrates of affective traits (e.g., Canli, 2006). Linking affective traits to neural activity requires not only reliable psychometric measures, but also reliable neuroimaging data. Studies examining the test-retest reliability of FMRI data, however, have produced mixed results (Bennett and Miller, 2010) -- particularly with respect to reward-related activity (Fliessbach et al., 2010; Plichta et al., 2012).

Although some studies have explored links between reliably-assessed affective traits and brain activity, none have first established the stability of their neural measures. FMRI tasks such as the “Monetary Incentive Delay” (MID) Task typically elicit robust neural activity during anticipation of monetary gains and losses in individuals. Meta-analyses of FMRI studies using these types of incentive tasks indicate that anticipation of increasing monetary gains increases nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and anterior insula activity whereas anticipation of increasing monetary losses primarily increases anterior insula activity (Knutson and Greer, 2008; Liu et al., 2011; Diekhof et al., 2012). Further, NAcc activity correlates with self-reported positive aroused affective states in response to large gain cues, while anterior insula activity correlates with self-reported negative or general aroused affective states in response to large loss cues (e.g., Knutson et al., 2005; Samanez-Larkin et al., 2007).

These neuroimaging findings have inspired an Anticipatory Affect Model (Knutson & Greer, 2008), which posits that while anticipation of gains elicits positive aroused affect as well as activity in relevant neural circuits (such as the NAcc), anticipation of losses instead elicits negative aroused affect as well as activity in distinct neural circuits (such as the anterior insula). By extension, we sought to determine whether affective traits would also potentiate neural activity in circuits associated with affective states. Specifically, in the context of a MID task during FMRI acquisition, we predicted that: (1) trait Positive Arousal would be associated with stable individual differences in NAcc activity during anticipation of large gains; (2) trait Negative Arousal would be associated with stable individual differences in anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses; and (3) these associations would not depend on other individual difference confounds (e.g., sex, age, wealth).

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were initially recruited via a survey research firm to be ethnically and socioeconomically representative of San Francisco Bay Area residents. A community sample of 52 healthy right-handed native English-speaking adults (29 female; right-handed, mean age = 50 ± 16.5 SD; age range 21–75) participated in the first phase of data collection (Table 1). Subjects had no self-reported history of neurological or psychiatric disorders, and were not currently taking psychiatric or cardiac medications. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Stanford University School of Medicine. Beyond the 52 subjects included in the analysis, two additional subjects were excluded from further consideration due to excessive head motion (i.e., greater than 2 mm from one whole-brain acquisition to the next, both within and across runs), and a third was excluded for not completing the psychometric measures. In addition to $20.00 per hour payment for participating, additional payments were determined by the cumulative outcome of subjects’ performance on the Monetary Incentive Delay (MID) task (M = $21.00 ± SD $7.00). Subjects who completed the MID task comprised a subset of those recruited for a larger study of financial decision making across the lifespan involving other tasks and measures (Samanez-Larkin, Kuhnen, Yoo, & Knutson, 2010).

Table 1.

Subject demographics and behavior

| Test 1 (total) | Test 1 (only) | Test 1+Test 2 | Welch's t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (female) | 53 (29) | 38 (21) | 14 (8) | 0.11 |

| Age (years) | 50 ± 16.5 | 52 ± 16.0 | 41 ± 12.2 | 2.69* |

| Hit Rate (%) | ||||

| +$5.00 | 63.97 ± 0.06 | 64.91 ± 0.05 | 67.62 ± 0.04 | −1.85 |

| +$0.50 | 63.72 ± 0.07 | 65.44 ± 0.07 | 63.81 ± 0.09 | 0.63 |

| +$0.00 | 62.82 ± 0.06 | 63.33 ± 0.07 | 63.81 ± 0.10 | −0.18 |

| −$0.00 | 62.56 ± 0.07 | 62.81 ± 0.08 | 62.86 ± 0.11 | −0.03 |

| −$0.50 | 65.26 ± 0.07 | 65.09 ± 0.07 | 65.24 ± 0.04 | −0.07 |

| −$5.00 | 63.97 ± 0.11 | 64.04 ± 0.12 | 63.33 ± 0.04 | 0.30 |

| Hit Reaction Time (ms) | ||||

| +$5.00 | 193.47 ± 21.03 | 195.68 ± 22.91 | 181.91 ± 13.97 | 2.61* |

| +$0.50 | 196.28 ± 21.45 | 198.48 ± 23.39 | 183.03 ± 20.19 | 2.34* |

| +$0.00 | 206.76 ± 24.69 | 209.36 ± 26.68 | 191.91± 26.01 | 2.13* |

| −$0.00 | 208.74 ± 27.32 | 213.04 ± 27.50 | 195.36 ± 21.78 | 2.41* |

| −$0.50 | 198.47 ± 25.14 | 200.45 ± 27.66 | 184.05 ± 16.18 | 2.63* |

| −$5.00 | 193.14 ± 21.02 | 195.19 ± 23.67 | 182.65 ± 15.71 | 2.20* |

| Traits (factor scores) | ||||

| Positive Arousal | −0.08 ± 0.98 | 0.22 ± 1.04 | −0.95 | |

| Negative Arousal | −0.05 ± 0.97 | 0.13 ± 1.10 | −0.53 |

p < 0.05, uncorrected

A representative subset of 14 subjects from the full sample (8 female; right-handed, mean age = 41 ± 12.17 years; age range 24–70) returned for a second experimental session over 2.5 years after the first scan (mean = 922 ± 49 days). Written informed consent was again obtained from these subjects. As before, in addition to $20.00 per hour payment for participation, additional payment was determined by the cumulative outcome of the MID task (M = $23.00 ± SD $5.00). Beyond the 14 subjects included in this analysis, one additional subject was excluded due to changes in medication status during the retest interval. Possibly due to the long delay, retested subjects were slightly younger than the rest of their cohort, but performed similarly (albeit slightly faster) on the experimental task during the retest session, and critically, did not differ with respect to affective traits (Table 1).

Affective trait measures

Subjects completed self-report measures of affective traits during the first experimental session, including the Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Five Factor Inventory (NEO – FFI; 60 items; McCrae & Costa, 2004), the Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Activation Scale (BIS/BAS; 20 items; (Carver & White, 1994)), and the Affect Valuation Index (AVI; 56 items; (Tsai, Knutson, & Fung, 2006)). Exploratory statistical analyses confirmed that no subject’s responses deviated more than three standard deviations from the average group response. Standard subscales were derived from E measure. “Extraversion” and “neuroticism” scores from the NEO-FFI, “actual high-arousal positive” and “actual high-arousal negative” scores from the AVI, and “behavioral inhibition,” “behavioral activation-reward,” “behavioral activation-drive,” and “behavioral activation-fun” scores from the BIS/BAS scales were submitted to a principal components analysis with an orthogonal varimax rotation. A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the combined subscale scores of all measures to verify that their correlation structure yielded two independent affective factors. To ensure independence while minimizing corrections for multiple hypothesis tests in subsequent analyses, factor loadings on derived “Positive Arousal” and “Negative Arousal” dimensions were then used to index affective traits for each individual.

Monetary Incentive Delay task

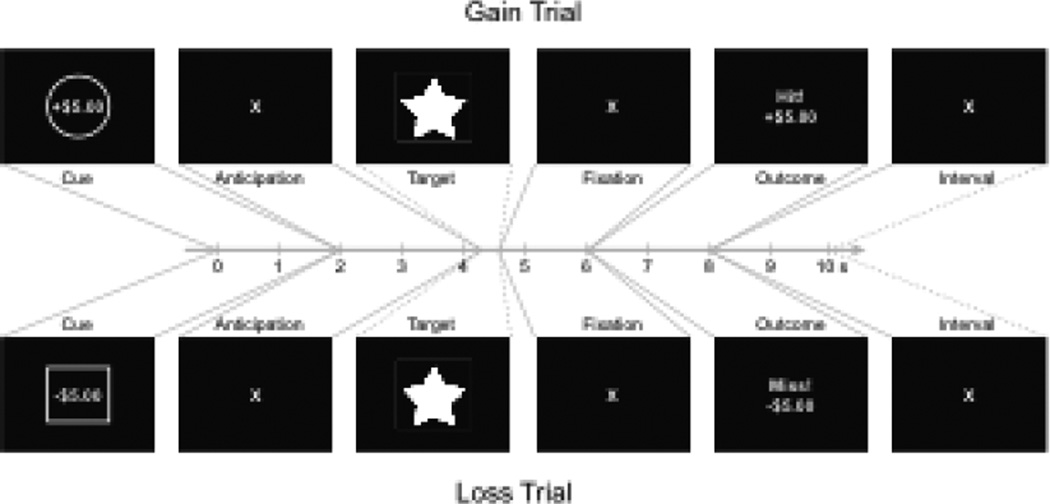

During each testing session, subjects participated in a slightly modified version of the Monetary Incentive Delay (MID) task (i.e., with a 2 (valence) × 3 (magnitude) factorial structure) while being scanned with FMRI (Figure 1). To accommodate older subjects, this version of the MID task included literal rather than symbolic cues and verbal as well as numerical notification of the outcome on each trial (i.e., the words “Hit!” or “Miss!”; Samanez-Larkin et al., 2007). Subjects received spoken and written instructions and then completed a brief practice session before beginning the experimental session in the scanner. During each task trial, subjects first viewed one of six types of cues indicating a combination of incentive valence (gain, loss) and magnitude (±$5.00, ±$0.50, ±$0.00; 2000 msec). This was followed by a fixation cross (2000–2500 msec; “anticipation” phase), after which a target was rapidly presented on the screen (~150–500 msec). If the subject pressed the button before target offset, they either gained or avoided losing the cued amount of money. Feedback indicating the trial outcome was then presented (2000 msec; “outcome” phase). Trials were separated by a variable intertrial interval (2000–6000 msec). 15 repetitions of each of the 6 trial types were presented in fully randomized order for each individual, summing to a total of 90 trials. Hit rate was targeted at 66% for each subject by an algorithm that adaptively changed target durations based on past performance within each condition. Individual functional volume acquisitions were time-locked to presentation of cues and outcomes using a temporal drift correction algorithm. Behaviorally, hit rate was calculated as percentage hits versus misses for each condition, and mean reaction time was calculated as the average hit reaction time in each condition minus the average hit reaction time across all conditions within each subject (to parallel brain activity measures in confound analyses, see Table 6).

Figure 1. Representative Monetary Incentive Delay task trials.

During each trial, subjects first saw a cue indicating potential gain or loss of different amounts (2 sec), next watched a fixation cross as they waited a variable delay (2–2.5 sec), next responded with a button press to a rapidly presented target of variable duration (160–260 msec), and finally saw the outcome of their action, depending on the cue presented and their success at responding before the target's disappearance (1.5–2.0 sec). Trials were separated by a variable intertrial interval (2–6 sec).

Table-6.

Associations of reliable neural activity and affective traits with potential individual difference confounds

| L NAcc (+$5.00) |

PA | R Ant Insula (–$5.00) |

NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.24 | −0.17 | −0.46* | −0.21 |

| Sex (men vs. women) | −0.21 | −0.25 | −0.09 | −0.28* |

| Wealth (debt/assets) | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Motion (average SD) | −0.12 | 0.02 | −0.17 | −0.09 |

| Reaction time (+$5.00) | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.09 |

| Reaction time (−$5.00) | −0.11 | −0.26 | −0.19 | −0.10 |

p < 0.05, uncorrected

L = left, R = right

Bold associations are predicted.

FMRI Acquisition and Analysis

Functional magnetic resonance images were acquired with a 1.5-T General Electric magnetic resonance scanner using a standard quadrature head coil (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI). Twenty-four contiguous axial 4-mm-thick slices (in-plane resolution, 3.75 by 3.75 mm; no gap) were acquired extending from the mid-pons to the crown of the skull. Functional scans were acquired with a T2*-sensitive spiral in/out pulse sequence designed to minimize signal dropout at the base of the brain (repetition time = 2 s, echo time = 40 ms, flip = 90 degrees; Glover & Law, 2001). High resolution structural scans for localization and coregistration of functional data were acquired with a T1-weighted spoiled grass sequence (repetition time =100 ms, echo time = 7 ms, flip = 90 degrees).

Based on previous meta-analytic findings (Knutson & Greer, 2008), analyses specifically focused on peak activity in three bilateral brain regions (right and left NAcc, anterior insula, and MPFC) across the six conditions (±$5.00, ±$0.50, ±$0.00) and two task phases (anticipation and outcome). Analyses of neural data utilized Analysis of Functional Neurolmages software (Cox, 1996). For preprocessing, voxel time series were corrected for non-simultaneous slice acquisition using sine interpolation, concatenated across runs, and corrected for three-dimensional motion using sine interpolation. Visual inspection of motion correction estimates confirmed that no subject’s head moved more than 2 mm in any direction from one volume acquisition to the next (either within or across runs). Data were then slightly spatially smoothed (FWHM = 4 mm) and high-pass filtered within runs (to omit frequencies longer than 90 s). Finally, percentage signal change was calculated for each voxel at each time point with respect to mean activation in that voxel over the entire task (and thus, over all conditions and trial phases).

Analyses of FMRI data included both whole-brain and volume of interest approaches. For whole brain analysis, preprocessed time series data for each individual were analyzed with a multiple regression model that included four orthogonal regressors of interest: (1) gain (+$5.00, +$0.50) versus nongain (+$0.00) anticipation; (2) loss (−$5.00, −$0.50) versus nonloss (−$0.00) anticipation; (3) “hit” (+$5.00, +$0.50) versus “miss” (+$0.00) gain outcomes; (4) and “hit” (−$0.00) versus “miss” (−$5.00, −$0.50) loss outcomes. Additional covariates included two orthogonal regressors highlighting the periods of interest (i.e., anticipation and outcome), six regressors describing residual motion, and six regressors modeling baseline, linear, and quadratic trends for each of two task runs. Regressors of interest contrasted activity during predicted periods (2 sec each), and were convolved with a single gamma-variate function that modeled a prototypical hemodynamic response (Cohen, 1997). No acquired brain volumes were excluded from analysis. Maps of t-statistics representing each of the regressors of interest were transformed into z-scores, and spatially normalized by warping to Talairach space. Global statistical thresholds were set at p < 0.001 (uncorrected) and required a cluster of 16 contiguous 2-mm3 voxels (i.e., the minimum cluster criterion for p < 0.05 whole-brain corrected threshold as specified by AFNI’s AlphaSim).

To test the predicted associations, volumes of interest were specified as 8-mm diameter spheres centered on predicted foci derived from a meta-analysis in the NAcc (x = ±10, y = 10, z = −2), anterior insula (x = ±33, y = 23, z = −4), and MPFC (x = ±5, y = 45, z = 0) (Knutson & Greer, 2008). Peak percentage signal change was averaged within each volume of interest, extracted, and then averaged by trial type. Peak percentage signal change was first tested for reliability in the subsample and then regressed against affective trait variables in the full sample.

Stability of neural responses

To assess the stability of neural responses across time, two sets of intraclass correlation coefficients (or ICC) were calculated (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979; Specht et al., 2003). To test the critical predictions, a first set of intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated on average peak activity for each condition extracted from volumes of interest. To compare these results with more traditional measures (Bennett & Miller, 2010), a second set of intraclass correlation coefficients was calculated on modeled activity contrasts between incentive (i.e., gain, loss) and nonincentive (i.e., nongain, nonloss) conditions from the same volumes of interest. Both single and average measures of intraclass correlation were calculated (i.e., ICC(3,1)). To minimize penalties for testing multiple predictions, subsequent validation analyses specifically focused on neural activity in conditions and regions that achieved moderate or greater test-retest reliability.

Validity of neural responses

Individual differences in trait Positive Arousal were correlated with NAcc activation during anticipation of large gains, and individual differences in Negative Arousal were correlated with anterior insula activation during anticipation of large losses. To verify specificity, individual differences in trait Positive Arousal were correlated with anterior insula activation during anticipation of large losses and individual differences in trait Negative Arousal were correlated with NAcc activation during anticipation of large gains. Further, individual differences in affective traits were correlated with medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) activity during anticipation of gains and losses, since the MPFC typically shows more robust activity during the outcome rather than the anticipation phase of the MID task.

To rule out alternative individual difference accounts, sex, age, wealth, and average movement were correlated with stable neural responses. In the event of a significant association, potential individual difference confounds were included in secondary regression analyses to determine whether they could account for primary associations between affective traits and stable neural responses. Significance thresholds for directional predicted associations between Positive Arousal and NAcc activity during anticipation of large gains and between Negative Arousal and Anterior Insula activity during anticipation of large losses (p < 0.05) were divided by two (p < 0.025) to allow separate consideration of neural activity in right and left volumes of interest.

To statistically test a double dissociation account of selective links between brain activity and affective traits, we used structural equation modeling (lavaan package for R software; Rosseel, 2012). Structural equation modeling allows investigators to simultaneously test for the presence or absence of multiple predicted associations. We specified two models: a fully connected model in which both NAcc and anterior insula activity correlated with both Positive Arousal and Negative Arousal traits, and a second reduced model in which NAcc activity only correlated with the Positive Arousal trait, and anterior insula activity only correlated with the Negative Arousal trait. We predicted that both models would fit the data, but that the full model would show that only paths from NAcc activity to Positive Arousal and from anterior insula activity to Negative Arousal were significant, and therefore, that the reduced model would fit the data as well as or better than the full model.

Power

A first power analysis for detecting group effects in NAcc activity was based on peak activity in response to +$5.00 versus +$0.00 cues in the context of the MID task (Knutson et al., 2005). For the large reported effect size (f2 = 3.07), at least 6 subjects are required to detect group effects at a power of .80 (p < 0.05). A second power analysis for detecting individual difference effects in NAcc activity was based on average intraclass correlation coefficient estimates of responses to +€2.00 versus +€0.00 cues in a similar reward anticipation task (Plichta et al., 2012). For the moderate reported effect size (average ICC = .59; f2 = 0.54), at least 13 subjects are required to detect individual differences at a power of .80 (p < 0.05, directional). Further, a previous meta-analysis reported that most test-retest analyses of FMRI data include an average of 11 subjects (Bennett & Miller, 2010). Thus, our test-retest sample of 14 was deemed sufficient for assessing the stability of individual differences in predicted neural responses over time.

Results

Overall, analyses aimed: (1) to verify robust group effects in predicted brain regions; (2) to demonstrate the temporal stability of neural responses in predicted brain regions; and (3) to establish selective associations of affective trait measures with stable responses in predicted brain regions.

Affective Trait Psychometrics

As predicted, two independent recovered principle components accounted for most of the variance in the affective trait measures (Total: 63.27%; Positive Arousal: 34.95%; Negative Arousal: 28.16%), and were the only factors with eigenvalues greater than one (Table 2). Individual scores on these independent “Positive Arousal” and “Negative Arousal” meta-traits were used to index affective traits in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Factor loadings for personality subscales

| Subscale | Positive Arousal | Negative Arousal |

|---|---|---|

| BAS-Reward | 0.77 | − |

| BAS-Drive | 0.75 | − |

| NEO-Extraversion | 0.75 | −0.47 |

| BAS-Fun | 0.74 | − |

| High Arousal Positive Affect | 0.67 | −0.45 |

| NEO-Neuroticism | - | 0.83 |

| High Arousal Negative Affect | - | 0.78 |

| BIS | - | 0.61 |

| Explained Variance | 34.95% | 28.32% |

Bold associations are predicted.

MID Task Behavior

Subjects approximated the targeted hit rate (66%) on both repetitions of the MID task (Table 1), hitting on 63.7% (Session 1) and 64.4% (Session 2) of all trials, and a repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant effects of trial type on hit rate in either session (F(1,51) = 0.19, p > 0.05; F(1,13) = 0.86, p > 0.05). A repeated-measures ANOVA indicated a main effect of incentive magnitude on hit reaction times in both sessions (F(2,50) = 17.15, p < 0.001; F(2,12) = 7.53, p > 0.01), indicating that subjects generally responded more rapidly to incentive cues (±$0.50 and ±$5.00) than to nonincentive cues (±$0.00; all p values < 0.01). Responses to gains versus losses did not differ, since pairwise comparisons revealed no significant differences in hit reaction times to gain versus loss incentives of the same magnitude (all p > 0.05; Table 1).

Neural responses to incentives

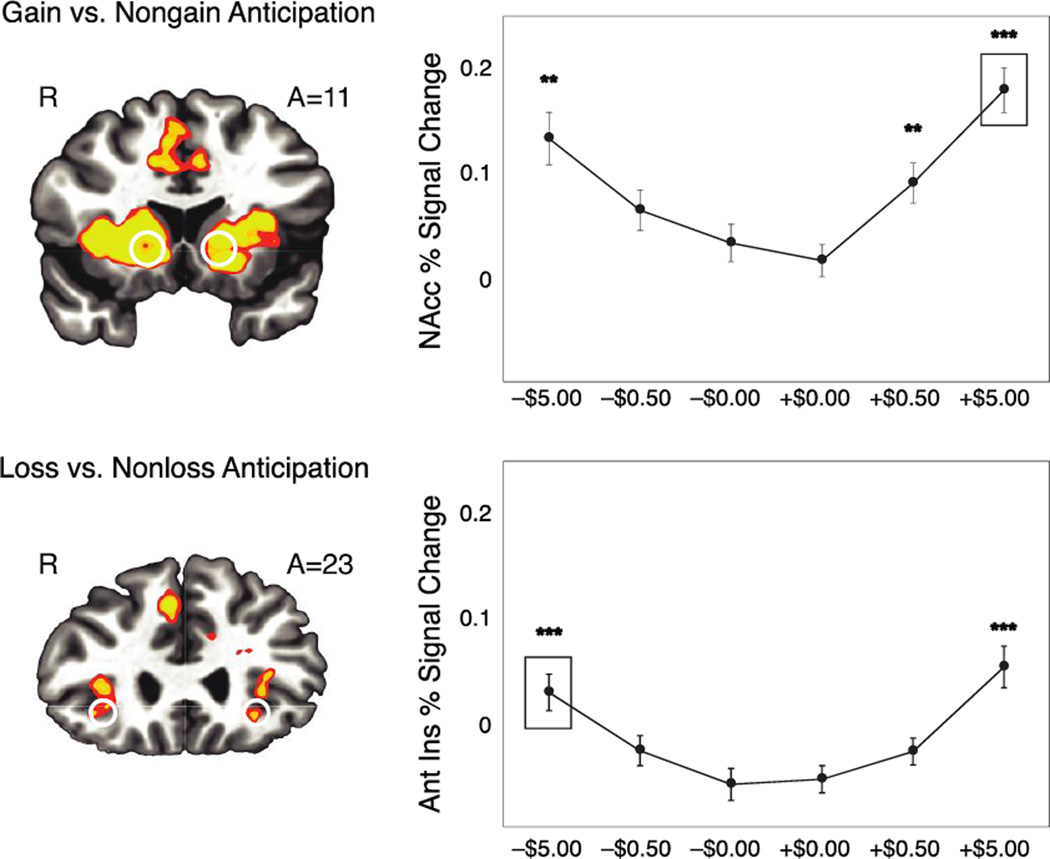

Consistent with previous whole brain analyses of MID task data (Knutson and Greer, 2008), the contrast of gain versus nongain anticipation activated bilateral NAcc (TC: 10, 15, −3; peak Z = 6.44 and TC: −15, 17, −5, peak Z = 6.70), while loss versus nonloss anticipation activated bilateral anterior insula (TC: 37, 11, 10; peak Z = 6.37 and peak TC: −33, 20, 12; Z = 5.99) (Figure 2). The contrast of “hit” versus “miss” gain outcomes activated MPFC (TC: −7, 45, 0; peak Z = 5.85) and “hit” versus “miss” loss outcomes activated bilateral putamen (TC: 25, 9, −2; peak Z = 6.24 and TC: −19, 9, −10; peak Z = 5.59). All of these activation foci were subsumed under the largest and most significant clusters activated by each contrast (additional foci are listed in Table 3).

Figure 2. MID Task, group activation contrasts, volumes of interest, and peak activation profiles.

Group contrast maps for gain versus nongain anticipation in the NAcc (top left panel) and loss versus nonloss anticipation in the anterior insula (bottom left panel). Mean (±SEM) peak percent signal change during anticipation was extracted from NAcc and anterior insula volumes of interest, averaged by condition (over 15 trials per condition), and plotted (right panels). Anticipation of large gains (+$5.00; p <.001), as well as small gains (+$0.50; p <.01) and large losses (−$5.00; p <.01), increased activity relative to anticipation of no outcome in the NAcc. Anticipation of large losses (−$5.00; p <.001) and gains (+$5.00; p <.001) increased activity relative to anticipation of no outcome in the anterior insula.

Table 3.

Whole brain activity during the Monetary Incentive Delay task (n=52)

| Contrast | Region | x | y | z | Peak Z | Voxels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gain vs. | ||||||

| Nongain | ||||||

| Anticipation | ||||||

| L Superior Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −17 | 51 | −12 | 4.78 | 198 | |

| L Middle Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −47 | 19 | 32 | 3.95 | 19 | |

| R Thalamus | 11 | −3 | 8 | 8.13 | 48240 | |

| L Anterior Insula | −30 | 21 | 10 | 6.22 | [SVC] | |

| R Anterior Insula | 33 | 15 | 6 | 7.33 | [SVC] | |

| R NAcc | 10 | 15 | −3 | 6.44 | [SVC] | |

| L NAcc | −15 | 17 | −5 | 6.70 | [SVC] | |

| R Caudate | 12 | 17 | 5 | 6.64 | [SVC] | |

| L Caudate | −16 | 15 | 3 | 6.67 | [SVC] | |

| R Putamen | 24 | 7 | −1 | 7.25 | [SVC] | |

| L Putamen | −15 | 11 | −4 | 6.70 | [SVC] | |

| L Transverse | ||||||

| Temporal Gyrus | −53 | −19 | 10 | 4.99 | 83 | |

| R Transverse | ||||||

| Temporal Gyrus | 51 | −25 | 12 | 3.80 | 41 | |

| R Middle | ||||||

| Temporal Gyrus | 47 | −31 | −8 | 5.03 | 99 | |

| R Superior | ||||||

| Temporal Gyrus | 65 | −33 | 16 | 4.07 | 86 | |

| L Fusiform Gyrus | −41 | −37 | −20 | 3.83 | 24 | |

| L Cerebellar | ||||||

| Tonsil | −15 | −37 | −30 | 3.84 | 22 | |

| L Fusiform Gyrus | −55 | −39 | −22 | 3.96 | 20 | |

| R Posterior | ||||||

| Cingulate | 19 | −53 | 20 | 3.97 | 47 | |

| R Middle | ||||||

| Temporal Gyrus | 47 | −61 | 2 | 3.99 | 37 | |

| Loss vs. | ||||||

| Nonloss | ||||||

| Anticipation | ||||||

| R Superior | ||||||

| Frontal Gyrus | 19 | 51 | −10 | 3.94 | 65 | |

| R Superior | ||||||

| Frontal Gyrus | 31 | 43 | 16 | 3.77 | 21 | |

| L Middle Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −23 | 17 | 34 | 3.94 | 30 | |

| L Inferior Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −51 | 7 | 18 | 4.40 | 47 | |

| R Precentral | ||||||

| Gyrus | 51 | 1 | 12 | 4.22 | 33 | |

| Midbrain | −1 | −17 | −16 | 6.54 | 43550 | |

| R Anterior Insula | 37 | 11 | 10 | 6.37 | [SVC] | |

| R Caudate | 12 | 4 | 12 | 6.48 | [SVC] | |

| L Caudate | −9 | 3 | 14 | 6.50 | [SVC] | |

| L Anterior Insula | −33 | 20 | 12 | 5.99 | [SVC] | |

| L NAcc | −13 | 17 | −3 | 6.04 | [SVC] | |

| R Putamen | 19 | 15 | −4 | 6.34 | [SVC] | |

| L Putamen | −19 | 15 | −3 | 5.59 | [SVC] | |

| R Putamen | 31 | −25 | 0 | 3.83 | 31 | |

| R Fusiform Gyrus | 43 | −25 | −16 | 3.67 | 20 | |

| L Cingulate Gyrus | −5 | −27 | 28 | 4.00 | 27 | |

| L Superior | ||||||

| Temporal Gyrus | −57 | −41 | 8 | 4.17 | 20 | |

| L Inferior | ||||||

| Temporal Gyrus | −59 | −51 | −8 | 4.23 | 29 | |

| R Posterior | ||||||

| Cingulate | 27 | −57 | 10 | 4.52 | 101 | |

| L Fusiform Gyrus | −51 | −63 | −16 | 3.57 | 17 | |

| Gain vs. | ||||||

| Nongain | ||||||

| Outcome | ||||||

| L Medial | ||||||

| Prefrontal | ||||||

| Cortex | −7 | 45 | 0 | 5.85 | 1036 | |

| R Inferior Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | 53 | 23 | 4 | −4.24 | 60 | |

| R Middle Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | 25 | 23 | 42 | 4.05 | 17 | |

| L Middle Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −23 | 19 | 44 | 4.87 | 273 | |

| L Inferior Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −45 | 13 | −2 | −3.72 | 37 | |

| R NAcc | 11 | 11 | −6 | 5.35 | 390 | |

| R Putamen | 26 | 10 | 0 | 4.20 | [SVC] | |

| L NAcc | −7 | 10 | −6 | 4.99 | [SVC] | |

| L Putamen | −14 | 7 | −8 | 5.17 | [SVC] | |

| R Parahipp. | ||||||

| Gyrus | 39 | −29 | −18 | 4.47 | 46 | |

| R Hippocampus | 35 | −29 | −8 | 4.11 | 36 | |

| L Hippocampus | −29 | −31 | −10 | 4.71 | 31 | |

| R Inferior Parietal | ||||||

| Lobule | 61 | −39 | 28 | −4.52 | 60 | |

| L Cingulate Gyrus | −5 | −41 | 28 | 4.00 | 22 | |

| L Middle | ||||||

| Temporal Gyrus | −59 | −45 | −14 | 4.44 | 62 | |

| L Calcarine Gyrus | −5 | −59 | 10 | 3.78 | 24 | |

| L Precuneus | −29 | −65 | 32 | 3.96 | 27 | |

| L Fusiform Gyrus | −17 | −69 | −12 | 3.96 | 23 | |

| R Precuneus | 35 | −71 | 34 | 3.97 | 48 | |

| L Angular Gyrus | −33 | −75 | 30 | 4.37 | 155 | |

| Nonloss vs. | ||||||

| Loss | ||||||

| Outcome | ||||||

| L Medial Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −3 | 57 | 14 | 3.82 | 61 | |

| L Superior Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −15 | 45 | 36 | 4.13 | 34 | |

| L Middle Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −19 | 43 | −10 | 5.07 | 184 | |

| R Middle Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | 35 | 37 | 28 | 3.85 | 46 | |

| L Middle Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −43 | 35 | 28 | 5.12 | 442 | |

| L Middle Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −21 | 21 | 54 | 4.51 | 91 | |

| L Putamen | −19 | 9 | −10 | 5.59 | 791 | |

| L Caudate | −20 | −16 | 22 | 4.75 | [SVC] | |

| R Putamen | 25 | 9 | −2 | 6.24 | 359 | |

| L Medial Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −9 | 9 | 48 | 4.19 | 20 | |

| L Middle Frontal | ||||||

| Gyrus | −51 | 7 | 40 | 3.96 | 55 | |

| R Putamen | 23 | 7 | 12 | 4.45 | 45 | |

| L Cingulate Gyrus | −7 | −3 | 36 | 4.21 | 56 | |

| R Precentral | ||||||

| Gyrus | 31 | −7 | 50 | 4.00 | 16 | |

| L Precentral | ||||||

| Gyrus | −37 | −13 | 50 | 3.79 | 16 | |

| R Cingulate | ||||||

| Gyrus | 9 | −17 | 42 | 4.01 | 24 | |

| R Paracentral | ||||||

| Lobule | 3 | −33 | 56 | 5.17 | 908 | |

| R Fusiform Gyrus | 45 | −33 | −14 | 5.18 | 53 | |

| L Parahipp. Gyrus | −33 | −33 | −12 | 3.92 | 49 | |

| L Precuneus | −7 | −33 | 46 | 3.81 | 16 | |

| L Middle | ||||||

| Temporal Gyrus | −63 | −41 | −8 | 4.04 | 18 | |

| L Inferior Parietal | ||||||

| Lobule | −49 | −51 | 46 | 4.37 | 209 | |

| L Superior | ||||||

| Parietal Lobule | −25 | −57 | 54 | 3.71 | 21 | |

| L Precuneus | −7 | −59 | 40 | 4.01 | 27 |

n = 52; p < 0.001; 16 2 mm voxel cluster threshold

Bold associations are predicted.

Stability of neural responses

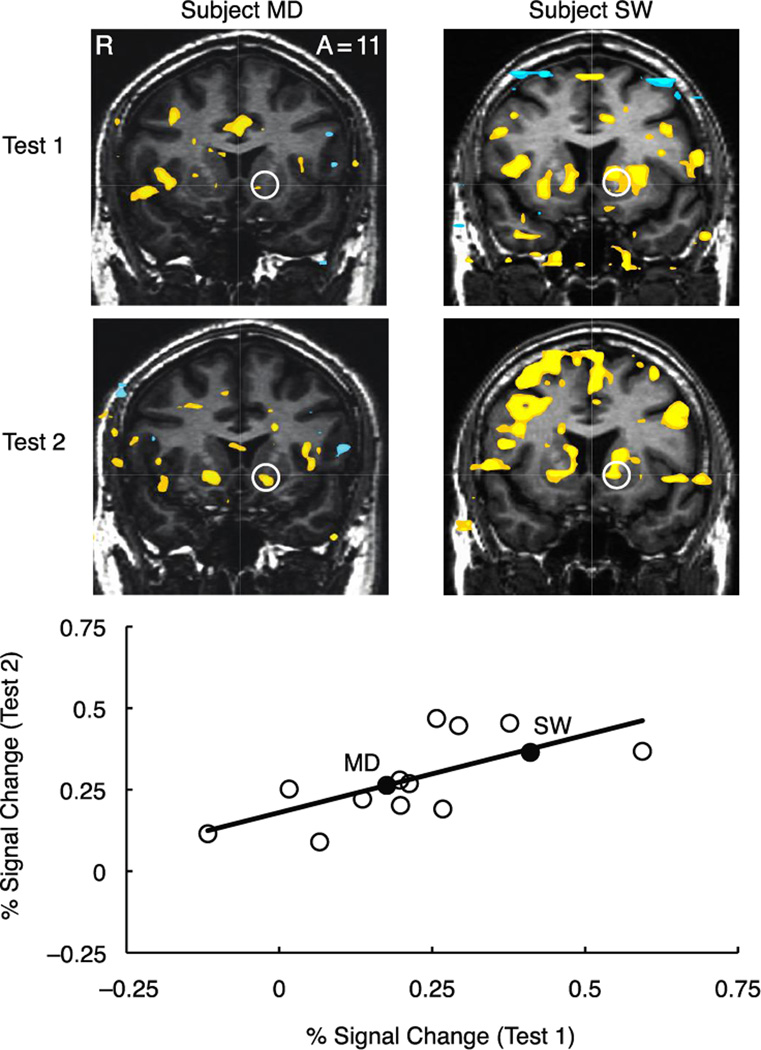

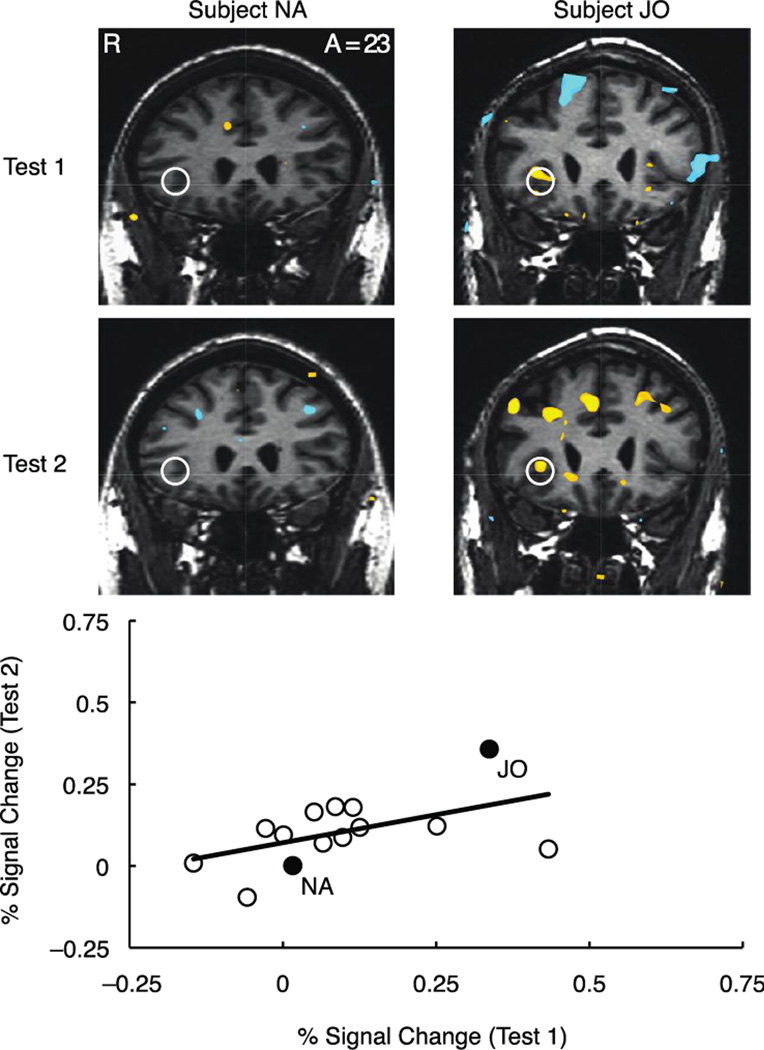

Temporal stability of anticipatory peak activity in the right and left NAcc, anterior insula, and MPFC was examined for each task condition (i.e., valence (gain, loss) by magnitude (±$5.00, ±$0.50, ±$0.00)) in each volume of interest in the subsample of retested subjects (n = 14) over a test-retest interval of greater than 2.5 years (Table 4). Analyses of regional activity focused on the maximally reliable peak anticipatory signal in each volume of interest (i.e., at anticipatory delay onset (6 sec lag) for NAcc and MPFC, but at cue onset (4 sec lag) for anterior insula). Left NAcc activity showed moderate to strong test-retest reliability during anticipation of large gains (+$5.00 ICC (single/average) = 0.64/0.78, p < 0.01) while right NAcc activity showed moderate test-retest reliability during anticipation of large gains (+5.00 ICC = 0.47/0.64, p < 0.05), as well as nongains (+0.00 ICC = 0.47/0.64, p < 0.05). Right anterior insula activation showed moderate test-retest reliability during anticipation of large losses (−$5.00 ICC = 0.47/0.64, p < 0.05) and medium losses (−$0.50 ICC = 0.63/0.77, p < 0.01), as well as during anticipation of large gains (+5.00 ICC = 0.48/0.64, p < .05), but left anterior insula activity was not reliable in any condition. The temporal stability of left NAcc activity during anticipation of large gains is depicted in Figure 3 (bivariate r = 0.69; 90% bootstrapped confidence intervals (1000 iterations) = 0.51–0.85), and the temporal stability of right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses is depicted in Figure 4 (bivariate r = 0.50; 90% bootstrapped confidence intervals (1000 iterations) = 0.03–0.86). Right MPFC activity also showed moderate test-retest reliability during anticipation of large gains (+$5.00 ICC = 0.47/0.64, p < 0.05), as well as during anticipation of nonloss (−$0.00 ICC = 0.47/0.64, p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Test-retest reliability of neural activity (n=14; single / average intraclass correlation)

| L NAcc | R NAcc | L Ant Insula | R Ant Insula | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Signal Change | ||||

| +$5.00 | 0.64 / 0.78** | 0.47 / 0.64* | 0.16 / 0.28 | 0.48 / 0.64* |

| +$0.50 | −0.07 / −0.15 | 0.25 / 0.40 | 0.01 / 0.01 | 0.19 / 0.32 |

| +$0.00 | 0.31 / 0.47 | 0.47 / 0.64* | −0.03 / −0.06 | −0.20 / −0.53 |

| −$0.00 | 0.28 / 0.47 | 0.20 / 0.33 | 0.33 / 0.49 | 0.12 / 0.22 |

| −$0.50 | 0.24 / 0.39 | 0.23 / 0.37 | 0.30 / 0.47 | 0.63 / 0.77** |

| −$5.00 | 0.02 / 0.04 | −0.04 / −0.08 | 0.15 / 0.26 | 0.47 / 0.64* |

| Contrast Values | ||||

| Gain vs no gain anticipation | 0.43 / 0.60 | 0.68 / 0.81** | −0.01 / −0.03 | 0.05 /0.09 |

| Loss vs no loss anticipation | 0.17 / 0.29 | 0.27 / 0.42 | −0.16 / −0.37 | 0.24 / 0.38 |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

L = left, R = right

Bold associations are predicted.

Figure 3. Representative subjects and temporal stability of left NAcc activity during anticipation of large gains.

Individual contrast maps for gain versus nongain anticipation at Test 1 and Test 2 (top two rows; slice anterior coordinate =11, threshold p<.001 uncorrected, cluster =16 contiguous 2 mm3 voxels). Plot depicts peak percent signal change in left NAcc during anticipation of large gains (+$5.00) at Test 1 versus Test 2 (bottom).

Figure 4. Representative subjects and temporal stability of right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses.

Individual contrast maps for loss versus nonloss anticipation at Test 1 and Test 2 (top two rows; slice anterior coordinate =11, threshold p<.001 uncorrected, cluster = 16 contiguous 2 mm3 voxels). Plot depicts peak percent signal change in right anterior insula during anticipation of large losses (−$5.00) at Test 1 versus Test 2 (bottom).

By comparison, temporal stability of contrast coefficients (similar to measures more commonly reported in the literature) was lower (Table 4). The contrast of left NAcc activity (ICC = 0.43/0.60, p < 0.05) and right NAcc activity (ICC = 0.68/0.81, p < 0.01) during anticipation of all gains versus nongains showed moderate to strong test-retest reliability, but neither the contrast of right anterior insula activity (ICC = 0.24/0.38, n.s.) nor of left anterior insula activity (ICC= −0.16/−0.37, n.s.) during anticipation of all losses versus nonlosses was reliable. In these cases, the relatively lower temporal stability of contrast values versus averaged anticipatory activity by condition may have resulted from combining more reliable activity during anticipation of large incentives with less reliable neural activity during anticipation of small incentives and nonincentives. Subsequent analyses therefore focused on anticipatory activity averaged within each condition, rather than contrasts across conditions.

Validity of neural responses

Neural activity might either relate specifically to affective traits, or alternatively, to more general individual differences in perception, arousal, salience, attention, or motor preparation. To verify specific links from affective traits to stable neural responses, we correlated trait Positive Arousal with NAcc volume of interest activity during anticipation of large gains and trait Negative Arousal with anterior insula volume of interest activity during anticipation of large losses.

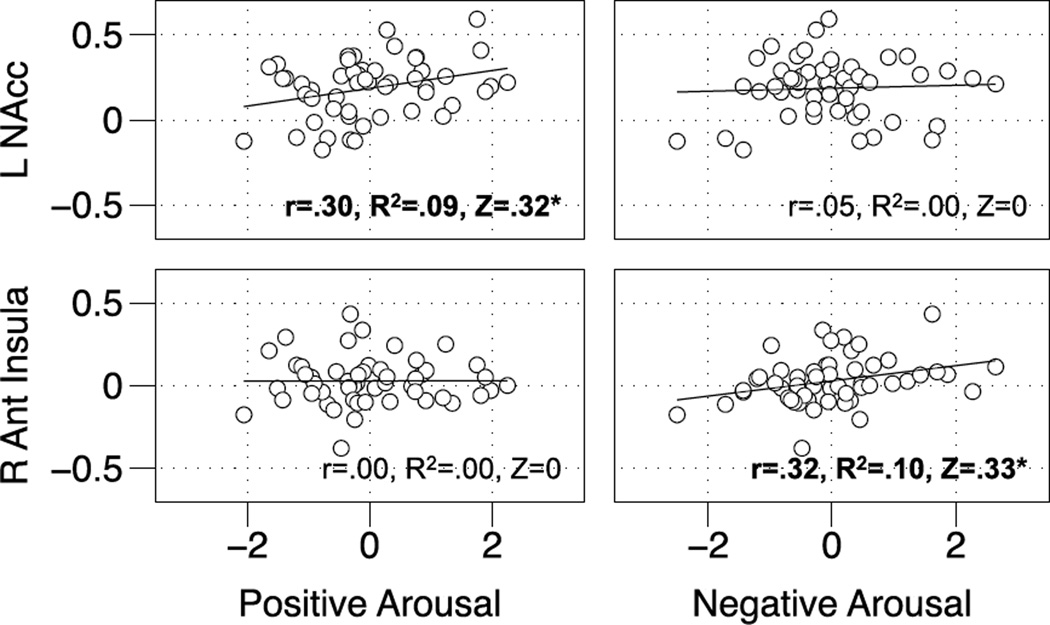

Trait Positive Arousal was significantly associated with left NAcc activity (r = 0.31, p < 0.05) but not right NAcc activity (r = 0.12, n.s.) during anticipation of +$5.00 gains. Trait Negative Arousal, however, was not associated with either left NAcc activity (r = 0.05, n.s) or right NAcc activity (r = −0.07, n.s.) during anticipation of +$5.00 gains (Figure 5; Table 5). In contrast, trait Negative Arousal was significantly associated with right anterior insula activity (r = 0.32, p < 0.05) but not left anterior insula activity (r = 0.18, p=ns) during anticipation of −$5.00 losses. Trait Positive Arousal, however, was not significantly associated with right anterior insula activity (r = 0.00, n.s.) or left anterior insula activity (r = 0.14, n.s.) during anticipation of −$5.00 losses (Figure 5; Table 5). Although reliable, MPFC activity was not significantly associated with trait Positive Arousal during anticipation of +$5.00 gains (r = 0.21, n.s.) or with trait Negative Arousal during anticipation of −$5.00 losses (r = 0.10, n.s.). Finally, left NAcc activity during anticipation of +$5.00 gains was not significantly associated with right anterior insula activity during anticipation of −$5.00 losses (r = 0.20, n.s.), establishing statistical independence of neural measures.

Figure 5. Associations of affective traits with neural activity during anticipation of large gains and losses.

Left NAcc activity during anticipation of large gains (+$5.00) was significantly associated with trait Positive Arousal (r=.30, R2 = .09, Fisher's Z=.32, p<.05; upper left) but not trait Negative Arousal (r=.05, p=ns; upper right), whereas right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses (−$5.00) was significantly associated with trait Negative Arousal (r=.32, R2 = . 10, Fisher's Z=.33, p<.05; lower left) but not trait Positive Arousal (r=.00, p=ns; lower right).

Table 5.

Valid associations of neural activity with affective traits

| L NAcc / PA | R NAcc / PA | L Ant Insula / NA | R Ant Insula / NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +$5.00 | 0.31* | 0.12 | 0.34* | 0.16 |

| +$0.50 | 0.14 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| +$0.00 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| −$0.00 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.01 |

| −$0.50 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.32* | 0.29 |

| −$5.00 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.32* |

p < 0.05, uncorrected

L = left, R = right

Bold associations are predicted.

Auxiliary analyses verified that these patterns of valid associations held in the retested subsample (n = 14). Specifically, trait Positive Arousal was significantly associated with left NAcc activity during anticipation of +$5.00 gains (r = 0.50, p < 0.05) and trait Negative Arousal was significantly associated with right anterior insula activity during anticipation of −$5.00 losses (r = 0.48, p < 0.05). These associations were also qualitatively similar at retest, although they did not reach conventional levels of significance (i.e., trait Positive Arousal was associated with left NAcc activity during anticipation of +$5.00 gains (r = 0.33) and trait Negative Arousal was associated with right anterior insula activity during anticipation of −$5.00 losses (r = 0.11).

To rule out potential individual difference confounds of age, sex, wealth, or movement, we correlated potential confounds with stable neural responses and affective traits. In the event of a significant association with stable neural responses, we conducted a regression analyses that included both the affective trait of interest and the potential confound. Only one of these individual difference variables showed a significant association with stable neural responses. Consistent with previous findings (Samanez-Larkin et al., 2007), age was associated with right anterior insula activity during anticipation of −$5.00 losses (r = −0.46, p < 0.001), but not with left NAcc activation during anticipation of +$5.00 gains (r = −0.24, n.s). All other correlations of potential confounds with stable neural responses were insignificant (including age, sex, wealth, motion, and reaction time). Further, all correlations of potential confounds with affective traits were insignificant, save an unpredicted association of Negative Arousal with sex (Table 6). Further regression analyses revealed that Positive Arousal was still significantly associated with left NAcc activity during anticipation of +$5.00 gains (t = 2.02, p < 0.05), and that Negative Arousal was still marginally associated with right anterior insula activity during anticipation of −$5.00 losses (t = 1.87, p < 0.07), even after controlling for potentially confounding effects of age (which nonetheless remained strongly associated with right anterior insula activity during anticipation of −$5.00 losses; t = −3.23, p < 0.005).

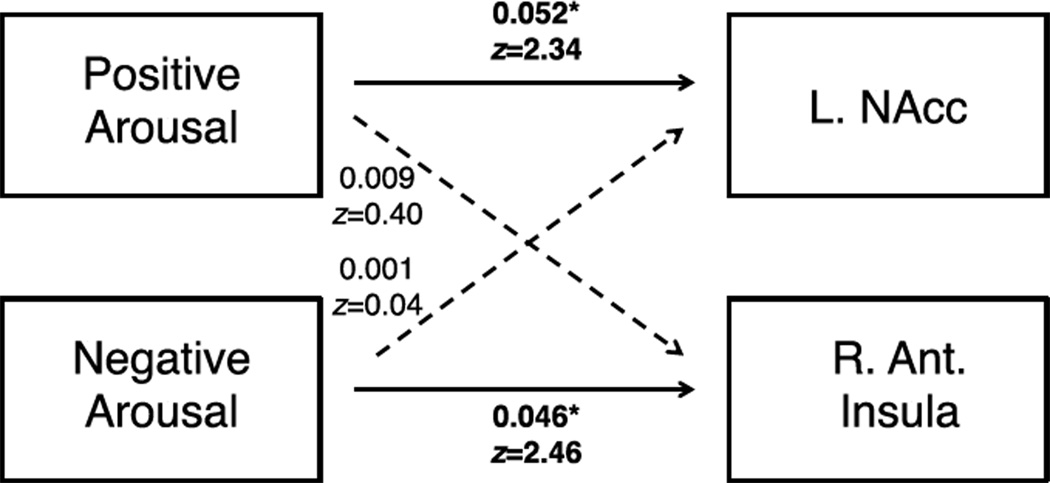

Structural equation modeling tested two models to statistically confirm a double dissociation account of the links between activity in different brain regions and distinct affective traits (e.g., Asendorpf et al., 2002). A fully connected model fit the structure of the data (χ2(4) = 2.29; p = 0.68; comparative fit index (CFI) = 1, root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0). Scrutiny of the path coefficients, however, revealed a selective pattern in which only two of the four freely varying paths were significant – those between L NAcc activity to +$5.00 cues and the Positive Arousal trait (coefficient = 0.052; standard error = 0.022; Z = 2.34; p =.02), and between right anterior insula activity to −$5.00 cues and the Negative Arousal trait (coefficient = 0.046; standard error = 0.019; Z = 2.46; p =.01). Thus, a reduced model only allowing these two paths to freely vary also fit the data (χ2(6) = 2.44, p = 0.87; CFI = 1; RMSEA = 0). Statistical comparison of the full and reduced models revealed that the full model did not fit the data better than the reduced model (χ2(2) diff = 0.15, p = .93), and further indicated that the reduced model (AIC = 198.56, BIC = 206.36) provided a more parsimonious fit to the data than the full model (AIC = 202.40, BIC = 214.11).

Association of neural trait stability and affective traits

Together, these findings suggest that the most stable neural response traits (i.e., left NAcc activity during +$5.00 gain anticipation, and right anterior insula activity during −$5.00 loss anticipation) also tend to show the strongest correlations with affective traits. However, differential associations might relate more to signal-to-noise ratio within a testing session than to test-retest reliability across testing sessions. To compare these possibilities, we correlated the magnitude of the association between neural and affective traits with neural trait stability across sessions and signal-to-noise ratio (i.e., average percent signal divided by standard deviation over the entire timecourse for each voxel) within sessions across all volumes of interest and conditions (i.e., 2 volumes of interest × 2 sides × 6 conditions = 24 cells). Results revealed a significant association of validity with test-retest reliability (r = 0.45, p < 0.05), but not with signal to noise ratio (r = −0.05, n.s.).

Discussion

By combining a task that elicits anticipation of both gains and losses (i.e., the MID task) with functional magnetic resonance imaging, we found evidence that activity in distinct neural circuits links to different affective traits. Further, only activity in reliably activated regions (i.e., at greater than two year retest) was associated with affective traits. Specifically, left NAcc activity during anticipation of large gains was associated with individual differences in trait Positive Arousal, whereas right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses was associated with individual differences in trait Negative Arousal. These associations were specific (i.e., not due to general changes in neural activity) and could not be fully accounted for by other potential individual difference confounds (including age, sex, wealth, or motion). Structural equation modeling confirmed a double dissociation interpretation of the selective associations between NAcc activity and trait Positive Arousal and anterior insula activity and trait Negative Arousal. Together, these findings suggest that individual differences in neural responses during anticipation of gain and loss may index long-suspected brain substrates of affective traits.

The observed links between affective traits and neural activity may clarify existing findings. Some studies have linked traits associated with individual differences in Positive Arousal to striatal activity (e.g., including Extraversion: Knutson and Bhanji, 2006; Behavioral Activation: Abler et al., 2006; Bjork et al., 2008, Hahn et al., 2009; Simon et al., 2010; and Impulsivity: Buckholtz et al., 2010). Other findings, however, have linked positive affective traits to different circuits, or presumably have not found the predicted associations (e.g., see reviews by Kennis et al., 2013; Smillie, 2013). Importantly, within the same task, we found that trait Positive Arousal was selectively associated with reliable NAcc activity during anticipation of large gains (and not small gains or any magnitude of losses), supporting a Positive Arousal account of NAcc activity (e.g., Knutson and Greer, 2008), and further highlighting experimental conditions conducive to eliciting these associations (e.g., specific neural regions, positive incentive valence, and large incentive magnitude).

Other studies have linked traits associated with individual differences in Negative Arousal to anterior insula activity (e.g., including Neuroticism: Canli, 2004; Drabant et al., 2011; Villafuerte et al., 2012; and Anxiety: Choi et al., 2012; Simmons et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2007; Terasawa et al, 2012). In the present study, Negative Arousal was most strongly associated with right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses (but not during anticipation of small losses or any magnitude of gains). Consistent with more variable test-retest reliability in the left anterior insula, the association of Negative Arousal with insula activity was less robust and more lateralized than was the association of Positive Arousal with NAcc activity. In addition to Negative Arousal, decreased age was also associated with increased right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses, replicating previous findings (Samanez-Larkin et al., 2007). However, inclusion of age as a potential confound could not fully account for the predicted association of Negative Arousal with right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses. By contrast, affective traits were not associated with stable activity in an MFPC control region implicated in valuation but not anticipation of incentives in the context of the MID task (Knutson and Greer, 2008).

Beyond linking affective traits to stable neural responses during incentive anticipation, the findings have significant methodological implications. First, standard measures of neural activity (e.g., contrasts or fitted functions) may suffer from reduced reliability by mixing neural responses to different task components (e.g., unreliable components with reliable components). For example, in the current data, while right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses showed significant test-retest reliability, right anterior insula activity during anticipation of nonlosses did not, and neither did their contrast (see Table 3). Since contrasts and fitted functions are often derived from percent signal change measures, they lay one additional transformational step away from underlying neural events. Thus, percent signal change may more closely link to physiology than contrasts or fitted functions (e.g., Knutson and Gibbs, 2007). Whether percent signal change or fitted functions have higher test-retest reliability or psychological validity remains an open empirical question, and the degree to which the current pattern of results extends to other probe tasks also remains to be explored. While the present findings do not invalidate the use of contrasts (as traditionally used to localize activity in the MID task), they suggest that even more robust measures might be obtained by selective averaging of peak activity. Second, auxiliary analyses implied that validity depends more on test-retest reliability across sessions than signal-to-noise ratio within a session. Although methodologists have argued for recruiting ever-increasing numbers of subjects to ensure the robustness of research findings (e.g., Ioannidis, 2005), a more parsimonious and efficient solution for expensive neuroimaging studies might involve improving measurement. Specifically, more reliable and valid “neurophenotypes” (e.g., Knutson, 2009) might more robustly link downward to physiological processes as well as upward to psychiatric symptom profiles (see also Insel et al, 2010).

The current findings also advance existing research by specifically indicating where and when neural activity should link to affective traits (e.g., Canli, 2006; Depue & Collins, 1999). This study represents a first attempt to simultaneously examine the reliability and validity of FMRI markers of personality. To maximize generalizability, a large community sample of diverse ages was assessed. To ensure that affective trait measures were independent and reduce punitive corrections for testing multiple hypotheses, “meta-factor” scores were derived from multiple psychometric measures that index trait Positive Arousal and Negative Arousal. To verify stability of neural measures, we repeatedly administered a well-established neuroimaging task (i.e., the Monetary Incentive Delay Task) at a substantial retest interval longer than two years. To control for commonly covarying factors related to perception, arousal, salience, attention, and motor preparation (e.g., Clithero et al., 2011), the Monetary Incentive Delay Task included both gain and loss frames. To establish selectivity, we further verified distinct associations of reliable neural markers with indices of trait Positive Arousal and Negative Arousal using structural equation modeling, and demonstrated that other individual difference confounds could not account for the observed associations. Together, these findings extend a critical lesson from psychometrics to neuroimaging – validity first requires reliability.

While this study offers novel strengths related to generalizability, reliability, and validity, it also has limitations. First, while subjects were selected from a community sample representative of the San Francisco Bay Area, generalization to broader populations remains to be established. Second, although the study included a relatively large sample with more than adequate power to detect group activations, effect sizes of correlations of affective traits with stable neural responses were only moderate. While observed effect sizes were similar to those observed in other studies that relate affective traits to behavior (Kenrick & Funder, 1988), adequate power for replication may require an even larger sample or more targeted measures (Yarkoni, 2009). Third, although our predictions specifically focused on the association of affective traits with anticipatory neural activity (Knutson and Greer, 2008), other dimensions of personality and aspects of neural reactivity deserve exploration. For instance, neural responses during incentive anticipation in other regions not robustly recruited in group analyses (e.g., the orbitofrontal cortex or amygdala) or that respond to other task components (e.g, outcomes) deserve exploration, as do links to other personality traits (e.g., constraint). Fourth, while the findings indicate that anticipation of larger incentives invokes more stable neural responses, they do not clarify whether this association depends on the absolute or relative magnitude of the largest incentives. The most conservative assumption for future studies is that absolute incentive magnitude plays a role -- consistent with higher reported reliability in studies that use larger (i.e., €2.00; Plichta et al., 2012) versus smaller rewards (i.e., €0.10; Fliessbach et al., 2010) -- but future studies with controlled manipulations will be necessary to fully resolve this question. Fifth, while FMRI activity is directionally related to postsynaptic energy utilization (Logothetis and Wandell, 2004), little is known about the physiological basis of the blood oxygen level dependent signal, particularly with respect to neurochemistry. While Knutson and Greer (2008) have predicted that phasic dopamine modulates NAcc FMRI activity and phasic norepinephrine additionally modulates anterior insula FMRI activity, studies using other neuroimaging techniques are necessary to triangulate on neurochemical correlates of affective traits (e.g., Buckholtz et al., 2010; Schott et al., 2008).

Beyond addressing historical theories, these findings hold practical significance for future research. Studies of individual differences in incentive processing may enhance power by targeting the most effective manipulations (e.g., anticipation of large incentives) and stable patterns of activation (e.g., onset activity in left NAcc and right anterior insula volumes of interest). Inconsistent findings in the current literature might also resolve after consideration of the temporal stability of neural responses. Stable neural responses might even inform the construction of better-aligned psychometric instruments in future samples, potentially minimizing the need for costly neural assessments. To the extent that affective traits index not only healthy individual differences, but also psychopathological symptoms in extreme cases, the findings should eventually have implications for psychiatric diagnosis and intervention (Insel et al., 2010; Krueger et al., 1996). In fact, large cross-national studies have begun to incorporate neuroimaging tasks (like the MID task) for longitudinal prediction of psychiatric outcomes (e.g., Schneider et al., 2012). Given these exciting advances, the time is ripe for finally bridging the gap between neural and psychological measures of affective traits.

Conclusions

These findings link activity in distinct neural circuits to different affective traits. On the one hand, left NAcc activity during anticipation of large gains is stable over 2.5 years and correlates with trait Positive Arousal. On the other hand, right anterior insula activity during anticipation of large losses is stable over 2.5 years and correlates with trait Negative Arousal. Together, these results highlight distinct neural markers for affective traits, and potentially for related psychiatric symptoms.

Figure 6. Structural equation model supporting a double dissociation interpretation of links from affective traits to brain activity.

This full model fits the data ((χ2(4) = 2.29; p = 0.68; Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 1, Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0), but path coefficients from trait Positive Arousal to L NAcc activity to the +$5.00 cue (Z = 2.36, p < 0.05) and from trait Negative Arousal to R Anterior Insula activity to the −$5.00 cue (Z = 2.46, p < 0.05) are significant, while crossover paths are not.

Highlights.

Left NAcc activity during gain anticipation is stable over 2.5 years.

Right anterior insula activity during loss anticipation is stable over 2.5 years.

Trait positive arousal correlates with left NAcc activity during gain anticipation.

Trait negative arousal correlates with right anterior insula activity during loss anticipation.

Findings highlight neural markers for affective traits and related psychiatric symptoms.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dennis P. Chan and Andrew J. Trujillo for assistance with subject recruitment, data acquisition, and analysis; as well as Steve W. Cole, James J. Gross, Ewart A. C. Thomas, and two anonymous reviewers for comments on previous drafts of the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institute on Aging grants R21-AG030778 and P30-AG017253, as well as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority Investor Education Foundation. CCW was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and National Institute of Mental Health grant T32-MH020006. GRSL was supported by National Institute on Aging awards F31-AG032804, F32-AG039131, and K99-AG042596.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Dedication

This work is dedicated to the memory of mentor and friend Daniel Hommer (05/08/47–01/02/13).

References

- Abler B, Walter H, Erk S, Kammerer H, Spitzer M. Prediction error as a linear function of reward probability is coded in human nucleus accumbens. Neuroimage. 2006;31(2):790–795. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW. Traits revisited. American psychologist. 1966;21(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB, Banse R, Mücke D. Double dissociation between implicit and explicit personality self-concept: the case of shy behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2002;83(2):380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CM, Miller MB. How reliable are the results from functional magnetic resonance imaging? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1191(1):133–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard TJ. Genes, environment, and personality. Science. 1994:1700–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.8209250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Knutson B, Hommer DW. Incentive- elicited striatal activation in adolescent children of alcoholics. Addiction. 2008;103(8):1308–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholtz JW, Treadway MT, Cowan RL, Woodward ND, Benning SD, Li R, Ansari MS, Baldwin RM, Schwartzman AN, Shelby ES, Smith CE, Cole D, Kessler RM, Zald DH. Mesolimbic dopamine reward system hypersensitivity in individuals with psychopathic traits. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13(4):419–421. doi: 10.1038/nn.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T. Functional brain mapping of extraversion and neuroticism: learning from individual differences in emotion processing. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(6):1105–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, editor. Biology of personality and individual differences. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB. The inheritance of personality and ability: Research methods and findings. New York: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Choi JM, Padmala S, Pessoa L. Impact of state anxiety on the interaction between threat monitoring and cognition. Neuroimage. 2012;59(2):1912–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clithero JA, Reeck C, Carter RM, Smith DV, Huettel SA. Nucleus accumbens mediates relative motivation for rewards in the absence of choice. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2011;5:87. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS. Parametric analysis of fMRI data using linear systems methods. Neuroimage. 1997;6(2):93–103. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and Biomedical research. 1996;29(3):162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22(3):491–517. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekhof EK, Kaps L, Falkai P, Gruber O. The role of the human ventral striatum and the medial orbitofrontal cortex in the representation of reward magnitude–An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies of passive reward expectancy and outcome processing. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:1252–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabant EM, Kuo JR, Ramel W, Blechert J, Edge MD, Cooper JR, Goldin PR, Hariri AR, Gross JJ. Experiential, autonomic, and neural responses during threat anticipation vary as a function of threat intensity and neuroticism. Neuroimage. 2011;55(1):401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ. Dimensions of personality. London, UK: Transaction Publishers; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- First MB. Clinical Utility: A Prerequisite for the Adoption of a Dimensional Approach in DSM. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2005;114(4):560–564. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliessbach K, Rohe T, Linder NS, Trautner P, Elger CE, Weber B. Retest reliability of reward-related BOLD signals. Neuroimage. 2010;50(3):1168–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, John OP. Personality Dimensions in Nonhuman Animals A Cross-Species Review. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1999;8(3):69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychophysiological basis of introversion-extraversion. Behavioral Research and Therapy. 1970;8:249–266. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(70)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn T, Dresler T, Ehlis AC, Plichta MM, Heinzel S, Polak T, Lesch K-P, Breuer F, Jakob PM, Fallgatter AJ. Neural response to reward anticipation is modulated by Gray's impulsivity. Neuroimage. 2009;46(4):1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Cuthbert BN, Garvey MA, Heinssen RK, Pine DS, Quinn KJ, Sanislow C, Steinberg J, Wang PS. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis JP. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS medicine. 2005;2(8):e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennis M, Rademaker AR, Geuze E. Neural correlates of personality: An integrative review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37:73–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenrick DT, Funder DC. Profiting from controversy: Lessons from the person-situation debate. American Psychologist. 1988;43(1):23. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B. Neurophenomics + targeted stimulation = neural optimization? 2009 http://www.edge.org/q2009/q09_7.html#knutson.

- Knutson B, Bhanji J. Biology of Personality Individual Difference. New York: Guilford; 2006. Neural substrates for emotional traits? The case for extraversion; pp. 116–132. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Gibbs SEB. Linking nucleus accumbens dopamine and blood oxygenation. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:813–822. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Greer SM. Anticipatory affect: neural correlates and consequences for choice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2008;363(1511):3771–3786. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Taylor J, Kaufman M, Peterson R, Glover G. Distributed neural representation of expected value. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(19):4806–4812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0642-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): A longitudinal-epidemiological study. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1998;107(2):216. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Hairston J, Schrier M, Fan J. Common and distinct networks underlying reward valence and processing stages: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35(5):1219–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK, Wandell BA. Interpreting the BOLD signal. Annual Review of Physiology. 2004;66:735–769. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.082602.092845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Rogalsky C, Simmons A, Feinstein JS, Stein MB. Increased activation in the right insula during risk-taking decision making is related to harm avoidance and neuroticism. Neuroimage. 2003;19(4):1439–1448. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov IP. Conditioned reflexes: An investigation into the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plichta MM, Schwarz AJ, Grimm O, Morgen K, Mier D, Haddad L, Gjerdes A, Sauer C, Tost H, Esslinger C, Colman P, Wilson F, Kirsch P, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Test–retest reliability of evoked BOLD signals from a cognitive–emotive fMRI test battery. NeuroImage. 2012;60(3):1746–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012:48. [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39(6):1161–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Samanez-Larkin GR, Gibbs SE, Khanna K, Nielsen L, Carstensen LL, Knutson B. Anticipation of monetary gain but not loss in healthy older adults. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10(6):787–791. doi: 10.1038/nn1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanez-Larkin GR, Kuhnen CM, Yoo DJ, Knutson B. Variability in nucleus accumbens activity mediates age-related suboptimal financial risk taking. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(4):1426–1434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4902-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Peters J, Bromberg U, Brassen S, Miedl SF, Banaschewski T, Büchel C. Risk taking and the adolescent reward system: a potential common link to substance abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):39–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott BH, Minuzzi L, Krebs RM, Elmenhorst D, Lang M, Winz OH, Seidenbecher CI, Coenen HH, Heinze H-J, Zilles K, Duzel E, Bauer A. Mesolimbic functional magnetic resonance imaging activations during reward anticipation correlate with reward-related ventral striatal dopamine release. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(52):14311–14319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2058-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86(2):420. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons AN, Stein MB, Strigo IA, Arce E, Hitchcock C, Paulus MP. Anxiety positive subjects show altered processing in the anterior insula during anticipation of negative stimuli. Human brain mapping. 2011;32(11):1836–1846. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JJ, Walther S, Fiebach CJ, Friederich HC, Stippich C, Weisbrod M, Kaiser S. Neural reward processing is modulated by approach-and avoidance-related personality traits. Neuroimage. 2010;49 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.016. 1868-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smillie LD. Extraversion and reward processing. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22:167–172. doi: 10.1177/0963721412474460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specht K, Willmes K, Shah NJ, Jäncke L. Assessment of reliability in functional imaging studies. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2003;17(4):463–471. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Simmons A, Feinstein J, Paulus M. Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):318–327. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa Y, Shibata M, Moriguchi Y, Umeda S. Anterior insular cortex mediates bodily sensibility and social anxiety. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1093/scan/nss108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villafuerte S, Heitzeg MM, Foley S, Yau WW, Majczenko K, Zubieta JK, Burmeister M. Impulsiveness and insula activation during reward anticipation are associated with genetic variants in GABRA2 in a family sample enriched for alcoholism. Molecular psychiatry. 2011;17(5):511–519. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Wiese D, Vaidya J, Tellegen A. The two general activation systems of affect: Structural findings, evolutionary considerations, and psychobiological evidence. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1999;76(5):820. [Google Scholar]

- Wundt W. Outlines of psychology. London, UK: Wilhelm Engelmann; 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Yarkoni T. Big correlations in little studies: Inflated fMRI correlations reflect low statistical power—Commentary on Vul et al. 2009. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4(3):294–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]