Abstract

Characterization of the degradation mechanisms and resulting products of biodegradable materials is critical in understanding the behavior of the material including solute transport and biological response. Previous mathematical analyses of a semi-interpenetrating network (sIPN) containing both labile gelatin and a stable cross-linked poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) network found that diffusion-based models alone were unable to explain the release kinetics of solutes from the system. In this study, degradation of the sIPN and its effect on solute release and swelling kinetics were investigated. The kinetics of the primary mode of degradation, gelatin dissolution, was dependent on temperature, preparation methods, PEGdA and gelatin concentration, and the weight ratio between the gelatin and PEG. The gelatin dissolution rate positively correlated with both matrix swelling and the release kinetics of high-molecular-weight model compound, FITC-dextran. Coupled with previous in vitro studies, the kinetics of sIPN degradation provided insights into the time-dependent changes in cellular response including adhesion and protein expression. These results provide a facile guide in material formulation to control the delivery of high-molecular-weight compounds with concomitant modulation of cellular behavior.

Keywords: Degradation, delivery vehicle, gelatin, hydrogel, poly(ethylene glycol), semi-interpenetrating polymer network (sIPN)

1. Introduction

Through interaction with the physiological environment, biomaterials undergo dynamic structural changes via multiple mechanisms leading to alterations in bulk and surface chemistry and composition [1–6]. These dynamics also affect biological interactions such as cell adhesion, activation and the host response [7, 8]. Biodegradable materials, including hydrogels, are commonly employed in wound-healing and tissue-engineering applications where non-invasive removal of the material is advantageous [9–11]. Multiple forces influence degradation including both cellular- and acellular-driven mechanisms, such as hydrolysis of the polymeric backbone, dissolution of the structural components, and enzymatic and reactive-oxygen-mediated polymer-chain scission [12]. Degradation of biomaterials has also been exploited as a method to control release of entrapped therapeutics including high-molecular-weight compounds such as proteins [13–16]. This strategy is based on the model behavior where factors that reduce the size of water-filled spaces inside the material matrix, such as solute size or polymer chain mobility, sterically hinder solute diffusion. The loss or breakdown of these structural components leads to an increase in average mesh size and thereby promotes diffusion-based transport. Alternatively, association between the degradation products and the target solute may act as a vehicle for assisted transport as the degraded components diffuse out of the material matrix. Thus, insights into the degradation process and the subsequent changes in the material structure are critical in the engineering a drug-delivery matrix.

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels have been extensively used for controlled delivery of small to large molecules, as well as therapeutic cells. Not only is PEG highly biocompatible, but it also provides a platform which can be modified. For example, previous research has explored the addition of enzyme-cleavable peptide sequences into the PEG backbone to control material degradation in a biological environment [10, 11, 17]. However, establishing a large-scale chemical synthesis methodology necessary for commercial applications can become cost-prohibitive and present regulatory challenges. We have explored an alternative method of manipulating hydrogel degradation whereby the addition of a biocompatible and commonly-used labile component to a stable network is employed to create void spaces within the matrix over time (Fig. 1). Semi-interpenetrating polymer networks (sIPN) are a class of macromolecule system that are often employed in order to take advantage of the different properties of multiple material components that may have vastly different chemical and physical characteristics [18, 19]. However, the interaction of the components may also influence the resulting properties of the sIPN such as mechanical, degradation and solute transport characteristics. Previous research exploring the use of sIPNs with a variety of compositions has demonstrated alterations in both degradation kinetics and material structure compared to hydrogels composed of a single component or two covalently crosslinked components [18, 19]. We have employed a stable poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGdA)-based network with a labile gelatin component as the basis for our sIPN fomulation. As production of pharmaceutical-grade gelatin is already overseen by the FDA, the addition of gelatin to a medical device such as a hydrogel system is not expected to result in extensive regulatory or production hurdles because of these predicates. The PEG matrix provides mechanical stability whereas the addition of gelatin has been shown to increase hydration and the Young’s modulus [20]. Previous work has demonstrated the efficacy of the sIPN as a dermal wound dressing in both rat and porcine models as compared to clinical standards. The sIPN maintained wound hydration, functioned as a barrier to external infiltration, and was capable of delivering soluble factors locally to the wound site [21–23]. Although we have extensively investigated the short- and long-term effect of this degradable material on cell-mediated interaction in vitro and in vivo [21–27] and solute release kinetics [28, 29], the dynamic behavior of the material composition needs to be elucidated in order to provide the underlying mechanisms to the results. For example, previous analyses of solute release kinetics from the sIPN found that diffusion-based mathematical models alone were unable to fully characterize solute release from this system. The addition of a labile component to the matrix requires that degradation- or dissolution-controlled mechanisms be considered as primary driving forces for solute release. Additionally, most published work on biodegradable materials contributes the observed biological functions and physical properties to the original material composition. What is not clear is what the cells and tissues react to throughout the time-course where the biodegradable material is undergoing a dynamic transformation. Therefore, characterization of both the mechanics of degradation and its influence on these functionally relevant properties will provide the necessary engineering framework for future material formulations.

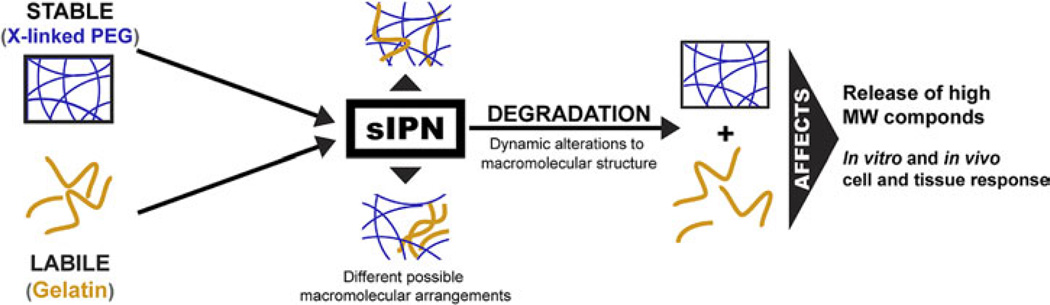

Figure 1.

A semi-interpenetrating network (sIPN) combines a stable polymer matrix with a labile component. The formulation used as well as the method of construction can influence both the structure of the matrix and the subsequent degradation kinetics. Controlling degradation through material formulation provides a relatively simply way to affect both the release of high-molecular-weight compounds and the cellular response to the material. This figure is published in colour in the online edition of this journal, which can be accessed via http://www.brill.nl/jbs

Degradation of biomaterials is typically evaluated through in vitro characterization of mass loss and subsequent changes in bulk material properties as well as chemical identification of the degradation products. The incorporation of large biomolecules into the material formulation adds additional complexity in charac-terization. For example, biomolecules such as gelatin display heterogeneity in both physical and chemical properties [30]. Thus, the degradation process resulting in changes to the macro- and micro-scale properties of the biomaterial becomes very dynamic, leading to the formation of varied degradation products over time. In this study, the impact of the sIPN composition and construction method on the rate and the molecular weight distribution of gelatin dissolution was analyzed. The underlying degradation kinetics was then compared to the hydrogel swelling and release behavior of model solutes of various molecular weights.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. sIPN and PEG Hydrogel Synthesis

sIPNs were constructed by dissolving gelatin (Type A, porcine skin, 300 bloom; Sigma-Aldrich) in ddH2O at 45–55°C. Based on bloom strength, the average molecular mass of the gelatin used is between 50 and 100 kDa (Sigma). The dissolved gelatin was then mixed with 575 Da PEGdA (Sigma-Aldrich). 2,2-Dimethoxy-2-phenyl-acetophenone (DMPA) was used as a photoinitiator at a concentration of 0.1% (w/v). Of the solution, 200 µl was then poured into 1.6-mm-thick Teflon® molds with a diameter of 9.2 mm and underwent photopolymerization under UV light with CF1000 LED (λmax = 365 nm, Clearstone Technologies) for 45 s at room temperature (RT). PEG hydrogels were constructed similarly without the addition of gelatin. Table 1 shows the nomenclature for the formulations used in this study. Formulations in Group I were chosen to examine the effect of PEGdA and gelatin concentration by using three different amounts of PEGdA while keeping either the gelatin/PEGdA ratio (2:3) or gelatin amount (130 mg/ml) constant. Formulations in Group II examined the effect the gelatin/PEGdA weight ratios (2:3, 1:1, 3:7) by simultaneously varying the gelatin and PEGdA concentrations using the same three PEGdA concentrations used in Group I. Increasing the gelatin content beyond the 1:1 weight ratio compromised the robustness of the sIPN to withstand handling, while decreasing the gelatin content beyond the 3:7 weight ratio led to bulk mechanical properties that are similar to a PEG-only hydrogel. As such, the weight ratios chosen provided a range of ratios which were mechanically stable throughout the course of the study while demonstrating properties significantly different that PEG hydrogels. Group I formulations were used for nearly all studies mentioned while Group II formulations were used only for gelatin dissolution and swelling studies.

Table 1.

Nomenclature used for the sIPN and PEG hydrogel formulations

| Group I | Group II | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label | Gelatin (mg/ml ddH2O) |

PEGdA (mg/ml ddH2O) |

Label | Gelatin (mg/ml ddH2O) |

PEGdA (mg/ml ddH2O) |

| A | 0 | 150 | J | 70 | 110 |

| B | 0 | 190 | K | 110 | 110 |

| C | 0 | 240 | L | 150 | 150 |

| D | 100 | 150 | M | 190 | 190 |

| E | 130 | 150 | N | 50 | 110 |

| F | 130 | 190 | O | 60 | 150 |

| G | 130 | 240 | P | 80 | 190 |

| H | 160 | 240 | |||

2.2. Gelatin Dissolution and Molecular Weight Analysis

sIPN were placed in individual polypropylene vials with 3 ml (V1) phosphatebuffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37°C or RT. At each time point, all media (V1) was collected and replaced with fresh media. Gelatin concentration was calculated using a BCA Total Protein Assay (Thermo Scientific) comparing samples to a gelatin standard curve (32.2–6000 µg/ml). The cumulative gelatin dissolution amount (mt ) at time t was calculated using equation (1):

| (1) |

where Cn is the concentration at time t and Ci the concentration at time ti. mt was then divided by the original mass of gelatin within the sIPN (m0) to obtain the cumulative dissolution or release fraction (mt/m0). Assuming homogeneous distribution in the unpolymerized solution, m0 was estimated using equation (2):

| (2) |

where Atotal represents the total amount of gelatin added to the sIPN solution, Vdisk the volume of sIPN solution applied to each Teflon® mold and Vtotal the total volume of unpolymerized sIPN solution.

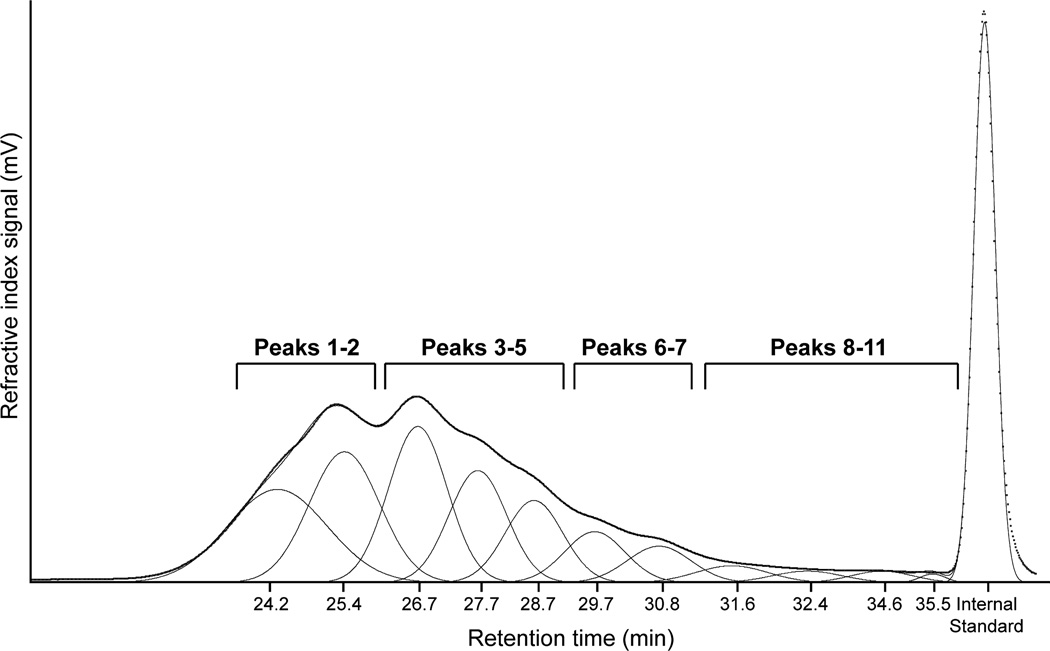

The supernatant from gelatin dissolution studies was concentrated to approx. 500 µg/ml in 0.1 M NaNO3, based on BCA results using Spin-X Concentrators (5 kDa MWCO; Corning Life Sciences). A control sample consisting of stock gelatin dissolved to 100 µg/ml in PBS and concentrated to 500 µg/ml in 0.1 M NaNO3 was used to determine the complete molecular weight distribution of gelatin. Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) was performed using a system consisting of a single phase HPLC pump (Waters 1515) with a column heater and a refractive index detector (Waters 2414). Separation was accomplished using three TSK-GEL columns (Sigma-Aldrich) in series: G5000PWXL (pore size = 1000 µm, 30 cm ×7.8 mm), G3000PWXL (pore size = 200 µm, 30 cm ×7. 8 mm), G2500PWXL (pore size < 200 µm, 30 cm ×7. 8 mm). All samples were run at 0.7 ml/min at 37°C in a mobile phase consisting of 80% (v/v) 0.1 M NaNO3/20% (v/v) acetonitrile. Chromatogram analysis was performed using PeakFit software (v4.12, SeaSolve Software) to fit 11 Gaussian peaks with center parameters that were selected based on the most prominent peaks in the chromatogram of untreated gelatin. The integral area of each peak was determined and the percent area under the curve was then calculated. For analysis purposes, peaks were grouped based on molecular weight range and overall features within the chromatogram (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the methodology used for the molecular weight distribution analysis of gelatin. Chromatograms were fit using 11 Gaussian peaks whose center parameter was selected based on the control gelatin chromatogram (shown). The integral area of each peak was determined and the percent area under the curve was then calculated. For analysis purposes, peaks were grouped based on molecular weight range and overall features within the chromatogram.

2.3. FITC-Dextran Release from sIPN and PEG Hydrogels

sIPNs or PEG hydrogel solutions were mixed with 1 mg/ml 4, 70 or 500 kDa fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled dextran (FITC-dextran, Sigma-Aldrich), photopolymerized, and placed in individual polypropylene tubes in 3 ml (V1) PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C. At each time point, 300 µl (V2) medium was removed and replaced with fresh media. Gelatin concentration was calculated as described previously. FITC-dextran concentration was quantified using Gemini XPS spectrofluorometer (ex/em: 485/520 nm; Molecular Devices). The cumulative gelatin dissolution and FITC-dextran release amount (mt ) at time t was calculated using equation (3):

| (3) |

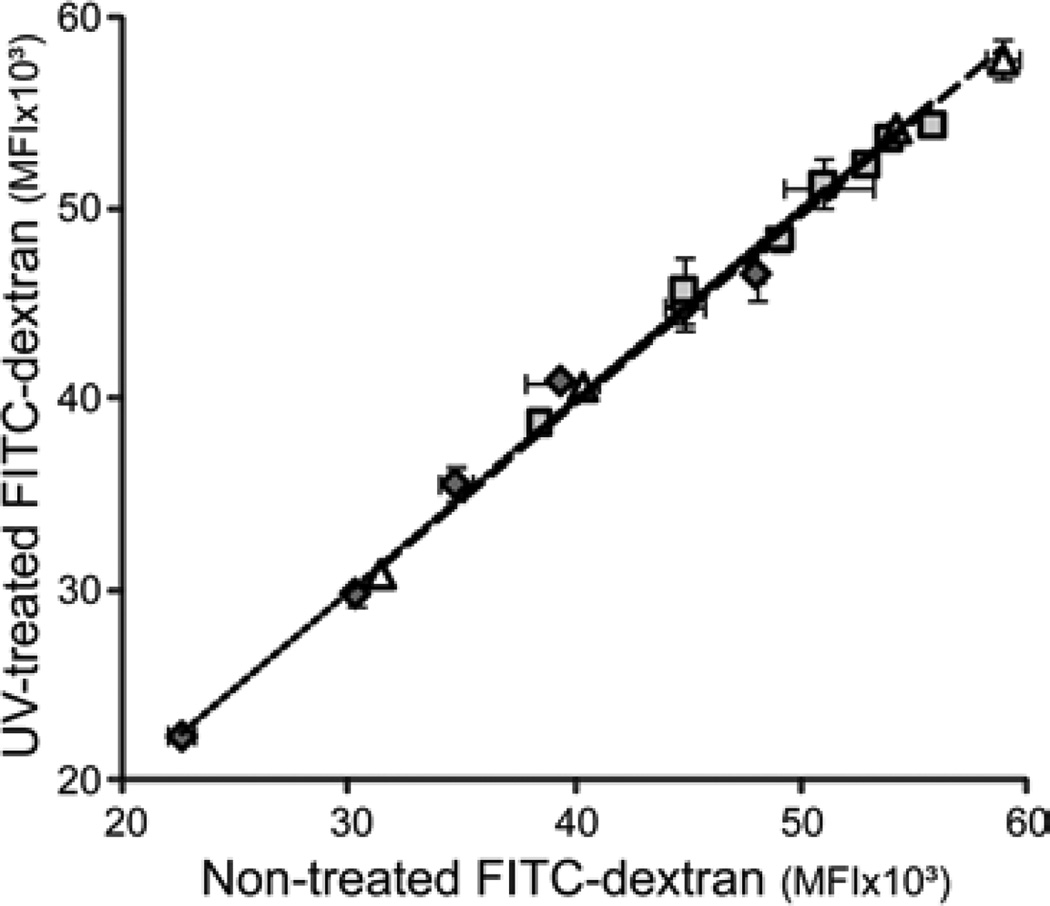

where Cn is the concentration at time t and Ci represents concentration at time ti. mt was then divided by the original mass of gelatin or FITC-dextran loaded (m0) to obtain the cumulative dissolution or release fraction (mt/m0). Assuming homogeneous distribution in the unpolymerized solution, the original mass of gelatin or FITC-dextran (m0) was estimated using equation (2). No significant change in fluorescence intensity was found in FITC-dextran samples after exposure to UV-light for 45 s, reflecting the conditions used during sIPN and PEG hydrogel photopolymerization (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of fluorescence of non-treated versus UV-exposed (λmax = 365 nm, 45 s exposure time) 4 kDa ( ), 70 kDa (

), 70 kDa ( ) and 500 kDa (

) and 500 kDa ( ) FITC-dextran (0.25–1 mg/ml in PBS). No significant change in MFI was detected between treated and non-treated FITC-dextran as shown by the slope of the linear treadline: 4 kDa (

) FITC-dextran (0.25–1 mg/ml in PBS). No significant change in MFI was detected between treated and non-treated FITC-dextran as shown by the slope of the linear treadline: 4 kDa ( , 0.99±0.01), 70 kDa (

, 0.99±0.01), 70 kDa ( , 1.00±0.01) and 500 kDa (

, 1.00±0.01) and 500 kDa ( , 1.00±0.01).

, 1.00±0.01).

2.4. Analysis of sIPN Swelling

Due to the rapid and significant weight loss caused by gelatin dissolution from the sIPN, percent swelling could not be accurately measured through the conventional mass analysis where a change in weight is used as an indicator of the addition of water to the hydrogel structure. Thus, sIPN swelling was analyzed by monitoring the change in sample area of sIPNs with an initial radius of 9.2 mm and thickness of 1.6 mm. sIPNs (n ≥ 3 for each formulation) were placed in 10 ml PBS at 37°C in a Petri dish etched with a 2×2 mm grid (Corning). At 0, 2, 4, 6, 24, 48, 77 and 168 h, photographs were taken. The area of the disc was analyzed using ImageJ software v1.32j [31] and the percent change in area from the 0 h time point was calculated.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All data are shown as mean ±SD. Gelatin dissolution, swelling and FITC-dextran release studies were conducted using n ≥ 3 for each formulation and/or construction method. Gelatin dissolution and FITC-dextran release kinetics were analyzed using unpaired Student t-test. A value of P < 0. 05 was considered statistically significant. Correlation between the rate increases and decreases of gelatin dissolution and FITC-dextran release were analyzed by using the least-squares method to cal-culate a best fit straight line. The significance of this relationship was determined by analyzing the variance using the Fisher F-statistic.

3. Results

3.1. Gelatin Dissolution from the sIPN

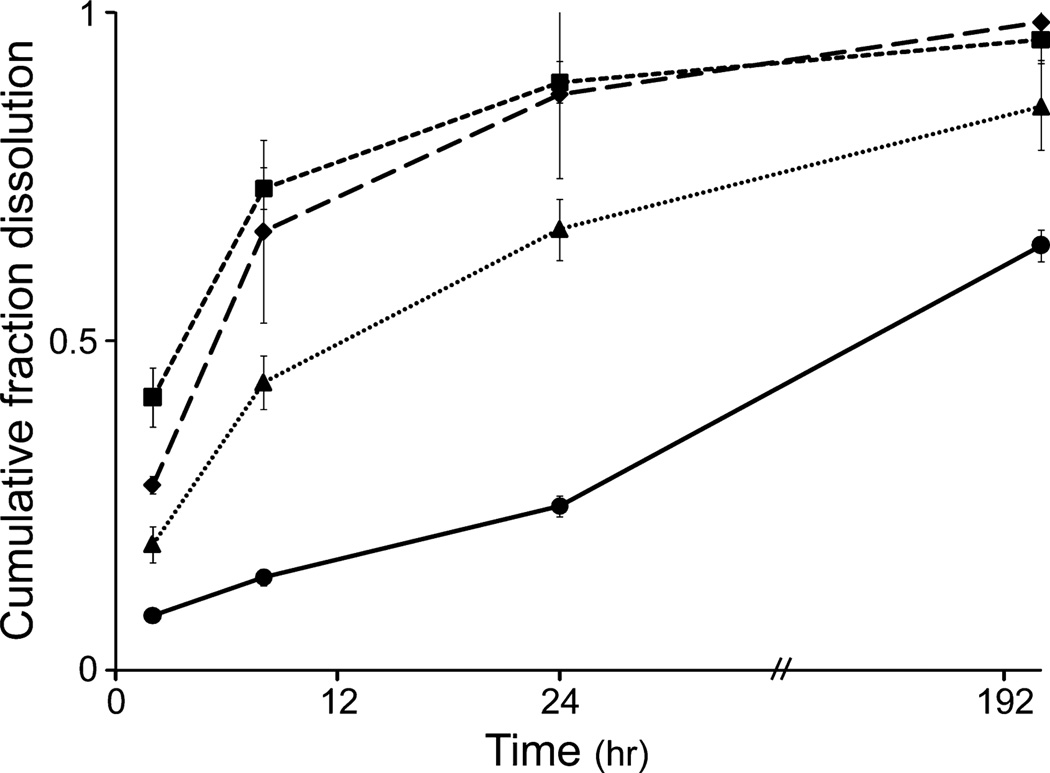

Several formulation and construction parameters were examined and included PEGdA concentration, gelatin concentration, gelatin/PEGdA weight ratio, the volume of the sIPN and the temperature of the sIPN solution at the time of photopolymerization (45 and 4°C). Additionally, dissolution was evaluated at both 37°C and RT. While differences in the rate of dissolution were seen in the initial periods (0– 8 h) when comparing amongst these factors, for all conditions and formulations most (>70%) gelatin was lost from the sIPN by 24 and 48 h at 37°C (Fig. 4). The only exception to this behavior occurred in cases where high polymer concentrations of both PEGdA and gelatin were used. In contrast, cumulative dissolution at RT did not exceed 15% for the duration of the study (168 h) for all formulations (data not shown). Decreasing the temperature of the sIPN solution at the time of photopolymerization to induce gelatin gelation also decreased the rate of dissolution during earlier time points, particularly between 4 and 6 h (Table 2). Generally, increasing the PEGdA content also led to a decrease in the rate of dissolution (Fig. 4; P < 0. 02), except in formulations containing the lowest amounts of PEGdA (D and J). To further explore the differences between formulations containing different amounts of PEGdA, the molecular weight distribution of the gelatin dissolute was characterized.

Figure 4.

Cumulative gelatin dissolution over 195 h from sIPN formulations using the same gelatin/PEGdA weight ratio (2:3): H ( ), F (

), F ( ), D (

), D ( ), J (

), J ( ). n = 3 for each formulation.

). n = 3 for each formulation.

Table 2.

Rate of gelatin dissolution (µg/h) from different formulations of sIPN where the temperature of the sIPN solution at the time of UV-polymerization was varied

| Formulation | T (°C) | Time period (h) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2 | 2–4 | 4–6 | 6–24 | 24–48 | 48–72 | 72–96 | ||

| J | 45 | 743.8 ± 54.5 | 829.9 ± 65.5 | 492.1 ± 71.3a | 96.2 ± 9.8 | 31.7 ± 1.1a | 13.0 ± 1.2a | 4.7 ± 0.3a |

| 4 | 558.2 ± 211.3 | 519.6 ± 230.1 | 283.3 ± 33.1 | 95.5 ± 17.9 | 40.4 ± 2.8 | 28.8 ± 4.8 | 15.5 ± 3.1 | |

| D | 45 | 665.9 ± 75.1 | 1020.4 ± 147.1a | 544.9 ± 123.2a | 123.5 ± 11.3 | 46.9 ± 11.7a | 17.4 ± 2.7a | 8.7 ± 1.3a |

| 4 | 386.2 ± 223.7 | 477.7 ± 154.9 | 277.2 ± 76.5 | 117.6 ± 13.8 | 71.2 ± 8.4 | 46.5 ± 7.5 | 26.5 ± 7.2 | |

| F | 45 | 675.7 ± 157.2 | 991.5 ± 70.8 | 591.9 ± 96.5a | 122.3 ± 5.7 | 53.5 ± 7.4a | 18.1 ± 1.4a | 5.8 ± 0.9a |

| 4 | 492.2 ± 154.8 | 744.6 ± 181.6 | 372.2 ± 48.0 | 120.5 ± 22.8 | 82.0 ± 11.3 | 39.6 ± 12.2 | 18.4 ± 5.0 | |

Significantly different from the same formulation of sIPN polymerized at 4°C,P < 0.05.

3.2. Molecular Weight Characterization of Gelatin Dissolution

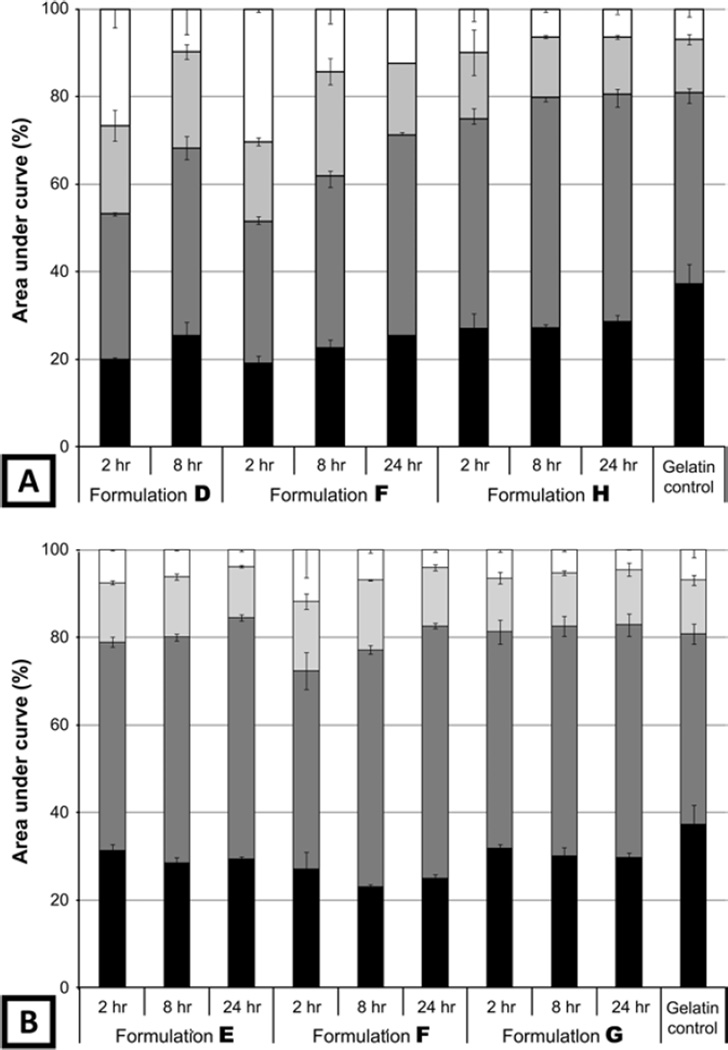

Characterization of the molecular weight of the gelatin eluting out of the sIPN over time provides an insight into both the degradation products, as well as the changes to the structure of the biomaterial over time. When the gelatin/PEGdA ratio was maintained, the molecular weight distribution of the gelatin dissolute demonstrated a bias towards lower-molecular-weight species between 0 and 8 h, except in the case of formulation H which contained the highest concentration of gelatin and PEGdA (Fig. 5A). At the highest PEGdA concentration, no bias was observed and the resulting distribution was similar to that of the gelatin control. When the gelatin concentration was kept constant and the PEGdA concentration varied, a higher percentage of lower-molecular-weight species was still seen at early time points with formulations containing lower concentrations of PEGdA; however, the bias was not as prominent as seen when the gelatin concentration was also varied (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Molecular weight distribution of gelatin disssoluted out of different formulations of sIPN between 0–2, 2–8 and 8–24 h. Peak 1 represents the highest molecular weight species while peak 11 represents the lowest molecular weight species. For analysis purposes, peaks were grouped based on molecular weight and overall features in the chromatogram: peaks 1 and 2 ( ), peaks 3–5 (

), peaks 3–5 ( ), peaks 6 and 7 (

), peaks 6 and 7 ( ) and peaks 8–11 (

) and peaks 8–11 ( ) as identified in Fig. 1. The control gelatin consists of stock gelatin which was first dissolved in the release media and then concentrated in a manner similar to the gelatin dissolution samples. (A) Formulations where PEGdA and gelatin concentrations were varied and the gelatin/PEGdA weight ratio was kept constant (2:3). (B) Formulations where the PEGdA concentration varied and the gelatin amount was kept constant (130 mg/ml).

) as identified in Fig. 1. The control gelatin consists of stock gelatin which was first dissolved in the release media and then concentrated in a manner similar to the gelatin dissolution samples. (A) Formulations where PEGdA and gelatin concentrations were varied and the gelatin/PEGdA weight ratio was kept constant (2:3). (B) Formulations where the PEGdA concentration varied and the gelatin amount was kept constant (130 mg/ml).

3.3. Swelling of sIPN

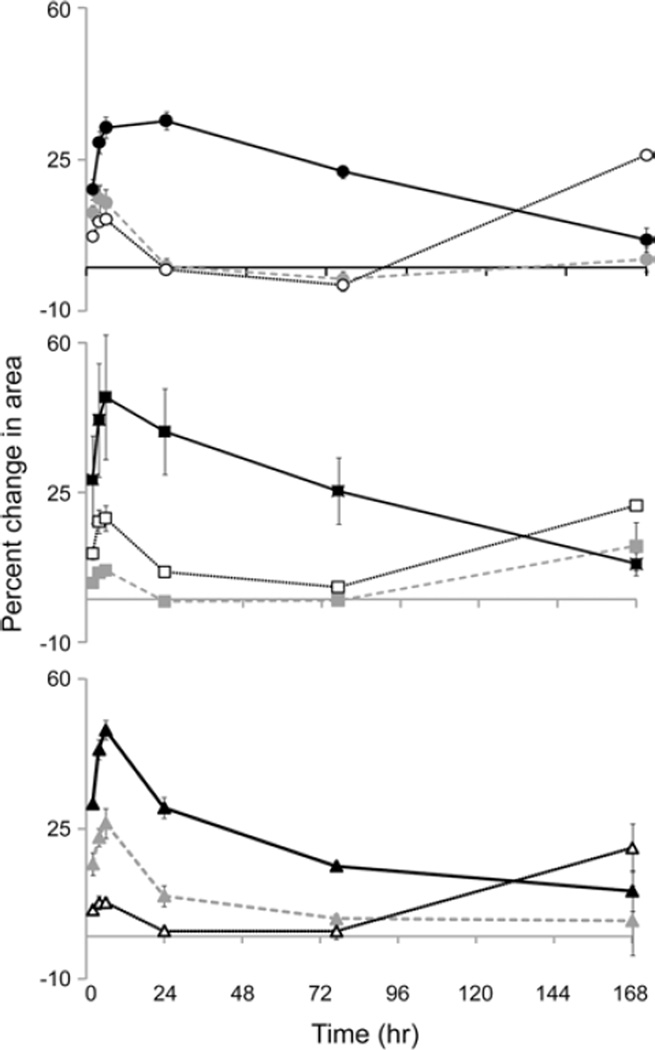

In general, swelling of the sIPN within the first 168 h consisted of three phases: an initial rapid increase in size followed by decrease in size and then a second period of hydrogel swelling. The length of time that each phase lasted and the extent of change in hydrogel size demonstrated dependence on both the amount of gelatin and the ratio of gelatin/PEGdA (Fig. 6). When the PEGdA concentration was constant, increasing the amount of gelatin led to greater increase in size during the initial phase of swelling (P < 0. 05). When both the PEGdA and gelatin amount was changed and the weight ratio was maintained, swelling was not simply dependent on the concentration of the hydrogel components. sIPN formulations containing a gelatin/PEGdA weight ratio of 2:3 and 3:7 demonstrated the greatest degree of initial swelling in formulations containing the highest concentration of gelatin and PEGdA (P < 0. 05); however, this trend was not maintained with the two formulations with lower polymer concentrations. Formulations containing a 1:1 weight ratio of gelatin and PEGdA, on the other hand, demonstrated similar swelling kinetics at all different overall polymer concentrations.

Figure 6.

Swelling of different sIPN formulations as determined by the change in disc area over time: N ( ), J (

), J ( ), K (

), K ( ), O (

), O ( ), D (

), D ( ), L (

), L ( ), P (

), P ( ), F (

), F ( ) and M (

) and M ( ). The gelatin/PEGdA ratio (3:7(

). The gelatin/PEGdA ratio (3:7( ), 2:3 (

), 2:3 ( ), 1:1(

), 1:1( )) and amount of PEGdA (110 mg/ml (

)) and amount of PEGdA (110 mg/ml ( ), 150 mg/ml (□), 190 mg/ml (

), 150 mg/ml (□), 190 mg/ml ( )) were varied. n = 3 for each formulation.

)) were varied. n = 3 for each formulation.

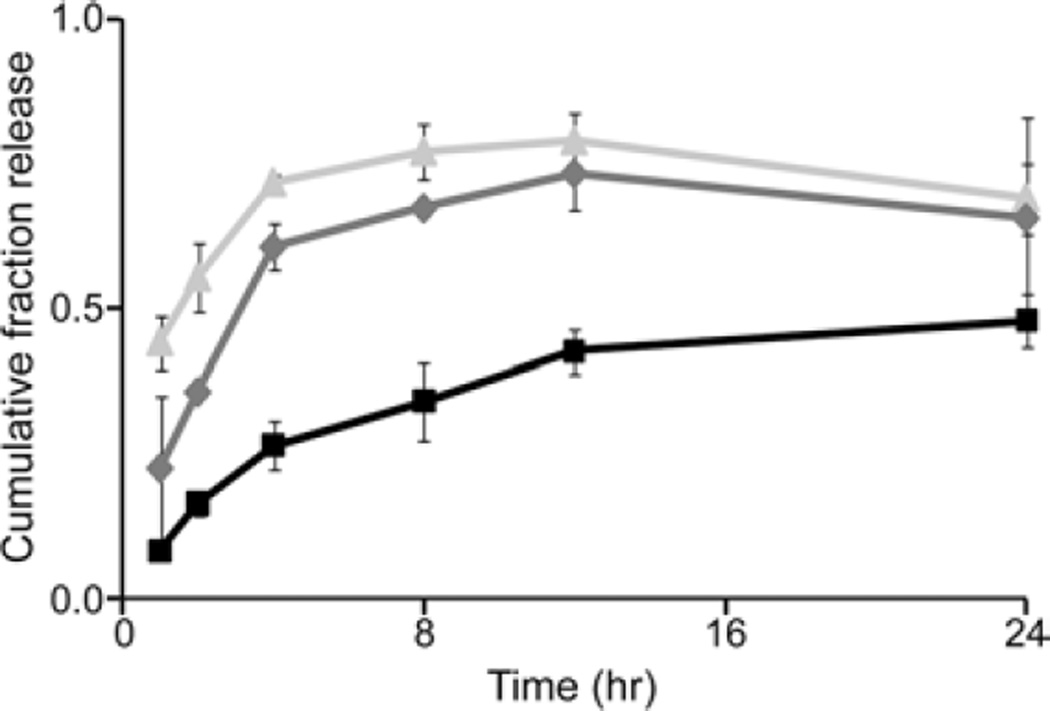

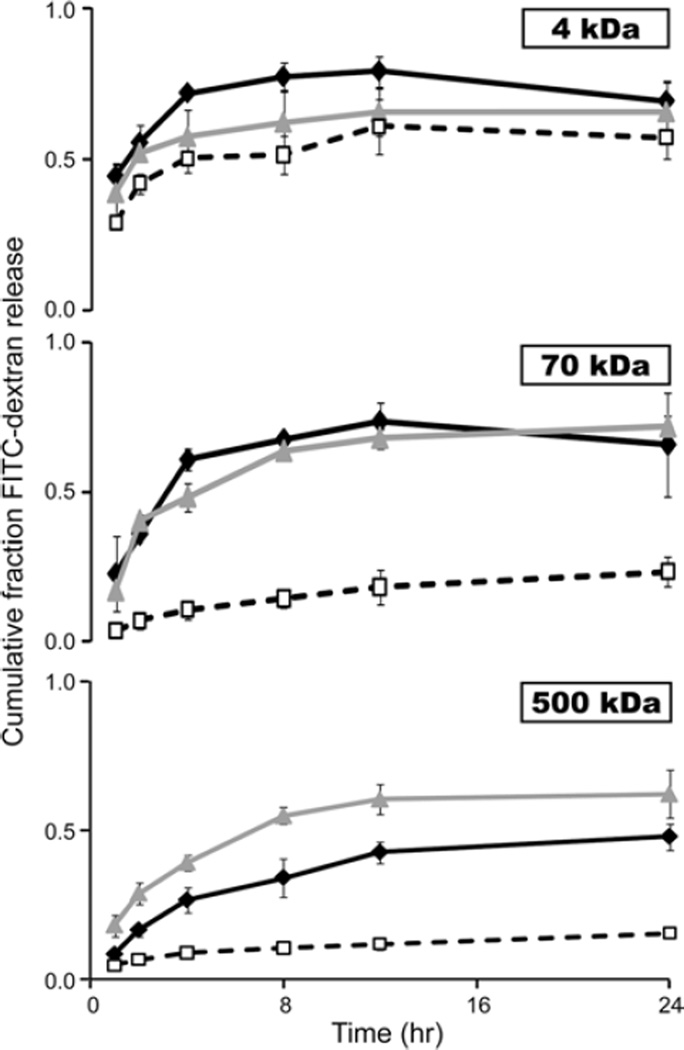

3.4. FITC-Dextran Release from sIPN and PEG Hydrogels

FITC-dextrans with a molecular mass of 4, 70 and 500 kDa were selected as model solutes to represent molecules of lower, equal and greater size than gelatin, respectively. Differences in the release kinetics of FITC-dextran were seen depending on the sIPN and PEG hydrogel formulation. In particular, PEG hydrogels demonstrated a consistent inverse relationship between molecular mass and release rate except in the case of formulation C where the release kinetics of 70 and 500 kDa FITC-dextran were similar. sIPN formulations H and G which contain the same amount of PEGdA as formulation C also demonstrated similar differences in release kinetics based on FITC-dextran molecular mass (Fig. 7;P < 0. 04 from 2–8 h between all molecular masses). sIPN formulations containing a lower concentration of PEGdA (D and E), however, only exhibited slightly increased rates of release of 4 kDa FITC-dextran compared to the higher-molecular-weight molecules. Overall, the addition of a labile gelatin component to the stable PEG hydrogel structure increased the release rate of FITC-dextran, regardless of molecular weight between 0 and 24 h (Fig. 8; p <0. 1 for 70 and 500 kDa). One exception to this trend existed where the release of 4 kDa FITC-dextran from hydrogels containing the lowest concentration of PEGdA (D and E) did not change significantly upon the addition of different amounts of gelatin. Varying the amount of gelatin caused a significant difference of the release kinetics of 500 kDa from sIPNs containing the highest amount of PEGdA (G and H;P < 0.05). In these cases, increasing the amount of gelatin decreased the rate of release (Fig. 8). The correlation between gelatin dissolution and FITC-dextran release was analyzed by comparing the changes in rate of dissolution and release over the first 24 h. Simultaneous increases or decreases in rate were considered indicative of a positive correlation. Table 3 lists the results of linear re-gression analyses of the rate changes from each formulation where the significance was determined through the Fisher F-distribution analysis of the variance.

Figure 7.

Cumulative fraction release of 4 kDa ( ), 70 kDa (

), 70 kDa ( ) and 500 kDa (

) and 500 kDa ( ) FITC-dextran loaded at 1 mg/ml in H sIPN.

) FITC-dextran loaded at 1 mg/ml in H sIPN.

Figure 8.

Cumulative fraction release of 4, 70 and 500 kDa FITC-dextran from G ( ), H (

), H ( ) and C (

) and C ( ) hydrogels.

) hydrogels.

Table 3.

Significance of correlation between changes in the rate of gelatin dissolution and FITC-dextran release between 0 and 24 h

| Formulation | 4 kDa FITC-dextran | 70 kDa FITC-dextran | 500 kDa FITC-dextran |

|---|---|---|---|

| D | NC | NC | P < 0.01 |

| E | NC | NC | P < 0.01 |

| F | P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 |

| G | P < 0.02 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 |

| H | NC | P < 0.01 | P < 0.02 |

NC, no significant correlation.

4. Discussion

Previous mathematical analyses of solute release kinetics from sIPNs using different model solutes of various molecular weights revealed that increasing the gelatin weight percentage led to an increased cumulative fractional release which contradicted classic polymer volume theory [28]. Accordingly, diffusion-based mathematical models alone were unable to explain the release kinetics of solutes from the sIPNs with varying gelatin weight percentage. Our work and other research related to degradable biomaterials have found that the addition of a non-crosslinked polymer component to the hydrogel matrix requires that degradation-or dissolution-controlled mechanisms be considered as primary driving forces for solute release. Therefore, in this study we examined gelatin dissolution and how it influenced material degradation and solute release kinetics. A summary of the major trends observed for the kinetics of gelatin dissolution and the release of the model solute, FITC-dextran, is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of overall gelatin dissolution and FITC-dextran release trends observed when hydrogel formulation is varied

| Rate of gelatin dissolution |

MW distribution of gelatin dissolute |

Release rate of FITC-dextran | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 kDa | 70 kDa | 500 kDa | |||

| Presence of gelatin | N/A | N/A | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| Increasing gelatin content | = | N/A | = | = | ↓ |

| Increasing PEGdA content | ↓ | ↑ | = | ↓ | ↓ |

| Increasing PEGdA and gelatin content | ↓ | ↑ | = | = | ↓↓ |

N/A, not applicable or not tested; =, no change observed; ↑, increase observed; ↑↑, large increase observed; ↓, decrease observed; ↓↓, large decrease observed.

The in vitro degradation of the sIPN was driven by rapid (<48 h) gelatin dissolution that was dependent on both formulation and preparation methods. Swelling of the sIPN consisted of three phases which followed similar kinetics as seen with gelatin dissolution. The initial (< 6 h) rapid increase in size was influenced by the gelatin content where higher amounts of gelatin led to a greater degree of swelling. The subsequent decrease in sIPN size corresponded to the time scale of gelatin dissolution from the hydrogel and was followed by a second period of swelling which may be attributed to PEG chain relaxation alone. Adding gelatin to the sIPN structure also significantly increased the rate of release of higher-molecular-weight FITC-dextran. Positive correlation was found between the rates of dissolution and release; however, it was not significant across all formulations and molecular weights of FITC-dextran (Table 3). As such, possible association between gelatin and FITC-dextran does not fully explain the influence of gelatin on FITC-dextran release. Several trends seen with both gelatin dissolution and FITC-dextran release demonstrated kinetics which could be attributed to steric effects of the PEG hydrogel on the labile molecules within the network. For example, increasing the concentration of PEGdA (i.e., increasing the concentration of the stable network within the sIPN) resulted in an overall decreased rate of gelatin dissolution out of the sIPN. Additionally, at early time points prior to complete PEG chain relaxation, lower-molecular-weight species of gelatin tended to diffuse out of the sIPN matrix at a greater fraction than higher-molecular-weight species. This trend was also reflected in the increased rate of release of smaller-molecular-weight FITC-dextran during this same time period. Therefore, the positive correlation seen between the rates of gelatin dissolution and FITC-dextran release could be a result of similar mechanisms related to simple diffusion. However, the lack of a bias towards dissolution of smaller-molecular-weight gelatin species with the H sIPN formulation, the decrease in the significance of the relationship between the rates of gelatin dissolution and FITC-dextran release at the highest PEG concentration, and the lack of a direct relationship between swelling and gelatin concentration, suggests the influence of other structural factors on degradation mechanics.

One possible additional factor influencing diffusion within the matrix is the formation of higher order gelatin structures. At temperatures below 30°C and concentrations above approx. 0.5%, gelatin will form gels through transition from a random coil to triple helical structure of a fraction of the gelatin fragments [30]. Dissolution of these triple helical structures will require additional energy to overcome the hydrogen bonding and, thus, the initial rate of dissolution would be reduced. This theory may account for the reduction in dissolution rate seen in sIPNs which were allowed to cool to 4°C prior to photopolymerization of the PEGdA. The favorable association of gelatin strands, as opposed to gelatin–PEG association, may also introduce areas of macromolecular phase separation between PEG and gelatin within the sIPN. Additionally, increased crowding of gelatin by PEG molecules may drive association of the gelatin molecules as has been described by excluded volume and depletion force theories [32]. Therefore, increased concentrations of both gelatin and/or PEGdA may lead to greater levels of phase separation due to enhanced gelation. As the gelatin dissolves, larger areas of free volume would then be introduced which would cause a decrease in transport barriers. Qualitatively, we observed increased opacity of the sIPN compared to PEG hydrogel, which may also be indicative of phase separation occurring between PEG and gelatin.

In addition to influencing the release kinetics of soluble molecules, the degradation of a biomaterial can alter the cellular response over time. Our previous in vitro studies showed significant differences in the cell behavior before and after the point in which we found that a majority of the gelatin has been dissoluted from the sIPN matrix. Significant differences were observed before and after 24 h of cultures in terms of cell adhesion and the release of several cytokines, growth factors and proteases [24–26]. These variations were most pronounced for sIPN and less so on non-degradable materials. For example, concurrent to a decrease in monocyte adhesion to the sIPN surface from 2 to 24 h, increases in interleukin-1α, interleukin-1β, monocyte inflammatory protein-1β, transforming growth factor-α, vascular endothelial growth factor, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor release were seen which were not reflected with monocytes adhered to a stable polycarbonate surface [26]. While a detailed study has not been performed to determine whether the cells are responding to mechanical or biochemical stimulation caused by the changes in the material structure, the kinetics of sIPN degradation seem to be an important driving force behind the time-dependent changes in cellular response. Additionally, upon introduction to a complex physiological milieu, the changes in osmotic environment and the presence of cellular-based degradation mechanisms such as extracellular reactive oxygen intermediates and enzymes are also likely to impact sIPN degradation in vivo.

5. Conclusion

Degradation of a material construct consisting of a stable PEG network and labile gelatin was characterized to provide insight into previously observed cellular response to the sIPN and solute release kinetics which could not be characterized by diffusion-based mathematical models alone. Gelatin dissolution was found to be rapid and influenced by the amount of PEG and gelatin present. The loss of gelatin was found to be a main driving force for the release of high-molecularweight soluble molecules and may be a key influential factor in determining the in vitro cellular response to this material. These results provide facile guidelines in material formulation to control the delivery of high-molecular-weight compounds with concomitant modulation of cellular behavior.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Yao Fu and Nick Ladwig for their assistance with the gelatin dissolution study. This work was supported in part by NIH Grant R01 EB6613 and NIH 5R21NS063200-02.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sublicensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

References

- 1.Lee KH, Chu CC. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999;49:25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200001)49:1<25::aid-jbm4>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto K, Kobayashi K, Endo K, Miyasaka T, Mochizuki S, Kohori F, Sakai K. J. Artif. Organs. 2005;8:257. doi: 10.1007/s10047-005-0315-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mabilleau G, Moreau MF, Filmon R, Basle MF, Chappard D. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5155. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soltes L, Mendichi R, Kogan G, Schiller J, Stankovska M, Arnhold J. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:659. doi: 10.1021/bm050867v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McBane JE, Santerre JP, Labow RS. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2007;82:984. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bat E, van Kooten TG, Feijen J, Grijpma DW. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3652. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer AJ, Clark RA. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:738. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang WW, Su SH, Eberhart RC, Tang L. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2007;82:492. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slaughter BV, Khurshid SS, Fisher OZ, Khademhosseini A, Peppas NA. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:3307. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutolf MP, Lauer-Fields JL, Schmoekel HG, Metters AT, Weber FE, Fields GB, Hubbell JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:5413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737381100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benton JA, Fairbanks BD, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6593. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann D, Entrialgo-Castano M, Kratz K, Lendlein A. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:3237. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Szleifer I, Peppas NA. Macromolecules. 2002;35:1373. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lao LL, Venkatraman SS, Peppas NA. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008;70:796. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu Y, Kao WJ. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2010;7:429. doi: 10.1517/17425241003602259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu S, Anseth KS. Macromolecules. 2000;33:2509. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aimetti AA, Machen AJ, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6048. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suri S, Schmidt CE. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:2385. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoo MK, Kweon HY, Lee KG, Lee HC, Cho CS. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2004;34:263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burmania JA, Martinez-Diaz GJ, Kao WJ. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2003;67:224. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldeck H, Chung AS, Kao WJ. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2007;82:861. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinbeck KR, Faucher L, Kao WJ. J. Burn Care Res. 2009;30:37. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181921f98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faucher LD, Kleinbeck KR, Kao WJ. J. Burn Care Res. 2010;31:137. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181cb8f27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waldeck H, Kao WJ. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:117. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung AS, Waldeck H, Schmidt DR, Kao WJ. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2009;91:742. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung AS, Kao WJ. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2009;89:841. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang XT, Waldeck H, Kao WJ. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2542. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu Y, Kao WJ. Pharm. Res. 2009;26:2115. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9923-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleinbeck KR, Bader RA, Kao WJ. J. Burn Care Res. 2009;30:98. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181921ed9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Djabourov M. Contemp. Phys. 1988;29:273. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasband WS. ImageJ. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2008. Available online at: http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman SB. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biochem. 1993;22:27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.22.060193.000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]