Abstract

In the absence of evidence‐based guidelines for high blood pressure screening in asymptomatic youth, a reasonable strategy is to screen those who are at high risk. The present study aimed to identify optimal body mass index (BMI) thresholds as a marker for high‐risk youth to predict hypertension prevalence. In a cross‐sectional study, youth aged 6 to 17 years (n=237,248) enrolled in an integrated prepaid health plan in 2007 to 2009 were classified according to their BMI and hypertension status. In moderately and extremely obese youth, the prevalence of hypertension was 3.8% and 9.2%, respectively, compared with 0.9% in normal weight youth. The adjusted prevalence ratios (95% confidence intervals) of hypertension for normal weight, overweight, moderate obesity, and extreme obesity were 1.00 (Reference), 2.27 (2.08–2.47), 4.43 (4.10–4.79), and 10.76 (9.99–11.59), respectively. The prevalence of hypertension was best predicted by a BMI‐for‐age ≥94th percentile. These results suggest that all obese youth should be screened for hypertension.

Between 1% and 5% of youth have hypertension.1, 2 Hypertension early in life can predict adult hypertension, a condition that is associated with shorter life span due to higher cardiovascular mortality.3, 4 Structural cardiac changes and organ damage due to hypertension can begin at very young ages. A recent study suggested that changes in cardiac structure caused by hypertension can be detected in children as young as 24 months.5 It is speculated that obesity may be the strongest modifiable risk factor for hypertension during childhood,6, 7 but prior to developing interventions to modify high blood pressure (BP), the magnitude of the association must be determined.

Hypertension in youth is associated with obesity.1 Some racial/ethnic minorities have a high prevalence of obesity, with a shift in the body weight distribution toward extreme obesity.8 Insights into the interplay of obesity, race/ethnicity, sex, and the occurrence of hypertension may provide support for decisions related to screening high‐risk groups for high BP and eventual effective, targeted interventions to prevent premature cardiovascular disease.

Because studies are lacking in assessing whether screening for high BP in youth reduces adverse health outcomes or delays the onset of hypertension, the evidence is currently insufficient to make recommendations for or against routine screening for high BP in asymptomatic children and adolescents.9 Because the prevalence of hypertension in normal weight is low, the question arises whether body mass index (BMI)‐for‐age can be used to identify youth at highest risk for hypertension. This information can be used to target a high‐risk population for BP screening until current evidence gaps are filled.

Using information in the electronic health records (EHRs) of a population‐based, multiethnic cohort of insured youth in Southern California, we estimated the magnitude of the association between high BP and body weight categories in children and adolescents. We also determined BMI‐for‐age thresholds that best predict pediatric prehypertension and hypertension to guide future recommendations for a targeted screening program to identify high BP in youth.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Patients

Patients enrolled in this study were pediatric members of a pre‐paid integrated health plan between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2009. Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) is the largest health care provider in Southern California. In 2012, KPSC provided health care services to more than 3.6 million members, approximately 22% of whom were 17 or younger.10 Detailed demographic characteristics of the KPSC membership population are described elsewhere.10 Members receive care in medical offices and hospitals managed by KPSC. A comprehensive EHR system, HealthConnect, was implemented region‐wide prior to 2007. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of KPSC.

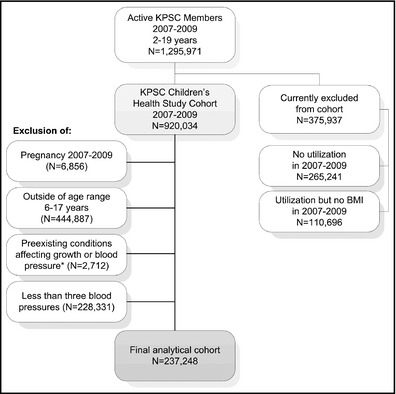

For this cross‐sectional study, we used EHR data from a subset of patients enrolled in a large population‐based cohort, the KPSC Children's Health Study, from January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2009.11 The date of the first available BP was considered the day of study enrollment. As shown in Figure 1, we excluded those who were younger than 6 years or older than 17 years (n=444,887) and patients who became pregnant anytime during the 36‐month study period (n=6856). We also excluded patients with ≥1 pre‐existing diagnoses of chronic conditions known to significantly affect growth or BP (n=2712), such as growth hormone deficiency (International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision [ICD‐9] 253.3) or overproduction (ICD‐9 253.0), aortic coarctation (ICD‐9 747.10), chronic renal disease (ICD‐9 585.x), congenital adrenal hyperplasia (ICD‐9 255.2), Cushing syndrome (ICD‐9 255.0), hyperaldosteronism (ICD‐9 255.1), and/or hyperthyroidism (ICD‐9 242). Youth who had filled a prescription for an antihypertensive medication and who had at least one outpatient diagnosis of hypertension (ICD‐9 401, 402, 403, or 404) (n=984) prior to study enrollment were identified as having hypertension. Among the remaining youth, BP measurements at 3 separate visits were required for the identification of hypertension.12 We therefore excluded participants of the KPSC Children's Health Study with fewer than 3 BP measurements within 36 months following the day of study enrollment (n=228,331), allowing annual health care visits. This resulted in a final analytical cohort of 237,248 children and adolescents aged 6 to 17 years.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) Children's Health Study and further inclusions for the final analytical cohort in the present study. *Existing diagnoses of chronic conditions significantly affecting growth or blood pressure (n=2712), such as growth hormone deficiency (International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision [ICD‐9] 253.3) or overproduction (ICD‐9 253.0), aortic coarctation (ICD‐9 747.10), chronic renal disease (ICD‐9 585.x), congenital adrenal hyperplasia (ICD‐9 255.2), Cushing syndrome (ICD‐9 255.0), hyperaldosteronism (ICD‐9 255.1), and/or hyperthyroidism (ICD‐9 242). BMI indicates body mass index.

BP Measurements and Classification

BP was measured routinely at the beginning of almost every outpatient clinical visit. Nurses and medical assistants were trained according to guidelines of the American Association of Critical Care Nurses for pediatric care.13 Digital devices (Welch Allyn Connex series, Welch Allyn Inc, Skaneateles Falls, NY) are the preferred BP measurement devices at KPSC. In some cases, a wall‐mounted aneroid sphygmometer (Welch Allyn Inc) was used. The cuff size was estimated after inspection of the bare upper arm at the midpoint between the shoulder and elbow using a bladder width approximately 40% of the arm circumference. Staff were trained to ensure that the bladder inside the cuff encircle 80% to 100% of the circumference of the arm according to standard recommendations.13 A full range of different cuff sizes were available at the locations where vital signs, including BP, are recorded in the clinics. After at least 3 to 5 minutes of rest, children were measured in a seated position with the midpoint of the arm supported at heart level. The brachial artery was palpated and the cuff was placed to ensure that that midline of the bladder was over the arterial pulsation and then the cuff was snugly wrapped and secured around the child's bare upper arm. In pediatric clinics, nurses and medical assistants are instructed to repeat the measurement if there is an elevated BP. If the level remains elevated on the repeated BP measurement, the primary care provider will measure BP using an auscultatory device in the examination room. However, repeated BP measurements are not systematically recorded in the EHR and aneroid readings cannot be distinguished from oscillometric readings in the EHR. All personnel measuring BP is certified in BP measurement during their initial staff orientation and recertified annually. In pediatrics and family practice, staff must complete a Web‐based training session and successfully pass a certification process that includes knowledge of preparing patients for measuring BP, selecting correct cuff size, and using standard techniques for BP measurement. In addition to the Web‐based training, staff is observed measuring BP to verify their competency. However, the intensity of this training may vary by medical center and deviations of the preferred measurement method may have occurred.

BP measures for all outpatient encounters were extracted from the EHR from the date of enrollment until 36 months after this date unless the measured body temperature at the time of the encounter was >100.4°F or >38.0°C. In clinical settings, follow‐up visits may not be scheduled as recommended and may lead to an underestimation of the prevalence of hypertension. Given this clinical settings, the rules to classify BP were widened to a 36‐month study period that allowed for the inclusion of BP measurements from 3 regular annual visits. The use of the first 4 consecutive BPs allowed one BP to be an outlier below classification requirements. We classified BP using the recommendations of the Fourth Report On the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program (NHBPEP)14 combined with the recommendations for adults of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7).15 Prehypertension was defined as at least one BP between the 90th percentile and <95th percentile (or ≥120/80 mm Hg even if lower than the 90th percentile) of age, sex, and height BP distribution charts. Because of high variability of BP in this age group, the NHBPEP definition of hypertension in children and adolescents requires a BP ≥95th percentile (or ≥140/90 mm Hg even if lower than the 95th percentile) on at least 3 separate occasions. We classified youth with 1 or 2 BPs ≥95th percentile as “blood pressure in the hypertensive range.” As previously described, patients with a diagnosis of essential hypertension and at least one prescription of antihypertensive drug were classified as having hypertension if there was no information in the EHR to suggest a different diagnosis.

Body Weight and Height

Body weight and height were routinely measured and extracted from the EHR. BMI was calculated as weight (kilograms) divided by the square of the height (meters). Definitions of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents are based on the sex‐specific BMI‐for‐age growth charts developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.16 Because BMI‐for‐age cross the adult thresholds for overweight and obesity, which may lead to an underestimation of overweight and obesity in adolescents older than 15 years, the definitions were combined with the World Health Organization definitions for overweight and obesity in adults.16, 17, 18 Children were categorized as underweight (BMI‐for‐age <5th percentile), normal weight (BMI‐for‐age ≥5th to <85th percentile), overweight (BMI‐for‐age ≥85th to <95th percentile or a BMI ≥25 to <30 kg/m2), moderately obese (BMI‐for‐age ≥95th to <1.2×95th percentile or a BMI ≥30 to <35 kg/m2), and extremely obese (BMI‐for‐age ≥1.2×95th percentile or a BMI ≥35 kg/m2). Based on a validation study including 15,000 patients with 45,980 medical encounters, the estimated error rate in weight and height data was <0.4%.19

Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status

We obtained race and ethnicity information from health plan administrative records and birth records. We hierarchically categorized race/ethnicity as Hispanic (regardless of race), non‐Hispanic white, black, Asian or Pacific Islander, and other, multiple, or unknown race/ethnicity combined. In a validation study comparing health plan administrative records and birth certificate records of 325,810 children,20 the positive predictive values (PPVs) were 89.3% for Hispanic ethnicity, 95.6% for white, 86.6% for black, 73.8% for Asian/Pacific Islander, 51.8% for other, and 1.2% for multiple race/ethnicity.

In cases for which race and ethnicity information was unknown (31.7%), administrative records were supplemented by an imputation algorithm that used surname lists and address information derived from the US Census Bureau.21, 22, 23 Hispanic ethnicity and Asian race were assigned based on surnames. For blacks and non‐Hispanic whites, the child's home address was used to link racial/ethnic information from the US Census Bureau. Race/ethnicity was hierarchically assigned using probability cutoffs of >50% for Asian surname, >50% for Hispanic surname, >75% for black race from geocoding, and white race >45% from geocoding if no other assignment could be made before. The specificity and PPV were >98% for all races/ethnicities.8

To assess socioeconomic status, we used neighborhood education, which was estimated from geocoded addresses linked to 2010 US census data at the block level.24

Statistical Analysis

Differences in the distribution of demographic characteristics for the analytical cohort, as well as youth excluded due to missing BP measures, among weight classes were assessed using the chi‐square test. The prevalence of high BP was estimated for the entire cohort and by sex (boys/girls), age group (6–11 years, 12–17 years), race/ethnicity (non‐Hispanic white, Hispanic, black, Asian or Pacific Islander, other or unknown), and state subsidized healthcare (yes/no). The prevalence was expressed as a percentage with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For outcomes with high frequency, the odds ratio derived from logistic regression can overestimate the prevalence ratio. Hence, we examined the associations of high BP with weight class by using log‐binomial regression models to estimate crude prevalence ratios (PRs) and corresponding 95% CIs as well as adjusted PRs after adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. In order to detect the possible interactions between weight class and sex, age, and race on prehypertension and hypertension, we used two log‐binomial regression models: (1) the multivariable model stratified by age, sex, or race, (2) additionally including 2‐way interaction terms into the model.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to predict prehypertension (or higher), BP in the hypertensive range (or higher), and hypertension by BMI‐for‐age percentile. The area under the curve (AUC) or model c statistic and corresponding 95% CIs are provided. The optimal threshold was chosen where accuracy measures (Youden Index, total accuracy) were maximized and total misclassification error was minimized.25 The Youden Index (J=Sensitivity + Specificity −1) is the maximum difference between the ROC curve and the diagonal or chance line, and determines the cut point that optimizes the ability to differentiate between individuals with the outcome of interest and those without this outcome assuming an equal weight for sensitivity and specificity. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographics of the Study Population

Approximately half of the study population was Hispanic (Table 1). Extremely obese youth were more likely to be male, Hispanic or black, and to live in a census block with a higher proportion of adult residence with low educational attainment. Compared with youth excluded from the analysis because they did not have 3 independent BPs in the study period (n=228,331), the study cohort was similar in the distribution of sex, race/ethnicity, neighborhood education, and neighborhood income (data not shown). However, youth excluded from the analysis were slightly younger and, for a significant proportion of these youth (37.4%), the membership with medical care coverage at KPSC ended before the end of the study period.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population According to Weight Classa

| Total | Underweight | Normal Weight | Overweight | Moderately Obese | Extremely Obese | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | ||

| Total | 237,248 (100.0) | 5252 (2.2) | 135,705 (57.2) | 43,282 (18.2) | 35,004 (14.8) | 18,005 (7.6) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 115,991 (48.9) | 2775 (52.8) | 62,962 (46.4) | 20,758 (47.1) | 19,274 (55.1) | 10,586 (58.8) | <.0001 |

| Female | 121,257 (51.1) | 2477 (47.2) | 72,743 (53.6) | 22,888 (52.9) | 15,730 (44.9) | 7419 (41.2) | |

| Age group, y | |||||||

| 6–11 | 98,175 (41.4) | 2553 (48.6) | 53,403 (39.6) | 17,823 (40.2) | 16,605 (47.4) | 7791 (43.3) | <.001 |

| 12–17 | 139,073 (58.6) | 2699 (51.4) | 82,302 (60.7) | 25,459 (58.8) | 18,399 (52.6) | 10,214 (56.7) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 57,849 (24.4) | 1597 (30.4) | 38,027 (28.0) | 9532 (22.0) | 6173 (17.6) | 2520 (14.0) | <.0001 |

| Hispanic | 119,667 (50.4) | 2.068 (39.4) | 61,888 (45.6) | 23,284 (53.8) | 21,052 (60.1) | 11,375 (63.2) | |

| Black | 16,044 (6.8) | 272 (5.2) | 8937 (6.6) | 2959 (6.8) | 2335 (6.8) | 1541 (8.6) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 14,582 (6.2) | 605 (11.5) | 9447 (7.0) | 2292 (5.3) | 1623 (4.6) | 615 (3.4) | |

| Other/unknown | 29,106 (12.3) | 710 (13.5) | 17,406 (12.8) | 5215 (12.1) | 3821 (10.9) | 1954 (10.9) | |

| Neighborhood educationb | |||||||

| Less than high school | 64,798 (27.3) | 1.230 (23.4) | 34,277 (25.3) | 12,301 (28.4) | 10,894 (31.1) | 6096 (33.9) | <.0001 |

| High school graduate | 50,552 (21.3) | 1091 (20.8) | 28,582 (21.1) | 9276 (21.4) | 7618 (21.8) | 3982 (22.1) | |

| Some college/associate degree | 72,737 (30.7) | 1665 (31.7) | 42,526 (31.3) | 13,122 (30.3) | 10,293 (29.4) | 5130 (28.5) | |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 49,160 (20.7) | 1266 (24.1) | 30,319 (22.3) | 8580 (19.8) | 6198 (17.6) | 2797 (15.5) | |

Definition of weight class: underweight was defined as body mass index (BMI)‐for‐age ≤5th percentile, overweight as BMI‐for‐age ≥85th percentile or a BMI ≥25 kg/m2, moderate obesity as ≥95th percentile or a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, and extreme obesity ≥1.2×95th percentile or a BMI ≥35 kg/m2.

Neighborhood education estimated from geocoded addresses linked to 2010 US census data at the block level.

BMI and BP

The prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension in the total sample were 31.4% and 2.1%, respectively (Table 2). A significant proportion of youth had 1 (16.6%) or 2 (4.8%) BP measurements in the hypertensive range. Among youth with high BP, 75.3% had an isolated elevated systolic BP, 14.6% had an isolated elevated diastolic BP, and 10.0% had 1 elevated systolic and 1 elevated diastolic BP.

Table 2.

Prevalence (95% CI) of High BP in Youth According to Weight Classa by Sex and Age Group

| Group | Prehypertension | BP in the Hypertensive Range | Hypertension | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One BP ≥95th Percentilea | Two BP ≥95th Percentile | |||||||

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |

| Total population | 74,501 | 31.4 (31.2–31.6) | 39,502 | 16.6 (16.5–16.8) | 11,373 | 4.8 (4.7–4.9) | 5039 | 2.1 (2.1–2.2) |

| Underweight | 1265 | 24.1 (22.9–25.2) | 599 | 11.4 (10.6–12.3) | 121 | 2.3 (1.9–2.7) | 31 | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) |

| Normal weight | 40,558 | 29.9 (29.6–30.1) | 17,615 | 13.0 (12.8–13.2) | 3639 | 2.7 (2.6–2.8) | 1184 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| Overweight | 14,809 | 34.2 (33.8–34.7) | 7850 | 18.1 (17.8–18.5) | 2189 | 5.1 (4.9–5.3) | 847 | 2.0 (1.8–2.1) |

| Moderately obese | 12,161 | 34.7 (34.2–35.2) | 8274 | 23.6 (23.2–24.1) | 2882 | 8.2 (8.0–8.5) | 1330 | 3.8 (3.6–4.0) |

| Extremely obese | 5708 | 31.7 (31.0–32.4) | 5164 | 28.7 (28.0–29.3) | 2542 | 14.1 (13.6–14.6) | 1647 | 9.2 (8.7–9.6) |

| Boys | 42,981 | 37.1 (36.8–37.3) | 20,242 | 17.5 (17.2–17.7) | 5894 | 5.1 (5.0–5.2) | 2653 | 2.3 (2.2–2.4) |

| Underweight | 783 | 28.2 (26.5–29.9) | 306 | 11.0 (9.9–12.2) | 73 | 2.6 (2.0–3.2) | 16 | 0.6 (0.3–0.9) |

| Normal weight | 23,062 | 36.6 (36.3–37.0) | 8485 | 13.5 (13.2–13.7) | 1807 | 2.9 (2.7–3.0) | 569 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

| Overweight | 8091 | 39.7 (39.0–40.3) | 3851 | 18.9 (18.4–19.4) | 1024 | 5.0 (4.7–5.3) | 406 | 2.0 (1.8–2.2) |

| Moderately obese | 7455 | 38.7 (38.0–39.4) | 4532 | 23.5 (22.9–24.1) | 1505 | 7.8 (7.4–8.2) | 709 | 3.7 (3.4–3.9) |

| Extremely obese | 3590 | 33.9 (33.0–34.8) | 3068 | 28.9 (28.1–29.9) | 1485 | 14.0 (13.3–14.7) | 953 | 9.0 (8.5–9.6) |

| Girls | 31,520 | 26.0 (25.8–26.4) | 19,260 | 15.9 (15.7–16.1) | 5479 | 4.5 (4.4–4.6) | 2386 | 2.0 (1.9–2.1) |

| Underweight | 482 | 19.5 (17.9–21.0) | 293 | 11.8 (10.6–13.1) | 48 | 1.9 (1.4–2.5) | 15 | 0.6 (0.3–0.9) |

| Normal weight | 17,496 | 24.1 (23.7–24.4) | 9130 | 12.6 (12.3–12.8) | 1832 | 2.5 (2.4–2.6) | 615 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| Overweight | 6718 | 29.4 (28.8–29.9) | 3999 | 17.5 (17.0–18.0) | 1165 | 5.1 (4.8–5.4) | 441 | 1.9 (1.8–2.1) |

| Moderately obese | 4706 | 29.9 (29.2–30.6) | 3742 | 23.8 (23.1–24.5) | 1377 | 8.8 (8.3–9.2) | 621 | 4.0 (3.6–4.3) |

| Extremely obese | 2118 | 28.6 (27.5–29.6) | 2096 | 28.3 (27.2–29.3) | 1057 | 14.3 (13.5–15.0) | 694 | 9.4 (8.7–10.0) |

| Aged 6–11 y | 19,783 | 20.2 (19.9–20.4) | 18,221 | 18.6 (18.3–18.8) | 5280 | 5.4 (5.2–5.5) | 2127 | 2.2 (2.1–2.3) |

| Underweight | 430 | 16.8 (15.4–18.3) | 359 | 14.1 (12.7–15.4) | 48 | 2.7 (2.0–3.3) | 15 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) |

| Normal weight | 9586 | 17.9 (17.6–18.3) | 8136 | 15.2 (14.9–15.5) | 1832 | 3.2 (3.1–3.4) | 615 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| Overweight | 3914 | 22.0 (21.4–22.6) | 3425 | 19.2 (18.6–19.8) | 1165 | 5.5 (5.1–5.8) | 441 | 1.8 (1.6–2.0) |

| Moderately obese | 4022 | 24.2 (23.6–24.9) | 4010 | 24.2 (23.5–24.8) | 1377 | 8.5 (8.1–8.9) | 621 | 3.5 (3.2–3.8) |

| Extremely obese | 1831 | 23.5 (22.6–24.4) | 2291 | 29.4 (28.4–30.4) | 1057 | 14.4 (13.6–15.2) | 694 | 8.6 (7.9–9.2) |

| Aged 12–19 y | 54,718 | 39.3 (30.1–39.6) | 21,281 | 15.3 (15.1–15.5) | 6093 | 4.4 (4.3–4.5) | 2912 | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) |

| Underweight | 482 | 30.9 (29.2–32.7) | 293 | 8.9 (7.8–9.8) | 48 | 2.0 (1.4–2.5) | 15 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) |

| Normal weight | 17,496 | 37.6 (37.3–38.0) | 9130 | 11.5 (11.3–11.7) | 1832 | 2.4 (2.2–2.5) | 615 | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) |

| Overweight | 6718 | 42.8 (42.2–43.4) | 3999 | 17.4 (16.9–17.9) | 1165 | 4.8 (4.5–5.0) | 441 | 2.1 (1.9–2.2) |

| Moderately obese | 4706 | 44.2 (43.5–45.0) | 3742 | 23.2 (22.6–23.8) | 1377 | 8.0 (7.6–8.4) | 621 | 4.1 (3.8–4.4) |

| Extremely obese | 2118 | 38.0 (37.0–38.9) | 2096 | 28.1 (27.3–29.0) | 1057 | 13.9 (13.2–14.6) | 694 | 9.6 (9.0–10.2) |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 20,166 | 34.9 (34.5–35.3) | 9106 | 15.7 (15.4–16.0) | 2405 | 4.2 (4.0–4.3) | 1024 | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) |

| Underweight | 439 | 27.5 (25.3–29.7) | 174 | 10.9 (9.4–12.4) | 40 | 2.5 (1.7–3.3) | 10 | 0.6 (0.2–1.0) |

| Normal weight | 12,862 | 33.8 (33.4–34.3) | 4967 | 13.1 (12.7–13.4) | 1005 | 2.6 (2.5–2.8) | 355 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

| Overweight | 3650 | 38.3 (37.3–39.3) | 1718 | 18.0 (17.3–18.8) | 508 | 5.3 (4.9–5.8) | 191 | 2.0 (1.7–2.3) |

| Moderately obese | 2295 | 37.2 (36.0–38.4) | 1538 | 24.9 (23.8–26.0) | 522 | 8.5 (7.8–9.2) | 248 | 4.0 (3.5–4.5) |

| Extremely obese | 920 | 36.5 (34.6–38.4) | 709 | 28.1 (26.4–29.9) | 330 | 13.1 (11.8–14.4) | 220 | 8.7 (7.6–9.8) |

| Hispanic | 35,443 | 29.6 (29.4–29.9) | 20,467 | 17.1 (16.9–17.3) | 6078 | 5.1 (5.0–5.2) | 2814 | 2.4 (2.3–2.4) |

| Underweight | 433 | 20.9 (19.2–22.7) | 223 | 10.8 (9.5–12.1) | 43 | 2.1 (1.5–2.7) | 15 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) |

| Normal weight | 16,953 | 27.4 (27.0–27.7) | 7925 | 12.8 (12.5–13.1) | 1587 | 2.6 (2.4–2.7) | 521 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| Overweight | 7538 | 32.4 (31.8–33.0) | 4147 | 17.8 (17.3–18.3) | 1115 | 4.8 (4.5–5.1) | 435 | 1.9 (1.7–2.0) |

| Moderately obese | 7051 | 33.5 (32.9–34.1) | 4905 | 23.3 (22.7–23.9) | 1708 | 8.1 (7.7–8.5) | 778 | 3.7 (3.4–4.0) |

| Extremely obese | 3468 | 30.5 (29.6–31.3) | 3267 | 28.7 (27.9–29.6) | 1625 | 14.3 (10.9–14.2) | 1065 | 9.4 (8.8–9.9) |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 5240 | 32.7 (31.9–33.4) | 2730 | 17.0 (16.4–17.6) | 2.814 | 2.4 (2.3–2.4) | 314 | 2.0 (1.7–2.2) |

| Underweight | 63 | 23.2 (18.2–28.2) | 52 | 19.1 (14.4–23.8) | 8 | 2.9 (0.9–4.9) | 1 | 0.4 (0.0–1.1) |

| Normal weight | 2773 | 31.0 (30.1–32.0) | 1155 | 12.9 (12.2–13.6) | 253 | 2.8 (2.5–3.2) | 68 | 0.8 (0.6–0.9) |

| Overweight | 1057 | 35.7 (34.5–38.4) | 553 | 18.7 (17.3–20.1) | 128 | 4.3 (3.6–5.1) | 47 | 1.6 (1.1–2.0) |

| Moderately obese | 851 | 36.5 (34.5–38.4) | 518 | 22.2 (20.5–23.9) | 169 | 7.2 (6.2–8.3) | 74 | 3.2 (2.5–3.9) |

| Extremely obese | 496 | 32.2 (28.9–34.5) | 452 | 29.3 (27.1–31.6) | 193 | 12.5 (10.9–14.2) | 124 | 8.1 (6.7–9.4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4169 | 28.6 (27.9–29.3) | 2454 | 16.8 (16.2–17.4) | 729 | 5.0 (5.7–5.4) | 347 | 2.4 (2.1–2.6) |

| Underweight | 152 | 25.1 (21.7–28.6) | 65 | 10.7 (8.3–13.2) | 11 | 1.8 (0.8–2.9) | 3 | 0.5 (0.0–1.1) |

| Normal weight | 2556 | 27.1 (26.2–28.0) | 1318 | 14.0 (13.3–14.7) | 302 | 3.2 (2.8–3.6) | 111 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| Overweight | 738 | 32.2 (30.3–34.1) | 461 | 20.1 (18.5–21.8) | 148 | 6.5 (5.5–7.5) | 75 | 3.3 (2.5–4.0) |

| Moderately obese | 549 | 33.8 (31.5–36.1) | 429 | 26.4 (24.3–28.6) | 159 | 9.8 (8.4–11.2) | 87 | 5.4 (4.3–6.5) |

| Extremely obese | 174 | 28.3 (24.7–31.9) | 181 | 29.4 (25.8–33.0) | 109 | 17.7 (14.7–20.7) | 71 | 11.5 (9.2–14.1) |

| Other/unknown | 9483 | 32.6 (32.0–33.1) | 4745 | 16.3 (15.9–16.7) | 1410 | 4.8 (4.6–5.1) | 540 | 1.9 (1.7–2.0) |

| Underweight | 178 | 25.1 (21.9–28.3) | 85 | 12.0 (9.6–14.4) | 19 | 2.7 (1.5–3.9) | 2 | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) |

| Normal weight | 5414 | 31.1 (30.4–31.8) | 2250 | 12.9 (12.4–13.4) | 492 | 2.8 (2.6–3.1) | 129 | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

| Overweight | 1826 | 35.0 (33.7–36.3) | 971 | 18.6 (17.6–19.7) | 290 | 5.6 (4.9–6.2) | 99 | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) |

| Moderately obese | 1415 | 37.0 (35.5–36.1) | 884 | 23.1 (21.8–24.5) | 324 | 8.5 (7.6–9.4) | 143 | 3.7 (3.1–4.3) |

| Extremely obese | 650 | 33.3 (31.2–35.4) | 555 | 28.4 (26.4–30.4) | 285 | 14.6 (13.0–16.2) | 167 | 8.6 (7.3–9.8) |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval.

Definition of weight class: underweight was defined as body mass index (BMI)‐for‐age ≤5th percentile, overweight as BMI‐for‐age ≥85th percentile or a BMI ≥25 kg/m2, moderate obesity as ≥95th percentile or a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, and extreme obesity ≥1.2×95th percentile or a BMI ≥35 kg/m2.

The prevalence of high BP was higher with a higher BMI category across sexes and age groups. For example, the prevalence of hypertension was 0.6% in underweight and 0.9% in normal weight youth and 9.2% in extremely obese youth. Extremely obese youth were 10.58 (95% CI, 9.75–11.28) times and moderately obese 4.35 (95% CI, 4.03–4.71) times more likely to have hypertension than their normal weight counterparts (Table 3). This association remained unchanged after adjusting for sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Sex and race/ethnicity did not modify the association between body weight and high BP (both P values >.30). However, the association between body weight and high BP was marginally but significantly (P<.001) stronger in those aged 12 to 17 than in those aged 6 to 11 years.

Table 3.

Crude and Adjusted PR and 95% CI of Prehypertension, BP in the Hypertensive Range, and Hypertension According to Weight Status

| Degree of BP Elevation | Underweight | Normal Weight | Overweight | Moderately Obese | Extremely Obese | P Value for Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | ||||||

| Prehypertension (N=74,501) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 1265 | 40,558 | 14,809 | 12,161 | 5708 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.78 (0.75–0.82) | 1.0 | 1.28 (1.26–1.29) | 1.51 (1.49–1.53) | 1.84 (1.81–1.87) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.78 (0.74–0.81) | 1.0 | 1.29 (1.27–1.31) | 1.49 (1.47–1.51) | 1.65 (1.63–1.67) | <.001 |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=39,502) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 599 | 17,615 | 7850 | 8274 | 5164 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.87 (0.81–0.94) | 1.0 | 1.45 (1.41–1.48) | 2.00 (1.95–2.04) | 2.78 (2.71–2.85) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.85 (0.80–0.92) | 1.0 | 1.45 (1.41–1.48) | 1.97 (1.93–2.02) | 2.76 (2.69–2.84) | <.001 |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=11,373) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 121 | 3639 | 2189 | 2882 | 2542 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.86 (0.72–1.02) | 1.0 | 1.91 (1.81–2.01) | 3.16 (3.02–3.32) | 5.74 (5.48–6.03) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.83 (0.70–1.00) | 1.0 | 1.92 (1.82–2.02) | 3.16 (3.01–3.32) | 5.81 (5.53–6.10) | <.001 |

| Hypertension (n=5039) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 31 | 1184 | 847 | 1330 | 1647 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.68 (0.47–0.97) | 1.0 | 2.24 (2.06–2.45) | 4.35 (4.03–4.71) | 10.48 (9.75–11.28) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.67 (0.47–0.95) | 1.0 | 2.27 (2.08–2.47) | 4.43 (4.10–4.79) | 10.76 (9.99–11.59) | <.001 |

| Boys | ||||||

| Prehypertension (n=42,981) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 783 | 23,062 | 8091 | 7455 | 3590 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.74 (0.70–0.79) | 1.0 | 1.21 (1.19–1.23) | 1.34 (1.32–1.37) | 1.60 (1.56–1.63) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.74 (0.70–0.78) | 1.0 | 1.23 (1.21–1.25) | 1.38 (1.36–1.40) | 1.53 (1.51–1.55) | <.001 |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=20,242) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 306 | 8485 | 3851 | 4532 | 3068 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.81 (0.73–0.91) | 1.0 | 1.45 (1.40–1.50) | 1.90 (1.84–1.96) | 2.69 (2.60–2.78) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.91 (0.72–0.90) | 1.0 | 1.44 (1.40–1.49) | 1.88 (1.82–1.94) | 2.68 (2.59–2.77) | <.001 |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=5894) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 73 | 1807 | 1024 | 1505 | 1485 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.91 (0.73–1.15) | 1.0 | 1.77 (1.64–1.91) | 2.80 (2.62–2.99) | 5.32 (4.99–5.68) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.90 (0.71–1.13) | 1.0 | 1.77 (1.64–1.90) | 2.79 (2.61–2.98) | 5.34 (4.99–5.70) | <.001 |

| Hypertension (n=2653) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 16 | 569 | 406 | 709 | 953 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.64 (0.39–1.05) | 1.0 | 2.20 (1.94–2.50) | 4.07 (3.65–4.54) | 9.96 (9.00–11.03) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.63 (0.38–1.03) | 1.0 | 2.20 (1.94–2.20) | 4.07 (3.65–4.55) | 9.97 (8.99–11.05) | <.001 |

| Girls | ||||||

| Prehypertension (n=31,520) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 482 | 17,496 | 6718 | 4706 | 2118 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.79 (0.73–0.86) | 1.0 | 1.36 (1.33–1.39) | 1.36 (1.61––1.69) | 2.07 (2.01–2.14) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.84 (0.77–0.91) | 1.0 | 1.39 (1.35–1.42) | 1.74 (1.70–1.78) | 2.13 (2.07–2.13) | <.001 |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=19,260) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 293 | 9130 | 3999 | 3742 | 2096 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.93 (0.84–1.04) | 1.0 | 1.45 (1.40–1.50) | 2.10 (2.03–2.17) | 2.85 (2.74–2.96) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.89 (0.80–1.00) | 1.0 | 1.45 (1.40–1.50) | 2.07 (2.00–2.14) | 2.84 (2.73–2.95) | <.001 |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=5479) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 48 | 1832 | 1165 | 1377 | 1057 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.91 (0.73–1.15) | 1.0 | 1.77 (1.64–1.91) | 2.80 (2.62–2.99) | 5.32 (4.99–5.68) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.90 (0.71–1.13) | 1.0 | 1.77 (1.64–1.91) | 2.79 (2.61–2.98) | 5.34 (4.99–5.70) | <.001 |

| Hypertension (n=2386) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 15 | 615 | 441 | 621 | 694 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.72 (0.43–1.19) | 1.0 | 2.28 (2.02–2.57) | 4.67 (4.18–5.21) | 11.06 (9.95–12.30) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.69 (0.41–1.15) | 1.0 | 2.32 (2.05–2.62) | 4.77 (4.27–5.34) | 11.48 (10.31–12.78) | <.001 |

| Aged 6–11 y | ||||||

| Prehypertension (n=19,783) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 430 | 10,670 | 1360 | 1343 | 2312 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.92 (0.84–1.00) | 1.0 | 1.34 (1.30–1.38) | 1.70 (1.65–1.75) | 2.21 (2.13–2.30) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.91 (0.83–0.99) | 1.0 | 1.35 (1.31–1.39) | 1.72 (1.67–1.77) | 2.24 (2.16–2.33) | <.001 |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=18,221) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 359 | 8136 | 3425 | 4010 | 2291 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.92 (0.83–1.01) | 1.0 | 1.30 (1.26–1.35) | 1.72 (1.67–1.78) | 2.40 (2.31–2.49) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.91 (0.82–1.00) | 1.0 | 1.31 (1.26–1.36) | 1.75 (1.69–1.81) | 2.44 (2.35–2.54) | <.001 |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=5280) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 68 | 1707 | 973 | 1409 | 1123 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.83 (0.65–1.06) | 1.0 | 1.72 (1.59–1.86) | 2.72 (2.54–2.91) | 4.88 (4.55–5.24) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.82 (0.64–1.04) | 1.0 | 1.74 (1.61–1.88) | 2.77 (2.59–2.97) | 5.05 (4.69–5.42) | <.001 |

| Hypertension (n=2127) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 19 | 544 | 321 | 576 | 667 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.73 (0.46–1.15) | 1.0 | 1.77 (1.54–2.03) | 3.41 (3.03–3.82) | 8.40 (7.529.39) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.71 (0.45–1.12) | 1.0 | 1.79 (1.56–2.05) | 3.49 (3.10–3.92) | 8.78 (7.84–9.82) | <.001 |

| Aged 12–19 y | ||||||

| Prehypertension (n=54,718) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 835 | 30,972 | 10,895 | 8139 | 3877 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.79 (0.75–0.84) | 1.0 | 1.28 (1.26–1.30) | 1.55 (1.53–1.57) | 1.78 (1.75–1.81) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.73 (0.69–0.77) | 1.0 | 1.27 (1.25–1.29) | 1.42 (1.41–1.44) | 1.56 (1.53–1.58) | <.001 |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=21,281) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 240 | 9479 | 4425 | 4264 | 2873 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.77 (0.68–0.87) | 1.0 | 1.57 (1.52–1.62) | 2.22 (2.15–2.29) | 3.09 (2.99–3.20) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.75 (0.67–0.85) | 1.0 | 1.57 (1.52–1.63) | 2.21 (2.14–2.28) | 3.07 (2.96–3.18) | <.001 |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=6093) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 53 | 1932 | 1216 | 1473 | 1419 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.83 (0.64–1.09) | 1.0 | 2.06 (1.92–2.21) | 3.53 (3.30–3.77) | 6.50 (6.09–6.93) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.81 (0.62–1.07) | 1.0 | 2.08 (1.94–2.23) | 3.53 (3.30–3.77) | 6.51 (6.09–6.95) | <.001 |

| Hypertension (n=2912) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 12 | 640 | 526 | 754 | 980 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.57 (0.32–1.01) | 1.0 | 2.66 (2.37–2.98) | 5.27 (4.75–5.85) | 12.34 (11.19–13.60) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.56 (0.32–0.99) | 1.0 | 2.68 (2.39–3.00) | 5.29 (4.76–5.87) | 12.44 (11.27–13.74) | <.001 |

| Non‐Hispanic whites | ||||||

| Prehypertension (n=20,166) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 439 | 12,862 | 3650 | 2295 | 920 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) | 1.0 | 1.26 (1.23–1.30) | 1.46 (1.42–1.51) | 1.80 (1.73–1.86) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.79 (0.74–0.85) | 1.0 | 1.25 (1.23–1.28) | 1.42 (1.39–1.45) | 1.55 (1.51–1.59) | <.001 |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=9106) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 174 | 4967 | 1718 | 1538 | 709 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.83 (0.72–0.92) | 1.0 | 1.44 (1.37–1.51) | 2.10 (2.00–2.21) | 2.84 (2.74–2.94) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.81 (0.71–0.94) | 1.0 | 1.43 (1.36–1.50) | 2.07 (1.97–2.18) | 2.78 (2.69–2.88) | <.001 |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=2405) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 40 | 1005 | 508 | 522 | 330 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.81 (0.60–1.09) | 1.0 | 1.89 (1.75–2.03) | 3.26 (3.05–3.48) | 6.09 (5.71–6.51) | <.001 |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.80 (0.59–1.08) | 1.0 | 1.88 (1.75–2.03) | 3.21 (3.01–3.44) | 6.03 (5.64–6.44) | <.001 |

| Hypertension (n=1024) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 10 | 355 | 191 | 248 | 220 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.67 (0.36–1.26) | 1.0 | 2.15 (1.80–2.56) | 4.30 (3.67–5.05) | 9.35 (7.94–11.01) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.68 (0.36–1.27) | 1.0 | 2.15 (1.81–2.56) | 4.37 (3.72–5.13) | 9.49 (8.06–11.18) | |

| Hispanic | ||||||

| Prehypertension (n=35,443) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 433 | 16,953 | 7538 | 7051 | 3468 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.74 (0.68–0.81) | 1.0 | 1.31 (1.28–1.34) | 1.58 (1.55–1.61) | 1.96 (1.91–2.00) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.74 (0.68–0.80) | 1.0 | 1.31 (1.29–1.34) | 1.54 (1.51–1.57) | 1.74 (1.71–1.78) | |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=20,467) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 223 | 7925 | 4147 | 4905 | 3267 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.84 (0.74–0.95) | 1.0 | 1.44 (1.39–1.49) | 1.99 (1.93–2.06) | 2.84 (2.74–2.94) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.83 (0.73–0.94) | 1.0 | 1.44 (1.39–1.49) | 1.96 (1.89–2.02) | 2.78 (2.69–2.88) | |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=6078) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 43 | 1587 | 1115 | 1708 | 1625 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.81 (0.60–1.09) | 1.0 | 1.89 (1.75–2.03) | 3.26 (3.05–3.48) | 6.09 (5.71–6.51) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.80 (0.59–1.08) | 1.0 | 1.88 (1.75–2.03) | 3.21 (3.01–3.44) | 6.03 (5.64–6.44) | |

| Hypertension (n=2814) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 15 | 521 | 435 | 778 | 1065 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.86 (0.52–1.44) | 1.0 | 2.22 (1.96–2.52) | 4.39 (3.93–4.90) | 11.12 (10.03–12.33) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.86 (0.52–1.44) | 1.0 | 2.22 (1.96–2.52) | 4.39 (3.93–4.90) | 11.05 (9.96–12.25) | |

| Non‐Hispanic black | ||||||

| Prehypertension (n=5240) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 63 | 2773 | 1057 | 851 | 496 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.80 (0.65–0.99) | 1.0 | 1.27 (1.21–1.34) | 1.45 (1.38–1.54) | 1.73 (1.63–1.84) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.81 (0.66–0.99) | 1.0 | 1.31 (1.25–1.38) | 1.42 (1.35–1.49) | 1.59 (1.52–1.67) | |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=2730) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 52 | 1155 | 553 | 518 | 452 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 1.47 (1.15–1.89) | 1.0 | 1.48 (1.35–1.62) | 1.85 (1.68–2.03) | 2.75 (2.52–3.02) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 1.46 (1.14–1.88) | 1.0 | 1.47 (1.35–1.62) | 1.83 (1.67–2.01) | 2.75 (2.51–3.01) | |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=751) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 8 | 253 | 128 | 169 | 193 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 1.03 (0.52–2.07) | 1.0 | 1.54 (1.25–1.90) | 2.62 (2.17–3.17) | 4.77 (3.99–5.71) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 1.05 (0.52–2.09) | 1.0 | 1.53 (1.24–1.89) | 2.61 (2.16–3.15) | 4.75 (3.97–5.68) | |

| Hypertension (n=314) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 1 | 68 | 47 | 74 | 124 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.48 (0.07–3.47) | 1.0 | 2.09 (1.44–3.02) | 4.17 (3.01–5.77) | 10.58 (7.91–14.14) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.50 (0.07–3.56) | 1.0 | 2.07 (1.43–3.00) | 4.15 (3.00–5.76) | 10.48 (7.84–14.02) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | ||||||

| Prehypertension (n=4169) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 152 | 2556 | 738 | 549 | 174 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.87 (0.76–1.00) | 1.0 | 1.39 (1.30–1.47) | 1.75 (1.64–1.86) | 2.07 (1.89–2.26) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.86 (0.75–0.98) | 1.0 | 1.36 (1.28–1.43) | 1.63 (1.55–1.72) | 1.77 (1.66–1.88) | |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=2454) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 65 | 1318 | 461 | 429 | 181 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.75 (0.60–0.95) | 1.0 | 1.53 (1.39–1.68) | 2.14 (1.95–2.34) | 2.85 (2.52–3.22) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.74 (0.58–0.93) | 1.0 | 1.49 (1.36–1.64) | 2.01 (1.83–2.21) | 2.69 (2.38–3.04) | |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=729) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 11 | 302 | 148 | 159 | 109 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.56 (0.31–1.03) | 1.0 | 2.06 (1.70–2.50) | 3.20 (2.66–3.85) | 6.19 (5.07–7.57) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.55 (0.30–1.00) | 1.0 | 2.02 (1.67–2.45) | 3.04 (2.52–3.67) | 5.90 (4.81–7.24) | |

| Hypertension (n=347) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 3 | 111 | 75 | 87 | 71 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.42 (0.13–1.32) | 1.0 | 2.79 (2.09–3.72) | 4.56 (3.46–6.01) | 9.83 (7.38–13.08) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.41 (0.13–1.30) | 1.0 | 2.74 (2.05–3.66) | 4.36 (3.30–5.77) | 9.39 (7.01–12.56) | |

| Other/unknown | ||||||

| Prehypertension (n=9483) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 178 | 5414 | 1826 | 1415 | 650 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.79 (0.70–0.90) | 1.0 | 1.27 (1.22–1.32) | 1.54 (1.48–1.60) | 1.84 (1.76–1.93) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.78 (0.69–0.88) | 1.0 | 1.28 (1.23–1.32) | 1.47 (1.42–1.52) | 1.63 (1.58–1.69) | |

| One BP in hypertensive range (n=4745) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 85 | 2250 | 971 | 884 | 555 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.92 (0.75–1.13) | 1.0 | 1.50 (1.40–1.61) | 1.97 (1.84–2.11) | 2.76 (2.55–2.98) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.91 (0.74–1.11) | 1.0 | 1.49 (1.39–1.60) | 1.94 (1.81–2.07) | 2.73 (2.53–2.95) | |

| Two BPs in hypertensive range (n=1410) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 19 | 492 | 290 | 324 | 285 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.94 (0.60–1.48) | 1.0 | 1.99 (1.73–2.29) | 3.09 (2.70–3.54) | 5.60 (4.88–6.43) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.94 (0.60–1.48) | 1.0 | 1.99 (1.72–2.29) | 3.09 (2.70–3.54) | 5.63 (4.91–6.47) | |

| Hypertension (n=540) | ||||||

| No. of cases | 2 | 129 | 99 | 143 | 167 | |

| Crude PR (95% CI) | 0.38 (0.09–1.53) | 1.0 | 2.56 (1.97–3.32) | 5.05 (3.99–6.39) | 11.53 (9.21–11.44) | |

| Adjusted PR (95% CI)a | 0.39 (0.10–1.57) | 1.0 | 2.57 (1.98–3.33) | 5.17 (4.08–6.54) | 11.78 (9.40–14.76) | |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio.

Adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Thresholds for BMI‐for‐Age as a Predictor of High‐Grade Prehypertension and Hypertension

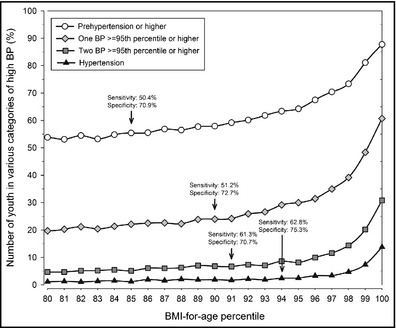

The AUCs for the prediction of prehypertension or higher, 1 BP in the hypertensive range (ie, ≥95th percentile) or higher, 2 BPs in the hypertensive range or higher, and hypertension by BMI‐per‐age percentile are shown in Figure 2 (all AUCs: P<.001). The Youden Index was maximal at the 85th percentile, 90th percentile, 91st percentile, and 94th percentile of BMI‐for‐age for having at least prehypertension, 1 BP in the hypertensive range, 2 BPs in the hypertensive range and hypertension, respectively (Figure 2). The sensitivity and specificity of the optimal body weight threshold ranged between 50.4% and 70.9%, respectively, for prehypertension and 62.8% and 75.3% for hypertension, respectively (Figure 3). The prevalence of high BP increased linearly with respect to BMI up to the 96th percentile and then increased steeply above the 97th percentile.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristics and operating characteristics for different levels of high blood pressure. BMI indicates body mass index.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of high blood pressure in youth by body mass index (BMI)‐for‐age percentile. Sensitivity and specificity are given for the optimal thresholds (Youden Index=maximal). BMI‐for‐age percentiles above the 97th may be imprecise and must be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

Results from this population‐based cross‐sectional study show a strong positive association between higher BMI‐for‐age and the prevalence of high BP in youth. Extremely obese youth are 10 times, moderately obese youth 4 times, and overweight youth twice as likely to have hypertension than their normal weight counterparts. Our results support the necessity to monitor overweight to obese children for high BP.

The setting of the present study is likely similar to other managed care settings, and the findings are likely generalizable to similar populations. The population at KPSC is also similar to the underlying population of Southern California regarding sociodemographic factors.11 The large sample size allowed well‐powered tests for interactions and a threshold determination by BMI‐for‐age percentile.

Few studies have evaluated the magnitude of the association between BMI and BP in pediatric populations.26, 27, 28, 29 Consistent with our results, a Swiss study found odds ratios of hypertension for overweight children of 2.7 (95% CI, 1.5–5.0) and 16.2 (95% CI, 9.1–28.9) for obese children.27 In a Texas school‐based study including 11‐ to 17‐year‐old students in 2003 to 2005, overweight youth had 1.39 (95% CI, 0.92–2.09) and obese youth had 4.26 (95% CI, 3.12–5.83) times the odds of having hypertension compared with normal weight youth.26 In earlier data in the same school‐based setting, the odds of hypertension was 3.49 (95% CI, 2.70–4.51) in obese children compared with their normal weight counterparts.28 Only one study29 examined a dose‐response relationship based on the degree of obesity. In that study,29 extremely obese youth (defined as ≥99th percentile of BMI‐for‐age) were 3 times as likely to have hypertension than moderately obese and 7 times as likely as normal weight youth, based on 3 visits with BP measurement to confirm a high BP. However, in that study,29 only frequencies but no odds ratios were provided, and the sample size of youth with ≥3 visits with BPs was very small (n=257).

Our results suggest that the risk of hypertension in extremely obese children is more than twice that of moderately obese children. This may have serious clinical implications for pediatric populations that have experienced a recent increase in the prevalence of extreme obesity.8, 30 However, long‐term studies are necessary to investigate the tracking of high BP from childhood into adulthood and the development of other cardiovascular risk factors for extremely obese compared with moderately obese youth. Health care providers could face another rise in the prevalence of hypertension in the coming years as a result of the shift toward extreme obesity in youth.

Several organizations recommend routine screening for high BP of asymptomatic youth during routine care visits; these organizations include the NHBPEP,12 the Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute,31 and the American Heart Association.32 Because studies are needed to assess whether screening for hypertension in youth reduces adverse health outcomes or delays the onset of hypertension in adults, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)9 has recently concluded that the evidence is lacking to recommend for or against routine screening for high BP in asymptomatic children—a conclusion that is discussed controversially.33 While measuring BP is inherently safe, there can be adverse outcomes from routine screening, including the time and resource costs of both families and health systems for making additional and perhaps unnecessary appointments when an elevated BP is found among low‐risk youth. For example, in our cohort, nearly 75,000 youth had at least 1 prehypertensive BP and nearly 40,000 children had at least 1 hypertensive BP, of which almost half were normal weight. Follow‐up at regular clinical visits such as annual health check visits can mitigate these costs but bear the potential to delay diagnosis and treatment of hypertension.

It was also concluded that the increase in hypertension in youth in the United States is largely driven by an increased BMI.9 As shown by our study and others, the prevalence of hypertension is much higher in obese than in normal weight youth. The results of our present study can inform future decisions between a general population‐wide screening and a targeted screening or closer follow‐up strategies in high‐risk populations to identify youth with high BP.

Scant knowledge is available about the optimal thresholds for BMI to predict high BP in children. In one study, the prevalence of prehypertension or hypertension in a Canadian pediatric population increased at the 85th percentile of BMI‐for‐age.34 Accordingly, we found a BMI‐for‐age at or above the 85th percentile that was able to predict high BP at the level of prehypertension or higher, but with a relatively low sensitivity and specificity. A BMI‐for‐age of 94th percentile was able to predict hypertension with an acceptable sensitivity and specificity. With little change in sensitivity and specificity, the threshold for hypertension can be rounded to the 95th percentile of BMI‐for‐age. If screening for high BP has to be limited to a high‐risk population, our results suggest that at a minimum requirement, children at or above the 95th percentile should be screened. However, it is well‐known that BP in children is variable. Due to our cross‐sectional study design and the lack of data on BP tracking over a longer period of time, our results have to be interpreted carefully and confirmed by longitudinal data.

The current thresholds for childhood overweight and obesity were developed empirically and are rather arbitrary.35, 36 Ideally, cut points describing overweight and obesity in youth would be based on the relationship between BMI and morbidity or mortality, but such data are only available for adults. Identifying cut points for overweight and obesity in children is more difficult since they manifest fewer conditions related to obesity at this age than do adults. Hence, adult cut points for overweight and obesity have been linked to BMI percentiles for youth in order to estimate the values of the 85th percentile for overweight and the 95th percentile for obesity.36, 37 Our data provide support for the validity of the current classification for childhood overweight and obesity with respect to identifying high BP.

Study Limitations

Several potential limitations are noted. First, the cross‐sectional study design precluded us from making causal inferences on the relationship between body weight and hypertension. However, a general association between obesity and hypertension is well established.38 Second, only results from single BP readings were available for this study electronically while repeated readings within one visit and the use of the average of these repeated visits are recommended.12 This may explain the high proportion of youth with high BP but is likely to reflect findings in other real‐world clinical settings. Third, we excluded only outpatient BP measurements that indicated the presence of fever because fever increases BP.39 We did not exclude medical visits related to any health conditions that may lead to slightly higher BP (eg, musculoskeletal pain) or limited BPs to those measured in healthy child visits, as has been done by others.40 Restricting the cohort to youth with at least 3 well‐child visits would have led to a substantial underestimation of the prevalence of high BP in adolescents because the frequency of healthy child visits decreases in adolescence. On the other hand, we cannot exclude that some BPs were elevated secondary to acute conditions. This, however, unlikely affected the results investigating the association between obesity and BP or the determination of a threshold to predict hypertension by BMI‐for‐age.

BP in routine clinical practice is usually measured by automated oscillometric devices while reference standards have been developed based on auscultatory methods.32 However, the discussion about its benefits and disadvantages are controversial.41 Generally, oscillometric devices tend to underestimate BP by approximately 2 mm Hg42 while auscultatory methods are prone to measurement error if used in non‐research settings.41 This potential underestimation, however, has been shown to be independent of body weight43 and relatively small in magnitude,42 and therefore not very likely to cause a significant underestimation of the prevalence of hypertension compared with potential errors arising from the use of auscultatory methods.41

Conclusions

Body weight in youth is strongly and positively associated with high BP. With >9% of extremely obese youth having hypertension and another 45% having 1 or 2 BP measurements in the hypertensive range, these youth are particularly at risk for hypertension and may need regular screening and follow‐up to identify and treat the condition. Our findings strongly support the need for recommendations to screen for hypertension in overweight and obese children at all outpatient medical visits. Additionally, our results also provide some validation for the current thresholds of pediatric overweight and obesity by predicting the prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension.

Sources of Funding and Conflicts of Interests

Research funding was provided to Dr Koebnick by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders (NIDDK, R21DK085395) and Kaiser Permanente Direct Community Benefit Funds. The authors report no conflicts of interest to disclose.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15:793–805. ©2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Obarzanek E, Wu CO, Cutler JA, et al. Prevalence and incidence of hypertension in adolescent girls. J Pediatr. 2010;157:461–467. 467 e461‐465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson M, Dana T, Bougatsos C, et al. Screening for Hypertension in Children and Adolescents to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease: Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD; 2013. [PubMed]

- 3. Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Ruan L, et al. Adult hypertension is associated with blood pressure variability in childhood in blacks and whites: the Bogalusa heart study. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Jonge LL, van Osch‐Gevers L, Willemsen SP, et al. Growth, obesity, and cardiac structures in early childhood: the generation R study. Hypertension. 2011;57:934–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Falkner B. Children and adolescents with obesity‐associated high blood pressure. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2008;2:267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flynn JT, Falkner BE. Obesity hypertension in adolescents: epidemiology, evaluation, and management. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13:323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koebnick C, Smith N, Coleman KJ, et al. Prevalence of extreme obesity in a multiethnic cohort of children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2010;157:26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thompson M, Dana T, Bougatsos C, et al. Screening for hypertension in children and adolescents to prevent cardiovascular disease. Pediatrics. 2013;131:490–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koebnick C, Langer‐Gould AM, Gould MK, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J. 2012;16:37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koebnick C, Coleman KJ, Black MH, et al. Cohort Profile: The KPSC Children's Health Study, a population‐based study of 920 000 children and adolescents in southern California. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:627–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents . The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 suppl 4th Report):555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American Association of Critical‐Care Nurses . American Association of Critical‐Care, Nurses Procedure Manual for Pediatric Acute and Critical Care, 1st edn. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents . The Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents, Revised version May 2005. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11. 2002;11:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization . Technical Report Series 894: Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. ISBN 92‐4‐120894‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden CL, et al. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index for age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1314–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith N, Coleman KJ, Lawrence JM, et al. Body weight and height data in electronic medical records of children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith N, Iyer RL, Langer‐Gould A, et al. Health plan administrative records versus birth certificate records: quality of race and ethnicity information in children. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bureau of the Census . Census 2000 Surname List. 2009. http://www.census.gov/genealogy/www/data/2000surnames/index.html. Accessed September 14, 2013.

- 22. Fiscella K, Fremont AM. Use of geocoding and surname analysis to estimate race and ethnicity. Health Serv Res. 2006;1:1482–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Word DL, Perkins RC. Building a Spanish Surname List for the 1990's ‐ A New Approach to an Old Problem. Technical Working paper No.13. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen W, Petitti DB, Enger S. Limitations and potential uses of census‐based data on ethnicity in a diverse community 4. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lambert J, Lipkovich I. Paper 231‐2008: A Macro for Getting More Out of Your ROC Curve. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26. McNiece KL, Poffenbarger TS, Turner JL, et al. Prevalence of hypertension and pre‐hypertension among adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007;150:640–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chiolero A, Cachat F, Burnier M, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in schoolchildren based on repeated measurements and association with overweight. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2209–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sorof JM, Lai D, Turner J, et al. Overweight, ethnicity, and the prevalence of hypertension in school‐aged children. Pediatrics. 2004;1:475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lo JC, Sinaiko A, Chandra M, et al. Prehypertension and hypertension in community‐based pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e415–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Flegal KM, Ogden CL, Yanovski JA, et al. High adiposity and high body mass index‐for‐age in US children and adolescents overall and by race‐ethnic group. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1020–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents of the National Heart L, Blood I . Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128(suppl 5):S213–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Samuels JA, Bell C, Flynn JT. Screening children for high blood pressure: where the US preventive services task force went wrong. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15:526–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tu W, Eckert GJ, Dimeglio LA, et al. Intensified effect of adiposity on blood pressure in overweight and obese children. Hypertension. 2011;58:818–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cole TJ. A chart to link child centiles of body mass index, weight and height. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:1194–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bellizzi MC, Dietz WH. Workshop on childhood obesity: summary of the discussion. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:173S–175S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dorresteijn JA, Visseren FL, Spiering W. Mechanisms linking obesity to hypertension. Obes Rev. 2012;13:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kiekkas P, Brokalaki H, Manolis E, et al. Fever and standard monitoring parameters of ICU patients: a descriptive study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2007;23:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hansen ML, Gunn PW, Kaelber DC. Underdiagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2007;298:874–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Myers MG. Why automated office blood pressure should now replace the mercury sphygmomanometer. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:478–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Landgraf J, Wishner SH, Kloner RA. Comparison of automated oscillometric versus auscultatory blood pressure measurement. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:386–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Umana E, Ahmed W, Fraley MA, Alpert MA. Comparison of oscillometric and intraarterial systolic and diastolic blood pressures in lean, overweight, and obese patients. Angiology. 2006;57:41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

High Blood Pressure in Overweight and Obese Youth: Implications for Screening

High Blood Pressure in Overweight and Obese Youth: Implications for Screening