Abstract

Paget disease of bone (PDB) is characterized by increased osteoclast activity and localized abnormal bone remodeling. PDB has a significant genetic component, with evidence of linkage to chromosomes 6p21.3 (PDB1) and 18q21-22 (PDB2) in some pedigrees. There is evidence of genetic heterogeneity, with other pedigrees showing negative linkage to these regions. TNFRSF11A, a gene that is essential for osteoclast formation and that encodes receptor activator of nuclear factor-κ B (RANK), has been mapped to the PDB2 region. TNFRSF11A mutations that segregate in pedigrees with either familial expansile osteolysis or familial PDB have been identified; however, linkage studies and mutation screening have excluded the involvement of RANK in the majority of patients with PDB. We have excluded linkage, both to PDB1 and to PDB2, in a large multigenerational pedigree with multiple family members affected by PDB. We have conducted a genomewide scan of this pedigree, followed by fine mapping and multipoint analysis in regions of interest. The peak two-point LOD scores from the genomewide scan were 2.75, at D7S507, and 1.76, at D18S70. Multipoint and haplotype analysis of markers flanking D7S507 did not support linkage to this region. Haplotype analysis of markers flanking D18S70 demonstrated a haplotype segregating with PDB in a large subpedigree. This subpedigree had a significantly lower age at diagnosis than the rest of the pedigree (51.2±8.5 vs. 64.2±9.7 years; P=.0012). Linkage analysis of this subpedigree demonstrated a peak two-point LOD score of 4.23, at marker D18S1390 (θ=0), and a peak multipoint LOD score of 4.71, at marker D18S70. Our data are consistent with genetic heterogeneity within the pedigree and indicate that 18q23 harbors a novel susceptibility gene for PDB.

Paget disease of bone (PDB [MIM 167250; MIM 602080), or osteitis deformans, is a skeletal disorder of unknown cause. This disease is characterized by excessive and abnormal bone remodeling due to increased bone resorption followed by disorganized bone formation (Krane 1986). PDB is the second-most-common metabolic bone disease (after osteoporosis), affecting ∼3% of the population at age >40 years (Siris 1998). It is more common in Western countries; conversely, it is extremely rare in China and most of sub-Saharan Africa (Rosenbaum and Hanson 1969; Detheridge et al. 1982). Reports of familial clustering, coupled with the demographics of PDB, indicate that genetic factors play an important role in its etiology. In 1972, an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance was proposed (McKusick 1972). Familial-aggregation studies indicate that subjects with a first-degree relative affected by PDB have a relative risk of 7 for developing the disease (Siris et al. 1991). A recent study from Spain, utilizing bone scans to identify subclinical disease, documented that 40% of patients had at least one affected first-degree relative (Morales-Piga et al. 1995).

Because of the late age at onset and the difficulty of ascertaining informative multiplex pedigrees, there has been a relative paucity of family studies of PDB. The PDB1 (MIM 167250) locus (HLA region, 6p21.3) was identified by Fotino et al. (1977) and was later supported by Tilyard et al. (1982); however, other linkage studies have failed to confirm these results (Breanndan Moore and Hoffman 1988). A recent report suggests that the HLA locus is unlikely to play a major role in the etiology of PDB (Laurin et al. 1999).

Familial expansile osteolysis (FEO [MIM 174810]) is a rare, autosomal dominant bone disorder sharing some characteristics with PDB. FEO has been described in a large Northern Irish pedigree (Osterberg et al. 1988; Wallace et al. 1989). The gene responsible for FEO has been linked to a region of chromosome 18q21.2-18q21.3 (Hughes et al. 1994). Positive linkage to this region has also been reported in some families with PDB (Cody et al. 1997; Haslam et al. 1998). This region is referred to as the “PDB2 locus” (MIM 602080). Cody et al. (1997) documented a maximum two-point LOD score of 3.40, at marker D18S42, in a large pedigree with PDB. One subject had PDB but did not carry the putative disease haplotype. The PDB region was bounded proximally by a recombination event at D18S39; however, the distal boundary was undefined, and it is possible that the region of linkage in this pedigree extends telomerically.

Approximately 1% of patients with PDB develop osteosarcoma (Hadjipavlou et al. 1992). Analysis of tumor-specific loss of constitutional heterozygosity in sporadic and Pagetic osteosarcomas has identified a putative tumor-suppressor locus within the PDB2 region (Nellissery et al. 1998).

TNFRSF11A (MIM 603499), a gene essential for osteoclast formation that encodes receptor activator of nuclear factor-κ B (RANK), has been mapped to the PDB2 region (Hughes et al. 2000). Recent studies have identified in exon 1 of TNFRSF11A an 18-bp insertion segregating with patients with FEO and a 27-bp insertion in exon 1 in families with PDB (Hughes et al. 2000). Affected individuals in a family with PDB studied by Hughes et al. (2000) did not express classical PDB, since subjects presented with bone pain or deformity in their teens and early 20s. Unlike the families with FEO, affected individuals have involvement of the axial skeleton, with lesions in the spine, pelvis, and mandible, as well as at sites associated with lesions in FEO. All affected patients have dental problems, and several have hearing impairment. These insertions affect the signal-peptide region of the RANK molecule and cause an increase in RANK-mediated nuclear factor-κ B signaling in vitro, consistent with the presence of an activating mutation (Hughes et al. 2000). Expression of recombinant forms of the mutant RANK proteins revealed perturbations in expression levels and the lack of normal cleavage of the signal peptide. A recent Australian study excluded TNFRSF11A exon 1 mutations in 82 patients with sporadic PDB and in 23 patients with familial PDB (Kormas et al. 2000).

Haslam et al. (1998) undertook linkage analysis in a number of multiplex pedigrees with PDB that were from diverse ethnic backgrounds, and they demonstrated exclusion of linkage with the PDB2 locus in some pedigrees, thus providing evidence of genetic heterogeneity. Recently, Laurin et al. (2001) performed genetic linkage analysis in 24 large French-Canadian families with PDB. The strongest evidence of linkage was on chromosome 5q35-qter, with a maximum LOD score of 8.58 under heterogeneity. In the 24 families, all patients from 8 families contained the same characteristic haplotype. The other 16 families were analyzed, resulting in the mapping of a second locus, at 5q31, with a maximum LOD score of 3.70.

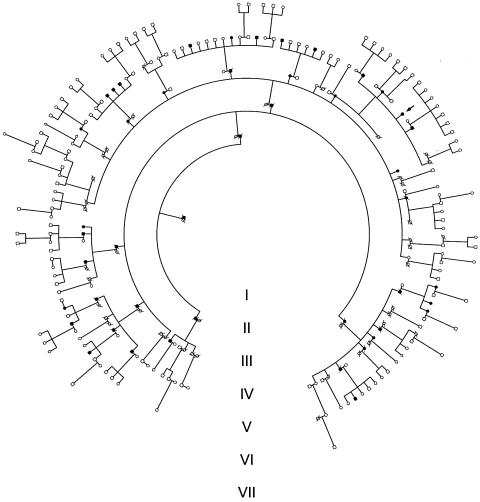

We have identified a large pedigree in which PDB appears to be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait (fig. 1). We have previously documented significantly negative LOD scores at the PDB1 and PDB2 loci in this pedigree (Good et al. 2001). We have proceeded with full-genome linkage analysis and have identified a novel susceptibility locus at 18q23, ∼20 Mb telomeric of TNFRSF11A (UCSC Human Genome Project Working Draft [“Golden Path”]).

Figure 1.

Pedigree structure. The shaded symbols indicate subjects affected by PDB, and the arrow indicates the proband.

Clinical characteristics of the pedigree are summarized in table 1 and are described elsewhere (Good et al. 2001). Previous diagnosis of PDB was confirmed by review of medical notes and bone scans. Study participants underwent measurement of the serum total alkaline phosphatase (SAP), with reference range 40–110 U/liter. Subjects with symptoms suggestive of PDB and/or with SAP >60 U/liter underwent bone scan and skeletal radiographs. The diagnosis of PDB was made on the basis of either the bone scan or radiological evidence. Asymptomatic subjects aged >60 years and with SAP levels ⩽60 U/liter were considered to be unaffected. Unaffected subjects aged <60 years were considered to be of unknown status, to allow for age-dependent penetrance (Ooi and Fraser 1997). It is possible that these diagnostic criteria may have misclassified some affected patients with inactive or localized disease.

Table 1.

Summary of Clinical Features of Living, Affected Individuals from the Pedigree

|

Current Treatment |

|||||

| Patienta | Age atDiagnosis(years) | Status | Duration | SAP(U/liter) | Distribution of Disease |

| III-11 | 76 | Newly diagnosed | … | 125 | Pelvis, right scapula |

| IV-10 | 59 | Nil to date | 24 years | 2,230 | Femur |

| IV-26 | 58 | Newly diagnosed | … | 673 | Extensive polyostotic disease |

| IV-28 | 55 | Pamidronate | 2 years | 353 | Extensive polyostotic disease |

| IV-33 | 58 | Alendronate | 1 year | 180 | Humerus |

| IV-37 | 58 | Alendronate | 2 mo | 673 | Both femora |

| IV-45 | 74 | Newly diagnosed | … | 77 | Skull |

| IV-46 | 62 | Alendronate | 6 mo | 1,697 | Skull, vertebrae, pelvis, right femur, humerus |

| IV-48 | 60 | Pamidronate | 26 years | 977 | Extensive polyostotic disease |

| IV-57 | 84 | Newly diagnosed | … | 63 | Left hip, left maxilla |

| V-05 | 53 | Newly diagnosed | … | 114 | L3 vertebra, right humeral head, left tibia |

| V-18 | 58 | Newly diagnosed | … | 273 | Cervical spine, L1 vertebra, sacrum, right pelvis, left femur |

| V-19 | 61 | Newly diagnosed | … | 147 | Scapula, sacrum, pelvis, tibia, right calcaneum |

| V-21 | 55 | Alendronate | 2 years | 50 | Skull, right femur, pelvis |

| V-37 | 59 | Newly diagnosed | … | 159 | Skull, left femur, left tibia, right ischium, left acetabulum |

| V-39 | 36 | Pamidronate | 6 years | 400 | Pelvis, left femur, right humerus |

| V-41 | 58 | Alendronate | 2 years | 61 | Skull, shoulder, pelvis, hips |

| V-43 | 62 | Newly diagnosed | … | 239 | Skull, left humerus, right tibia, left femur, right hemipelvis, vertebrae |

| V-48 | 49 | Newly diagnosed | … | 166 | Left himipelvis and sacrum |

| V-53 | 46 | Newly diagnosed | … | 100 | Left scapula |

| V-56 | 31 | Newly diagnosed | … | 86 | Distal left tibia |

| V-59 | 55 | Newly diagnosed | … | 98 | Right calcaneum |

| V-64 | 48 | Newly diagnosed | … | 105 | Skull, femora |

| V-73 | 50 | Alendronate | 1 year | 366 | Vertebrae, pelvis, left femur |

| V-74 | 60 | Alendronate | 2 years | 92 | Rib, shoulder, femora, tibiae |

| V-75 | 52 | Alendronate | 2 years | 93 | Femora, pelvis, base of skull |

| V-80 | 50 | Alendronate | 3 mo | 363 | Pelvis, base of skull |

| V-102 | 69 | Nil to date | … | 246 | Left tibia, left shoulder, left femur |

| V-104 | 70 | Newly diagnosed | … | 126 | Right femur |

| V-108 | 53 | Newly diagnosed | … | 106 | Right tibia, skull |

Patient identity numbers are read counterclockwise from the pedigree diagram (fig.1).

DNA was extracted from blood samples by the salting-out method (Miller et al. 1988). Subjects were initially genotyped using a genetic map consisting of 400 autosomal markers with anticipated mean ± SD heterozygosity of 0.74±0.11, at the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF) (Ewen et al. 2000). The mean ± SD sex-averaged distance between adjacent markers is 8.6±6.5 cM (range 0–34 cM). The genomewide scan was performed on 61 individuals from the pedigree, 27 of whom were affected with PDB.

Genetic linkage analysis was performed using FASTLINK v4.1 (Cottingham et al. 1993; Schäffer et al. 1994). Relationships between sibs were verified using RELATIVE (Göring and Ott 1997). On the basis of the pedigree data, we assumed an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with disease penetrance set at 90%. We assumed a trait-allele frequency of 0.01 and a phenocopy rate of 2.3%, which yield a population prevalence of 4% and a sibling recurrence risk of 0.225 (λs=5.6). These are consistent with Australian epidemiological data for PDB (Gardner et al. 1978). Simple counting estimates have been used to calculate allelic frequencies in the pedigree, to avoid errors. Differences in age at diagnosis were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Wilcoxon 1945).

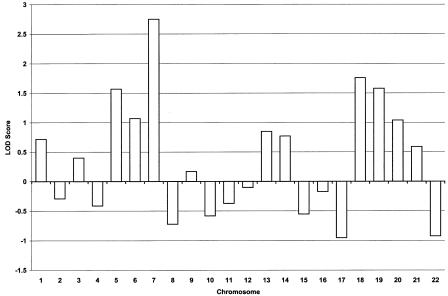

Peak two-point LOD scores from the genomewide scan are presented in figure 2. Under the criteria of Rao and Province (2000), a P value <.0023, which corresponds to a LOD score ⩾1.75, is considered to be highly suggestive evidence of linkage (Rao and Province 2000). Suggestive linkage was indicated on chromosomes 7p21 and 18q23, with peak two-point LOD scores of 2.75 (θ=0.1), at D7S507, and 1.76 (θ=0.1), at D18S70. To ensure that all markers were genotyped for the same number of individuals, missing genotypes were completed, and further fine mapping was performed, by manual genotyping in our laboratory, as described elsewhere (Good et al. 2001). Fine mapping in the chromosomes 7 and 18 regions was undertaken for 88 pedigree members, 30 of whom are affected by PDB. Genotyping for genomewide-scan markers in the region of interest was repeated manually, to confirm the genomewide-scan results for this marker.

Figure 2.

Summary of two-point LOD scores, by chromosome, generated by genomewide scan

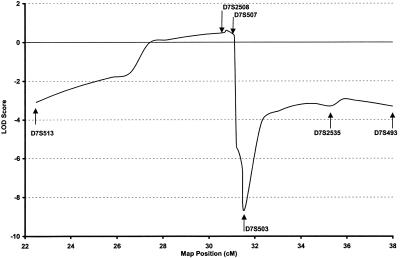

The multipoint LOD scores generated by fine mapping in the region of positive linkage on chromosome 7 are shown in figure 3, with peak multipoint LOD score of 0.62 at marker D7S508. These results failed to support evidence of linkage in the region flanking marker D7S507. Haplotype analysis of genotyped individuals by use of markers spanning 15 cM flanking D7S507 showed no evidence of a disease haplotype segregating in the pedigree. We concluded that, taken in conjunction with the multipoint analysis, this region was not linked to PDB in this pedigree.

Figure 3.

Multipoint LOD scores for chromosome 7 markers flanking D7S507, analyzed for entire pedigree. Positions given are sex-averaged distances and are from the Genetics Location Database.

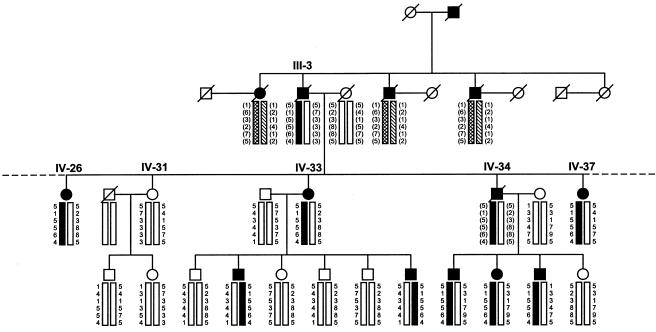

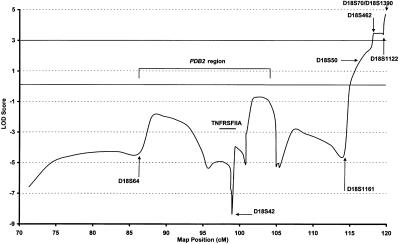

Haplotype analysis of markers flanking the region of interest on chromosome 18q23 was conducted using six markers spanning a 9-cM region telomeric to and including D18S1161 (the Genetics Location Database). For deceased individuals, haplotypes were inferred. A distinct haplotype was noted to segregate with PDB in a large subpedigree (descendants of subject III-3; fig. 4). This largest branch of the family consists of 54 genotyped study participants, including 17 living subjects affected with PDB; in addition, the genotypes of 4 deceased affected subjects can be inferred. This subpedigree has an earlier age at onset of PDB than the remainder of the pedigree; mean ± SD age at diagnosis was 51.2±8.5 years versus 64.2±9.7 years (P=.0012). This subpedigree demonstrated a peak two-point LOD score of 4.23 at θ=0, at marker D18S1390 (table 2). Multipoint linkage analysis of the subpedigree yielded a peak LOD score of 4.71, at marker D18S70 (fig. 5). The multipoint LOD score was significantly negative at the PDB2 locus in this subpedigree (fig. 5). At D7S507, the maximum LOD score for this subpedigree was −1.35 at θ=0. The linked haplotype at 18q23 (illustrated in fig. 4) is present in 18 of the 21 affected subjects in the subpedigree. Nine subjects aged <60 years (mean age 50.4±7.4) have the at-risk haplotype but currently show no radiological evidence of PDB. The mean ± SD SAP level of these subjects was 88±14.2 U/liter. There are three apparent phenocopies in the subpedigree. One of these subjects (IV-22) is deceased and was diagnosed as having PDB in the cervical spine, at the age of 83 years, on the basis of plain radiographs. These radiographs were not available for our review. Her four offspring, aged 63–71 years, are, at present, unaffected by PDB. The other two apparent phenocopies were diagnosed at the ages of 58 (V-41) and 62 (V-43) years. Their mother and two affected siblings carry the at-risk haplotype. Their father was deceased at the time of the clinical study. He had had symptoms suggestive of PDB but had not undergone biochemical or radiological evaluation and, for the linkage analysis, was considered to be of unknown status.

Figure 4.

Haplotype analysis of representative sample of subpedigree, for chromosome 18q23. This subpedigree, which shows significant linkage to 18q23, is descended from subject III-3. The haplotype that segregates with PDB in the subpedigree is indicated by the black bar; haplotypes in parentheses are inferred. Subject III-3 had 13 offspring, but, in the interests of space and clarity, only 5 are shown here; subject IV-34 had 11 offspring, but, in the interests of space and clarity, only 4 are shown here. The putative affected haplotype, with the exception of three apparent phenocopies, is shared by all affected descendants of subject III-3.

Table 2.

Two-Point LOD Scores for Chromosomal Region 18q, for the Subpedigree[Note]

|

LOD Score at θ = |

||||||||

| Marker | Positiona(cM) | .00 | .01 | .05 | .10 | .20 | .30 | .40 |

| D18S474 | 71.3 | −6.62 | −5.75 | −4.05 | −2.91 | −1.44 | −.59 | −.14 |

| PDB2 region: | ||||||||

| D18S64 | 86.37 | −1.27 | −1.09 | −.70 | −.46 | −.19 | −.04 | .00 |

| D18S60 | 94.83 | −4.83 | −3.83 | −2.34 | −1.46 | −.59 | −.19 | −.04 |

| D18S68 | 98.73 | −3.78 | −3.08 | −1.99 | −1.25 | −.46 | −.13 | −.02 |

| D18S42 | 98.99 | −2.82 | −2.52 | −1.87 | −1.48 | −1.01 | −.62 | −.29 |

| D18S483 | 100.82 | −2.64 | −2.28 | −1.41 | −.84 | −.33 | −.15 | −.08 |

| D18S878 | 100.93 | −1.07 | −.91 | −.5 | −.22 | .04 | .11 | .04 |

| D18S466 | 104.83 | −2.67 | −2.30 | −1.52 | −.95 | −.31 | −.06 | .00 |

| D18S61 | 105.43 | −1.17 | −1.03 | −.85 | −.76 | −.42 | −.15 | −.03 |

| D18S1161 | 114.17 | −3.24 | −2.98 | −2.02 | −1.22 | −.41 | −.09 | −.01 |

| D18S50 | 117.91 | 1.74 | 1.73 | 1.67 | 1.55 | 1.22 | .77 | .25 |

| D18S462 | 119.29 | 2.70 | 2.73 | 2.74 | 2.60 | 2.07 | 1.31 | .45 |

| D18S1122 | 119.55 | 1.20 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.15 | .90 | .54 | .14 |

| D18S70 | 119.84 | 4.01 | 3.99 | 3.83 | 3.50 | 2.63 | 1.62 | .59 |

| D18S1390 | 119.84 | 4.23 | 4.16 | 3.85 | 3.42 | 2.46 | 1.43 | .46 |

Note.— The subpedigree is composed of descendants of subject III-3 (fig. 1). The subpedigree is a large family, in which the age at onset of PDB is earlier than that in the rest of the pedigree.

Sex-averaged distances from the Genetics Location Database.

Figure 5.

Multipoint LOD scores for chromosome 18 markers, in subpedigree. Positions given are sex-averaged distances and are from the Genetics Location Database. The PDB2 region is indicated.

Total genomic DNA of subjects from the pedigree was sequenced to assess for mutations in exon 1 of TNFRSF11A. Mutations in exon 1 were analyzed by sequencing of PCR products by use of Big Dye Terminator (Applied Biosystems). PCR conditions were as described by Hughes et al. (2000) and incorporated the following primer pair: forward, 5′-TGGGTACCACCTGGCTGGCAC-3′; and reverse, 5′-AAGGCGGAGGAGCCAGGATGC-3′. Gel separation was performed by the AGRF, on an ABI 377. Affected subjects from the pedigree, including four from the subpedigree with an earlier age at onset (descendants of subject III-3; fig. 4), were examined. Unaffected subjects from this subpedigree were also examined. No mutations were identified in the coding sequence in either affected or unaffected subjects. In three of the affected subjects, two previously reported nonfunctional polymorphisms were noted: −1 G/A close to the start position of transcription and +30 T/C within the 5′ UTR, nine bases before the initiation codon (Hughes et al. 2000).

Analysis of the kindred, excluding the subpedigree in which PDB maps to 18q23, failed to identify additional significant regions of linkage. The following secondary peak LOD scores were obtained from this analysis: 1.34, at D21S266, and 1.66, at D9S1776.

Our data raise the possibility of genetic heterogeneity within the pedigree, as has elsewhere been demonstrated for pedigrees with type 2 diabetes and maturity-onset diabetes of the young (Stoffel et al. 1992; Yamagata et al. 1996). It is possible that the susceptibility-gene mutation that was localized to 18q23 may modulate the age at onset of the PDB phenotype in this pedigree. Chromosome 18q23 has not previously been implicated in the etiology of PDB. The negative linkage data at 18q21.3 and the absence of mutations in exon 1 of TNFRSF11A support exclusion of this gene as causative in this pedigree.

A number of candidate genes are located in the vicinity of the maximum LOD score. One of these candidates, NFATc1, is a member of the NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) family of genes. The NFAT family of transcription factors play a pivotal role in the transcription of many genes critical for the immune response, including the genes for cytokines IL2, IL4 granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and tumor-necrosis factor-α (Rao et al. 1997). Furthermore, 1,25 (OH)2D3 repression of IL2 and GM-CSF transcription has been shown to be affected by competition between the vitamin D receptor and NFATc2 (Alroy et al. 1995; Towers et al. 1999), suggesting a possible pathway by which NFATc1 mutations could be implicated in PDB. NFAT transcription factors have also been shown to regulate osteoclast-specific expression of the calcitonin receptor and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase genes (Galson et al. 2000).

PDB is a complex, genetically heterogeneous disorder that may result from the joint action of and interaction between genetic and environmental factors. We have ascertained a large pedigree with familial PDB. We have excluded linkage with the PDB1 and PDB2 regions, have excluded mutations in exon 1 of TNFRSF11A, and have identified a novel susceptibility locus for PDB, at chromosome 18q23, in a large subpedigree. Several candidate genes have been identified in the region, and we plan to continue to use fine mapping, haplotype analysis, and sequence analysis to identify the nature of the susceptibility gene. The identification of genetic markers for PDB is fundamental for understanding the cause of the disease; for identifying, at a preclinical stage, subjects at risk; and for the development of more-effective preventive and therapeutic strategies for the management of the condition.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the family for their participation in the research program. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Robin J. Leach (Department of Cellular and Structural Biology, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio) and Prof. F. R. Singer (John Wayne Cancer Institute at St. John’s Hospital and Health Center, Santa Monica, CA), who provided DNA and clinical information for an affected pedigree member. We are also grateful to Dr. Marina Kennerson (ANZAC Research Institute, University of Sydney, Concord, Australia) for assistance with TNFRSF11A sequencing. This research was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Project Grant, The Princess Alexandra Hospital Research and Development Foundation, The Paget Foundation Annual Research Award, the Arthritis Foundation of Australia Heidenreich Paget’s Disease Grant, the Roy Percy Blath Bequest, and the Merck Genome Research Institute. The genomewide scan was performed at the AGRF.

Electronic-Database Information

Accession numbers and URLs for data in this report are as follows:

- Genetics Location Database, The, http://cedar.genetics.soton.ac.uk/public_html/ldb.html

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for PDB/PDB1 [MIM 167250], PDB2 [MIM 602080], FEO [MIM 174810], and TNFRSF11A [MIM 603499])

- UCSC Human Genome Project Working Draft (“Golden Path”), http://genome.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hgTracks.html

References

- Alroy I, Towers TL, Freedman LP (1995) Transcriptional repression of the interleukin-2 gene by vitamin D3: direct inhibition of NFATp/AP-1 complex formation by a nuclear hormone receptor. Mol Cell Biol 15:5789–5799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breanndan Moore S, Hoffman DL (1988) Absence of HLA linkage in a family with osteitis deformans (Paget's disease of bone). Tissue Antigens 31:69–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody JD, Singer FR, Roodman GD, Otterund B, Lewis TB, Leppert M, Leach RJ (1997) Genetic linkage of Paget disease of the bone to chromosome 18q. Am J Hum Genet 61:1117–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottingham RW Jr, Idury RM, Schäffer AA (1993) Faster sequential genetic linkage computations. Am J Hum Genet 53:252–263 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detheridge FM, Guyer PB, Barker DJ (1982) European distribution of Paget's disease of bone. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 285:1005–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewen KR, Bahlo M, Treloar SA, Levinson DF, Mowry B, Barlow JW, Foote SJ (2000) Identification and analysis of error types in high-throughput genotyping. Am J Hum Genet 67:727–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotino M, Haymovits A, Falk CT (1977) Evidence for linkage between HLA and Paget's disease. Transplant Proc 9:1867–1868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galson DL, Peng L, Li X, Laplace C, Buchler M, Goldring SR, Wagner FP, Matsuo K (2000) Osteoclast-specific expression of the calcitonin receptor and TRAP genes is regulated by NFAT transcription factors. J Bone Miner Res Suppl 15:S219 [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MJ, Guyer PB, Barker DJ (1978) Paget's disease of bone among British migrants to Australia. Br Med J 2:1436–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good D, Busfield F, Duffy D, Lovelock PK, Kesting JB, Cameron DP, Shaw JTE (2001) Familial Paget's disease of bone: nonlinkage to the PDB1 and PDB2 loci on chromosomes 6p and 18q in a large pedigree. J Bone Miner Res 16:33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göring HH, Ott J (1997) Relationship estimation in affected sib pair analysis of late-onset diseases. Eur J Hum Genet 5:69–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjipavlou A, Lander P, Srolovitz H, Enker IP (1992) Malignant transformation in Paget disease of bone. Cancer 70:2802–2808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam SI, Van Hul W, Morales-Piga A, Balemans W, San-Millan JL, Nakatsuka K, Willems P, Haites NE, Ralston SH (1998) Paget's disease of bone: evidence for a susceptibility locus on chromosome 18q and for genetic heterogeneity. J Bone Miner Res 13:911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AE, Ralston SH, Marken J, Bell C, MacPherson H, Wallace RG, van Hul W, Whyte MP, Nakatsuka K, Hovy L, Anderson DM (2000) Mutations in TNFRSF11A, affecting the signal peptide of RANK, cause familial expansile osteolysis. Nat Genet 24:45–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AE, Shearman AM, Weber JL, Barr RJ, Wallace RG, Osterberg PH, Nevin NC, Mollan RA (1994) Genetic linkage of familial expansile osteolysis to chromosome 18q. Hum Mol Genet 3:359–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kormas N, Kennerson M, Hooper A, Vale M, Nicholson G (2000) Does the TNFRSFIIA insertion mutation occur in familial Paget's disease of bone in Australia? Bone Suppl 27:25S [Google Scholar]

- Krane S (1986) Paget's disease of bone. Calcif Tissue Int 38:309–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurin N, Brown J, Duchesne A, Brousseau C, Huot D, Lacourciere Y, Drapeau G, Verreault J, Raymond V, Morissette J (1999) Genetic heterogeneity of Paget's disease of bone: exclusion of linkage to the PDB1 and PDB2 loci in French-Canadian pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet Suppl 65:A258 [Google Scholar]

- Laurin N, Brown JP, Lemainque A, Duchesne A, Huot D, Lacourciere Y, Drapeau G, Verreault J, Raymond V, Morissette J (2001) Paget disease of bone: mapping of two loci at 5q35-qter and 5q31. Am J Hum Genet 69:528–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKusick VA (1972) Heritable disorders of connective tissue. CV Mosby, St Louis, pp 718–737 [Google Scholar]

- Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF (1988) A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res 16:1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Piga AA, Rey-Rey JS, Corres-Gonzalez J, Garcia-Sagredo JM, Lopez-Abente G (1995) Frequency and characteristics of familial aggregation of Paget's disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res 10:663–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellissery MJ, Padalecki SS, Brkanac Z, Singer FR, Roodman GD, Unni KK, Leach RJ, Hansen MF (1998) Evidence for a novel osteosarcoma tumor-suppressor gene in the chromosome 18 region genetically linked with Paget disease of bone. Am J Hum Genet 63:817–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi CG, Fraser WD (1997) Paget's disease of bone. Postgrad Med J 73:69–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterberg PH, Wallace RG, Adams DA, Crone RS, Dickson GR, Kanis JA, Mollan RA, Nevin NC, Sloan J, Toner PG (1988) Familial expansile osteolysis: a new dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Br 70:255–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao A, Luo C, Hogan PG (1997) Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu Rev Immunol 15:707–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao DC, Province MA (2000) The future of path analysis, segregation analysis, and combined models for genetic dissection of complex traits. Hum Hered 50:34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum HD, Hanson DJ (1969) Geographic variation in the prevalence of Paget's disease of bone. Radiology 92:959–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäffer AA, Gupta SK, Shriram K, Cottingham RW Jr (1994) Avoiding recomputation in linkage analysis. Hum Hered 44:225–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siris ES (1998) Paget's disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res 13:1061–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siris ES, Ottman R, Flaster E, Kelsey JL (1991) Familial aggregation of Paget's disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res 6:495–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel M, Patel P, Lo YM, Hattersley AT, Lucassen AM, Page R, Bell JI, Bell GI, Turner RC, Wainscoat JS (1992) Missense glucokinase mutation in maturity-onset diabetes of the young and mutation screening in late-onset diabetes. Nat Genet 2:153–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilyard MW, Gardner RJ, Milligan L, Cleary TA, Stewart RD (1982) A probable linkage between familial Paget's disease and the HLA loci. Aust NZ J Med 12:498–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towers TL, Staeva TP, Freedman LP (1999) A two-hit mechanism for vitamin D3-mediated transcriptional repression of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene: vitamin D receptor competes for DNA binding with NFAT1 and stabilizes c-Jun. Mol Cell Biol 19:4191–4199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RG, Barr RJ, Osterberg PH, Mollan RA (1989) Familial expansile osteolysis. Clin Orthop 248:265–277 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcoxon F (1945) Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometrics 1:80–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata K, Furuta H, Oda N, Kaisaki PJ, Menzel S, Cox NJ, Fajans SS, Signorini S, Stoffel M, Bell GI (1996) Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1). Nature 384:458–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]