Abstract

Terminal illness affects the entire family, both the one with the illness and their loved ones. These loved ones must deal not only with the loss but with the challenges of managing daily care. The purpose of the systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature was to identify and explore depression and related interventions for caregivers of hospice patients. While the prevalence of depression reported in the identified studies of hospice caregivers ranges from 26–57%, few interventions specific to this population have been tested and the research methods have been only moderately rigorous.

Keywords: hospice, caregiving, depression

The work of Dame Cicely Saunders at St Joseph’s Hospice in Hackney, East London proved to be instrumental in re-defining care for the dying and creating a philosophy of care that later became the foundation for the modern hospice movement (Clark, Smith, Wright, Winslow, & Hughes, 2005). Her experience as a nurse, physician, and social worker provided the foundation for the development of two of Saunders’ most important principles which serve as the backbone of hospice care. First was the importance of focusing on the management of pain; second, was her acknowledgement that patients and their loved ones suffer at the end of life and, thus, both require care. These principles are paramount today as hospice promotes the management of total pain (comprised of physical, mental, social, existential and spiritual distress) and considers both the patient and family as the unit of care. In fact, Saunders claimed that “mental distress may be perhaps the most intractable pain of all” (Saunders, 1963, p. 64).

Terminal illness affects not only the individual with the diagnosis but also the loved ones who surround him or her and, most of all, the caregiver (family members and/or friends) who manages daily care needs. Research has found that all aspects of a caregiver’s life are affected including physical, emotional, and social well-being (Wilder, Parker Oliver, Demiris, & Washington, 2008). Caregivers have been found to experience anxiety, depression, physical symptoms, and strain in marital relationships (McMillan, 2005). Caregivers of dying people have been identified as being at greater risk for depression, health problems and increased mortality rates than the general population (Gough & Hudson, 2009; McMillan, 2006). It therefore seems appropriate that hospices should use tools for the routine screening of common types of mental distress.

Among the dimensions that comprise total pain at the end of life, depression remains under-diagnosed in hospice care (Ani, Bazargan, & Hindman, 2008; Block, 2000). Social workers -- members of the hospice team -- are trained in family psychosocial assessment and are the key to identifying caregivers at risk (Gladjchen, 2011). Likewise, social workers provide numerous interventions for individuals suffering from emotional or mental distress, including depression. Research, while informing the presence of depression and other mental and emotional pain, has not produced adequate evidence about the effectiveness of interventions, particularly related to hospice family caregivers. Most research has been descriptive and evaluative with only a limited number of clinical trials having been conducted (McMillan, 2005). Similarly, the use of specific standardized instruments for assessment and screening of hospice caregivers has been limited, and hospice providers standardly use no specific instrument. In fact, documentation of any systematic assessment of caregivers in hospice has been found to be sparse (Hermann & Looney, 2001; McMillan, Small, & Haley, 2011).

The purpose of this systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature was to identify and explore depression and related interventions for caregivers of hospice patients. The review sought to answer three research questions. First, what standardized measures or instruments have been used to assess depression in caregivers of hospice patients? Second, what is the known prevalence of depression in hospice caregivers? And, finally, which interventions have been shown to be effective in treating depression in hospice caregivers?

Methods

A systematic review of the published peer-reviewed literature was undertaken to assess the evidence related to the prevalence and treatment of depression of caregivers in the hospice setting. CINAHL, Medline, PsycINFO, and Scopus were searched for studies published between January 1, 1970 and August 24, 2012. Key phrases in the search included “hospice caregiver depression”, “caregiver depression intervention”, “caregiver depression measurement”, “caregiver depression frequency”, “caregiver depression assessment”, “caregiver depression epidemiology”, “hospice depression intervention”, “depression hospice systematic reviews”, “hospice caregivers’ ‘quality of life’”, “depression/ [therapy] caregivers”, “hospice care caregivers’ depression”. Studies were included if they were published in English in peer-reviewed journals, reported empirical data, and were specific to caregivers hospice patients in the United States. Studies on bereavement were only included when there was a measure of pre-loss depression. Also excluded were studies of caregivers who were in general palliative care programs, rather than hospice-specific programs. The search was limited to U.S. hospice caregivers because the definition of an enrolled “hospice patient” is uniquely different in the United States. In the United States, reimbursement limitations are required for hospice care (such as life expectancy of six months) thereby resulting in a significant number of US hospice patients receiving homecare rather than care in a “hospice inpatient facility”. Caring for an individual at home often adds additional stress to the hospice caregiver (D. Lau et al., 2012; D. T. Lau et al., 2010). Two members of the research team reviewed the abstracts and papers and jointly agreed on the final set of articles for the sample.

Once a final set of articles was identified by applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria, duplicates were removed, and data were extracted from each article using a standardized form. The extraction process identified the authors, sample size, research questions, study design, and findings. Data collected from the standardized form were entered into an Excel spreadsheet for analysis.

After identifying the final sample of published studies and extracting the data, each article was scored using the techniques suggested by Gysles and Higginson (2007) for systematic reviews in palliative medicine. As suggested, each study received a score to reflect its methodological rigor. A standardized scoring form was developed to promote reliability in scoring across studies (see Tables 1 and 2). The quantitative articles were scored using a format modified from Gysles and Higginson (2007) that recognized differences between observational and experimental research. Higher scores represented higher scientific rigor in data collection, analysis, and reporting using this technique. Scores ranged from 0–22 depending on the presence of elements influencing the rigor. Articles with scores of 0–7 were considered weak evidence, scores of 8–15 moderate, and scores of 16–22 reflected strong evidence (see Table 1).

Table 1. Method to score quantitative articles.

| 1. Aims/outcome (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Defined at outset | 2 |

| b. Implied in paper | 1 |

| c. Unclear | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | |

| 2. Sample formation (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Random | 2 |

| b. Quasi-random; sequential series in given setting or total available | 1 |

| c. Selected, historical, other, insufficient information | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | |

| 3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Explicitly described | 2 |

| b. Implied by patient characteristics, setting | 1 |

| c. Unclear | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | |

| 4. Subjects described (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Full information | 2 |

| b. Partial information | 1 |

| c. No information | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | |

| 5. Power of study calculated (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Yes | 2 |

| b. No | 0 |

| c. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | |

| 6. Outcome measures (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Objective | 2 |

| b. Subjective | 1 |

| c. Not explicit | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | |

| 7. Follow-up* (observational and experimental) | |

| a. >80% of subjects available for follow up | 2 |

| b. 70–80% of subjects available for follow up | 1 |

| c. < 70% of subjects available for follow up | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | |

| 8. Analysis (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Intention to treat/including all available data | 2 |

| b. Excluding drop-outs but evidence of bias adjusted or no bias evident | 1 |

| c. Excluding drop-outs and no attention to bias or imputing results | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | |

| 9. Baseline differences between groups (experimental only) | |

| a. None or adjusted | 2 |

| b. Differences unadjusted | 1 |

| c. No information | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | 0 |

| 10. Unit of allocation to intervention (experimental only) | |

| a. Appropriate | 2 |

| b. Nearly | 1 |

| c. Inappropriate or no control group | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | 0 |

| 11. Randomization/method of allocation of subjects (experimental only) | |

| a. Random | 2 |

| b. Method not explicit | 1 |

| c. Before exclusion of drop-outs or non-randomized | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | 0 |

| Total score | |

Follow up modified from original to reflect time frames identified in the study and percentages changed to reflect high attrition found in hospice studies

Table 2. Method to score Qualitative articles.

| 1. Is there a clear connection to an existing body of knowledge/theoretical framework? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 2. Are research methods appropriate to the question being asked? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 3. Is the description of the context for the study clear and sufficiently detailed? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 4. Is the description of the method clear and sufficiently detailed to be replicated? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 5. Is there an adequate description of the sampling strategy? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 6. Is the method of data analysis appropriate and justified? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 7. Are procedures for data analysis clearly described and in sufficient detail? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 8. Is there evidence that the data analysis involved more than one researcher? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 9. Are the participants adequately described? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 10. Are the findings presented in an accessible and easy to follow manner? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 11. Is sufficient original evidence provided to support the relationship between interpretation and evidence? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| Total Score | |

Likewise, the methodological rigor for qualitative research articles was assessed using a standardized scoring form modified from the work of Greenwood and colleagues (2009). There is debate regarding the feasibility of quality assessment in qualitative research, and there is no gold standard scoring criteria for qualitative research. Greenwood’s model was selected because of its inclusion of relevant elements from several qualitative assessment frameworks and the ease of assessment and scoring generated from this approach. Similar to the quantitative scoring, a higher score reflects a higher degree of methodological rigor in data collection, analysis, and reporting (see Table 2). Articles were scored on a 0–11 scale. In general, the more transparent the data collection and analysis, or the better detailed the procedures, the higher the score, as rigor in qualitative studies is often based on the trustworthiness of data (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003).

Two members of the research team independently reviewed articles (AG, MM) and graded all evidence using the above approach. All inconsistencies were reviewed and a discussion led to consensus on final scores. The final scores were reviewed by the first author (DPO) and no changes were made.

Results

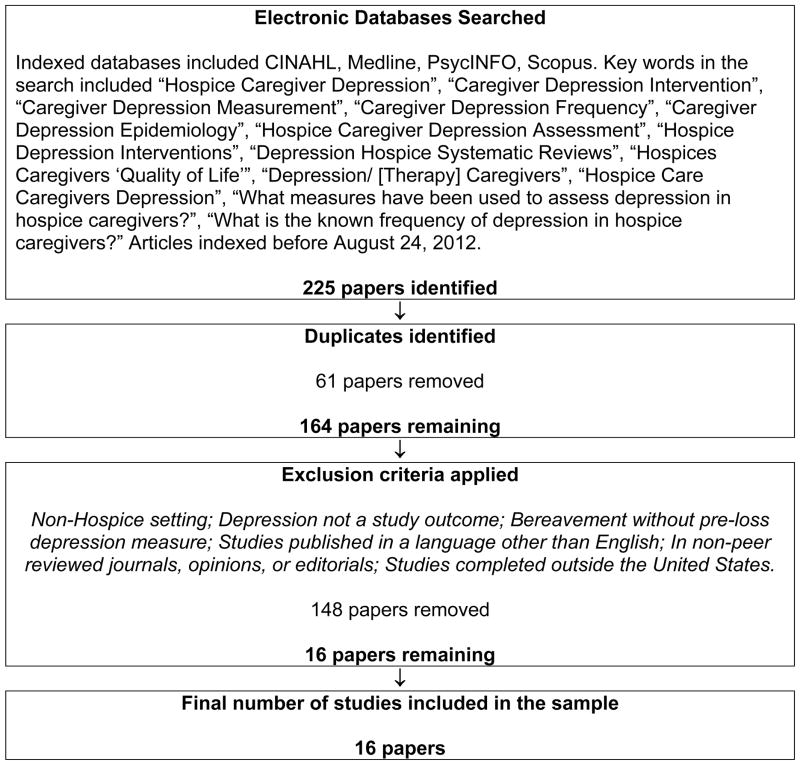

The initial search strategy identified 225 published articles that met the criteria outlined. After a review of the abstracts and elimination of duplicates from the combined databases, a list of 164 studies was generated. Further, after application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 16 unduplicated, peer-reviewed, empirically-based caregiver depression studies in hospice care published before August 24, 2012 were assembled; these studies comprise the final sample analyzed in this review. Figure 1 is a flow diagram of the sampling process.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Sample

The 16 studies were published in 10 unique journals, with no journal publishing more than three of the studies; indicating limited journal bias. The studies involved 44 different authors (including co-authors), however three teams of researchers published 11 of the 16 papers. Funding was acknowledged in 12 studies and included the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), numerous foundations, and several university funding sources. The mean sample size of all studies was 146, although there was a large variance with a range of 6 to 702. The majority (9) of these articles were a sub-study, based on data from larger studies. Four studies involved an initial assessment of depression in hospice caregivers; however, the focus of these studies were during the bereavement phase following the hospice experience. Table 3 identifies and summarizes the articles in the sample.

Table 3.

Summary of the Evidence

| Article | Purpose/sample size | Funding | Prevalence of Depression | Measure | Findings | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradley et al. (2004) | To assess the impact of length of hospice enrollment on caregiver major depressive disorder N=174 |

Foundation and NIMH | 25.9% | SCID | Baseline prevalence was 25.9% and follow-up was 11.5%. Caregivers of patients enrolled in hospice within 3 or fewer days of their death were more likely to be depressed follow-up than those who enrolled earlier. | 11 |

| Buck & McMillan (2008) | To identify the spiritual needs of the informal caregivers of cancer patients using a standardized instrument and explore the relationships among the patient’s global symptom distress, caregivers unmet spiritual needs, and depressive symptomatology in the caregiver N=110 |

Not reported | Not reported | CES-D | The caregivers’ depression score was related to unmet needs. As the number of unmet needs increased, so did the CES-D score. | 11 |

| Burton et al. (2008) | To assess the extent to which stressors, appraisals, social support, and well-being while caregiving predict well-being during bereavement N=50 |

University funded | Not reported | CES-D | Being non-White, having fewer months caregiving, and having lower levels of social resources were significant predictors of depression. Pre-loss depression was not very highly correlated with post- loss depression. | 11 |

| Chentsova- Dutton et al. (2000) | To examine emotional and physical adjustment and social and occupational functioning of hospice caregivers; also compares the effects of caregiving on spouses and adult children and male and female caregivers of hospice patients N=181 |

Foundation | Feeling lonely 19% Feeling blue 34% Sleep problems 22% Suicidal thoughts 14% |

HPRSD BDI |

Caregivers had significantly higher levels of depression than controls. Caregiver spouses were more depressed than adult children. Women had higher levels of depression than men. | 10 |

| Cherlin et al. (2007) | To assess the degree to which bereavement services are used by surviving family caregivers of hospice patients, identify the predictors of service use and potential barriers to the use of hospice bereavement services N=161 |

Foundation and NIMH | 26.1 % at baseline | SCID | Among depressed caregivers at baseline, 19.6% did not use services when they became bereaved. Many caregivers with baseline depression believed that bereavement services would not be beneficial to them. | 7 |

| Fenix et al. (2006) | To examine the association between religiousness and depression among bereaved hospice caregivers N=175 |

Foundation, NIMH, and NCI | Not reported | SCID | Although pre-bereavement depression measured it was not reported- no findings reported were applicable to this review. | 9 Quant 8 Qual |

| Haley, LaMonde, Han, Burton, & Schonwetter (2003) | To examine the applicability of a stress process model for spousal caregivers of the terminally ill N=80 |

University | Mean CES-D score = 17.73a | CES-D | Wives and those with behavioral problems, poor health, and/or negative social interactions had higher depression levels. | 12 |

| Haley, LaMonde, Han, Narramore, & Schonwetter (2001) | 1) To assess the impact of caregiving stress on psychological and health functioning in spousal caregivers 2) To compare the caregiving stressors faced by spousal caregivers of patients with lung cancer versus dementia 3) To assess whether psychological and physical health functioning differs in spousal caregivers of hospice patients with dementia versus lung cancer N=120 |

University | 50% for both dementia and lung cancer caregivers; 57% of wives and 29% of husbands | CES-D | Hospice family caregivers are at high risk for both psychological and physical health disorders; caregiver depression and health problems should be systematically assessed and treated by the hospice team. | 12 |

| Kilbourn et al. (2011) | To examine the feasibility of the Caregiver Life Line intervention for caregivers of home-based hospice patients to inform the design of a future randomized clinical trial (RCT) N=19 |

Foundation | Mean baseline CES-D = 15.3a | CES-D | Depression scores decreased with intervention; intervention was feasible. | 9 |

| Kris et al. (2006) | To examine the association between patient length of hospice enrollment and major depressive disorder among the surviving primary family caregivers 13 months after the patient’s death. N=175 |

Foundation, NIMH, NCI | 28% at baseline | SCID | Baseline depression did not differ significantly based on hospice lengths of enrollment. The effect of very short hospice length of enrollment was significantly associated with elevated risk of caregiver depression 13 months post- loss. | 9 |

| Ladner & Cuellar (2003) | To determine if hospice caregivers in rural settings were depressed and, if so, if they accessed treatments N=30 |

Not reported | 40% | CES-D | 40% of caregivers were depressed, yet only 17% were being treated for depression. Married caregivers were more depressed than single caregivers. Male caregivers were more depressed than female caregivers. | 0 |

| McMillan, Small, & Haley (2011) | To determine the efficacy of providing systematic feedback from standardized assessment tools for hospice patients and caregivers N=709 |

NINR | Not reported | CES-D | Providing team with feedback from instruments did not result in any significant differences in caregiver-related depression, support, and spiritual needs. | 17 |

| Mickey, Pargament, Brant, & Hipp (1998) | 1) To describe both religious and nonreligious appraisals of hospice caregiving 2) To explore the relationship between these appraisals with situational, mental health, and spiritual health outcomes N=92 |

University | Not reported | CES-D | Religious appraisals did not have a significant effect on caregiver depression. | 8 |

| Prigerson et al. (2003) | 1) To use the SCARED scale to examine the frequency of specific caregiver exposures involving patient distress and the fear and helplessness they evoke, and 2) To examine the extent to which these experiences are associated with depression and quality-of-life impairments N=76 |

Not reported | 30.3% | SCID | The SCARED scale total and event frequency scores were significantly associated with increased odds of depression and increased impairment in several quality of life domains. | 7 |

| Rivera & McMillan (2010) | To examine caregiver and patient factors as predictors of depression symptoms and level of depression symptoms in caregivers of hospice cancer patients N=578 |

Not reported | 37.5% had a score predictive of depression | CES-D | Wives who were caregivers were more depressed than husbands who were caregivers. Better health was associated with lower depression and high life satisfaction. Caregivers who reported that self-care and behavioral problems in the patient were subjectively upsetting had higher depression. | 10 |

| Walsh & Schmidt (2003) | 1) To evaluate recruitment and intervention protocols for the Tele-Care II intervention 2) To test the feasibility of a pre-post test assessment package 3) To measure the results of the intervention N=6 |

University | Not reported | CES-D | Caregiver depression scores decreased after the intervention. | 8 |

Analysis of the methodological rigor found that all but one of the studies employed statistical analysis for evaluation and hypothesis testing. Based on the modified Gysles and Higginson (2007) model, the quality of the evidence was varied, as scores ranged from 1–17. There were three studies with scores that indicated weak evidence, and one study with a score of 17, indicating it was strong evidence. The strength of the majority of the evidence was moderate. One study was a mixed methods study, and the qualitative score of eight reflected moderate strength of evidence, matching the moderate score of nine for its quantitative component.

Measurement of Depression in Hospice Caregivers

Within these 16 studies there were four different instruments utilized to assess hospice caregiver depression. The most common instrument was Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D), used in 10 studies. The next most common tool was the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (SCID), used in five of the projects. The remaining project used both the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Hamilton Psychiatric Rating Scale for Depression (HPRSD).

Frequency of Depression in Hospice Caregivers

In examining the evidence concerning the frequency of depression among caregivers in hospice, nine articles reported a prevalence percentage for depression. The reported range of frequency of depression reported in the identified study samples was between 26% and 57% at baseline measure. There was not a consistent time point following hospice enrollment that this baseline measure was assessed. Some studies obtained baseline measures shortly following hospice enrollment, while others did so days or weeks following hospice enrollment. The effect of this variance in timing of assessment on the accuracy of the prevalence is unknown.

Interventions for Depression in Hospice Caregivers

There were three intervention studies designed to address depression. One intervention, a randomized trial, hypothesized that providing an assessment of depression and other outcomes to hospice teams would result in better outcomes. There was no significant improvement in caregiver outcomes and the intervention was not deemed successful in addressing caregiver-related concerns (McMillan et al., 2011). The second and third intervention studies tested the feasibility of caregivers’ participation in a telephone support program. While the hospice caregivers’ depression decreased, both studies were limited with small sample sizes (Kilbourn et al., 2011; Walsh & Schmidt, 2003).

Discussion

While the review revealed that there has been some intervention research done with caregiver depression as an outcome, the evidence is sparse and noticeably weak in its methodological rigor. The majority of the research in this area is descriptive in nature and consists of small pilot studies. There is noticeable inconsistency in the demographics collected among studies and a lack of attention to the assessment of physical health measures, despite the mental health literature that consistently ties depression and physical health (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2007). Two specific tools, the CES-D and SCID, dominated these studies as depression measures. The question as to which instruments best measure depression in the hospice caregiver population, however, is still unknown and has not been thoroughly evaluated.

Using even the most conservative estimates of prevalence for d7%epression, more than a quarter of caregivers, it is clear that a significant number of hospice caregivers are suffering from depression. It is also evident that we do not have a strong amount of evidence supporting any one intervention or approach to treating this problem within the hospice setting. The bereavement studies provide indication that perhaps depression experienced by hospice caregivers is situational in nature, as most caregivers’ depression fell below a clinical threshold post-caregiving. However, this conclusion cannot be definitive based on the evidence from the small number of existing studies.

The reviewed studies indicated that women may be more depressed than men in hospice caregiving situations and that the diagnosis of the patient has little impact on the caregiver’s depression. Once again, the limitations of the existing research do not allow us to make definitive conclusions regarding the relationship between any demographic variables and hospice caregiver depression; however, these indications can be helpful in facilitating additional research on these relationships.

The interventions in these studies had mixed results. It is clear from the McMillan (2011) study that assessment of caregiver depression alone does not result in effective treatment. This is an important finding as it informs researchers that future work should address both assessment and treatment modalities. This may indicate that treatment of depression may not be a common skill within hospice teams in the same way that the treatment of physical pain may be. Research and science in the physical management of pain was found by the Agency on Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) to be the strongest focus in palliative care, while research on the psychosocial treatment issues was nearly non-existent (Dy et al., 2012). Intervention research from this review finds promise in interventions focused on social support, a known approach within mental health for addressing depression (Dy et al., 2012). While the studies reviewed here are limited by small sample size and weak methodological rigor, they do provide promising pilot data that interventions focusing on increasing social support in active caregiving hold promise on affecting change on levels of depression.

The support of the NIH for these studies is also noteworthy and encouraging. The NIH has only recently begun supporting research in end-of-life care, and the NINR has been the lead institute in funding this area (Aziz, Miller, & Curtis, 2012). The area of caregiver depression is an excellent example of necessary research in palliative medicine and hospice where multi-institute support seems appropriate.

Conclusion

Although research is sparse and varies in methodological rigor, there is evidence that depression is a common concern for hospice caregivers. Despite its prevalence, consistent assessment and evidence-based interventions for use by hospice professionals are limited. These conclusions are consistent with findings from other studies on hospice caregiving that concluded that the amount of evidence is small and the rigor is less than desirable (Aziz et al., 2012). Additional randomized controlled trials are needed to test the effectiveness of measurement instruments, assessment processes, and interventions for the treatment of depression in hospice caregivers. The NIH appears to be supportive of funding for these studies and researchers could assist the hospice practice community by embracing the opportunity to build the necessary evidence base to address the quality of life for hospice caregivers.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The project described was supported by Award Number R01NR011472 (PI: Parker Oliver) from the National Institute of Nursing Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health. The project is registered as a clinical trial record NCT01211340.

Contributor Information

Debra Parker Oliver, Email: oliverdr@missouri.edu, Curtis W. and Ann H. Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri, Medical Annex 306G, Columbia, Mo 65212, 573-356-6719.

David L. Albright, MU School of Social Work, University of Missouri.

Karla Washington, Kent School of Social Work, University of Louisville.

Elaine Wittenberg-Lyles, University of Kentucky, Markey Cancer Center and Department of Communication.

Ashley Gage, School of Social Work, Senior Research Specialist, University of Missouri.

Megan Mooney, University of Missouri.

George Demiris, Biobehavioral Nursing and Health Systems, School of Nursing & Biomedical and Health Informatics, School of Medicine, University of Washington.

References

- Ani C, Bazargan M, Hindman D. Depression symptomatology and diagnosis: Discordance bbetween physicians in primary care settings. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz NM, Miller J, Curtis JR. Palliative and end-of-life care research: Embracing new opportunities. Nursing Outlook. 2012;60:384–390. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block S. Assessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:209–218. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D, Smith N, Wright M, Winslow M, Hughes N. A bit of heaven for the few? An oral history of the modern hospice movement in the United Kingdom. Lancaster, UK: Observatory Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dy S, Aslakson R, Wilson R, Fawole O, Lau B, Martinez K, Bass E. Improving health care and palliative care for advanced and serious illness. 208. Baltimore, MD: AHRQ; 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladjchen M. Caregivers in palliative care: Roles and responsibilities. In: Altilo T, Oytis-Green S, editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Social Work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Gough K, Hudson P. Psychometric propoerties of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in family caregivers of palliative care patients. J Pain and Symptom Mgt. 2009;37(5):797–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Cloud GC, Wilson N, Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Wilson N. Informal primary carers of stroke survivors living at home-challenges, satisfactions and coping: a systematic review of qualitative studies. [Review] Disability & Rehabilitation. 2009;31(5):337–351. doi: 10.1080/09638280802051721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Systematic Reviews. In: Addington-Hall J, Bruera E, Higginson IJ, Payne S, editors. Research methods in palliative care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 115–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann C, Looney S. The effectiveness of symptom management in hospice patients during the last seven days of life. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2001;3(3):88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourn K, Costenaro A, Madore S, DeRoche K, Anderson D, Keech T, Kutner J. Feasibility of a telephone-based counseling program for informal caregivers of hospice patients. J Pall Med. 2011;14(11):1200–1205. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau D, Joyce B, Clayman M, Ehrlich-Jones L, Emanuel L, Hauser E, Shega J. Hospice providers’ key approaches to support informal caregivers in managing medications for patients in private residences. J Pain and Symptom Mgt. 2012;43(6):1060–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau DT, Berman R, Halpern L, Pickard AS, Schrauf R, Witt W. Exploring factors that influence informal caregiving in medication management for home hospice patients. J Palliative Medicine. 2010;13(9):1085–1090. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan SC. Interventions to facilitate family caregiving at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8(Supp 1):S132–139. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan SC. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan SC, Small BJ, Haley WE. Improving hospice outcomes through systematic assessment. Cancer Nursing. 2011;34(2):89–97. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f70aee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Correlates of physcial health of informal caregivers: A meta analysis. Journals of Gerontology. 2007;62(2):126–137. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.p126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C. Cicely Saunders: Selected Writings 1958–2004. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1963. The Treatment of Intractable Pain in Terminal Care; pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S, Schmidt L. Telephone support for caregivers of patients with cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26(6):448–453. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder H, Parker Oliver D, Demiris G, Washington K. Informal Hospice Caregiving: The Toll on Quality of Life. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care. 2008;4(4):312–332. doi: 10.1080/15524250903081566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]