Abstract

Conditional cash transfers (CCT) have recently received considerable attention as a potentially innovative and effective approach to the prevention of HIV/AIDS. We evaluate a conditional cash transfer program in rural Malawi which offered financial incentives to men and women to maintain their HIV status for approximately one year. The amounts of the reward ranged from zero to approximately 3–4 months wage. We find no effect of the offered incentives on HIV status or on reported sexual behavior. However, shortly after receiving the reward, men who received the cash transfer were 9 percentage points more likely and women were 6.7 percentage points less likely to engage in risky sex. Our analyses therefore question the “unconditional effectiveness” of CCT program for HIV prevention: CCT Programs that aim to motivate safe sexual behavior in Africa should take into account that money given in the present may have much stronger effects than rewards offered in the future, and any effect of these programs may be fairly sensitive to the specific design of the program, the local and/or cultural context, and the degree of agency an individual has with respect to sexual behaviors.

1 Introduction

Since the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, various strategies have been put in place to curb the spread of the disease and prevent further infections. There is on-going research focusing on ways to reduce the HIV transmission rate such as treating of other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), vaccines and microbicides, and male circumcision. The majority of HIV prevention strategies have targeted behavior change, encouraging individuals to shift from risky to less risky sex. These strategies thus promote programs such as education about the disease and how to protect oneself, HIV testing to know one’s own or one’s partner’s status, condom promotion, community, peer, and faith-based group advocacy, HIV de-stigmatization campaigns, better negotiation of risk such as through condom use or partner selection, and the promotion of abstinence programs (for an in-depth review, see Bertozzi et al. 2006). However, despite these prevention efforts, evidence of dramatic behavior changes as a response to these programs in Africa is controversial and no single intervention has emerged as an established approach (McCoy et al. 2010).1

This paper evaluates a new HIV prevention strategy: offering financial incentives for individuals to maintain their HIV status. Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) have been found to be effective in a variety of settings (Fiszbein and Schady 2009). In the developing world, some of the most well known CCTs have involved incentives for households, parents, or children to engage in healthy behavior or to increase schooling attainment/performance. Important examples include Oportunidades (Progresa) in Mexico (Levy 2006; Lindert et al. 2006), the Bolsa Escola Program in Brazil (de Janvry et al. 2005; World Bank 2001), the Red de Proteccion Social program in Nicaragua (Maluccio and Flores 2005), as well as smaller programs in other developing countries (de Janvry and Sadoulet 2006; Lagarde et al. 2007). In developed countries, CCTs have also focused on specific health behavior such as stopping smoking (Giné et al. 2009; Volpp et al. 2009), losing weight (Charness and Gneezy 2009; Volpp et al. 2008a), or taking medicine (Volpp et al. 2008b). Until recently, there have been no programs that directly incentivized individuals to stay free of sexually transmitted diseases, although several such programs are currently underway, including a program that gave financial rewards for testing negative for non-HIV sexually transmitted diseases every few months in Tanzania (RESPECT) (de Walque et al. 2011; World Bank 2010b),2 and a program for adolescents in Mexico (Galarraga and Gertler 2010). Another program in Malawi found that conditional and unconditional cash transfers for adolescent girls were associated with lower rates of marriage (Baird et al. 2010) and HIV (World Bank 2010a). Recent press releases have heralded these conditional cash incentive programs as potentially promising and innovative approaches to HIV/AIDS prevention. The UC Berkeley news release about the RESPECT program for example begins “Giving out cash can be an effective tool in combating sexually transmitted infections in rural Africa” (Yang 2010), and this promise of CCT programs for HIV/AIDS infection has been widely reported in the media (Dugger 2010; Jack 2010; Over 2010; World Bank 2010a).

Our analyses question the “unconditional effectiveness” of such CCT program for HIV prevention. In particular, CCT programs that aim to motivate safe sexual behavior in Africa need to take into account that money given in the present may have much stronger effects than rewards in the future, and any effect of these programs may be fairly sensitive to the specific design of the program, the local and/or cultural context and the degree of agency individuals have with respect to sexual behaviors. We derive this conclusion from an evaluation of a conditional cash transfer program that was implemented in 2006 in rural Malawi. In 2006, approximately 1,300 men and women were tested for HIV. They were then offered financial incentives of random amounts ranging from zero to values worth approximately four month’s wage, if they maintained their HIV status for approximately one year. Throughout the year, respondents were asked about their sexual behavior three times, through interviewer-administered sexual diaries. Respondents were then tested for HIV and financial incentives were awarded based on whether they had maintained their HIV status. After the second round of testing, the incentives program stopped.

Using the randomized design, we evaluate the effects of being offered an incentive on reported sexual activity and condom use before the second round of HIV testing. We find no statistical difference in reported behavior between those offered incentives and those who were not over three rounds of data.3 In addition, there were no differential effects by time of the survey, gender, education, expectations, or measures of female empowerment of our respondents.

One important aspect to consider in interpreting our results is whether we should have expected financial rewards to affect changes in sexual behavior at all. Outside of an incentives program, if individuals rationally maximize their lifetime utility, they should optimally choose how much risky or safe sex to engage in. Individuals facing higher risks of infection should adjust their behavior to substitute towards safer sex (Oster 2007; Philipson and Posner 1995).4 Given that there is no cure for HIV, the cost of infection is high and would be arguable much higher than four months wage offered through the incentives program. On the other hand, there is a growing body of both theoretical and empirical literature in which individuals are hyperbolic, have difficulty with commitment, have addictive behaviors, substantially underestimate their survival probabilities and overestimate their probabilities of being HIV-positive, and/or fail to adequately update subjective assessments of their HIV status in response to new information such as HIV test results.5 The insights from behavioral economics are important for the evaluation of CCT programs as individuals who want to abstain from having sex or want to use a condom trade-off sexual pleasure in the present for future lifetime utility and possible rewards received through CCT programs. If individuals place a higher value on the present, then offering cash incentives could help increase the short-term benefits of engaging in safe sex in the present.

There are two other recent studies similar to ours. First, a similar program in Tanzania (RESPECT study) that randomly offered cash incentives to participants every four months (either ten dollars or twenty dollars) for remaining free of a set of curable sexually transmitted infections, including chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis (de Walque et al. 2011; World Bank 2010b). In that program, at the end of the trial period, 9 percent of participants eligible for the highest incentive amount tested positive for curable infections compared to 12 percent among the control group. These results thus suggest that enrollees in this program who were offered a $20 incentives experienced a 25% lower STI prevalence than the control group enrollees after one year (de Walque et al. 2011; Yang 2010). A second study in Malawi randomly offered girls and their parents approximately fifteen dollars each month if the girls attended school regularly as well as additional payments for school fees (given either to the school or the girl herself) as well as compensation equivalent to the cost of school fees among some of the girls (Baird et al. 2010). A year later girls offered the incentives were 6 percentage points more likely to be in school as well as less likely to be infected with HIV (1.2% versus the control group’s 3%) (World Bank 2010b).

In these cases there are some notable differences and similarities with the program we evaluate in this paper. A first difference is that the amount of cash offered in both programs were substantially larger in both cases. In the Tanzania project, the amount of cash offered mattered for their results within their study: the group eligible for the lower incentives had the same infection rate as the control group that was offered no payments. A second difference is that in the Tanzania case, any participant who tested positive for an STI during the study received free medical treatment throughout the program. To the extent that the incentive was offered for treatable STIs, obtaining outside treatment could have biased results towards finding effects on STIs. In the Malawi case, participants either received money with no conditions or received money if they attended school a certain percentage of days; the amount of money participants and their families received were substantially higher as well.

In the case of the Malawi Incentive Program that is evaluated in the present paper, the failure of the monetary incentive to motivate behavior change may be due to a number of different factors that may be context or program specific. Rural men and women in Malawi may be less likely to respond to financial incentives than higher risk individuals such as urban men and women or individuals who are not in a stable marital relationships. It may also be that the amount of money was too small to induce a change in behavior. Another possibility is that the offer of the financial reward one year in the future was too far away from the present to overcome hyperbolic discounting or that there were concerns by respondents about the creditability of receiving the incentive payment in about one year conditional on their HIV status.6 In the cases where these particular aspects are important for respondents, conditional incentive payments may not affect short term decisions to engage in safer sexual behavior. These issues are therefore important in thinking through the design of future programs.

Although the conditional offer of money had no impact on reported sexual behavior, we find large effects of receiving money approximately one week after the second (and final) round of HIV testing when the incentive program had ceased. Men who received the money were 12.3 percentage points more likely to have vaginal sex and had approximately 0.5 days more of sex. While they were 5 percentage points more likely to report using a condom, overall on net there was a 9 percentage point increase in risky sex. On the other hand, women were 6.7 percentage points less likely to have engaged in risky sexual sex, a result that is driven by abstinence rather than increased condom use. The findings of the response to receiving the monetary transfer provides further evidence that money matters and can be protective for women. This finding also may have important implications for future CCTs offering financial incentives over time based on sexual behavior or STI status. In particular, the total effect of money may include two potentially asymmetric effects of the incentive offer and the direct effect of money itself. Importantly, the fact that we find no significant impact cautions policy makers to take care in considering CCT programs as a panacea for the HIV epidemic.

This paper proceeds as follows, Section 2 describes the experimental design and the data. Section 3 presents the estimates of the offered cash incentives on sexual behavior. Section 4 presents the effects of receiving the cash reward on sexual behavior. Section 5 concludes.

2 Malawi Incentives Project

2.1 Sample and Survey Data

The Malawi Incentives Project builds upon the Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP), a longitudinal study of men and women in three districts of rural Malawi. The original respondents in the MDICP study were randomly selected from 125 villages in 1998 and included ever-married women and their husbands; these individuals were re-interviewed in 2001. In 2004, an additional sample of randomly selected adolescent men and women (ages 14–24) from the same villages was added to the original sample. Each respondent in the original MDICP sample or in the adolescent refresher sample were eligible to be re-interviewed in 2006. It is important to note that while the respondents were representative at the time of the original sampling, some respondents attrited at each subsequent survey wave. During the surveys in 2004 and 2006 a separate team of nurses offered respondents free tests for HIV through either oral swabs (in 2004) or rapid tests (in 2006) (Anglewicz et al. 2009; Obare et al. 2009). We do not utilize the panel data from earlier waves of the study, but rather focus on a subsample respondents who were interviewed and accepted an HIV test in 2006.

Appendix A presents a time line of the incentives program. During the 2006 testing of the MDICP respondents, 92 percent of the respondents who were offered an HIV test accepted the test. Among these, the HIV prevalence rate was 9.2 percent. To enroll individuals into the Malawi Incentives Project, we randomly selected respondents from the 2006 MDICP survey, with a higher weight on HIV discordant couples (from their 2004 and 2006 HIV results). Of those who were tested for HIV in 2006, a total of 1,402 individuals were invited to participate in the incentives project. Those individuals were approached one to two months after the 2006 survey and HIV testing. A total of 1,307 (or 93%) were enrolled into the incentives program.

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the 1,307 individuals analyzed in this paper. 45 percent are male, with an average age of 36 years. The majority, 84 percent, were married. The sample is essentially rural and consists of individuals engaged in subsistence agriculture. Moreover, HIV for these individuals is a very salient disease. For example, respondents report knowing approximately eight friends who have died from AIDS, and while only 29 percent believe there is some likelihood of a current infection of HIV, 57 percent believe there is a future likelihood of becoming infected.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics

| Mean | Standard Dev | |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

|

| ||

| Male | 0.450 | 0.498 |

| Age | 35.783 | 12.963 |

| Married | 0.838 | 0.369 |

| Expenditures | 3130.286 | 5780.942 |

| Subjective Health | 2.065 | 0.935 |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners | 3.108 | 3.780 |

| Acceptable to use condom | 0.405 | 0.491 |

| Ever used condom with current partner | 0.263 | 0.440 |

| Fear about HIV | 1.593 | 0.752 |

| Number friends died of HIV | 8.197 | 8.045 |

| Some likelihood of HIV infection (current) | 0.287 | 0.453 |

| Some likelihood of HIV infection (future) | 0.566 | 0.496 |

| HIV positive at baseline | 0.087 | 0.282 |

| Enrolled as a “couple” | 0.238 | 0.426 |

Notes: This table presents baseline summary statistics among 1,307 respondents who participated in the incentives program. Expenditures are measured as household expenditures in the past 3 months (on clothes, schooling, medical expenses, fertilizer, agricultural inputs, and funerals). Subjective health represents self-reported health and was asked: “In general, would you say your health is: Excellent (1), Very Good (2), Good (3), Fair (4), Poor(5)”. Number of lifetime sexual partners includes any partner (long-term or short-term) that the respondent had sex with). Fear about HIV was asked as: “How worried are you that you might catch HIV/AIDS? Not worried at all (1), Worried a little (2), Worried a lot (3)”. Some likelihood of infection was coded one if the respondent answered low, medium, high, or don’t know and zero otherwise. Each variable was measured before incentives were offered.

2.2 Financial Incentives

At the time of the HIV test in 2006, individuals were randomly selected to be offered HIV counseling as either a couple, or as an individual.7 The majority, 76 percent, of those involved in the incentives project were tested as an individual. One to two months later, each individual was visited to introduce them to the incentives program. Each individual or couple randomly drew a token out of a bag to determine their incentive amount. The incentive amounts included zero, 500 Kwacha (approximately 4 dollars), or 2,000 Kwacha (approximately 16 dollars) for an individual, or zero, 1,000 Kwacha, or 4,000 Kwacha (approximately 32 dollars) for a couple. Each individual was given a voucher of the financial amount they randomly drew, and was told that they must maintain their HIV status in order to receive the money approximately one year later.8 Couples were told that both members of the couple must maintain their HIV status in order for the couple to receive the money.9 Couples who divorced, separated, or for whom one member was away, would receive one half of the couple incentives after one year if the individual who tested maintained his/her status. Because of the endogeneity of choice or ability to test as a couple or individual, this paper evaluates the effect of the program on individuals, rather than on the couple as a unit. Results are robust to controlling for the type of testing they received and point estimates change very little (results not shown).

The financial incentives were viewed as a significant amount among respondents. Most of the respondents are subsistence farmers, and based on Whiteside (1998), piecework daily rates (ganyu) for farm workers are approximately 20 Kwacha for men and 5–10 Kwacha for women. Several different experiments in Malawi have found large responses to very small incentive amounts. A program that offered cash incentives to learn their HIV results after testing found that even just 10 Kwacha increased the likelihood of traveling for results by almost 20 percentage points (Thornton 2008). Another study that randomly offered 30 Kwacha to individuals for a days work found that 80 percent of individuals showed up for work (Goldberg 2010).

It is important to note that the financial incentive was not specifically tied to being HIV-negative at the second round of testing. In particular, the sample for the Malawi Incentive Project included HIV-negative persons and HIV-positive persons (including, but not exclusively, respondents who were part of a discordant couple) in order to avoid the possibility that an exclusion from enrollment in the study would signal to outsiders information about a MDICP respondent’s HIV status. If an HIV-positive individual was enrolled as an individual (due to a spouse being away, or a spouse not giving consent to couple counseling), he or she would automatically receive the monetary amount at the end of the study (conditional in participating in the final HIV test and survey). In the analysis we only examine the effect of the incentive among those who were HIV-negative at the beginning of the study although results are robust to including HIV-positives (results not shown).

The incentives were distributed between the three levels, across both couples and individuals, with an equal probability of receiving each incentive amount. In practice, the realized (ex-post) distribution of the incentives resulted in 35 percent receiving zero, 32 percent receiving a medium-level incentive, and 33 percent receiving a high-level incentive. The distribution of the incentives given out was roughly identical to the theoretical distribution. We cannot reject that the realized and theoretical distributions of incentives is equal using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for equality of distributions (p-value of 0.997, not shown).

Table 2 presents baseline summary statistics among those offered zero, medium, and high amounts of the incentive. For almost each variable there is no significant effect of incentives. In comparing some of the averages across incentive groups, there are some significant differences, (for example, age and self-reported health), these differences are small in magnitude and we also include these demographic controls in the analysis.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics by Incentives Offered

| Zero Incentive (N=455) | Medium Incentive (N=420) | High Incentive (N=432) | p-value of joint test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|

| ||||

| Male | 0.446 | 0.469 | 0.435 | 0.59 |

| Age | 34.804 | 35.521 | 37.069 | 0.03 |

| Married | 0.844 | 0.831 | 0.838 | 0.87 |

| Expenditures | 3013.769 | 3131.010 | 3250.368 | 0.84 |

| Subjective Health | 2.031 | 2.000 | 2.163 | 0.03 |

| Number of lifetime sexual partners | 2.940 | 3.349 | 3.053 | 0.32 |

| Acceptable to use condom | 0.400 | 0.392 | 0.424 | 0.62 |

| Used condom with current partner | 0.261 | 0.257 | 0.271 | 0.89 |

| Fear about HIV | 1.597 | 1.579 | 1.603 | 0.89 |

| Number friends died of HIV | 7.816 | 8.581 | 8.222 | 0.40 |

| Some likelihood of HIV infection (current) | 0.294 | 0.288 | 0.280 | 0.92 |

| Some likelihood of HIV infection (future) | 0.593 | 0.557 | 0.547 | 0.38 |

| HIV positive at baseline | 0.105 | 0.088 | 0.067 | 0.13 |

| Enrolled as a “couple” | 0.209 | 0.240 | 0.266 | 0.13 |

Standard errors in parenthesis

signifcant at 10%;

signifcant at 5%;

signifcant at 1%

Notes: This table presents baseline demographic statistics by incentives amounts among 1,307 respondents who participated in the incentives program. Expenditures are measured as household expenditures in the past 3 months (on clothes, schooling, medical expenses, fertilizer, agricultural inputs, and funerals). Subjective health represents self-reported health and was asked: “In general, would you say your health is: Excellent (1), Very Good (2), Good (3), Fair (4), Poor(5)”. Number of lifetime sexual partners includes any partner (long-term or short-term) that the respondent had sex with). Fear about HIV was asked as: “How worried are you that you might catch HIV/AIDS? Not worried at all (1), Worried a little (2), Worried a lot (3)”. Some likelihood of infection was coded one if the respondent answered low, medium, high, or don’t know and zero otherwise. Each variable was measured before incentives were offered.

2.3 Sexual Diaries and HIV Testing

Approximately three to six months after the incentives were offered and vouchers given out, respondents were interviewed in their homes and asked about their recent sexual behavior. In particular, asked about the previous nine days, asking sexual activities and condom use each day. These interviewer administered diaries were collected three times over the period of the study, which we identify as Round 1, Round 2, and Round 3, respectively. These were unannounced visits that occurred approximately every three months; the same questionnaire was administered each time. At the end of the third round, respondents were visited by a project nurse and were offered another HIV test. This HIV test was tied to the financial incentives and thus was required in order to be eligible to receive any of the financial incentives.

At the end of the study, of the 1,076 HIV-negative individuals who took a test at the follow-up, seven were HIV positive. This is an incidence rate of less than one percent. It is important to note that the study was not originally designed to be powered to detect changes HIV incidence, which would require a much larger sample size. Instead, we designed the study to examine the effects on sexual activity, including condom use (see also Section 4.1 and footnote 12). It is also important to note that while initially discordant couples were over-represented in the sample, there were actually quite few at baseline and then followed until the end of the study, thus making it difficult to analyze effects among these couples.

Table 3 Panel A presents attrition statistics across each round of sexual diary and obtaining a follow-up HIV test. Approximately 93 percent of the sample completed round 1 diaries, 89 percent completed round 2 diaries, and 92 percent completed round 3 diaries. Men (who tend to be more mobile in Malawi) were less likely to complete rounds (between 3.0 and 4.2 percentage points less than women; results not shown). Individuals who were HIV positive in 2006 were less likely to complete rounds, and this became more of a factor over time. HIV-positives were 6.6 percentage points less likely to complete round 1 diaries, 9.9 percentage points less likely to complete round 2 diaries, 10 percentage points less likely to complete round 3 diaries, and 20 percentage points less likely to take the follow-up test. Almost all of the respondents (98 percent) completed at least one round of diaries, with an average of 2.7 rounds. At the end of the study, 89 percent of all enrolled respondents obtained a follow-up HIV test after round 3. Panel B presents attrition statistics among HIV-negatives who form the main sample for the analyses in the remainder of the paper.

Table 3.

Attrition/Survey Completion Rates

| Panel A: Entire Sample | All | Zero Incentive | Medium Incentive | High Incentive | p-value of joint test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|

| |||||

| Enrolled in Incentives Project | 1307 | 455 | 420 | 432 | -- |

| Completed Round 1 | 0.929 | 0.921 | 0.921 | 0.944 | 0.31 |

| Completed Round 2 | 0.889 | 0.884 | 0.902 | 0.882 | 0.57 |

| Completed Round 3 | 0.916 | 0.890 | 0.931 | 0.928 | 0.05 |

| Completed at Least One Round | 0.979 | 0.971 | 0.988 | 0.977 | 0.23 |

| Completed Each Round | 0.829 | 0.802 | 0.845 | 0.843 | 0.16 |

| Number rounds completed | 2.734 | 2.695 | 2.755 | 2.755 | 0.29 |

| Follow-up HIV Test | 0.884 | 0.820 | 0.910 | 0.928 | 0.00 |

| Panel B: HIV Negatives | All | Zero Incentive | Medium Incentive | High Incentive | p-value of joint test |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|

|

|||||

| Enrolled in Incentives Project | 1193 | 407 | 383 | 403 | -- |

| Completed Round 1 | 0.935 | 0.929 | 0.927 | 0.948 | 0.41 |

| Completed Round 2 | 0.898 | 0.892 | 0.914 | 0.888 | 0.45 |

| Completed Round 3 | 0.925 | 0.899 | 0.940 | 0.935 | 0.06 |

| Completed at Least One Round | 0.983 | 0.975 | 0.992 | 0.983 | 0.19 |

| Completed Each Round | 0.840 | 0.816 | 0.856 | 0.849 | 0.25 |

| Number rounds completed | 2.757 | 2.720 | 2.781 | 2.772 | 0.33 |

| Follow-up HIV Test | 0.902 | 0.848 | 0.924 | 0.935 | 0.00 |

Standard errors in parenthesis

signifcant at 10%;

signifcant at 5%;

signifcant at 1%

Notes: This table presents survey completion rates by incentives amounts. The sample includes 1,307 respondents who participated in the incentives program. Panel B exludes 114 individuals who were HIV positive at baseline.

Importantly, completion rates of sexual diary rounds and obtaining a follow-up HIV test are correlated with the incentive offered. Those who were offered incentives (and in some cases, higher levels of incentives) were more likely to complete sexual diaries and were more likely to take the HIV test at the end of the study. But only in a few cases (2 out of seven), the difference in attrition between the different incentive levels is statistically significant. Although in each round respondents received a small gift for their participation (soap), those who were not offered a financial reward may have had a lower return in continuing to answer survey questions. They would also had little potential gain in participating in an follow-up HIV test after having already learned their status one year earlier. If attritors who were offered the incentive were also more likely to have engaged in riskier sex, then our estimates of the effectiveness of the program on safe sexual behavior would be upwardly biased. We would under-estimate the true effect if the pattern of differential attrition was reversed. If we check for differential attrition by interacting indicators of baseline risky sexual behavior (HIV status in 2006, ever using a condom, or number of sexual partners) and the incentive, there is no significant effect on completing any round (not shown). There was also no differential attrition on completing at least one round of sexual diaries. For our analysis below, we first pool our results across all three rounds of sexual diaries, mitigating the effects of differential attrition at each single round. Another strategy is be to use baseline observable characteristics construct inverse probability weights. This procedure predicts the probability that an individual has not attrited; the inverse of this probability is the weight in each regression. Thus, individuals who are more likely to having missing sexual diary rounds are given more weight. The main results reported below do not differ substantially using these weights (results not shown).

From the information in the diaries, we use several indicators of risky or safe sexual behavior. These include being pregnant at any of the rounds measured only among women, having any vaginal sex (during the nine days of the sexual diary), the number of days having vaginal sex, whether or not the respondent used a condom during the days of the diary conditional on having sex, and if condoms were present at home. We also construct a composite variable indicating whether the respondent had safe sex—that is, it is equal to one if the respondent had sex with a condom or had no sex at all.10 Across all three rounds, 8.6 percent of women are pregnant, 53 percent engage in vaginal sex across the nine days of diary collection with an average of 1.5 days of sex (across the three rounds). Across the rounds, 12.6 percent report using a condom. In each of the rounds, only 12.1 percent reported having condoms at home. 55.6 percent of respondents practiced “safe sex”—either abstaining or using a condom. We find no evidence of recall bias when comparing the reported number of sexual encounters on the first day of the diary (ie. “yesterday”) with the last day of the diary (ie. “day 9”).

3 Empirical Strategy

Using the fact that the incentives were randomly offered, to empirically measure the impact of financial incentives on reported sexual behavior, we estimate the following specification:

| (1) |

Because the incentive project included individuals who were HIV positive at baseline primarily to protect the confidentiality of HIV status of responses, rather than for the identification of program effects, we estimate in this paper the effects of the incentives only among individuals who were HIV-negative at baseline. We first pool each of the rounds of the sexual diaries together. Y indicates reported sexual behavior for an individual i in round j. “Any Incentive” indicates that the individual was offered a positive (non-zero) incentive offer. “X” is a vector including indicators of gender, age, marital status, if the incentive was given as an individual or as a couple, HIV status in 2006, as well as district and sexual diary round dummies. Standard errors are clustered by individual for the pooled regressions. In addition to pooling rounds, we estimate the above equation separately for each round; for these specifications we pool by village.11

In a simple comparison of means which does not include any controls or adjustments in standard errors, the results are unchanged (Appendix B). In addition to measuring the effect of being offered any incentive, we could also include dummy variables indicating whether respondents were offered medium-valued or high-valued incentives. All of the results are robust to this alternative specification (Appendix C). Another approach would be to only include the entire sample of those who were HIV-positive in 2006. The main results do not differ substantially among a pooled sample of HIV-positives and HIV-negatives (not shown). Although we run linear specifications, results are also robust to non-linear models when we have a binary outcome variable as well as using person-day observations.

Our primary coefficient of interest is β, which measures the impact of being offered a financial incentive on reported sexual behavior. While typically, financial status is correlated with other omitted variables which also influence sexual behavior, because the incentives were randomly allocated, β is an unbiased estimate of the impact of cash offered on sexual behavior. We present how the baseline characteristics correlate with the incentives amount in Table 2. In general, there were few significant differences in baseline variables across incentive amounts.

It is worth remarking on the fact that we report effects on follow-up HIV status and reported sexual behavior. In general, there was no direct benefit for respondents to overstate their safer sexual practices to the interviewers. To the extent that misreporting is not correlated to the randomized incentives, there is no reason to worry about biased estimates. On the other hand, even though respondents were no more likely to earn their incentive money if those offered larger incentive amounts did in fact overstate their safe sexual behavior because they perceived some greater benefit from doing so, our estimates would be an upper bound of the true effect of the program. Because our main findings suggest an absence of important effects of the incentive payments on reported sexual behaviors, our conclusion is conservative with respect to misreporting in which individuals with higher incentives report safer sexual practices.

4 Effects of Offering a Financial Incentive

4.1 Results

This section reports our main results of the effect of being offered financial incentives on reported sexual behavior. We first pool all three rounds of reported sexual behavior and estimate average effects of being offered a financial incentive.

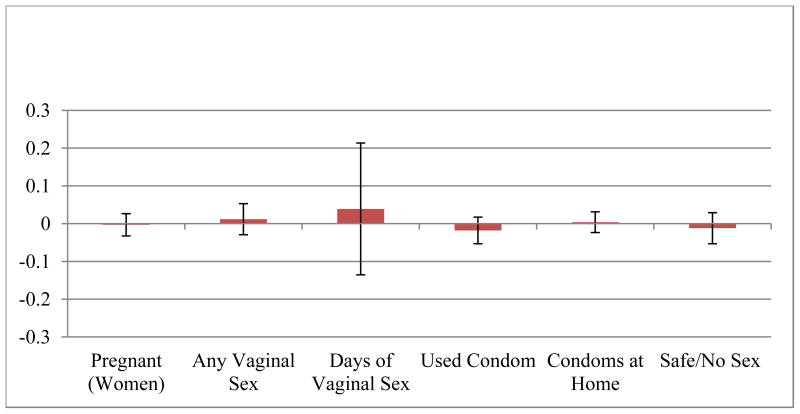

Table 4 presents the main results of the impact of being offered any incentive to maintain HIV status with the control-group means of each dependent variable in the last row. There are no significant effects of the incentive on any measure of reported sexual behavior. Not only are the coefficients not statistically significant, the size of the coefficients are small. Figure 1 graphs the coefficients, with 95% confidence bars to illustrate the relatively small point estimates. Power calculation suggest that our incentive project, with an enrollment of about 1,200 HIV-negative individuals at baseline of whom 84% participated in all three rounds of sexual diaries, would have been able to detect: with a probability of more than 90% (with α = .1), a 15% increase in having any vaginal sex during the nine days prior to each of the sexual diaries in response to receiving any incentive, a 15% increase in having safe sex—that is, it is equal to one if the respondent had sex with a condom or had no sex at all—during these periods, or a 15% decline in the number of days with vaginal sex during these periods. Our sample size would have allowed us to detect with a probability of more than 75% a 25% increase the probability of using condoms (conditional on having sex) or having condoms at home in response to receiving any incentives; with more than 80% probability our study would have detected a 40% reduction in the probability of a women being pregnant.12 The study was therefore adequately powered to detect changes in sexual behaviors at the magnitude that is suggested by other studies about the effect of financial incentives or HIV prevention programs on sexual behaviors, and these power calculations along with the small point estimates and relatively small standard errors for the coefficients (Figure 1) indicate that the incentive project did not substantially change sexual behaviors in response to receiving financial incentives that reward maintaining one’s HIV status.

Table 4.

Impact of Incentive Offer on Reported Sexual Behavior, All Rounds HIV Negatives

| Pregnant (Women) | Any Vaginal Sex | Days of Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Condoms at Home | Safe/No Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|

| ||||||

| Any Incentive | −0.003 [0.015] | 0.012 [0.021] | 0.039 [0.089] | −0.018 [0.018] | 0.004 [0.014] | −0.012 [0.021] |

| Male | 0.136*** [0.020] | 0.455*** [0.089] | 0.094*** [0.018] | 0.082*** [0.014] | −0.099*** [0.020] | |

| Married | 0.029 [0.022] | 0.315*** [0.029] | 0.910*** [0.106] | −0.045 [0.044] | 0.076*** [0.019] | −0.280*** [0.026] |

| Age | −0.005 [0.003] | 0.003 [0.005] | 0.041** [0.018] | −0.011** [0.005] | −0.004 [0.003] | −0.005 [0.004] |

| Age-squared | 0.000 [0.000] | −0.000 [0.000] | −0.001*** [0.000] | 0.000 [0.000] | 0.000 [0.000] | 0.000* [0.000] |

| Some school | −0.023 [0.017] | 0.022 [0.026] | 0.097 [0.106] | −0.006 [0.019] | 0.025* [0.014] | −0.025 [0.025] |

| Number of children | −0.005 [0.003] | 0.013*** [0.004] | 0.060*** [0.017] | −0.003 [0.003] | −0.003 [0.002] | −0.016*** [0.004] |

| Rumphi | 0.003 [0.018] | −0.089*** [0.025] | −0.033 [0.116] | 0.140*** [0.022] | 0.054*** [0.018] | 0.172*** [0.025] |

| Balaka | 0.009 [0.019] | −0.133*** [0.025] | −0.293*** [0.105] | 0.020 [0.020] | 0.008 [0.016] | 0.112*** [0.025] |

| Round 2 | −0.002 [0.013] | −0.022 [0.018] | −0.078 [0.067] | −0.003 [0.016] | −0.001 [0.012] | −0.037** [0.018] |

| Round 3 | −0.002 [0.017] | −0.046** [0.019] | −0.025 [0.078] | −0.026 [0.017] | −0.016 [0.012] | −0.020 [0.019] |

| Constant | 0.249*** [0.070] | 0.253*** [0.089] | 0.046 [0.342] | 0.373*** [0.091] | 0.124** [0.058] | 0.871*** [0.087] |

| Observations | 1,777 | 3,258 | 3,258 | 1,748 | 3,258 | 3,258 |

| R-squared | 0.036 | 0.095 | 0.064 | 0.089 | 0.045 | 0.087 |

| Mean of dep var in control group | 0.095 | 0.535 | 1.538 | 0.1294 | 0.112 | 0.5471 |

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%

Note: All columns present OLS regressions. Robust standard errors clustered by individual, in brackets. “Used a condom” is conditional on reported sexual activity. “Safe Sex or No Sex” is equal to one if the respondent abstained from sex or used a condom and zero otherwise.

Figure 1. Effect of Incentive Offer on Reported Sexual Behavior.

Notes: This figure presents the coefficients on “Any Incentive” and 95% confidence intervals from OLS regressions in table 4 of the pooled round 1, round 2 and round 3 observations.

To the extent that individuals receiving higher incentives may have felt the need to over-report safe sexual behavior to interviewers, these results are overestimates of the true effect of the incentive on actual sexual behavior. Appendix C also reports the effect of different amounts of incentive (low or high) as compared to being offered no incentive.

The covariates in the table are of expected signs and magnitudes. Married individuals are significantly more likely to engage in sex and less likely to use a condom. Men report more sexual activity but more condom use/ownership. Individuals who are HIV positive are less likely to report having sex and more likely to report using condoms and having condoms at home. There are also sharp differences in reported sexual behavior between districts (Rumphi, Balaka, and Mchinji) which could be due in part to ethnic or geographic differences.

Table 5 presents the estimates separately for each round of data collection. Again, there are no statistically significant effects of being offered the incentive during any round or for any variable. In addition to the main set of variables, we also present the effects on HIV status during round 3. Overall there appears to be little impact of the offer of the incentive on any sexual behavior.

Table 5.

Impact of Incentive Offer on Reported Sexual Behavior, Separate Rounds HIV Negatives

| Dependent Variable: | HIV Positive (Round 3) | Pregnant (Women) | Any Vaginal Sex | Days Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Condoms at Home | Safe/No Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Round 1 | “Any Incentive” Coefficient | -- | 0.020 | 0.039 | 0.145 | −0.031 | 0.006 | −0.029 |

| -- | [0.027] | [0.033] | [0.111] | [0.025] | [0.021] | [0.033] | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Observations | 601 | 1,101 | 1,101 | 621 | 1,101 | 1,101 | ||

| R-squared | 0.040 | 0.085 | 0.072 | 0.133 | 0.066 | 0.075 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Mean of dep var in control group | -- | 0.084 | 0.539 | 1.493 | 0.144 | 0.117 | 0.576 | |

| Round 2 | “Any Incentive” Coefficient | -- | −0.007 | −0.011 | −0.061 | −0.010 | −0.004 | 0.003 |

| -- | [0.023] | [0.029] | [0.118] | [0.029] | [0.020] | [0.033] | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Observations | 579 | 1,064 | 1,064 | 574 | 1,064 | 1,064 | ||

| R-squared | 0.037 | 0.102 | 0.077 | 0.122 | 0.057 | 0.106 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Mean of dep var in control group | -- | 0.097 | 0.551 | 1.562 | 0.141 | 0.121 | 0.521 | |

| Round 3 | “Any Incentive” Coefficient | 0.001 | −0.022 | 0.008 | 0.031 | −0.012 | 0.011 | −0.008 |

| [0.005] | [0.022] | [0.028] | [0.117] | [0.028] | [0.017] | [0.028] | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Observations | 1,071 | 597 | 1,091 | 1,091 | 552 | 1,091 | 1,091 | |

| R-squared | 0.009 | 0.048 | 0.116 | 0.060 | 0.031 | 0.033 | 0.100 | |

|

|

||||||||

| Mean of dep var in control group | 0.006 | 0.105 | 0.515 | 1.562 | 0.104 | 0.097 | 0.543 | |

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%

Note: Each cell presents a separate OLS regression of the dependent variable on a dummy variable for whether the respondent was offered any incentive controlling for whether the respondent is male, married, has some schooling, HIV status at baseline, number of living children, and distric fixed effects. Robust standard errors clustered by village, in brackets.

4.2 Channels

There may be a variety of reasons as to why we might observe no effect of offering financial incentives on sexual behavior. We explore several of these channels in Appendix D by measuring heterogeneous responses to the incentive offer. One often-cited reason for the lack of observed behavior change in Africa in response to the HIV epidemic is that there is a lack of knowledge or awareness of how to change behavior. In theory, education, could be positively correlated to behavior change—either because individuals learn how to protect themselves from infection, or because education raises the return to staying un-infected (de Walque 2006; Oster 2007). While overall, the average years of education is quite low, at 4.5 years, with 23 percent having never attended school, there is essentially no differential impact of education on the response to being offered any incentive.

Another possibility to why there was no observed behavior change in response to the financial incentive is that the incentive amount was not enough to induce behavior change. Given the levels of poverty in this sample, it is difficult to reason that there were no individuals who would not have been affected on the margin and that we wouldn’t pick up changes in response to the monetary incentives. However, we can estimate any possible effects among those who are at different levels of income. While those which higher income are less likely to have sex and less likely to use a condom, there is no consistent pattern on the interaction between income and the incentive on our outcome variables.

Similarly, men and women could have responded differently to being offered incentives, either due to preferences, or ability to bargain on sexual behavior within the relationship. Again, there is no consistent pattern in the difference in the response to the incentive by gender. To examine whether bargaining power was important for women, we estimate the impact of the incentive among women who were more or less “empowered”. We construct an index by taking an average of a series of attitudinal questions related to gender empowerment.13 This index ranges from zero to one with an average value of 0.47. Higher values of the index indicates higher levels of empowerment. We estimate differential effects among females only and again there appears to be no differential response.

Overall, the results indicate no response to being offered the monetary incentive on the sample.14 This may be due to the fact that the monetary reward was too far in the future, that it was not enough money, or that these individuals were already optimizing prior to the incentive scheme. One possibility that we assert is less likely to be a reason for the limited effects is the credibility of receiving the incentives. These individuals were part of a larger longitudinal study which had previously offered—and distributed—financial rewards for traveling to a mobile clinic to learn their HIV results (Thornton 2008). It is therefore unlikely that the credibility of the program was the most critical factor.

5 Effects of Receiving a Financial Incentive

Approximately one week after the third round of sexual diaries, HIV testing, and distribution of the monetary incentives, interviewers returned to each respondent to administer the sexual diaries. Again, completion of a survey was correlated to incentive status. Overall, 91.6 percent were interviewed although this varied by no incentive (89.1 percent), medium incentive (93.1 percent) and a high incentive (92.9 percent). Seven individuals, who were HIV-negative at enrollment, tested HIV-positive in at the follow-up test and did not receive the financial reward.

Table 6, Panel B presents the effects of receiving the monetary incentives on sexual behavior, separately among men and women. These results are intention-to-treat effects as they do not exclude those who did not receive the incentives.15 Among men, those who received any incentive were 12.3 percentage points to engage in any vaginal sex and had 0.5 additional days of sex. Men who received incentives were also significantly more likely to report using a condom during sex (6.9 percentage points more likely), but overall, they were more likely to engage in riskier sex. These results are similar to findings in Luke (2006) who found that wealthier men were more likely to engage in sex but also more likely to use condoms. Women who received the incentive, on the other hand, were less likely to report having any vaginal sex and there was no impact on reported condom use. In some cases, the amount of the incentive also mattered—for example, among women, the largest effect of the incentive was among those who received the largest incentive, rather than the medium-valued incentive (Table 6 Panel C). For men on the other hand, there is no statistical difference between the response to high incentives and medium incentives.

Table 6.

Effect of Receiving Incentive on Reported Sexual Behavior, Round 4 HIV Negatives

| Panel A: Attrition to Round 4 Survey | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Zero Incentive | Medium Incentive | High Incentive | p-value of joint test | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|

|

|||||

| Completed Round 4 | 0.853 | 0.828 | 0.854 | 0.878 | 0.13 |

| Panel B: Effects of Receiving an Incentive on Sexual Behavior | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Any Vaginal Sex | Days Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Safe/No Sex | Any Vaginal Sex | Days Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Safe/No Sex | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|

|

||||||||

| Any Incentive | 0.123** [0.049] | 0.514** [0.213] | 0.052* [0.031] | −0.090** [0.045] | −0.074* [0.040] | −0.153 [0.183] | 0.000 [0.030] | 0.067* [0.038] |

|

|

||||||||

| Observations | 447 | 447 | 280 | 447 | 568 | 568 | 332 | 568 |

| R-squared | 0.135 | 0.085 | 0.135 | 0.183 | 0.057 | 0.025 | 0.017 | 0.048 |

|

|

||||||||

| Mean of dep var in control group | 0.538 | 1.490 | 0.078 | 0.497 | 0.644 | 1.892 | 0.055 | 0.392 |

| Panel C: Effects of Receiving an Incentive on Sexual Behavior | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||||

| Any Vaginal Sex | Days Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Safe/No Sex | Any Vaginal Sex | Days Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Safe/No Sex | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|

|

||||||||

| High Incentive | 0.131** [0.056] | 0.338 [0.231] | 0.041 [0.037] | −0.092* [0.055] | −0.046 [0.050] | −0.056 [0.221] | 0.020 [0.034] | 0.046 [0.045] |

| Low Incentive | 0.115** [0.053] | 0.688** [0.276] | 0.063 [0.040] | −0.088* [0.046] | −0.100** [0.044] | −0.243 [0.205] | −0.019 [0.032] | 0.087* [0.047] |

|

|

||||||||

| Observations | 447 | 447 | 280 | 447 | 568 | 568 | 332 | 568 |

| R-squared | 0.135 | 0.089 | 0.136 | 0.183 | 0.059 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.049 |

|

|

||||||||

| Mean of dep var in control group | 0.538 | 1.490 | 0.078 | 0.497 | 0.644 | 1.892 | 0.055 | 0.392 |

Notes: All coefficients are from OLS regressions. Control variables not shown. “Vaginal Sex” is a dummy variable equal to one if the respondent reported having had vaginal sex. “Used a Condom” is a dummy variable equal to one if the respondent reported using a condom. “Safe Sex or No Sex” is a dummy variable equal to one if the respondent either reported using a condom or reported not having sex. Each regression includes controls for whether the respondent is male, married, has some schooling, HIV status at baseline, number of living children, and distric fixed effects. Robust standard errors clustered by village, in brackets.

Researchers and policy makers have associated the lack of financial resources among women as a determinate of riskier sexual behavior because of the monetary transfers they receive from men (Dupas 2009; Hallman 2004; Halperin and Epstein 2004; Robinson and Yeh 2009; Shelton et al. 2005; Wines 2004; Wojcicki 2002). Similarly, researchers have hypothesized a positive relationship between male wealth and unsafe sexual behavior because men with higher incomes can afford to purchase riskier sex (e.g., Gertler et al. 2005; Luke 2006).16 Evidence quantifying the effects of income transfers on sexual behavior among men and women, however, is limited, and often confounded by omitted variables that bias causal estimates.17

There could be several mechanisms through which receiving the financial incentive affected sexual behavior among both the men and women. First, the money could have been a directly used by the men to purchase risky sex, and the money could have been used by the women to substitute away from “selling” risky sex. Another possible mechanism for men is that the incentive may have been a signal that the individual was HIV-negative. If everyone in the village knew about the incentives program, a man could use the earning of the incentive as an indication that he was not infected. Ironically, this could have resulted in an increase in risky sex. How exactly the money affected sexual behavior is worth exploring in future research.18

6 Conclusion

This paper presents the results from a conditional cash transfer program in rural Malawi where individuals were offered financial rewards to maintain their HIV status for approximately one year. We find no overall significant or substantial effects of being offered the reward on subsequent self-reported sexual behavior. Despite the fact that self-reports might be biased towards individuals over-reporting safe sexual behavior, we estimate small and statistically insignificant point estimates. Moreover, we find no evidence of possibly heterogeneous effects where incentives would affect sexual behavior among the more educated or the poorer individuals, and there is no evidence for differential effects according to female bargaining power. There is also no evidence that the largest incentive payments—which are equivalent to approximately four months of income for the average respondent in our study—have an effect on sexual behaviors. These findings of our study are in sharp contrast to some recent press reports and published findings of related conditional cash transfer programs that claim to document the effectiveness of conditional cash transfer programs for HIV prevention (e.g., de Walque et al. 2011; World Bank 2010b).

The findings of this paper add to the literature on conditional cash transfers and HIV prevention in two important ways. First, the finding of no impact of the financial reward on sexual behavior speaks to the design of future CCTs related to sexual transmitted diseases. The success of CCTs in promoting behavior change in other contexts has varied, often depending on the specific setting, design, and implementation (Filmer and Schady 2009; Fiszbein and Schady 2009). In particular, the effectiveness of a CCT program is dependent on the particular target population, conditions, enforcement, credibility, and payment levels. The lessons from this evaluation can thus help in the design of future evaluations and CCT programs and for understanding sexual behavior more generally. For example, it seems plausible that rewards offered in more frequent intervals over the year might be more effective in affecting sexual behavior than a one time reward offered in one year. In addition, it might be useful targeting individuals who are in less stable sexual relationships or who are more at risk such as unmarried adolescents.

Second, our study finds large and significant effects approximately one week after receiving the incentives money. Men who received money were 12 percentage points more likely to have vaginal sex and had approximately 0.5 days more of sex. While condom use among these men increased (by 5 percentage points), on net risky sex increased by 9 percentage points. On the other hand, women were 6.7 percentage points less likely to have engaged in risky sexual sex. Hence, sexual behaviors are clearly responsive to cash payments, possibly because of the income effect resulting from these payments, and the behavioral responses to receiving cash payments differ between men and women. These findings help to further quantify how men and women respond to money and raise additional important questions. Is there an increase in risky sex among men due to the fact that they purchase risky sex, or, is increase in income a signal to women that the men were HIV-negative? Did the men spend money on items that increased their level of attraction (such as purchasing new clothes or soap)? Additional investigation into the response of men and women to cash transfers is warranted. In particular, if giving men money increases their risky sex then studies that pay respondents may actually increase the risky sex in the study. This is related to work by Oster (2007) who finds a strong relationship between exports and HIV prevalence rates.

There are several arguments that have been posed for and against offering incentives for individuals to stay HIV-negative. The arguments against largely fall into two categories: ethics and efficacy. Concerns about coercion or equity have been raised by ethicists, which are somewhat parallel to arguments against other CCT programs and merit scholarships (Wadman 2008). In this sample, the HIV-positives were also given incentives for maintaining their own status, and given rewards for maintaining their partner’s status. While we saw no large effects of the reward, this particular design might help to get around concerns of ethics. In terms of the effect of the program, while we found no effect, we hope that the lessons learned will guide future program design. To the extent that there are social externalities of HIV, offering rewards might help to reduce the epidemic. If individuals can be incentivized during risky stages of life then such a cash transfer program could be cost effective. The result that money can be protective for women is encouraging, however, that men receiving money practiced riskier sex calls for caution in scaling up these type of programs as well as other poverty assistance programs.

Appendix A

Timeline

| 2006 | May – July | HIV Initial Testing + MDICP Surveys |

| August – December | Incentives Offered | |

| 2007 | April – May | Round 1 Sexual Diaries |

| July – October | Round 2 Sexual Diaries | |

| 2008 | March – August | Round 3 Sexual Diaries + HIV Testing + Incentives Given |

| March – August: 1–2 weeks after HIV testing | Round 4 Sexual Diaries |

Notes: The approximate project timeline is presented above. Three locations (Balaka, Mchinji, and Rumphi) were included across this time period.

Appendix B

Differences in Means of Reported Sexual Behavior by Incentive group, HIV Negatives

| Panel A: Rounds 1, 2, 3 - Effects of Incentive Offer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N=1193) | Zero Incentive (N=407) | Medium Incentive (N=383) | High Incentive (N=403) | p-value of joint test | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|

|

|||||

| Pregnant (Women) | 0.089 | 0.095 | 0.076 | 0.094 | 0.43 |

| Any Vaginal Sex | 0.538 | 0.535 | 0.542 | 0.539 | 0.95 |

| Days of Vaginal Sex | 1.546 | 1.538 | 1.603 | 1.499 | 0.48 |

| Used Condom | 0.118 | 0.129 | 0.120 | 0.104 | 0.38 |

| Condoms at Home | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.120 | 0.106 | 0.59 |

| Safe/No Sex | 0.545 | 0.547 | 0.540 | 0.547 | 0.93 |

| Panel B: Effects of Receiving an Incentive on Sexual Behavior | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||||||

| All (N=447) | Zero Incentive (N=143) | Medium Incentive (N=148) | High Incentive (N=156) | p-value of joint test | All (N=571) | Zero Incentive (N=194) | Medium Incentive (N=179) | High Incentive (N=198) | p-value of joint test | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|

|

||||||||||

| Any Vaginal Sex | 0.626 | 0.538 | 0.682 | 0.654 | 0.030 | 0.580 | 0.644 | 0.575 | 0.520 | 0.04 |

| Days Vaginal Sex | 1.870 | 1.490 | 1.905 | 2.186 | 0.020 | 1.746 | 1.892 | 1.782 | 1.571 | 0.32 |

| Used Condom | 0.107 | 0.078 | 0.109 | 0.127 | 0.570 | 0.057 | 0.055 | 0.078 | 0.038 | 0.45 |

| Safe/No Sex | 0.432 | 0.497 | 0.392 | 0.410 | 0.160 | 0.450 | 0.392 | 0.458 | 0.500 | 0.10 |

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%

Notes: This table presents means of sexual behavior outcomes by incentive amount. Panel A includes 1,193 HIV negative respondents who participated in the incentives program. Panel B includes those who were interveiewed at Round 4 approximately one week after the money was distributed.

Appendix C

Impact of Amount of Incentive Offer on Reported Sexual Behavior

| HIV Positive (Round 3) | Pregnant (Women) | Any Vaginal Sex | Days of Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Condoms at Home | Safe/No Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|

|

|||||||

| Panel A: All Rounds Pooled | |||||||

| Low Incentive | -- | −0.017 | 0.007 | 0.068 | −0.017 | 0.009 | −0.008 |

| -- | [0.017] | [0.024] | [0.107] | [0.021] | [0.016] | [0.024] | |

| High Incentive | -- | 0.010 | 0.017 | 0.010 | −0.019 | −0.000 | −0.015 |

| --

|

[0.017] | [0.024] | [0.099] | [0.021] | [0.016] | [0.024] | |

| Observations | -- | 1,777 | 3,258 | 3,258 | 1,748 | 3,258 | 3,258 |

| R-squared | -- | 0.037 | 0.095 | 0.064 | 0.089 | 0.045 | 0.087 |

| Panel B: Round 1 | HIV Positive (Round 3) | Pregnant (Women) | Any Vaginal Sex | Days Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Condoms at Home | Safe/No Sex |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|

|

|||||||

| Low Incentive | -- | 0.004 | 0.026 | 0.145 | −0.025 | 0.021 | −0.014 |

| -- | [0.030] | [0.039] | [0.135] | [0.031] | [0.024] | [0.040] | |

| High Incentive | -- | 0.034 | 0.052 | 0.145 | −0.036 | −0.009 | −0.044 |

| -- | [0.029] | [0.036] | [0.134] | [0.028] | [0.025] | [0.034] | |

|

|

|||||||

| Observations | -- | 601 | 1,101 | 1,101 | 621 | 1,101 | 1,101 |

| R-squared | -- | 0.042 | 0.085 | 0.072 | 0.134 | 0.067 | 0.076 |

| Panel C: Round 2 | HIV Positive (Round 3) | Pregnant (Women) | Any Vaginal Sex | Days Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Condoms at Home | Safe/No Sex |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|

|

|||||||

| Low Incentive | -- | −0.024 | −0.023 | −0.030 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.022 |

| -- | [0.027] | [0.035] | [0.153] | [0.036] | [0.022] | [0.039] | |

| High Incentive | -- | 0.010 | 0.000 | −0.092 | −0.025 | −0.016 | −0.016 |

| -- | [0.026] | [0.032] | [0.118] | [0.029] | [0.023] | [0.036] | |

|

|

|||||||

| Observations | -- | 579 | 1,064 | 1,064 | 574 | 1,064 | 1,064 |

| R-squared | -- | 0.040 | 0.102 | 0.077 | 0.124 | 0.058 | 0.107 |

| Panel D: Round 3 | HIV Positive (Round 3) | Pregnant (Women) | Any Vaginal Sex | Days Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Condoms at Home | Safe/No Sex |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|

|

|||||||

| Low Incentive | 0.006 | −0.032 | 0.019 | 0.088 | −0.033 | −0.002 | −0.033 |

| [0.007] | [0.024] | [0.037] | [0.150] | [0.033] | [0.019] | [0.036] | |

| High Incentive | −0.003 | −0.014 | −0.002 | −0.026 | 0.011 | 0.024 | 0.017 |

| [0.005] | [0.027] | [0.034] | [0.139] | [0.031] | [0.021] | [0.033] | |

|

|

|||||||

| Observations | 1,071 | 597 | 1,091 | 1,091 | 552 | 1,091 | 1,091 |

| R-squared | 0.011 | 0.048 | 0.116 | 0.060 | 0.035 | 0.034 | 0.102 |

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%

Note: All columns present OLS regressions. Robust standard errors clustered by individual (Panel A) or village (Panels B, C, and D), in brackets. “Used a condom” is conditional on reported sexual activity. “Safe Sex or No Sex” is equal to one if the respondent abstained from sex or used a condom and zero otherwise. “Vaginal Sex” is a dummy variable equal to one if the respondent reported having had vaginal sex. “Used a Condom” is a dummy variable equal to one if the respondent reported using a condom. Each regression includes controls for whether the respondent is male, married, has some schooling, HIV status at baseline, number of living children, and distric fixed effects. Panel A includes round dummies.

Appendix D

Differential Responses to Incentive Offer

| Panel A: Education | Pregnant (Women) | Any Vaginal Sex | Days Vaginal Sex | Used Condom | Condoms at Home | Safe/No Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|

|

||||||

| Any Incentive | −0.005 | 0.009 | 0.083 | −0.021 | 0.004 | −0.012 |

| [0.026] | [0.044] | [0.124] | [0.023] | [0.024] | [0.046] | |

| Any * Education | 0.003 | 0.004 | −0.060 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| [0.031] | [0.053] | [0.164] | [0.028] | [0.030] | [0.053] | |

| Education | −0.025 | 0.019 | 0.136 | −0.009 | 0.024 | −0.025 |

| [0.026] | [0.045] | [0.156] | [0.026] | [0.029] | [0.048] | |

|

|

||||||

| Observations | 1,777 | 3,258 | 3,258 | 1,748 | 3,258 | 3,258 |

| R-squared | 0.036 | 0.095 | 0.064 | 0.089 | 0.045 | 0.087 |

| Panel B: Income | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|

|

||||||

| Any Incentive | 0.021 | −0.101** | −0.230 | 0.005 | −0.005 | 0.087* |

| [0.026] | [0.043] | [0.199] | [0.044] | [0.026] | [0.045] | |

| Any * Log Income | −0.004 | 0.014** | 0.034 | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.012** |

| [0.003] | [0.006] | [0.024] | [0.006] | [0.003] | [0.006] | |

| Log Income | 0.002 | −0.008 | −0.017 | −0.006 | −0.001 | 0.005 |

| [0.002] | [0.005] | [0.019] | [0.004] | [0.003] | [0.005] | |

|

|

||||||

| Observations | 1,674 | 3,067 | 3,067 | 1,624 | 3,067 | 3,067 |

| R-squared | 0.035 | 0.094 | 0.066 | 0.092 | 0.044 | 0.084 |

| Panel C: Gender | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|

|

||||||

| Any Incentive | -- | −0.004 | −0.068 | −0.031 | −0.003 | −0.005 |

| -- | [0.026] | [0.089] | [0.023] | [0.017] | [0.024] | |

| Any * Male | -- | 0.035 | 0.235 | 0.025 | 0.015 | −0.014 |

| -- | [0.037] | [0.164] | [0.037] | [0.031] | [0.037] | |

| Male | -- | 0.112*** | 0.298** | 0.077** | 0.072*** | −0.089** |

| -- | [0.037] | [0.139] | [0.031] | [0.026] | [0.036] | |

|

|

||||||

| Observations | -- | 3,258 | 3,258 | 1,748 | 3,258 | 3,258 |

| R-squared | -- | 0.095 | 0.065 | 0.089 | 0.045 | 0.087 |

| Panel D: Empowerment (Females only) | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|

|

||||||

| Any Incentive | 0.028 | 0.033 | 0.369 | −0.079 | −0.060 | −0.056 |

| [0.049] | [0.096] | [0.397] | [0.076] | [0.052] | [0.093] | |

| Any * Empowered | −0.071 | −0.081 | −0.904 | 0.126 | 0.121 | 0.114 |

| [0.102] | [0.194] | [0.780] | [0.157] | [0.100] | [0.186] | |

| Empowered | 0.018 | 0.063 | 0.283 | −0.046 | −0.010 | −0.129 |

| [0.084] | [0.171] | [0.722] | [0.115] | [0.083] | [0.155] | |

|

|

||||||

| Observations | 1,675 | 1,677 | 1,677 | 797 | 1,677 | 1,677 |

| R-squared | 0.035 | 0.086 | 0.058 | 0.056 | 0.036 | 0.064 |

significant at 10%;

significant at 5%;

significant at 1%

Note: All columns present OLS regressions. Robust standard errors clustered by individual, in brackets. “Used a condom” is conditional on reported sexual activity. “Safe Sex or No Sex” is equal to one if the respondent abstained from sex or used a condom and zero otherwise. Each regression includes controls for whether the respondent was offered any incentive controlling for whether the respondent is male, married, has some schooling, HIV status at baseline, number of living children, and distric fixed effects.

Footnotes

One exception to this may be male circumcision, however roll-out of these services has been slow.

Because the complete manuscript of the de Walque et al. (2011) study is under embargo, it cannot be cited and/or discussed in detail; at this time, therefore, we limit our discussion of this study to information that is currently publicly available.

It is important to note that our evaluation measures self-reported sexual behavior in response to the incentive. If those who were offered incentives were more likely to overstate safe sexual behavior, our estimates would overstate the true program effects and would thus represent upper-bounds. Since our study documents mostly the absence of any effects of the incentive program, our conclusions are conservative and not sensitive to the most likely form of misreporting in which those who were offered incentives were more likely to overstate safe sexual behavior. On the other hand, other research has documented that self-reported sexual behavior does strongly correlate with HIV status and that use of ACASI computer methods of interviewing may not have large effects on the results (Mensch et al. 2008).

There are, however, a variety of potential non-behavioral reasons for the lack of behavioral change in response to the AIDS epidemic such as lack of information (about how to prevent infection), poverty or high mortality rates from other diseases (ie. lower life-time earnings) or lack of bargaining power (ie. to suggest condom use or abstinence).

See for instance Anglewicz and Kohler (2009); Delavande and Kohler (2009, forthcoming); Fudenberg and Levine (2006); Gul and Pesendorfer (2001, 2004); Laibson (1997) and O’Donoghue and Rabin (1999, 2001). Research on addiction or self-control include Bernheim and Rangel (2004); Gruber and Koszegi (2001) and Gul and Pesendorfer (2007).

While we do not have direct evidence, we perceive that the creditability of the promise of a conditional cash transfer one year in the future was relatively high in our project for several reasons. First, the MDICP project has been interviewing respondents in the study villages since 1998, and in many cases, respondents of the Malawi Incentive Project were themselves or had relatives who have been interviewed by the project since 1998. Moreover, during the one year period relevant for the CCT payments, the respondents were visited three times as part of the collection of sexual diaries that are described in more detail below. These repeated visits reminded respondents of their participation in the Malawi Incentive Project and signaled to the respondents the ongoing commitment of the project to the conditional incentive payments at the end of the study period. This is also related to a paper that finds evidence in an experiment that a large proportion of Malawian farmers are time inconsistent (Giné et al. 2010).

Only married spouses who were both in the MDICP sample were given the chance to have the couples counseling. If both of the spouses agreed to the couple testing, they would both be tested and both learn the HIV results together. If one of the individuals did not consent, then both members of the couple would receive individual counseling, and only learn their own HIV results.

Due to logistical issues, the second round of HIV testing was conducted several months after that, approximately 15 months after the first round of testing.

If the married couple had agreed to the couples HIV testing, they were offered to be enrolled into the couples’ incentive program. All of the respondents who had had individual HIV testing, or those whose couple was away or who refused the couple incentive program, were offered the individual incentive program.

While multiple partnerships may have been one important indicator of risky sexual behavior we do not observe a lot of variation in reported multiple partnerships in the sexual diaries. For example, in the first round of sexual diaries, only 3.7 percent of those who reported having one partner also reported having two. Only 0.4 percent report having more than two partners in that week. The majority of those reporting multiple partners are polygamous men. This may be due to the fact that multiple partnerships are infrequent and we do not capture this very well using the diary method, or that there is underreporting. The interviewers used in the data collection were local enumerators and while there is evidence that “insiders” may increase data quality in Africa (Sana and Weinreb 2008), there may have been some reluctance to report multiple partnerships. For this reason, we do not analyze this variable in this paper.

The majority of the individuals in the sample are married. A subset of the individuals’ spouses are included in the sample. This is by design when the couples counseling was introduced in 2006. However, given that individuals may report differently from each other, or may have extra-marital relationships, we treat each observation as independent.

These power calculations are based on an enrollment of 1,200 individuals in the study, of whom .84 participate in all three sexual diaries, a α = .1, three repeated measures of each sexual behavior with means and standard deviations for the control group as observed in the data, and a correlation of repeated measurements of these sexual behaviors as observed in the data.

The empowerment questions included: “Do you think it is proper for a wife to leave her husband if: He does not support her and the children financially?; He beats her frequently?; He is sexually unfaithful?; She thinks he might be infected with HIV?; He does not allow her to use family planning?; He cannot provide her with children?; He doesn’t sexually satisfy her?”. “Is it acceptable for you to go to: The local market without informing your husband?; The local health center without informing your husband.”. “A woman has the right to refuse sex with her husband when she: Is tired from working hard; Doesn’t feel like it or is not in the mood; During the abstinence period after childbirth; Is no longer attracted to her husband.”. “A woman has the right to refuse unprotected sex with her husband when she: Thinks her husband may have HIV/AIDS; Thinks she may have HIV/AIDS; Doesn’t want to risk getting pregnant”. “If a woman often refuses sex with her husband, is it acceptable for the husband to: Refuse to eat her nsima; Sleep with another sexual partner; Sleep with her by force; Stop providing for her.”.

There were also no differential effects by marital status, or age of the respondent (not shown)

One question is whether there might be large differences in the mean in the control pre-program, round 3 and post-program. Because we do not have baseline sexual diaries in our data, we cannot compare pre-program sexual behavior. However, we can test the average across the rounds in the control group. For each of the dependent variables in Table 4 and 5, there are no significant differences in the average value across round, either pooled, or disaggregated by gender. In Table 6, There are some differences in the average in the control group pre and post receiving incentive money as can be seen with the average values of the control group presented in Table 6.

The relationship between income and HIV has been studied in other settings. For example, research has found a positive correlation between household assets and HIV or early adult mortality (de Walque 2006; Shelton et al. 2005; Yamano and Jayne 2004). Alternatively, wealthier men might have higher returns to safe sex.

Several exceptions include Duflo et al. (2006) who find that Kenyan girls receiving free school uniforms were less likely to become pregnant, Baird et al. (2010) who find that direct payments of secondary school fees lead to significant declines in early marriage, teenage pregnancy, and self-reported sexual activity, and Robinson and Yeh (2009) who find that health shocks lead Kenyan prostitutes to engage in riskier sexual behavior.

It is worth briefly mentioning that to the extent that self-reported sexual behavior may introduce measurement error leading to an attenuation of results–consistent with the results in Tables 4 and 5; the fact that we find effects in the last round help to mitigate the concern that self-reports are dramatically mis-measured or random answers.

Contributor Information

Hans-Peter Kohler, Email: hpkohler@pop.upenn.edu, University of Pennsylvania.

Rebecca Thornton, Email: rebeccal@umich.edu, University of Michigan.

References

- Anglewicz P, Adams J, Obare F, Kohler H-P, Watkins S. The Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project 2004–06: Data collection, data quality and analyses of attrition. Demographic Research. 2009;20(21):503–540. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz P, Kohler H-P. Overestimating HIV infection: The construction and accuracy of subjective probabilities of HIV infection in rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2009;20(6):65–96. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird S, Chirwa E, McIntosh C, Özler B. The short-term impacts of a schooling conditional cash transfer program on the sexual behavior of young women. Health Economics. 2010;19(S1):55–68. doi: 10.1002/hec.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim BD, Rangel B. Addiction and cue-triggered decision processes. American Economic Review. 2004;94(5):1558–1590. doi: 10.1257/0002828043052222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertozzi S, Padian NS, Wegbreit J, DeMaria LM, Feldman B, Gayle H, Gold J, Grant R, Isbell MT. HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 331–370. http://files.dcp2.org/pdf/DCP/DCP18.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Charness G, Gneezy U. Incentives to exercise. Econometrica. 2009;77(3):909–931. [Google Scholar]

- de Janvry A, Finan F, Sadoulet E, Nelson D, Lindert K, de la Briére B, Lanjouw P. Social Protection Discussion Paper 0542. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2005. Brazil’s Bolsa Escola Program: The role of local governance in decentralized implementation. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/SOCIALPROTECTION/Resources/SP-Discussion-papers/Safety-Nets-DP/0542.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- de Janvry A, Sadoulet E. Making conditional cash transfer programs more efficient: Designing for maximum effect of the conditionality. World Bank Economic Review. 2006;20(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- de Walque D. Who gets AIDS and how? The determinants of HIV infection and sexual behaviors in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya and Tanzania. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No 3844. 2006 http://ssrn.com/abstract=922970.

- de Walque D, Dow WH, Nathan R, Medlin CA the RESPECT study team. Evaluating conditional cash transfers to prevent HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in Tanzania. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; Washington, DC. March 31–April 2, 2011; 2011. http://paa2011.princeton.edu/download.aspx?submissionId=112619. [Google Scholar]

- Delavande A, Kohler H-P. Subjective expectations in the context of HIV/AIDS in Malawi. Demographic Research. 2009;20(31):817–874. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]