Abstract

Introduction: DHPEE is a newly synthesized compound by merging the key structural elements in an angiotensin receptor blocker (Telmisartan) with key structural elements in 1,4- dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (Nifedipine). In this study, we examined dual calcium channel blocking and AT1 antagonist activity for DHPEE. Methods: The functional inhibitory characteristics of DHPEE were studied in vitro in rat thoracic aorta preparations precontracted by phenylephrine (1μM) or KCl (80μM) or Ang II in normal or calcium-free solutions. Results: Concentration–dependent significant relaxation was observed in aortic rings precontracted with phenylephrine, KCl or Ang II. The tension increment produced by increasing external calcium was also reduced by DHPEE. DHPEE caused a marked decrease in the maximal contractile response of the vasoactive agents and shifted their concentration-response curves to the right. Conclusion: DHPEE possesses dual characteristics and cause vasorelaxation by blocking the L-type calcium channels and blocking Ang II receptors (AT1) in rat aortic smooth muscle.

Keywords: Angiotensin II, Rat Aorta, DHPEE, Calcium Channel blocker, Angiotensin Receptor blocker

Introduction

The renin–angiotensin system plays an important role in the development and maintenance of hypertension and hypertensive heart disease.1

Angiotensin II (Ang II) as a major component of the renin–angiotensin system is among the potent mediators of vascular contraction and remodeling and stimulates aldosterone secretion. Ang II plays an important role in the pathophysiology of hypertension2 and promotes short- and long-term metabolic and functional changes mostly by activating the type 1 receptors (AT1) located at smooth muscle cells (VSMCs).3,4 AT1 receptor – coupled G – proteins activate PLC which in turn activates IP3 and DAG leading to release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum.5,6

It has been suggested that the increased intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) activates chloride channels causing an efflux of chloride and subsequent depolarization of the cell membrane leading to opening of voltage – gated calcium channels.6-9

To date, many orally available sartans have been developed and are used in the treatment of hypertension and damages associated with diabetes or vascular diseases like atherosclerosis. In particular the good properties of new nonpeptide Ang II antagonists such as losartan have stimulated the design of different congeners.10Ang II receptor blockers have proved to lower blood pressure more effectively11 and they have been more tolerable than other classes of antihypertensives.12

Organic calcium antagonists, known also as calcium channel blockers, are a chemically heterogeneous group of drugs which antagonize calcium–dependent events with varying degrees of potency and specificity.13 Many of these compounds appear to exert their antihypertensive and antianginal actions through inhibition of voltage–dependent L–type calcium channels in cardiovascular system.14

Since 1,4–dihydropiridine (DHP) calcium channel blockers (CCBs) have greater vasodilator selectivity than non–DHP CCBs15 a large number of them has been developed.

Most patients with hypertension require more than a single antihypertensive agent, particularly if they have comorbid diseases.16

Combination therapy of hypertension with separate antihypertensives or a fixed-dose combination offers the potential to decrease adverse effects, lower blood pressure, and obtain target blood pressure more quickly with equivalent or better tolerability than higher-dose monotherapy.

Antihypertensive agents by different mechanism of action may offset adverse reactions from each other.17 Combination therapies of ARBs with CCB which acts through L–type calcium channels have beneficial therapeutic and protective effects on cardiovascular system.18-21

In a recent study It has been suggested that the combination of olmesartan and azelnidipine has advantages over the combination of olmesartan and a thiazide with respect to avoiding hyperuricemia, sympathetic activation, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system stimulation, inflammation, oxidative stress, and increased arterial stiffness in patients with moderate hypertension. These properties may provide cardiovascular protection in addition to the hypotensive effect.22 Fixed-dosed combination regimens consisting of a calcium channel blocker and an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker represent a new addition to the available antihypertensive treatment options.23 An antihypertensive agent with both ARB with CCB properties would be more advantageous than fixed-dosed combinations in saving costs, reducing complexities of drug formulations with equivalent or improved compliance.

Dialkyl 1,4 – dihydro – 2,6 – dimethyl – 4 - [(2' – carboxy biphenyl – 4 – yl)methyl] imidazol – 4 – el ] – 3,5 – pyridindicarboxylate (DHPEE) is a new compound which is synthesized by merging the key structural elements in an ARB (Telmisartan) with key structural elements in 1,4 – dihydropyridine CCB (Nifedipine) in Medicinal Chemistry Department, School of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.18 In this study, for the first time, we examined its dual calcium channel blocking and AT1-antagonist activity on rat isolated aorta (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Chemical structure of DHPEE

Materials and Methods

Functional studies

Wistar rats from either gender weighting 250 – 300 g were used. Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) intraperitoneally and the thoracic aorta was quickly removed, gently cleaned of adhering fat and connective tissues, taking care not to damage the endothelium and cut in rings.

Ring segments (3-5 mm) were mounted between two stainless steel triangle wires in 10 ml organ bath filled with modified Krebs solution under passive tension of 2g for about 1 hour.

The Krebs solution had the following composition (mM): NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2.5, MgSO4 1.2, KH2PO4 1.17, NaHCO3 20 and glucose 11. The rings were maintained at 37°C and gassed with a 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2 mixture (PH = 7.4).

Changes in isometric tension were recorded on a computer-assisted data acquisition system (AD Instrument, Power Lab/4SP, v 6.1.1) with force–displacement transducers (LETICA, Spain) as previously reported.24-26

In all experiments after 1 hour of equilibration period aortic rings were challenged with KCl (80 mM) to assure the good contractile condition of the preparations. During this equilibration period, tissues were washed every 15 min with fresh Krebs solution.26

Evaluation of the vasorelaxant effect of DHPEE

To evaluate the vasorelaxant effect of DHPEE, after 1 h equilibration, aortic rings precontracted using phenylephrine (1 µM) or KCl (80 mM) and once the plateau was obtained, different concentration of DHPEE (0.1-80 µM) was individually added to organ- bath. The percentages of phenylephrine or KCl–induced relaxation of DHPEE were recorded after 40 min incubation.

Effect of DHPEE on dose – response curves to CaCl2

After 60 min equilibration period in the normal Krebs solution, the aortic rings were incubated for 30 min in Ca2+ - free Krebs solution plus 0.1mM EDTA.

After adding KCl (60 mM), dose–response curve to calcium was obtained on control. The same protocol was repeated in the same aortic rings after washing with treatment with DHPEE (0.01, 0.1 and 1µM) for 30 min or nifedipine (0.1 µM) for 20 min.27,28

Effect of DHPEE on dose – response curves to Ang II

After 1 h equilibration period, different concentrations of Ang II (starting at 1 nM) were added to organ–bath in a single dose manner. After adding the latest concentration of Ang II, the aortic rings were washed and recovered to baseline. The same protocol was repeated after incubation with different concentrations of DHPEE (0.001, 0.01 and 0.1µM) for 30 min or losartan (0.01 and 0.1µM) for 15min.29-31

Drugs

Chemicals used were: Nifedipine (Zahravi pharmaceuticals Co, Tabriz – Iran), Losartan (Daru–Pakhsh Pharmaceutical Co, Tehran – Iran) DHPEE (Medicinal Chemistry Department, School of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences) and Ang II (Sigma, USA).

Losartan and Ang II were dissolved in distilled water. Nifedipine and DHP–ethyl ester were dissolved in absolute ethanol. Final bath concentration of ethanol as vehicle was 0.1 % V/V without any significant effect on the CaCl2 and Ang II- induced contractions. All of the solutions were protected from light.

All other reagents were of analytical grade and obtained from Merk KGaA 62471 Damstadt, Germany.

Statistical analysis

The EC50 of the drug required to produce 50% of the maximal response were determined by computer–assisted interactive nonlinear regression analysis (Microsoft Excel 2007).

The maximal response (Emax) produced by CaCl2 and Ang II was expressed as percentage of the maximum response and those by DHPEE, nifedipine and losartan were expressed as the percentage relaxation of the agonist–induced contraction. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Statistical evaluations were performed using paired student's t- test. p< 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

Effect of DHPEE on Phenylephrine or KCl induced contractile responses

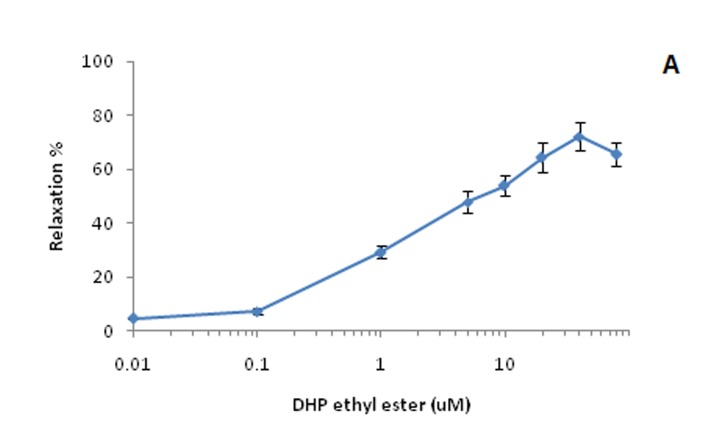

The concentration ranges and drug – tissue contact time were chosen after preliminary experiments, which had shown that each concentration of antagonist tested produced maximal inhibition within the first 40 min of treatment. DHP–ethyl ester reduced KCl–induced contractile responses of aortic rings in a concentration–dependant manner (0.01-40 µM). Beyond this concentration, the relaxation was reduced. This can be related to low solubility of DHPEE in water at high concentrations. Similarly, DHPEE reduced phenylephrine–induced contractile responses in aortic rings in a concentration–dependent manner, but maximum relaxation to DHPEE in of KCl-contracted rings (Emax =72.08 % ± 5.37, EC50=5.76), was significantly higher than the response in phenylephrine-contracted tissues (Emax =46.3 % ± 3.29, EC50 = 6.88) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Vasorelaxant effect of DHPEE on rat thoracic aorta rings precontracted with A: KCl (80 mM) and B: Phenylephrine (1 µM). Data are expressed as Mean±SEM, n=6.

A.

B.

Effects of DHPEE on dose – response curve of CaCl2

CaCl2 induced a concentration – dependent contractile effect on K+ - depolarized smooth muscle. Preincubation of the k+-depolarized tissues with DHPEE or nifedipine resulted in a non parallel shift to the right of the calcium dose response curves (Figure 2). In addition, DHPEE induced a concentration–dependant and significant reduction in the maximal contraction to CaCl2 (Table 1).

Figure 2. The inhibitory action of A: DHPEE [ 0(♦), 0.01(■), 0.1(▲), 1(ӿ)µM] and B: nifedipine [0(♦), 0.1(■) µM ] on the contractile response of rat isolated aorta induced CaCl2 in Ca- free Krebs' solution. Data are expressed as Mean±SEM, n=6.

A.

B.

Table 1. Inhibitory effects of DHPEE on the CaCl2 induced .

| CaCl2 | ||

| EC50(µM) | EMax± SEM | |

| Control | 2.02 | 100 |

| DHPEE 0.01µM | 2.67 | 71.43± 7.06* |

| DHPEE 0.1 µM | 2.86 | 59.36± 6.59*** |

| DHPEE 1 µM | 2.34 | 40.34± 7.94*** |

| Nifedipine 0.1 µM | 4.68 | 24.73± 5.71*** |

Emax and EC50 from rat thoracic aorta rings concentration-response curve to CaCl2, in the absence and presence of DHPEE or nifedipine, n=6.

(*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001)

Effect of DHPEE on dose–response curve of Ang II

The effect of the different concentrations of DHPEE and losartan on Ang II–evoked contractile responses in rat aortic strips is shown in figure 3 and table 2. Increasing concentrations of DHPEE and 0.1µM of losartan resulted in a progressive and significant reduction in the maximal response to Ang II. The maximal response to Ang II was not significantly changed by losartan 0.01 µM. Preincubation with losartan (0.01µM) resulted in a parallel right ward shift of the concentration–response curve of Ang II. However, the rightward shift with DHPEE or higher concentration of losartan (0.1µM) was in nonparallel fashion.

Figure 3. The inhibitory action of A: DHPEE [ 0(♦), 0.001(■), 0.01(▲),0.1(ӿ) µM] and B: Losartan [0(♦), 0.01(■), 0.1(▲) µM ] on the contractile response of rat isolated aorta induced by Ang II. Data are expressed as Mean±SEM, n=6.

A.

B.

Table 2. Inhibitory effects of DHPEE on the Ang II induced contraction .

| Ang II | ||

| EC50(µM) | EMax± SEM | |

| Control | 0.158 | 100 |

| Losartan 0.01 µM | 0.258 | 89.58 ± 1.59 |

| Losartan 0.1 µM | 0.303 | 47.8 ± 7.32** |

| DHPEE 0.001µM | 0.143 | 55.48 ± 12.12** |

| DHPEE 0.01 µM | 0.126 | 47.56 ± 5.36 *** |

| DHPEE 0.1µM | 0.175 | 26.76 ± 3.2 *** |

Emax and EC50 to Ang II contractile response in rat thoracic aorta rings, in the absence and presence of DHPEE or Losartan, n=6.

(*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001)

Discussion

The present study has demonstrated, for the first time, vasorelaxant effects of newly synthesized DHPEE and its dual mechanism of action. This study showed that DHPEE acts in aortic rings producing a concentration–dependent depressant effect on KCl and Phenylephrine–induced contractions. Our experiments showed that preincubation with DHPEE could effectively antagonize, in a concentration-dependent manner, Ca2+-induced contractions suggesting that DHPEE reduced Ca2+ influx through voltage-operated Ca2+ channels in the isolated aortic smooth muscle. These observations are consistent with reports suggesting that other similar compounds may act as a calcium antagonist through L-type Ca2+ channels.10 Smooth muscle contracts in response to the activation of voltage–dependent and receptor–operated Ca2+ channels.32,33

Since DHPEE inhibitory effects was similar to those elicited by Ca2+ channel blockers, we compared its antagonist effect to the one produced by nifedipine, a known selective inhibitor of the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker. In different types of smooth muscle, Ca2+ channel blockers strongly inhibit the high K+-induced contraction by blocking L-type Ca2+ channels. DHPEE, like nifedipine, inhibited high K+-induced contraction in rat aortic smooth muscle suggesting that it may block voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. However, influx of Ca2+ through L-type Ca2+ channels activation is not the only source to increase intracellular calcium concentration in smooth muscle cells; it might be increased due to Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and/or Ca2+ influx through non-L-type Ca2+ channels.34,35In the present study, DHPEE inhibited either phenylephrine or KCl– induced contractions with more inhibitory effect on KCl–evoked contraction. These observations suggest that DHPEE might interfere with both voltage-dependent and receptor–operated Ca2+ channels reducing the Ca2+ influx and consequently, opposing contraction. It has been reported that contractions induced by α1-adrenoceptor are less sensitive to Ca2+ channel blockers than is the high K+-induced contraction.36

Our experiments showed that contractile responses of rat aortic rings to CaCl2 in Ca2+- free medium containing KCl were inhibited by DHPEE, suggesting that DHPEE reduced Ca2+ influx through voltage–operated Ca2+ channels in the isolated aortic smooth muscle (Figure 2). This effect was very similar to the effect of produced by nifedipine as a prototype of L-type Ca2+ channel blocker. Taken together, it seems that the inhibitory effect of DHPEE on voltage–dependent Ca2+ channels is more potent than receptor–operated Ca2+ channels (Figure 1).

Dimethyl 4-[2-butyl-1-(2’-carboxy biphenyl-4-yl) methylimidazol-4-yl]-1, 4-dihydro-2, 6-dimethylpyridine-3, 5-dicarboxylate (5a), is synthesized by merging the structural key elements of nifedipine and losartan and is structurally very similar to DHPEE. It has been shown that 5a, like DHPEE, inhibited the maximum contractile response to CaCl2 in rat aortic rings and also, this effect was nearly the same as nifedipine- induced effect.10

In Ca2+ free solution, in addition to rightward shift in concentration–response curve for CaCl2, DHPEE depressed the maximum response to calcium, which suggests blocking the voltage dependant Ca2+ channels by DHPEE seems insurmountable. Nifedipine in a similar profile of effect reduced the maximum contractile response and also made a rightward shift in concentration–response curve of CaCl2. This finding is in accordance with the results of other similar studies.13,28

Another aspect examined in the present study was the inhibitory effect of DHPEE on angiotensin AT1–receptors at aortic smooth muscle tissue. Stimulating AT1 receptors in vascular smooth muscle by Ang II produces potent vasoconstrictor response by increasing intracellular calcium from two main pathways: 1-influx through voltage-dependent L-type calcium channels and 2- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated calcium mobilization from intracellular sources.37,38

Our experiments showed that contractile responses of rat aortic rings to Ang II were inhibited by DHPEE or losartan in a similar pattern (Figure 3). A compound structurally very similar to DHPEE, Diethyl 4-[2-butyl-1-(2’-carboxy biphenyl-4-yl) methylimidazol-4-yl]-1, 4-dihydro-2,6-dimethylpyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (5b) was synthesized recently, by merging the structural key elements of nifedipine and losartan. It has been shown that 5b inhibited the contractile response to single dose of Ang II in rat aortic ring.10 These results are in agreement with the results of our study.

Results from a previous study indicate that only up to one-half of the Ang II-induced constriction in renal blood vessels is mediated by voltage-dependent L-type calcium channels responsive to the dihydropyridine, nifedipine. Nifedipine exerted maximum inhibition by blocking 50% of the peak Ang II response. The remaining 50% of the vasoconstriction elicited by Ang II was mediated by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-mediated calcium mobilization from intracellular sources. Heparin or TMB-8 was employed to evaluate intracellular calcium mobilization, and co-administered with Ang II. Each agent produced dose-dependent inhibition of up to 50% of the maximum vasoconstriction produced by Ang II. From these results it has been concluded that two distinct mechanisms calcium mobilization and calcium entry signaling pathways that are of equal importance are involved in Ang II activation of AT1 receptors to trigger vasoconstriction.37 In a recent study in rat aortic smooth muscle the contribution of L-type calcium channels in Ang II induced vasoconstriction has been estimated at maximum 50% and was evaluated by a high (20 µM) concentration of nifedipine.38

In the present study DHPEE caused a rightward shift in concentration–response curve of Ang II which shows, blocking the effects of Ang II is competitive and insurmountable , like telmisartan (a selective long acting AT1 – receptor blocker ).39,40Then, we compared the Ang II blocking activity of DHPEE with losartan, as a selective AT1–receptor blocker. Losartan caused a rightward shift in concentration–response curve of Ang II without significant reduction in maximal response to Ang II, which shows losartan is a competitive and surmountable antagonist of AT1–receptors.29 However, higher concentration of losartan, like DHPEE, reduced the maximum contractile response to Ang II. Ang II contracts the smooth muscle by increasing the [Ca2+]i through different ways.21,37,38 DHPEE inhibits Ang II-induced contraction. The question is how it can be proved that this inhibitory effect is produced by blocking AT1 receptors and not blocking L-type calcium channels. It is obvious from figure 3 and table 2 that DHPEE could inhibit Ang II induced contraction much more than 50%, on the other hand the maximum participation of L-type calcium channel pathway in Ang II- induced vasoconstriction is 50%. In addition, DHPEE inhibitory effect is more similar to losartan effect; however, it seems more potent than losartan.

These results may suggest that DHPEE make vasorelaxation at least by two mechanisms: 1) blocking L-type calcium channels and 2) blocking AT1 receptors in aortic vascular smooth muscle. Complementary studies including receptor- and channel-bindings will give more insight to the exact mechanism(s) of action of DHPEE in vascular smooth muscle tissue. The dual mechanisms of DHPEE in rat aortic rings demonstrated in this study may prove particularly important in future vasorelaxing therapy in cardiovascular diseases.

Ethical issues

Rats were handled with care and treated in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guidelines and the experimental procedure was approved by the Ethical Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank Pharmaceutical Research Network, Iranian Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical Education, and Drug Applied Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for financial support of the project. The results presented in this work are from Pharm D. thesis of F. Ebrahimi.

References

- 1.Wolfgang W, Michael E, Jacobus JACOBUS, Ca CA, Joachim S, Ulrich B. A review on Telmisartan:A novel , Long acting Angiotensin II – receptor Antagonist. Cardiovas Drug Rev. 2000;18:127–154. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunner HR, Nussberger J, Wäber B. Angiotensin Antagonists. In: Robertson JIS, Nicholls MG, Editors.The Renin Angiotensin System. London: Gower Medical Publishing, 1993; 86(14): p: 1-86.

- 3.Frank GD, Eguchi S. Activation of tyrosine kinases by reactive oxygen species in vascular smooth muscle cells: significance and involvement of egf receptor transactivation by angiotensin II. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5(14):771–780. doi: 10.1089/152308603770380070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Failli P, Alfaran C, Franchi S. et al. Losartan counteracts the hyper – reactivity to angiotensin II and rocki over – activation in aorta isolated from streptozotocin – injected diabetic rats. Cardiovascular diabetology. 2009;8:32–45. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navar LG, Inscho EW, Majid SA, Imig JD, Harrison – BERNARD, Mitchell KD. Paracrine regulation of the renal microcirculation. Physiol rev. 1996;76:425–536. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmines PK. Segment – specific effect of chloride channel blockade on rat renal arteriolar contractile responses to angiotensin ii. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:90–94. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(94)00170-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen BL, Skott O. Blockade of chloride channels by dids stimulates renin release and inhibits contraction of afferent arterioles. Am J physiol. 1996;271:f718–727. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.5.F718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the ca2+ - activated cl – conductance in smooth muscle. Am J physiol. 2005;271:c435–545. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steendahl J, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Sorensen CM, Salomonsson M. Effects of chloride channel blockers on rat renal vascular responses to angiotensin II and norepinephrine. Am J physiol renal physiol. 2004;286:f323–330. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00017.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadizadeh F, Imenshahi M, Esmaili P, Taghiabedi M. Synthesis and effects of noval dihyropyridines as dual calcium channel blocker and angiotensin antagonist on isolated rat aorta. Iranian journal of basic medicinal sciences. 2010;13:p195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 11.European society of hypertension-european society of cardiology guidelines committee. 2003 european society of hypertension-european society of cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J hypertens 2003; 21: 1011-1053. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Singh RK, Barker S. Progress in the development of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. Curr opin investig drugs. 2005;6:269–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Triggle DJ. The 1,4-dihydropyridine nucleus: a pharmacophoric template part 1. Actions at ion channels. Mini rev med chem. 2003;3:215–23. doi: 10.2174/1389557033488141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godfriend T, Miller R, Wibo M. Calcium antagonism and calcium entry blockade. Pharmacol rev. 1986;38:321–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taira N. Differences in cardiovascular profile among calcium antagonists. Am J cardiol. 1987;59:24B–29B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank J. Managing hypertension using combination therapy. Am fam physician. 2008;77:1279–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mancia G, Seravalle G, Grassi G. Tolerability and treatment compliance with angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shahbazi-mojarrad J, Nazemiyeh H, Kaviani F. Synthesis and regioselective hydrolysis of noval diallcyl 4 – imidazolyl – 1,4 – dihydropyridine – 3,5 – dicarboxylate as potential dual acting angiotensin II inhibitor and calcium channel blockers. J iran chem soc. 2010;7:171–179. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia – li WV, Yin W, Gheng J, Zhao YY. Calcium channel blocking activity of calycosin, a major active component of astragali radix, on rat aorta. Acta pharmacologica sinica. 2006;27:1007–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo XZ, Shi L, Wang R, Liu XX, Li BG, Lu XX. Synthesis and biological activities of novel nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonists based on benzimidazole derivatives bearing a heterocyclic ring. Bioorg med chem. 2008;16:10301–10310. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toda N, Ayajiki K, Okamura T. Interaction of endothelial nitric oxide and angiotensin in the circulation. Pharmacol rev. 2007;59:54–87. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishimitsu T, Numabe A, Masuda T. et al. Angiotensin-ii receptor antagonist combined with calcium channel blocker or diuretic for essential hypertension. Hypertens res. 2009;32:962–968. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakris GL. Combined therapy with a calcium channel blocker and an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker. J clin hypertens (greenwich) 2008;10:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.08029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babaei H, Sadeghpour O, Nahar L. et al. Antioxidant and vasorelaxant activities of flavonoids from amygdalus lycioides var. horrid. Turkish journal of biological sciences. 2008;32:203–208. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azarmi Y, Mohammdi A, Babaei H. Role of endothelium on relaxant effect of geraniol in isolated rat aorta. Pharmaceutical sciences. 2009;14:311–319. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babaei H, Azarmi Y. 17β-estradiol inhibits calcium dependent and independent contractions in isolated human saphenous vein. Steroids. 2008;73:844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salomonsson M, Sorensen CM, Arend shorts WJ, Steendahl J, Holstein– rathlou NH. Calcium handling in afferent arterioles. Acta physiol scand. 2004;181:421–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beigly S, Ghiaee S, Ebrahimi SA, Mahmoudian M. Effects of mebudipine and dibudipine , two new calcium channel blocker , on guinea – pig isolated common bile duct. Acta physiologica hungarica. 2004;91:111–118. doi: 10.1556/APhysiol.91.2004.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Failli P, Alfarano C, Franchi– micheli S, Mannucci E, Cerbai E. Losartan counteracts the hyper – reactivity to angiotensin II and roki over – activation in aortas isolated from streptozocin – injected diabetic rats. J cardiovascular diabetology. 2009;8:32–45. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arendshorst WJ, Brann storm K, Ruan X. Actions of angiotensin II on the renal microvasculature. J am soc nephrol. 1999;10:s149–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inone K, Nishimura H, Kubota J, Kitaura Y. Nitric oxide mediates inhibitory effect of losartan on angiotensin-induced contractions in hamster but not rat aorta. J renin angiotensin aldostrone syst. 2000;1:180–3. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2000.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webb RC. Smooth muscle contraction and relaxation. Adv physiol educ. 2003;27:201–206. doi: 10.1152/advan.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karaki H, Ozaki H, Hori M, Mitsui-saito M, Amano KI, Harada KI. Calcium movements, distribution, and functions in smooth muscle. Pharmacol rev. 1997;49:157–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savineau JP, Marthan R. Cytosolic Calcium Oscillations in Smooth Muscle Cells. News physiol sci. 2000;15:50–55. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benham CD, Bolton TB, Lang RJ, Takewaki T. Calcium activated potassium channels in single smooth muscle cells of rabbit jejunum and guinea-pig mesenteric artery. J physiol. 1986;371:45–67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karaki H, Ozaki H, Hori M. et al. Calcium movements, distribution, and functions in smooth muscle. Pharmacol rev. 1997;49:157–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruan X, Arendshorst WJ. Calcium entry and mobilization signaling pathways in ang ii-induced renal vasoconstriction in vivo. Am J physiol. 1996;270:f398–f405. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.270.3.F398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hun DO K, Kim MS, Kim JH. et al. Angiotensin ii-induced aortic ring constriction is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/l-type calcium channel signaling pathway. Experimental and molecular medicine. 2009;41:569–576. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.8.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motohiko C, Tsoyoshi O, Naoyoki H, Yoichiro N, Hisashi S. Pharmacological and clinical profile of telmisartan, a celective angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker. Nipponyakurigaku zassi. 2004;124:31–39. doi: 10.1254/fpj.124.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolfgang W, Michael E, Jacobus CA, Joachim S, Ulrich B, Thomas E. A review on telmisartan: a novel , long acting angiotensin II – receptor antagonist . Cardiovascular drug reviews. 2009;18:127–154. [Google Scholar]