Abstract

Objective

Group IIa secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2 IIa) plays a role in the malignant potential of several epithelial cancers. Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) regulates cancer cell growth and is modulated by phospholipase activity in many cancer cells. We hypothesized that knockdown of sPLA2 in lung cancer cells would reduce cell proliferation and NF-κB activity in vitro and attenuate tumor growth in vivo.

Methods

Two human non–small cell lung cancer cell lines (A549 and H358) were transduced with short hairpin RNA targeting sPLA2 group IIa. Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and immunoblotting confirmed knockdown of sPLA2 IIa messenger RNA and protein, respectively. Cell proliferation was evaluated by the 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine DNA labeling assay. NF-κB phosphorylation was assayed by western blot. 1 × 106 of A549 or A549 sPLA2 knockdown cells were injected into the left flanks of nude mice (aged 6 to 8 weeks). Tumors were followed for 23 days, then removed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, stained with Ki-67, and analyzed for sPLA2 IIa messenger RNA expression.

Results

sPLA2 knockdown reduced NF-κB phosphorylation and tumor growth in vivo. A549 wild-type tumors grew twice as fast as knockdown tumors. Ki-67 staining was more prominent throughout the wild-type tumors compared with knockdown tumors. Explanted knockdown tumors maintained lower sPLA2 levels compared with wild-type, confirmed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.

Conclusions

Knockdown of sPLA2 IIa suppresses lung cancer growth in part by attenuating NF-κB activity. These findings justify further investigation into the cellular mechanisms of sPLA2 in lung cancer and its potential role as a therapeutic target.

Group IIa secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2 IIa) has recently come to light as an important growth-regulating molecule in several malignancies, including esophageal, prostate, and lung cancer.1-4 We previously demonstrated that inhibition of group IIa sPLA2 decreased intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) associated invasion of lung cancer cells in vitro4; however, the role of the enzyme in lung cancer cell growth has yet to be fully explored.

Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzymes catalyze arachidonic acid release from cell membranes, a rate-limiting step in the pathway leading to the production of tumor-stimulating eicosanoids such as prostaglandins.5-7 PLA2 activity is upregulated in some lung cancers8 and there is decreased lung tumor formation in PLA2 knockout mice.9 Within the family of PLA2 enzymes is the subgroup of secretory PLA2s (sPLA2s). sPLA2 IIa is secreted by a number of cell-types, including epithelial cells of the human airway.10 In addition to its phospholipase enzymatic activity, sPLA2 IIa has been reported to signal as a ligand through receptors that modulate cancer cell proliferation, including the epidermal growth factor receptor, leading to downstream activation of AKT and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2 pathways.11,12 Paracrine interaction between sPLA2 IIa and human lung macrophages also results in the release of growth factors that promote proliferation and angiogenesis.13

Nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) transcription factors facilitate cell growth by stimulating proliferation genes. In cancer cells, breakdown of NF-κB feedback loops or constitutive activation of NF-κB leads to increased proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis.14 NF-κB target genes include components of the arachidonic acid pathway15 as well as proteins that increase the transcription of growth factors.16 Evidence suggests that sPLA2 IIa modulates NF-κB, as ICAM-1 and sPLA2 IIa, both NF-κB target genes, are downregulated when sPLA2 IIa is inhibited.3,4,12

We hypothesize that the knockdown of sPLA2 in lung cancer cells will reduce cell proliferation and that this effect will correlate with decreased NF-κB activity. Furthermore, we propose sPLA2 knockdown in lung cancer cells will attenuate tumor growth in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Reagents

A549 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va). H358 cells were a gift from Kim O’Neill, PhD (Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah). Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 5% carbon dioxide using Ham’s F-12 media (Cellgro, Manassas, Va) or Roswell Park Memorial Institute Media 1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), respectively, with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Mo) was used to induce NF-κB activation. It was dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and used at a concentration of 20 ng/mL. Antibodies for phosphorylated and total NF-κB and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc (Beverly, Mass). Antibody for sPLA2 IIa was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, Mass).

Short-Hairpin RNA (shRNA) Vectors

pLKO.1 puro lentiviral vectors containing non-targeted shRNA and 4 distinct shRNA sequences targeting sPLA2 IIa were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The sequences and preparation of infectious lentiviral constructs are the same as previously described.2

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Cells were plated in 12-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 in full media for 24 hours, then serum-starved (0.5% FBS) for 24 hours before lysis. Xenograft tumors stabilized in RNAlater (Qiagen, Germantown, Md) were disrupted by sonication for RNA preparation. Preparation of RNA was performed using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA was synthesized using Bio-Rad iScript (Hercules, Calif). RT-PCR was performed using Applied Biosystems Sybr Green Master Mix (Carlsbad, Calif). The primer sequences used are as follows: sPLA2 IIa (forward), CCC-TCC-TAC-TGT-TGG-CAG-TGAT; sPLA2 IIa (reverse), CCT-GTC-GTC-AAC-TTG-ATC-ATT-CTG; glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (forward), CCT-GCA-CCA-CCAACT-GCT-TAG; and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (reverse), TGA-GTC-CTT-CCA-CGA-TAC-CAA. Denaturation (95°C for 15 seconds), annealing (52°C for 30 seconds), and elongation (72°C for 30 seconds) were repeated for 40 cycles, flanked by a 10-minute denaturation and 5-minute elongation step. Data was analyzed by the delta delta cycle threshold method.

Western Blotting

Cells were plated on 6-well plates at a density of 3 × 106 in full media for 24 hours, then serum-starved (0.5% FBS) for 24 hours, then treated. Cells were stimulated with or without TNF-α (20 ng/mL) for 4 hours, then lysed with Laemelli buffer under reducing conditions. Time trials with TNF-α identified sustained changes in NF-κB activation at this time point (data not shown). Proteins were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis techniques and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk in 1 × PBS, 0.1% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich). Primary antibodies were dissolved in 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 × PBS, 0.1% Tween-20. Secondary antibodies were prepared in 5% nonfat milk in 1 × PBS, 0.1% Tween-20. The protein of interest was developed using Pierce ECL Chemiluminescent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, Rockford, Ill). Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ Software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md).

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated by the 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine DNA labeling assay according to manufacturer instructions (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind).

Xenograft Experiment

All xenograft experiments were performed under a protocol approved by the University of Colorado Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male nude mice aged 6 weeks were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, Ind) and quarantined for 2 weeks. At age 8 weeks the mice were injected into their left flanks with 1 × 106 cells in 100 μL PBS. Flank tumors were measured every 2 to 3 days using digital calipers and volume was calculated by multiplying height × length × width. Xenograft tumors were removed en bloc and a portion from each tumor was preserved in 4% formalin in PBS and RNAlater. RT-PCR of tumor tissue homogenate was used to examine sPLA2 IIa messenger RNA (mRNA) as described above. Tumors preserved in formalin were paraffin embedded; cut onto slides; and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and for Ki-67. Histology was reviewed by a pathologist blinded to the study.

Statistical Analysis

All data distributions were inspected before statistical analysis. Student t test was performed for 2 group comparisons, and analysis of variance test was performed when comparing 3 or more groups. No multiple comparison was conducted. StatView V5.0 (1998; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Knockdown of sPLA2 IIa in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells

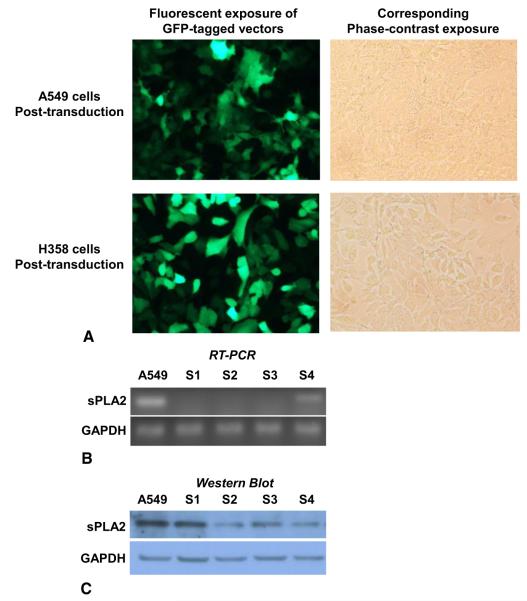

A549 and H358 cells were stably transduced with green fluorescent protein-tagged lentiviral vector particles to confirm efficacy of technique and optimal concentration of particles for transduction (Figure 1, A). Cells were then transduced with lentiviral particles containing shRNA for sPLA2 IIa, or nontargeted shRNA as a control. Selection for transduced cells was with puromycin antibiotic. A kill curve was performed in both cell lines to determine a puromycin concentration of 2 μg/mL for selection (data not shown). Four distinct short hairpin sequences targeting sPLA2 IIa were used and examined for knockdown of sPLA2 IIa both mRNA and protein expression. RT-PCR confirmed decreased mRNA with all sequences, from S1 to S4 (Figure 1, B). Western blot for sPLA2 IIa revealed sequence S2 resulted in the most robust knockdown of protein expression (Figure 1, C). Similar results were obtained in H358 cells, although only data for A549 cells is shown. All subsequent experiments used A549 and H358 cells transduced with sequence S2 shRNA targeting sPLA2 IIa (A549 S2, H358 S2), or nontargeted shRNA (A549 NT, H358 NT), compared with nontransduced wild-type A549 or H358 cells.

FIGURE 1.

Short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequence S2 obtains most robust knockdown of secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) group IIa messenger RNA and protein. A549 and H358 cells were stably transduced with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged lentiviral vector particles, (A) to determine the optimal conditions for transduction, before transducing cells with vector particles containing nontargeted shRNA as a control, or shRNA targeting sPLA2 IIa. Growth selection for transduced cells was with puromycin. Four distinct shRNA sequences (S1 to S4) targeting group IIa sPLA2 were used to create 4 different knockdown cell lines. B, Knockdown was confirmed by messenger RNA and (C) protein analysis. The most robust knockdown in protein was with sequence S2. RT-PCR, Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

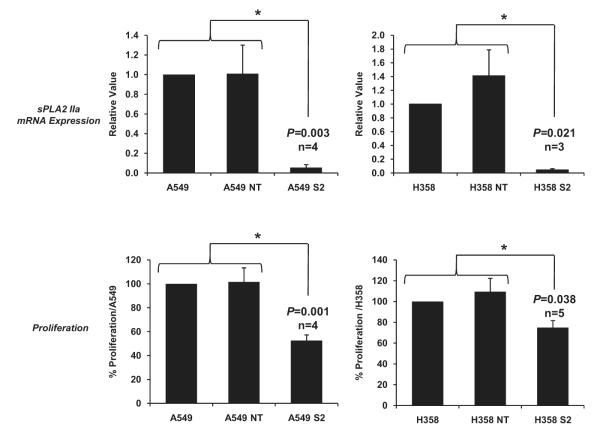

sPLA2 IIa Knockdown Decreases Proliferation in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells

Stable knockdown of sPLA2 IIa mRNA compared with both wild-type controls and nontargeted controls was confirmed over several cell passages using RT-PCR (Figure 2, top panels). Proliferation studies using the 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine assay were performed with the same passages of cells. Results showed a stable reduction by approximately 40% to 50% in the growth rate of both A549 and H358 knockdown cells compared with both control groups (Figure 2, bottom panels). This is consistent with our finding during cell culture that double the concentration of S2 cells compared with nontargeted or wild-type cells were required for the cells to reach confluence at the same time.

FIGURE 2.

Secretory phospholipase A2 group-IIa (sPLA2 IIa) knockdown is stable over several cell passages with corresponding persistent decrease in growth rate of lung cancer cells. Top panels, Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction confirms decreased messenger RNA (mRNA) over several cell passages 1 through 7. Bottom panels, Analysis of proliferation using the same cell passages 1 through 7 shows a stable reduction in the growth rate of both A549 and H358 knockdown cells. Controls for the experiments are wild-type cells and vector controls (NT). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean; n = 3-5 performed in triplicate. *P < .05.

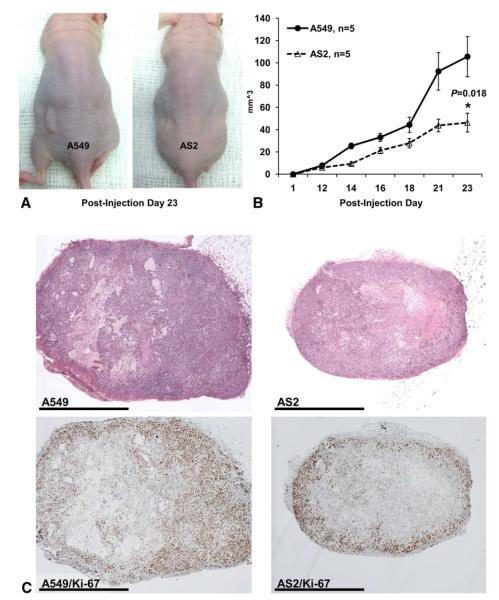

sPLA2 IIa Knockdown Decreases NF-κB Activity

We have previously demonstrated that pharmacologic sPLA2 IIa inhibition decreases NF-κB activity leading to apoptosis in non–small cell lung cancer cells.17 Results from knockdown experiments are similar, because NF-κB phosphorylation in S2 cells is significantly decreased compared with nontargeted or wild-type cells (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Secretory phospholipase A2 group IIa (sPLA2 IIa) knockdown decreases nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) induces NF-κB phosphorylation in A549 cells, vector control cells (ANT) and knockdown cells (AS2), though significantly less in the knockdown cells. Representative western blot of a single experiment is shown with a graph of densitometric analysis of cumulative experiments below (mean ± standard error of the mean; n = 5 per group). Pharmacologic sPLA2 IIa inhibition in lung cancer cells results in a similar decrease in NF-κB phosphorylation (data not shown). *P < .05.

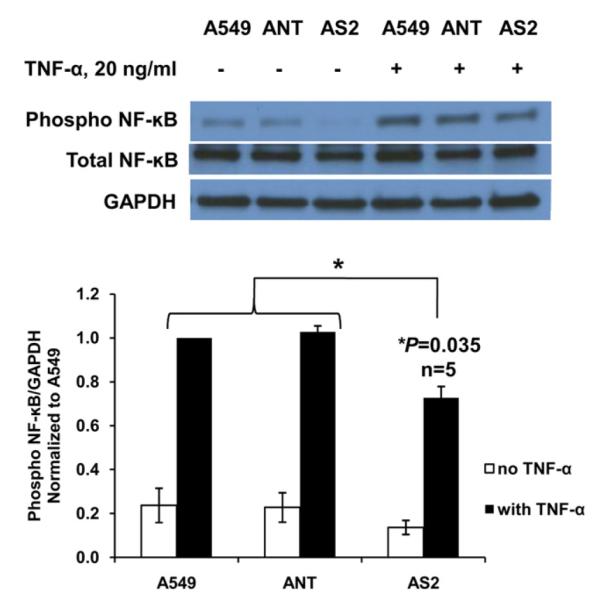

sPLA2 IIa Knockdown Decreases Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Growth In Vivo

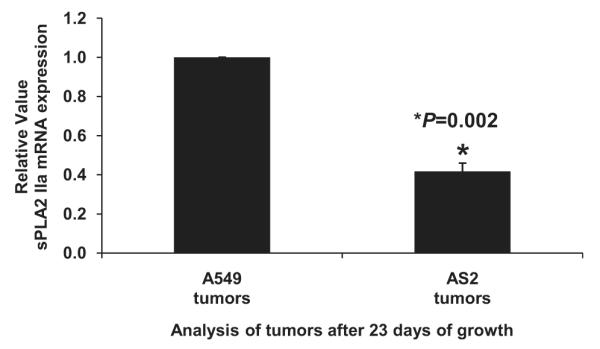

Xenografts of AS2 cells grew significantly slower than wild-type cells (Figure 4, A and B), with wild-type tumors growing to double the volume of knockdown tumors at Postinjection Day 23. Histology from tumors revealed large areas of necrosis characteristic of rapid growth (Figure 4, C). Tumors were also stained with Ki-67, a marker of proliferation. Wild-type tumors had more Ki-67 staining and the location of the staining was throughout the tumor, compared with knockdown tumors where the staining was more visible at the periphery. Analysis of sPLA2 mRNA expression in xenograft tumors confirmed persistent decrease in sPLA2 mRNA in knockdown tumors compared with wild-type tumors (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Secretory phospholipase A2 group IIa knockdown decreases lung cancer cell growth in vivo. A549 and knockdown cells were injected into the left flanks for nude mice and tumor size was serially measured until postinjection day 23. A, Representative photograph of xenograft tumors in situ demonstrating increased A549 tumor size compared with the knockdown tumors. B, Volume of the tumors over time shows significant growth retardation in the knockdown cells (AS2) compared with A549 cells (mean ± standard error of the mean; n = 5) per group. C, Representative histology from knockdown and wild-type tumors exhibit large areas of necrosis representative of fast growth. Wild-type tumors demonstrate increased Ki-67 staining in the compared with more peripheral and less concentrated staining in the knockdown tumors.

FIGURE 5.

Secretory phospholipase A2 group IIa (sPLA2 IIa) messenger RNA (mRNA) remains decreased in knockdown tumors compared with wild-type tumors. Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction of tumor homogenates shows that wild-type tumors had more than double the amount of sPLA2 IIa mRNA compared with knockdown tumors. Average of ΔΔCt for all 5 knockdown tumors was compared with the average of ΔΔCt for all 5 wild-type tumors. Results presented as mean ± standard error of the mean; n = 3 performed in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

Ours is the first study that demonstrates decreased tumor growth in vivo with knockdown of sPLA2 IIa mRNA. These data support a role for sPLA2 IIa in the growth of non–small cell lung cancer and bolster evidence for its relevance as a therapeutic target. Previous studies have reported antimitogenic effects of sPLA2 IIa pharmacologic inhibition and our results using RNA interference support those findings. These data are compelling from both a mechanistic and therapeutic perspective. RNA interference is a potential therapeutic tool. Delivering small interfering RNAs to solid tumors has been reported via intratumoral injection,18 as well as via intravenous delivery. A recent study19 showed that systemically administered small interfering RNA nanoparticles successfully target human cancer cells and reduce target protein levels in tumor tissue. Given that short hairpin knockdown of sPLA2 IIa mRNA slows tumor growth, targeted RNA interference of sPLA2 IIa may have a therapeutic application in the treatment of lung cancer.

We recently examined the relationship between sPLA2 IIa inhibition and cell survival signaling associated with p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2 pathways, AKT, and NF-κB activity in lung cancer cells.17 The results demonstrated a dominant link between NF-κB, sPLA2 IIa, and cell viability. Our study shows that knockdown of sPLA2 IIa decreases NF-κB activity, further supporting the hypothesis of a role for sPLA2 IIa and NF-κB interaction that slows tumor growth.

These data suggest not only potential for sPLA2 IIa as a therapeutic target, but also several mechanisms that can be examined to better understand the unique role of sPLA2 IIa in lung tumor growth. We have thus far examined only growth factor-independent mitogenic signaling, but cancer cells can acquire the capability to sustain proliferative signaling by producing growth factors as well as corresponding growth factor receptors.20 Targeting sPLA2 IIa may exploit its relationship with NF-κB because NF-κB target genes include transcription factors for a number of growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor, which have been linked to promoting cancer cell growth, tumor stroma development, and angiogenesis.20-22

Phospholipase enzymes catalyze the first rate-limiting step in the production of eicosanoids. In lung cancer specifically, eicosanoids have been shown to promote tumor growth.5-7 sPLA2 IIa inhibition may modulate eicosanoid production in lung cancer cells. Future research aims include eicosanoid-dependent versus eicosanoid-independent mechanisms of growth mediated by sPLA2 IIa.

Another hallmark of cancer are its activating mechanisms of invasion and metastasis.23 Previous work has shown that pharmacologic inhibition of sPLA2 IIA reduces ICAM-1 associated invasion in vitro.4 On review of the histology, intravascular invasion was noted in the wild-type tumors but not in the knockdown tumors. Further studies will better address the role of sPLA2 IIa in metastatic disease in vivo.

Our study has several limitations. We compared wild-type and sPLA2 knockdown tumor growth without comparing these to a vector (ie, nontargeted) control group. Expanding the in vivo studies to include multiple cell lines and vector controls are goals for future studies. After 3 weeks of growth the knockdown tumors had persistent low levels of sPLA2 mRNA and peripheral Ki-67 staining. We were unable to detect the presence of the vector or correlate Ki-67 with sPLA2 expression. Future experiments will aim to correlate sPLA2 expression with Ki-67 staining, or proliferative potential in vivo.

CONCLUSIONS

sPLA2 IIa plays a significant role in modulating lung cancer cell growth. The relevance of sPLA2 IIa as a therapeutic target has expanding potential and studies investigating the expression of sPLA2 IIa in human tumor tissue are ongoing. Interestingly, group IIa sPLA2 inhibitors are available in both oral and intravenous formulations, having been tested in clinical trials for inflammatory disease with few adverse side effects noted in these study populations.24 The results of our study strongly support the rationale for investigating the efficacy of these agents in malignancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Courtney Pollard for providing technical advice, as well as Daniel T. Merrick, MD, and Francisco G. La Rosa, MD, University of Colorado, for their assistance in interpreting the histology.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- sPLA IIA

group IIa secretory phospholipase A2

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- shRNA

short-hairpin RNA

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

Biography

Dr Thomas Waddell (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2), as you mentioned, is part of a family that is involved in generating products of arachidonic acid downstream. And although a role in host defense, inflammatory injury, and atherosclerosis has been understood for many years, a specific role for cancer has been largely overlooked. So congratulations to you and your supervisor for a foray into this field.

You have convinced me that knockdown of sPLA2 results in inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B signaling and, as a result, proliferation in vitro and in vivo. I have some technical questions and 1 overview question. You show nicely that the S2 short-hairpin RNA was the best 1 of the 3 that you examined in terms of its effect on reducing phospholipase A2 (PLA2), but what about off-target effects? Is it the most specific molecule? Were there actually any effects on other members of the PLA2 family?

Dr Jessica Yu. We actually have looked at 1 other family member, group IV cystosolic PLA2, and the level does not change substantially with sPLA2 inhibition. I have not yet looked at cytosolic phospholipases A2 in the knockdown. There are 12 groups of PLA2 enzymes, so it would be difficult to investigate all of them.

Dr Waddell. On to the next question. I would like to come back to the data you presented about Ki67 being positive on the perimeter of the tumors growing in vivo. Do you have any speculation as to why that finding might have been seen?

Dr Yu. That is an interesting question with several possibilities. Cells in the dish are under constant selection with puromycin, and when we inject the tumor cells into mice, they are no longer in a selected environment. I did batch selection, not clonal selection, and was actually surprised to see a difference with that technique.

So maybe the perimeter is where we see proliferation of cells that are no longer being selected for. Another possibility is, of course, interactions with the microenvironment at the perimeter that stimulate proliferation. Microenvironment interaction would be another interesting study.

Dr Waddell. I think both are good. A third I would suggest thinking about is the hypoxic environment at the center of the tumor. In fact, a knockdown of PLA2 may make cells more sensitive to hypoxia.

Next I have a general overview question about the interaction between malignancy and inflammation. Given that this is a secreted molecule, what do you think about the possibility of transactivation of malignant cells by inflammatory leukocytes recruited to the tumor and secreting PLA2?

Dr Yu. Paracrine signaling has been documented by other groups—sPLA2 group IIa activation of lung macrophages, specifically. So that likely plays a role.

Dr Waddell. The specific experimental suggestion I have in this context is to do mixtures experiments with the tumors or even just of your transduced tumor cells. If you are looking for an autocrine inhibitory effect, you might see it if you have a small proportion of the S2 knockdown cells mixed in with wild-type cells.

Dr Yu. Yes, that is a good idea.

Dr Dao Nguyen (Miami, Fla). I noticed you used 2 cell lines. The A549 K-Ras mutant and the H358 is p53 mutant and K-Ras wild type. Is it K-Ras wild-type?

Dr Yu. They are both K-Ras.

Dr Nguyen. My second question is, regarding the reduction of growth in vivo, can it be because the cells just slow down; they don’t die at all? So what is your next plan? We want to eradicate tumors. We don’t want them to slow down.

Dr Yu. Our inhibition experiments have demonstrated an apoptotic response with high concentrations of inhibitor. At a lower concentration of the inhibitor we see a little bit more of the cell cycle arrest phenomenon. In terms of the mechanisms behind the 2 different responses, I am not exactly sure yet how to explain that.

Dr Nguyen. You saw a reduction in cell proliferation. Did you look into cell cycle analysis to see if they actually arrest or if they undergo apoptosis or senescence?

Dr Yu. Our inhibitor experiments looked at that and I have seen apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. With the knockdown specifically, I haven’t looked at cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. But like you said, sPLA2 knockdown did slow tumor growth.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

Read at the 92nd Annual Meeting of The American Association for Thoracic Surgery, San Francisco, California, April 28-May 2, 2012.

References

- 1.Dong Z, Liu Y, Scott KF, Levin L, Gaitonade K, Bracken RB, et al. Secretory phospholipase A2-IIa is involved in prostate cancer progression and may potentially serve as a biomarker for prostate cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1948–55. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mauchley D, Meng X, Johnson T, Fullerton DA, Weyant M. Modulation of growth in human esophageal adenocarcinoma cells by group IIa secretory phospholipase A2. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:591–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadaria MR, Meng X, Fullerton DA, Reece TB, Shah RR, Grover FL, et al. Secretory phospholipase a(2) inhibition attenuates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in human esophageal adenocarcinoma cells. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1539–45. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu JA, Sadaria MR, Meng X, Mitra A, Ao L, Fullerton DA, et al. Lung cancer cell invasion and expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) are attenuated by secretory phospholipase A2 inhibition. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:405–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Dubois RN. Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:181–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLemore TL, Hubbard WC, Litterst CL, Liu MC, Miller S, McMahon NA, et al. Profiles of prostaglandin biosynthesis in normal lung and tumor tissue from lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3140–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krysan K, Reckamp KL, Dalwadi H, Sharma S, Rozengurt E, Dohaldwala M, et al. Prostaglandin E2 activates mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK pathway signaling and cell proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer cells in an epidermal growth factor receptor-independent manner. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6275–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heasley LE, Thaler S, Nicks M, Price B, Skorecki K, Nemenoff RA. Induction of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by oncogenic Ras in human non-small cell lung cancer. J Biol Chem. 1997;279:14501–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer AM, Dwyer-Nield LD, Hurteau GJ, Ketih RL, O’Leary E, You M, et al. Decreased lung tumorigenesis in mice genetically deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1517–24. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindbom J, Ljungman AG, Lindahl M, Tagesson C. Increased gene expression of novel cytosolic and secretory phospholipase A2 types in human airway epithelial cells induced by tumor necrosis factor-α and IFN-γ. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:947–55. doi: 10.1089/10799900260286650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernández M, Martín R, García-Cubillas MD, Maeso-Hernández P, Nieto ML. Secreted PLA2 induces proliferation in astrocytoma through the EGF receptor: another inflammation-cancer link. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:1014–23. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaulmes A, Janvier B, Andreani M, Raymondjean M. Autocrine and paracrine transcriptional regulation of type IIA secretory phospholipase A2 gene in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1161–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000164310.67356.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granata F, Frattini A, Loffredo S, Staiano RI, Petraroli A, Ribatti D, et al. Production of vascular endothelial growth factors from human lung macrophages induced by group IIA and group X secreted phospholipases A2. J Immunol. 2010;184:5232–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR, Li ZW. NF-κB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:301–10. doi: 10.1038/nrc780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanabe T, Tohnai N. Cyclooxygenase isozymes and their gene structures and expression. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68:95–114. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung YJ, Isaacs JS, Lee S, Trepel J, Neckers L. IL-1β mediated up-regulation of HIF-1α via an NFkB/COX-2 pathway identifies HIF-1 as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis. FASEB J. 2003;17:2115–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0329fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu JA, Kalatardi S, Dohse J, Sadaria MR, Meng X, Fullerton DA, et al. Group IIa sPLA2 inhibition attenuates NF-κB activity and promotes apoptosis in lung cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:3601–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dharmapuri S, Peruzzi D, Marra E, Palombo F, Bett AJ, Bartz SR, et al. Intratumor RNA interference of cell cycle genes slows down tumor progression. Gene Ther. 2011;18:727–33. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Seligson D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, et al. Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNAvia targeted nanoparticles. Nature. 2010;7291:1067–70. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marek L, Ware KE, Fritzsche A, Hercule P, Helton WR, Smith JE, et al. Fibroblast growth fact (FGF) and FGF receptor-mediated autocrine signaling in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:196–207. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khromova N, Kopnin P, Rybko V, Kopnin BP. Downregulation of VEGF-C expression in lung and colon cancer cells decelerates tumor growth and inhibits metastasis via multiple mechanisms. Oncogene. 2012;31:1389–97. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vignaud JM, Marie B, Klein N, Plenat F, Pech M, Borrelly J, et al. The role of platelet-derived growth factor production by tumor-associated macrophages in tumor stroma formation in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5455–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley JD, Dmitrienko AA, Kivitz AJ, Gluck OS, Weaver AL, Wisenhutter C, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial of LY333013, a selective inhibitor of group II secretory phospholipase A2, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:417–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]