Abstract

We identified two novel GATA2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). One mutation (p.R308P-GATA2) was a R308P substitution within the zinc finger (ZF)-1 domain, and the other (p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2) was an eight-amino-acid insertion between A350 and N351 residues within the ZF-2 domain. p.R308P-GATA2 did not affect DNA-binding and transcriptional activities, while p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 reduced them, and impaired G-CSF-induced granulocytic differentiation of 32D cells. Although p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 did not show a dominant-negative effect over wild-type (Wt)–GATA2 by the reporter assay, it might be involved in the pathophysiology of AML by impairing myeloid differentiation because of little Wt-GATA2 expression in primary AML cells harboring the p.A350_N351ins8 mutation.

Keywords: GATA2, AML, Mutation, Differentiation

1. Introduction

GATA transcription factors contribute to the regulation of cell lineage commitment and differentiation.1 Although hematopoiesis is controlled by numerous transcription and signaling factors with tightly integrated functions, GATA1, GATA2 and GATA3 in the GATA family are involved in the developmental regulation of hematopoiesis. In addition to the essential role in normal hematopoiesis, recent studies demonstrated that mutation of GATA genes is involved in the development and progression of leukemia. p.L359V mutation of GATA2 gene was identified in about 10% of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cases at accelerated phase and myeloid blast crisis.2 Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that GATA2 gene mutations were identified in AML patients and in three different familial syndromes characterized by predisposition to myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and AML.3–5 These results collectively indicate that dysregulation of GATA2 might be involved in the development and/or progression of AML.

In this study, we analyzed the biological effects of two novel GATA2 mutations, which were identified in adult de novo AML patients.

2. Materials and methods

The diagnosis of AML was based on the morphology, histopathology, the expression of leukocyte differentiation antigens and/or the French–American–British (FAB) classification. GATA2 mutation was screened in 96 newly diagnosed de novo AML adult patients. Informed consent was obtained from all patients to use their samples for banking and molecular analysis, and approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Nagoya University School of Medicine.

The full-length human wild-type (Wt)- and mutated (Mt)-GATA2 cDNAs were amplified from Wt- or Mt-GATA2-expressing leukemia cells, respectively. C-terminally Myc-tagged GATA2 cDNAs were cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector, and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and luciferase assay were performed as previously reported.6

C-terminally Myc-tagged Wt- and mutant-GATA2 cDNAs cloned in the pMX-IP vector were transduced into murine IL3-dependent myeloid progenitor cell line 32D cells as previously described.7 Stable Wt- and mutant-GATA2-expressing 32D cells were subjected to immunofluorescence, proliferation and differentiation analyses.

Wt- and mutant-GATA2-expressed 32D cells were suspended in RPMI1640 medium containing 10% FCS with an increasing concentration of murine IL3 (R&D Systems), and 2×104 cells per well were seeded in 96-well culture plates. Cell viability was measured using the CellTiter96 Proliferation Assay (Promega). For the induction of myeloid differentiation, Wt- and mutant-GATA2-expressed 32D cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium containing 10% FCS and 30 ng/ml recombinant G-CSF (Kyowa-Kirin, Tokyo, Japan) without IL3.

Luciferase assay and cell proliferation and differentiation analyses were performed three times independently. Differences in continuous variables were analyzed with unpaired t test for the distribution between two groups using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). For all analyses, the P values were two-tailed, and a P value<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

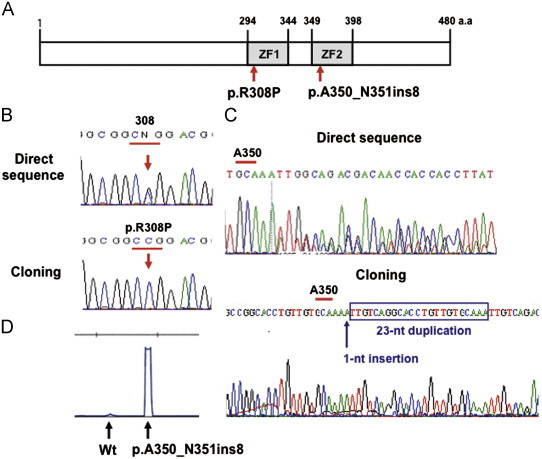

We identified two GATA2 gene mutations. One mutation (p.R308P-GATA2) was a p.Arg308Pro substitution within the N-terminal zinc finger (ZF)-1 domain in a FAB M6 patient (Fig. 1A and B). The other mutation (p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2) was a 24-nucleotide insertion resulting in an eight-amino-acid insertion between A350 and N351 residues within the C-terminal ZF-2 domain in a FAB M1 patient. This insertion mutation consisted of a one nucleotide insertion and a 23-nucleotide corresponding to N337-R344 residues duplication (Fig. 1A and C). In both patients, each GATA2 mutation was heterozygous. Unfortunately, we could not analyze germ-line sequence of both patients because of the lack of appropriate material. Therefore, we could not completely determine whether identified mutations were somatic or germ-line mutations.

Fig. 1.

GATA2 mutations identified in AML. (A) Two novel GATA2 mutations that were identified are shown in the domain structure of GATA2. Two zinc finger domains are indicated by ZF-1 and ZF-2. (B) The sequence diagram of p.R308P mutation. The upper and lower panels show the direct-sequence result and the sequence result after cloning procedure, respectively. (C) The sequence diagram of p.A350_N351ins8 mutation. The upper and lower panels show the direct-sequence result and the sequence result after cloning procedure, respectively. (D) Expression ratio of Wt- and p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 transcripts of primary AML cells. Little expression of Wt-GATA transcript was observed in the primary AML cells.

Both patients revealed normal karyotype and no mutation in FLT3, KIT, NRAS, TP53, NPM1, CEBPA, RUNX1, MLL-PTD and IDH1/2 genes.

The expression ratios of Wt- and Mt-GATA2 transcripts of AML cells harboring the p.A350_N351ins8 mutation were semi-quantitatively examined using a gene scanning system with fluorescent-labeled PCR product. Although the p.A350_N351ins8 mutation was heterozygous, little expression of Wt-GATA transcript was observed in the primary AML cells (Fig. 1D).

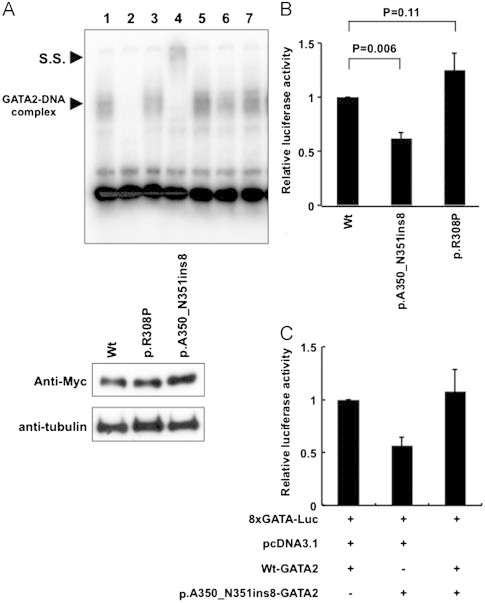

We transiently expressed Wt- and mutant-GATA2 in 293T cells, and nuclear lysates were extracted 48 h later. In EMSA using an oligonucleotide containing GATA recognition sites, DNA-binding activity of p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 was reduced to about 40% of that of Wt-GATA2, although that of p.R308P-GATA2 was almost the same as that of Wt-GATA2 (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the DNA-binding activity, the transcriptional activity of p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 was significantly lower than that of Wt-GATA2 (P=0.006), while that of p.R308P-GATA2 was not affected (P=0.11) (Fig. 2B). Upon co-expression of Wt-GATA2 with p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 at a 1:1 ratio, the transcriptional activity of Wt-GATA2 was not affected by p.A350_N351ins8-GATA, indicating that p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 did not have a dominant-negative effect over Wt-GATA2 (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of mutant GATA2. (A) The DNA-binding activities of Wt- and Mt-GATA2 were evaluated by EMSA using an oligonucleotide containing GATA recognition sites. Wt-GATA2 showed the GATA2-DNA complex band (lanes 1 and 5). This band was competed by a 200-fold excess of the unlabeled oligonucleotide (lane 2), and was super-shifted by the addition of anti-GATA2 antibody (lane 4), but not control IgG (lane 3). DNA-binding activity of p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 was reduced to about 40% of that of Wt-GATA2 (lane 6). In contrast, p.R308P-GATA2 showed almost the same DNA-binding activity as Wt-GATA2 (lane 7). Lower panel shows expression levels of Wt- and Mt-GATA2 proteins in 293 T cells. (B) Transcription activities of Wt- and Mt-GATA2 were evaluated by luciferase reporter assay. 293 T cells were transfected with Wt- or Mt-GATA2 cloned pcDNA3.1 vectors together with a luciferase reporter plasmid containing eight GATA consensus motifs. The transcription activity of p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 was significantly lower than that of Wt-GATA2 (P=0.006), while that of p.R308P-GATA2 was not affected. Mean ±SEM of three independent analyses are shown. (C) Upon co-expression of Wt-GATA2 with p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 at a 1:1 ratio, the transcriptional activity of Wt-GATA2 was not affected by p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2, indicating that p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 did not have a dominant-negative effect over Wt-GATA2. Mean±SEM of three independent analyses are shown.

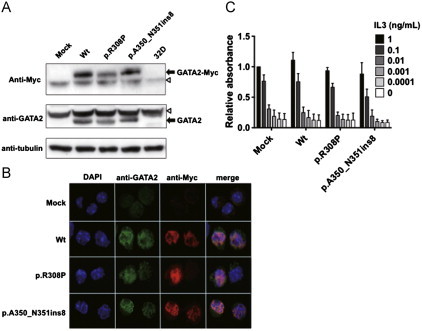

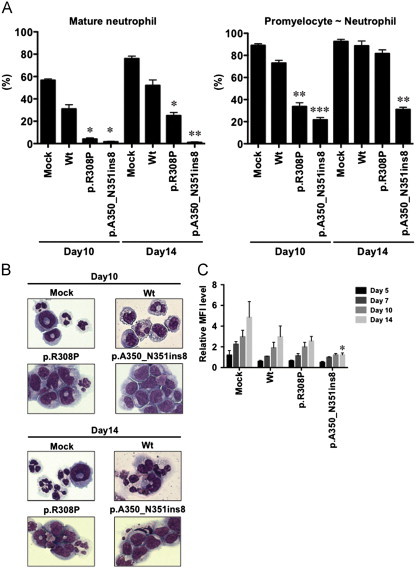

We established Wt- and two Mt- (p.R308P and p.A350_N351ins8)-GATA2-expressing 32D cells to analyze the cellular effects of Mt-GATA2 (Fig. 3A). Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that Mt-GATA2 showed similar localization in the nucleus as Wt-GATA2 (Fig. 3B). Both Wt- and mutant-GATA2-expressing 32D cells did not show autonomous proliferation without the presence of IL3. Furthermore, there was no difference of proliferation abilities at lower concentrations of IL3 between them, indicating that mutant GATA2 did not provide a growth advantage (Fig. 3C). Since mutant GATA2 did not affect the proliferation ability, we examined the G-CSF-mediated granulocytic differentiation in Wt- and Mt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells. Mock- and Wt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells were differentiated to mature neutrophils in the culture with G-CSF for 10 days, while Wt-GATA2 overexpression moderately impaired the granulocytic differentiation. In p.R308P-GATA2-expressing 32D cells, mature neutrophil counts and promyelocyte to neutrophil counts were significantly lower than those of Wt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells after the 10-day culture (P=0.020 and P=0.003, respectively), while promyelocyte to neutrophil counts were the same after the 14-day culture. However, in p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2-expressing 32D cells, mature neutrophil counts and promyelocyte to neutrophil counts were significantly lower than those of Wt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells both after the 10-day and the 14-day cultures (P=0.016 and P=0.0005 after 10 days, and P=0.009 and P=0.007 after 14 days, respectively), indicating that p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 impaired the G-CSF-mediated granulocytic differentiation (Fig. 4A and B). These morphological results were confirmed by the surface expression of CD11b after G-CSF stimulation (Fig. 4C). CD11b expression levels of p.R308P-GATA2-expressing 32D cells were the same as Wt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells, while that of p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2-expressing 32D cells was significantly lower than those of Wt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells on day 14 (P=0.04).

Fig. 3.

Establishment of Wt- and Mt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells. (A) Stable expression of GATA2 protein in each cell line was confirmed by Western blotting using anti-Myc (upper panel) and anti-GATA2 (lower panel) antibodies. Of note is that no expression of endogenous GATA2 was observed in 32D cells. White arrowhead indicates non-specific band. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis showed the same localization of Wt- and Mt-GATA2. C. Ratio of cell viability of each GATA2-expressing 32D cell to mock-32D cells after 72-h culture at variable concentrations of IL3 is presented. Cell viability was measured using the CellTiter96 Proliferation Assay (Promega). Mean±SEM of three independent analyses are shown. There was no significant difference of proliferation abilities between Wt- and Mt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells.

Fig. 4.

G-CSF-induced granulocytic differentiation. (A) Granulocytic differentiation of G-CSF-treated 32D cells was morphologically determined. One hundred cells were counted in each experiment. Mean±SEM of three independent analyses are shown. Mature neutrophil counts (left panel) and promyelocyte to neutrophil counts (right panel) on Day 10 and Day 14 were compared with Wt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells. (B) Morphological features of Wt- and Mt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells are shown. (C) The relative MFI level of CD11b to isotype after the G-CSF treatment in Mt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells were compared with Wt-GATA2-expressing 32D cells. Mean±SEM of three independent analyses are shown. ⁎P<0.05, ⁎⁎P<0.01, ⁎⁎⁎P<0.001.

4. Discussion

In this study, we identified two novel GATA2 gene mutations (p.R308P in the ZF-1 domain and p.A350_N351ins8 in the ZF-2 domain) in adult de novo AML patients. Most mutations in the ZF-2 domain of the GATA2 gene are reportedly missense mutations.8 Although three types of in-frame deletion mutations were reported, p.A350_N351ins8 mutation was firstly identified as an in-frame insertion mutation in the ZF-2 domain. L359V mutation, which was recurrently identified in CML-BC, increased transactivation activity and inhibited myelomonocytic differentiation and proliferation.2 In contrast, T354M and T355del mutations, which were identified in families with hereditary MDS/AML, dominant-negatively reduced transactivation activity over Wt-GATA2.3 However, it is notable that T354M-GATA2 inhibited the all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA)-induced granulocytic differentiation of HL-60 cells, but T355del-GATA2 did not. Consistent with the T354M mutation, p.A350_N351ins8 mutation reduced DNA-binding and transcriptional activities and impaired G-CSF-induced granulocytic differentiation of 32D cells. However, in contrast to T354M-GATA2, p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 did not show a dominant-negative effect over Wt-GATA2 by transcriptional assay. Since p.A350_N351ins8 mutation was heterozygous in the clinical sample, this result raised the question of how this mutation is involved in leukemogenesis, particularly in the impairment of granulocytic differentiation. In 32D cells, endogenous GATA2 expression was very faint by western blot and immunohistochemical analyses. Furthermore, Wt-GATA2 transcript was expressed little in the primary AML cells harboring p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 mutation. These results suggested that p.A350_N351ins8-GATA2 might act as a loss of function of GATA2 in the absence of Wt-GATA2, resulting in the impairment of granulocytic differentiation.

Recently, several kinds of missense mutations within the ZF-1 domain were reported in AML.5 Although transcriptional activities of GATA2 ZF-1 mutants were different among the mutation types, all of them reduced the capacity to enhance CEBPA-dependent activation of transcription.5 p.R308P-GATA2 did not show significant reduction of DNA-binding and transcriptional activities, while p.R308P-GATA2-expressing 32D cells revealed the delay of G-CSF-induced granulocytic differentiation, suggesting a possible effect on maturation machinery through the reduction of CEBPA-dependent transcriptional activity.

In addition, further study is required to evaluate whether identified mutations influence post-translational modifications because they are important mechanism of transcription factors for regulating normal and leukemic hematopoiesis.6,9–11

Authors' contributions

K. N., Y. I., F. H., S. K. and R. K. performed experiments. K. N., H. K. and A. T. interpreted the data. H. K. and T. N. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Manami Kira, Mirei Okamoto and Satomi Yamaji for secretarial and technical assistance. This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare for Cancer Research (Clinical Cancer Research H23-004) and the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (23-A-23), the Scientific Research Program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and the Global COE Program “Integrated Functional Molecular Medicine for Neuronal and Neoplastic Disorders” Japan.

References

- 1.Orkin S.H. Diversification of haematopoietic stem cells to specific lineages. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2000;1:57–64. doi: 10.1038/35049577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang S.J., Ma L.Y., Huang Q.H., Li G., Gu B.W., Gao X.D. Gain-of-function mutation of GATA-2 in acute myeloid transformation of chronic myeloid leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:2076–2081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711824105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn C.N., Chong C.E., Carmichael C.L., Wilkins E.J., Brautigan P.J., Li X.C. Heritable GATA2 mutations associated with familial myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:1012–1017. doi: 10.1038/ng.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostergaard P., Simpson M.A., Connell F.C., Steward C.G., Brice G., Woollard W.J. Mutations in GATA2 cause primary lymphedema associated with a predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia (Emberger syndrome) Nature Genetics. 2011;43:929–931. doi: 10.1038/ng.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greif P.A., Dufour A., Konstandin N.P., Ksienzyk B., Zellmeier E., Tizazu B. GATA2 zinc finger 1 mutations associated with biallelic CEBPA mutations define a unique genetic entity of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:395–403. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-403220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozawa Y., Towatari M., Tsuzuki S., Hayakawa F., Maeda T., Miyata Y. Histone deacetylase 3 associates with and represses the transcription factor GATA-2. Blood. 2001;98:2116–2123. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiotsu Y., Kiyoi H., Ishikawa Y., Tanizaki R., Shimizu M., Umehara H. KW-2449, a novel multikinase inhibitor, suppresses the growth of leukemia cells with FLT3 mutations or T315I-mutated BCR/ABL translocation. Blood. 2009;114:1607–1617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyde R.K., Liu P.P. GATA2 mutations lead to MDS and AML. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:926–927. doi: 10.1038/ng.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Felice L., Tatarelli C., Mascolo M.G., Gregorj C., Agostini F., Fiorini R. Histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid enhances the cytokine-induced expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Cancer Research. 2005;65:1505–1513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez S., Wang L., Mumaw C., Srour E.F., Lo Celso C., Nakayama K. The SKP2 E3 ligase regulates basal homeostasis and stress-induced regeneration of HSCs. Blood. 2011;117:6509–6519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu J., Zhou J., Peres L., Riaucoux F., Honore N., Kogan S. A sumoylation site in PML/RARA is essential for leukemic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]