Abstract

Background

The stress of a breast cancer diagnosis and its treatment can produce a variety of psychosocial sequelae including impaired immune responses. Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) is a structured complementary program that incorporates meditation, yoga and mind-body exercises. Despite promising empirical evidence for the efficacy of MBSR, there is a need for randomized controlled trials (RCT). There is also a need for RCTs investigating the efficacy of psychosocial interventions on mood disorder and immune response in women with breast cancer. Therefore, the overall aim is to determine the efficacy of a Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) intervention on well-being and immune response in women with breast cancer.

Methods and design

In this RCT, patients diagnosed with breast cancer, will consecutively be recruited to participate. Participants will be randomized into one of three groups: MBSR Intervention I (weekly group sessions + self-instructing program), MBSR Intervention II (self-instructing program), and Controls (non-MBSR). Data will be collected before start of intervention, and 3, 6, and 12 months and thereafter yearly up to 5 years. This study may contribute to evidence-based knowledge concerning the efficacy of MBSR to support patient empowerment to regain health in breast cancer disease.

Discussion

The present study may contribute to evidence-based knowledge concerning the efficacy of mindfulness training to support patient empowerment to regain health in a breast cancer disease. If MBSR is effective for symptom relief and quality of life, the method will have significant clinical relevance that may generate standard of care for patients with breast cancer.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01591915

Keywords: Breast cancer, Mindfulness based stress reduction, Randomized controlled trials, Well-being

Background

Breast cancer is one of the most feared diseases among women, and for many women a breast cancer diagnosis and its subsequent treatment are accompanied by dealing with a spectrum of physical and psychological challenges [1,2]. Women with breast cancer are at risk of psychological morbidity [3], and up to 30% of women diagnosed with breast cancer develop mood disorder, either anxiety or depressive symptoms, within one year of diagnosis [4,5]. While breast cancer is a major stressor for any woman, there is great variability in women’s emotional responses and their ability to mobilize the resources to cope with distress. However, although levels of distress tend to decrease over time, a subset of women with breast cancer remain highly distressed [6,7]. A growing area of interest is the personal growth and transformation of individuals as they adjust to a life-altering event and an increasing body of literature illustrates that many people experience significant personal growth despite severe trauma or disease [8,9]. Notwithstanding recurrent breast cancer, women who view their disease as a challenge and an opportunity for personal change are able to create wellness by being in the present moment [10].

The stress of a breast cancer diagnosis and its treatment can produce a variety of psychosocial sequelae including impaired immune responses [11]. An increasing body of research indicates that stress-related psychosocial factors are associated with higher cancer incidence and higher mortality [12]. Data suggest that psychological stress has a significant negative effect on cellular immune responses, such as lowered natural killer cells (NK cells) and T lymphocytes (T cells) [13]. Previous research indicates that NK and T cells are sensitive to different aspects of the stress response in women with breast cancer [14]. In addition, T cells have been linked to recurrence [15] and survival [16]. Other important parameters are cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-8 (IL-8), which independently show correlations with breast cancer disease stage and progression [17-20].

The recognition of psychosocial needs in cancer patients has led to the development of psychosocial interventions, indicating a variety of positive effects on coping, quality of life, emotional and functional adjustment [21,22]. The literature on psychosocial interventions for cancer fails to meet criteria for establishing treatment efficacy and does not address issues of cost-effectiveness [23]. Although evidence suggests beneficial effects of psychosocial interventions [21,22], the physiological benefits for breast cancer patients remain unclear [24]. Furthermore, there are no existing large-scale studies prospectively investigating the efficacy of psychosocial intervention on coping and immune response in women with breast cancer [24].

Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) is a standardized program incorporating mindfulness meditation, yoga practices and other techniques designed to reduce suffering and improve health and well-being in patients with a wide range of chronic pain and stress disorders [25-27]. MBSR has also been shown to improve mood and reduce symptoms of stress in mixed groups of cancer patients [28]. The primary goal of MBSR is to develop the capacity to be aware in each moment, by “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally” [25]. MBSR is a structured group-formatted 8-week course, attended once a week by patients for an average of 2 hours, together with daily practice of homework assignments. While noting the efficacy of MBSR on different patient populations, several reviews have pointed out the inherent methodological problems in the published studies [29,30]. Two systematic reviews of MBSR interventions for the treatment of anxiety and depression emphasize the methodological shortcomings which create uncertainties about the efficacy of treatment. The reviewed studies that reported a statistically significant reduction in anxiety and depression did not include control groups or follow-up data, and future studies with improved methodologies are needed to test the efficacy of the mindfulness component of the intervention [31,32].

The MBSR program was shown to have beneficial effects on immune function, reduced cortisol levels, improved Quality of Life (QoL), and increased coping effectiveness in a non-randomized group of women with breast cancer as compared with women who received the usual care [33]. A recent randomized study [34] showed that cancer patients who received a mindfulness intervention reported less perceived stress and posttraumatic avoidance symptoms and increased positive states of mind. This study indicates that the improvements in psychological well-being resulting from the MBSR intervention could have been explained in terms of increased levels of mindfulness. Other study results indicate a positive adjustment of cortisol levels as a result on MBSR program [35]. Evidence from uncontrolled studies of breast and prostate cancer patients also suggests that MBSR improved QoL and decreased stress symptoms [36], and altered cortisol and immune patterns [37]. Study results suggest that MBSR may influence the functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis [35,38]. These pilot data from studies investigating the relationships between MBSR and hormone levels highlight the need for better-controlled studies in this area [38]. These results raise important questions as to whether mindfulness based interventions actually enhance mindfulness and whether such changes in mindfulness are related to positive outcome in the experience of health, strengthened immune system or disease-free survival.

Despite promising empirical evidence that the efficacy of MBSR improves mood and reduces symptoms of stress, there is a need for randomized, controlled studies including homogenous patient populations and using reproducible and stringent methodological procedures. In addition to self-reported psychosocial and functional measures of health and illness, assessment of biological markers are also needed in future mindfulness based interventions [30].

Aim and outcome measurements

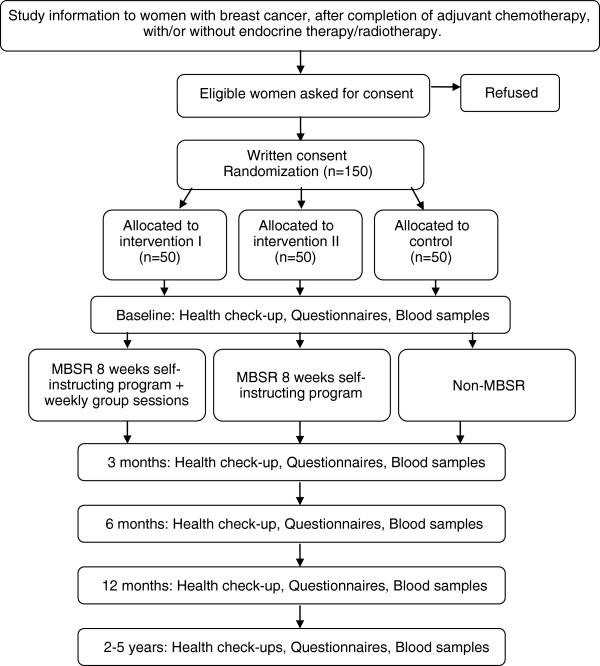

The overall aim is to determine the efficacy of a Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) intervention on well-being and immune response in women with breast cancer. This paper presents in-depth information on the design of the study (Figure 1). The study design follows the Consort recommendations [39-41].

Figure 1.

Study design including enrollment, allocation and follow-up. MBSR = Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction.

Primary outcome

The efficacy of MBSR on mood disorders, evaluated in terms of anxiety and depression.

Secondary outcomes

The efficacy of MBSR on:

● coping capacity,

● symptom experience,

● quality of life,

● health status,

● personal growth,

● level of mindfulness,

● physiological response, disease progression, survival,

● analyses of utility and health economics, and

● analyses of the usability of MBSR in clinical care.

Methods

Design

Patients diagnosed with early stage breast cancer will be consecutively recruited from two surgical centers, to participate in this three-armed randomized controlled complementary intervention study. The study design is presented in Figure 1.

Written consent will be obtained before enrolment. Confidentiality will be assured, and participants will be advised that they are free to withdraw from the study at any time, and respect will be given to the participant’s condition. The study is registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01591915.

Participants

In this randomized, controlled intervention study, patients diagnosed with breast cancer will be consecutively recruited to participate after completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, with/or without endocrine therapy.

Research nurses will contact eligible patients at the first follow-up appointment for patients receiving hormonal therapy or at the last treatment for patients undergoing chemotherapy. After oral and written information, interested patients will provide written consent to participate in the study. Participants who agree to participate will be invited to a first baseline health check-up appointment, including collection of blood samples, completion of questionnaires, a health check-up, and finally random assignment to one of three groups. Randomization will be conducted in blocks of 9, 12 and 15 blocks varied randomly. The assignment codes will be kept in sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, prepared by the research team. At the time of allocation, the research nurse will pick the sequential envelope, write the participant’s name and personal registration number on the envelope, and then open it.

Inclusion criteria

Patients diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer:

receiving hormonal therapy, or:

after completion of adjuvant chemotherapy,

with or without radiotherapy

Exclusion criteria

Patients with other advanced illness at diagnosis, and/or:

ongoing major depression

ongoing Herceptin therapy

previously use of MBSR

Training of instructors

Trained by a senior MBSR instructor, four registered nurses, skilled in patient learning, have been trained as certified MBSR instructors. Briefly, the instructor training consists of: 1 day of introduction to MBSR; 8 weeks of instructors’ own MBSR practice including 20 minutes sessions, 6 days/week; 2 days focused on practical training in group sessions; 8 week course in leading a group of patients who attend once a week for an average of 2 hours; 2 days focused on instructors’ experience of leading patient groups; and 1 day examination and certification.

Intervention

It is well known that attention, expectations and good caring treatment contribute to the placebo effect. In order to minimize the impact of a situation with “a self-selected treatment and caring response to an enthusiastic therapist may be part of the active components of the alternative medical field” [42], two intervention groups and one control group will be included. All women receive standard care (SC) according to the national and local guidelines recommendations [43].

Participants will be randomized into one of three groups:

– SC and MBSR Intervention group I (8 weeks self-instructing program + instructor and weekly group sessions)

– SC and MBSR Intervention group II (8 weeks self-instructing program)

– SC and Non-MBSR (Controls)

Participants in MBSR Intervention group I and MBSR Intervention group II will participate in an 8-week tutorial of MBSR practice with homework assignments consisting of 20 minutes sessions, 6 days/week. Participants will be provided with information material including a 20-page introduction to mindfulness training, CD, diary and training program. Only participants in MBSR Intervention group I will take part in a structured group-formatted 8-week course that patients attend once a week for an average of 2 hours. Led by a certified MBSR instructor, these weekly group sessions will be focused on the participant’s experience of mindfulness, and include gentle yoga and meditation training. Owing to the differences between the two interventions groups, blinding will not be possible.

Data collection

Socio-demographic data will be collected through chart review and interviews. Data characteristics are age, marital status, living situation, employment status, children, occupation and educational level. Clinical characteristics investigated are type of treatment, tumor characteristics, and co-morbidity. Patient self-reported response (questionnaires) and immune response (blood samples) will be collected, and health checks conducted, at baseline (before start of intervention), after the intervention for MBSR Intervention groups I and II, follow-up will be conducted one months after the intervention, and at similar time points of 3 months (non-MBSR), 6 months, 12 months, and thereafter yearly up to 5 years. Health checks including current health status and treatment, and blood samples will be performed by research nurses. Patient outcome will be collected by following the questionnaires, health check-ups and bio-markers.

Measuring outcomes

Primary outcome

Mood disorder

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) is one of most widely used instruments to screen for anxiety and depression or psychosocial distress in cancer patients [44-46]. HAD is a 14-item questionnaire consisting of two sub-scales, anxiety and depression. Each response is rated on a four-point scale. Subscale scores range from 0 to 21. Scores of 0–7 indicate “normal”, 8–10 “borderline” and scores of >11 or more on either sub-scale are considered to represent risk of psychological morbidity [44-47]. The internal consistency of reliability for HAD Depression and HAD Anxiety are satisfactory, with Cronbach’s alpha 0.72 - 0.89, respectively 0.78 - 0.93 [46].

Secondary outcomes

Coping capacity

Personal coping resources are evaluated using the Sense of Coherence scale (SOC) [48,49]. The SOC short version scale consists of 13 items on a 7-point Likert scale. The SOC scale evaluates perceived comprehensibility (5 items), manageability (4 items) and meaningfulness (4 items). A higher score represents a stronger sense of coherence [50]. The reliability and validity of the SOC scale has been proven in many studies and different languages with a Cronbach’s α range of 0.74 to 0.93 [51-53].

Symptom experience

Symptoms (frequency, severity and distress) are measured using the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS), a multidimensional questionnaire consisting of 32 symptoms [54]. The MSAS generates the Total Symptom Burden Scale (TMSAS) and the Global Symptom Distress Index (GDI). The MSAS has been proven to be a reliable and valid multidimensional measure of symptom experience in cancer populations [54,55].

Health-related quality of life

Breast cancer specific HRQoL is evaluated using the 10 item visual analogue scale of the International Breast Cancer Study Group Quality of Life Core Questionnaire (IBCSG QoL). The questionnaire includes global indicators for physical well-being, mood, coping, social support and subjective health estimation, and indicators of symptoms covering possible specific disease and treatment-related effects. Higher scores indicate a higher level of symptoms/problems. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire has been established in several studies [56,57].

Health status

The SF-36 measures eight domains of health including physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health [58]. The SF-36 yields a score for each of these eight domains, a total score for physical and mental health, and a global health utility index. Maximum score is 100 points. Higher scores indicate better health status. The reliability measurements of the SF-36 are consistently good [58-61].

Personal growth

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) is a measure of positive life changes after traumatic or life-altering events [62]. The PTGI consist of 21 items, rated on a 6-point Likert scale, divided into five dimensions: Relating to others (7 items), New possibilities (5 items), Personal strength (4 items), Spiritual change (2 items), and Appreciation of life (3 items). The PTGI yields a score for each of these subscales, and a total score. The PTGI has shown good reliability in previous research of breast cancer survivors, with Cronbach’s alpha for the PGI total score was 0.96 [63].

Mindfulness

Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ short form). FFMQ developed by Baer and colleagues [64]. The FFMQ short form consists of 29 items, and yield five factors that appear to represent elements of mindfulness as it is currently conceptualized: Observing, Describing, Acting with awareness, Non-judging of inner experience and Non-reactivity to inner experience.

Blood sampling

NK cell function will be measured using a newly developed assay called flow cytometric assay of natural killer cell immune response in activated whole blood (FANKIA; 1). Briefly the cell line K562 is mixed with whole blood and the mix is centrifuged and incubated in 37°C for 2 hours. After staining with an antibody that recognizes K562, the number of remaining K562 cells is determined using flow cytometry and the lytic activity of the NK cells is calculated. Flow cytometry will be performed using a standard multicolour procedure to detect the main lymphocyte populations in human blood. Staining for regulatory T cells will also be performed. Cytokine analyses of IL-6 and IL-8 in serum will be performed using the automatic enzyme immunoassay system Immulite 1000 according to the standard procedure from the manufacturer.

Health check-ups

Research nurses will conduct health check-ups including blood pressure and heart rate, at baseline and follow-ups. A protocol for baseline socio- demographics and medical characteristics, and follow-up protocols for current medical conditions, including disease progression, will be used to report health status.

Analyses of utility and health economics and usability of MBSR

The utility of MBSR in clinical settings, and health economic impact and costs will be described in relation to sick leave, health care patterns, drug costs and mortality.

Sample size calculation

To detect significant differences between three groups (MBSR Intervention I and II, and non-MBSR): 50 participants per group (150 participants in total) are needed in order to achieve a statistical power of 80%. The power calculation was based on alpha of 0.05 and expected mean effect size difference between the groups (difference in change between baseline and 3 months follow-up) being at least 1 unit at HAD-scale.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics will be used to summarize socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. Pearson’s correlation coefficient will be calculated to determine the strength of relationships between selected variables. Univariate and multivariate analyses of variance for repeated measures (ANOVA/MANOVA) will be used to compare between groups. For comparison of skewed variables, a non-parametric test will be used. Regression analyses will be used to identify predictors. In multivariable stepwise procedures only variables that provide statistically significant contributions will be included in the analyses (p < 0.05).

Interviews

With the purpose of exploring how participants experience the effects of MBSR on mood and HRQoL, interviews will be conducted. A further purpose, from a patient perspective, is to examine whether MBSR is clinically relevant as a complementary method in breast cancer. With the purpose of describing the process over time, repeated interviews will be conducted during and after the intervention. Grounded theory is a qualitative method tailored to exploring processes, actions and meaning. It is a systematic method of comparative analysis and a strategic method of generating theory grounded in data [65,66].

Quality aspects

The following competences are represented in the research group: Research manager Elisabeth Kenne Sarenmalm, RN, PhD, Adjunct Lecturer, Research and Development Center, Skaraborg Hospital, Skövde, Institute of Health and Caring Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy at University of Gothenburg, experienced in research in breast cancer patients, expert in psycho-oncology, and a certified MBSR instructor. Lena B Mårtensson, RNM, PhD, Associate Professor, Schools of Life Sciences, University of Skövde, and expert in randomized controlled trials in complementary methods. Stig B Holmberg, specialist in tumor surgery, MD, Associate Professor, Breast Department, SU/Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, medical advisor, expert in international, randomized, controlled breast cancer trials, and patient recruitment. Bengt A Andersson, specialist in clinical immunology, MD, Associate Professor, Immunological Laboratory, SU/Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, clinical immunological advisor and expert in stress and immune response. Anders Odén, Professor in Biostatistics, at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, statistical advisor and expert in statistical methods, biostatistics, statistical aspects of epidemiology. Ingrid Bergh, RN, PhD, Professor, Schools of Life Sciences, University of Skövde, and expert in patient-reported outcomes assessment.

The senior MBSR instructor will continue as a supervisor during the intervention in order to support MBSR instructors and establish internal validity. A research controller, responsible for logistics and protocol monitoring, and coordinating follow-ups, provide guarantee for sustainability. Four research nurses, responsible for inclusion, randomization and health check-ups, is a guarantee for continuity during follow-up. Finally, continuous monitoring will ensure that the intervention is implemented according to protocol, and with inclusion and exclusion of participants follow-up to avoid selection bias. Exclusion of patients, including reason for exclusion, will be reported in a reject log. Process evaluations will be conducted using intermittent checks in order to assure that the intervention procedures are performed correctly and follow the study protocol.

Ethical considerations

In studies including patients diagnosed with a serious illness such as breast cancer, ethical problems may arise. Fundamental ethical principles including respect for individuals, and not causing harm will be observed. The risk of privacy intrusion is minimized by requiring informed consent. Participation in the study is voluntary and can always be discontinued if the patient so desires. Responsiveness and flexibility about the patient’s condition and motivation for participating in the study will considered. Ethical approval has been granted by the Etichal Research Committee, University of Göteborg D:nr 499–9; 12/11/2009. Approval has also been granted by the medical directors of the participating hospitals.

All patient data from the study are confidential and no unauthorized person will have access to this information. In data processing, name and personal identity number will be replaced by a code so that no individual can be identified. Only the principal investigator of the study will have access to the code key. In published study reports, individuals will not be identified. Handling personal data in Sweden is governed by the Personal Data Act [67]. All data will be computer processed and stored for at least 10 years.

The blood samples will be stored encrypted, and will not be directly traceable back to individuals. The samples, as well as a corresponding identification list (code key), will be stored safely and separately. Samples may be used only in ways to which the participants consented. They can only be made available to a new research project after participants submit a new agreement and/or approval is granted by the Ethical Research Committee. The participant has the right to request, without explanation, that samples be destroyed or made anonymous according to the Swedish act “Biobanks in Medical Care Act” [68].

Discussion

Women with breast cancer have unique rehabilitation needs. As the most common invasive cancer disease among women worldwide, a high frequency of both physical and psychological problems follows breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. The major goal of rehabilitation is to help each patient to achieve maximal function within the limitations imposed by the disease and its subsequent treatment.

Beyond the physical challenges of the disease and its subsequent treatment, breast cancer patients experience a variety of emotional reactions and psychological symptoms, which may have a significant impact on quality of life. Symptom relief and health promotion are central in the care of women with breast cancer. The present study may contribute to evidence-based knowledge concerning the efficacy of mindfulness training to support patient empowerment to regain health in a breast cancer disease. If MBSR is effective for symptom relief and quality of life, the method will have significant clinical relevance that may generate standard of care for patients with breast cancer. If so, the method will also be of great benefit to other patient groups. There is a substantial body of research on disease and treatment of severe illness, but very few studies directly examine factors that promote health. MBSR may promote health by engaging and strengthening an individual’s internal resources for optimizing recovery from illness, and it may also improve the ability to cope with mood disturbance and symptoms of stress.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

EKS conceived and conducts this study. EKS, LM and IB contributed to the conception and design of the study. SH provides feedback in each phase of the study. BA carries out the cytometric assays and the immunoassays. AO participated in the design and is responsible for statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Elisabeth Kenne Sarenmalm, Email: elisabeth.kenne.sarenmalm@vgregion.se.

Lena B Mårtensson, Email: lena.martensson@his.se.

Stig B Holmberg, Email: stig.holmberg@vgregion.se.

Bengt A Andersson, Email: bengt.a.andersson@vgregion.se.

Anders Odén, Email: anders.oden@mbox301.swipnet.se.

Ingrid Bergh, Email: ingrid.bergh@his.se.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, Region Västra Götaland, the Research Committee Skaraborg Hospital, and the Skaraborg Research Committee.

We are grateful to Anna-Lena Emanuelsson-Loft for data management. We especially acknowledge the help of the senior MBSR instructor Ola Schenström, specialist in community medicine, and skilled in mindfulness training.

References

- Morasso G, Costantini M, Viterbori P, Bonci F, Del Mastro L, Musso M, Garrone O, Venturini M. Predicting mood disorders in breast cancer patients. Eur J Canc. 2001;37(2):216–223. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmke MM, Brown JK. Predictors of symptom distress in women with breast cancer during the first chemotherapy cycle. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2005;15(4):215–227. doi: 10.5737/1181912x154215220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjerl K, Andersen EW, Keiding N, Mortensen PB, Jorgensen T. Increased incidence of affective disorders, anxiety disorders, and non-natural mortality in women after breast cancer diagnosis: a nation-wide cohort study in Denmark. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105(4):258–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.9028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire P. Managing psychological morbidity in cancer patients. Eur J Canc. 2000;36(5):556–558. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleiker EM, Pouwer F, van der Ploeg HM, Leer JW, Ader HJ. Psychological distress two years after diagnosis of breast cancer: frequency and prediction. Patient Educ Counsel. 2000;40(3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Pozo C, Harris SD, Noriega V, Scheier MF, Robinson DS, Ketcham AS, Moffat FL Jr, Clark KC. How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: a study of women with early stage breast cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65(2):375–390. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epping-Jordan JE, Compas BE, Osowiecki DM, Oppedisano G, Gerhardt C, Primo K, Krag DN. Psychological adjustment in breast cancer: processes of emotional distress. Health Psychol. 1999;18(4):315–326. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrykowski MA, Curran SL, Studts JL, Cunningham L, Carpenter JS, McGrath PC, Sloan DA, Kenady DE. Psychosocial adjustment and quality of life in women with breast cancer and benign breast problems: a controlled comparison. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(8):827–834. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova MJ, Cunningham LL, Carlson CR, Andrykowski MA. Posttraumatic growth following breast cancer: a controlled comparison study. Health Psychol. 2001;20(3):176–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenne Sarenmalm E, Thoren-Jonsson AL, Gaston-Johansson F, Ohlen J. Making sense of living under the shadow of death: adjusting to a recurrent breast cancer illness. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(8):1116–1130. doi: 10.1177/1049732309341728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer A, Salovey P. Psychosocial sequelae of breast cancer and its treatment. Ann Behav Med. 1996;18(2):110–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02909583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Prac Oncol. 2008;5(8):466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz D, Kutz LA, MacCallum R, Courtney ME, Glaser R. Stress and immune responses after surgical treatment for regional breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(1):30–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton LM, Andersen BL, Crespin TR, Carson WE. Individual trajectories in stress covary with immunity during recovery from cancer diagnosis and treatments. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(2):185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltschke C, Krainer M, Budinsky AC, Berger A, Muller C, Zeillinger R, Speiser P, Kubista E, Eibl M, Zielinski CC. Reduced mitogenic stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells as a prognostic parameter for the course of breast cancer: a prospective longitudinal study. Br J Canc. 1995;71(6):1292–1296. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S, Kan N, Harada T, Ichinose Y, Moriguchi Y, Li L, Sugie T, Kodama H, Satoh K, Ohgaki K. Relationship between immunological parameters and survival of patients with liver metastases from breast cancer given immuno-chemotherapy. Breast Canc Res Treat. 1993;26(1):55–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00682700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VS, Dyer CE, Jameel JK, Drew PJ, Greenman J. Potential prognostic and therapeutic roles for cytokines in breast cancer (Review) Oncol Rep. 2006;15(1):179–185. doi: 10.3892/or.15.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoe T, Iino Y, Morishita Y. Trends of IL-6 and IL-8 levels in patients with recurrent breast cancer: preliminary report. Breast Canc (Tokyo, Japan) 2000;7(3):187–190. doi: 10.1007/BF02967458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachelot T, Ray-Coquard I, Menetrier-Caux C, Rastkha M, Duc A, Blay JY. Prognostic value of serum levels of interleukin 6 and of serum and plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in hormone-refractory metastatic breast cancer patients. Br J Canc. 2003;88(11):1721–1726. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado R, Junius S, Benoy I, Van Dam P, Vermeulen P, Van Marck E, Huget P, Dirix LY. Circulating interleukin-6 predicts survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Int J Canc. 2003;103(5):642–646. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW, Arndt LA, Pasnau RO. Critical review of psychosocial interventions in cancer care. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1995;52(2):100–113. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950140018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard T, Maguire P. The effect of psychological interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients: results of two meta-analyses. Br J Canc. 1999;80(11):1770–1780. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(1):7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecken LJ, Compas BE. Stress, coping, and immune function in breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(4):336–344. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2404_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation for everyday life. London: Piatkus; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, Peterson LG, Fletcher KE, Pbert L, Lenderking WR, Santorelli SF. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Am Psychiatr. 1992;149(7):936–943. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plews-Ogan M, Owens JE, Goodman M, Wolfe P, Schorling J. A pilot study evaluating mindfulness-based stress reduction and massage for the management of chronic pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1136–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):613–622. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10(2):125–143. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Ahn SC, Lee YJ, Choi TK, Yook KH, Suh SY. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress management program as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy in patients with anxiety disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(2):189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toneatto T, Nguyen L. Does mindfulness meditation improve anxiety and mood symptoms? A review of the controlled research. Can J Psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2007;52(4):260–266. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witek-Janusek L, Albuquerque K, Chroniak KR, Chroniak C, Durazo-Arvizu R, Mathews HL. Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(6):969–981. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branstrom R, Kvillemo P, Brandberg Y, Moskowitz JT. Self-report mindfulness as a mediator of psychological well-being in a stress reduction intervention for cancer patients–a randomized study. Ann Behav Med. 2010;39(2):151–161. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branstrom R, Kvillemo P, Akerstedt T. Effects of mindfulness training on levels of cortisol in cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(2):158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, Goodey E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):571–581. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000074003.35911.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Speca M, Faris P, Patel KD. One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(8):1038–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, Goodey E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress and levels of cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and melatonin in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(4):448–474. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T, Consort G. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(8):663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, Oxman AD, Moher D. group C. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Bmj. 2008;337:a2390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, Group C. Methods and processes of the CONSORT Group: example of an extension for trials assessing nonpharmacologic treatments. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):W60–W66. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008-w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SBU. Metoder för behandling av långvarig smärta: En systematisk litteraturöversikt. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The Swedish Breast Cancer Group. National Guidelines. Breast Cancer Treatment. 2008. http://www.swebcg.se.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykletun A, Stordal E, Dahl AA. Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: factor structure, item analyses and internal consistency in a large population. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:540–544. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(1):17–41. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mysteries of health: how people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725–733. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M, Lindstrom B. Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(6):460–466. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.018085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langius A, Bjorvell H, Antonovsky A. The sense of coherence concept and its relation to personality traits in Swedish samples. Scand J Caring Sci. 1992;6(3):165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1992.tb00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbar O. Coping with threat. Implications for women with a family history of breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(4):329–339. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(98)71321-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thome B, Hallberg IR. Quality of life in older people with cancer – a gender perspective. Eur J Canc Care. 2004;13(5):454–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2004.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, Lepore JM, Friedlander-Klar H, Kiyasu E, Sobel K, Coyle N, Kemeny N, Norton L. et al. The memorial symptom assessment scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Canc. 1994;30A(9):1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranmer JE, Heyland D, Dudgeon D, Groll D, Squires-Graham M, Coulson K. Measuring the symptom experience of seriously ill cancer and noncancer hospitalized patients near the end of life with the memorial symptom assessment scale. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2003;25(5):420–429. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurny C, Bernhard J, Bacchi M, van Wegberg B, Tomamichel M, Spek U, Coates A, Castiglione M, Goldhirsch A, Senn HJ. et al. The Perceived Adjustment to Chronic Illness Scale (PACIS): a global indicator of coping for operable breast cancer patients in clinical trials. Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) and the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) Support Care Cancer. 1993;1(4):200–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00366447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard J, Thurlimann B, Schmitz SF, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Cavalli F, Morant R, Fey MF, Bonnefoi H, Goldhirsch A, Hurny C. Defining clinical benefit in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer under second-line endocrine treatment: does quality of life matter? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(6):1672–1679. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med care. 1994;32(1):40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE Jr. The Swedish SF-36 health survey--I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1349–1358. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00125-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson LO, Karlsson J, Bengtsson C, Steen B, Sullivan M. The Swedish SF-36 health survey II. Evaluation of clinical validity: results from population studies of elderly and women in Gothenborg. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1095–1103. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J. The Swedish SF-36 health survey III. Evaluation of criterion-based validity: results from normative population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1105–1113. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):455–471. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SG, Cook SL. Are reports of posttraumatic growth positively biased? J Trauma Stress. 2004;17(4):353–358. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000038485.38771.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Personal Data Act. Swedish codes of statues. Min of Justice. 1998;1998:204. [Google Scholar]

- Biobanks in Medical Care Act. Swedish codes of statues. SFS. 2002;2002:297. [Google Scholar]