Summary

Antagonism between growth-promoting and stress-responsive signaling influences tissue homeostasis and longevity in metazoans. The transcription factor FoxO is central to this regulation, affecting cell proliferation, stress responses, apoptosis, and longevity. Insulin/IGF signaling promotes FoxO phosphorylation, causing its interaction with 14-3-3 molecules. The consequences of this interaction for FoxO-induced biological processes and for the regulation of lifespan in higher organisms remain unclear. Significant complexities in the effects of 14-3-3 proteins on lifespan have been uncovered in Caenorhabditis elegans, suggesting both positive and negative roles for 14-3-3 proteins in the control of aging. Using genetic and biochemical studies, we show here that 14-3-3ε antagonizes FoxO function in Drosophila. We find that dFoxO and 14-3-3ε proteins interact in vivo and that this interaction is lost in response to oxidative stress. Loss of 14-3-3ε results in increased stress-induced apoptosis, growth repression and extended lifespan of flies, phenotypes associated with elevated FoxO function. Our results further show that increased expression of 14-3-3ε reverts FoxO-induced growth defects. 14-3-3ε thus serves as a central modulator of FoxO activity in the regulation of growth, cell death and longevity in vivo.

Keywords: 14-3-3, aging, apoptosis, FoxO, insulin signaling, oxidative stress

Introduction

Life expectancy of an organism is influenced by its genetic makeup, as well as by extrinsic parameters, such as nutrition and oxidative stress. Gene regulatory mechanisms that control metabolism or the ability to fend off detrimental reactive oxygen species affect longevity of a wide variety of organisms. Interestingly, it is becoming increasingly apparent that these same signaling mechanisms are compromised in age-related metabolic diseases, such as obesity and diabetes (Tissenbaum & Guarente, 2002; Hekimi & Guarente, 2003; Koubova & Guarente, 2003; Nandi et al., 2004; Guarente & Picard, 2005; Kenyon, 2005; Matsumoto & Accili, 2005).

Extensive work in genetically accessible model organisms indicates a mutual exclusion of anabolic functions, such as growth and proliferation, and longevity-promoting processes (Accili & Arden, 2004; Kenyon, 2005). In recent years, evidence has emerged for a tightly regulated balance between growth signaling through the insulin/IGF signaling (IIS) pathway, and stress resistance and longevity promoted by Jun-N-terminal Kinase (JNK) signaling. In particular, work in worms and flies, as well as in mammalian cell culture, has demonstrated that the Forkhead transcription factor FoxO integrates signals transduced by these evolutionarily conserved pathways (Garofalo, 2002; Ikeya et al., 2002; Rulifson et al., 2002; Essers et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005). According to the current model, FoxO is inactivated by IIS in conditions of high nutrient availability and low environmental stress. In these conditions, the insulin receptor is activated by elevated levels of insulin-like peptides, initiating a signaling cascade that results in activation of the protein kinase Akt (Britton et al., 2002; Rulifson et al., 2002; Goberdhan & Wilson, 2003). Akt phosphorylates FoxO, inducing its interaction with 14-3-3 molecules and causing its cytoplasmic retention (Junger et al., 2003; Puig et al., 2003; Accili & Arden, 2004). IIS activation thus results in repression of FoxO target genes. Reduction of IIS signaling activity, in turn, results in FoxO-mediated growth repression, lifespan extension, and increased tolerance to environmental stress in various model systems (Lin et al., 1997; Ogg et al., 1997; Kenyon, 2001; Bluher et al., 2003; Tatar et al., 2003; Accili & Arden, 2004; Brunet et al., 2004).

In response to stress, activation of JNK results in the nuclear translocation of FoxO, inducing the transcription of genes encoding proteins involved in stress defense, damage repair, apoptosis, and growth inhibition (Jassim et al., 2003; Essers et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2007). Accordingly, increasing JNK activity induces stress tolerance and extends lifespan of flies and worms in a dfoxo-dependent manner (Wang et al., 2003, 2005; Oh et al., 2005). Similarly, dfoxo is required downstream of JNK signaling to induce cell death in response to UV-induced DNA damage (Luo et al., 2007).

14-3-3 molecules are emerging as crucial components of the regulatory mechanism that modulates FoxO function in response to IIS and JNK signaling. Binding of FoxO to 14-3-3 proteins had initially been described in mammalian cell culture studies, where it was found to be dependent on Akt-mediated phosphorylation of FoxO and thought to promote FoxO’s cytoplasmic retention (Brunet et al., 1999, 2002; Obsil et al., 2003; Obsilova et al., 2005). While this model suggested that 14-3-3 interferes with FoxO function, recent studies in C. elegans reveal considerable complexities in the role of 14-3-3 proteins in vivo and suggest that 14-3-3, in addition to acting as an inhibitor of the FoxO homologue DAF-16, might also cooperate with the transcription factor in the nucleus to regulate lifespan (Berdichevsky et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007). It remains unclear whether these complexities are specific for C. elegans, and whether the interaction between FoxO and 14-3-3 also influences stress responses and longevity in other organisms.

Here, we present genetic evidence for a role of 14-3-3 in the control of growth, stress tolerance and longevity of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. Our results suggest that one of the two Drosophila 14-3-3 homologues, 14-3-3ε, binds to dFoxO and inhibits its function to promote growth, but limiting stress-induced apoptosis, overall stress tolerance and lifespan.

Results

14-3-3ε modulates FoxO-mediated apoptosis in the developing retina

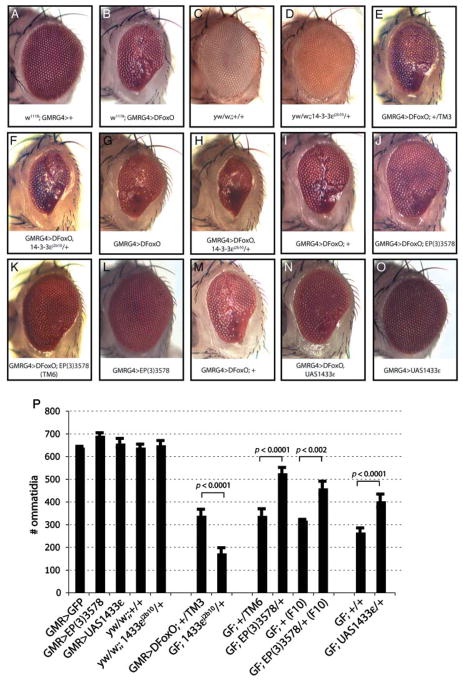

In a screen to identify genes involved in the regulation of FoxO, we found mutations in 14-3-3ε as strong enhancers of FoxO-induced apoptosis in the retina. When FoxO activity is induced in the developing retina, for example by overexpression of dFoxO, excessive apoptosis results in significant ablation of adult ommatidial structures (Fig. 1A,B) (Wang et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2007). We found that this phenotype is strongly enhanced when the 14-3-3ε gene-dose is reduced using a previously described 14-3-3ε loss-of-function allele (14-3-3ε j2b10; Chang & Rubin, 1997) (heterozygotes for 14-3-3ε j2b10 display no eye phenotype in wild-type backgrounds; Fig. 1C–H,P). Supporting a role for 14-3-3ε in limiting FoxO-induced apoptosis in the retina, the retinal FoxO gain-of-function phenotype was suppressed when 14-3-3ε levels were increased by overexpression of 14-3-3ε from an EP element inserted into the 5′ region of 14-3-3ε (EP elements allow Gal4-mediated up-regulation of downstream genes; expression of 14-3-3ε alone in the retina does not affect eye structure; Fig. 1I–L,P) (Rorth et al., 1998) or from a UAS-linked transgenic construct (Fig. 1M–P) (Chen et al., 2003). Gal4-mediated induction of 14-3-3ε in the EP line used here (14-3-3εEP3578) was confirmed using reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Figure S1, Supporting Information).

Fig. 1.

14-3-3ε counteracts dFoxO-mediated apoptosis in the Drosophila retina. (A, B) Overexpression of dFoxO in the retina under the control of GMRGal4 results in excessive apoptosis during retinal development and subsequent ommatidia loss (compare siblings: wild-type, A, with GMRGal4, UASdFoxO, B). (C–H) This phenotype is enhanced when 14-3-3ε is mutated (compare siblings: GMR>dFoxO, E, with GMR>dFoxO; 14-3-3ε j2b10, F, from cross of GMR>dFoxO with 14-3-3ε j2b10/TM3, or siblings: GMR>dFoxo, G, with GMR>dFoxo; 14-3-3ε j2b10, H, from cross of GMR>dFoxO with 10ε backcrossed 14-3-3ε j2b10/+). 14-3-3ε j2b10 heterozygosity does not affect eye structure in a wild-type background (compare siblings: yw/w;;+/+, C, with yw/w; 14-3-3ε j2b10/+, D). (I–O) Conversely, the dFoxO gain-of-function phenotype is reduced when 14-3-3ε is co-expressed (using 14-3-3ε EP3578, compare siblings of cross with backcrossed 14-3-3ε EP3578 line: GMR>dFoxO, I, with GMR>dFoxO; 14-3-3ε EP3578, J. This effect is independent of the genetic background, as seen when experiment is performed with non-backcrossed 14-3-3ε EP3578 line, K). 14-3-3ε overexpression alone does not affect eye structure, L. (M–O) Co-expression of 14-3-3ε using a transgenic UAS-14-3-3ε line confirms the suppression of the dFoxO gain-of-function phenotype by 14-3-3ε (compare siblings: GMR>dFoxO, M, with GMR>dFoxO; UAS14-3-3ε, N). Overexpression of 14-3-3ε in wild-type background does not affect eye structure, O. All crosses were performed at least four times, phenotypes were assessed visually in at least 20 flies of each genotype each time. The penetrance of the observed phenotypes is close to 100%. Representative images are shown here. (P) Intact ommatidia were counted in eyes of flies of the listed genotypes derived from representative crosses. Averages and standard deviations are shown. Student’s t-tests were performed to compare sibling flies (p-values listed, n = 4–5). GMR>Foxo is abbreviated as GF is some cases.

Combined, these genetic interactions suggest that 14-3-3ε is sufficient and required to counteract excessive FoxO activity in the Drosophila retina. Interestingly, the second 14-3-3 gene in Drosophila, 14-3-3ζ, did not interact with FoxO in the retina, indicating functional specificity between these closely related 14-3-3 genes (not shown).

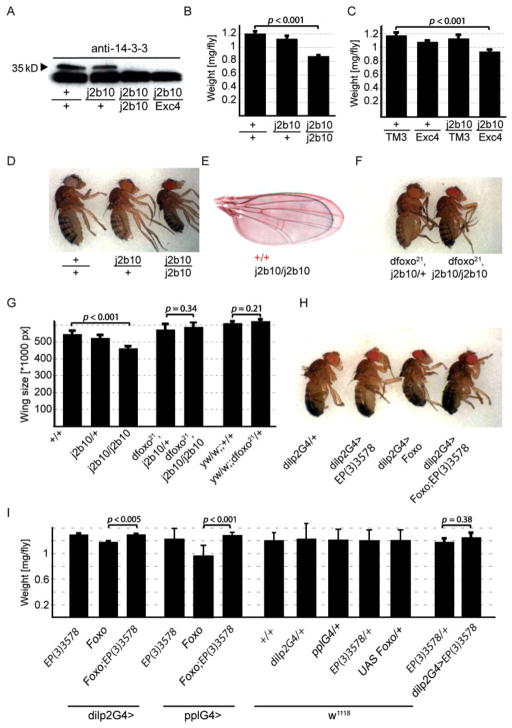

14-3-3ε modulates growth in a FoxO-dependent manner

To further establish whether 14-3-3ε limits FoxO activity in vivo, we analyzed its function in the regulation of body size. Growth regulation is a hallmark of insulin signaling, and increased FoxO activity results in dwarf flies (Junger et al., 2003). To study the role of 14-3-3ε in this paradigm, we backcrossed the 14-3-30ε j2b10 line into the w1118 background for 10 generations, and found that in the resulting fly line a small fraction (> 5%) of flies carrying the j2b10 allele in homozygosity emerged, supporting earlier observations (Chang & Rubin, 1997; Su et al., 2001). The j2b10 allele is caused by a P-element insertion into the first intron of 14-3-3ε. We confirmed the loss of 14-3-3ε protein in the backcrossed line using Western blotting with an antibody raised against the N-terminus of human 14-3-3 β/α (Zymed Laboratories Inc., South San Francisco, CA 94080, USA). This antibody is expected to detect all Drosophila 14-3-3ε and 14-3-3ζ isoforms, and, accordingly, detects at least three bands in fly extracts (the lower molecular weight bands are 14-3-3ζ, as identified by mass spectroscopy, see Fig. 3A). The higher molecular weight band cannot be detected in backcrossed 14-3-3ej2b10 homozygous mutants, nor in transheterozygotes for 14-3-3ε j2b10 and a 14-3-3ε allele generated by imprecise excision of the P-element (14-3-3εexc4) (Chen et al., 2003), confirming the loss of 14-3-3ε in this line (Fig. 2A).

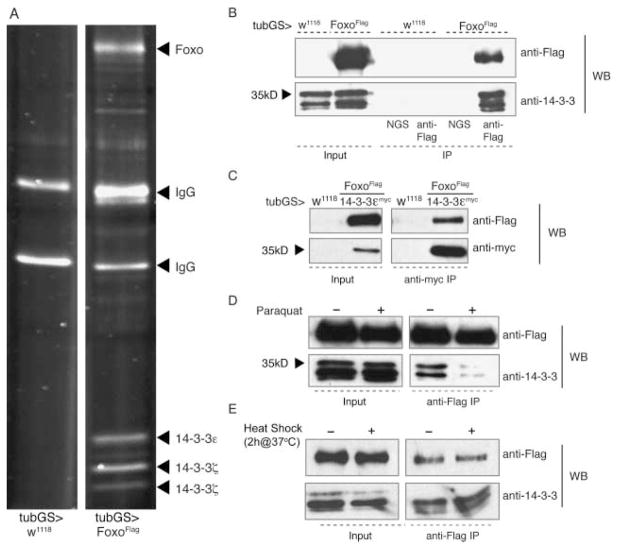

Fig. 3.

Interaction of FoxO with 14-3-3ε. (A) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of FLAG-tagged FoxO from heads of flies ubiquitously expressing FoxO-FLAG under the control of tubGSGal4 (right panel). Control IPs from wild-type flies (tubGSGal4/w1118) show only IgG bands (left panel). The co-precipitating bands around 35 kDa were purified and subjected to mass spectroscopy. The two lower molecular weight bands were identified as 14-3-3ζ. (B–D) Western blots confirming that 14-3-3 molecules co-immunoprecipitate with FLAG-tagged FoxO under normal conditions. Co-precipitation is detected using both anti-FLAG antibodies to precipitate FoxO-FLAG (B, Western detects endogenous 14-3-3), or anti-myc antibodies to precipitate myc-14-3-3ε (C, Western detects FoxO-FLAG). (D) Exposure to Paraquat (20 mM) prior to IP reduces the interaction between FoxO and 14-3-3 molecules. (E) The interaction between FoxO and 14-3-3 molecules is not affected by heat shock. Flies were heat-shocked by incubation at 37 °C for 2 h prior to protein extraction. IPs were performed on head extracts from flies expressing a FLAG-tagged FoxO construct ubiquitously (using the ubiquitous driver tubulin-GeneSwitch Gal4; TubGS) alone or in combination with Myc-tagged 14-3-3ε (in C). Anti-FLAG antibody (or anti-myc in C) was used for IP and blotting was done using anti-FLAG, anti-myc or anti-14-3-3. Normal goat serum was used as IP control. These experiments were repeated at least three times.

Fig. 2.

14-3-3ε regulates body size in flies. (A) Western blot confirming the loss of 14-3-3ε protein in 14-3-3ε j2b10 homozygous flies. Note that the antibody detects multiple 14-3-3 isoforms (see Fig. 3). (B–D) Flies homozygous for the loss-of-function allele 14-3-3ε j2b10 have significantly reduced weight (B; p < 0.001 for j2b10 homozygotes compared to wild type; Student’s t-test; n = 6, 5 and 4 groups of 10 flies for +/+, j2b10/+ and j2b10/j2b10), body size (D) and wing size (E, G) compared to their wild-type and heterozygous siblings. Similar phenotypes are observed in trans-heterozygotes with the loss-of-function allele 14-3-3εexc4 (C; p < 0.001 for j2b10/Exc4 trans-heterozygotes compared to wild type; Student’s t-test; n = 4 groups of 8–10 flies each). (F, G) When the dfoxo gene dose is reduced (using the loss-of-function allele dfoxo21) in flies homozygous for 14-3-3ε j2b10, normal wing and body sizes are restored. Wing size was quantified for sibling progeny of backcrossed w1118; 14-3-3ε j2b10/+ flies (n = 14, 12 and 6 for +/+, j2b10/+ and j2b10/j2b10, respectively). Similarly, wing size of siblings from crosses of yw;; dfoxo21,14-3-3ε j2b10/TM3 with w;;14-3-3ε j2b10/+ was determined (n = 10 for both dfoxo21, j2b10/+ and dfoxo21, j2b10/j2b10). dfoxo21 heterozygosity alone has no effect on growth (siblings of a cross of yw;; dfoxo21/+ with w1118 are compared; n = 11 each). (H, I) 14-3-3ε antagonizes systemic growth repression by dFoxO. Overexpression of dFoxO in insulin-producing cells (using the insulin-like peptide driver, dilp2Gal4) or in fatbody (using the fatbody-specific driver pplGal4) results in growth repression. This phenotype is rescued by co-overexpression of 14-3-3ε (shown in H are body sizes of representative sibling progeny of a cross between dilp2G4/dilp2G4 and UASFoxO/CyO;14-3-3εEP3578/TM3; these crosses were repeated five times). Shown in (I) are weights of sibling progeny of crosses between dilp2G4 or pplGal4 with UASFoxO/CyO;14-3-3εEP3578/TM3. Transgenic driver and UAS lines were generated in and backcrossed into the w1118 genetic background. Controls are from crosses between w1118 and UAS lines or driver lines. No significant weight differences are detected between wild-type flies and any transgenic line. Similar results were obtained in controls outcrossed into the y1w1 genetic background. Overexpression of 14-3-3ε in insulin-producing cells (progeny of cross between dilp2G4/+ and 14-3-3ωEP3578/+) shows slight, but insignificant increase in size in a wild-type background (p = 0.38). Overexpression of 14-3-3ω in fatbody (progeny of cross between pplG4/+ and 14-3-3EP3578/+) shows no significant difference in size (compare pplG4/+ and pplG4/14-3-3EP3578). p-values from Student’s t-test; n between 4 and 8 groups of 10 flies for all cases. All interactions shown here in females were similar in males.

Strikingly, homozygous 14-3-3ε mutants are smaller than their isogenic siblings, as measured by whole body size, body weight, and wing size (Fig. 2B,D,E). We confirmed that loss of 14-3-3ε caused this phenotype by assessing the size of transheterozygotes for 14-3-3ε j2b10 and 14-3-3εexc4 (Fig. 2C). Importantly, the dwarf phenotype of 14-3-3ε mutants was reverted when the dfoxo gene dose was reduced (Fig. 2F,G), indicating that the size defects of 14-3-3ε mutants are a result of excessive FoxO activity.

Furthermore, we asked whether increasing expression levels of 14-3-3ε in insulin-producing cells (IPCs) or fatbody during development would affect body size of the fly. FoxO activity in IPCs negatively affects growth through endocrine mechanisms (Wang et al., 2005). To test whether 14-3-3 activity could affect this function, we overexpressed 14-3-3ε, dfoxo, or both using the IPC-specific dilp2Gal4 driver (Rulifson et al., 2002) and assessed body size and weight (Fig. 2I). Increased 14-3-3ε expression reverted the small size phenotype of flies that over-express dfoxo in IPCs (Fig. 2H,I). Similarly, flies overexpressing dfoxo in the fatbody (using the pplGal4 driver; Zinke et al., 1999) are smaller than their isogenic controls. This phenotype is reverted by co-overexpression of 14-3-3ε (Fig. 2I). These effects confirm that 14-3-3ε can inhibit dFoxO in tissues relevant for endocrine control of growth and longevity of the fly.

Interaction between 14-3-3ε and FoxO in vivo is disrupted by oxidative stress

Our previous studies have demonstrated that dFoxO is activated and translocates to the nucleus in response to stress-induced JNK activation (Wang et al., 2005). The molecular mechanism mediating this activation remains unclear but recent evidence points to 14-3-3 proteins as potential mediators of this interaction (Tsuruta et al., 2004; Sunayama et al., 2005; Yoshida et al., 2005). To test this in vivo, we asked whether dFoxO protein interacts with 14-3-3ε, and whether this interaction would be affected by exposure to oxidative stress. We performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments from fly head extracts using an inducible, ubiquitously expressed FLAG-tagged transgenic dFoxO molecule and analyzed co-precipitation of endogenous proteins by mass spectroscopy. Interestingly, the most prominent interacting partners of dFoxO were 14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3ε (Fig. 3A). We confirmed this interaction by co-immunoprecipitation and Western blotting (Fig. 3B,C) using either anti-FLAG antibodies to precipitate dFoxO-FLAG (Fig. 3B), or anti-myc antibodies to precipitate transgenic myc-14-3-3ε (Fig. 3C).

To test whether the interaction between dFoxO and 14-3-3 molecules is affected by environmental stress, we exposed flies to the oxidative stress-inducing compound Paraquat prior to immuno-precipitating FLAG-tagged dFoxO. Strikingly, we found that under these conditions, the interaction between all 14-3-3 variants and dFoxO was strongly reduced (Fig. 3D). This effect seems to be specific for oxidative stress, as heat shock (2 h at 37 °C) did not affect the interaction between dFoxO and 14-3-3 molecules (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, similar results were obtained in C. elegans in which the interaction between DAF-16 and 14-3-3 was found to be independent of heat stress (Berdichevsky et al., 2006).

These results suggest that a release of dFoxO from its interaction with 14-3-3 is part of the oxidative stress response in flies.

14-3-3ε regulates UV-induced apoptosis

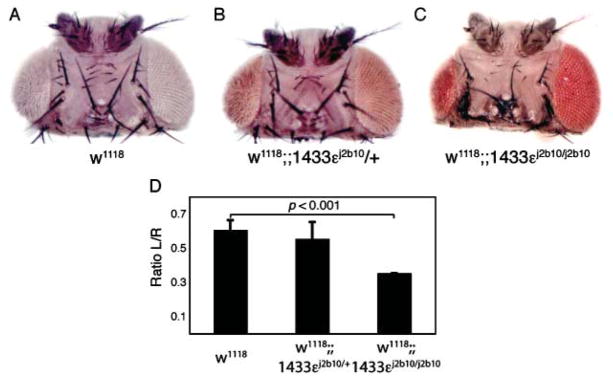

Similar to oxidative stress, UV irradiation can induce FoxO activity, promoting damage repair and apoptosis (Greer & Brunet, 2005). In the developing pupal retina of Drosophila, for example, UV-induced DNA damage activates JNK and promotes FoxO-induced cell death, resulting in loss of adult eye tissue (Jassim et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2007). The extent of tissue loss in the adult reflects the sensitivity of pupal cells to UV irradiation. Thus, after irradiating only one eye, the relative size of irradiated and nonirradiated eyes can serve as a measure for pro-apoptotic FoxO activity in the developing retina. Accordingly, the relative activity of IIS and JNK, as well as the gene-dose of dfoxo, affect UV-induced tissue loss in the retina significantly (Luo et al., 2007). Using this experimental paradigm, we found that 14-3-3ε j2b10 mutants (heterozygous and homozygous) display increased sensitivity to UV-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4), suggesting that FoxO can be activated more readily or more intensely when 14-3-3ε is absent.

Fig. 4.

14-3-3ε regulates UV-induced apoptosis. (A–D) 14-3-3ε j2b10 homozygous mutants (C) exhibit increased apoptosis after UV irradiation compared to their wild-type (A) or heterozygous (B) siblings, as indicated by the reduced size of the left eye in 14-3-3ε j2b10 homozygotes (C). Only the left eye (A–C) was irradiated at 24 h after puparium formation, leaving the right eye as internal control (Jassim et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2007). The ratio of left and right eye sizes was quantified in (D) (p < 0.001 for j2b10 homozygotes compared to wild-type; Student’s t-test; n = 7, 8 and 4 for w1118, j2b10/+ and j2b10/j2b10, respectively).

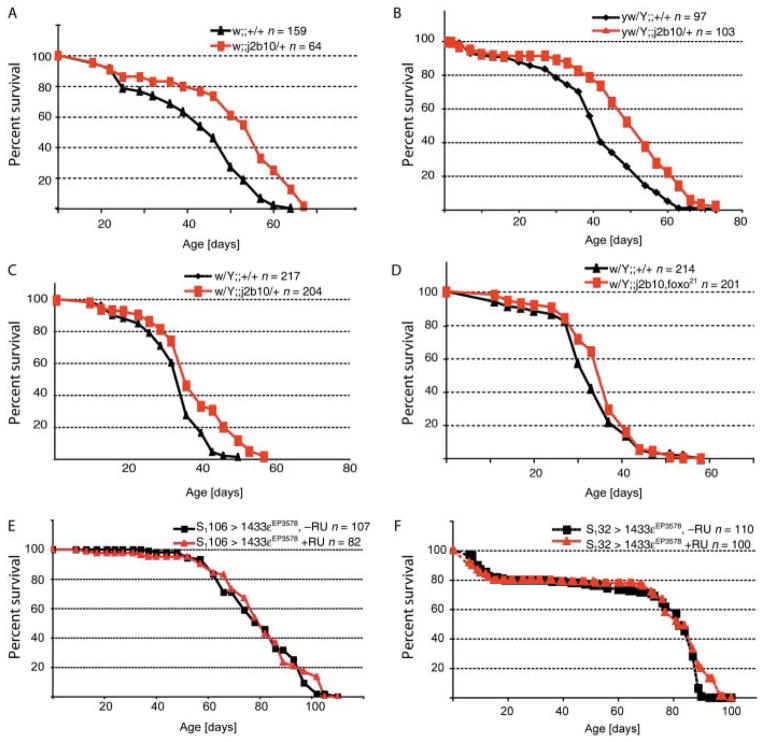

Extended lifespan in 14-3-3ε mutants

These results thus imply that reducing the levels of 14-3-3ε in the fly should result in chronically active dFoxO or sensitize dFoxO to activation by stress. Elevated dFoxO activity extends lifespan in flies (Giannakou et al., 2004; Hwangbo et al., 2004), and 14-3-3ε mutants are thus expected to live longer than iso-genic wild-type controls. To probe this hypothesis, we assessed mortality in populations of sibling flies derived from inbred as well as outbred populations that were wild type or heterozygous for 14-3-3ε j2b10 (Fig. 5; Table S1, Supporting Information). Notably, we found that reducing the gene dose of 14-3-3ε resulted in significant lifespan extension under normal conditions, mimicking the effect of elevated FoxO levels on longevity (Fig. 5A). Mean and maximum lifespan of 14-3-3ε j2b10 heterozygotes was found to be significantly higher than that of sibling controls. This result was further confirmed in control experiments using wild-type and heterozygous siblings for 14-3-3ε j2b10 obtained by outcrossing the 10-times inbred line into the y1w1 genetic background (Fig. 5B). Lifespan of 14-3-3ε j2b10 heterozygotes was also extended in these lines, ruling out inbreeding and genetic background effects, and further supporting a role for 14-3-3ε in limiting longevity in flies. Importantly, we found that the life-extending effect of mutant 14-3-3ε is dependent on FoxO, as the lifespan of dfoxo21/14-3-3ε double-heterozygous flies was similar to wild-type levels (Fig. 5C, Table S1). dfoxo21 heterozygosity does not significantly affect lifespan in a wild-type background (Wang et al., 2005; Table S1).

Fig. 5.

Flies mutant for 14-3-3ε live longer than their isogenic wild-type siblings. (A–F) Survival of sibling flies of the listed genotypes under standardized conditions (yeast and molasses-based food, 25 °C, 65% humidity, 12-h light/dark cycle) was assessed. Only data for male flies are shown here. See Figure S2 (Supporting Information) for females. (A) The 14-3-3ε j2b10 line was backcrossed more than 10 generations into w1118. Survival of males and females of siblings emerged from a large w1118;;14-3-3ε j2b10/+ population was recorded. Results for one of several experiments are presented here (see Table S1; difference in lifespan is statistically significant, p < 0.001, log rank test). (B) To exclude potential inbreeding effects on the lifespan of tested animals, the isogenic line was outcrossed into the y1w1 background. Lifespan of F1 siblings emerging from this cross is shown (difference in lifespan is statistically significant, p < 0.001, log rank test). (C, D) The lifespan-extending effect of loss of 14-3-3ε requires dFoxO. dfoxo21,14-3-3ε j2b10 recombinants were generated in the y1w1 genetic background using 10× backcrossed w1118;;14-3-3ε j2b10 and 2× backcrossed y1w1;; dfoxo21 flies. Double-heterozygous recombinant males were outcrossed to w1118 twice, and lifespan of sibling male progeny was recorded and is shown in (D). Double mutants (14-3-3ε j2b10, dfoxo21) have no significantly increased longevity over wild-type controls. This contrasts with lifespan differences of sibling progeny of 10× backcrossed w1118;;14-3-3j2b10 flies that were outcrossed into y1w1 once (C). y1w1/Y;;14-3-3j2b10/+ males were crossed to w1118 and lifespan of sibling progeny was recorded here (see also Table S1). (D, E) Overexpression of 14-3-3ε in the abdominal or head fatbodies using the RU486-inducible drivers S1106 or S132, respectively, does not significantly affect lifespan. Flies of the listed genotypes were reared on RU486 (200 μM) or standard control food, and survival was recorded.

We further tested whether lifespan of flies is affected by overexpression of 14-3-3ε in adipose tissue, where dFoxO overexpression extends lifespan (Giannakou et al., 2004; Hwangbo et al., 2004). Interestingly, no effect on lifespan was observed, suggesting that endogenous FoxO activity in this tissue is low under normal conditions (Fig. 5D–E, Table S1).

Discussion

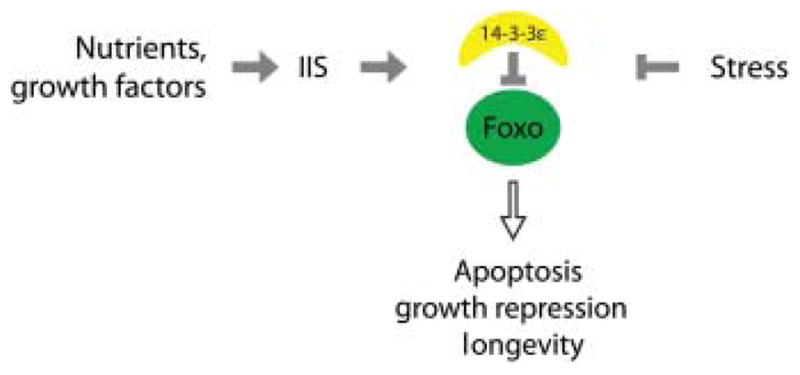

Our results provide genetic evidence that 14-3-3ε antagonizes dFoxO function in the regulation of growth, cell death and aging in flies (Fig. 6). Our data show that wild-type levels of 14-3-3ε are required to keep dFoxO activity at bay, resulting in dFoxO-mediated growth defects when 14-3-3ε is mutated. Interestingly, we find that dFoxO interacts with 14-3-3ε, and that this interaction is lost in response to oxidative stress, but not to heat shock. Furthermore, 14-3-3ε limits dFoxO-induced apoptosis in response to DNA damage in the developing eye. This suggests that 14-3-3ε plays a crucial role in balancing dFoxO activity in vivo, thus influencing the decision between cell death and repair of damaged cells. Accordingly, we find that reducing the 14-3-3ε gene dose is sufficient to promote longevity in flies and that this lifespan extension requires dFoxO function.

Fig. 6.

14-3-3ε as a modulator of signal integration by FoxO. Our data support a model in which, under normal, nutrient-rich conditions, FoxO is inhibited by 14-3-3 in response to Akt-mediated phosphorylation. Upon stress, however, FoxO is released from 14-3-3, allowing the transcriptional induction of stress response genes, pro-apoptotic genes and growth repressors. The combination of FoxO-mediated damage repair and apoptotic removal of damaged cells is expected to cause the observed increase in lifespan.

14-3-3 and the mechanism(s) of cross-talk between JNK and IIS pathways

The regulation of FoxO function in response to stress and/or nutritional cues is complex. A physical interaction between FoxO homologues and 14-3-3 proteins, promoted by Akt-induced phosphorylation of FoxO, has been reported in mammalian tissue culture studies (Brunet et al., 1999, 2002) and in C. elegans (Berdichevsky et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007). Our findings confirm this interaction in flies and show further that it can be disrupted by oxidative stress. The activation of JNK by oxidative stress may account for this disruption, since recent findings from mammalian cell culture systems show that JNK can phosphorylate 14-3-3 molecules, resulting in the release of their binding partners (Tsuruta et al., 2004; Sunayama et al., 2005; Yoshida et al., 2005). JNK activation can promote nuclear translocation of FoxO even in insulin signaling gain-of-function conditions, further suggesting that JNK can interfere with 14-3-3/FoxO binding (Oh et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005). Interestingly, the reported JNK phosphorylation site on 14-3-3 is conserved between vertebrates and flies. While JNK-mediated release of FoxO from its interaction with 14-3-3 is thus a plausible mechanism for JNK/IIS cross-talk, other models cannot be ruled out. Two mechanisms described in vertebrates involve JNK-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate, IRS-1 (Hirosumi et al., 2002) as well as direct phosphorylation of FoxO by JNK (Essers et al., 2004). The finding that the interaction between dFoxO and 14-3-3ε is influenced by oxidative stress but not by heat shock further suggests stress-specific signaling pathways as regulators of the 14-3-3ε/dFoxO interaction. Additional work is needed to evaluate the significance of these distinct signaling mechanisms for the regulation of FoxO function in vivo.

14-3-3/FoxO interaction in the regulation of stress response and lifespan

The role of the interaction between 14-3-3 and FoxO in the regulation of stress defense, growth control, and longevity of the organism is only beginning to be understood. Recently reported data from C. elegans demonstrate a complex role for 14-3-3 in the regulation of stress responses and lifespan (Berdichevsky et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007). As observed in these studies, 14-3-3 appears to be able to play both positive and negative roles in stress tolerance and longevity, extending lifespan when overexpressed (Wang et al., 2006) as well as in Sir2 gain-of-function conditions (Berdichevsky et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006), while inhibiting FoxO/DAF-16-induced dauer formation (Li et al., 2007). To resolve this seeming conflict, parallel pathways have been proposed in which 14-3-3 molecules are required in complex with Sir2 for the activation of nuclear FoxO/DAF-16 upon stress, while retaining inactive FoxO/DAF-16 in the cytoplasm under high insulin signaling conditions (Berdichevsky et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007). Our results suggest that in Drosophila a simple antagonistic model for the 14-3-3ε/FoxO interaction in the regulation of growth, stress response and longevity applies. Thus, loss of 14-3-3ε, and consequent chronic activation of FoxO, results in smaller flies that live longer, while overexpression of 14-3-3ε does not significantly affect lifespan.

A potential explanation for this discrepancy between the observed effects of 14-3-3 in Drosophila and C. elegans is that different 14-3-3 isoforms may have evolved to assume distinct functions in higher metazoans. Accordingly, our co-immuno-precipitation results show that dFoxO interacts with both 14-3-3ε and 14-3-3ζ. We could, however, only detect genetic interactions between 14-3-3ε mutants and dfoxo. Additional studies are required to test a potential function for 14-3-3ζ in the regulation of lifespan by Drosophila Sir2 and dFoxO. It is further possible that the interaction between 14-3-3 proteins and dFoxO in distinct tissues has specific effects on lifespan and stress resistance. Thus, while we show that system-wide reduction of the 14-3-3ε genedose extends lifespan in flies, we have focused our overexpression studies on fatbody-specific drivers, which were used previously to show that increased expression of dFoxO extends lifespan (Giannakou et al., 2004; Hwangbo et al., 2004). We thus cannot rule out that overexpression of 14-3-3ε in other tissues might positively influence longevity. Further studies will be needed to address this question.

The emerging central role of 14-3-3 proteins in the regulation of JNK/IIS cross-talk in a range of model systems further strengthens the notion that genes and mechanisms that control the cellular integration and interpretation of stress response and anabolic pathways are crucial determinants of longevity. Importantly, misregulation of these same signaling nodes in humans is central to the etiology of age-related diseases, such as type II diabetes and cancer.

Experimental procedures

Fly lines

The following fly lines were used in this study: w; UASmyc14-3-3εD/CyO and 14-3-3ε Exc4/TM3 were generously provided by Dr Makis Skoulakis. y1w*;;14-3-3ε j2b10/TM3, w1118;;14-3-3εEP3578/TM6B, and y1w1 were obtained from the Bloomington stock center. pplGal4 was a gift from Dr Pierre Léopold. Dilp2-Gal4 was a gift from Dr Eric Rulifson. TubG4GeneSwitch (tubGS) was a gift from Dr Scott Pletcher. GMRGal4 was a gift from Dr Marek Mlodzik. Flies carrying a UAS-linked FLAG-tagged FoxO were generated by P-element transformation. The FoxO open reading frame was subcloned from a pMT-FoxO construct (gift from Dr Oscar Puig) into a pUAST-3xFLAG vector (gift from Dr Gerasimos Sykiotis and Dr Dirk Bohmann).

The w; UASmyc14-3-3εD/Cyo, y1w*;;14-3-3εj2b10/TM3, and w1118;;14-3-3εEP3578/TM6B were backcrossed more than 10×into the w1118 background. Backcrossed 14-3-3εj2b10/+ and 3×backcrossed y1w1;; dfoxo21/+ were used for the generation of recombinant y1w1;; dfoxo21,14-3-3εj2b10/TM3 flies. Gal4 driver lines were kept in the w1118 genetic background.

Crosses, characterization and quantification of the eye phenotype

Virgin GMRGal4-GFP or GMRGal4, UASFoxo/CyO were crossed to males of either of the genotypes listed in Fig. 2. All crosses were reared at 25 °C in vials on standard cornmeal and molasses-based food.

Heads of the progeny were mounted on agar plates and one eye of each fly was photographed. The total number of intact ommatidia were counted and compared between siblings emerged from the same culture. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Growth measurements

Flies were reared at 25 °C in bottles on standard cornmeal and molasses-based food at controlled larval densities and collected 1 day after emergence. After 2 days in vials with fresh food, the flies were separated by genotype and gender and weighed in pools of 10. Wings were mounted in Canada Balsam (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The wing area was assessed using Adobe Photoshop histogram analysis. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. Only sibling flies emerged from the same vials were compared in these experiments.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

For embryonic RNA, armG4 females were crossed with 14-3-3εEP3578/TM6 or w1118 males and allowed to lay eggs o/n for 16 h at 25 °C on apple plates and embryos were collected. For adult head RNA, 10 heads of adult flies were used. For eye imaginal disc RNA, 20 eye imaginal discs per genotype were dissected from wandering third instar larvae of progeny from crosses of GMRG4 females with 14-3-3εEP3578/TM6 or w1118 males. The tubby marker on TM6 was used for larval genotyping.

RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized from 5 μg of RNA using Superscript Reverse Transcritpase II (Invitrogen). ExTaq (TaKaRa, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) was used for semiquantitative PCR. Primers were 14-3-3 (sense 5′-TGTACAAGGCAAAGCTGGC-3′ and antisense 5′-TTCTCTGCCGCATCCTTG-3′) and rp49 (sense 5′-CGGCACTCGCACATCATT-3′ and antisense 5′-AGCTGTCGCACAAATGGC-3′) as internal control.

Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green and Invitrogen Taq Polymerase on a Bio-Rad MyiQ Detection System (Hercules, CA, USA). All reactions were done in triplicates and normalized to rp49 as internal control as well as to the expression levels of wild-type control material.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Four- to 5-day-old flies ubiquitously overexpressing FLAG-tagged FoxO alone or together with Myc-tagged 14-3-3ε, in response to RU486 (genotypes: w; UASFoxO-FLAG; TubGS and w; UASFoxO-FLAG; TubGS/UASmyc14-3-3ε) were fed 14 h on filters soaked with 1 mM RU486 in 5% sucrose solution (± 20 mM Paraquat). For heat shock, 3-day-old flies were transferred to RU486 containing food (0.2 mM) overnight and subsequently transferred to 37 °C for 2 h.

Cohorts of 50 flies were frozen at −80 °C and heads were subsequently separated and collected on dry ice. Extracts were generated by crushing the heads in 300 μL of lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7,5, 60 mM NaCl2, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.2% Nonidet NP-40, 0.2% Triton X-100, 10% Glycerol, 1 mM DTT) containing PMSF and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The centrifuge-cleared extracts were incubated 4 h at 4 °C with 2 μg of anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma, monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody, product code F 1804) or 2 μg of anti-myc (clone 9E10, Upstate, Lake Placid, NY, #05-419) before the addition of 30 μL prewashed ProteinA Sepharose beads (Sigma) for overnight incubation. The beads were then washed 3× in cold lysis buffer before boiling in sample buffer. Proteins were resolved using SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, and detected by Western blotting using anti-FLAG (M2 antibody, Sigma, dilution 1: 5000), anti-myc (clone 9E10, Upstate; dilution 1: 1000) or anti-14-3-3 antibodies (rabbit polyclonal anti-14-3-3 antibody, Zymed, cat. no. 51-0700; dilution 1: 500).

Mass spectrometric identification of proteins

Single gel bands were extracted and processed separately for tryptic digestion and applied to a microliquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry system (mLC-MS/MS) for peptide analysis. The MS/MS spectra were database searched (sequence) using SEAQUEST (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA, USA). The MS/MS spectra were searched against a downloaded nonredundant Drosophila proteome sequence database from European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/IPI/IPIdrosophila.html).

UV irradiation

The UV treatment and assessment of apoptosis in pupal eyes was conducted as described earlier (Luo et al., 2007). Briefly, mid-aged pupae (24-h after puparium formation) were collected and the pupal shell surrounding the head area was removed. UV irradiation was carried out on pupae that were immobilized on the side, so that only one retina was exposed to UV. A UV-crosslinker (Stratalinker 1800, La Jolla, CA) was used with energy set at 5 mJ cm−2. After irradiation, pupae were kept in the dark until being processed. Quantification of eye size was performed using Photoshop and ratios between the area of irradiated and nonirradiated eyes were determined.

Lifespan analyses

Parental crosses (see Fig. 5 legend for genotypes) were reared at equal density in bottles with standard food. Progeny was collected and transferred to fresh bottles upon emergence and mated for 3 days before separation into cohorts based on genotypes and sexes. Cohorts of 100–200 flies were transferred to empty bottles fitted with a foam plug allowing access to a vial containing standard (yeast and molasses-based) food. The vial was changed every 3–4 days and the number of dead flies was assessed.

For overexpression studies, food was supplemented with 200 μM RU486 or corresponding amounts of carrier (80% EtOH) as control. The effectiveness of RU486-supplemented food to induce transgene expression was regularly tested using UAS-GFP as reporter.

Statistical analysis was performed using the JMP software package.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Dirk Bohmann for critical comments on the manuscript. We further thank Drs M. Skoulakis, E. Rulifson, S. Pletcher, M. Mlodzik, O. Puig, G. Sykiotis, P. Léopold and H. Keshishian for fly lines and reagents. This work was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation (to M.D.N.) and from the National Institutes of Health (to H.J.; R01 AG026691 and R01 AG028127).

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Figure S1 Characterization of 14-3-3εEP3578. (A) Representation of the 14-3-3ε locus. The EP-element causing the 14-3-3εEP3578 allele is shown. It is inserted 5′ of the translation start site. (B, C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR (B) and real-time RT-PCR (C) confirming 14-3-3ε overexpression using the 14-3-3εEP3578 line. RNA was obtained from armGal4,+ and armGal4, 14-3-3εEP3578 embryos, and from GMRGal4,+ and GMRGal4, 14-3-3εEP3578 third instar eye imaginal discs or adult heads. Ribosomal protein 49 (rp49) served as internal control.

Figure S2 Survival of females. Lifespan trajectories of female siblings of the populations shown in Fig. 5 are shown here.

Table S1 Summary of lifespan data.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the Aging Cell Central Office.

References

- Accili D, Arden KC. FoxOs at the crossroads of cellular metabolism, differentiation, and transformation. Cell. 2004;117:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdichevsky A, Viswanathan M, Horvitz HR, Guarente L. C. elegans SIR-2.1 interacts with 14-3-3 proteins to activate DAF-16 and extend life span. Cell. 2006;125:1165–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluher M, Kahn BB, Kahn CR. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science. 2003;299:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1078223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JS, Lockwood WK, Li L, Cohen SM, Edgar BA. Drosophila’s insulin/PI3-kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Dev Cell. 2002;2:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Kanai F, Stehn J, Xu J, Sarbassova D, Frangioni JV, Dalal SN, DeCaprio JA, Greenberg ME, Yaffe MB. 14-3-3 transits to the nucleus and participates in dynamic nucleocytoplasmic transport. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:817–828. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavsky R, Cohen HY, Hu LS, Cheng HL, Jedrychowski MP, Gygi SP, Sinclair DA, Alt FW, Greenberg ME. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HC, Rubin GM. 14-3-3 epsilon positively regulates Ras-mediated signaling in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1132–1139. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.9.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HK, Fernandez-Funez P, Acevedo SF, Lam YC, Kaytor MD, Fernandez MH, Aitken A, Skoulakis EM, Orr HT, Botas J, Zoghbi HY. Interaction of Akt-phosphorylated ataxin-1 with 14-3-3 mediates neurodegeneration in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Cell. 2003;113:457–468. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers MA, Weijzen S, de Vries-Smits AM, Saarloos I, de Ruiter ND, Bos JL, Burgering BM. FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J. 2004;23:4802–4812. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo RS. Genetic analysis of insulin signaling in Drosophila. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:156–162. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakou ME, Goss M, Junger MA, Hafen E, Leevers SJ, Partridge L. Long-lived Drosophila with overexpressed dFOXO in adult fat body. Science. 2004;305:361. doi: 10.1126/science.1098219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goberdhan DC, Wilson C. The functions of insulin signaling: size isn’t everything, even in Drosophila. Differentiation. 2003;71:375–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.7107001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 2005;24:7410–7425. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L, Picard F. Calorie restriction – the SIR2 connection. Cell. 2005;120:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hekimi S, Guarente L. Genetics and the specificity of the aging process. Science. 2003;299:1351–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.1082358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Gorgun CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, Karin M, Hotamisligil GS. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature. 2002;420:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwangbo DS, Gersham B, Tu MP, Palmer M, Tatar M. Drosophila dFOXO controls lifespan and regulates insulin signalling in brain and fat body. Nature. 2004;429:562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature02549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya T, Galic M, Belawat P, Nairz K, Hafen E. Nutrient-dependent expression of insulin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1293–1300. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassim OW, Fink JL, Cagan RL. Dmp53 protects the Drosophila retina during a developmentally regulated DNA damage response. EMBO J. 2003;22:5622–5632. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junger MA, Rintelen F, Stocker H, Wasserman JD, Vegh M, Radimerski T, Greenberg ME, Hafen E. The Drosophila Forkhead transcription factor FOXO mediates the reduction in cell number associated with reduced insulin signaling. J Biol. 2003;2:20. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C. A conserved regulatory system for aging. Cell. 2001;105:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C. The plasticity of aging: insights from long-lived mutants. Cell. 2005;120:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koubova J, Guarente L. How does calorie restriction work? Genes Dev. 2003;17:313–321. doi: 10.1101/gad.1052903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Tewari M, Vidal M, Lee SS. The 14-3-3 protein FTT-2 regulates DAF-16 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2007;301:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Dorman JB, Rodan A, Kenyon C. Daf-16: an HNF-3/forkhead family member that can function to double the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;278:1319–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Puig O, Hyun J, Bohmann D, Jasper H. Foxo and Fos regulate the decision between cell death and survival in response to UV irradiation. EMBO J. 2007;26:380–390. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Accili D. All roads lead to FoxO. Cell Metab. 2005;1:215–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A, Kitamura Y, Kahn CR, Accili D. Mouse models of insulin resistance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:623–647. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obsil T, Ghirlando R, Anderson DE, Hickman AB, Dyda F. Two 14-3-3 binding motifs are required for stable association of Forkhead transcription factor FOXO4 with 14-3-3 proteins and inhibition of DNA binding. Biochemistry. 2003;42:15264–15272. doi: 10.1021/bi0352724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obsilova V, Vecer J, Herman P, Pabianova A, Sulc M, Teisinger J, Boura E, Obsil T. 14-3-3 Protein interacts with nuclear localization sequence of forkhead transcription factor FoxO4. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11608–11617. doi: 10.1021/bi050618r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg S, Paradis S, Gottlieb S, Patterson GI, Lee L, Tissenbaum HA, Ruvkun G. The Fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature. 1997;389:994–999. doi: 10.1038/40194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SW, Mukhopadhyay A, Svrzikapa N, Jiang F, Davis RJ, Tissenbaum HA. JNK regulates lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans by modulating nuclear translocation of forkhead transcription factor/DAF-16. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4494–4499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500749102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig O, Marr MT, Ruhf ML, Tjian R. Control of cell number by Drosophila FOXO: downstream and feedback regulation of the insulin receptor pathway. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2006–2020. doi: 10.1101/gad.1098703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth P, Szabo K, Bailey A, Laverty T, Rehm J, Rubin GM, Weigmann K, Milan M, Benes V, Ansorge W, Cohen SM. Systematic gain-of-function genetics in Drosophila. Development. 1998;125:1049–1057. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulifson EJ, Kim SK, Nusse R. Ablation of insulin-producing neurons in flies: growth and diabetic phenotypes. Science. 2002;296:1118–1120. doi: 10.1126/science.1070058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su TT, Parry DH, Donahoe B, Chien CT, O’Farrell PH, Purdy A. Cell cycle roles for two 14-3-3 proteins during Drosophila development. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3445–3454. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.19.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunayama J, Tsuruta F, Masuyama N, Gotoh Y. JNK antagonizes Akt-mediated survival signals by phosphorylating 14-3-3. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:295–304. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M, Bartke A, Antebi A. The endocrine regulation of aging by insulin-like signals. Science. 2003;299:1346–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1081447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L. Model organisms as a guide to mammalian aging. Dev Cell. 2002;2:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruta F, Sunayama J, Mori Y, Hattori S, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y, Yoshioka K, Masuyama N, Gotoh Y. JNK promotes Bax translocation to mitochondria through phosphorylation of 14-3-3 proteins. EMBO J. 2004;23:1889–1899. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MC, Bohmann D, Jasper H. JNK signaling confers tolerance to oxidative stress and extends lifespan in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2003;5:811–816. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MC, Bohmann D, Jasper H. JNK extends life span and limits growth by antagonizing cellular and organism-wide responses to insulin signaling. Cell. 2005;121:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Oh SW, Deplancke B, Luo J, Walhout AJ, Tissenbaum HA. C. elegans 14-3-3 proteins regulate life span and interact with SIR-2.1 and DAF-16/FOXO. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:741–747. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Yamaguchi T, Natsume T, Kufe D, Miki Y. JNK phosphorylation of 14-3-3 proteins regulates nuclear targeting of cAbl in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:278–285. doi: 10.1038/ncb1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinke I, Kirchner C, Chao LC, Tetzlaff MT, Pankratz MJ. Suppression of food intake and growth by amino acids in Drosophila: the role of pumpless, a fat body expressed gene with homology to vertebrate glycine cleavage system. Development. 1999;126:5275–5284. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.