Abstract

Background

After treatment, patients with active cancer face a considerable burden from the effects of both the disease and its treatment. The Palliative Rehabilitation Program (prp) is designed to ameliorate disease effects and to improve the patient’s functioning. The present study evaluated predictors of program completion and changes in functioning, symptoms, and well-being after the program.

Methods

The program received referrals for 173 patients who had finished anticancer therapy. Of those 173 patients, 116 with advanced cancer were eligible and enrolled in the 8-week interprofessional prp; 67 completed it. Measures of physical, nutritional, social, and psychological functioning were evaluated at entry to the program and at completion.

Results

Participants experienced significant improvements in physical performance (p < 0.000), nutrition (p = 0.001), symptom severity (p = 0.005 to 0.001), symptom interference with functioning (p = 0.003 to 0.001), fatigue (p = 0.001), and physical endurance, mobility, and balance or function (p = 0.001 to 0.001).

Reasons that participants did not complete the prp were disease progression, geographic inaccessibility, being too well (program not challenging enough), death, and personal or unknown reasons. A normal level of C-reactive protein (<10 mg/L, p = 0.029) was a predictor of program completion.

Conclusions

Patients living with advanced cancers who underwent the interprofessional prp experienced significant improvement in functioning across several domains. Program completion can be predicted by a normal level of C-reactive protein.

Keywords: Cancer, interprofessional, palliative care, rehabilitation

1. INTRODUCTION

Many patients who have undergone cancer treatment can be limited in their activities of daily life by the symptoms caused by their disease or its treatment1,2. Cancer rehabilitation is a process that assists the individual’s physical, social, psychological, and vocational functioning within their limits1. Post-treatment rehabilitation has been shown to improve physical symptoms (such as fatigue and physical endurance3,4), nutritional symptoms (such as poor appetite, unintentional weight loss, and nutritional deterioration5,6), psychological symptoms (such as anxiety, depression, and nervousness3,7), and overall quality of life4. Qualitatively, patients who had attended a cancer rehabilitation program stated that rehabilitation was an important stepping stone and that physical and psychosocial care had been an important combination in their recovery8. However, the above-mentioned benefits vary by disease stage9, and research in patients with incurable advanced disease (palliative care patients) is sparse10.

Our team and others have shown evidence of benefit for treatment of symptoms by disease site, such as gastrointestinal or head-and-neck3,5,11, colorectal12, prostate13, breast14,15, and central nervous system sites16. There is also evidence for the successful treatment of symptoms by various professional disciplines, including occupational therapy17, physical therapy18, nursing19, social work20, and dietetics21. However, a combined interprofessional approach remains rare.

Compared with standard oncology care alone, early palliative care is associated with improved mood and quality of life, fewer aggressive oncology treatments at end of life, and extended survival in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer22. The Ottawa Palliative Rehabilitation Program (prp) at Élisabeth Bruyère Hospital in Ottawa, Ontario, is a unique interprofessional program of palliative oncology rehabilitation. In accordance with the World Health Organization’s definition of palliative care23, the goal of the prp team is to empower individuals who are experiencing loss of function, fatigue, malnutrition, psychological distress, or other symptoms as a result of cancer or its treatment. The program is designed to help patients with life-limiting disease, even though the disease is incurable, and to improve their quality of life by enhancing their overall health condition through exercise, good nutrition, individualized psychosocial care, and management of medical complications. It aims to keep people as active as possible in daily life for as long as possible. The clinical expertise of the 6 team members are combined to target each patient’s specific problems by meticulously assessing individual needs so as to properly diagnose and treat their symptom burden1,3,11,17,20,24.

The present exploratory study had the primary objective of estimating the effect of the prp on the physical, nutritional, social, and psychological functioning of patients with advanced cancer who have already completed anticancer treatment. The hypothesis was that patients who complete the prp will improve in the various domains of functioning. The secondary objective was to determine medical factors associated with program completion. The hypothesis was that completing the prp can be predicted by baseline medical variables [pulse, white blood cell (wbc) count, serum C-reactive protein (crp), and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ecog) performance status (ps)].

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Participants

Patient referrals were received from health care professionals in the Ottawa region. Eligible patients were 18 years of age or older, with geographic accessibility, advanced disease, and an ecog ps of 3 or better or a Palliative Performance Scale of more than 50%. Enrolled patients had already completed anticancer treatment.

Patients had to be medically stable and motivated to participate in the nutritional and physical program. Symptoms such as pain, anxiety, depression, nausea, weight loss, fatigue, or weakness from the disease or its treatment had to be present and interfering with functioning in everyday life. Patients were considered ineligible if they had severe cognitive impairment that would interfere with participation or if they did not meet the defined criteria. Some exceptions were made for patients with localized disease who were allowed into the program. The latter patients were not included in the analysis. All patients signed an informed consent to participate. The study was approved by the local research ethics board.

2.2. Assessment and Intervention

Patients underwent a 3-hour initial assessment; they met with each member of the team (physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker, dietician, nurse, physician) individually for 30 minutes. Each clinician obtained baseline measures through self-report questionnaires (which the patient had received in the mail before the visit) and their own clinical measurements.

After the initial assessments, the team met to discuss whether patients were eligible for and could benefit from the program. If so, the team jointly formulated a tailor-made care plan for each patient. Plans included medical and nursing assessments, physical exercise, and occupational, dietary, and psychosocial interventions. Patients accepted into the 8-week program attended group exercise sessions at a gymnasium in the hospital twice weekly. The gym sessions each accommodated 4–5 patients, supervised by the physiotherapist. Before each gym session, patients were seen by other team members as required, according to need, or as requested by the patient. At the end of the prp, final assessments identical to the initial assessments were conducted by each team member. Patients were then discharged back to the referring or family physician and were connected to appropriate community resources. A discharge summary with recommendations for follow-up was provided to the referring and family physicians.

2.3. Outcome Measures

Several outcome measures were used, including 8 self-report questionnaires and several standardized clinical assessments performed by team members. The outcome measures were completed at the beginning of the prp (baseline) and again at completion of the 8-week program (end).

2.3.1. Self-Report Questionnaires

The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (esas) assesses the severity of 9 common symptoms experienced by cancer patients in palliative care. A higher score indicates worse severity of a given symptom25. Early during the study, patients in the prp completed the esas only at the beginning and end of the 8-week program; later, patients completed it at each visit. Because weekly completion did not apply to the full cohort of patients in the study, only the baseline and end esas scores were analyzed.

The MD Anderson Symptom Index assesses interference in patient functioning in 6 domains: general activity, mood, work (including housework), relations with others, walking, and enjoyment of life. Higher sores indicate more interference26.

The Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment is a nutrition assessment tool, validated for clinical and research use with cancer patients. Higher scores indicate higher nutritional risk27,28.

The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory assesses 5 domains of fatigue: general, physical, mental, decreased motivation, and decreased activity29. Higher scores indicate greater fatigue.

2.3.2. Physiotherapy Measures

The physiotherapy assessments of the patients included the Berg Balance Scale30, the Functional Reach Test (balance and function)31, the Timed Up and Go (mobility)32, a grip test (muscle strength)33, and the Six Minute Walk Test (endurance)30,31.

2.3.3. Nurse and Physician

Patients underwent a full clinical examination, with recording of their ecog ps, an objective measure of functional ability (0 = no functional limitations; 4 = confined to bed34).

2.3.4. Laboratory Tests

Blood tests were performed as part of usual clinical care and included full blood count, electrolytes, serum C-reactive protein (crp), serum albumin, thyroid-stimulating hormone, glucose, and lactate dehydrogenase.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using the SPSS software application (version 20: SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Descriptive statistics were used for patient characteristics, grouped according to whether they started and completed the program. Inferential statistics were used to assess changes from baseline to prp end and to examine baseline medical variables that might predict prp completion. Pre–post changes were analyzed using paired-sample t-tests unless the distribution of the difference scores was not normal (3 standard deviations or more for skewness or kurtosis), in which case a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. Missing values were excluded case-wise. Because of the number of pre–post tests, a p value of 0.005 or less was used to determine statistical significance. The Cohen d effect size was used to assess the magnitude of the differences in pre–post measurements unless the distribution was not normal. In such cases, the formula

was used. Medical differences between groups were analyzed using a backward-selection Wald logistic regression. The variables included were crp and wbc count measured in the blood tests, pulse as assessed by the nurse, and ecog ps as assessed by the nurse and physician. Serum crp was dichotomized as either normal (<10 mg/L) or elevated (≥10 mg/L) because of a positively skewed distribution and for clinical utility.

3. RESULTS

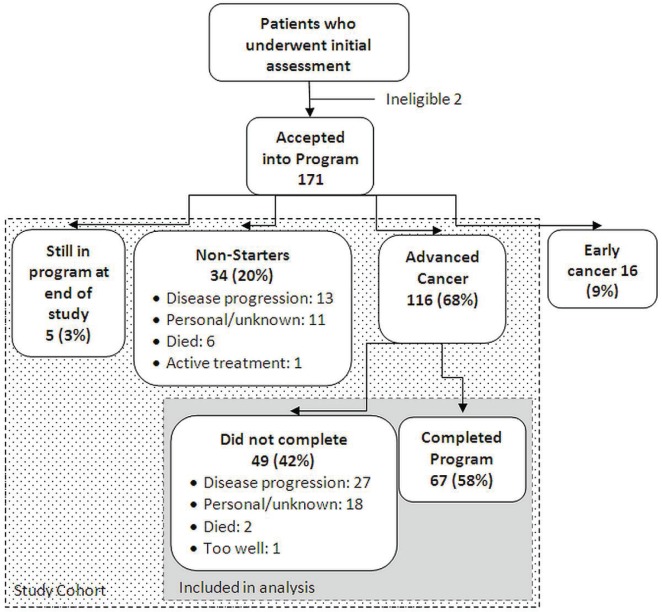

Of 173 patients who underwent the initial assessment, 171 were accepted into the program (Figure 1). Of the 171 patients accepted, 55 were excluded from the analysis: 16 had localized disease, 5 patients were still in the program at the time of the analysis, and 34 patients were accepted into the program but did not start it (“non-starters”). Figure 1 shows the reasons that patients could not start the program. Of the remaining 116 patients, 67 (57.8%) completed the 8-week program, and 49 (42.2%) started the program but did not complete it. Figure 1 lists the reasons that patients did not complete the program. Table i presents baseline characteristics for the patients who did and did not complete the program.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of patients through the Ottawa Palliative Rehabilitation Program.

TABLE I.

Baseline characteristics of patients who did and did not complete the Ottawa Palliative Rehabilitation Program

| Characteristic |

Completed program?

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Patients (n) | 67 | — | 49 | — |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 35 | 52.2 | 27 | 55.1 |

| Women | 32 | 47.8 | 22 | |

| Cancer site (>30 sites) | ||||

| Head and neck | 11 | 16.4 | 6 | |

| Breast | 9 | 13.4 | 8 | |

| Hematologic | 8 | 11.9 | 4 | 8.2 |

| Lung | ||||

| Non-small-cell | 7 | 10.4 | 7 | |

| Small-cell | 2 | 3.0 | 3 | 6.1 |

| Colorectal | 5 | 7.5 | 3 | 6.1 |

| Prostate | 3 | 4.5 | 3 | 6.1 |

| Liver bile duct | 2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Esophageal | 2 | 3.0 | 2 | 4.1 |

| Central nervous system | 2 | 3.0 | 2 | 4.1 |

| Skin | 2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown primary | 2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Urogenital | 1 | 1.5 | 3 | 6.1 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Stage | ||||

| iii | 21 | 31.3 | 15 | |

| iv | 46 | 68.7 | 34 | |

| ecog performance status (ps) | ||||

| 1 | 26 | 38.8 | 17 | |

| 2 | 31 | 46.3 | 23 | |

| 3 | 10 | 14.9 | 9 | |

| Mean age (years) | 61.64±13.0 | 62.37±14.23 | ||

| Medical variables (means) | ||||

| C-Reactive protein | ||||

| Normal | 3.15±2.97 | 3.68±3.23 | ||

| Elevated | 33.46±21.64 | 46.94±37.84 | ||

| White blood cells | 6.80±2.83 | 9.40±9.13 | ||

| ecog ps score | 1.76±0.70 | 1.84±0.72 | ||

| Pulse (bpm) | 78.22±11.98 | 78.34±12.73 | ||

ecog = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

In a comparison of baseline and end data (Table ii) for patients who completed the 8 weeks of the program, significant improvements (with moderate to large effect sizes) were noted across a number of domains. Those domains included ecog ps (p < 0.001, d = 0.90), overall nutritional risk (p = 0.001, d = 0.46), severity of several symptoms [anxiety (p = 0. 004, d = 0.39), depression (p = 0.005, d = 0.37), overall well-being (p = 0.001, d = 0.40), feeling tired (p = 0.001, d = 0.46)], symptom interference in several domains [mood (p < 0.001, d = 0.48), enjoyment (p < 0.001, d = 0.49), general activity (p < 0.001, d = 0.47), work (p = 0.003, d = 0.38)], fatigue [general (p < 0.001, d = 0.61), physical (p < 0.001, d = 0.55), decreased activity (p = 0.001, d = 0.45)], and physiologic functioning [Six Minute Walk Test (p < 0.001, d = 0.80), Timed Up and Go (p < 0.001, d = 0.65), Functional Reach Test (p = 0.001, d = 0.44)].

TABLE II.

Change in functioning from baseline to end of the Ottawa Palliative Rehabilitation Program (paired t-test)

| Effect size and measure | Pts (n) | Baselinea | Completiona | t | p Value | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate-to-large effect | ||||||

| ecog performance status | 56 | 1.8±0.7 | 1.29±0.46 | 6.43 | <0.001 | 0.90 |

| Patient-generated sga | 60 | 8.15±5.29 | 5.98±4.14 | 3.49 | 0.001 | 0.46 |

| esas | ||||||

| Anxiety | 63 | 3.24±2.98 | 2.35±2.48 | 3.01 | 0.004 | 0.39 |

| Depressed | 63 | 2.67±2.63 | 1.89±2.22 | 2.92 | 0.005 | 0.37 |

| Well-being | 64 | 4.85±2.62 | 3.89±2.41 | 3.2b | 0.001 | 0.40 |

| Tired | 63 | 4.89±2.6 | 3.81±2.26 | 3.645 | 0.001 | 0.46 |

| MD Anderson Symptom Index | ||||||

| Mood | 66 | 4.58±3.27 | 3.18±2.55 | 3.83 | <0.001 | 0.48 |

| Enjoyment | 66 | 5.68±3.38 | 4.05±2.89 | 3.99 | <0.001 | 0.49 |

| General activity | 66 | 5.5±3.12 | 3.89±2.7 | 3.8 | <0.001 | 0.47 |

| Work | 66 | 5.59±3.4 | 4.32±3.13 | 3.08 | 0.003 | 0.38 |

| Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory | ||||||

| General | 65 | 15.35±3.3 | 13.35±3.49 | 4.93 | <0.001 | 0.61 |

| Physical | 65 | 15.92±3.27 | 14.09±3.42 | 4.42b | <0.001 | 0.55 |

| Decreased activity | 65 | 15.38±3.62 | 13.69±3.97 | 3.66 | 0.001 | 0.45 |

| Physiologic | ||||||

| Six-Minute Walk Test | 60 | 367.38±123.24 | 422.68±127.6 | −6.17 | <0.001 | 0.80 |

| Timed Up and Go | 60 | 11.39±6.49 | 9.07±3.92 | 5.04* | <0.001 | 0.65 |

| Functional Reach Test | 61 | 32.69±8.03 | 36.01±8 | −3.43 | 0.001 | 0.44 |

| Small-to-moderate effect | ||||||

| esas | ||||||

| Appetite | 63 | 4.06±3.15 | 3.24±2.66 | 2.69 | 0.009 | 0.34 |

| Nausea | 64 | 1.03±1.77 | 0.53±1.33 | 2.41b | 0.016 | 0.30 |

| Drowsy | 63 | 2.71±2.61 | 2.02±2.17 | 2.21 | 0.031 | 0.28 |

| Short of breath | 63 | 2.3±2.76 | 1.92±2.48 | 1.2 | 0.235 | 0.15 |

| Pain | 63 | 3.06±2.26 | 3.06±2.42 | 0 | 1.000 | 0.00 |

| MD Anderson Symptom Index | ||||||

| Relationships | 66 | 3.62±2.94 | 2.86±2.76 | 1.72 | 0.090 | 0.23 |

| Walking | 66 | 4.98±3.24 | 3.92±3.01 | 2.59 | 0.012 | 0.32 |

| Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory | ||||||

| Decreased motivation | 65 | 12.29±4.01 | 10.8±3.77 | 2.83 | 0.006 | 0.35 |

| Mental | 65 | 10.92±4.04 | 10.29±3.79 | 1.11 | 0.272 | 0.14 |

| Physiologic | ||||||

| Berg Balance Scale | 59 | 53.48±5.59 | 54.22±6.3 | −2.64b | 0.008 | 0.34 |

| Grip strength | 55 | 26.68±10.48 | 27.89±10.34 | −1.98b | 0.048 | 0.27 |

All values, mean ± standard deviation.

Normality not assumed. A related-samples Wilcoxon signed rank test used to test significance, and Z/√N used to calculate effect size.

Pts = patients; ecog = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; sga = Subjective Global Assessment; esas = Edmonton Symptom Assessment System.

Improvements with small-to-moderate effect sizes were noted in some symptoms [appetite (p = 0.009, d = 0.34), nausea (p=0.016, d = 0.30), drowsiness (p = 0.031, d = 0.28), shortness of breath (p = 0.235, d = 0.15)], symptom interference in relationships (p = 0.090, d = 0.23) and walking (p = 0.012, d = 0.32), two fatigue-related outcomes [decreased motivation (p = 0.006, d = 0.35) and mental fatigue (p = 0.272, d = 0.14)], and two physiologic outcomes [Berg Balance Scale (p = 0.008, d = 0.34) and grip strength (p = 0.048, d = 0.27)]. Pain did not change (p = 1.000, d = 0.00).

Patients were more likely to finish the program if their crp level was normal than if it was elevated [Wald statistic (1) = 4.78; p = 0.029; relative risk: 1.52; 95% confidence interval: 0.99 to 2.34]. The ecog ps, pulse, and wbc count were not significant predictors of program completion (Table iii). Because of missing biology data, 23 patients (8 completers, 15 non-completers) were excluded from the regression.

TABLE III.

Significant medical predictors of program completion, by logistic regression

| Variable | Wald statistic | df | p Value | Relative risk |

95% cl

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Significant | ||||||

| C-Reactive protein | 4.78 | 1 | 0.029 | 1.52 | 0.99 | 2.34 |

| Nonsignificant | ||||||

| ecog performance status | 0.26 | 1 | 0.614 | |||

| White blood cells | 1.94 | 1 | 0.164 | |||

| Pulse | 0.29 | 1 | 0.593 | |||

cl = confidence limits; ecog = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

4. DISCUSSION

Patients in our study who had advanced cancer and who completed the multimodal interprofessional prp demonstrated a wide range of improvements. Moderate-to-large effects (defined by an effect size of 0.5 or greater) were observed in ecog ps, endurance, mobility, general fatigue, and physical fatigue. Small-to-moderate improvements (defined by an effect size between 0.2 and 0.5) were observed in nutrition status; symptom interference in mood, enjoyment, general activity, and work; decreased activity; balance and function; and several symptoms. Some measures that did not meet statistical significance—such as severity of drowsiness and appetite symptoms, interference in relationships and walking, decreased motivation, Berg Balance Scale, and grip strength—still demonstrated moderate improvement. Nonsignificant results with small effect size (d < 0.2) were observed for the severity of two symptoms (shortness of breath and pain) and for mental fatigue. It is important to note that patients did not experience worsening symptoms in any of the domains. Overall, our findings suggest that patients with life-limiting cancers who have undergone an interprofessional patient-centered prp experienced improvements in many domains.

The improvements found in the current study are important because they contrast with the usual pattern seen in patients living with advanced cancer and other chronic illnesses35. Typically, such patients have a steady burden of symptoms until the final weeks before death, at which point symptoms drastically worsen. In contrast, the results of the current research demonstrate that patients can experience many improvements. Given the contrast with the existing literature, we posit that palliative rehabilitation is a beneficial application of early palliative care. Early palliative care has been cited as a necessary next step in the advancement of care for patients living with cancer, possibly even in conjunction with active treatment36.

In addition to direct interdisciplinary intervention, the prp strives to foster additional sources of healing, such as social support. Social support has been found to help patients adjust to illness, to increase adherence to treatment, and to have beneficial effects on well-being, stress, and immunity37–39. During the prp, patients are encouraged to bring their caregivers to the gym sessions. The patients also bond and form friendships with their peers during the exercise sessions, and they receive support from the prp team. All of the those contacts might improve motivation by providing friendship, solidarity, and a sense of belonging and might help patients bypass the initial barriers of undertaking an exercise program (for example, lacking motivation, feeling deconditioned, or having difficulty incorporating a regular exercise routine)40.

Normal serum crp was found to be a significant biologic predictor of program completion. That finding was expected, because elevated crp (alone or coupled with an elevated wbc count) has been identified as an ominous indicator of shortened survival41. In the present study, patients with normal levels of crp were 1.52 times more likely to complete the program than were patients with elevated levels of crp. Inflammation, as indicated by elevated crp, promotes incapacity and suffering; compared with patients having a normal crp, those with an elevated reading are likely to experience more rapid tumour progression42. Although the exercise and psychosocial components of our rehabilitation program might contribute to the reduction of crp levels43–45, patients with high serum crp might find it more difficult to complete the program because they are usually more ill.

Clinically, patients reported that they were 70%–100% satisfied with the program46. Complaints involved issues such as parking and a desire for follow-up sessions (although patients are referred to community resources for follow-up on prp completion). Patients did not complain about the length of the 3-hour interviews or the program structure in general. Given the current findings, we suggest several changes to the program, in a multipronged approach that might improve a chronic inflammatory state. Those changes might potentially increase the completion rate and perhaps generalize to functioning in overall life for the patients. From a nutrition perspective, the additional interventions could include an “antiinflammatory diet” with increased emphasis on branched-chain amino acids47, vitamin D supplementation as a regular feature48, and omega-3 fatty acid supplements49. From an exercise perspective, the changes would include modifications to our current balance of aerobic and resistance recommendations4,9,50. Consideration is also being given to making pharmaceutical adjustments to the program, including considering a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug for patients with high serum crp otherwise judged to be at low risk for adverse reactions to such drugs. Although support in the literature for the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs is generally positive, more research is necessary to support the efficacy of that approach51.

The major limitation of the current study is the limited availability of potential methodologic designs for this patient group. Although the results appear promising compared with those in the existing literature35, we cannot say with certainty that our program caused the observed improvements. The next logical step would be to create control or contrast groups, but some patients have only a few months to live. In those patients, withholding or replacing treatment for several months creates ethical issues. We are therefore precluded from using the usual methods—for example, wait-list controls or randomized controlled trials—to determine the unique effect of the prp. Another limitation is the lack of interim measurements. Almost 37% of the identified sample did not provide a specific reason for withdrawal. Given that the esas data were not obtained weekly in all patients, and that the ecog ps was not assessed each week, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the experiences of the patients throughout their 8 weeks in the program. Those circumstances also preclude us from contrasting the progression of symptom severity, disease status, or disease progression in patients who did and did not complete the program. Finally, patients received individual interventions specific to their individual needs and goals—that is, the interventions were not uniform. The differences might have inflated patient improvements by focusing on areas with the worst functioning, thereby allowing for the largest possible gains to be experienced. Statistically, that approach may present a potential artifact, but clinically, it is a strength. In addition it increases external validity: individualized programs are the norm in clinical practice, and such programs are likely to be patient-centered rather than uniform.

Future research directions include examining mechanisms of change that might influence patient improvements. An analysis of that kind would be useful to better understand which elements of this complex program are the most beneficial. A pre–post examination of patient use of various health care services could also suggest whether patients are experiencing an improved level of functioning overall after having undergone such a program. The impact of the program in keeping patients functional for longer periods in the home setting warrants its continuation. Identifying the minimal program duration that can result in positive and sustained results will also be important; it is possible that benefits may be realized sooner than the full 8 weeks, which would have important resource implications. Social support is another important area to examine, given its support in the current literature as an important factor in both quality of life and prognosis. Finally, longitudinal follow-up to examine whether gains are maintained would better inform the evaluation of the benefits that patients are able to experience.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The prp offers an interprofessional holistic approach that positions the patient at the centre of an individualized program. Each discipline offers its own expertise, but collaboration and discussion between the professionals is vital so that all the interventions complement one another. The outcomes of this program appear to be reduced symptom burden; reduced interference by symptoms in daily life; and improved nutrition, physical and functional status, and overall well-being. It is expected that, through continued application of the skills acquired from the prp, patients will demonstrate reasonable maintenance of their gains, a decreased reliance on the health care system, and fewer emergency room visits. The latter hypotheses have to be tested in future studies. By affording the opportunity for rehabilitation to palliative care patients who can manage the intensity required by such a program, “living” with cancer can be a reality for many.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the prp team: Ravi Bhargava, Lisa Larose–Savage, Kitty Martinho, Carolyn Richardson, Julie Martin–MacKay, Cecilia Cranston, Anne-Marie Burns, and Jennifer MacIntosh for clinical contributions, and Danielle Sinden for administrative support. We are grateful to Dwayne Schindler for statistical support.

This manuscript was presented at the following conferences in 2012: Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology, Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, International Congress on Palliative Care, and Union for International Cancer Control.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

This work was supported by the Ottawa Regional Cancer Foundation, Bruyère Continuing Care, The Bruyere Research Institute, and the Bruyère Foundation. The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Chasen MR, Dippenaar AP. Cancer nutrition and rehabilitation—its time has come! Curr Oncol. 2008;15:117–22. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i3.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kjaer TK, Johansen C, Ibfelt E, et al. Impact of symptom burden on health related quality of life of cancer survivors in a Danish cancer rehabilitation program: a longitudinal study. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:223–32. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.530689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chasen M, Bhargava R. Gastrointestinal symptoms, electrogastrography, inflammatory markers, and pg-sga in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;20:1283–90. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spence RR, Heesch KC, Brown WJ. Exercise and cancer rehabilitation: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isenring EA, Capra S, Bauer JD. Nutrition intervention is beneficial in oncology outpatients receiving radiotherapy to the gastrointestinal or head and neck area. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:447–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isenring EA, Bauer JD, Capra S. Nutrition support using the American Dietetic Association medical nutrition therapy protocol for radiation oncology patients improves dietary intake compared with standard practice. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:404–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.León–Pizarro C, Gich I, Barthe E, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of training in relaxation and guided imagery techniques in improving psychological and quality-of-life indices for gynecologic and breast brachytherapy patients. Psychooncology. 2007;16:971–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korstjens I, Mesters I, van der Peet E, Gijsen B, van den Borne B. Quality of life of cancer survivors after physical and psychosocial rehabilitation. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2006;15:541–7. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000220625.77857.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knols R, Aaronson NK, Uebelhart D, Fransen J, Aufdemkampe G. Physical exercise in cancer patients during and after medical treatment: a systematic review of randomized and controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3830–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamura H. Importance of rehabilitation in cancer treatment and palliative medicine. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:733–8. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eades M, Murphy J, Carney S, et al. Effect of an interdisciplinary rehabilitation program on quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer: review of clinical experience. Head Neck. 2013;35:343–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.22972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartlett L, Sloots K, Nowak M, Ho YH. Biofeedback therapy for symptoms of bowel dysfunction following surgery for colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:319–26. doi: 10.1007/s10151-011-0713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorsen L, Courneya K, Stevinson C, Fosså SD. A systematic review of physical activity in prostate cancer survivors: outcomes, prevalence, and determinants. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:987–97. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, Klassen TP, Mackey JR, Courneya KS. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2006;175:34–41. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segal R, Evans W, Johnson D, et al. Structured exercise improves physical functioning in women with stages i and ii breast cancer: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:657–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirshblum S, O’Dell MW, Ho C, Barr K. Rehabilitation of persons with central nervous system tumors. Cancer. 2001;92(suppl):1029–38. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4+<1029::AID-CNCR1416>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemoignan J, Chasen M, Bhargava R. A retrospective study of the role of an occupational therapist in the cancer nutrition rehabilitation program. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1589–96. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0782-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conn V, Hafdahl A, Porock D, McDaniel R, Nielsen PJ. A meta-analysis of exercise interventions among people treated for cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:699–712. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0905-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eades M, Chasen M, Bhargava R. Rehabilitation: long-term physical and functional changes following treatment. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25:222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Townsend D, Accurso–Massana C, Lechman C, Duder S, Chasen M. Cancer nutrition rehabilitation program: the role of social work. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:12–17. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundholm K, Daneryd P, Bosæus I, Körner U, Lindholm E. Palliative nutritional intervention in addition to cyclooxygenase and erythropoietin treatment for patients with malignant disease: effects on survival, metabolism, and function. Cancer. 2004;100:1967–77. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization (who) WHO Definition of Palliative Care [Web page] Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. [Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/; cited April 16, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chasen M, Bhargava R. A descriptive review of the factors contributing to nutritional compromise in patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1345–51. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0684-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000;88:2164–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2164::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89:1634–46. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::AID-CNCR29>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leuenberger M, Kurmann S, Stanga Z. Nutritional screening tools in daily clinical practice: the focus on cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(suppl m2):S17–27. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0805-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ottery FD. Definition of standardized nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition. 1996;12(suppl):S15–19. doi: 10.1016/0899-9007(96)90011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smets EMA, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (mfi) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315–25. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steffen TM, Hacker TA, Mollinger L. Age- and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: Six-Minute Walk Test, Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up and Go Test, and gait speeds. Phys Ther. 2002;82:128–37. doi: 10.1093/ptj/82.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simmonds MJ. Physical function in patients with cancer: psychometric characteristics and clinical usefulness of a physical performance test battery. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:404–14. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00502-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up and Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norman K, Stobäus N, Smoliner C, et al. Determinants of hand grip strength, knee extension strength and functional status in cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:586–91. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–55. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynn J, Adamson DM. Living Well at the End of Life Adapting Health Care to Serious Chronic Illness in Old Age. Washington, DC: RAND Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruera E, Yennurajalingam S. Palliative care in advanced cancer patients: how and when? Oncologist. 2012;17:267–73. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23:207–18. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ell K. Social networks, social support, and health status: a review. Soc Serv Rev. 1984;58:133–49. doi: 10.1086/644168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29:377–87. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaney J, Lowe–Strong A, Rankin J, Campbell A, Allen J, Gracey J. The cancer rehabilitation journey: barriers to and facilitators of exercise among patients with cancer-related fatigue. Phys Ther. 2010;90:1135–47. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kasymjanova G, MacDonald N, Agulnik JS, et al. The predictive value of pre-treatment inflammatory markers in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:52–8. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i4.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fearon KC, Voss AC, Hustead DS, on behalf of the Cancer Cachexia Study Group Definition of cancer cachexia: effect of weight loss, reduced food intake, and systemic inflammation on functional status and prognosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1345–50. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ford ES. Does exercise reduce inflammation? Physical activity and C-reactive protein among U.S. adults. Epidemiology. 2002;13:561–8. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fang CY, Reibel DK, Longacre ML, Rosenzweig S, Campbell DE, Douglas SD. Enhanced psychosocial well-being following participation in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program is associated with increased natural killer cell activity. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:531–8. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of exercise training in subjects with type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome is dependent on exercise modalities and independent of weight loss. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20:608–17. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savage–Larose L, Gravelle D, Chasen M, Bhargava R. Patient satisfaction with an 8 week palliative rehabilitation program [abstract 385]. MASCC/ISOO 2012 International Symposium on Supportive Care in Cancer. Proceedings of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer; New York, NY. June 28–29, 2012; Geneva, Switzerland: Kenes International; 2012. p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laviano A, Muscaritoli M, Cascino A, et al. Branched-chain amino acids: the best compromise to achieve anabolism? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8:408–14. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000172581.79266.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stone CA, Kenny RA, Healy M, Walsh JB, Lawlor PG. Vitamin D depletion: of clinical significance in advanced cancer? Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:865–7. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Mazurak VC. n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids: the potential role for supplementation in cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15:246–51. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328351c32f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galvao DA, Newton RU. Review of exercise intervention studies in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:899–909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reid J, Hughes CM, Murray LJ, Parsons C, Cantwell MM. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of cancer cachexia: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013;27:295–303. doi: 10.1177/0269216312441382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]