Abstract

Background

The survival benefit for single-agent anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr) therapy compared with combination therapy with irinotecan in KRAS wildtype (wt) metastatic colorectal cancer (mcrc) patients in the third-line treatment setting is not known. The objective of the present study was to describe the characteristics of, and to compare survival outcomes in, two cohorts of patients treated with either singleagent panitumumab or combination therapy with cetuximab and irinotecan.

Methods

The study enrolled patients with KRAS wt mcrc previously treated with both irinotecan and oxaliplatin who had received either panitumumab or combination cetuximab–irinotecan before April 1, 2011, at the BC Cancer Agency (bcca). Patients were excluded if they had received anti-egfr agents in earlier lines of therapy. Data were prospectively collected, except for performance status (ps), which was determined by chart review. Information about systemic therapy was extracted from the bcca Pharmacy Database.

Results

Of 178 eligible patients, 141 received panitumumab, and 37 received cetuximab–irinotecan. Compared with patients treated with cetuximab–irinotecan, panitumumab-treated patients were significantly older and more likely to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ecog) ps of 2 or 3 (27.7% vs. 2.7%, p = 0.001). Other baseline prognostic variables and prior and subsequent therapies were similar. Median overall survival was 7.7 months for the panitumumab group and 8.3 months for the cetuximab–irinotecan group. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that survival outcomes were similar regardless of the therapy selected (hazard ratio: 1.28; p = 0.34). An ecog ps of 2 or 3 compared with 0 or 1 was the only significant prognostic factor in this treatment setting (hazard ratio: 3.37; p < 0.01).

Conclusions

Single-agent panitumumab and cetuximab–irinotecan are both reasonable third-line treatment options, with similar outcomes, for patients with chemoresistant mcrc.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, multivariate analysis, anti-egfr, survival, panitumumab, irinotecan, cetuximab, mcrc

1. INTRODUCTION

Survival for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mcrc) has improved substantially as a result of advances in surgical resection and systemic therapy 1–3. Two such therapies are the monoclonal antibodies, panitumumab and cetuximab, which are directed against the human epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr). In randomized phase iii studies, these antibodies have demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of KRAS wild-type (wt) mcrc in combination with first-line chemotherapy 4–9 and second-line chemotherapy 10–12, and as single agents in the third-line setting 13–15.

The clinical use of anti-egfr therapy varies, being influenced by national treatment and reimbursement guidelines, the resectability of hepatic metastases, and the patient’s toleration of other systemic agents. Anti-egfr therapies are particularly favoured for third-line treatment, as shown by a large U.S. study of 1665 mcrc patients treated between 2004 and 2008, which demonstrated that the most common third-line treatment regimens contained anti-egfr agents. Of the patients enrolled in that study, 278 (16.7%) received combination therapy with both cetuximab and irinotecan, and 142 (8.5%) received either single-agent panitumumab or cetuximab 16.

An early randomized phase ii study of patients with unselected irinotecan-resistant KRAS wt mcrc demonstrated that, compared with patients receiving cetuximab alone, those treated with cetuximab–irinotecan combination therapy experienced significantly higher response rates, longer progression-free survival, and increased treatment toxicity 13. However, the superiority of combination therapy compared with single-agent therapy in terms of overall survival is not established. Studies have shown a survival benefit for single-agent therapies (for example, cetuximab and panitumumab) compared with best supportive care 14,15. Compared with best supportive care, single-agent therapy with cetuximab conferred a survival benefit, but a randomized trial of panitumumab compared with best supportive care was obscured by a high level of crossover to the treatment arm. However, no other studies have compared overall survival between single anti-egfr agents and combination cetuximab–irinotecan treatment in the third-line setting.

In the absence of sufficient evidence, decisions about whether to administer a single agent or combination therapy with an anti-egfr agent in the third-line setting are currently guided by clinical factors and physician and patient choice. Understanding the benefits of single-agent compared with combination therapy would help to support clinical decision-making. The objective of the current study was therefore to describe the characteristics of, and to compare survival outcomes in, British Columbia patients treated with either single-agent panitumumab or combination therapy with cetuximab–irinotecan.

In British Columbia, anti-egfr therapy is restricted to the third-line setting for patients with KRAS wt mcrc previously treated with irinotecan, oxaliplatin, and 5-fluorouracil. Physicians and their patients are given the choice of either single-agent panitumumab or combination therapy with cetuximab–irinotecan; there is no access to cetuximab monotherapy in the provincial funding model. Crossover or sequential therapy with both panitumumab and cetuximab is not permitted. Results from the present study may influence clinical decisions about the choice of single-agent anti-egfr therapy or combination therapy in the third-line setting.

2. METHODS

2.1. Selection and Description of Participants

Our study enrolled patients with a diagnosis of mcrc who had been referred to the BC Cancer Agency (bcca), a provincial cancer agency with 5 clinics throughout the province, serving a population of 4.4 million. The bcca is the sole funding body for systemic cancer therapy in the province, and 65% of all systemic therapy is administered at bcca or bcca-affiliated clinics.

Single-agent panitumumab and combination cetuximab–irinotecan were provincially funded as of July 1, 2009, for KRAS wt patients with mcrc previously treated with both irinotecan and oxaliplatin. Patients eligible for our study were identified in the bcca Pharmacy Database as having received at least 1 cycle of either panitumumab or cetuximab– irinotecan before April 1, 2011 (date chosen to allow for a minimum of 4 months of follow-up for all included patients). Eligibility for anti-egfr therapy required documentation of previous treatment with, or ineligibility for, oxaliplatin and irinotecan. Documentation of KRAS wt status was required and verified as a condition of therapy. Patients were excluded if they had received panitumumab or cetuximab in earlier lines of therapy. Only 1 patient was excluded from the study for that reason, having previously received panitumumab therapy with oxaliplatin, leaving 178 patients eligible for the study.

2.2. Data Extraction

In a retrospective chart review, each patient’s ecog performance status (ps) at the date of the first treatment cycle with panitumumab or cetuximab–irinotecan was abstracted. When the ecog status was not present, it was coded as “unknown” rather than being inferred. Other patient, tumour, and treatment characteristics were prospectively collected in the GI Cancers Outcomes Unit database. The GI Cancers Outcomes Unit was established at the bcca in 2004; it prospectively documents tumour, patient, and treatment characteristics for all patients referred to the bcca provincial clinics. Information about local, regional, and distant relapse is collected on an ongoing basis through letters to referring physicians. Mortality information is obtained through the Provincial Cancer Registry.

Information about systemic therapy—including the protocol on which the patient initiated therapy and the number of cycles (including range and median) of all therapies (panitumumab, cetuximab–irinotecan, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and bevacizumab)—was obtained from the bcca Pharmacy Database. Data about any systemic therapies after panitumumab or cetuximab–irinotecan were also obtained.

2.3. Statistical Methods

Overall survival was calculated from the date of the first treatment cycle with anti-egfr therapy to the date of death (from any cause) or date of last contact, if the patient was still alive. The Kaplan–Meier approach was used to estimate overall survival, and differences between groups were assessed using a log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to investigate independent associations between outcome and the various prognostic variables. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from the model for all prognostic variables.

Chemotherapy data from the bcca Pharmacy Database was categorized by type and by timing in relation to panitumumab and cetuximab–irinotecan therapy. Descriptive statistics were calculated using SPSS (version 14.0: SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.), with differences between groups evaluated using the chisquare test for categorical variables and the t-test or Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables.

The study was approved by the University of British Columbia and bcca Research Ethics Board and the BC Cancer Registry.

3. RESULTS

The 178 eligible patients with documented KRAS wt mcrc who commenced therapy with either panitumumab or cetuximab–irinotecan had a median follow-up (in living patients) of 9.2 months for the panitumumab group and 10.8 months for the cetuximab–irinotecan group.

Table i summarizes baseline patient characteristics. By a factor of nearly 4, patients were more likely to have received panitumumab (n = 141) than cetuximab–irinotecan (n = 37). Compared with patients who received cetuximab–irinotecan, those who received panitumumab were significantly older (median age: 66 years vs. 60 years; p = 0.05). Panitumumab-treated patients were also more likely to have a worse ecog ps: an ecog ps of 2 or 3 was documented for 27.7% of the panitumumab group compared with only 2.7% of the cetuximab–irinotecan group. Other baseline prognostic variables, such as frequency of metastasectomy, stage at initial diagnosis, receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, and resection of the primary tumour were similar in the patient groups.

TABLE I.

Baseline characteristics of 178 study participants at the time of initiation of therapy with either panitumumab (Pmab) or cetuximab–irinotecan (Cmab–Irino)

| Characteristic | Pmab | Cmab–Irino | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 141 | 37 | |

| Age at cycle 1 of egfr therapy | |||

| Median | 66 | 60 | 0.05 |

| Range | 34–86 | 44–88 | |

| Sex [n (%)] | |||

| Men | 83 (58.9) | 24 (64.9) | 0.57 |

| Women | 58 (41.1) | 13 (35.1) | |

| Stage at initial mcrc diagnosis [n (%)] | |||

| i/ii | 20 (14.2) | 5 (13.5) | 0.59a |

| iii | 49 (34.8) | 10 (27.0) | |

| iv | 70 (49.6) | 22 (59.5) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Resection of primary tumour [n (%)] | |||

| Yes | 125 (88.7) | 30 (81.1) | 0.27 |

| No | 16 (11.3) | 7 (18.9) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, stages i–iii [n (%)] | |||

| Yes | 53 (76.8) | 12 (80.0) | 0.79b |

| No | 16 (23.2) | 3 (20.0) | |

| ecog performance status [n (%)] | |||

| 0/1 | 57 (40.4) | 23 (62.2) | |

| 2 | 32 (22.7) | 1 (2.7) | |

| 3 | 7 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 45 (31.9) | 13 (35.1) | |

| Resection of liver or lung metastases [n (%)] | |||

| Yes | 15 (10.6) | 5 (13.5) | 0.57 |

| No | 126 (89.4) | 32 (86.5) | |

| Prior systemic therapy | |||

| With oxaliplatin [n (%)] | 133 (94) | 35 (95) | |

| Cycles (n) | |||

| Median | 9.0 | 9.0 | 0.65 |

| Mean | 9.1 | 9.8 | |

| Range | 1–26 | 3–24 | |

| With irinotecan [n ()] | 139 (99) | 36 (97) | |

| Cycles (n) | |||

| Median | 12.0 | 13.5 | 0.06 |

| Mean | 13.2 | 16.8 | |

| Range | 1–38 | 3–49 | |

| With bevacizumab [n (%)] | 99 (70) | 28 (76) | |

| Cycles (n) | |||

| Median | 12.0 | 12.5 | 0.14 |

| Mean | 13.3 | 15.6 | |

| Range | 1–38 | 4–38 |

Determined using patients with known values only.

At least 1 cell had less than expected count; p value may therefore not be reliable.

egfr = epidermal growth factor receptor; mcrc = metastatic colorectal cancer; ecog = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Table i also shows the type and duration of systemic therapy received by patients before anti-egfr therapy. Most patients had already received irinotecan and oxaliplatin, a requirement for provincial funding of anti-egfr therapy. The duration of prior irinotecan therapy was longer among patients receiving cetuximab–irinotecan (p = 0.06). A high proportion of patients in both groups received prior bevacizumab.

For every-2-weeks panitumumab, the median and mean number of cycles were both 9.0. For every-2-weeks combination cetuximab–irinotecan, the median and mean number of cycles were 8.0 and 9.8 respectively. For cetuximab, the median and mean number of cycles were 10 and 13.2, regardless of whether that agent given in combination with irinotecan. The latter finding indicates that the irinotecan portion of the initial combination therapy may have been discontinued and that patients were then treated with continued single-agent cetuximab.

As Table ii shows, subsequent systemic therapy of any kind was given to 30 panitumumab patients (21.3%), including the 13 patients (9.2%) who received irinotecan. Of the cetuximab–irinotecan patients, 9 (24.3%) received subsequent therapy including a single patient (2.7%) who received irinotecan. Other systemic therapies administered included oxaliplatin and experimental treatments that were part of phase i–iii clinical trials at the bcca.

TABLE II.

Systemic therapy received by study participants after panitumumab (Pmab) or cetuximab–irinotecan (Cmab–Irino)

| Systemic therapy | Pmab [n (%)] | Cmab–Irino [n (%)] | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any | 30 (21.3) | 9 (24.3) | 0.69 |

| Oxaliplatin | 10 (7.1) | 4 (10.8) | 0.46 |

| Irinotecan | 13 (9.2) | 1 (2.7) | 0.19 |

| Other | 26 (18.4) | 8 (21.6) | 0.66 |

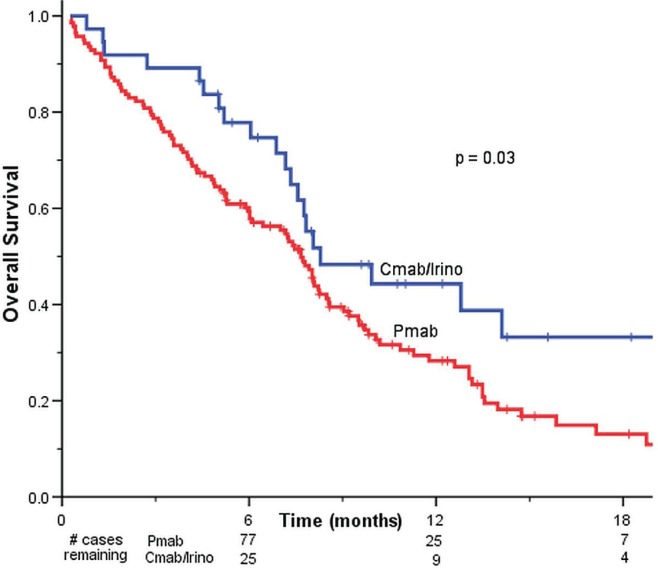

Kaplan–Meier overall survival analysis (Figure 1) showed a modest but statistically significant increase in overall survival for patients treated with cetuximab–irinotecan than for those treated with panitumumab (8.3 months vs. 7.7 months, p = 0.03).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival in all study participants treated with panitumumab (Pmab, n = 141) or cetuximab–irinotecan (Cmab–Irino, n = 37).

A multivariate analysis estimated the prognostic impact of patient and treatment variables, including single-agent versus combination anti-egfr therapy (Table iii). Survival outcomes were not statistically significantly different in patients treated with cetuximab–irinotecan (referent) and panitumumab (hazard ratio: 1.28; p = 0.34). Only ps was independently prognostic: survival was inferior for patients having an ecog ps of 2 or 3 compared with those having an ecog ps of 0 or 1 (hazard ratio: 3.37; p < 0.01). Patients whose ecog ps was unknown had a survival outcome similar to that in patients with an ecog ps of 0 or 1. On multivariate analysis, there was no survival difference between patients treated with panitumumab and those treated with cetuximab–irinotecan, and no significant associations were observed between survival and any of the other prognostic variables, including age, resection status, history of metastasectomy, or stage at diagnosis.

TABLE III.

Multivariable analysis of overall survival, by patient and treatment variable

| Variable | Pts (n) | p Value | hr | 95% ci |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-egfr treatment | ||||

| Cetuximab–irinotecan | 37 | Reference | ||

| Panitumumab | 141 | 0.34 | 1.28 | 0.77 to 2.14 |

| Age at cycle 1 of anti-egfr | ||||

| <65 | 88 | Reference | ||

| ≥65 | 90 | 0.51 | 1.14 | 0.78 to 1.67 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 71 | Reference | ||

| Male | 107 | 0.67 | 1.08 | 0.75 to 1.57 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, stages i–iii | ||||

| No | 19 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 65 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.24 to 1.52 |

| Resection of primary tumour | ||||

| No | 23 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 155 | 0.18 | 0.67 | 0.38, 1.20 |

| Prior bevacizumab | ||||

| No | 51 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 127 | 0.26 | 1.27 | 0.84 to 1.90 |

| Resection of liver or lung metastases | ||||

| No | 158 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 20 | 0.50 | 0.81 | 0.44 to 1.49 |

| ecog performance status | ||||

| 0/1 | 80 | Reference | ||

| 2/3 | 40 | <0.01 | 3.37 | 2.08 to 5.45 |

| Unknown | 58 | 0.12 | 1.41 | 0.92 to 2.17 |

| Stage at initial mcrc diagnosis | ||||

| i/ii | 25 | Reference | ||

| iii | 59 | 0.49 | 1.35 | 0.57 to 3.16 |

| iv | 92 | 0.39 | 0.77 | 0.42 to 1.41 |

egfr = epidermal growth factor receptor; ecog = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; mcrc = metastatic colorectal cancer.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study of 178 provincially treated patients, the duration of survival was similar for KRAS wt mcrc patients treated with single-agent panitumumab and those treated with combination cetuximab–irinotecan. Patients treated with single-agent anti-egfr therapy were older and more likely to have an ecog ps of 2 or 3 at the time of therapy initiation. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that survival outcomes were similar regardless of the therapy selected; an ecog ps 2 of 3 was the only significant prognostic factor in this treatment setting.

Our study is strengthened by a relatively balanced distribution of prognostic characteristics between the two treatment arms, with the exception of ecog ps. That balance is likely a result of the identical provincially-specified eligibility requirements for both panitumumab and cetuximab–irinotecan therapy. The duration and type of previous systemic therapy, previous administration of bevacizumab or adjuvant therapy, stage at initial diagnosis, and previous metastasectomy were balanced between the two groups.

Study outcomes were similar to those seen in previous phase iii trials that examined outcomes of anti-egfr therapies compared with best supportive care 14,15. The median and mean number of cycles of panitumumab in our group were 9 and 9 respectively, compared with 8 and 10 in the phase iii study of panitumumab compared with best supportive care 15. Overall survival for patients with an ecog ps of 0, 1, or unknown, treated with single-agent panitumumab, was 8.5 months; it was 9.5 months in patients treated with single-agent cetuximab in the co.17 trial 14. But because more than one anti-egfr monoclonal antibody was used in the single-agent group, the latter study is not a pure comparison of the two treatment strategies. A relevant clinical question is whether there are differences in the efficacy of the two anti-egfr monoclonal antibodies, panitumumab and cetuximab. That comparison is the subject of the recently reported head-to-head aspecct study, in which patients with advanced KRAS wt mcrc were randomized to standard-dose panitumumab or cetuximab. Results from that study do not point to a significant difference in efficacy between the two agents, as evidenced by the lack of a difference in survival duration on multivariate analysis17.

The biweekly cetuximab–irinotecan regimen used during our study differs from that used in the initial randomized phase ii study 13 and from the dosing given in the product monograph, which specifies an initial loading dose followed by weekly administration of cetuximab. The current bcca treatment protocol was adopted after published data demonstrated similar progression-free and overall survival with weekly compared with biweekly cetuximab in combination with biweekly irinotecan 18–20. The biweekly regimen was chosen for its greater efficiency and convenience compared with the weekly regimen. The 50% reduction in the frequency of treatment lowers the utilization of pharmacy and chemotherapy nurse and chair resources; it is more convenient for patients; and it reduces the use of antihistamines and corticosteroids, which are routinely administered before cetuximab infusion 21.

The lack of a clinically meaningful difference in overall survival between the two treatment arms evaluated here calls into question the benefit for irinotecan in this treatment setting. The addition of irinotecan to cetuximab doubled the response rate in a previous randomized clinical trial 13, but the irinotecan might not be required to achieve the survival gains associated with cetuximab in the third-line setting. The randomized clinical trial of cetuximab compared with best supportive care resulted in a significant improvement in overall survival to 9.5 months from 4.8 months (p < 0.001) 14. Given the results of the present study, it is questionable whether combination therapy with cetuximab–irinotecan significantly improves on that survival gain. Patients eligible for further chemotherapy might be offered irinotecan sequentially after cetuximab or panitumumab. In the present study, 21% of patients treated with single-agent panitumumab were treated with subsequent systemic therapy, including 9% who received irinotecan. Of the patients treated with panitumumab or cetuximab–irinotecan, similar proportions were treated with subsequent systemic therapy, which indicates that the administration of cytotoxic therapy in the third-line setting with anti-egfr agents is not associated with a higher likelihood of receiving subsequent systemic therapy.

Any retrospective review is subject to numerous limitations, including lack of standardized data on quality of life, toxicity, and response rate. The ecog ps data were retrospectively obtained from chart review, and the field was coded “unknown” when not recorded by the treating physicians. An additional challenge to the study results is that the sample was relatively small, particularly for the cetuximab–irinotecan cohort, making the analysis somewhat underpowered.

Choice of therapy is influenced by both physician and patient variables. Physician variables include familiarity with the treatment regimen and perceived importance of response rate, which is higher with combination than with single-agent therapy. Because of past experiences treating patients with cetuximab alone during a large Canadian-led clinical trial 14, treating physicians might have been more comfortable with single-agent anti-egfr therapy than with combination therapy containing cetuximab. Patient factors include age, ps, and response to and tolerance of prior irinotecan. Despite documented differences in response rates between single-agent cetuximab (10.8%) and combination cetuximab–irinotecan (22.8%) 13, response rates may be less clinically relevant in this advanced treatment setting, particularly in the absence of symptoms related to bulky disease.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Factors that influence decision-making in the third-line setting of mcrc include treatment convenience and toxicity, patient quality of life, and response rate. Results of the present study support the notion that either single-agent panitumumab or combined cetuximab–irinotecan are reasonable third-line treatment options, with similar outcomes, for patients with chemotherapy-resistant mcrc.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research support for this study was provided by the bcca. Some of this work was presented in abstract form at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting in February 2012.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

None of the authors received funding support for the preparation or publication of this work. No author has a financial conflict of interest.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Grothey A, Sugrue MM, Purdie DM, et al. Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a large observational cohort study (brite) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5326–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renouf DJ, Lim HJ, Speers C, et al. Survival for metastatic colorectal cancer in the bevacizumab era: a population-based analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, et al. Randomized, phase iii trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (folfox4) versus folfox4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the prime study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4697–705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Láng I, et al. Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2011–19. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:663–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maughan TS, Adams RA, Smith CG, et al. Addition of cetuximab to oxaliplatin-based first-line combination chemotherapy for treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: results of the randomised phase 3 mrc coin trial. Lancet. 2011;377:2103–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60613-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tveit K, Guren T, Glimelius B, et al. Randomized phase iii study of 5-fluorouracil/folinate/oxaliplatin given continuously or intermittently with or without cetuximab, as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: The nordic vii study ( NCT00145314), by the Nordic Colorectal Cancer Biomodulation Group [abstract 365] J Clin Oncol. 2011;29 [Available online at: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/70979-103; cited October 19, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peeters M, Price TJ, Cervantes A, et al. Randomized phase iii study of panitumumab with fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (folfiri) compared with folfiri alone as second-line treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4706–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.6055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sobrero AF, Maurel J, Fehrenbacher L, et al. epic: phase iii trial of cetuximab plus irinotecan after fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2311–19. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seymour MT, Brown SR, Middleton G, et al. Panitumumab and irinotecan versus irinotecan alone for patients with KRAS wild-type, fluorouracil-resistant advanced colorectal cancer (piccolo): a prospectively stratified randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:749–59. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karapetis CS, Khambata–Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amado RG, Wolf M, Peeters M, et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1626–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.7116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess GP, Wang PF, Quach D, Barber B, Zhao Z. Systemic therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: patterns of chemotherapy and biologic therapy use in U.S. medical oncology practice. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:301–7. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price TJ, Peeters M, Kim TW, et al. aspecct: a randomized, multicenter, open-label, phase 3 study of panitumumab (pmab) vs cetuximab (cmab) for previously treated wild-type (wt) KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer (mcrc). Proceedings of the European Cancer Congress 2013; Amsterdam, Netherlands. September 27–October 1, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roca J, Alonso V, Pericay C, et al. Cetuximab given every 2 weeks (q2w) plus irinotecan, as feasible option, for previously treated patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mcrc) [abstract 15122] J Clin Oncol. 2008;26 [Available online at: http://meeting.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/26/15_suppl/15122; cited October 28, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeiffer P, Nielsen D, Bjerregaard J, Qvortrup C, Yilmaz M, Jensen B. Biweekly cetuximab and irinotecan as third-line therapy in patients with advanced colorectal cancer after failure to irinotecan, oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1141–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin–Martorell P, Rosello S, Rodriguez–Braun E, Chirivella I, Bosch A, Cervantes A. Biweekly cetuximab and irinotecan in advanced colorectal cancer patients progressing after at least one previous line of chemotherapy: results of a phase ii single institution trial. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:455–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.BC Cancer Agency (bcca) BCCA Protocol Summary for Curative Combined Modality Therapy for Carcinoma of the Anal Canal Using Mitomycin, Capecitabine and Radiation Therapy. Vancouver, BC: BCCA; 2013. [Available online at http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/NR/rdonlyres/C0A8933B-3AAD-4EBAA95C-4552A0A060C9/63672/GICART_Protocol_1May2013.pdf; cited May 30, 2013). [Google Scholar]