Abstract

Background

There is interest in the use of health information technology in the form of personal health record (phr) systems to support patient needs for health information, care, and decision-making, particularly for patients with distressing, chronic diseases such as prostate cancer (pca). We sought feedback from pca patients who used a phr.

Methods

For 6 months, 22 pca patients in various phases of care at the BC Cancer Agency (bcca) were given access to a secure Web-based phr called provider, which they could use to view their medical records and use a set of support tools. Feedback was obtained using an end-of-study survey on usability, satisfaction, and concerns with provider. Site activity was recorded to assess usage patterns.

Results

Of the 17 patients who completed the study, 29% encountered some minor difficulties using provider. No security breaches were known to have occurred. The two most commonly accessed medical records were laboratory test results and transcribed doctor’s notes. Of survey respondents, 94% were satisfied with the access to their medical records, 65% said that provider helped to answer their questions, 77% felt that their privacy and confidentiality were preserved, 65% felt that using provider helped them to communicate better with their physicians, 83% found new and useful information that they would not have received by talking to their health care providers, and 88% said that they would continue to use provider.

Conclusions

Our results support the notion that phrs can provide cancer patients with timely access to their medical records and health information, and can assist in communication with health care providers, in knowledge generation, and in patient empowerment.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, personal health records, patient portals, electronic medical records

1. INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (pca) is a common and distressing disease. It may be life-threatening, but it is also considered a chronic condition because of the typically slow progression of the disease in most men. Patients with pca are often faced with difficult decisions about their care (for example, deciding on primary treatment for localized disease or on management of relapsed disease), and they commonly seek health information and access to their medical records [prostate-specific antigen (psa) results, for instance]. Research shows that there are gaps in providing health information to these patients1–6.

In a 2010 Health Council of Canada survey report7, patient engagement was perceived to be beneficial not only for patients, but also for providers and the health care system. One of the key enablers of engagement is information support. Patient engagement is also a fundamental component of the patient-centred care approach8. Several key attributes of the patient-centred care approach include shared decision-making, communication, self-management, and adherence9,10. Many cancer patients want to take a more active role in their care and wish to be kept well informed.

The sharing and use of health information in industrialized countries has undergone transformation in recent years, with the use of contemporary health information technologies (hits) such as electronic medical records, clinical information systems, Internet, and telehealth. For example, some component of an electronic health record is used for approximately 50% of Canadians11, and primary care offices have doubled the use of electronic medical records since 200512. The hits have traditionally been geared to meeting the needs of health care providers, researchers, and administrators. However, interest in the use of hit for patients and the public is now growing.

Early adoption of hit by patients and the public began with the use of the Internet to retrieve general health-related information13. More recently, personal health record (phr) systems have been viewed by some as a means to improve the patient experience and outcomes by empowering and engaging patients in a way that may assist with information gathering, decision-making, knowledge generation, and coping14. The concept of a phr maintained by the patient is not new; in medical journals, it dates back as far as 195615. A computer-based phr system was first described in the 1970s16. The contemporary definition of a phr is a secure electronic system that is owned by the patient and has the ability to incorporate health records in electronic form from multiple sources. For ease of access, phr systems can be Web-based. The term “patient portals” has also been used to describe phrs. Various types of phr have previously been described14. Although access to one’s medical record is the key attribute of a phr, many other functions can potentially be incorporated to serve the needs of patients and other designated users such as health care providers, family, and caregivers (see Table i). The phr might be regarded as the next step in the evolution of patient engagement in their own health care in the digital age.

TABLE I.

Potential functions of a personal health record system

| Show and share electronic medical records |

| Facilitate patient–provider communication or messaging |

| Generate alerts or reminders (e.g. vaccinations) |

| Show or request appointments |

| Provide a synoptic view of disease or condition |

| Show treatment history or planned treatments |

| Show medications and request refills |

| Provide decision-support tools |

| Provide tools for laboratory test monitoring |

| Show health information, either personalized or generalized |

| Provide tools for patient education or teaching (for example, multimedia) |

| Link to other (credible) Web sites or portals (that is, apomediation) |

| Provide tools for navigating the health care system |

| Show care plans (for example, for cancer survivorship) |

| Present patient questionnaires (for example, on quality of life, patient-reported outcomes) |

| Maintain a repository of personal data |

| Maintain a personal health organiser or diary |

| Provide tools for self-reporting or tracking (for example, biometrics, symptomatology) |

| Integrate with health tracking or monitoring devices (for example, in diabetes) |

| Integrate with Practice Portalsa |

| Facilitate health-related social networking |

| Provide access to peer support groups |

| Act as a study screening tool, provide access to research studies |

| Provide access to health services |

| Provide access to support services (for example, community-, office-, or institution-based) |

| Provide access to a health library |

| Act as a billing tool (for example, for use of personal health record or medical services) |

Practice Portal is a clinical information system for health care providers.

The purpose of the present study was to determine the experience of, and feedback from, pca patients using a phr called Prostate Cancer Internet-based Delivery System of Electronic Records (provider) while receiving care from a provincial cancer agency.

2. METHODS

The BC Cancer Agency (bcca) provides cancer care and research for the province of British Columbia and the Yukon Territory. The Vancouver Island Centre is one of the bcca’s regional cancer centres. The bcca uses an electronic clinical information system to store and access the medical records of cancer patients, scheduling and appointment information, and medications dispensed by the agency. The medical records include laboratory, pathology, imaging, operative, and procedure reports, transcribed notes dictated by health care providers, and correspondence from other providers. The bcca is an agency of the Provincial Health Services Authority, whose primary role is to provide access to specialized health care services. The Provincial Health Services Authority is the custodian of patient records at the bcca and is also responsible for information technology support.

Our study was a joint effort of the bcca and the School of Health Information Science at the University of Victoria. Ethics approval was received from the research and ethics boards from both organizations. The study, which ran from December 2007 to February 2009, involved the use and transmission of patient medical records over the Internet. To ensure that privacy, confidentiality, and security were maintained, the British Columbia Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research best practice guidelines on privacy were applied. A privacy impact assessment and a data-sharing agreement were completed with assistance from the Technology Development Office at the bcca and from a privacy and security consultant.

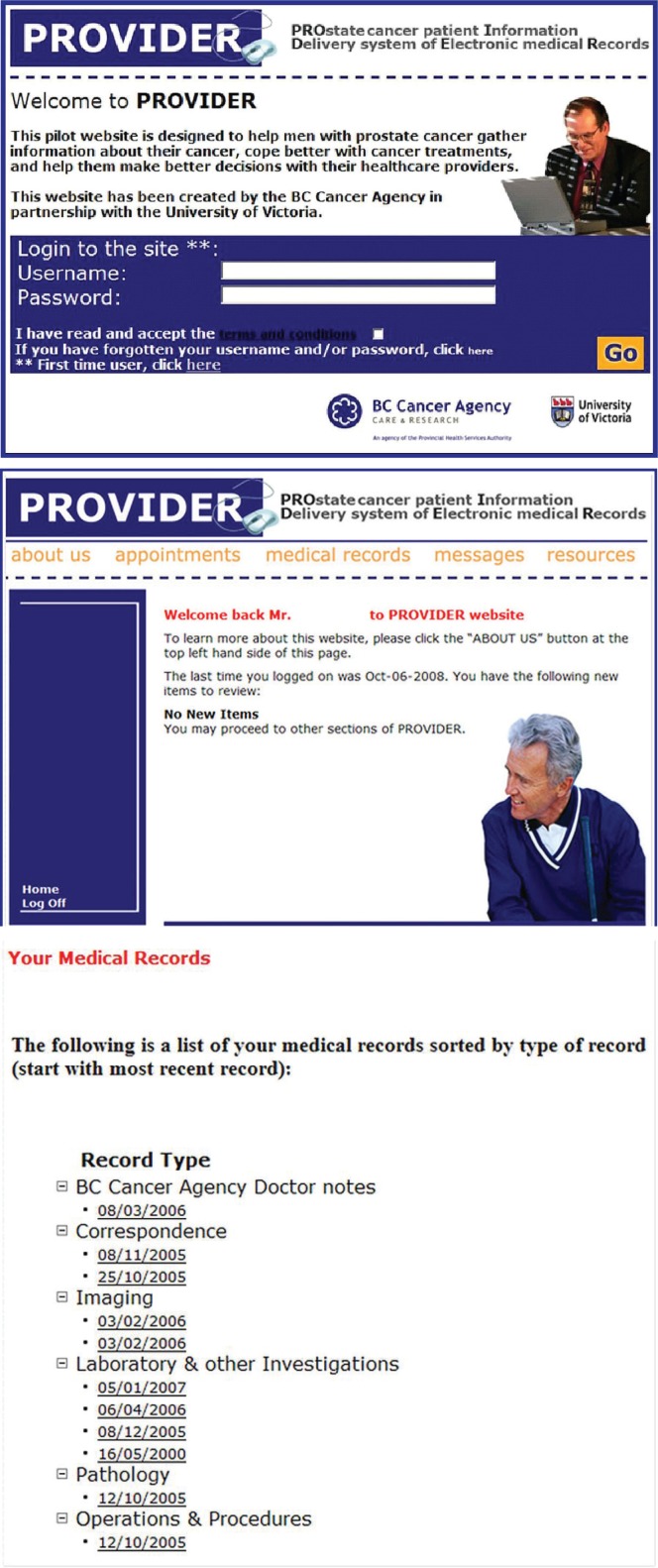

To determine if they were computer- and Internetready, all patients were required to provide informed written consent and to complete a questionnaire. A total of 22 men who had a histologically confirmed diagnosis of prostate adenocarcinoma and who were registered as patients at the bcca were given secure and private access to provider, where they could access their up-to-date medical record and a set of pcarelated support tools (Table ii). For the psa monitoring tool, psa results were entered manually by a research assistant. Figure 1 shows representative views of the provider Web site. An administrative module was also created for research assistants handling patient registration, data entry and transfer, content management within the phr, and phr activity monitoring.

TABLE II.

provider functions and usage patterns over a 6-month period

| Tool or function |

Times accessed or viewed

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | |

| View medical recorda | 19 | 1–39 |

| View synoptic summary of prostate cancer diagnosis | 3 | 0–15 |

| View cancer treatment received | 4 | 0–18 |

| View appointments at bcca | 4 | 0–27 |

| Request appointments at bcca | 0 | 0–5 |

| Use messaging tool | ||

| View list of cancer agency–dispensed medications | 3 | 0–12 |

| Use treatment decision-support tool | 6 | 0–35 |

| Use psa monitoring tool | 2 | 0–17 |

| Complete questionnaire on distress level | 5 | 0–18 |

| View hormone therapy slide presentation | 0 | 0–8 |

| Use patient-specific clinical trial and research study eligibility screening tool | 1 | 0–11 |

| Follow link to glossary of terms used in prostate cancer | 0 | 0–4 |

| Follow links to health information pertinent to prostate cancer | 1 | 0–7 |

| View list of recommended prostate cancer Web sites | 1 | 0–6 |

Includes transcribed doctor’s notes; correspondence from other health care providers; and laboratory, imaging, pathology, operative, and procedural reports.

bcca = British Columbia Cancer Agency; psa = prostate specific antigen.

FIGURE 1.

Sample screen images from the provider Web site.

The original plan was to host provider onsite at the bcca. However, that approach met with resistance from the chief information officer of the Provincial Health Services Authority because of concerns about privacy, information management and technology workload, and other overriding information management and technology priorities (previously described17). In the end, a compromise was reached whereby the electronic medical records from the cancer agency information system were printed in paper format by a research assistant, scanned back into electronic format as files in the Adobe Portable Document Format, and then transferred using a secure shell Internet transfer protocol to an offsite Linux-based Apache server system hosting provider at the University of Victoria Research Computing Facility (http://rcf.uvic.ca/). To be able to provide up-to-date medical records to study patients, new records were transferred every 2 working days using the process just described. To ensure that inappropriate records (for example, psychiatry-dictated notes, support services notes and reports) were not released, all patient medical records were reviewed by a qualified bcca Health Information Service clerk before being transferred to provider, in accordance with existing bcca policies for release of information to patients.

After completing a tutorial, study patients were given access to provider for a period of 6 months. They were asked to keep a diary of all communications and correspondence with health care providers at the bcca. At the end of 6 months, patients were asked to share their opinions on usability, satisfaction, and concerns with provider. The system automatically logged all access activity for each patient, including login attempts and the pages, functions, and tools accessed.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient Characteristics

The 22 patients who participated in the study had a median age of 64 years (range: 51–76 years), and 71% were married. All except 1 subject were white. Three quarters of the patients had a postsecondary school education or higher. Ten patients resided outside the limits of the city where the cancer centre is located. Two patients had metastatic disease. The 22 patients were at various phases of care when they enrolled in the study: 4 had not yet begun treatment for pca, 10 were in active treatment, 2 had completed treatment and were on follow-up, and 6 were experiencing a pca recurrence. All except 2 of the men reported prior regular use of a personal computer for more than 1 hour per week, with 55% reporting weekly use of at least 5 hours. In the past, 82% had searched the Internet for health information.

3.2. Overall PROVIDER Usage

Of 22 enrolled patients, 17 completed the study and end-of-study survey. Three patients did not use provider or complete the end-of-study survey. One patient completed the study, but not the end-of-study survey. One patient withdrew from the study because of illness.

The registered logins by patients over a 6-month period ranged from 0 to 47. The mean registered logins per month was 3.4, with the highest activity noted during the first month of use. For example, the median number of registered logins for each consecutive month was 5, 3, 1, 2, 0, and 1.

Table ii shows the patterns of use for specific provider features. Table iii shows the percentage of patients who reported using each feature. The 3 most commonly accessed features as reported by patients were medical records (94%), the appointment viewer (82%), and the psa monitoring tool (82%). The usage pattern as determined by the end-of-study audit (Table ii) confirmed that the most-used feature was access to medical records.

TABLE III.

Responses from end-of-study questionnaire and interviews with 17 patients

| Question or topic |

Patient responses (%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No response | Strongly disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neutral | Somewhat agree | Strongly agree | |

| Privacy and security | ||||||

| Privacy and confidentiality were maintained | 12 | 6 | 18 | 65 | ||

| Communication with physician | ||||||

| Communication with oncologist was better after using provider | 6 | 29 | 12 | 53 | ||

| Information in provider enhanced communication with oncologist | 6 | 12 | 29 | 53 | ||

| Prefer to see physician in person rather than use provider again | 24 | 29 | 41 | 6 | ||

| Health information and record access | ||||||

| Using provider, discovered new information that would have not been received by talking with health care team | 6 | 12 | 12 | 70 | ||

| Heath care team answered all questions and concerns | 6 | 24 | 70 | |||

| Very important medical records missing from provider | 6 | 47 | 24 | 18 | 6 | |

| Overall satisfaction with provider | ||||||

| Would use provider again | 6 | 6 | 6 | 82 | ||

| Would recommend provider to others | 18 | 82 | ||||

| provider answered all of my questions and concerns | 6 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 18 | 47 |

| Personal health record system was essential service to patients | 6 | 6 | 12 | 77 | ||

| Would be willing to pay user fee for use of personal health record system | 6 | 47 | 18 | 29 | ||

|

|

||||||

| Satisfaction level with specific provider functions | Did not use | Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | Excellent |

|

|

||||||

| View electronic medical records | 6 | 6 | 29 | 59 | ||

| View appointments at BC Cancer Agency | 18 | 18 | 18 | 47 | ||

| Request appointments | 88 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Messaging | 41 | 24 | 35 | |||

| Hormone therapy presentation | 77 | 6 | 18 | |||

| Clinical trial eligibility screening tool | 82 | 18 | ||||

| Distress questionnaire | 34 | 6 | 6 | 24 | 12 | 18 |

| psa monitoring tool | 18 | 12 | 6 | 65 | ||

| Links to other prostate cancer–related Web sites | 41 | 6 | 18 | 35 | ||

| General health information on prostate cancer | 52 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 24 | |

| Link to glossary of terms used in prostate cancer | 29 | 6 | 18 | 24 | 24 | |

psa = prostate specific antigen.

3.3. Medical Record Access

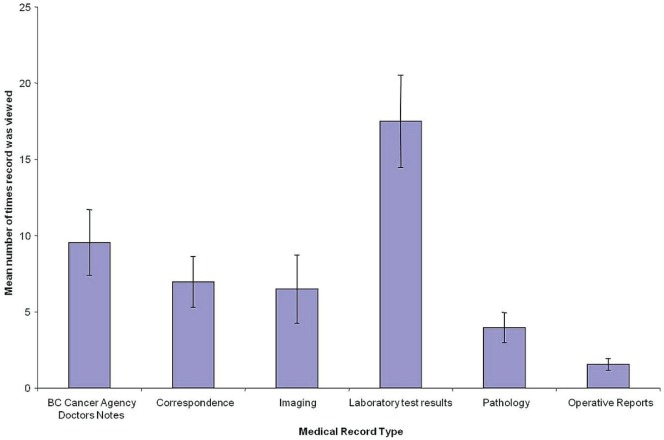

The total number of times that patients accessed their medical records over a 6-month period ranged from 1 to 39 (median: 19; Table ii). The total number of medical records viewed ranged from 0 to 111 (median: 45). As Figure 2 shows, the two most frequently viewed records were laboratory reports and transcribed doctor’s notes.

FIGURE 2.

Mean number of times specific types of medical records were viewed by patients (n = 17) using provider in a 6-month period.

3.4. Data Integrity, Operational Difficulties, Privacy, and Security

The 5 patients who reported problems or dissatisfaction with provider included 1 patient who reported an incorrect psa value in his psa monitoring tool (the value found to have been incorrectly entered by the research assistant). Another patient reported not having access to an operative report (the report had not been electronically signed off in the Cancer Agency Information System by the oncologist, thus delaying release to the patient). One patient complained about the printer-friendly report layout. Other patients reported dissatisfaction with the layout or design of the Web pages.

Several operational difficulties with the provider Web site were reported by patients or the research assistant:

One patient reported problems with requesting an appointment.

Two patients forgot their password, and one forgot the Web site address.

One patient reported that he could not log onto the provider Web site and had to restart his computer to do so.

One patient was unable to access his medical record on one occasion.

The provider Web site was not available for use on two occasions because the host server system was temporarily down.

No breaches of security or privacy with the use of provider were reported by patients, project team members, or the Research Computing Facility staff.

3.5. Patient Feedback

Patients were asked to complete a questionnaire and were interviewed at the end of their 6-month access period to obtain additional feedback. Patients were asked to refer to any notes they might have recorded in their diary. Table iii sets out the tabulated responses. Table iv shows additional comments from patients.

TABLE IV.

Selected end-of-study survey comments from patients (paraphrased)

| Transparency of medical records in provider builds trust between doctor and patient. |

| Highly valued having up-to-date access to medical records in order to do personal research and prepare for upcoming appointments with doctor. |

| Records helped to inform family members because family questions could be answered by showing them the reports. |

| provider was a useful reminder and reinforcer of what the doctor said during appointments. Another patient commented that remembering information at appointments with the doctor is challenging because of the time limitations. |

| Printout of medical record from provider was used for an out-of-province physician looking after the patient. |

| Results from imaging report created significant anxiety for patient’s spouse, which was later alleviated after a meeting with the physician. |

| Doctor’s notes and correspondence were found to be very insightful. |

| Patient felt more involved with his own care. |

| Patient was able to appreciate continuity of his health care. |

| Helped a patient appreciate how he was dealing with his cancer. |

| Government should acknowledge importance of personal health records. |

| Personal health record systems should be made publicly available. |

| Family physicians and urologists should have access to provider. |

| More interactivity with physician (for example, blogging) is desirable. |

| May be more useful for sicker patients. |

| Mixed responses with using distress monitoring tool and questionnaire. |

3.6. Satisfaction with PROVIDER

Asked to rate their overall satisfaction with using provider, patients responded 47% excellent, 41% very good, 12% good, 0% fair, and 0% poor. Of the study patients, 88% said that they would continue to use provider after study was completed; 12% were undecided or would not.

Patients were asked who they thought should be responsible for paying for a phr such as provider. The response options offered were federal government, provincial government, cancer agency (that is, health care providers), donations or charities, private industry, clients (that is, patients), and other. Responses were mixed, with more than one response often being entered. Although 47% of patients would be willing to pay for a phr (see Table iii), all patients felt that the government should help fund the phr.

4. DISCUSSION

It has been more than 20 years since the ruling by the Supreme Court of Canada that patients have a legal right to their medical records owned by their health care providers18. Traditionally, medical records are provided as paper copies. Health care providers are required to deliver the records within 30 days, which may defeat the goal of delivering them to patients in a time-sensitive fashion to assist with medical decision-making, coping, and self-care. An additional disincentive is that patients may be required to pay for administrative or copying fees to obtain the records. With the increasing use of hit, it seems intuitive to provide patients with access to their records by electronic means, which has distinct associated advantages and conveniences. However, the use of electronic records has raised new challenges and complexities: for example, the interpretation and application of privacy legislation, and the means to safely and effectively provide access to electronic records.

The present study is an example of a clinician-led, grassroots-style initiative within a large provincial-based tertiary cancer program. Patients with pca were chosen because they have a disease that is considered chronic and distressing. Leonard and Dalziel19 propose that patients with a chronic disease are well suited for adopting e-health solutions and have the most realizable return on investment. Patients with pca can exhibit high health information–seeking behaviour1,6,20–22, can perceive gaps in the health information they receive1–6, and often struggle with medical decision-making (for example, choosing treatment for localized pca).

In 2002, a series of interviews and surveys completed with pca survivors and their partners who attended local pca support group meetings sought to understand their health information needs and the ways in which they wanted to receive health information23. One of the key findings of that study was that 80% of the men, with a median age of 70 years, used computers and preferred to receive health information through electronic means. Patients desired access to all aspects of their medical record during all phases of their care. Other studies have similarly noted interest by patients for accessing their electronic medical record—even by patients considered more vulnerable or underserved24.

With limited research funding, the project team was able to successfully create and deploy a Web-based phr prototype. Considerable effort was required to address concerns about privacy, risk management, information technology resources, and hosting for the phr at the institutional level. The experience highlights a recommendation by the Canadian Committee for Patient Access to Electronic Health Records, which emphasized the need for “creation of structured approaches to change management within organizations to support the development of [patient-accessible] ehr”25.

The uptake and interest in patient-accessible electronic medical records varies across Canada, with more concerted efforts in academic centres and certain regions. In 2006, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto was the first Canadian site to offer patients virtual access to their medical records using a Web-based system called MyChart26. At October 2012, MyChart had more than 18,000 users27. Private industry has also been a stakeholder, largely led by telecommunications and Internet-based corporations that have created Web-based platforms to store and maintain health-related information for their own employees or in collaboration with academic centres and health care facilities—for example, HealthVault (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, U.S.A.).

Use of phrs will depend on the adoption rate of hit by health care providers. Although the use of hit in Canada has increased over time, Canada still lags far behind other countries such as the United Kingdom and New Zealand in full adoption of electronic records12,28,29. Significant barriers and gaps continue to challenge successful implementation on a large scale30–34.

In the present study, review of personal medical records was the most commonly used of all the available tools (Tables ii and iii). Important considerations in the provision of such records are how much should be provided35 and the health literacy or the ability of patients to comprehend and respond to their personal data, particularly when test results are unfavourable9. Most patients in our study felt that provider answered all their questions and concerns; they also said that they would use it again and would recommend it to others (Table iii). Clearly, the satisfaction level was positive, because all 17 patients who completed the study answered “good” to “excellent” for overall satisfaction. It should be noted, however, that 4 patients dropped out of the study and did not use provider or complete the end-of-study survey; their non-use could be interpreted as dissatisfaction with provider. An overall positive experience was similarly noted in a survey conducted with more than 4000 patients using a phr in United States36. Additionally, Chung et al.27 surveyed more than 2000 users of Sunnybrook’s MyChart and obtained results similar to those reported here.

Our study also highlights the potential harm of a phr when unfavourable test results are provided, as when one patient’s wife admitted to anxiety over an imaging report. Her concerns were later alleviated when the results were discussed with the oncologist. Conversely, prolonged waiting to receive or discuss unfavourable test results can also create great anxiety for patients. In the Chung study, only 7% of survey respondents would be willing to wait more than 10 days to receive a copy of their medical record; 38% wanted immediate access, and 27% wanted access before the physician had a chance to review the record. That last point is the most contentious among physicians. In a survey of 1972 patients at the Mayo Clinic, a similar rate of 38% of patients wanted immediate access to their test results; only 3% were willing to wait more than 2 days37.

Doctor’s notes were the second most commonly viewed medical record by patients in our study. Likewise, in the Chung study, transcribed reports were the second most commonly viewed electronic medical record. In a survey of 100 primary care physicians and more than 13,000 patients in the United States who had access to their doctor’s notes using an Internet-based phr9, patients were, like those reported here, generally satisfied with the access. Additionally, the study indicated that 60%–78% of patients reported improved adherence to medications after using the phr to view the doctor’s notes; a small group (1%–8%) became distressed after viewing the notes. Only a small percentage of the doctors surveyed reported increased workload (for example, longer office visits or more time addressing patient questions outside of visits) because of the phr.

A major concern over Web-based phrs is how to protect patient privacy and confidentiality, and the security measures required. Health care providers have a legal obligation to protect patient data. It was reassuring to note that no breaches occurred in the present study, and most patients did not have any overriding concerns about privacy. Other studies report a mixed level of privacy concerns associated with a phr. Although some studies showed that patients or the public express concerns about privacy, particularly in the United States24,38, a study by Patel et al.39 interestingly showed the opposite: patients perceived that privacy and security would be improved through the use of phrs. In studies in which patients actually used a phr, patients perceived that their privacy was preserved36, as was noted in our study. Physician concerns about privacy are also mixed. An additional concern from the provider perspective is liability associated with loss of privacy and misuse of patient data40.

Limitations of our study include a small sample size and the characteristics of that sample, which consisted mainly of well-educated white men who frequently used personal computers. The patient sample was also skewed in favour of those who had not yet begun treatment. Whether the benefits noted would apply to a larger, more diverse population of men with pca cannot be determined from the present study.

5. SUMMARY

Cancer patients tend to be high information seekers. Many want to be engaged in decision-making and self-care, and to feel empowered during their journey with cancer and as survivors.

Interest in Web-based phrs to meet the information needs of patients is growing, but has yet to go mainstream in Canada. It is expected that oncologists and other health care providers will increasingly have to address the question of patient access to their electronic medical record as more physician offices and health care facilities implement hit over time. This study using provider as a phr prototype demonstrated good uptake and satisfaction among pca patients. The results from our study support the need for further research and engagement of patients, health care providers, and other custodians of patient medical records.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this project was provided through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategic Training Program grant awarded to Dr. Francis Lau at the University of Victoria School of Health Information Science. The funding organization had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, nor approval of this publication.

The authors thank the following people for their assistance in making this study possible: Francis Ho md bsc, for his invaluable work in developing, coding, and deploying provider; the University of Victoria Research Computing Facility, for hosting provider; Nola M. Ries ba jd mpa llm, from the Faculty of Law and School of Health Information Science at the University of Victoria, for her work on the privacy impact assessment; Ms. Stephanie Soon, pharmacist at the bcca, for providing a hormone therapy PowerPoint presentation; Ms. Elaine Sawatsky, for her advice and expertise in health care privacy; Ms. Samantha Christy, Web communications specialist at the bcca, for her assistance with Web page design; Jack Littlepage phd, Professor Emeritus Biology, University of Victoria, and Charles Ludgate mb chb frcse md frcpc, retired radiation oncologist; and the Radiation Therapy Business Unit at the bcca, Vancouver Island Centre, for providing research assistant support.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Davison BJ, Degner LF, Morgan TR. Information and decision-making preferences of men with prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:1401–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison BJ, Goldenberg L, Gleave ME, Degner LF. Provision of individualized information to men and their partners to facilitate treatment decision making in prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:107–14. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snow SL, Panton RL, Butler LJ, Wilke DR, Bell DG, Rendon RA. Identification of an information gap for informed consent in early stage prostate cancer (pca). Proceedings from Canadian Urological Association, 59th Annual Meeting, Whistler, Canada. Can J Urol. 2004;11:2266. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snow SL, Panton RL, Butler LJ, et al. Incomplete and inconsistent information provided to men making decisions for treatment of early-stage prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;69:941–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Templeton HRM, Coates VE. Development of an education package for men with prostate cancer on hormone manipulation therapy. Clin Eff Nurs. 2003;7:33–42. doi: 10.1016/S1361-9004(03)00042-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Templeton H, Coates V. Informational needs of men with prostate cancer on hormonal manipulation therapy. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;49:243–56. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Council of Canada . How Engaged Are Canadians in Their Primary Care? Results from the 2010 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey. Toronto, ON: Health Council of Canada; 2011. Series: Canadian Health Care Matters, bulletin 5. [Downloadable from: http://www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/rpt_det_gen.php?id=148; cited April 18, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, Dearing KA. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:600–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delbanco T, Walker J, Bell SK, et al. Inviting patients to read their doctors’ notes: a quasi-experimental study and a look ahead. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:461–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross SE, Moore LA, Earnest MA, Wittevrongel L, Lin CT. Providing a Web-based online medical record with electronic communication capabilities to patients with congestive heart failure: randomized trial. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e12. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.2.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strasbourg D. Core elements of electronic health records in place for almost half of Canadians [Web page] Toronto, ON: Canada Health Infoway; 2011. [Available at: https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/index.php/news-media/2011-news-releases/core-elements-of-electronic-health-records-in-place-for-almost-half-of-canadians; cited April 18, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, et al. A survey of primary care doctors in ten countries shows progress in use of health information technology, less in other areas. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2805–16. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker L, Wagner TH, Singer S, Bundorf MK. Use of the Internet and e-mail for health care information: results from a national survey. JAMA. 2003;289:2400–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, Overhage JM, Sands DZ. Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:121–6. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dragstedt CA. Personal health log. J Am Med Assoc. 1956;160:1320. doi: 10.1001/jama.1956.02960500050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Computerisation of personal health records. Health Visit. 1978;51:227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnett J. The impact of privacy legislation on patient care. Int J Inf Secur Priv. 2008;2:1–17. doi: 10.4018/jisp.2008070101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McInerney v. McDonald, [1992] 2 SCR 138.

- 19.Leonard KJ, Dalziel S. How and when eHealth is a good investment for patients managing chronic disease. Healthc Manage Forum. 2011;24:122–36. doi: 10.1016/j.hcmf.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter N, Bryant–Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The supportive care needs of men with advanced prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:189–98. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldman–Stewart D, Brennenstuhl S, Brundage MD, Siemens DR. Overall information needs of early-stage prostate cancer patients over a decade: highly variable and remarkably stable. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:429–35. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong F, Stewart DE, Dancey J, et al. Men with prostate cancer: influence of psychological factors on informational needs and decision making. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:13–19. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(99)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pai HH, Lau F. Web-based electronic health information systems for prostate cancer patients. Can J Urol. 2005;12:2700–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhanireddy S, Walker J, Reisch L, Oster N, Delbanco T, Elmore JG. The urban underserved: attitudes towards gaining full access to electronic medical records. Health Expect. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00799.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiljer D, Urowitz S, Apatu E, et al. Patient accessible electronic health records: exploring recommendations for successful implementation strategies. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curtis J, Cheng S, Rose K, Tsai O. Promoting adoption, usability, and research for personal health records in Canada: the MyChart experience. Healthc Manage Forum. 2011;24:149–54. doi: 10.1016/j.hcmf.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung K, Cheng S, Leonard KJ, Dalziel S. Access to test results “The number one reason” why patients use a portal according to Sunnybrook MyChart users. Electron Healthc. 2012;11:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, Squires D, Peugh J, Applebaum S. A survey of primary care physicians in eleven countries, 2009: perspectives on care, costs, and experiences. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w1171–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silversides A. Canadian physicians playing “catch-up” in adopting electronic medical records. CMAJ. 2010;182:E103–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, et al. Use of electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1628–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0900592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGinn CA, Grenier S, Duplantie J, et al. Comparison of user groups’ perspectives of barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic health records: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:46. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rozenblum R, Jang Y, Zimlichman E, et al. A qualitative study of Canada’s experience with the implementation of electronic health information technology. CMAJ. 2011;183:E281–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sittig DF, Singh H. Electronic health records and national patient-safety goals. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1854–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1205420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Urowitz S, Wiljer D, Apatu E, et al. Is Canada ready for patient accessible electronic health records? A national scan. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halamka JD, Mandl KD, Tang PC. Early experiences with personal health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:1–7. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassol A, Walker JM, Kidder D, et al. Patient experiences and attitudes about access to a patient electronic health care record and linked web messaging. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11:505–13. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wendling P. Patients Want Online Access to Test Results Stat [Web article] Rockville, MD: Internal Medicine News; 2012. [Available at: http://www.internalmedicinenews.com/specialty-focus/practice-trends/single-article-page/patients-want-online-access-to-test-results-stat.html; cited April 18, 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dimitropoulos L, Patel V, Scheffler SA, Posnack S. Public attitudes toward health information exchange: perceived benefits and concerns. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:SP111–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel VN, Abramson E, Edwards AM, Cheung MA, Dhopeshwarkar RV, Kaushal R. Consumer attitudes toward personal health records in a beacon community. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:e104–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoffman S, Podgurski A. e-Health hazards: provider liability and electronic health record systems. Berkeley Technol Law J. 2009;24:1523–81. [Google Scholar]