Abstract

In the pre-vaccination era, diphtheria was a leading cause of childhood mortality. With the introduction of routine childhood immunization, paediatric care and improved hygiene status the disease has been almost completely eradicated in many developed countries. On the contrary developing countries, still account for 80–90% of the global burden. Retrospective analysis of 52 cases of diphtheria over a period of 12 years at a tertiary referral hospital was carried out. They were analyzed for mortality and morbidity trends, immunization status, microbiological confirmation rates and antidiphtheritic serum (ADS) administration. Incidence in those over 5 years was 59.61%. Only 11.54% cases were either partially or fully immunized. The case fatality rate was 36.53%. Culture was performed only in 17 cases whereas ADS was administered in only 16 cases. In conclusion, the occurrence of diphtheria even in those immunized highlights the flaws in the present immunization program. Poor immunization coverage, lack of ADS, antibiotic resistance are the main reasons for re-emergence of diphtheria.

Keywords: Corynebacterium diphtheria, Immunization, Antidiphtheritic serum, Mortality, Re-emergence

Introduction

Diphtheria is a potentially fatal acute disease caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. In the pre-vaccination era, diphtheria was a leading cause of childhood mortality [1, 2]. Forty percent of the cases occurred in children below 5 years and 70% below 15 years of age [1]. The disease has been almost completely eradicated in many developed countries and in many European countries no cases have been reported for almost a decade and in the USA only 45 cases were reported during 1980–1995 [3].

On the contrary, in developing countries, although the incidence has drastically declined, still account for 80–90% of global burden. Disease in these countries affects both children and young adults [2]. Because of the inappropriate reporting, true number of diphtheria cases and deaths are unknown [4]. The present paper, a retrospective study is an attempt to highlight the problems faced by developing countries in tackling the menace of diphtheria.

Materials and Methods

The present study is based on the retrospective analysis of the records available from 1997 to 2009 at a tertiary referral hospital. The data was obtained from the hospital medical records section by searching for cases diagnosed as Diphtheria. A total number of 52 cases were studied which included suspected, probable and confirmed cases of diphtheria as per the WHO definition guidelines [5].

Aims and objectives were:

To identify the mortality and morbidity trends of diphtheria.

To study the immunization status of affected children.

To know the microbiological confirmation rates.

To study the data regarding antidiphtheritic serum (ADS) administration.

Difficulties in managing a proven case.

Results

Twenty one patients (40.38%) were less than 5 years and 31(59.61%) were over 5 years which included four patients who were over 17 years. Twenty four (46.15%) were males and 28 (53.84%) were females.

Morbidity and Mortality

Case fatality rate There were 19 deaths with a case fatality rate of 36.53%. Among the 19 deaths, 9 cases were that of children over the age of 5 years.

Immunization Status of the Affected Children (Table 1)

Table 1.

Immunization status and deaths

| Immunization status for diphtheria | Number of cases | Deaths (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Immunized | 6 | 1 (16.67) |

| Non immunized | 30 | 16 (53.33) |

| Not known | 16 | 2 (12.50) |

| Total | 52 | 19 (36.54) |

Six cases (11.54%) were immunized either fully or partially and 30 cases (57.69%) were non immunized. In 16 cases (30.77%) the immunization status was not known. Incomplete immunization has been considered as non immunized status.

The number of sub sites involved in the immunized and non immunized individuals is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Immunization status versus the number of sub sites involved

| Immunization status for diphtheria | Up to two sub sites | More than two sub sites | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunized | 6 (22.22%) | 2 (8%) | 8 (15.38%) |

| Non immunized | 18 (66.66%) | 20 (80%) | 38 (73.07%) |

| Unknown status | 3 (11.11%) | 3 (12%) | 6 (11.53%) |

| Total | 27 | 25 | 52 |

Microbiological Confirmation Rates

Albert staining was performed in 46 cases of which 29 (63.04%) cases were positive. Culture was performed in 17 cases of which eight were positive. In the remaining 35 (67.30%) cases culture was not performed. In the remaining six cases neither staining nor culture was performed (falls into suspected or probable case of diphtheria as per the WHO definition guidelines) [5].

Antidiphtheritic Serum (ADS) Administration

ADS was administered in 16 of the total 52 cases. In 11 of these 52 cases the outcome was not known. Outcome was analyzed for ADS administration leaving out the cases where outcome was not known (Table 3).

Table 3.

ADS administration and the outcome of cases

| ADS administration | Death | Survival | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administered | 5 (26.31%) | 8 (36.36%) | 13 (31.70%) |

| Not administered | 14 (73.68%) | 14 (63.63%) | 28 (68.29%) |

| Total | 19 | 22 | 41 |

Discussion

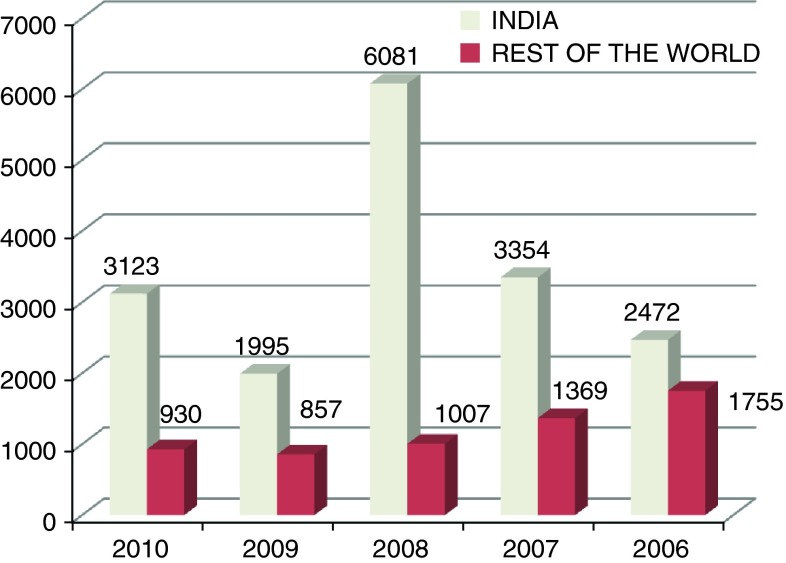

In the last 5 years there is a resurgence of diphtheria and India has accounted for 3,123 cases of the total of 4,053 cases (77.05%) reported in the world in 2010. The trend of the diphtheria cases in the past 5 years in India and rest of the world can be seen in Fig. 1. There have been numerous reports from different parts of India (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the total number of diphtheria cases reported in India and rest of the world in last 5 years [30]

Table 4.

Previous studies reporting diphtheria cases in India

| Authors | Place (year) | Design of study and sample size | Salient features | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Singhal et al. [14] | New Delhi (2000) | Prospective study; 10 cases | Six cases: Acute phase Four cases: Cardiac/neurological complication |

Immunization coverage not satisfactory To establish good surveillance |

| 2. | Sharma et al. [20] | In & around Delhi (2007) | Retrospective study (1998–2004); effective sample size of 493 cases | 6.7% were >9 years 44% were between 5 and 9 years Unknown: 24% Unvaccinated: 70% |

By adopting WHO recommended methods, cases of diphtheria can be identified rapidly and correctly |

| 3. | Patel et al. [22] | Gujarat (2004) | Retrospective Study; 188 cases | Case fatality rate: 0.0% (1994–1995) to 42.9% (1993); 18.6% in 2002 Immunization : (details of only 107 cases available) 3.73% immunized; 30.84% partially immunized; 65.42% not immunized |

Declining/low immunization coverage, naturally waning of immunity against diphtheria are the major factors for resurgence |

| 4. | Murhekar et al. [15] | Hyderabad (2009) | Cross sectional study; 11 clusters | Primary & booster coverage was in <80% 56% were immune |

Booster coverage & immunity low among Muslims |

| 5. | Nandi et al. [28] | Assam (2003) | Retrospective study; 101 cases | 30% vaccinated 65% microbial confirm rate |

Poor immunization coverage |

| 6. | Bitragunta et al. [16] | Hyderabad (2008) | Community based prospective study (2003–2006) | Rise of annual incidence (per one lakh) from 11 (2003) to 23 (2006) | Muslim population were affected in majority (70%) |

| 7. | Dravid and Joshi [29] | Malegaon and Dhule regions of north Maharashtra (2008) | Prospective study; 30 out of 86 throat swabs and 63 out of 202 throat swabs were positive by culture | Rising number of isolated cases since 2005 | Resurgence of diphtheria is highlighted |

In the rural areas patients are managed by general practitioners mainly and by the time patient reports to tertiary care hospital more number of sub sites would be involved. In the present study the number of sub sites involved was invariably more in the non immunized individuals and where the immunization status was not known.

In the present study Albert staining was relied upon for detection of diphtheria although culture is the definitive investigation which was performed only in 17 cases of which 8 were positive. The microbiologically confirmed cases range from 7 to 21% in various studies [6, 7]. Reason why the microbial investigations were not performed in majority of the cases were not known.

However in a retrospective study conducted at Delhi where initially microbiologically confirmed cases was 26.3% in 1998 rose to 64.9% after adopting WHO recommended methods of detection [8]. However, still many places in India lack basic diagnostic facilities. Many times the throat swab is not taken from the representative area which may give negative results.

Only 16.67% of the patients in the present study were immunized for diphtheria and the rest were either non immunized or the status of immunization was not known. As in the present study, cases occurring even in the immunized individuals highlight the defect in the whole process of immunization. There is a significant drop out between the 1st and 3rd dose of OPV/DPT in different parts of India [9]. There has been no provision to trace the vaccine drop outs [8, 10]. Poor immunization coverage has been attributed to the poor vaccination services, low awareness among parents and inaccessibility of health centres [10, 11].

Many authors have highlighted deteriorating health infrastructure, adoption of an alternative schedule of few doses of low antigenic strength and administration of the second childhood booster at 9 years instead of 6 years [1]. Any drop in childhood immunization coverage may trigger an epidemic and hence adult booster dosages may be necessary. In some situations child may not be vaccinated despite being in contact with the health facility and is termed as “missed opportunities”. This might have resulted from short supply of vaccine, poor clinic organization, non availability of immunization services on all days of a week, inadequate screening for immunization status of the children visiting the health facility, not opening a multidose vial if enough children are not present and delaying or postponing vaccination for minor childhood illnesses [9, 12].

There was variability of vaccine coverage significantly between urban and rural areas, paucity of recent data, immunization coverage by independent surveys is lower than what official claims indicating flaw in collection and compilation of data and low booster coverage at 1½ and 5 years [10]. Other factors might be the quality issues like cold chain maintenance which might have affected efficacy [13]. Widespread illiteracy among care providers regarding the importance of vaccination, its schedules and knowledge about vaccine preventable diseases in addition to ineffective dissemination of health information has been largely attributed to low immunization [9, 13].

Still other factors attributable are poor logistic organization, poor screening facilities, ignorance about total doses required, improper or absent counseling, vaccine side effects and migration of families [9, 10].

A minimum immunization coverage of 90% in children and 75% in adults is required to prevent spread of diphtheria [13]. Overcrowding and migrant population with low immunization coverage are the potential risk factors [14]. The proportion of children immune to diphtheria as well as booster coverage was low among muslim population [15]. This has been attributed to either a poor offer of vaccine by health services or poor demand of vaccine in the community. This fact was also supported by another study [16] which found 70% to be Muslims among 2,685 cases of diphtheria and had 3 times higher risk than other communities.

There does not exist any surveillance system for vaccine preventable diseases except for poliomyelitis in India. While polio causes debility, diphtheria can be dangerous and associated with high mortality. Many families accept pulse polio as a substitute for routine immunization in the absence of adequate awareness [8]. Statistics on diphtheria was taken essentially from primary health centre which would only be a small fraction of the total. There is a need for simple, practical, inexpensive, real time disease surveillance, using the district as a unit, covering both public and private sector medical care establishments [17].

Isolation of diphtheria cases is poor and ranged from 0 to 14.7% [18] but increased from 3% in 1995 to 36% in 2001 [19]. As secondary attack rate is very high all cases needs to be isolated and their family members thoroughly examined. The school where the child studied need to be examined for the possible exposed individuals.

There is an age shift of occurrence recently and 40–45% were above the age of 5 years [6]. This was initially noted in Russian epidemic and China outbreak but however for the first time in India similar observations were made in a study by Sharma [20]. The present study supports the study with 59.61% of the patients who are above the age of 5 years.

Case fatality rate in the present study was 36.53% where as it ranged from 32 to 56.3% in different centers in north India [9, 18, 21], and 42.9% in west India [22]. This higher case fatality was attributed to non availability of antitoxin in India [7, 18, 21, 23]. This may also be due to delay in diagnosing the cases.

Antibiotics still play a very important role in the mild forms of diphtheria. However, drug resistance has been observed to Penicillin, Chloramphenicol, Erythromycin, Tetracycline and Ampicillin in various studies in India [24–26].

Before the introduction ADS, case-fatality rates from some diphtheria outbreaks reached or exceeded 50% [27]. However with introduction of antitoxin, morbidity and mortality have come down drastically in majority of the developed countries. Although ADS needs to be given on strong suspicion of diphtheria even without waiting for microbiological confirmation, it was given only in eight of our cases and was largely due to the non availability and cost factor.

It is important that all cases are notified and health authorities take suitable measures by concentrating on the community where the case was reported.

Conclusion

Diphtheria morbidity and mortality continues to be high in India. There is an age shift in the occurrence of diphtheria increasingly over 5 years of age. High and sustained vaccination coverage, booster dosage and prevention of dropouts are essential to control diphtheria. The focus on diphtheria vaccination should be with as much zeal and dedication as is with polio vaccination. Obstacles to optimal vaccine delivery must be identified and forceful measures are to be taken to improve immunization coverage. Village health workers are to be trained to identify the suspected cases, in the same way as they identify acute flaccid paralysis with respect to polio. Basic laboratory facilities should be made available for early diagnosis. ADS is life saving and should be made available.

Acknowledgments

The study was conducted at Karnataka Institute of Medical Sciences, Hubli which is a tertiary referral hospital located in the North Karnataka. We sincerely thank the Department of Medical Records, Department of Microbiology and the Department of Paediatrics for procurement of the data for analysis.

Contributor Information

Manjunath Dandinarasaiah, Phone: +91-836-2271210, FAX: +91-9900520748, Email: drmanjud@gmail.com.

Bhat Kemmannu Vikram, Email: entvikram@rediffmail.com.

Naveen Krishnamurthy, Email: naveenk1381@gmail.com.

A. C. Chetan, Email: ac.chetan@gmail.com

Abhineet Jain, Email: abhineetjn@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Vitek CR, Wharton M. Diphtheria in the former Soviet Union: reemergence of a pandemic disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:539–550. doi: 10.3201/eid0404.980404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galazka AM, Rabertson SE. Diphtheria: changing patterns in the developing world and industrialized world. Eur J Epidemiol. 1995;11:107–117. doi: 10.1007/BF01719955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitek CR, Wenger J. Diphtheria. Bull WHO. 1998;76(Suppl 2):129–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park K. Park’s text book of preventive and social medicine. 20. Jabalpur: M/s Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Begg N. Diphtheria—manual for the management and control of diphtheria in the European region. Copenhagen: WHO Publication; 1994. p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray SK, Das Gupta S, Saha I. A report of diphtheria surveillance from a rural medical college hospital. J Indian Med Assoc. 1998;96(8):236–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayashree M, Shruthi N, Singhi S. Predictors of outcome in patients with diphtheria receiving intensive care. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(2):155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair TN, Varughese E. Immunization coverage of infants—rural–urban difference in Kerala. Indian Pediatr. 1994;31(2):139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Family Welfare Annual Report-1998–1999 (1999) Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, pp 63–71

- 10.Singh J, Ichhpujani RL, Prabha S, et al. Immunity to diphtheria in women of child bearing age in Delhi in 1994: evidence of continued Corynebacterium diphtheriae circulation. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1996;27(2):274–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukherjee B, Ray SK, Kar M, Mandal A, Mitra J, Biswas R. Coverage evaluation surveys amongst children in some blocks of West Bengal. Indian J Public Health. 1990;34(4):209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nivsarkar N, Pathak AA, Thakar YS, Saoji AM. Study of diphtheria antibody levels in healthy population. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1994;37(4):421–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Icchpujani RL, Grover SS, Joshi PR, Kumari S, Verghese T. Prevalence of diphtheria and tetanus antibodies in young adults in Delhi. J Commun Dis. 1993;25(1):27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singhal T, Lodha R, Kapil A, Jain Y, Kabra SK. Diphtheria—down but not out. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37(7):728–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murhekar MV, Bitragunta S, Hutin Y, Chakravarty A, Sharma HJ, Gupte MD. Immunization coverage and immunity to diphtheria and tetanus among children in Hyderabad, India. J Infect. 2009;58(3):191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bitragunta S, Murhekar MV, Hutin YJ, Penumur PP, Gupte MD. Persistence of diphtheria, Hyderabad, India, 2003–2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(7):1144–1146. doi: 10.3201/eid1407.071167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.John TJ. Resurgence of diphtheria in India in the 21st century. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128(5):669–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lodha R, Dash NR, Kapil A, Kabra SK. Diphtheria in urban slums in north India. Lancet. 2000;355(9199):204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04847-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma NC, Tiwari KN, Panda RC, Dhillon R (2002) Diphtheria status in India and data from a sentinel centre in Delhi, India. In: Proceeding of the 7th international meeting of the European laboratory working group on diphtheria (ELWGD), Vienna, Austria, 12–14, 2002, p 48

- 20.Sharma NC, Banavaliker JN, Ranjan R, Kumar R. Bacteriological and epidemiological characteristics of diphtheria cases in and around Delhi—a retrospective study. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126(6):545–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh J, Harit AK, Jain DC, et al. Diphtheria is declining but continues to kill many children: analysis of data from a sentinel centre in Delhi, 1997. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;123(2):209–215. doi: 10.1017/S0950268899002812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel UV, Patel BH, Bhavsar BS, Dabhi HM, Doshi SK. A retrospective study of diphtheria cases, Rajkot, Gujarat. Indian J Med Res. 2004;29:161–163. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dittmann S, Wharton M, Vitek C, et al. A successful control of epidemic diphtheria in the states of the former union of Soviet Socialist Rupublics: lessons learned. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 1):510–522. doi: 10.1086/315534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayyagari A, Venugopalan A, Ray SN. Studies on diphtheria infection in and around Delhi. J Indian Med Assoc. 1975;65(12):328–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dutta JK, Ayyagari A, Gautum AP, Chadha SK, Ray SN. A comparative study of bacteriologically probed and clinically diagnosed (culture negative) cases of diphtheria. J Indian Med Assoc. 1976;67(11):241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayyagari A, Venugopalan A, Ray SN. Studies on cutaneous diphtheria in and around Delhi. Indian J Med Res. 1977;65(1):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weekly epidemiological record (2006, Jan 20) WHO, Geneva, pp 24–32. http://www.who.int/wer/2006/wer8103.pdf. Updated 2011, Jan 7; cited 2011, Sep 4

- 28.Nandi R, De M, Browning S, Purkayastha P, Bhattacharjee AK. Diphtheria: the patch remains. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117(10):807–810. doi: 10.1258/002221503770716250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dravid MN, Joshi SA. Resurgence of diphtheria in Malegaon and Dhule regions of north Maharashtra. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127(6):616–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Immunization surveillance, assessment and monitoring—date, statistics and graphics by subject (2011, Sep 5) WHO Publication, Geneva. http://www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/data/data_subject/en/. Updated 2011, July 22; Cited 2011, Sep 21