Abstract

Two pension reforms in Austria increased the early retirement age (ERA) from 60 to 62 for men and from 55 to 58.25 for women. We find that raising the ERA increased employment by 9.75 percentage points among affected men and by 11 percentage points among affected women. The reforms had large spillover effects on the unemployment insurance program but negligible effects on disability insurance claims. Specifically, unemployment increased by 12.5 percentage points among men and by 11.8 percentage points among women. The employment response was largest among high-wage and healthy workers, while low-wage and less healthy workers either continued to retire early via disability benefits or bridged the gap to the ERA via unemployment benefits. Taking spillover effects and additional tax revenues into account, we find that for a typical birth-year cohort a one year increase in the ERA resulted in a reduction of net government expenditures of 107 million euros for men and of 122 million euros for women.

Keywords: Retirement age, policy reform, labor supply, disability, unemployment

Aging populations put enormous pressures on public pension systems.1 These financial pressures are further enhanced by low and decreasing labor force participation rates of older individuals. As a consequence, many countries are considering (or have already implemented) pension reforms that cut retirement benefits and/or increase the statutory retirement age.2

Policy reforms that increase the statutory retirement age are difficult to implement for two main reasons. A first objection holds that increasing the statutory retirement age is not an effective policy instrument because the employment opportunities of older workers are weak. Increasing the retirement age is therefore unlikely to increase employment of older workers. Instead, it will increase unemployment-benefit and disability-benefit payrolls. Second, increasing the statutory retirement age is unfair because it mainly restricts the opportunity set of workers with the weakest labor market position while not restricting unaffected workers whose labor market conditions are more favorable. Put differently, the less healthy workers in low-paid jobs (with the highest incentive to retire) are hurt while the retirement age is less binding for workers in good health in well-paid jobs.

In this paper we shed new light on these controversial issues by exploiting policy variation from two pension reforms in Austria. These reforms implemented an increase in the early retirement age (ERA) by 2 years for men and 5 years for women.3 The increase in the ERA was phased in gradually starting in the year 2001 and will end in 2017. This paper restricts attention to the early part of this policy change. Between the years 2001 and 2010, the ERA was increased from age 60 to 62 for men and from age 55 to 58.25 for women.

Our study has three main objectives. First, we study to which extent the increase in the ERA turned out to be an effective tool to increase employment of older workers. A series of previous studies on the relationship between social security provisions and retirement have documented a sharp increase in labor market exits at the age of first eligibility for retirement benefits (Gruber and Wise, 2007). Given this empirical regularity, an increase in the ERA is likely to be effective in delaying labor market exit and increasing employment of older workers.

A second main objective of our analysis is to investigate the importance of spillover effects of the ERA increase into other social insurance programs, in particular, unemployment insurance (UI) and disability insurance (DI). For instance, previous studies have found that UI and/or DI payrolls are often used as a gateway to early retirement. In many countries, enrollment in these programs has increased substantially in recent years and they have become an important channel by which workers drop permanently out of the work force.4 Understanding how a rise in the ERA affects inflow into other programs is also important to assess the consequences for government expenditures.

A third main objective of our analysis is therefore to explore the fiscal consequences (i.e. net reduction of government expenditures) of the increase in the ERA. More precisely, we estimate the impact of the ERA reforms on retirement benefit payments, social security contributions and income taxes as well as changes in UI and DI benefit payments. Since the increase in ERA may affect labor market behavior already prior to reaching the ERA as well as above the ERA, it is important to account for these effects to correctly estimate the fiscal consequences.

We think that understanding the consequences of the pension reforms in Austria is of general interest. The institutional features of the Austrian old-age social security, while differing in the details, share many features in other countries. In many public pension systems there is both an ERA and a NRA. Moreover, many countries allow older workers to permanently retire through UI and DI, often providing preferential treatment for older workers. We therefore think that evaluating the Austrian pension reforms will contribute to a better understanding of pension reforms in other contexts. In addition, we can exploit the Austrian social security administration database (ASSD) which covers the universe of all private sector workers. The ASSD not only reports the complete employment- and earnings-history of these workers, it also provides information about the take-up of other welfare benefits (such as UI and DI benefits). Hence, we can study not only the labor market consequence but also the fiscal implications of the ERA increase in a clean way.

To identify the effect of the ERA on the labor market behavior of older workers, we exploit the gradual phasing-in of the ERA increase, implying that quarter-of-birth is key for determining the age of first eligibility for retirement benefits. As the ASSD reports individuals’ birth month, we can precisely determine each individual's ERA and hence estimate the effects of the ERA increase by comparing the labor market behavior of younger birth cohorts to older birth cohorts who were not affected by the rise in the ERA.

Our empirical analysis yields the following results. First, we find that the increase in the ERA had a positive but relatively modest employment effect. Our estimates indicate that increasing the ERA by one year increases employment during that year by 9.75 percentage points among men and 11 percentage points among women. These estimates reflect the short run employment effects of the ERA increase. The longer-term effects of this policy change may differ given that younger birth cohorts who know further in advance that their ERA will be higher may start to smooth their consumption earlier on. This would likely reduce the employment response of the ERA increase in the long-run.

Second, a closer look on the take-up of welfare benefits shows that increasing the ERA causes a substantial increase in registered unemployment; 12.51 percentage points among men and 11.77 percentage points among women. The increase in the percentage of people on disability benefits is comparably small in magnitude. We also find that behavioral responses vary considerably across workers. The employment response is largest among healthy, high-wage workers while low-wage workers in poor health either retire through the DI program or bridge the gap to the new ERA by drawing on unemployment benefits.

Finally, we explore the fiscal consequences of the ERA reforms. Increasing the ERA reduces retirement benefit payments and raises income and payroll tax revenues, thus reducing the government's financial burden. However, the savings in government expenditures are partially offset by additional expenditures in the UI and DI programs due to spillover effects. We estimate that, for a typical birth-year cohort, increasing the ERA by one year generates a net reduction in government expenditures of 107 million euros for men and 122 million euros for women. This calculation takes into account that behavioral responses may not only occur during the year when the individual reaches the ERA, but also during the years before and after.

Our paper is related to an extensive literature studying how changes in benefit generosity affect the timing of retirement (Burtless, 1986; Krueger and Pischke, 1992; Börsch-Supan and Schnabel, 1998; Coile and Gruber, 2007; Liebman et al., 2009; Manoli and Weber, 2010). Those studies typically find that changes in retirement benefits can have significant impacts on the timing of retirement. In contrast, there is little work on how a rise in the retirement age affects labor force participation.

Furthermore, earlier studies have relied on out-of-sample predictions to estimate the labor supply response to changes in the ERA and NRA and typically find that raising the retirement age leads to a sizeable increase in labor force participation of older workers (Rust and Phelan, 1997; Panis et al., 2002; Gruber and Wise, 2004). More recently, Mastrobuoni (2009) exploits a policy change in the U.S. that increased the NRA from 65 to 67 and raised the penalty for claiming retirement benefits before the NRA. He concludes that an increase in the NRA by 2 months delays effective retirement by around 1 month. This estimate is much larger than the effect suggested by the previous simulation studies, possibly because the out-of-sample projections omit factors that are important for the timing of retirement such as social custom or liquidity constraints.

Our paper estimates the labor supply response of an increase in the ERA as opposed to the NRA. This distinction is important for two reasons. First, an increase in the ERA forces individuals to claim retirement benefits later (or seek benefits from other sources) while an increase in the NRA is equivalent to a reduction in benefits. Second, the documented peak in the age distribution at retirement is typically more pronounced at the ERA as opposed to the NRA (Gruber and Wise, 1999). Therefore, a rise in the ERA is likely to be a more effective measure to increase labor force participation among older workers as opposed to a rise in the NRA.

This paper also builds on a growing literature that explores how changes in the generosity of one social insurance program affects enrollment in other programs. Most of these studies focus on spillover effects of changes in DI programs (Autor and Duggan, 2003; Karlström et al., 2008; Borghans et al., 2010; Staubli, 2011) or UI programs (Lammers et al., 2013; Inderbitzin et al., 2013). The most closely related paper is by Duggan et al. (2007) who study the same policy change as Mastrobuoni (2009) and find that the increased penalty for claiming retirement benefits before the NRA led to more DI enrollment prior to the NRA. Our findings suggest that the increase in the ERA had a relatively small effect on disability receipt. Instead we find that a significant fraction of affected individuals responded to the increase in the ERA by claiming unemployment benefits or staying in employment longer.

This paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes Austria's social insurance programs and the policy changes in the public pension system. Section 3 summarizes the data and presents descriptive statistics. Section 4 outlines the identification strategy. Section 5 presents the empirical results. Section 5.3 explores the implications of the reforms on net government expenditures. Section 6 draws conclusions.

2 Background

2.1 The Public Pension System in Austria

The Austrian public pension system covers all private sector workers and provides early retirement pensions, old age pensions, and disability pensions. These pensions provide the main source of income in retirement. The level of benefits depends on a “assessment basis” and a “pension coefficient”. The assessment basis corresponds to the average earnings over the best 15 years after applying a cap to earnings in each year. The pension coefficient is the percentage of the assessment basis that is received in the pension. The pension coefficient increases with the number of insurance years up to a maximum of 80% (roughly 45 insurance years).5 Insurance years comprise both contributing years (periods of employment, including sickness, and maternity leave) and qualifying years (periods of unemployment, military service, or secondary education). Since 1996 there is a penalty for claiming benefits before the NRA and a bonus for retirement after the NRA of approximately 2 percentage points per year. All pensions are subject to income taxation and mandatory health insurance contributions. The replacement rate after income and payroll taxes is on average 75% of the pre-retirement net earnings.

Early retirement pensions can be claimed at any age after 60 for men and 55 for women, conditional on having 35 contribution years or 37.5 insurance years. In 2000, around 88% of men and 54% of women satisfied this requirement when they reached the ERA. Old age pensions can be claimed at the NRA of 65 for men and 60 for women as long as an individual has 15 insurance years in the last 30 years or 15 contribution years. To be eligible for a disability pension, applicants must suffer a health impairment that will last for at least 6 months and must have accumulated at least 5 insurance years in the last 10 years. Individuals who satisfy the eligibility criteria for an early retirement pension or an old-age pension are not allowed to apply for a disability pension. In contrast to public pension systems in many other countries, disability beneficiaries are not automatically shifted to the old-age pension program at the NRA.6

Because medical criteria for disability classification are relaxed starting at age 57, disability pensions play an important role in early retirement (Staubli, 2011). More specifically, below that age threshold, an individual is generally considered disabled if the capacity to work is reduced by more than 50% in any occupation in the economy. Above the age threshold of 57 the same individual qualifies for benefits if the work capacity is reduced by 50% in the same occupation. As a direct consequence, disability enrollment rises significantly beginning at the age threshold.7 Because men first become eligible for early retirement pensions at age 60 as opposed to 55 for women, disability enrollment is disproportionately higher among older men.

Beneficiaries of an early retirement pension may continue to work provided that their earnings fall below an exempt amount (around 380 euros per month). If the monthly earnings exceed the exempt amount, benefit payments are entirely withdrawn in that month. These strict earnings restrictions are abruptly relaxed at the NRA; beneficiaries older than the NRA can earn as much as they want without losing their benefits. Earnings restrictions are more relaxed for DI claimants, given that they will only lose a fraction of their benefits (at most 50%) if their earnings exceed the exempt amount.

The UI program plays an important role in the transition to early retirement in Austria. Many older workers stop working before the eligibility age for an early retirement pension and bridge the gap via unemployment benefits (Inderbitzin et al. (2013)). Unemployment benefits are not taxed and replace around 55% of the last net wage, subject to a minimum and maximum (though only a small fraction of individuals are at the maximum). Depending on the previous work history, unemployment benefits can be claimed for up to one year. Individuals who exhaust their regular unemployment benefits may apply for unemployment assistance, which pays a lower level of benefits indefinitely. These means-tested transfers can be at most 92% of regular unemployment benefits, but are reduced euro for euro with the amount of any other family income.

In January 2000 the Austrian government introduced a partial retirement scheme, allowing for a gradual transition from work to retirement. Conditional on having worked for 15 years in the past 25 years, male workers older than 55 and female workers older than 50 can reduce their working time to 40-60% of their previous work hours for a maximum period of five years while their earnings are only reduced to 70-80% thanks to a government subsidy. The scheme provides flexibility in scheduling work hours. In particular, workers are allowed to block their work hours within the agreed period. For example, a male worker who agrees to reduce his work hours by 50% can choose to work full time during the first 2.5 years of the program and effectively retire at age 57.5.

2.2 The 2000 and 2003 Pension Reforms

To improve the fiscal health of the public pension system, the Austrian government implemented two major pension reforms in 2000 and 2003. Table 1 provides a summary of the changes that were implemented with each reform. The most important change in both reforms was a step-wise increase in the eligibility age for an early retirement pension. The 2000 pension reform was debated in Parliament in June 2000 and enacted by the Austrian government on October 1st of the same year. The reform increased in the eligibility age for an early retirement pension by 1.5 years. The increase was phased-in gradually over time. More specifically, each quarter of birth the eligibility age was raised by 2 months for men born after September 1940 and women born after September 1945 until reaching 61.5 for men born after September 1942 and 56.5 for women born after September 1947. Men with at least 45 insurance years and women with at least 40 insurance years were unaffected by the increase in the eligibility age. In 2000, around 12% of 60-61.5 year old men and 9% of 55-56.5 year old women satisfied this criterion.

Table 1.

Summary of the 2000 and 2003 pension reforms

| Changes | 2000 pension reform | 2003 pension reform |

|---|---|---|

| early retirement age | Step-wise increase in eligibility age for early retirement pension from 55 to 56.5 for women and from 60 to 61.5 for men; exempted if long work history. | Step-wise increase in eligibility age for early retirement pension from 55 to 56.5 for women and from 61.5 to 65 for men; exempted if long work history; corridor pension allows for claiming benefits at 62. |

| other changes | Increased penalties for claiming benefits prior to the NRA from 2 to 3 percent per year (capped at 10.5 percent). | Reduction in the percentage of assessment basis that is replaced by 1 insurance year from 2 to 1.78 percent; increase in penalty for claiming benefits prior to the NRA. |

| Temporary extension of UI benefits from 1 to 1.5 years for certain birth cohorts if 15 employment years in past 25 years. | Increase in the assessment basis from best 15 to best 40 earnings years; phased in 2004-2028. |

Source: Austrian federal laws (Bundesgesetzblätter) no. 92/2000, 71/2003.

Along with this change, the Austrian government temporarily extended the maximum duration of unemployment benefits from 1 to 1.5 years for a subset of individuals. Eligibility was restricted to unemployed men and women with at least 15 employment years in the past 25 years who were born in a certain year. More specifically, in 2000 men born in 1940 and women born in 1945 were eligible, in 2001 men born in 1940-1941 and women born in 1945-1946 were eligible, and in 2002 men born in 1940-1942 and women born in 1945-1947 were eligible. The benefit extension was in effect until December 2002. The reform also increased the penalties for claiming retirement benefits before the NRA and the bonus for claiming after the NRA. Specifically, before the reform, each year of claiming retirement benefits prior to the NRA reduced the pension coefficient by 2 percentage points. After the reform, this number was increased to 3 percentage points.

In June 2003 the Austrian government enacted the 2003 pension reform, which became effective on January 1, 2004. The reform continued the increase in the eligibility age for early retirement pensions from 61.5 to 65 for men and from 56.5 to 60 for women. This increase was phased-in gradually and occurred in two main stages. Each quarter of birth the eligibility age increased by two months for men born between January and June 1943 and women born between January and June 1948, followed by one-month increments per quarter of birth for men born between July 1943 and December 1952 and women born between July 1948 and December 1957. As for the 2000 pension reform, men with at least 45 insurance years and women with at least 40 insurance years were unaffected by the increase in the eligibility age for an early retirement pension.

The reform also reduced the generosity of benefits by lowering the pension coefficient and increasing the penalty for claiming a pension prior to the NRA. Specifically, before the reform each insurance year replaced 2% of the assessment basis. After the reform this number was lowered to 1.88%. Moreover, the reform changed the assessment basis from the best 15 years to the best 40 years. This extension is being phased-in between 2004 and 2028. Unlike the 2000 pension reform, there was no temporary extension of unemployment benefits.

Because the 2003 pension reform eliminated the possibility to claim retirement benefits prior to the NRA, the Austrian government introduced the “corridor pension” on January 1, 2005. This pension is comparable to an early retirement pension and can be claimed between the ages of 62 and 65, conditional on having 37.5 insurance years. Thus, it essentially allows early retirement at age 62, even when the eligibility age for an early retirement pension is higher. Since the female NRA will be gradually increased from 60 to 65 beginning of 2024, for women the corridor pension will only be relevant after 2028. Until then, women can still claim an old age pension prior to age 62.

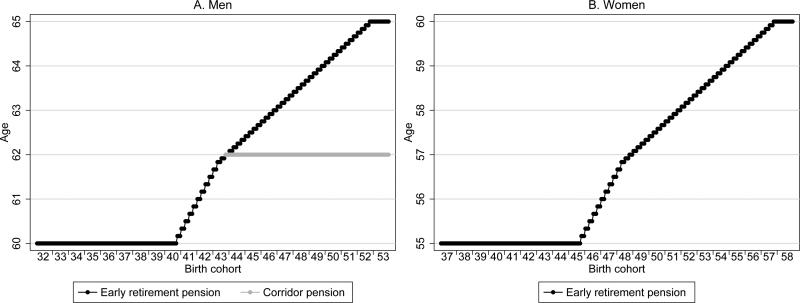

Figure 1 displays the ERA for the birth cohorts used in our subsequent analysis. For men born in September 1940 to September 1947 and for women born in September 1945 to September 1952 the eligibility age for an early retirement pension was increased between 2001 and 2010, which is the last year covered by our data. Over this time period the ERA for women was raised by 3.25 years. The increase in the ERA for men was raised by 2 years due to the introduction of the corridor pension. As Figure illustrates 1, for older birth cohorts the eligibility age for an early retirement pension was increased in two-month increments, followed by one-month increments for younger birth cohorts.

Figure 1.

Increase in the minimum retirement age by gender.

Notes: This figure displays all birth cohorts that are used in our subsequent analysis. The 2000 and 2003 pension reforms implemented an increase in the eligibility age for an early retirement pension to age 65 for men (effective at birth cohort 10/1952) and age 60 for women (effective at birth cohort 10/1957). Since 2005 possibility to claim a corridor pension at age 62. Source: Austrian federal laws (Bundesgesetzblätter) no. 92/2000, 71/2003.

3 Data and Descriptives

3.1 The Austrian Social Security Database

To examine the impact of the increase in the ERA on labor market behavior, we use data from the Austrian Social Security Database (ASSD), which is described in Zweimüller et al. (2009). The data contain very detailed longitudinal information dating back to 1972 for all private sector workers in Austria. For all individuals who claim a public pension by the end of 2008, information on insurance relevant states is available for the years prior to 1972.8 At the individual level the data include gender, nationality, month and year of birth, blue-collar or white-collar status, labor market history, earnings and individual identifiers. The data contain several firm-specific variables: geographical location, industry affiliation and firm identifiers (from 1972 onward) that allow us to link both individuals and firms.

Our main sample consists of all men aged 57-64 with less than 45 insurance years and women aged 52-59 with less than 40 insurance years over the period 1997 to 2010 (men born in January 1932 to December 1953 and women born in January 1937 to December 1958). The sample restrictions are as follows. From the initial sample of 582,006 men and 597,084 women, we exclude 12,955 men and 8,260 women who have worked in publicly-owned industries (public administration, public transportation, and education), as public sector workers are covered by a separate pension system with different eligibility rules. We also exclude 49,305 men and 39,546 women who have spent any time working in jobs defined as heavy labor, as they might be eligible for a special heavy labor pension. We also exclude 79,209 men with more than 45 insurance years and 53,564 women with more than 40 insurance years, as they are not affected by the increase in the ERA. The final sample thus comprises 440,537 men (8,731,826 person-quarter observations) and 495,714 women (9,391,883 person-quarter observations).

Individuals are observed on the 1st of January, April, July, and October in each year. Due to the phase-in of the 2000 and 2003 policy changes, the age at which someone becomes eligible for retirement benefits is a function of the month and year of birth. Since this information is contained in the data, we can determine exactly who is eligible for retirement benefits in a given quarter. The earliest start date for retirement benefits is the first of the month after reaching the ERA. For example, an individual who reaches the ERA in September can start claiming retirement benefits on October 1.

Table 2 presents summary statistics for men aged 57-64 and women aged 52-59 in 2000 (the year before the ERA increase was implemented) and 2010 (the last year in our data). As shown in Panel A, from 2000 to 2010 there have been significant changes in the fraction of men and women in different labor market states. Over this time period the share of individuals claiming retirement benefits decreased from 24.5 to 11.2% among men and from 37 to 7.2% among women. This decline was accompanied by a significant rise in employment from 19.8 to 38.8% among men and from 39.5 to 64.9% among women. However, there is also a slight increase in registered unemployment of 1.1-1.3 percentage points and an increase in the share of individuals in the residual category of roughly 2.5 percentage points.9 The residual category comprises individuals who are neither employed, registered as unemployed, receiving DI benefits, nor receiving retirement benefits. Most individuals in the residual category either receive sickness benefits (around 30%) or survivor benefits (around 15%). Over the same period disability enrollment remained roughly constant among women and declined among men, perhaps reflecting the impact of the reduction in the generosity of disability and retirement benefits that was part of the 2000 and 2003 policy reforms. The share of individuals in the partial retirement program is very low and has increased by only 0.2 percentage points from 2000 to 2010.

Table 7.

Fiscal costs and benefits of ERA increase

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δretirement benefits received (1) | Δtaxes paid (2) | ΔUI benefits received (3) | ΔDI benefits received (4) | Δretirement benefits received (5) | Δtaxes paid (6) | ΔUI benefits received (7) | ΔDI benefits received (8) | |

| pre-ERA | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA-2) | −236*** (54) | −30 (34) | 139** (66) | −102*** (35) | −58*** (19) | −16* (9) | ||

| I(age<ERA-1.5) | −117** (47) | −165*** (23) | 63* (34) | −28 (34) | −167*** (14) | −13 (9) | ||

| I(age<ERA-l) | −96** (48) | −246*** (34) | 46 (38) | −25 (35) | −254*** (26) | 3 (10) | ||

| I(age<ERA-0.5) | −157*** (56) | −205*** (27) | 104** (42) | −55 (36) | −228*** (24) | 4 (10) | ||

| I(age<ERA) | −4,915*** (123) | 1,787*** (86) | 1,891*** (76) | 233*** (37) | −3,333*** (154) | 1,269*** (62) | 1,186*** (81) | 21** (9) |

| post-ERA | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA+0.5) | −810*** (74) | 375*** (50) | 108*** (33) | 147*** (43) | −699*** (26) | 356*** (30) | 97*** (19) | 15 (11) |

| I(age<ERA+l) | −305*** (61) | 6 (58) | 61** (26) | 121*** (40) | −428*** (28) | 172*** (27) | 92*** (18) | 11 (9) |

| I(age<ERA+1.5) | −200*** (60) | −5 (46) | 66*** (23) | 54 (33) | −288*** (42) | 115*** (30) | 84*** (17) | −9 (10) |

| I(age<ERA+2) | −55 (40) | −103** (48) | 23 (14) | 27 (34) | −238*** (24) | 8 (29) | 119*** (15) | −20 (14) |

| R2 | 0.362 | 0.452 | 0.088 | 0.236 | 0.522 | 0.561 | 0.059 | 0.120 |

| #Obs. | 8,731,826 | 8,731,826 | 8,731,826 | 8,731,826 | 9,391,883 | 9,391,883 | 9,391,883 | 9,391,883 |

| #Individuals | 440,537 | 440,537 | 440,537 | 440,537 | 495,714 | 495,714 | 495,714 | 495,714 |

Notes: This table displays the impact of the ERA increase on retirement benefits received, taxes paid, UI benefits received, and DI benefits received. The estimates are based on equation (1) when we include indicator variables for whether an individual's age is below ERA-2 years, ERA-1.5 years, ERA-1 year, ERA-0.5 years, ERA, ERA+0.5 years, ERA+1 year, ERA+1.5 years, and ERA+2 years. In columns (1) and (5) we only include the indicators ERA, ERA+0.5 years, ERA+1 year, ERA+1.5 years, and ERA+2 years because individuals only become eligible for retirement benefits at the ERA. Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the year-quarter of birth. Coefficient and standard errors are multiplied by 100 and should be interpreted as percentage points. Controls in all specifications include dummies for age in months, dummies for year-quarter, experience in last 15 years, blue-collar status, number of insurance years, annual earnings, average earnings in best 15 years, expected UI benefits, dummies for weeks of UI eligibility (20, 30, 39, 52, 78 weeks), expected retirement benefits, number of sick leave days between ages 45-49 for women and ages 50-54 for men, dummies for industry, dummies for birth cohort at a quarterly frequency, dummies for birth cohort interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time, and dummies for age in months interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time. The time period is 1997-2010. Significance levels:

1%

5%

10%.

Panel B shows the characteristics of our sample in 2000 and 2010. For both men and women there are only minor differences in observable characteristics between these two years. There is a slight decline in the mean age for women of 6 months. There is also a decline (increase) in work experience of 5 months (6 months) for men (women). However, the average number of insurance years, which together with age determines eligibility for retirement benefits, remains unchanged between 2000 and 2010. Women are less likely to work in blue-collar occupations and tend to have less sick leave days than men. They also tend to have less insurance years than their male counterparts. These differences largely arise because women in our sample are on average five years younger than men. The next two rows of Panel B show that annual and average earnings of women are roughly one third below annual and average earnings of men.

3.2 Trends by age group

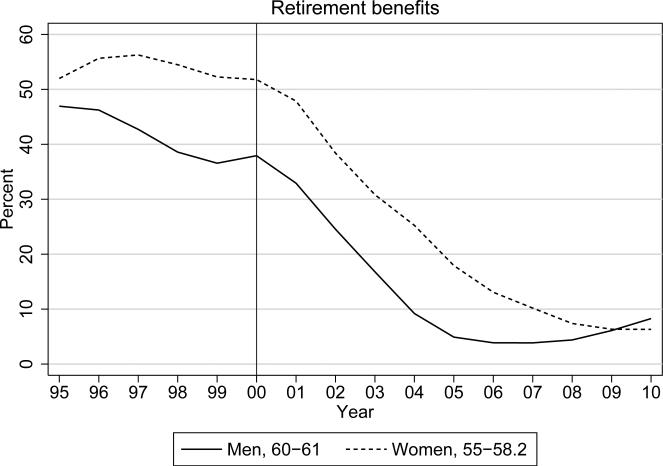

Figure 2 plots trends in claiming of retirement benefits over time among men aged 60-61 with less than 45 insurance years and among women aged 55-58.2 with less than 40 insurance years. For these age groups the ERA was increased between 2001 and 2010. The figure shows that in the year before the 2000 reform became effective, approximately 38% of men aged 60-61 and 52% of women aged 55-58.2 claim retirement benefits. The fraction is higher among women because a large fraction of men exit the labor market before age 60 by claiming a disability pension. After 2000 the fraction of 60-61 year old men claiming retirement benefits decreases by around 33 percentage points up to 2005 and then stays fairly constant. In 2005 the corridor pension was introduced, which allows men to permanently retire at age 62. Similarly, between 2000 and 2010 there is a 45 percentage point decline in the share of 55-58.2 year old women claiming retirement benefits. These drops reflect a mechanical effect of the 2000 and 2003 reforms because men with less than 45 insurance years and women with less than 40 insurance years now have to wait until the new ERA before they can claim retirement benefits.

Figure 2.

Trends in claiming of retirement benefits over time among men aged 60-61 and women aged 55-58.2.

Source: Own calculations, based on Austrian Social Security Data.

However, the figure shows that in 2010 a small share of 60-61 year old men with less than 45 insurance years and 55-58.2 year old women with less than 40 insurance years still claim retirement benefits prior to the new ERA of 62 for men and 58.2 for women. The number of insurance years is not directly observable in the data but is calculated by us based on observed labor market histories. This calculation is prone to measurement error because for some individuals the labor market history is censored at 1972 (as discussed in footnote 8) and what counts as an insurance year is ambiguous in some cases. As a consequence, there are some men (women) in our sample who have more than 45 (40) insurance years, even though according to our calculation they have less than 45 (40) insurance years. These individuals can still claim retirement benefits at the pre-reform ERA of 60 (55).

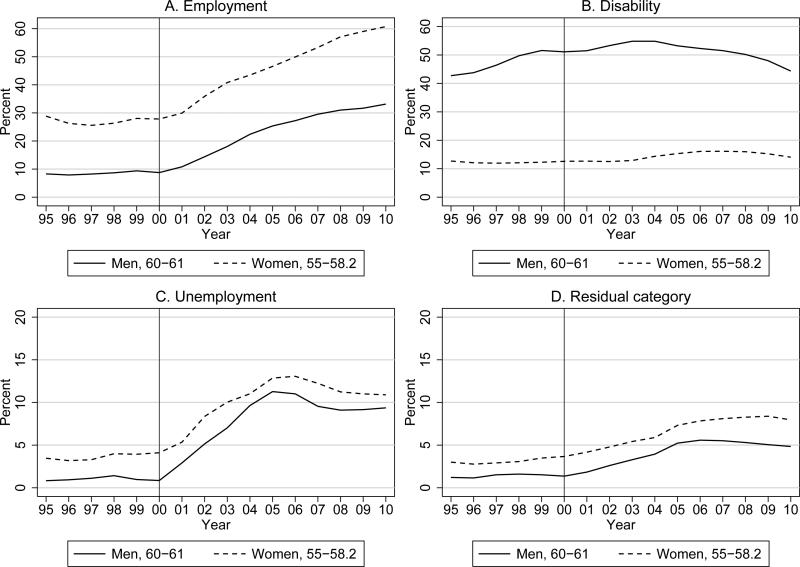

To graphically illustrate the labor supply response among individuals affected by the ERA increase, Figure 3 displays trends in employment, disability, unemployment, and the residual category over time among men aged 60-61 with less than 45 insurance years and women aged 55-58.2 with less than 40 insurance years. As Panel A illustrates, employment rates are relatively constant over time among men and women prior to the ERA reforms. In the years following the 2000 reform, employment rates begin to increase up to 2010 by roughly 20 percentage points among men and 30 percentage points among women, suggesting that the ERA increase had a positive effect on employment.10 Panel B suggest that the increase in the ERA has little effect on DI claims. More specifically, until 2003 the fraction of women on DI stays fairly constant at roughly 12% and then increases slightly by around 4 percentage points. Among men there is an upward trend in disability enrollment that already starts prior to the ERA reforms. After 2004 DI claims begin to decline from around 55% to 45% in 2010. The large difference in the fraction of men and women receiving DI benefits is due to DI benefit rules. Because access to DI benefits is relaxed at age 57, only men have relaxed access to DI benefits prior to the ERA. As illustrated in Panel C, in the years prior to 2000, the unemployment rate among 60-61 year old men and 55-58.2 year old women is constant over time at a very low level. After the first ERA reform in 2000 the unemployment rate among men and women begins to increase by almost 10 percentage points up to 2005 and then stays fairly constant at the new level. Finally, Panel D shows that there is an increase in the fraction of individuals in the residual category after the ERA reforms become effective, although the increase is much smaller (roughly 4 percentage points) compared to the changes in employment and unemployment.

Figure 3.

Trends in employment, unemployment, disability, and the residual category over time among men aged 60-61 and women aged 55-58.2.

Source: Own calculations, based on Austrian Social Security Data.

3.3 Trends by birth cohort

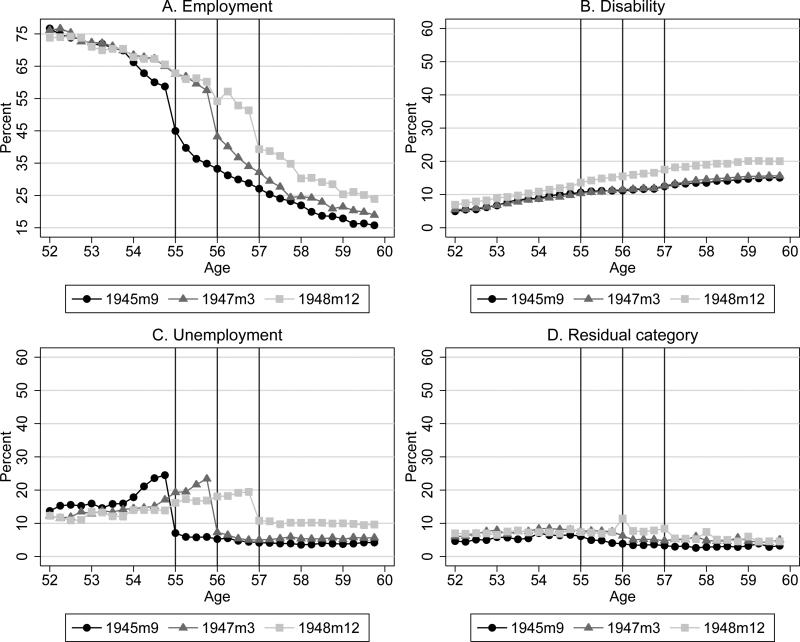

The trends in Figure 3 strongly suggest that the ERA reforms have important effects on labor supply behavior. However, there is also the possibility that part of the documented trends could simply reflect the impact of factors other than the ERA reforms such as changes in macroeconomic conditions. To get a more precise impression of the ERA increase's impact on labor supply, Figure 4 displays the percent of 57 to 64 year old men in employment, disability, unemployment, and the residual category for different birth cohorts. The vertical lines represent the cohort-specific ERA as implemented by the 2000 and 2003 policy changes.

Figure 4.

Trends in employment, disability, unemployment, and the residual category over age for men born in different months.

Source: Own calculations, based on Austrian Social Security Data.

As shown in Panel A, there is a drop in employment of roughly 10 percentage points at the ERA. However, for younger birth cohorts the decline in employment occurs later in life due to the increase in the ERA. This suggests that a significant fraction of workers stays in employment for one additional year if the ERA is increased by one year. Panel B suggests that the ERA reforms have little effect on DI claims given that DI enrollment varies only gradually across birth cohorts. As Panel C illustrates, the fraction of men registered as unemployed drops significantly at the ERA, but because younger birth cohorts have a higher ERA they tend to stay unemployed longer than older birth cohorts. Interestingly, unemployment begins to rise as a cohort approaches its ERA, indicating that the UI program serves as a bridge to retirement benefits for some individuals. Finally, Panel D shows that the share of men in the residual category varies little across different birth cohorts.

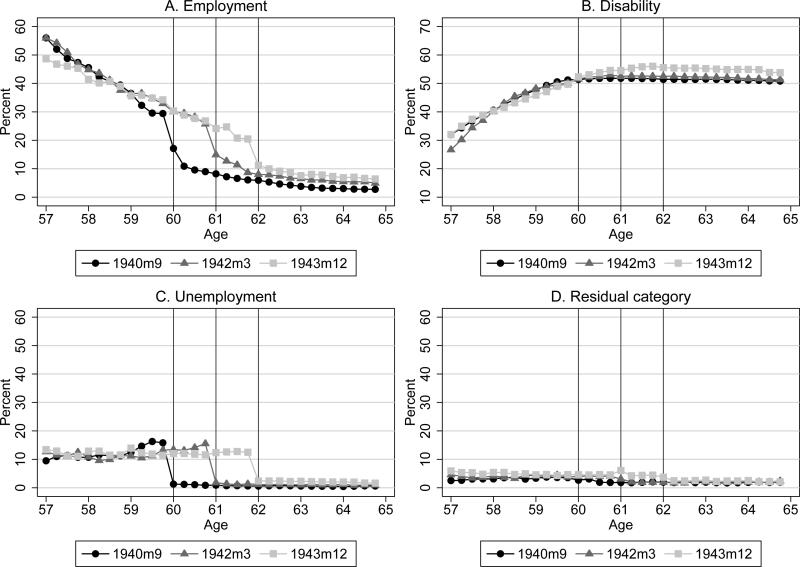

Figure 5 presents trends in employment, disability, unemployment, and the residual category for women between the ages 52 and 59 by birth cohort. As shown in Panel A, a significant share of women responds to the ERA increase by delaying job exit given that for younger birth cohorts the drop in employment occurs at a later age. For younger birth cohorts employment rates are also higher after the ERA, suggesting that the policy changes may affect job exits beyond the ERA. Panel B suggests that the ERA reforms have little impact on the probability of receiving DI benefits. However, Panel C illustrates that increasing the ERA leads to a significant increase in registered unemployment. In particular, due to the increase in the ERA younger birth cohorts tend to stay longer in unemployment than older birth cohorts. As for men, there is evidence that the UI program serves as a bridge to retirement benefits given that the unemployment rate begins to increase the closer a birth cohort gets to its ERA. Finally, Panel D suggests that the ERA reforms have only little impact on the fraction of women in the residual category. These figures are consistent with the hypothesis that a rise in the ERA increases employment among men and women, but has also important spillover effects into other social insurance programs, primarily the UI program. In the next section, we describe our identification strategy to quantify the magnitudes of these effects empirically.

Figure 5.

Trends in employment, disability, unemployment, and the residual category over age for women born in different months.

Source: Own calculations, based on Austrian Social Security Data.

4 Identification Strategy

The goal of the 2000 and 2003 reforms was to foster employment among older workers by increasing the ERA. While the possibility to claim retirement benefits was abolished for certain age groups as a result of this increase, eligibility criteria for UI benefits, and DI benefits remained the same. Therefore, it is plausible that some individuals who would have otherwise claimed retirement benefits responded to this change by seeking benefits from other social insurance programs. Such a change in behavior could occur already before the ERA if individuals were sufficiently forward-looking and recognized that their ERA has increased. Such spillover effects into other social insurance programs would diminish the positive effect of these reforms on employment.

Because the increase in the ERA was phased-in gradually, the age at which an individual could claim retirement benefits depended on the month of birth. For example, men born before October 1940 could claim benefits at age 60 while those born in October to December 1940 had to wait 2 months longer before they became eligible for benefits. As illustrated in Figure 1, there are similar discontinuities in the ERA for other birth cohorts and for women. On this basis, the primary approach to estimate the effect of the increase in the ERA is to compare the labor market behavior of younger birth cohorts to older birth cohorts who were not affected by the increase in the ERA.

This comparison can be implemented by estimating regressions of the following type:

| (1) |

where i denotes individual, t quarter, and yit is the outcome variable of interest (e.g., when examining employment effects, yit represents an indicator for whether the individual is employed); θi are age-in-months fixed effects to control for age-specific levels in labor market behavior; λt are year-quarter fixed effects to capture common time shocks in labor market behavior; and Xit represents individual or region specific characteristics to control for any observable differences that might confound the analysis. Equation (1) is estimated separately for men aged 57-64 and women aged 52-59 using data for the period 1997 to 2010. The key explanatory variable is I(age < ERA), which is equal to one if an individual's age in quarter t is below the ERA, and zero otherwise. This indicator varies over time and across age groups due to the ERA increase. For example, in 2000 I(age < ERA) is equal to one for all men below age 60 and all women below age 55. In the first quarter of 2001 I(age < ERA) is equal to one for men below age 60 and 2 months and women below age 55 and 2 months because the first two-month increase in the ERA became effective on January 1, 2001.

The identifying assumption is that, absent the increase in the ERA, the change in yit would have been comparable between age groups not yet eligible for retirement benefits (treatment group) and those eligible (comparison group) after controlling for background characteristics. Under this assumption, γ measures the average causal effect of an increase in the ERA on yit, using variation over time.

A potential concern of our estimation approach is that trends in labor supply behavior could be changing across age groups over time for reasons unrelated to the ERA increase. Figure 3 shows that these pre-existing trends were particularly apparent for DI enrollment among men and, to a lesser extent, for employment among women, perhaps driven by a general increase in female labor force participation. We run a placebo test to examine the extent to which the dummy I(age < ERA) is picking up spurious trends. More specifically, we estimate equation (1) for the period 1987 to 2000 assuming that the increase in the ERA started in the first quarter of 1991; during this time period the ERA remained effectively unchanged, and so we expect γ to be zero.

The 2000 and 2003 pension reforms implemented other changes to the pension system, in addition to the increase in the ERA. These changes may also have affected labor supply behavior across age groups differently, which would violate the identifying assumption. In particular, both the 2000 and 2003 pension reforms raised the penalty for claiming retirement benefits before the NRA, but the implied reductions in retirement benefits were relatively modest. For example, the 2000 pension reform reduced retirement benefits of 62 year old men by 3 percentage points. The penalty implemented with the 2003 reform was even smaller. Hence, the impact of the increased penalties on labor supply behavior is likely to be small. To account for the changes in benefit generosity, we control for the expected retirement benefits that an individual would receive if he or she claimed in quarter t. This variable captures the changes in retirement benefits implied by the reforms.

The 2000 pension reform also temporarily extended the duration of unemployment benefits from 1 to 1.5 years for certain groups until December 2002. The extension was limited to a small group of people; only men born in 1940-1942 and women born in 1945-1947 with at least 15 employment years in the past 25 years were eligible. This extension potentially affects the employment response of the ERA reforms if eligible individuals responded to the increase in the ERA by seeking UI benefits instead of remaining in employment. In equation (1) we control for the temporary extension in UI benefits by including a dummy that is equal to 1 if an individual is eligible for the extension in quarter t and 0 otherwise.11

5 Empirical results

5.1 Main effects

Table 3 present OLS estimates of the impact of the policy change on the claiming of retirement benefits, employment, unemployment, disability, and the residual category. The dependent variable yit is a dummy, which is equal to 1 if an individual is in the state in question and 0 otherwise. Columns 1 through 4 provide estimates of our key explanatory variable I(age < ERA) for men and columns 5 through 8 display analogous results for women.

Table 3.

Main effects

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| A. Retirement benefits | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA) | −26.34*** (0.61) | −24.85*** (0.46) | −21.12*** (0.93) | 1.03*** (0.22) | −34.45*** (1.04) | −24.63*** (0.94) | −22.06***(1.13) | 0.19 (0.28) |

| R2 | 0.248 | 0.345 | 0.275 | 0.433 | 0.369 | 0.492 | 0.420 | 0.442 |

| Pre-policy mean | 37.93 | 37.93 | 37.93 | 49.82 | 52.09 | 52.09 | 52.09 | 52.61 |

| B. Employment | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA) | 12.09*** (0.45) | 9.75*** (0.30) | 7.50*** (0.47) | −0.17 (0.17) | 18.91*** (0.50) | 11.00*** (0.34) | 9.26*** (0.38) | −0.03 (0.12) |

| R2 | 0.196 | 0.385 | 0.300 | 0.355 | 0.225 | 0.410 | 0.331 | 0.342 |

| Pre-policy mean | 8.76 | 8.76 | 8.76 | 9.66 | 27.56 | 27.56 | 27.56 | 26.02 |

| C. Unemployment | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA) | 10.64*** (0.28) | 12.51*** (0.31) | 11.81*** (0.53) | −0.66*** (0.19) | 11.79*** (0.52) | 11.77*** (0.65) | 11.50*** (0.76) | −0.14 (0.22) |

| R2 | 0.045 | 0.108 | 0.097 | 0.128 | 0.025 | 0.086 | 0.077 | 0.119 |

| Pre-policy mean | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 4.07 | 4.07 | 4.07 | 4.28 |

| D. Disability | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA) | 1.90*** (0.65) | 1.01*** (0.16) | 0.66*** (0.12) | −0.19** (0.09) | 0.84*** (0.23) | 0.14*** (0.05) | 0.12*** (0.04) | −0.02 (0.04) |

| R2 | 0.025 | 0.293 | 0.292 | 0.273 | 0.012 | 0.156 | 0.156 | 0.161 |

| Pre-policy mean | 51.10 | 51.10 | 51.10 | 38.24 | 12.64 | 12.64 | 12.64 | 13.28 |

| E. Residual category | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA) | 1.71*** (0.09) | 1.58*** (0.09) | 1.14*** (0.10) | −0.01 (0.03) | 2.91*** (0.09) | 1.71*** (0.10) | 1.18*** (0.11) | −0.00 (0.03) |

| R2 | 0.009 | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.031 | 0.009 | 0.095 | 0.112 | 0.075 |

| Pre-policy mean | 1.36 | 1.36 | 1.36 | 1.56 | 3.65 | 3.65 | 3.65 | 3.81 |

| Controls | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Age range | 57-64 | 57-64 | 60-62.5 | 57-64 | 52-59 | 52-59 | 55-58.5 | 52-59 |

| Years | 1997-2010 | 1997-2010 | 1997-2010 | 1987-2000 | 1997-2010 | 1997-2010 | 1997-2010 | 1987-2000 |

| #Obs. | 8,731,826 | 8,731,826 | 2,796,527 | 8,441,943 | 9,391,883 | 9,391,883 | 4,199,444 | 8,275,754 |

| #Individuals | 440,537 | 440,537 | 318,272 | 422,068 | 495,714 | 495,714 | 378,103 | 402,520 |

Notes: This table displays estimates of equation (1). Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the year-quarter of birth. Coefficient and standard errors are multiplied by 100 and should be interpreted as percentage points. All regressions include dummies for age in months and dummies for year-quarter. Additional controls in columns (2)-(4) and (6)-(8) are experience in last 15 years, blue-collar status, number of insurance years, annual earnings, average earnings in best 15 years, expected UI benefits, dummies for weeks of UI eligibility (20, 30, 39, 52, 78 weeks), expected retirement benefits, number of sick leave days benefits between ages 45-49 for women and ages 50-54 for men, dummies for industry, dummies for birth cohort at a quarterly frequency, dummies for birth cohort interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time, and dummies for age in months interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time. Reported pre-policy means are for men aged 60-61 and women aged 55-58.2 in 2000 (1990 in columns (4) and (8)). Significance levels:

1%

5%

*10%.

Column 1 of Table 3 reports the labor supply responses to the increase in the ERA from a specification that only includes dummies for age in months and year-quarter fixed effects. Column 1 of Panel A shows that the ERA reforms reduce retirement benefit claiming among affected men by 26.34 percentage points. This drop reflects a mechanical effect of the ERA reforms because men with less than 45 insurance years are forced to delay their benefit claims until the new ERA. Column 1 of Panel B indicates that the ERA increase is accompanied by a rise in employment of 12.09 percentage points. This increase may seem small, but it is important to realize that many 60-61 year old men were not affected by the ERA reforms – around 50% exited the labor market before reaching the ERA through the DI program and around 10% were already working past the ERA before the reforms. According to Table 3, the maximum employment response is 26.34 percentage points if all men who delay claiming continued to work. Viewed in this way the employment response is quite substantial because roughly 45% of men who delay claiming continue to work. Nonetheless, the estimated employment response in Table 3 is much smaller than one would expect from an inspection of Panel A in Figure 3. Part of the reason for the difference between the regression estimate and the graphical evidence is that during the 2000s employment rates were also rising among men in the comparison group (i.e. those who were not affected by the ERA reforms). Column 1 of Panel C shows that there is also an increase in registered unemployment of 10.64 percentage points. On the other hand, the increase in the ERA has little impact on DI enrollment, as illustrated in column 1 of Panel D. Finally, column 1 of Panel E indicates that there is also an increase in the share of men in the residual category, but the increase is quantitatively small compared to the increase in employment and unemployment.

The specification summarized in column 2 adds additional control variables to equation (1). Controlling for other variables reduces the employment response by 2.3 percentage points and increases the unemployment response by 1.9 percentage points. Column 3 presents analogous estimates if we restrict the sample to men between ages 60 and 62.5 (as opposed to ages 57 and 64 in column 2). The estimates are quantitatively similar to the estimates for the wider age range in column 2, except for the employment response which is 2.3 percentage points lower. The estimates in columns (1)-(3) will be biased if the treatment and comparison groups have different labor supply tendencies. To shed light on this concern, we estimate the same specification as in column 2 for the period 1987 to 2000 and assume (incorrectly) that the increase in the ERA started in the first quarter of 1991. Column 4 shows that some estimates of this placebo test are statistically significant, but they are all very small in magnitude, suggesting that our estimation strategy is not simply picking up long-run trends in differences across age groups.

Turning to the results for women, column 5 reports estimates of equation (1) for women between ages 52 and 59 over the period 1997 to 2010. In this specification we include age in months fixed effects and year-quarter fixed effects. Column 5 of Panel A demonstrates that the ERA reforms reduce the claiming of retirement benefits among affected women by 34.45 percentage points. As mentioned above, this is a mechanical drop given that women with less than 40 insurance years cannot claim retirement benefits until they have reached the new ERA. Column 5 of Panel B indicates that the ERA reforms increase employment among affected women by 18.91 percentage points. Or put differently, almost 55% (18.91/34.45) of women who delay claiming as a response to the ERA increase continue to work. As for men, there is also a significant increase in registered unemployment of 11.79 percentage points (column 5 of Panel C), but only a very small increase in DI enrollment (column 5 of Panel D). Column 5 of Panel E shows that the ERA reforms also increase the fraction of women in the residual category by 2.91 percentage points.

Column 6 shows that adding additional control variables to (1) reduces the positive effect on employment by 7.9 percentage points. Column 7 illustrates that restricting the age range to women between ages 55 and 58.5 has little impact on the estimates, except for the employment response which is 1.7 percentage points lower. Column 8 presents estimates for our placebo test that incorrectly assumes that the ERA increase started in the first quarter of 1991. All estimates of this specification are small in size and statistically insignificant.

The low disability response is in contrast with Duggan et al. (2007) who find that the increase in the full retirement age in the U.S. significantly increased DI enrollment. Part of the reason that an effect of the Austrian reforms on disability claims is less apparent, is that most workers with poor health have already exited the labor market before reaching the ERA through the DI program. For example, in 2000 before the increase in the ERA was implemented around 50% of 60 and 61 year old men received DI benefits compared to roughly 15% in the U.S. ((Duggan et al., 2007)). Another possible explanation for the low disability response is that applications for DI benefits may be screened more rigorously after the increase in the ERA, even though none of the reforms have changed the formal eligibility criteria for DI benefits. In this case there would be little variation in disability enrollment even though individuals are more likely to seek benefits. Information on applications for DI benefits, regrettably, is not recorded in the data. Thus, it is impossible to examine the reform's impact on applications for DI benefits.

The effects shown in Table 3 can result either from changes in the inflow into a certain state, or changes in the persistence in a certain state, or both. To shed light on the importance of these two effects, Table 4 reports estimates from equation (1) for transitions from and persistence in employment and unemployment. We focus on these two states because they are most affected by the ERA reforms. Column 1 of Panel A suggests that the ERA reforms increase employment persistence by 27.52 percentage points among affected men. The ERA reforms also lead to a small increase in transitions from employment into unemployment (column 2 of Panel A), but have only minor effects on transitions from employment into disability (column 3) or the residual category (column 4). Panel B summarizes the results for transitions from and persistence in unemployment among men. As column 2 of Panel B demonstrates, there is a sizeable increase in unemployment persistence of 80.36 percentage points, while transitions to other exit states are largely unaffected by the increase in the ERA.

Table 4.

Effect on transitions from employment and unemployment by gender

| Status at t: | Employment (1) | Unemployment (2) | Disability (3) | Residual category (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||

| A. Employed at t – 1 | ||||

| I(age<ERA) | 27.52*** (0.78) | 2.21*** (0.13) | 0.49*** (0.12) | −0.90*** (0.16) |

| R2 | 0.095 | 0.038 | 0.019 | 0.025 |

| Pre-policy mean | 70.40 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 2.46 |

| #Obs. | 2,077,166 | |||

| #Individuals | 202,544 | |||

| B. Unemployed at t – 1 | ||||

| I(age<ERA) | 0.72 (0.57) | 80.36*** (1.75) | 0.15 (0.28) | 1.53*** (0.18) |

| R2 | 0.091 | 0.233 | 0.050 | 0.014 |

| Pre-policy mean | 2.39 | 21.58 | 0.92 | 1.63 |

| #Obs. | 557,806 | |||

| #Individuals | 82,880 | |||

| Women | ||||

| C. Employed at t – 1 | ||||

| I(age<ERA) | 11.37*** (0.26) | 0.93*** (0.07) | −0.10** (0.04) | −0.33*** (0.06) |

| R2 | 0.056 | 0.027 | 0.003 | 0.027 |

| Pre-policy mean | 88.10 | 2.21 | 0.87 | 1.92 |

| #Obs. | 4,375,311 | |||

| #Individuals | 325,905 | |||

| D. Unemployed at t – 1 | ||||

| I(age<ERA) | 0.45** (0.20) | 44.36*** (1.95) | −0.15 (0.12) | 1.83*** (0.17) |

| R2 | 0.075 | 0.140 | 0.011 | 0.017 |

| Pre-policy mean | 5.85 | 55.35 | 2.08 | 4.30 |

| #Obs. | 792,910 | |||

| #Individuals | 117,777 | |||

Notes: This table displays estimates of equation (1). Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the year-quarter of birth. Coefficient and standard errors are multiplied by 100 and should be interpreted as percentage points. Controls in all specifications include dummies for age in months, dummies for year-quarter, experience in last 15 years, blue-collar status, number of insurance years, annual earnings, average earnings in best 15 years, expected UI benefits, dummies for weeks of UI eligibility (20, 30, 39, 52, 78 weeks), expected retirement benefits, number of sick leave days between ages 45-49 for women and ages 50-54 for men, dummies for industry, dummies for birth cohort at a quarterly frequency, dummies for birth cohort interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time, and dummies for age in months interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time. The time period is 1997-2010. Reported pre-policy means are for men aged 60-61 and women aged 55-58.2 in 2000. Significance levels:

1%

5%

* = 10%.

The analogous estimates for women are summarized in Panels C and D of Table 4. As for men, there is a sizeable increase in employment persistence among treated women of 11.37 percentage points (column 1 of Panel C). On the other hand, the rise in the ERA has almost no effect on transitions from employment into unemployment, disability claims, or the residual category. The estimates in Panel D illustrate that the ERA reforms lead to a sizeable increase in unemployment persistence of 44.36 percentage points (columns 2), but have only a small impact on transitions from unemployment into employment, disability, or the residual category

5.2 Sensitivity analysis

Previous studies have documented that health (e.g., Rust and Phelan, 1997; Blau and Gilleskie, 2001) and past earnings (e.g. Bound et al., 2010) are important determinants of the retirement decision. To examine how these factors interact with the policy changes, Table 5 reports OLS estimates of equation (1) by health and lifetime earnings. Lifetime earnings here are measured by the average earnings of the best 15 years. Health is measured by the number of days spent in sick leave between ages 45 and 49 for women and between ages 50 and 54 for men. An individual is considered “healthy” if the number of days spent on sick leave is below the 75th percentile in the distribution of sick leave days. Individuals with sick leave days above the 75th percentile are defined as “unhealthy”.

Table 5.

Estimates by health status and by median of life-time earnings

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy |

Unhealthy |

Healthy |

Unhealthy |

|||||

| earnings < median (1) | earnings ≥ median (2) | earnings < median (3) | earnings ≥ median (4) | earnings < median (5) | earnings ≥ median (6) | earnings < median (7) | earnings ≥ median (8) | |

| A. Employment | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA) | 10.12*** (0.35) | 15.82*** (0.53) | 1.96*** (0.26) | 2.79*** (0.21) | 9.27*** (0.34) | 16.92*** (0.70) | 5.47*** (0.29) | 9.24*** (0.40) |

| R2 | 0.341 | 0.463 | 0.146 | 0.209 | 0.365 | 0.472 | 0.297 | 0.350 |

| Pre-policy mean | 7.77 | 14.50 | 1.86 | 1.35 | 33.20 | 29.29 | 16.27 | 16.44 |

| B. Unemployment | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA) | 11.13*** (0.29) | 16.59*** (0.52) | 7.45*** (0.32) | 8.21*** (0.38) | 8.68*** (0.62) | 11.22*** (0.66) | 13.27*** (0.90) | 18.48*** (0.84) |

| R2 | 0.097 | 0.141 | 0.143 | 0.114 | 0.052 | 0.080 | 0.114 | 0.127 |

| Pre-policy mean | 1.46 | 0.30 | 1.28 | 0.24 | 5.44 | 1.91 | 7.30 | 3.24 |

| C. Disability | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA) | 1.30*** (0.26) | 1.33*** (0.17) | 0.93*** (0.21) | 0.95*** (0.23) | −0.07 (0.13) | 0.11 (0.08) | 0.27 (0.22) | 0.38** (0.18) |

| R2 | 0.202 | 0.241 | 0.172 | 0.237 | 0.064 | 0.075 | 0.149 | 0.211 |

| Pre-policy mean | 52.16 | 29.21 | 83.34 | 81.61 | 10.65 | 6.27 | 27.33 | 23.32 |

| #Obs. | 3,282,201 | 3,282,629 | 1,083,339 | 1,083,657 | 3,566,938 | 3,567,433 | 1,128,561 | 1,128,951 |

| #Individuals | 176,704 | 169,795 | 58,648 | 57,251 | 203,941 | 196,398 | 62,046 | 60,477 |

Notes: This table displays estimates of equation (1). Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the year-quarter of birth. Coefficient and standard errors are multiplied by 100 and should be interpreted as percentage points. Controls in all specifications include dummies for age in months, dummies for year-quarter, experience in last 15 years, blue-collar status, number of insurance years, annual earnings, average earnings in best 15 years, expected UI benefits, dummies for weeks of UI eligibility (20, 30, 39, 52, 78 weeks), expected retirement benefits, number of sick leave days between ages 45-49 for women and ages 50-54 for men, dummies for industry, dummies for birth cohort at a quarterly frequency, dummies for birth cohort interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time, and dummies for age in months interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time. The time period is 1997-2010. Reported pre-policy means are for men aged 60-61 and women aged 55-58.2 in 2000. Significance levels:

1%

5%

* = 10%.

Interestingly, as shown in columns 1 to 4 of Panel A, the increase in employment is more pronounced for the healthy. Moreover, healthy individuals react more strongly to the ERA increase the higher their lifetime income. The ERA reforms increase employment by 15.82 percentage points among healthy men above the median of the lifetime earnings distribution compared to 10.12 percentage points among those below the median. The income gradient of the ERA effect is flatter among the unhealthy, but also among them the employment response is stronger for high-wage workers.

The situation is similar for women (columns 5 to 8 of Panel A). There is a positive income-gradient of the ERA effects, i.e. high-wage females react more strongly to the ERA increase than low-wage females. The employment response is weaker among unhealthy women compared to healthy women although the difference is less pronounced than for men. The smaller difference between healthy and unhealthy women relative to men is attributable to disability pension rules. Because access to DI benefits is relaxed at age 57, only men but not women have relaxed access to DI benefits prior to the ERA. As a consequence, many less healthy males leave the labor force before reaching the ERA by claiming DI benefits, while many less healthy females do not because relaxed DI benefits are not yet available to them.

Panel B of Table 5 indicates that there is also substantial heterogeneity in the unemployment response among subgroups of the population. While for healthy men the unemployment response is quantitatively similar to the employment effect, for unhealthy men the impact on registered unemployment is roughly three times larger than the employment response. Similarly, among women the ratio of unemployment to employment is roughly twice as large for the unhealthy relative to the healthy. The impact of the ERA reforms on DI claims is very similar for the different subgroups of the population, as shown in Panel C of Table 5. However, there are large differences in the baseline level of individuals receiving DI benefits across subgroups, particularly among men. For example, roughly 80% of unhealthy men with life-time earnings above the median exit the labor market by claiming DI benefits compared to only 29% among healthy men with life-time earnings above the median. The patterns are similar for women and for men with life-time earnings below the median, although the differences between the healthy and the unhealthy are less pronounced.

These findings suggest that the less healthy, low-wage workers are to some extent protected by the potential negative effects of the ERA increase because they mostly rely on other government programs, in particular the UI and DI programs, while healthy, high-wage workers respond to the ERA reforms by working longer until they reach the new ERA. The prolonged employment of healthy, high-wage workers also generates additional tax revenues for the government (in addition to savings in retirement benefit payments). However, these additional revenues come at the cost of less leisure time among healthy, high-wage workers.

Forward-looking individuals who realize that the ERA is higher may adjust their labor supply behavior already before reaching the ERA. Similarly, an increase in the ERA may also affect labor supply and claiming behavior above the ERA. To examine labor supply responses pre- and post-ERA, we augment equation (1) with a series of indicator variables for intervals before and after an individual's ERA. Specifically, we include indicators for whether an individual's age is below ERA-2 years, ERA-1.5 years, ERA-1 year, ERA, ERA-0.5 years, ERA+0.5 years, ERA+1 year, ERA+1.5 years, and ERA+2 years.12 Each coefficient measures the change in the outcome variable in a given interval relative to the next higher interval. For example, the indicator I(age<ERA+0.5) captures the change in the outcome variable in the interval [ERA, ERA+0.5 years) relative to the following interval [ERA+0.5 years, ERA+1 year).13 Table 6 displays the estimates of this augmented specification.

Table 6.

Effects pre- and post-ERA

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retirement benefits (1) | Employment (2) | Unemployment (3) | Disability (4) | Retirement benefits (5) | Employment (6) | Unemployment (7) | Disability (8) | |

| pre-ERA | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA-2) | −1.08*** (0.28) | −0.24 (0.23) | 0.78** (0.33) | −0.64*** (0.20) | −0.57*** (0.16) | −0.15* (0.08) | ||

| I(age<ERA-1.5) | −0.52** (0.21) | −1.02*** (0.15) | 0.46** (0.18) | 0.06 (0.20) | −1.56*** (0.11) | −0.15** (0.07) | ||

| I(age<ERA-l) | −0.51** (0.23) | −1.51*** (0.22) | 0.50** (0.20) | 0.40* (0.23) | −2.38*** (0.24) | −0.03 (0.08) | ||

| I(age<ERA-0.5) | −0.39 (0.25) | −1.30*** (0.17) | 0.64*** (0.20) | 0.30 (0.24) | −2.19*** (0.21) | −0.04 (0.09) | ||

| I(age<ERA) | −24.77*** (0.56) | 8.98*** (0.38) | 12.18*** (0.42) | 1.35*** (0.21) | −25.43*** (1.03) | 10.88*** (0.41) | 11.46*** (0.72) | 0.08 (0.08) |

| post-ERA | ||||||||

| I(age<ERA+0.5) | −4.14*** (0.37) | 1.25*** (0.24) | 0.71*** (0.21) | 0.90*** (0.22) | −5.31*** (0.20) | 2.27*** (0.21) | 1.03*** (0.18) | 0.07 (0.09) |

| I(age<ERA+l) | −1.51*** (0.31) | −0.36 (0.28) | 0.31* (0.16) | 0.75*** (0.21) | −3.31*** (0.19) | 0.98*** (0.22) | 0.87*** (0.17) | 0.06 (0.07) |

| I(age<ERA+1.5) | −0.96*** (0.29) | −0.31 (0.28) | 0.33** (0.16) | 0.36** (0.16) | −2.23*** (0.28) | 0.47** (0.21) | 0.78*** (0.15) | 0.02 (0.06) |

| I(age<ERA+2) | −0.23 (0.18) | −0.52* (0.27) | 0.10 (0.10) | 0.13 (0.18) | −1.78*** (0.20) | −0.19 (0.25) | 1.10*** (0.14) | 0.07 (0.07) |

| R2 | 0.345 | 0.385 | 0.109 | 0.293 | 0.492 | 0.410 | 0.087 | 0.156 |

| #Obs. | 8,731,826 | 8,731,826 | 8,731,826 | 8,731,826 | 9,391,883 | 9,391,883 | 9,391,883 | 9,391,883 |

| #Individuals | 440,537 | 440,537 | 440,537 | 440,537 | 495,714 | 495,714 | 495,714 | 495,714 |

Notes: This table displays estimates of equation (1) when we include indicator variables for whether an individual's age is below ERA-2 years, ERA-1.5 years, ERA-1 year, ERA-0.5 years, ERA, ERA+0.5 years, ERA+1 year, ERA+1.5 years, and ERA+2 years. In columns (1) and (5) we only include the indicators ERA, ERA+0.5 years, ERA+1 year, ERA+1.5 years, and ERA+2 years because individuals only become eligible for retirement benefits at the ERA. Standard errors, in parentheses, are clustered at the year-quarter of birth. Coefficient and standard errors are multiplied by 100 and should be interpreted as percentage points. Controls in all specifications include dummies for age in months, dummies for year-quarter, experience in last 15 years, blue-collar status, number of insurance years, annual earnings, average earnings in best 15 years, expected UI benefits, dummies for weeks of UI eligibility (20, 30, 39, 52, 78 weeks), expected retirement benefits, number of sick leave days between ages 45-49 for women and ages 50-54 for men, dummies for industry, dummies for birth cohort at a quarterly frequency, dummies for birth cohort interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time, and dummies for age in months interacted with a second-order polynomial in calendar time. The time period is 1997-2010. Significance levels:

1%

5%

10%.

Columns (1) and (5) show that the pension reforms reduce claiming of retirement benefits at the ERA by 24.77 percentage points among men and 25.43 percentage points among women. The post-ERA interaction terms reveal that retirement benefit claims beyond the ERA are also reduced by the reforms, although the effect diminishes the further an individual's age is above the ERA. For example, men and women whose age is in the interval [ERA, ERA+0.5 years) reduce claiming of retirement benefits by 4.14 and 5.31 percentage points, respectively. Columns (2) and (6) suggest that employment rates at ages before and after the ERA do not change significantly with the ERA increase, except for the interval [ERA, ERA+0.5 years) where employment rates increase by 1.25 percentage points among men and 2.27 percentage points among women. As columns (3) and (6) illustrate, unemployment rates in the age intervals pre-ERA are negative and increase in absolute size the closer the interval is to the ERA. Since each indicator measures the change in the outcome variable in a given interval relative to the next higher interval, these effects imply that unemployment increases as a cohort approaches its ERA. This pattern is consistent with the role of the UI program serving as a bridge to retirement benefits for some individuals. Finally, DI benefit claims pre- and post-ERA appear to increase slightly among men (column 4) and are unchanged among women (column 8).

5.3 The fiscal implications of the ERA increase

The primary objective of the 2000 and 2003 pension reforms was to reduce expenditures in the public pension system by fostering labor force participation among older workers. Between 2001 and 2010, the reforms effectively increased the ERA by 2 years among men and by 3.25 years among women. The results of our above empirical analysis suggest that the reforms succeeded in increasing the employment rate. However, there is also evidence for considerable spillover effects to UI benefit claims and, to a lesser extent, to DI benefit claims.

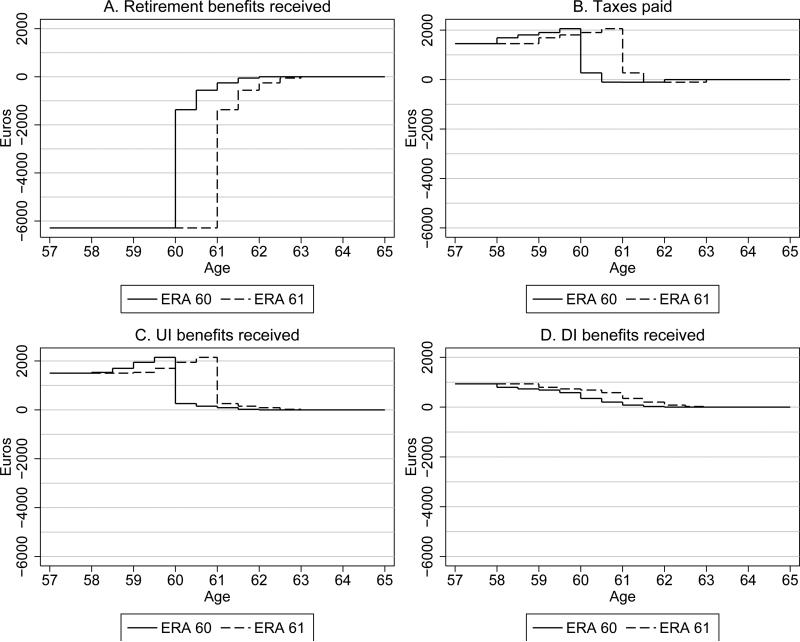

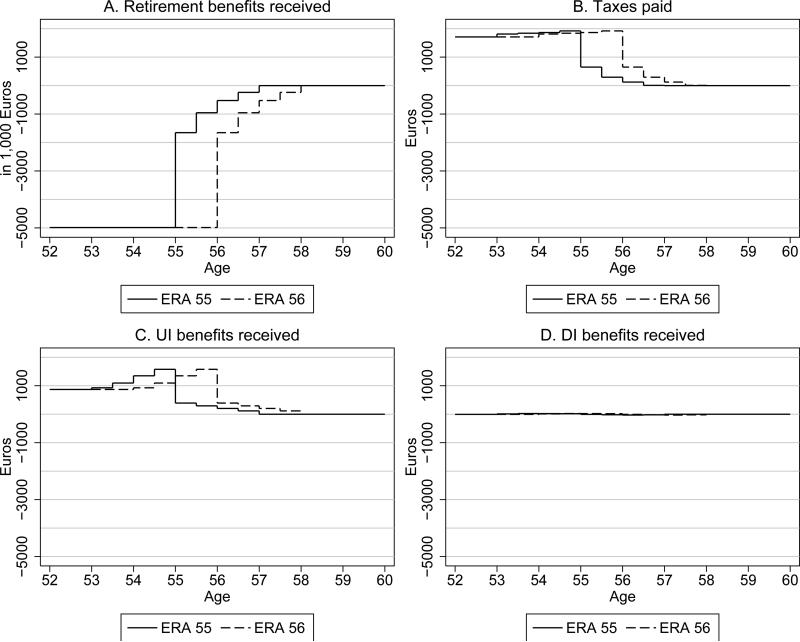

In this section we investigate the fiscal implication of the ERA in more detail. In particular, we estimate the same augmented specification of equation (1) as in the previous section, by including a series of indicator variables for time intervals before and after an individual's ERA. However, in contrast to the previous specification, the dependent variables are no longer labor force states but are benefit receipts (or tax payments) associated with each state. Table 7 shows the results. The dependent variable in the male (female) regressions of columns 1-4 (5-8) are retirement benefits received, taxes paid, UI benefits received, and DI benefits received. The average fiscal impact can be calculated as retirement benefits minus taxes plus UI benefits plus DI benefits (e.g., columns (1)-(2)+(3)+(4) for men). Columns (1) and (5) suggest that for both men and women the pension reforms significantly reduced the average retirement benefits at the ERA and, to a smaller extent, at ages after the ERA. Columns (2) and (6) show that the positive employment effect of the pension reforms translates into sizeable increases in average tax payments at the ERA, and also has some impact on tax payments in the periods pre- and post-ERA. Columns (3) and (7) show that roughly a third of the reduction in retirement benefits at the ERA is compensated by an increase in UI benefits. Because many workers use the UI program as a bridge to regular retirement benefits, increasing the ERA has also important effects on UI benefits in the pre-ERA period. Column (4) indicates that among men average DI benefits at all ages increase, although the effects are relatively small, while for women there is virtually no impact on DI benefits (column (8)).

Based on the estimates in Table 7, we draw the profiles of retirement benefits received, taxed paid, UI benefits received, and DI benefits received by age for different ERAs. Figure 6 shows these profiles for men under the pre-reform ERA of age 60 (solid line) and after it is increased to age 61 (dotted line). Figure 7 displays analogous patterns for women if the ERA is age 55 and after it is raised to age 56. The fiscal effects of an increase in the ERA by one year correspond to the area between the solid and the dotted lines, weighted by the average number of workers in each half-year interval.14 Our estimates imply that a one-year increase in the ERA leads to a permanent reduction in government expenditures for retirement benefits by 126.8 million euros for men and by 104.5 million euros for women. Moreover, as a result of the increase in employment, raising the ERA by one year generates additional tax revenues of 29.2 million euros per year from men and 35.8 million euros from women. The savings in government expenditures, however, are diminished by additional expenditures in the UI and DI programs due to spillover effects. In particular, there are additional expenditures in the UI program of 30.2 million euros for men and 18.4 million euros for women. In addition, DI-expenditures increase by 18.9 million euros among men and decline by 0.1 million euros among women. Overall, we estimate that an increase in the ERA by one year reduces the government budget deficit by 228.9 million euros per year, which is equal to 1.1% of the expenditure in the old-age social security, UI, and DI programs in 2000; 47% of the reductions is generated by men and 53% by women.

Figure 6.

Impact of ERA increase by 1 year on retirement benefits, taxes, UI benefits, and DI benefits by age for men

Notes: This figure displays the impact of the ERA on retirement benefits, taxes, UI benefits, and DI benefits in a given half-year age interval relative to the baseline category (age≥ERA+2). The size of the effect for a particular age interval is obtained by adding up the estimated coefficients from Table 7. For example, if the ERA is 60 the effect of the ERA on retirement benefits in the age interval 60.5-61 (relative to the age group 62-64) is obtained by summing up the estimated coefficients on I(age<ERA+1), I(age<ERA+1.5), and I(age<ERA+2) in column (1) of Table 7. Source: Own calculations, based on Austrian Social Security Data.

Figure 7.

Impact of ERA increase by 1 year on retirement benefits, taxes, UI benefits, and DI benefits by age for women

Notes: This figure displays the impact of the ERA on retirement benefits, taxes, UI benefits, and DI benefits in a given half-year age interval relative to the baseline category (age≥ERA+2). The size of the effect for a particular age interval is obtained by adding up the estimated coefficients from Table 7. For example, if the ERA is 55 the effect of the ERA on retirement benefits in the age interval 55.5-56 (relative to the age group 57-59) is obtained by summing up the estimated coefficients on I(age<ERA+1), I(age<ERA+1.5), and I(age<ERA+2) in column (5) of Table 7. Source: Own calculations, based on Austrian Social Security Data.

Conclusion

Relying on public pensions reforms in Austria, this paper analyzes the impact of an increase in the early retirement age (ERA) on labor supply of older workers. Austria is characterized by a low labor force participation of older workers, only 42% of men and 29% of women aged 55-64 are employed or actively seeking work. With the goal of fostering employment and improving the fiscal health of the public pension system, in 2000 and 2003 the Austrian government implemented a series of changes to the public pension system. The most significant change brought about by the pension reforms was a gradual increase in the early retirement age from 55 to 58.25 for women and from 60 to 62 for men between 2001 and 2010.

Using administrative social security data of Austrian private sector workers, our empirical analysis suggests that the increase in the ERA has significantly delayed retirement pension claims. However, reduced benefit claiming did not lead to a one-for-one increase in employment. In age intervals affected by the ERA increase, employment probabilities increased by 9.75 percentage points for males and 11 percentage points for females. While the reforms had significant employment effects, there were even larger spillover effects to the UI program. Registered unemployment increased by 12.5 percentage points among men and by 11.8 percentage points among women. Spillovers to disability (and other welfare) programs were comparably small. The employment response was largest among healthy, high-wage workers while low-wage workers in poor health either retired through the DI program or they bridged the gap to the new ERA by drawing unemployment benefits.

Taking into account spillover effects and additional tax revenues, we find that a permanent one-year increase in the ERA resulted in a permanent annual reduction of net government expenditures of 107 million euros for men and 122 million euros for women. Our estimates capture the short-run employment effects of the ERA reform. The longer-term effects of this policy change may differ as younger birth cohorts know further in advance that their ERA is higher may react by smoothing their consumption earlier on. This would likely reduce the employment responses of the ERA increase in the long-run.