Abstract

Background

Deep postoperative and hematogenous prosthesis infections may be treated with retention of the prosthesis, if the prosthesis is stable. How long the infection may be present to preclude a good result is unclear.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively studied 89 deep-infected stable prostheses from 69 total hip replacements and 20 total knee replacements. There were 83 early or delayed postoperative infections and 6 hematogenous. In the postoperative infections, treatment had started 12 days to 2 years after implantation. In the hematogenous infections, symptoms had been present for 6 to 9 days. The patients had been treated with debridement, prosthesis retention, systemic antibiotics, and local antibiotics: gentamicin-PMMA beads or gentamicin collagen fleeces. The minimum follow-up time was 1.5 years. We investigated how the result of the treatment had been influenced by the length of the period the infection was present, and by other variables such as host characteristics, infection stage, and type of bacteria.

Results

In postoperative infections, the risk of failure increased with a longer postoperative interval: from 0.2 (95% CI: 0.1–0.3) if the treatment had started ≥ 4 weeks postoperatively to 0.5 (CI: 0.2–0.8) if it had started at ≥ 8 weeks. The relative risk for success was 0.6 (CI: 0.3–0.95) if the treatment had started ≥ 8 weeks. In the hematogenous group, 5 of 6 infections had been treated successfully.

Interpretation

A longer delay before the start of the treatment caused an increased failure rate, but this must be weighed against the advantage of keeping the prosthesis. We consider a failure rate of < 50% to be acceptable, and we therefore advocate keeping the prosthesis for up to 8 weeks postoperatively, and in hematogenous infections with a short duration of symptoms.

The incidence of deep infection in total hip and knee replacement (THR, TKR) ranges from 1% or less in primary THR and TKR to 5% in revision settings (Philips et al. 2006, Willis-Owen et al. 2010), and even up to 21% when revising for infection (Mortazavi et al. 2010). Early deep prosthesis infections are probably caused by peroperative contamination, and in the literature there is agreement that if the prosthesis is stable such an early infection can be treated without removal of the prosthesis, as in early postoperatively infected osteosynthesis (Trampuz and Zimmerli 2006, Choi et al. 2011, Sukeik et al. 2012). The same holds true for hematogenous prosthesis infections (Choi et al. 2011). However, for postoperative infections there is no agreement about the maximal period between implantation of the prosthesis and the start of the treatment that permits retention of the prosthesis, or the duration of symptoms in acute onset of hematogenous infections (Zimmerli et al. 2004, Marculescu et al. 2006).

At our institution, deep postoperative or hematogenous infections of THR and TKR are treated with retention of the prosthesis if they are stable, regardless of interval period since implantation or duration of symptoms. We investigated whether this policy was justified and questioned whether the success rate in postoperative infections does indeed decrease when the postoperative interval since implantation increases or the duration of symptoms in hematogenous infections increases.

Patients and methods

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis of a prospective register of all proven early and delayed deep infections of THR and TKR with a postoperative interval after prosthesis implantation of less than 2 years, and all hematogenous infections treated at our center from January 1982 to July 2010. As hematogenous infections, we considered delayed or late deep infections without any sign of prosthesis infection in the period since implantation. In the databases of the hospital and department, we found 145 infections in 144 patients. For this retrospective analysis, we studied the medical records and if necessary we contacted the patient or family doctor.

Prostheses were diagnosed as infected when the Mayo criteria (Berbari et al. 1998) were fulfilled: growth of the same microorganism in 2 or more cultures of synovial fluid or periprosthetic tissue, or pus in synovial fluid or at the implant site, or histological examination showing acute inflammation in periprosthetic tissue, or a sinus tract communicating with the prosthesis.

We excluded the following patients. 16 patients did not meet Mayo criteria for deep infection, 21 patients got their first surgical treatment at another center, 12 patients were treated by immediate extraction of the prosthesis since unexpected loosening was diagnosed during operation, and 2 patients were excluded because of incomplete patient files. Also excluded were 5 patients with TKR who did not receive any local antibiotic treatment, but only arthroscopic debridement.

After these exclusions, 89 deep infections remained (88 patients, 46 women). All patients and types of infections were scored according to classifications of ASA, Cierny, McPherson, and Zimmerli (Table 1) (Cierny and DiPasquale 2002, McPherson et al. 2002, Zimmerli et al. 2004). There were 69 THR infections (39 primary THR, 30 revisions) and 20 TKR infections (19 primary TKR, 1 revision). 3 of the THR infections and 3 of the TKR infections were hematogenous. One female patient had an early postoperative infection in a primary TKR on both sides, not simultaneously. The first TKR infection was successfully treated, but the contralateral TKR that was subsequently implanted was also infected.

Table 1.

Data on the infected prostheses (69 THRs and 20 TKRs) scored according to the different staging of the host and wound, and classification of the infection. The numbers of THRs and TKRs are given for each subclass, as are the results of the treatments

| THR | TKR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staging or classification | Subclasses | total 69 |

success 57 |

failure 12 |

total 20 |

success 17 |

failure 3 |

| ASAscore patient | ASA1 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| ASA2 | 36 | 30 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 1 | |

| ASA3 | 24 | 19 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| McPherson classification of infection | type I early postop (< 4 weeks) | 42 | 37 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| type II hematogenous | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| type III late postop (> 4weeks) | 24 | 18 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 3 | |

| McPherson host staging | host A: uncompromised | 22 | 19 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| host B: compromised | 38 | 32 | 6 | 13 | 10 | 3 | |

| host C: significant compromised | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| McPherson wound staging | grade 1: uncompromised | 17 | 15 | 2 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| grade 2: compromised | 43 | 37 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 2 | |

| grade 3: significant compromised | 9 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Cierny host staging | A-host: uncompromised | 7 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| B-host: compromised | 62 | 51 | 11 | 15 | 12 | 3 | |

| C-host: significant compromised | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Zimmerli classification of infection | early postop (< 3 months) | 61 | 53 | 8 | 14 | 12 | 2 |

| acute hematogenous | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| delayed exogenous (3–24 months) | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| This study: classification of infection | postop infection < 8 weeks | 60 | 53 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| postop infection ≥ 8 weeks | 6 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 3 | |

| hematogenous | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

The median age of the patients at the start of the infection treatment was 69 (27–93) years. The median interval between implantation of the prosthesis and the first operation for infection in the postoperative THR infections was 23 (12–390) days, and in the TKR infections the median interval was 42 (14–713) days. In some cases, the delay was caused by a period of intravenous antibiotic treatment of a supposed superficial postoperative infection. In 3 hematogenous THR infections, the median duration of symptoms was 7 (6–9) days before the debridement for infection,and in 3 hematogenous TKR infections it was 8 (6-9) days.

No loosening was suspected in any of the implants preoperatively, and this was confirmed peroperatively.

The treatment consisted of arthrotomy, debridement (including pulse lavage with at least 3 L of Ringer lactate), and retention of the implant. In the period studied, we did not exchange modular components if present. The patients were treated with systemic antibiotic therapy, and also with local antibiotic carriers. We preferred the use of gentamicin-PMMA beads with a size of 7 mm, containing 7.5 mg gentamicin sulfate, in the form of chains with 30 or 60 beads (Septopal; Merck GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany; Biomet GmbH, Berlin, Germany). We implanted as much beads as possible in the infected tissues to create a high local gentamicin concentration (Figures 1–3). Beads did not stick through the skin, but were removed in a second operation after 2 weeks. This operation consisted of a new debridement, leaving behind new beads if infection was not considered to be eradicated. If healing was considered appropriate, a much smaller incision was sufficient for the removal of the beads. In several infections, the surgeon implanted gentamicin collagen fleeces (Septocoll containing 116 mg gentamicin sulfate and 350 mg gentamicin crobephate in 320 mg equine collagen fleece with a size of 10 × 8 cm; Merck GmbH; Biomet GmbH) in the joint during the last operation before closing the wound, to increase the period with local antibiotics. If the infection persisted, according to clinical and laboratory parameters and despite one or more treatment periods of 2 weeks with beads, the prosthesis was removed and the treatment for infection continued with gentamicin-PMMA beads.

Figure 1.

Gentamicin-PMMA beads (Septopal) inserted in a total knee replacement after debridement with retained prosthesis. Beads are mainly placed in the suprapatellar bursa and are removed after 2 weeks by another operation under general anesthesia, but with a smaller incision.

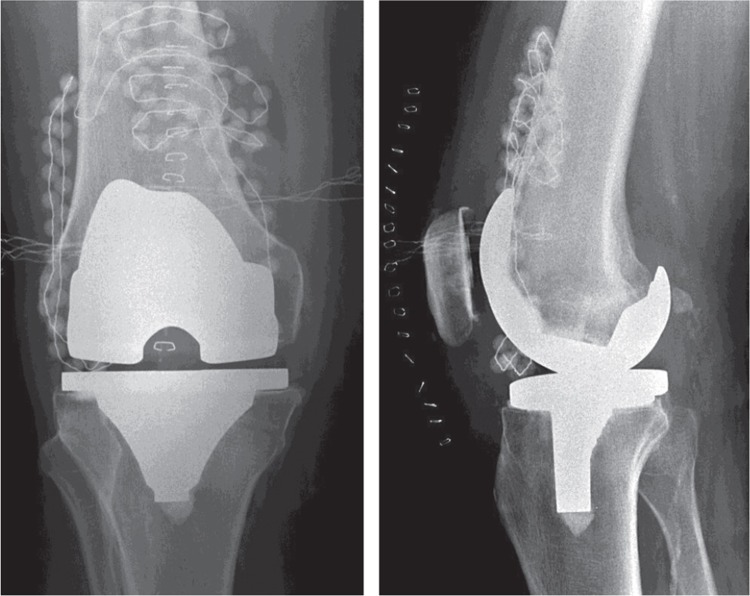

Figure 2.

Radiographic appearance of a TKR in 2 directions. Gentamicin-PMMA beads are visible in the suprapatellar bursa and on the lateral side of the joint. Beads cannot be positioned in the posterior joint due to the limited space.

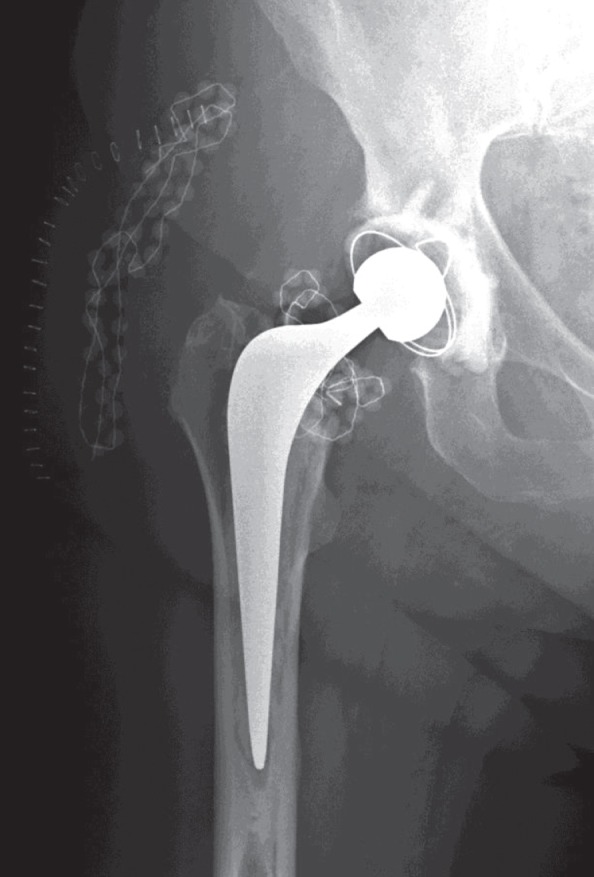

Figure 3.

THR with gentamicin-PMMA beads intra-articularly around the neck of the prosthesis and in the subcutaneous tissues. Antero-posterior radiograph on the first day after the debridement operation. Only a limited number of beads could be placed in this joint after the debridement. In the subcutaneous tissue, beads were placed in an abscess cavity.

Of the infected THRs, 26 of 69 were treated in a single period of 2 weeks with beads or fleeces, and 47 of the 69 THR infections required 2 or more debridements with a subsequent period of 2 weeks of local antibiotics (Table 2). The THR infections were treated with implantation of an average of 180 (30–420) gentamicin beads.

Table 2.

Numbers of debridements and local antibiotic carriers in 89 THR and TKR infections. Detailed numbers are given to specify whether beads were used with or without fleeces (at the last operation), or only fleeces, with numbers of successful or failed treatments

| No of prostheses | No of debridements | Beads ± fleeces | Only fleeces | Success | Failure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THP | ||||||

| 26 | 1 | 26 | 0 | 24 | 2 | |

| 32 | 2 | 32 | 0 | 27 | 5 | |

| 8 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 2 | |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Total | 69 | 69 | 0 | 57 | 12 | |

| TKR | ||||||

| 13 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 12 | 1 | |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Total | 20 | 15 | 5 | 17 | 3 |

Of the infected TKRs, 13 of 20 patients were given a single treatment of 2 weeks of local antibiotics and 7 TKR infections needed 2 or more debridements with local antibiotics for 2 weeks. In 15 of the 20 TKR infections, we implanted an average of 120 (50–240) beads. In the remaining 5 TKR infections, no beads but only gentamicin fleeces were inserted due to limited joint size (Table 2). In the 84 patients who were treated with gentamicin beads, these were removed at the last surgery by a limited operation with a small incision. In 22 of these 84 infections, we implanted 1–4 gentamicin collagen fleeces at this last removal operation of the beads.

Swabs as well as multiple tissue cultures were taken. The samples were cultured in the microbiology laboratory for at least 2 weeks to detect slow-growing microorganisms, and minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of gentamicin for the bacteria were determined. We found methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus to be the most frequent microorganism to cause infections (31/89) (Table 3). In 2 patients, peroperative cultures showed no growth, due to systemic use of antibiotics preoperatively. In the 27 polymicrobial infections, we found 68 bacterial species in many combinations, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter spp. being the most frequent (Table 4).

Table 3.

Causative bacteria in 89 prosthesis infections

| Causative microorganism | THR | TKR | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 26 | 5 | 35 |

| MRSA | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| CNS | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| Streptococci spp. | 6 | 2 | 9 |

| Enterococci spp. | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 5 | 1 | 7 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 4 | 1 | 56 |

| Propionibacterium acnes | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Polymicrobial | 24 | 3 | 30 |

| Negative culture | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 69 | 20 | 100 |

MRSA Methicillin resistent Staphylococcus aureus

CNS Coagulase-negative staphylococci

Table 4.

Bacteria present in the 27 polymicrobial infections as depicted in Table 3

| Microorganisms in polymicrobial culture | THR | TKR |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 14 | 3 |

| CNS | 4 | 0 |

| Streptococcispp. | 4 | 1 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 18 | 0 |

| Enterococci spp. | 2 | 0 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 15 | 1 |

| Propionibacterium acnes | 5 | 0 |

| Prevotella | 0 | 1 |

| Total microorganisms | 62 | 6 |

| No of infections | 24 | 3 |

The MIC values for gentamicin of the causative bacteria were ≤ 8 µg/mL in 71 infections, 16–64 µg/mL in 11 infections, and ≥ 128 µg/mL in 5 infections.

The surgical treatment was combined with high doses of systemic antibiotics, intravenously during hospitalization and continued orally after discharge from hospital. The choice of the antibiotic was based on the resistance pattern of the deep tissue cultures and on consultation with a microbiologist with an interest in orthopedic infections. From 2004, we added rifampicin in the systemic antibiotic treatment of infected implants routinely: thus, 25 of the THR infections and 7 of the TKR infections were also treated with rifampicin. The antibiotic treatment was given for a period of 30 (10–82) days intravenously, followed by an oral treatment over 72 (7–1,310) days. The median total antibiotic therapy time was 95 (12–1,310) days. We stopped the oral antibiotic treatment at the outpatient clinic when clinical and laboratory parameters had normalized for at least 4 weeks.

As laboratory parameters for infection we used ESR, CRP, and WBC counts. These were measured twice a week during hospitalization, and at all the outpatient control visits. We considered these parameters to be normalized when at 2 subsequent controls CRP and WBC counts remained normal, and when the ESR was reduced to less than 30 mm/h in patients with no systemic diseases.

The treatment was considered to be successful when the infection was resolved at follow-up (normalized inflammatory blood markers and no clinical or radiological signs of recurrence) with retention of the prosthesis. Failure was diagnosed if the patient never became infection-free or if removal of the implant was necessary for healing of the infection. The follow-up period started at the first operation for deep infection, and the end of the follow-up period was either the date of the last outpatient clinic visit, the last contact with the family doctor, or the date of death. The minimum follow-up was 1.5 years, but possibly shorter if patients died before—whether or not this was related to the infection. Mean follow-up time was 33 (1–270) months for all infections, 27 (1–270) months for infected THRs, and 52 (3–202) months for infected TKRs.

In the group of postoperative infections, we analyzed how the treatment result was influenced by the length of the interval between implantation of the prosthesis and the start of the treatment. In the hematogenous infections, we studied the influence of the duration of symptoms before the treatment started. We also studied the influence on the result of staging of host and of the wound, of classification of patients, of infection parameters at the start of the treatment, of the causative bacterial species, and of the MIC of gentamicin for the bacteria.

Statistics

Data are presented as median (total range) or as mean (SD). We analyzed the relationship between the result and the length of the postoperative interval using the following steps. For each of the first 10 postoperative weeks, we distinguished 2 periods: the period including and after (≥) a particular week, and the period before (<) that particular week. For both periods, we then estimated the number of failures and successes. Then we estimated first the risk of failure at or after that week. Secondly, we determined the relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for success comparing the results in the period at or after that week with the results obtained before that week. For these calculations, we used Stata 11 for Windows.

Using SPSS version 17.0 for Windows, we calculated RR with CI to determine the influence of the host and wound staging on the result of the treatment. We tested differences between proportions with chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. We used the Mann-Whitney U test to examine the influence of preoperative body temperature, laboratory values, and the MIC of gentamicin for the causative bacteria on the result of the treatment.

Results

Of the 89 infected prostheses, 74 infections were treated successfully with retention and 15 treatments failed.

In the group of postoperative infections, 55 of 66 THRs were treated successfully and 11 treatments failed. 10 of these 11 prostheses were removed at a later stage. In TKR patients, 14 of 17 prostheses were successfully treated. In 3 TKRs there was no successful eradication of infection, resulting in removal of the implant in 2 patients. 2 of the 3 hematogenous THR infections were treated successfully, and 1 failed but became infection-free after extraction of the implant. 3 of 3 hematogenous TKR infections were successfully treated with retention of the implant.

4 patients died during the course of treatment, either because of sepsis or poor health: 3 with THR (at 1, 3, and 8 months after the start of treatment), and 1 with TKR (at 8 months). 8 other patients died of other causes 6–17 months after the treatment started; none of them had signs of infection, so they had probably resolved.

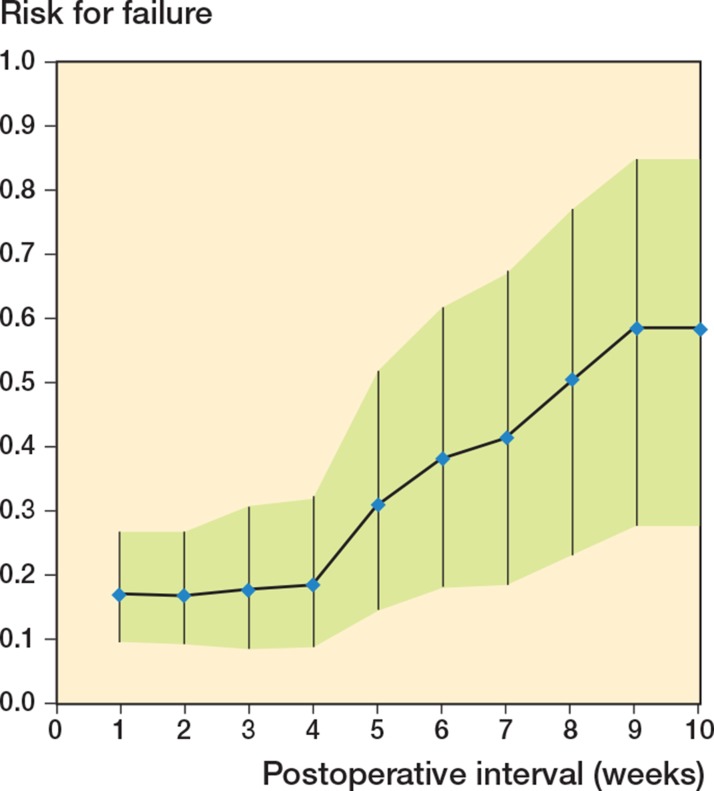

In the first 4 weeks postoperatively, the risk of failed treatment remained almost unchanged and gradually increased thereafter, week by week. The risk of failure in the group of patients where the treatment started ≥ 4 weeks was 0.2 (CI: 0.1–0.3), and it was 0.5 (CI: 0.2–0.8) when the treatment started ≥ 8 weeks (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Risk (with 95% CI) for failure of the treatment of an infected prosthesis if treated at or after a particular postoperative time interval.

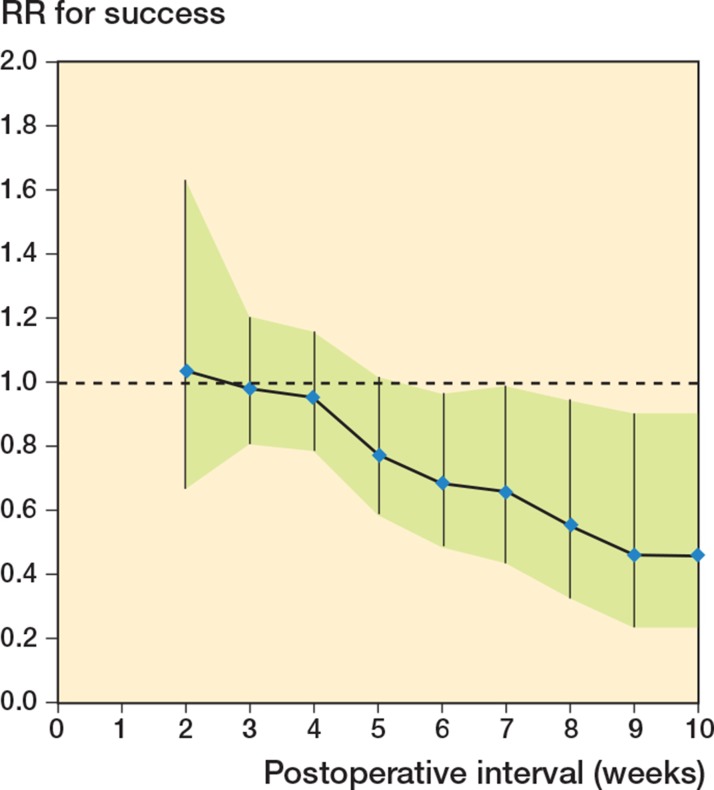

Concerning the RR for successful treatment, we found a gradual decrease in the RR when the postoperative interval increased. If treated ≥ 4 weeks, the RR was 1.0 (CI: 0.8–1.2) compared with < 4 weeks. The RR for success if treated ≥ 8 weeks (compared with treatment < 8 weeks) was 0.6 (CI: 0.3–0.95) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Relation between the relative risk (RR) for successful treatment of an infected prosthesis and the postoperative interval in weeks. The RR is expressed as success if a treatment started after ≥ N weeks, as compared to the period < N weeks. The null hypothesis of RR = 1.0 is represented by a broken line.

In the group of patients where the treatment started ≥ 8 weeks, 7 of 14 infections healed (Table 1). Of the 6 THR infections, 2 infections healed despite retention of the prosthesis. In the remaining 4 patients, the THR had to be extracted, resulting in resolution of infection in 2. Of the 8 TKR infections, 5 healed. In the remaining 3, the implant was removed, and 2 of these infections resolved. Thus, altogether, in 11 of 14 prostheses the infection eventually healed despite an interval of more than 8 weeks after implantation. 7 of these 11 infections became infection-free without extraction, even with an interval of almost 1 year postoperatively.

In the 6 hematogenous THR and TKR infections, we found no correlation between the duration of symptoms and the results of the treatment with retention of the prosthesis.

In the infections that were difficult to treat, more debridements were needed, but the failure rate increased (Table 2). 8 of the 11 infections that were debrided for a third time healed, but when a fourth debridement was necessary none of the 3 infections healed.

ASA score, type of infection, host and wound staging, number of interventions, or preoperative infection parameters such as fever or laboratory values were similar in the success group and the failure group. We found no relation between the result of the treatment and the causative bacteria. Neither a difference in the result of the treatment between gram positive and gram negative bacteria, or between staphylococci and streptococci. We found no influence of the use of rifampicin, which was added to the treatment protocol since 2004. There was no association between the MIC of gentamicin for the causative bacteria and the success rate of the treatment.

Discussion

We found good results if we treated deep-infected stable THRs and TKRs by debridement and retention of the prosthesis, in combination with systemic and local antibiotics. Removal of a stable, well-fixed implant is associated with high morbidity and mortality. So the treatment of an infected implant without removal is attractive. Since the results vary greatly, with success rates between 31% and 100% (Mont et al. 1997, Azzam et al. 2010, Gardner et al. 2011, Koyonos et al. 2011, Sukeik et al. 2012, Fehring et al. 2013, Lee et al. 2013), retention of the implant remains controversial. The controversy is, however, less focused on the treatment with retention as such, and more on the interval after which the results become too bad.

We therefore focused on the delay in the start of treatment in relation to the results. We could quantify the risks for failure and success of the treatment postoperatively up to 10 weeks. The treatment had a low and almost unchanged risk of failure up to an interval of 4 weeks, and thereafter it increased every week (Figure 4). The RR for successful treatment showed a gradual decrease in these first weeks, and after 8 weeks there was significantly more risk of failure (as indicated by its CI) (Figure 5). The smaller numbers of infections treated after 10 weeks justifies limitation of our conclusions to only these intervals.

When we consider the balance between the disadvantages of the removal of a prosthesis on the one hand and the failure rate of a treatment with retention on the other, we prefer a retention up to 8 weeks postoperatively.

Several authors reported a cut-off of only a few days of symptoms for successful retainment of a prosthesis after a deep infection (Brandt et al. 1997, Tattevin et al. 1999, Meehan et al. 2003). Most authors consider a postoperative interval of 2–4 weeks to be the maximum period that a prosthesis can be retained (Theis et al. 2007, Kim et al. 2011). Some studies have suggested that this period could be longer (Schoifet and Morrey 1990, Mont et al. 1997, Zimmerli et al. 2004). Currently, the algorithm by Zimmerli et al. is the one most commonly used (Giulieri et al. 2004, Zimmerli et al. 2004). In their algorithm, they limit the acceptable period of symptoms to a maximum of 3 weeks if the prosthesis is stable, the soft tissues are in good condition, and an antibiotic with activity against biofilm is available.

However, confusingly, in the literature 2 different periods are used in protocols: the duration of symptoms and the postoperative period since implantation (“joint age”) (Gardner et al. 2011). The recent guideline of the Infectious Diseases Society of America uses a limit for in situ treatment of 3 weeks of symptoms, and also a joint age of less than 30 days (Osmon et al. 2013). We regard the postoperative period as a clearer guideline, since the onset of symptoms of a deep infection is very difficult to estimate in clinical practice. Another argument is that these infections must be regarded as having been caused by contamination during the implantation operation.

In some patients, an even higher risk of failure with an interval of more than 8 weeks might be acceptable. In 14 of our patients who were treated after such a long interval, the infection resolved in 7 cases with retention of the prosthesis, and in 4 after extraction, so the result for healing of infection was 11 out of 14. This result is comparable with results in the literature when the postoperative infection was treated with early extraction, with reimplantation in 1 or 2 stages (Raut et al. 1994, Jämsen et al. 2009).

As we do, Kim et al. (2011) also advocated repeated debridement, but their advice was to stop and remove the prosthesis after 4 attempts. In our patients, no infections healed when debridement was performed more than 3 times, so in our hands extraction after 3 debridements appears to be justified.

Comparing our results with those in the literature, they are relatively good, despite an often long postoperative interval. One explanation for this could be the consistent use of local antibiotic carriers in our treatments, with gentamicin-loaded beads or collagen. The high local gentamicin concentration is important, since the infection is probably limited to recently operated tissues, which will be accessible for the debridement and local antibiotic carriers.

In 28-year study period, our treatment protocol remained essentially unchanged, focusing on retainment of the implant and on the use of local antibiotic carriers, to supplement systemic antibiotics. The main advantage of gentamicin-PMMA beads is a high local antibiotic concentration at the site of the infection, without systemic toxic side effects (Walenkamp et al. 1986). A disadvantage of beads is the space needed, and they have to be removed with an extra operation. The removal operation can, however, be performed with a smaller incision, permitting local inspection, deep cultures, and if necessary a repeated debridement. Gentamicin collagen fleeces have the advantage that they are resorbable and have less volume, which makes insertion easier, especially in TKR infections, and removal unnecessary. In our experience, however, a disadvantage of fleeces is increased wound secretion up to 6 weeks postoperatively, causing difficulties in wound control. Also, they release most of their antibiotics in the first 1–2 hours of implantation (Sørensen et al. 1990).

During the study period, we did not replace polyethylene components or modular heads, but we have been doing this routinely since 2010. We found more S. aureus infections than CNS infections. This can be explained since S. aureus causes more acute infections (Gardner et al. 2011), and CNS with a lower virulence are more frequently seen in low-grade and late infections (Giulieri et al. 2004).

We found no association between the result of the treatment and the MIC of gentamicin for the bacteria, but even high MIC values are not an absolute contraindication for the use of gentamicin beads or fleeces. These MIC values are based on systemic gentamicin treatment, and in a treatment with local antibiotic carriers the local gentamicin concentrations are much higher, up to several hundreds of µg/mL (Wahlig et al. 1978, Hedström et al. 1980, Walenkamp et al. 1986) .

The present study had some limitations. It was a retrospectively studied cohort, and the treatment was performed by several orthopedic surgeons. We combined the data on postoperative infections of THRs and TKRs, and the cohort included both primary and revision implantations. However, there were also some strong points: the patients were treated at a single center with an almost unchanged protocol for 28 years, treating the infections in the same way with local antibiotics. Although several debridements were performed by different colleagues at the department, a single surgeon was responsible for the treatment of the patients over the whole period. As our department has a “last-resort function” in treating infections, loss to follow-up was low. We were able to follow the patients for at least 1.5 years if they were still alive. Instead of presenting the results of the treatment as percentages of healing, as in most studies in the literature, we were able to calculate the relative effect of the treatments to show the estimation uncertainty, especially regarding variation in the postoperative interval.

In conclusion, treatment of THR or TKR infections can be performed with retention of the prosthesis when the implant is stable. The use of local antibiotics is probably helpful. In postoperative infections, a gradually increased risk of failure of the treatment should be weighed by each surgeon against the disadvantages of removal of the prosthesis. We consider a risk of failure of 50%, if treatment occurs within 8 weeks in most patients, to be acceptable. This approach can still be considered for even longer postoperative intervals in some patients, although we cannot identify these specific patients.

Acknowledgments

JG and GW treated the patients, designed the study and wrote the manuscript. DJ collected the data of the medical records, completed the follow-up, and performed statistical analyses. AK supervised and helped in the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data and to the revisions of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Azzam KA, Seeley M, Ghanem E, Austin MS, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Irrigation and debridement in the management of prosthetic joint infection: traditional indications revisited . J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1022–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbari EF, Hanssen AD, Duffy MC, Steckelberg JM, Ilstrup DM, Harmsen WS, et al. Risk factors for prosthetic joint infection: case-control study . Clin Inf Dis. 1998;27(5):1247–54. doi: 10.1086/514991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt CM, Sistrunk WW, Duffy MC, Hanssen AD, Steckelberg JM, Ilstrup DM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection treated with debridement and prosthesis retention . Clin Inf Dis. 1997;24(5):914–9. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H-R, von Knoch F, Zurakowski D, Nelson S, Malchau H. Can implant retention be recommended for treatment of infected TKA? . Clin Orthop. 2011;469(4):961–9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cierny G, DiPasquale D. Periprosthetic total joint infections: staging, treatment, and outcomes . Clin Orthop. 2002;(403):23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehring TK, Odum SM, Berend KR, Jiranek WA, Parvizi J, Bozic KJ, et al. Failure of irrigation and débridement for early postoperative periprosthetic infection . Clin Orthop. 2013;(471):250–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2373-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner J, Gioe TJ, Tatman P. Can this prosthesis be saved?: implant salvage attempts in infected primary TKA . Clin Orthop. 2011;469(4):970–6. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1417-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulieri S, Graber P, Ochsner P, Zimmerli W. Management of infection associated with total hip arthroplasty according to a treatment algorithm . Infection. 2004;32(4):222–8. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-4020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedström SÅ, Lidgren L, Torholm C, Onnerfalt R. Antibiotic containing bone cement beads in the treatment of deep muscle and skeletal infections . Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51(6):863–9. doi: 10.3109/17453678008990886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jämsen E, Stogiannidis I, Malmivaara A, Pajamaki J, Puolakka T, Konttinen YT. Outcome of prosthesis exchange for infected knee arthroplasty: the effect of treatment approach . Acta Orthop. 2009;80(1):67–77. doi: 10.1080/17453670902805064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Kim JS, Park JW, Joo JH. Cementless revision for infected total hip replacements . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93(1):19–26. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.25120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyonos L, Zmistowski B, Della Valle CJ, Parvizi J. Infection control rate of irrigation and débridement for periprosthetic joint infection . Clin Orthop. 2011;(469):3043–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1910-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YK, Lee KH, Nho JH, Ha YC, Koo KH. Retaining well-fixed cementless stem in the treatment of infected hip arthroplasty. Good results in 19 patients followed for mean 4 years . Acta Orthop. 2013;84(3):260–4. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.795830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marculescu CE, Berbari EF, Hanssen AD, Steckelberg JM, Harmsen SW, Mandrekar JN, et al. Outcome of prosthetic joint infections treated with debridement and retention of components . Clin Inf Dis. 2006;42(4):471–8. doi: 10.1086/499234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson E, Woodson C, Holtom P, Roidis N, Shufelt C, Patzakis M. Periprosthetic total hip infection . Clin Orthop. 2002;(403):8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan AM, Osmon DR, Duffy M CT, Hansen AD, Keating MR. Outcome of penicillin-susceptible streptococcal prosthetic joint infection treated with debridement and retention of the prosthesis . Clin Inf Dis. 2003;36:845–9. doi: 10.1086/368182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mont M, Waldman R, Banerjee C, Pacheco I, Hungerfors D. Multiple irrigation, debridement, and retention of components in infected total knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 1997;12(4):426–33. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi SM, Schwartzenberger J, Austin MS, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Revision total knee arthroplasty infection: incidence and predictors . Clin Orthop. 2010;468(8):2052–9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1308-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Behrendt AR, Lew L, Zimmerli W, Stecklenberg JM, et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America . Clin Inf Dis. 2013;56:1–25. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips J, Crane T, Noy M, Elliot T, Grimer R. The incidence of deep prosthetic infections in a specialist orthopaedic hospital: a 15 year prospective survey . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006;88:943–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B7.17150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raut VV, Siney PD, Wroblewski BM. One-stage revision of infected total hip replacements with discharging sinuses . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994;76(5):721–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoifet S, Morrey B. Treatment of infection after total knee arthroplasty by debridement with retention of the components . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1990;72:1383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen TS, Sørensen AI, Merser S. Rapid release of gentamicin from collagen sponge. In vitro comparison with plastic beads . Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61(4):353–6. doi: 10.3109/17453679008993535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukeik M, Patel S, Haddad FS. Aggressive early debridement for treatment of acutely infected cemented total hip arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2012;(470):3164–70. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2500-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tattevin P, Cremieux AC, Pottier P, Huten D, Carbon C. Prosthetic joint infection: when can prosthesis salvage be considered? . Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(2):292–5. doi: 10.1086/520202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis JC, Gambhir S, White J. Factors affecting implant retention in infected joint replacements . ANZ J Surg. 2007;77(10):877–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trampuz A, Zimmerli W. Diagnosis and treatment of infections associated with fracture-fixation devices . Injury. 2006;37:S59–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlig H, Dingeldein E, Bergmann R, Reuss K. The release of gentamicin from polymethylmethacrylate beads. An experimental and pharmacokinetic study . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1978;60(2):270–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.60B2.659478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walenkamp G H IM, Vree TB, van Rens T JG. Gentamicin-PMMA beads. Pharmacokinetic and nephrotoxicological study . Clin Orthop. 1986;(205):171–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis-Owen C, Konyves A, Martin D. Factors affecting the incidence of infection in hip and knee replacement: an analysis of 5277 cases . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92:1128–33. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B8.24333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner P. Prosthetic-joint infections . N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]