Abstract

Background and purpose

There are several diagnostic tests for periprosthetic joint infection (PJI). We evaluated the properties of preoperative serum C-reactive protein (CRP), real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and histopathological evaluation of frozen and permanent sections in clinical cases with culture-positive PJI.

Patients and methods

63 joints involving 86 operations were analyzed using serum CRP measurement prior to operation and tissue samples were collected intraoperatively for real-time PCR and histopathology. We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio of positive test results (PLR), and likelihood ratio of negative test results (NLR) for each test in relation to positive microbiological culture results as the gold standard.

Results

The sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis with serum CRP were 90% and 85%, respectively. The corresponding values for real-time PCR and histopathology of frozen and paraffin tissue sections were 90% and 45%, 71% and 89%, and 90% and 87%, respectively. Serum CRP had a PLR of 5.8 and an NLR of 0.12, and real-time PCR had a PLR of 1.6 and an NLR of 0.18. The corresponding figures for frozen tissue sections were 6.6 and 0.32, and those for paraffin sections were 7.1 and 0.11, respectively.

Interpretation

The results suggest that real-time PCR and histopathology of frozen sections is a good combination. The former is suitable for screening, with its high sensitivity and good NLR, while the latter is suitable for definitive diagnosis of infection, with its excellent specificity and good PLR.

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is still commonly regarded as a challenge, especially in terms of diagnosis (Bauer et al. 2006). Conventional culture methods were long regarded as the gold-standard test for diagnosing PJI; however, several recent studies have shown that this approach has limited accuracy, particularly in low-grade infections that often cause false-negative results (Tunney et al. 1999, Kobayashi et al. 2008). Since no particular method has been able to provide definitive information (Bare et al. 2006), a more comprehensive approach is needed.

For the diagnosis of PJI, we used serum C-reactive protein (CRP) measurement as a preoperative diagnostic tool, frozen histopathologic evaluation and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as intraoperative tools, and permanent histopathological evaluation and microbiological culture as postoperative tools. We have previously reported the usefulness of an intraoperative real-time PCR assay after sonication (Esteban et al. 2012) for the detection and quantification of PJI. This was found to be a rapid method capable of specifically identifying methicillin resistance (Kobayashi et al. 2009, Miyamae et al. 2012). Histopathological evaluation is thought to be reliable in the diagnosis of bacterial infections because of its high specificity, but previous reports have indicated that intraoperative analysis using frozen sections has poor sensitivity (Della Valle et al. 1999, Kanner et al. 2008). Because the premises of these diagnostic tests are basically different (quantification of a protein induced by inflammatory responses (CRP), bacterial DNA in PCR, and neutrophil infiltration in histopathology), their sensitivity and specificity might also be different. In this study, we compared the properties of each diagnostic test—including the sensitivity and specificity of preoperative serum CRP, real-time PCR, and histopathology of frozen and paraffin tissue sections—in clinical cases with PJI, using the culture result as the definitive diagnostic test.

Patients and methods

This retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board. From January 2007 through June 2012, 63 joints from 86 operations were enrolled in this study. These operations included 63 hip surgeries (16 1-stage revision arthroplasties, 28 2-stage revision arthroplasties, and 19 implant removals), 13 knee surgeries (8 2-stage revision arthroplasties and 5 implant removals), and 10 debridement surgeries, for suspected infection or aseptic loosening. 15 patients were treated with antibiotics within a week of the surgical procedure. Of these 15 patients, 9 received antibiotics for chronic suppression during the period from the last operation to the next operation, 4 patients received antibiotics for several days before the first operation because of a strong suspicion of infection, and 2 patients received antibiotics for other diseases.

In all cases, serum CRP was measured just before each operation, and tissue samples were collected intraoperatively for real-time PCR, histopathology (using frozen and paraffin tissue sections), and for microbiological culture. The intraoperative tissue samples were collected from 3 different places for each test; also, in 51 cases joint fluids were collected for microbiological culture. 5 cases with inflammatory disease (2 with rheumatoid arthritis, 2 with malignant tumors, and 1 with systemic lupus eryhtematosus (SLE)) were excluded because of the possible influence on the tests. Thus, we analyzed the remaining 81 cases for serum CRP, PCR, paraffin histopathology, and microbiological culture, and 71 cases for frozen histopathology data. No cases in our cohort had other inflammatory diseases that could be found on routine examination.

Serum CRP

With respect to serum CRP value, we set the cutoff to 1.0 mg/dL for the diagnosis of infection, based on the results of receiver operating characteristic analysis (data not shown).

Real-time PCR

Intraoperative real-time PCR assays were performed as described previously (Kobayashi et al. 2009). Briefly, for manual DNA extraction, samples from the operating room underwent ultrasonication (Bransonic 2510 Ultrasonic cleaner; Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT) at a frequency of 40 kHz for 5 min using a plastic bag and 1 mL sterile water. The sonicated solutions were collected and then applied to a DNA purification column (QIAamp DNA Mini Kit; QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). A universal PCR assay (LightCycler; Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN) that targeted the 16S rRNA gene was performed for the broad detection of microbes and for quantitative analysis, while an MRS-PCR assay that targeted the mecA gene was performed for specific detection of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus (MRS). Using a universal PCR, the differences in threshold cycles between clinical samples and negative control (ΔCt) were calculated in each case based on the LightCycler quantification mode. We regarded cases as infected with over 1.9 cycles of ΔCt or with the detection of MRS in at least 1 sample (Miyamae et al. 2012).

Histopathology

Postoperative histopathological analysis of the intraoperative frozen and paraffin tissue sections was performed by 2 specialists of pathology certified by the Japanese Society of Pathology. We regarded cases with more than 10 neutrophils per high-power field (HPF) to be infected (400× magnification, with a field diameter of 0.6 mm and 5 fields counted) (Lonner et al. 1996, Banit et al. 2002).

Microbiological culture

All specimens were analyzed using standard microbiological cultures with a direct plating method and broth medium. The culture was scored as positive if the same bacterial organism was identified in at least 2 different tissue or joint fluid samples.

Statistics

We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio of positive test results, and likelihood ratio of negative test results for serum CRP value, real-time PCR, and histopathology of frozen and permanent sections using the culture result as a reference.

Results

In the evaluation of preoperative serum CRP levels, excluding 5 inflammatory cases there were 61 cases with a CRP level of less than 1.0 mg/dL and 20 cases with a serum CRP level of over 1.0 mg/dL. The mean CRP value was 1.7 (0–21) mg/dL. Real-time PCR gave 33 negative and 48 positive results. Pathological evaluation of frozen sections gave 59 negative and 12 positive results. Pathological evaluation of paraffin sections gave 63 negative and 18 positive results. Microbiological culture gave 71 negative and 10 positive results.

The results of serum CRP measurement, real-time PCR, histopathology, and culture from the 10 cases where some organisms grew in culture are summarized in Table 1. The sensitivity and specificity of the diagnosis using serum CRP were 90% and 85%, respectively. Those of real-time PCR, histopathology of frozen sections, and histopathology of paraffin sections were 90% and 45%, 71% and 89%, and 90% and 87%, respectively (Table 2). Serum CRP had a likelihood ratio of positive test results of 5.8, and a likelihood ratio of negative test results of 0.12. Real-time PCR had corresponding figures of 1.6 and 0.18, histopathology of frozen sections 6.6 and 0.32, and histopathology of paraffin sections 7.1 and 0.11, respectively (Table 3). There was concordance between diagnosis evaluated by frozen and paraffin sections in 68 cases (90%).

Table 1.

Cases in which organisms were detected by culture, and the corresponding results regarding PCR, histopathology of frozen and paraffin sections, culture, and serum CRP preoperatively

| Case | PCR result | Histopathology result | Culture result | Preoperative serum CRP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| frozen | paraffin | ||||

| 1 | P | P | P | MRSA | 19 |

| 2 | P | N | P | MRSE | 0.42 |

| 3 | P | P | P | MRSA | 21 |

| 4 | P | N/A | P | Streptococcus | 10 |

| 5 | P | N/A | P | S. agalactiae | 9.0 |

| 6 | P | N/A | P | MSSA | 17 |

| 7 | P | P | P | Streptococcus | 1.4 |

| 8 | P | N | P | Streptococcus | 1.5 |

| 9 | P | P | P | MRSE | 1.5 |

| 10 | N | P | N | Peptostreptococcus | 2.6 |

CRP: C-reactive protein;

MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus;

MRSE: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis;

MSSA: methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus;

N: negative; N/A: not applicable; P: positive;

PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of preoperative serum CRP, PCR, and histopathology of frozen and paraffin sections

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP value (cutoff: 1.0) | 90 | 85 | 45 | 98 |

| Real-time PCR | 90 | 45 | 19 | 97 |

| Frozen sections | 71 | 89 | 42 | 97 |

| Paraffin sections | 90 | 87 | 50 | 98 |

CRP: C-reactive protein; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

Table 3.

Likelihood ratio of positive test results (PLR), likelihood ratio of negative test results (NLR), diagnostic odds ratio, and 95% confidence interval (CI) for preoperative serum CRP value, PCR, and histopathology of frozen and paraffin sections

| PLR | NLR | Diagnostic odds ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP value (cutoff, 1.0) | 5.8 | 0.12 | 49 | 7–323 |

| Real-time PCR | 1.6 | 0.18 | 7 | 1.1–49 |

| Frozen sections | 6.6 | 0.32 | 20 | 4–109 |

| Paraffin sections | 7.1 | 0.11 | 62 | 9–414 |

For abbreviations, see Table 2.

In the 15 patients who had received antibiotics before surgery, 3 cases were culture-positive, and all 3 cases had high serum CRP value (> 9.0mg/dL) with acute onset, and were therefore were given antibiotics for several days. 12 cases of those 15 were culture-negative and 11 of these 12 cases were treated with antibiotics for chronic suppression, for weeks or months. Real-time PCR detected a microorganism in 9 cases out of the 12 culture-negative cases.

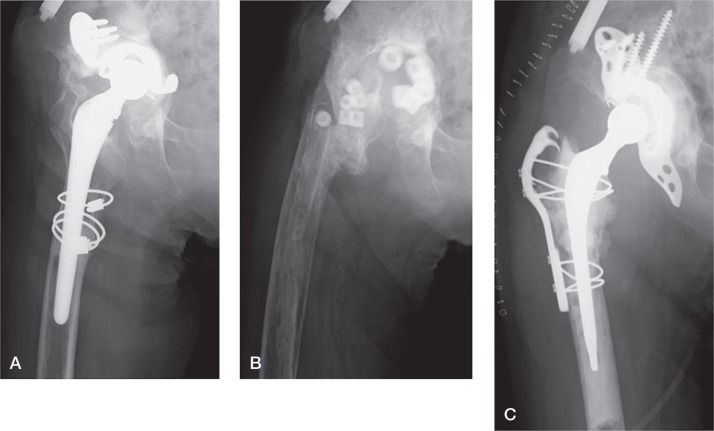

Case 2 was a case with unclear infection (Figure 1). The preoperative serum CRP value was 0.42 mg/dL, and the patient underwent surgery with suspicion of PJI. Intraoperative histopathology showed negative results, but real-time MRS-PCR revealed positive findings; we therefore diagnosed infection with MRS and performed implant removal. Also, the result of histopathology of paraffin sections was positive, and culture revealed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. After 3 months, a 2-stage revision was performed after intraoperative confirmation of a negative result by real-time PCR.

Figure 1.

A representative case with unclear infection (case 2). A. Preoperative plain radiograph. B. Plain radiograph after the first operation. Implant removal and antibiotic-loaded hydroxyapatite block replacement were performed. C. Plain radiograph after the second operation.

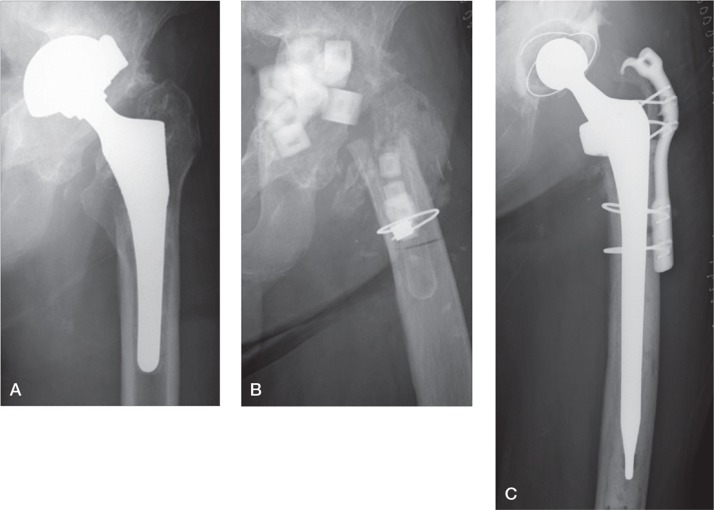

Case 8 was a representative case of PJI (Figure 2). This patient with a hip prosthesis had a preoperative serum CRP value of 1.36 mg/dL, which led to a strong suspicion of PJI, and the patient underwent surgery. Intraoperative histopathological findings were positive with substantial neutrophil counts, and an implant removal was performed. As expected, the supplementary PCR result was also positive. In postoperative tests, histopathological findings of paraffin sections were the same as intraoperative findings, and the culture was positive for streptococcus.

Figure 2.

A representative case of periprosthetic joint infection (case 8). A. Preoperative plain radiograph, showing cup migration. B. Plain radiograph after the first operation. Implant removal and antibiotic-loaded hydroxyapatite block replacement were performed. C. Plain radiograph after the second operation.

Discussion

A combination of several different tests, which have different sensitivities and specificities, is essential for accurate diagnosis of PJI. Recent recommendations in clinical guidelines have included erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and serum CRP testing, hip or knee aspiration, frozen sections of intraoperative tissue in patients undergoing reoperation, and multiple cultures for the assessment of PJI (Della Valle et al. 2011). Up-and-coming tests, mentioned not only in guidelines but also in some recent studies, include aspirated or intraoperatively collected joint fluid, analyzed particularly for white blood cell (WBC) count or differential (Parvizi et al. 2011). In this study, we compared results from serum CRP, real-time PCR, and histopathology of frozen and paraffin sections with culture results.

Serum CRP measurement, which is available in most hospitals, still has an important role in the diagnosis of periprosthetic infections. Furthermore, serum CRP is strongly recommended as the best way to rule out PJI, and it is more effective when combined with ESR (Della Valle et al. 2011). When PJI is suspected based on serum CRP or ESR, supplementary assay examinations such as joint aspiration should be done (Della Valle et al. 2011). We ascertained that serum CRP determination had sufficient sensitivity and specificity with a cutoff value of 1.0 mg/dL, which has also been recommended in recent guidelines (Della Valle et al. 2011). PCR-based assays for the detection and quantification of viral or bacterial infections have been useful in some fields (Yang et al. 2005, Darton et al. 2009, Peters et al. 2009). Although some reports have shown that PCR is not superior to microbiological culture (Ince et al. 2004), the majority of these studies have highlighted the usefulness of PCR-based techniques for the diagnosis of PJI (Mariani et al. 1996, Tunney et al. 1999, Tarkin et al. 2003, Clarke et al. 2004, Gomez et al. 2012). We have previously described the usefulness of intraoperative identification of bacterial DNA by PCR for the diagnosis of PJI, and we reported a comparatively high sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 80% in clinical use (Kobayashi et al. 2009). We have also shown the usefulness of real-time PCR for the quantitative evaluation of PJI, and we confirmed that there was a positive correlation between these results and preoperative serum CRP values, microbiological culture results, and severity of tissue pathology (Miyamae et al. 2012).

In general, patients with suspicion of PJI who are undergoing surgery should be analyzed using frozen sections (Della Valle et al. 2011, Tsaras et al. 2012). Some studies have suggested that evaluation of the neutrophils in frozen sections is useful for diagnosis of periprosthetic infection, with a higher number of invasive neutrophils signifying a higher suspicion of infection. However, previous reports have suggested that intraoperative analysis using frozen sections has poor sensitivity in this regard (Della Valle et al. 1999, Kanner et al. 2008). One should therefore use supplementary intraoperative tests with high sensitivity, including real-time PCR.

In this study, we confirmed that serum CRP has a high sensitivity equal to that of PCR and a high specificity close to that of histopathology, which supports the recommendation to use serum CRP for preoperative screening of PJI. Although this is still unclear in low-grade infections, such as culture-negative cases, we confirmed that there was satisfactory performance of serum CRP at least in culture-positive cases. As for intraoperative evaluation of PJI, we found that real-time PCR is useful for screening of infections, with its high sensitivity and good negative likelihood ratio, while histopathological evaluation is suitable for definitive diagnosis of infection, with its excellent specificity and good positive likelihood ratio. These 2 different characteristics, sensitivity of PCR and specificity of histopathology, make them a reasonable combination for accurate intraoperative diagnosis.

Occasionally, we face cases that are PCR-positive and histopathology-negative, or vice versa. This discrepancy between diagnostic tests can be caused by several factors, such as preoperative antibiotic treatment or infection with low-virulence bacteria (Bori et al. 2009). In such cases, the properties of each diagnostic test should be considered. In some cases such as case 2, we could not diagnose infection confidently with serum CRP value and a negative histopathology result; however, the positive result from real-time PCR gave suspicion of infection, with its high sensitivity. In these instances, the possibility of low-grade infection should be kept in mind. On the other hand, in cases with strong suspicion of infection from preoperative evaluation, such as case 8, the positive histopathological result was important for a definitive diagnosis, with its high specificity.

The present study allowed comparison of the histopathology of frozen and paraffin sections. Generally, a discrepancy between the findings from frozen and paraffin sections may occur due to differences in the quality of the sections. Several reports have indicated that analysis of frozen sections agrees with that of paraffin sections (Lonner et al. 1996, Stroh et al. 2012), whereas another report showed a lower concordance rate (Tohtz et al. 2010). Stroh et al. (2012) reported a high concordance rate of 97%, in which a mean of greater than 5 polymorphonuclear leukocytes per HPF was the criterion for positive diagnosis. Tohtz et al. (2010) reported a relatively low concordance rate of 78%, in which pathological findings were classified according to the score of a consensus classification (Morawietz et al. 2006). In the current study, although analysis of frozen sections showed lower sensitivity than analysis of paraffin sections or other tests, we confirmed that it has as high a specificity as analysis of paraffin sections. Also, from this point of view frozen sections appear to be suitable for definitive diagnosis.

One major limitation of our study was that we used only microbiological culture results as the definitive diagnostic criterion, which possibly overlooked cases of infection that were culture-negative. Culture-negative PJI should also have been included in our series. For example, when we diagnosed PJI based on the combination of histopathology, PCR, and culture in our previous work, culture-negative but histopathology-positive or PCR-positive cases existed (Kobayashi et al. 2009). In the present series, there were 4 cases of serum CRP-positive, PCR-positive, histopathology-positive but culture-negative results, which could have been low-grade infection. However, the aim of this study was not to evaluate the reliability of diagnostic tests, but to compare their properties. For that purpose, we needed to have one independent criterion to compare several different tests impartially, and that is why we used only microbiological culture as the diagnostic criterion or as a reference test. Another limitation is that the influence of antibiotics on the results should be considered. 15 patients were treated with antibiotics within a week of the surgical procedure. The antibiotic treatment possibly affected the results of microbiological culture, PCR, and histopathology. In addition, we must consider the effect of underlying inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis. We excluded 5 such cases from the series.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated several important points. First, serum CRP was re-affirmed to be useful as a preoperative screening test for PJI, with its high sensitivity. Second, real-time PCR and histopathological evaluation of frozen sections have different, valuable roles in intraoperative diagnosis of PJIs. It is important to consider their different characteristics when using several tests simultaneously for diagnosis of PJI. In addition, we confirmed that histopathology of frozen section has a high specificity which is equal to that of paraffin sections, although its sensitivity is lower.

Acknowledgments

YM: design of the study, patient follow-up, surgery, PCR, and preparation of the manuscript. YI: design of the study, surgery, preparation of the manuscript, and supervision. NK: design of the study, surgery, PCR investigations, pathology, PCR, preparation of the manuscript, and supervision. HC, YY, and HI: patient follow-up and surgery. TS: design of the study, preparation of the manuscript, and supervision.

We thank laboratory technician Kimi Ishikawa for performing the real-time PCR procedure and for management of the LightCycler system. No financial support was received for this work.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Banit DM, Kaufer H, Hartford JM. Intraoperative frozen section analysis in revision total joint arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2002;401:230–8. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200208000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bare J, MacDonald SJ, Bourne RB. Preoperative evaluations in revision total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2006;446:40–4. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000218727.14097.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer TW, Parvizi J, Kobayashi N, Krebs V. Diagnosis of periprosthetic infection . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88(4):869–82. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bori G, Soriano A, Garcia S, Gallart X, Mallofre C, Mensa J. Neutrophils in frozen section and type of microorganism isolated at the time of resection arthroplasty for the treatment of infection . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(5):591–5. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0679-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MT, Roberts CP, Lee PT, Gray J, Keene GS, Rushton N. Polymerase chain reaction can detect bacterial DNA in aseptically loose total hip arthroplasties . Clin Orthop. 2004;427:132–7. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000136839.90734.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darton T, Guiver M, Naylor S, Jack DL, Kaczmarski EB, Borrow R, Read RC. Severity of meningococcal disease associated with genomic bacterial load . Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):587–94. doi: 10.1086/596707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Valle CJ, Bogner E, Desai P, Lonner JH, Adler E, Zuckerman JD, Di Cesare PE. Analysis of frozen sections of intraoperative specimens obtained at the time of reoperation after hip or knee resection arthroplasty for the treatment of infection . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1999;81(5):684–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199905000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Valle C, Parvizi J, Bauer TW, DiCesare PE, Evans RP, Segreti J, Spangehl M, Watters WC. 3rd, Keith M, Turkelson CM, Wies JL, Sluka P, Hitchcock K. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on: the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infections of the hip and knee . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011;93(14):1355–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.9314ebo. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban J. Alonso-Rodriquez N, del-Prado G, Ortiz-Perez A, Molina-Manso D, Cordero-Ampuero J, Sandoval E, Fernandez-Roblas R, Gomez-Barrena E. PCR-hybridization after sonication improves diagnosis of implant-related infection . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(3):299–304. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.693019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez E, Cazanave C, Cunningham SA, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Steckelberg JM, Uhl JR, Hanssen AD, Karau MJ, Schmidt SM, Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Mandrekar J, Patel R. Prosthetic joint infection diagnosis using broad-range PCR of biofilms dislodged from knee and hip arthroplasty surfaces using sonication . J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(11):3501–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00834-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ince A, Rupp J, Frommelt L, Katzer A, Gille J, Lohr JF. Is “aseptic” loosening of the prosthetic cup after total hip replacement due to nonculturable bacterial pathogens in patients with low-grade infection? . Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(11):1599–603. doi: 10.1086/425303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner WA, Saleh KJ, Frierson HF. Jr. Reassessment of the usefulness of frozen section analysis for hip and knee joint revisions . Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130(3):363–8. doi: 10.1309/YENJ9X317HDKEXMU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N, Procop GW, Krebs V, Kobayashi H, Bauer TW. Molecular identification of bacteria from aseptically loose implants . Clin Orthop. 2008;466(7):1716–25. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0263-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N, Inaba Y, Choe H, Aoki C, Ike H, Ishida T, Iwamoto N, Yukizawa Y, Saito T. Simultaneous intraoperative detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus and pan-bacterial infection during revision surgery: use of simple DNA release by ultrasonication and real-time polymerase chain reaction . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009;91(12):2896–902. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonner JH, Desai P, Dicesare PE, Steiner G, Zuckerman JD. The reliability of analysis of intraoperative frozen sections for identifying active infection during revision hip or knee arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996;78(10):1553–8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199610000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani BD, Martin DS, Levine MJ, Booth RE, Jr., Tuan RS. The Coventry Award. Polymerase chain reaction detection of bacterial infection in total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 1996;331:11–22. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamae Y, Inaba Y, Kobayashi N, Choe H, Ike H, Momose T, Fujiwara S, Saito T. Quantitative evaluation of periprosthetic infection by real-time polymerase chain reaction: a comparison with conventional methods . Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74(2):125–30. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawietz L, Classen RA, Schroder JH, Dynybil C, Perka C, Skwara A, Neidel J, Gehrke T, Frommelt L, Hansen T, Otto M, Barden B, Aigner T, Stiehl P, Schubert T, Meyer-Scholten C, Konig A, Strobel P, Rader CP, Kirschner S, Lintner F, Ruther W, Bos I, Hendrich C, Kriegsmann J, Krenn V. Proposal for a histopathological consensus classification of the periprosthetic interface membrane . J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(6):591–7. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.027458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, Bauer TW, Springer BD, Della Valle CJ, Garvin KL, Mont MA, Wongworawat MD, Zalavras CG. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection: from the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society . Clin Orthop. 2011;469(11):2992–4. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters RP, de Boer RF, Schuurman T, Gierveld S, Kooistra-Smid M, van Agtmael MA, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Persoons MC, Savelkoul PH. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA load in blood as a marker of infection in patients with community-acquired pneumonia . J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3308–12. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01071-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroh DA, Johnson AJ, Naziri Q, Mont MA. How do frozen and permanent histopathologic diagnoses compare for staged revision after periprosthetic hip infections? . J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(9):1663–8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkin IS, Henry TJ, Fey PI, Iwen PC, Hinrichs SH, Garvin KL. PCR rapidly detects methicillin-resistant staphylococci periprosthetic infection . Clin Orthop. 2003;414:89–94. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000087323.60612.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohtz SW, Muller M, Morawietz L, Winkler T, Perka C. Validity of frozen sections for analysis of periprosthetic loosening membranes . Clin Orthop. 2010;468(3):762–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1102-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaras G, Maduka-Ezeh A, Inwards CY, Mabry T, Erwin PJ, Murad MH, Montori VM, West CP, Osmon DR, Berbari EF. Utility of intraoperative frozen section histopathology in the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012;94(18):1700–11. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunney MM, Patrick S, Curran MD, Ramage G, Hanna D, Nixon JR, Gorman SP, Davis RI, Anderson N. Detection of prosthetic hip infection at revision arthroplasty by immunofluorescence microscopy and PCR amplification of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene . J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(10):3281–90. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3281-3290.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Lin S, Khalil A, Gaydos C, Nuemberger E, Juan G, Hardick J, Bartlett JG, Auwaerter PG, Rothman RE. Quantitative PCR assay using sputum samples for rapid diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia in adult emergency department patients . J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(7):3221–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3221-3226.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]