Abstract

Background

Numerous papers have been published on the medium- and long-term results of hemiarthroplasties (HAs) after femoral neck fracture in the elderly. We were not aware of any articles that describe the outcome of HA until the patient dies.

Methods

Between 1975 and 1989, 307 bipolar hemiarthroplasties were performed in 302 consecutive patients with a displaced femoral neck facture. Patients with osteoarthritis of the hip, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or senile dementia were not included in the study. All patients were followed annually until they died or until they needed a revision operation.

Results

The mortality rate was 28% after 1 year, and 63% after 5 years. The last patient who did not need a revision operation died in October 2010. Revision operations for aseptic loosening, protrusion, or both had to be performed in 34 patients (16%). A difference in reoperation rate was observed between patients less than 75 years of age (38%) and those who were older (6%).

Interpretation

Apart from age below 75 years, male sex appeared to be predictive of a revision operation. HA is a safe and relatively inexpensive treatment for patients over 75 years of age with a displaced femoral neck fracture.

Whether fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients should be treated with internal fixation, HA, or total hip replacement (THR) should be determined by the degree of fracture displacement, patient’s age, functional demands, and risk profile—such as level of cognitive function and degree of physical fitness (Bhandari et al. 2003, Tidermark 2003, Parker and Gurusamy 2010). Internal fixation is therefore the method of choice in young patients with displaced intracapsular fractures (Parker and Gurusamy 2010) and in very frail elderly patients who are not medically fit for prosthesis surgery (Parker et al. 2002). There appears to be a consensus that unipolar or bipolar HA is the preferred treatment for displaced intracapsular fractures in elderly patients with low functional demands in the absence of RA and osteoarthritis of the hip (Bhandari et al. 2005). However, for the relatively healthy, active, and mentally alert elderly patient, treatment is still controversial (Bhandari et al. 2005, Iorio et al. 2006). Reported advantages of HA over THR are reduced dislocation rates, less complex surgery, shorter operation times, less blood loss, and lower initial costs (Keating et al. 2005, van den Bekerom et al. 2010). Opponents of the HA are of the opinion that the chance of protrusion of the femoral head in the acetabulum and subsequently required revision operation in most cases favors the use of a THR.

Since there have not been any really long-term follow-up studies based on a large cohort to support or reject this conviction, the objective of our study was to report the outcome and to identify predictors of revision in patients with an intracapsular femoral neck fracture who have been treated with HA and followed until death or revision of the HA.

Patients and methods

In this cohort study, which was based on a prospectively collected database created in the framework of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO)/Association for the Study of Internal Fixation (ASIF) documentation, we analyzed the results of patients who sustained a displaced intracapsular femoral neck fracture and who were treated with an HA between 1975 and 1989 at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam. All patients were followed until death or until revision of the arthroplasty. This study therefore used the longest possible follow-up. Annual telephone interviews were conducted for those patients who declined further follow-up visits or who were unable to visit the outpatient clinic. When information could not be obtained from the patient, a first-degree relative or the general practitioner was interviewed. Radiographs of the pelvis and axial hip were obtained at each visit. Final radiographs were analyzed with regard to subsidence of the stem and cup, polyethylene wear, osteoarthritis of the acetabulum, protrusio acetabuli, fractures and fissures, and periarticular calcifications.

Inclusion criteria were a displaced femoral neck fracture, ability to give informed consent, and the absence of contraindications for anesthesia. 6 patients with metastatic disease and suspected pathological fractures were also included. Patients who had been bedridden or bed-chair commuters before trauma were included. Patients with advanced radiographic osteoarthritis or who were showing signs of RA of the fractured hip would be treated with THR at our center. Patients with senile dementia were not eligible for inclusion since it was not possible for them to sign the informed consent document and postoperative evaluation was impossible for obvious practical reasons. Patients showing the start of dementia but who were still capable of providing their physician with the necessary information for adequate hip assessment were included in the study.

All patients were treated with a cemented (Sulfix; Sulzer AG, Winterthur, Switzerland) bipolar curved stem hemiprosthesis (Weber Trunion Bearing Rotation; Allo Pro AG, Sulzer AG) because we thought this would result in less pain and less revisions. We used femoral head components with head sizes that were available in 2-mm increments. Nadroparine (0.3 mL) was used as tromboembolic prophylaxis and cefazoline was administered as postoperative infection prophylaxis. All operations were performed by an anterolateral (Watson-Jones) surgical approach to reduce the dislocation rate. The majority of operations were performed by residents under the supervision of the attending orthopedic or trauma surgeon. Patients were mobilized fully weight bearing under supervision of the physiotherapist, with the aid of 2 crutches as tolerated. The patients were allowed to sit on a high chair immediately after surgery and to abandon the crutches at their own convenience. Our standard postoperative protocol for the prevention of dislocation includes patient education and physiotherapy supervision in activities of daily living. After 6 weeks, the patients were allowed to mobilize without further restriction.

The primary outcome measure was revision rate and the secondary outcome measures were implant-related early and late complications (with special emphasis on protrusion acetabuli rate), and mortality.

The outcome at 1 year was also assessed: pain (scored as no, slight, moderate, or severe pain), mobility (walking distance), and patient satisfaction (no, slight, moderate, or severe impairment). A complication was defined as an unintended and undesirable event or condition following surgery that was harmful to the patient and necessitated adjustment of medical treatment, or that led to permanent harm. Implant-related complications were located in the hip region and were due to the placement of the prosthesis or the surgical approach.

Statistics

Continuous data were checked for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test and described as means (with SD) when there was a normal distribution and as medians (with ranges) when there was not. Categorical data were described as frequencies (with percentages).

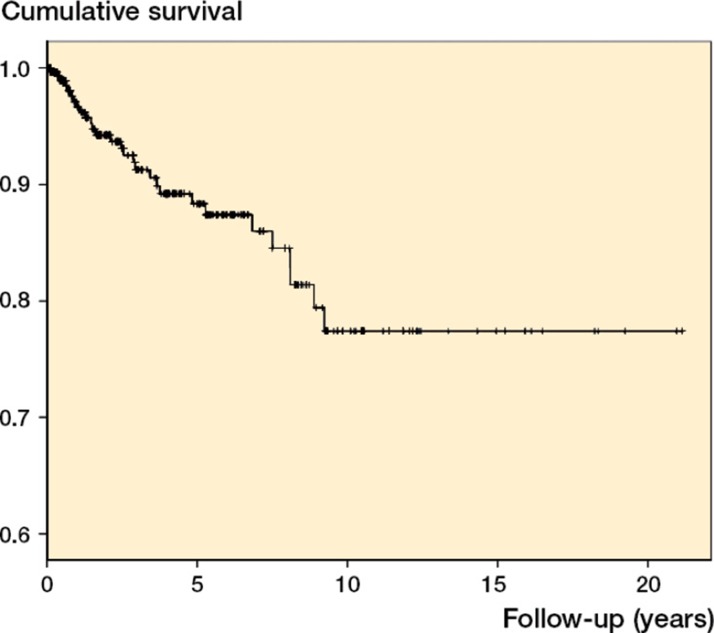

A Kaplan-Meier survival plot was calculated. The endpoint was defined as revision, which included any operation in which any part of the arthroplasty was changed. Deaths without revision were treated as censored data (with censoring at the date of death). Predictors defined were age (below or above 75 years), sex, comorbidities (yes or no), and habitat (living independently or not). Univariate log-rank tests were performed to assess the association between the defined predictors and implant survivorship. In case of significance (significance level 0.1), the factors were entered in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to identify the factors that were significantly related to the risk of requiring revision surgery (significance level 0.05). Hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for these factors.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and the subsequent amendments, and with the laws and regulations of the Netherlands. All patients admitted in 1980 or later gave their informed consent to participate, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (the Medical Ethics Committee) of the Academic Medical Center.

Results

Baseline and intraoperative characteristics

This cohort consisted of 302 patients (237 women (78%) with 307 fractures). Mean age was 80 years (SD 7.9) at the time of trauma. Comorbidities were common (Table 1). The mean interval between admission and operation was 2.3 days (median 0). Most of the patients (193 patients, 63%) were operated on the day of trauma, but 37 patients (12%) were operated 1 day after trauma, 20 patients (7%) were operated after 2 days, and the other 57 patients (19%) were operated at a later time. Secondarily displaced, impacted fractures after initial non-operative treatment were the most common reason for the delay in operative treatment. General anesthesia was applied in 246 patients (80%), and 61 patients (20%) were treated under loco-regional (mainly spinal) anesthesia. Median duration of hospital stay was 17 (2–162) days. Living situation at the time of admission and destinations upon discharge were registered (Table 2).

Table 1.

Preoperative comorbidities

| No. of patients (%) | |

|---|---|

| Senile dementia | 61 (20) |

| Cardiovascular | 68 (22) |

| Neurological | 34 (11) |

| Respiratory | 24 (8) |

| Morbid obesitas | 16 (5) |

| Diabetes (I and II) | 22 (7) |

| Other | 40 (13) |

| Pathological fracture | 6 (2) |

Table 2.

Change of living situation

| Preoperatively (%) | At discharge (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Independently | 50 | 13 |

| Home for elderly | 32 | 34 |

| Nursing home | 14 | 41 |

| Different care facility or hospital | 1 | 7 |

| Unknown | 3 | 0 |

| In-hospital mortality | 0 | 5 |

Outcome at 1-year follow-up

Of the 302 original patients, 87 died during the first year of follow-up and 7 had a revision operation of their HA. 4 revisions were performed because of infection, 2 because of aseptic loosening, and 1 due to persistent instability. Of the 213 patients left, 202 were available for outcome assessment at 1 year. 170 (84%) did not have pain, 19 (9%) experienced slight pain, and 13 (7%) had moderate-to-severe pain.

Only 4% of the patients had an unrestricted walking distance (i.e. not attributable to hip complaints), 18% could walk up to 5 km, 44% could walk 1 km, and 34% could not walk more than 100 meters.

55% of the patients experienced no impairment of their previously sustained femoral neck fracture treated with HA. 38% of the patients were slightly impaired, and 7% described a moderate-to-severe impairment in daily life due to the fracture and subsequent operative treatment.

Revision rate

29 revision operations (9%) had been necessary during follow-up: 5 hips due to a protrusion, 13 hips because of loosening of the prosthesis, 2 hips because of a combination of loosening and protrusion, 1 hip because of penetration of the prosthesis through the cortex, 1 hip because of persistent instability, and 7 hips because of deep infection. Median time from initial operation to revision was 2.2 (0.3–8) years for males and 4.0 (0.1–9) years for females (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survival of hemiarthroplasties.

Univariate analysis showed that lower age (p < 0.001), male sex (p = 0.001), and type of habitat (p = 0.05) were significantly related to an increased risk of revision of the HA. Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified only sex (p = 0.01) and age (p = 0.003) as significant risk factors for revision. HR for age less than than 75 was 3.6 (CI: 1.6–8.2) and HR for male sex was 2.7 (CI: 1.3–5.7).

Early implant-related complications

The overall early complication rate was 17 (6%): 5 hematomas (2%), 10 deep infections (3%), 1 dislocation (0.3%), and 1 penetration of the prosthesis stem (0.3%).

2 patients with a deep infection had no additional operative intervention (a septic protrusion was observed in 1 of these patients), 4 patients had an operative drainage and lavage with intravenous antibiotics postoperatively, and 4 patients required a removal of the arthroplasty due to persistent infection. 1 dislocation of the HA occurred, and this was revised to a THR with acetabular roof reconstruction. A penetration of the femoral cortex was done during primary operation in 1 patient; this patient required a revision of the HA.

Late implant-related complications

The overall late, implant-related, aseptic complication rate (of primary HA) was 37/213 (17%). Overall, there were 12 patients with a protrusion or osteoarthritis of the acetabulum, 20 patients with loosening of the prosthesis, and 5 patients with a combination of both of these. There were more late complications in the younger group than in the older group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Late aseptic complications. Numbers of revisions are shown in square brackets

| Age < 75 (n = 75) |

Age ≥ 75 (n = 138) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | revised | n | (%) | revised | |

| Protrusion | 8 | (11) | [4] | 1 | (1) | [0] |

| Loosening | 14 | (19) | [10] | 6 | (4) | [3] |

| Combination of both | 4 | (5) | [4] | 1 | (1) | [1] |

| Arthrosis | 3 | (4) | [1] | 0 | ||

| Total late complications | 29 | (39) | [19 = 25%] | 8 | (6) | [4 = 3%] a |

p < 0.001

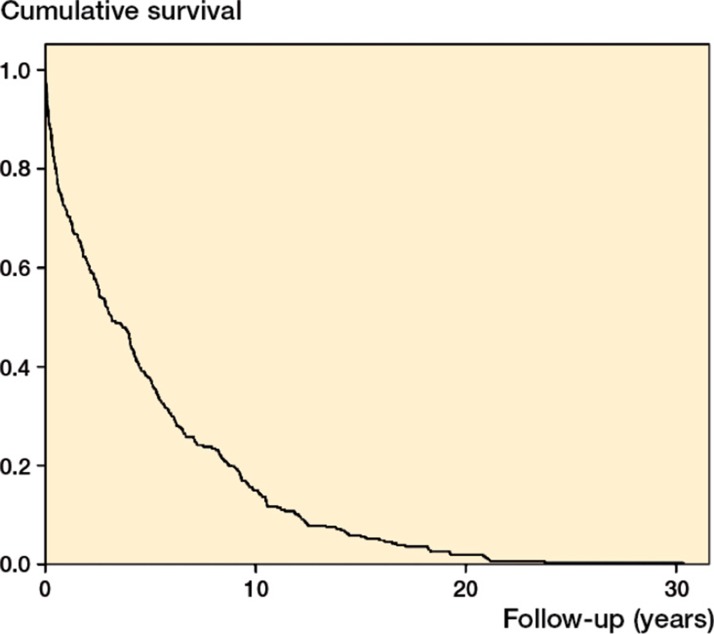

Mortality

All patients were followed until they either died or underwent a revision operation; the median survival time was 3.2 (0–30) years. 12 patients died during their hospital stay, and 15 patients died during the first 30 days. Mortality rates were 28% (87 patients) at 1 year, 39% (120 patients) at 2 years, 49% (151 patients) at 3 years, 54% (167 patients) at 4 years, and 63% (193 patients) at 5 years (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival of patients and hemiarthroplasties.

Discussion

The current study was performed to identify the revision rate and complication rate of HA in a cohort with the longest follow-up possible, and to identify predictors of revision surgery. These rates and predictors are necessary to optimize treatment protocols for these fractures.

Choice of implant

Based on our analyses, we conclude that HA is a suitable treatment option for patients with displaced femoral neck fracture because of the acceptable early aseptic implant-related complication rate (6%) and the acceptable late aseptic implant-related complication rate (17%), with only 12% (36/307) of the patients needing a revision operation.

These favorable findings are in line with the results of a randomized, controlled trial carried out at our institution, comparing HA and THR for acute fractures of the femoral neck in the elderly (van den Bekerom et al. 2010). No significant differences were found in reoperation rate after 5 years. It was concluded that, because of the high percentage of postoperative dislocations (7%) and the higher costs, HA should be the implant of choice. A comparable reoperation rate in HA and THR was also described by Jameson et al. (2013), who gathered data on 3,866 matched pairs of both implants from 41,343 patients, collected in the Hospital Episode Statistics database in the UK. From the Californian Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, data on more than 40,000 patients with an acute femoral neck fracture were extracted: 2,437 THRs and 38,328 HAs. After an 11-year observation period, similar revision risks were found (Soohoo et al. 2013). Although most of the authors of systematic reviews and meta-analyses dealing with this subject have concluded that THR leads to better functional outcomes (Schleicher et al. 2003, Goh et al. 2009, Hopley et al. 2010, Burgers et al. 2012, Liao et al. 2012, Yu et al. 2012, Zi-Sheng et al. 2012) and lower reoperation rates (Hopley et al. 2010, Yu et al. 2012, Zi-Sheng et al. 2012), the high percentage of dislocations after THR continues to be a matter of concern.

The trends in surgical management of femoral neck fractures observed in Sweden (Leonardsson et al. 2012) and the USA (Jain et al. 2008) are interesting. From the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register, it has become clear that “Treatment in Sweden has shifted towards arthroplasties, especially hemiarthroplasties” (Gjertsen et al. 2012). From the Nationwide Inpatient Samples in the USA, data on 162,257 femoral neck fractures were extracted; these had been operated on with osteosynthesis or arthroplasty in the period 1990–2001. The use of HA increased from 68% in the first period (1990–1993) to 75% in the last period (1998–2001). In the same period, the use of THR decreased from 12% to 7%.

Risk of revision

In our study patients who were younger than 75 years of age, male patients had a higher risk of having a revision operation. Like Trueba Davalillo et al. (2010) and Rogmark et al. (2003), we feel that the better functional status of the younger group would explain this different long-term result. One of the few articles that have dealt with this subject analyzed data from the Australian and Italian National Registries, focusing on revision rates in HA and THR, and found that age over 75 was associated with better long-term results of HA (Kannan et al. 2012). Rogmark et al. (2003) used a slightly different protocol: healthy patients between 70 and 80 years of age who were functioning unaided were treated with THR. The remaining patients in this age range and all patients over 80 years of age had an HA. However, the authors concluded that “a differentiated treatment for patients between 70 and 80 years, with THR for the fittest ones and HA for all others, proved to be difficult to accomplish”.

Acetabular erosion

The very low percentage of acetabular erosion/protrusion acetabuli was one of the surprising findings in the present study (4%; 8 hips). Only 4 hips needed revision. It was surprising because acetabular erosion is mentioned as the most important drawback of HA. In the literature, the frequency of acetabular erosion has been reported to range from 0.6% (Haydukewych et al. 2002) to 100% (Avery et al. 2011) after 9–11 years of follow-up. An explanation for these divergent findings cannot be given.

Follow-up

We are not aware of other cohorts with similar (longest possible) follow-up, and comparison with series of THR and other series of HA is difficult. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register reported a 95% survival rate of THR after 5 years for patients with acute femoral neck fractures (Gjertsen et al. 2007). We did not select our patients, but concentrated on a consecutive cohort of patients with displaced femoral neck fracture. Selection bias could be the case in an analysis from an arthroplasty register. Ravikumar and Marsh (2000) performed the study with the longest follow-up, to compare different management options for displaced femoral neck fracture. From 1984 to 1986, 271 patients over 65 years of age with displaced femoral neck fractures were randomized into 1 of 3 treatment groups: internal fixation, hemiarthroplasty, or THR. At 13 years, 24% of the 91 hemiarthroplasty patients had undergone revision surgery, whereas only 7% of all THR patients required additional surgery.

Cemented or uncemented stem

Our hemiarthroplasties used cement fixation. Today, there is evidence that uncemented hemiarthroplasties have an increased risk of revision compared to cemented prostheses (Gjertsen et al. 2012). The increased risk is mainly caused by revisions for periprosthetic fracture, aseptic loosening, hematoma formation, superficial infection, and dislocation (Gjertsen et al. 2012). In a recent randomized trial, this was confirmed and the authors concluded that implant-related complication rates were significantly lower in the group treated with a cemented implant (Taylor et al. 2012).

Surgical approach

The hip was approached anterolaterally in our study. Based on a study from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register on 78,098 THRs, there is evidence that a direct lateral approach lowers the dislocation rate when compared to posterior approaches (Hailer et al. 2012). Enocson et al. (2008) compared the anterolateral approach with the posterolateral approach in patients with femoral neck fractures treated with HA. They concluded that there was a significantly higher risk of dislocation in the posterolateral group.

Acknowledgments

All the authors contributed to interpretation of the data and to revision of the final manuscript. HB and ER contributed to the conception of the study and wrote the study protocol. ER and HB collected data. MB, IS, and ER analyzed the data. IS did the statistical analysis. MB wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

This study could not have been done without the continuous logistical support of the AO Documentation Center, Davos, Switzerland.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Avery PP, Baker RP, Walton MJ, Rooker JC, et al. Total hip replacement and hemiarthroplasty in mobile, independent patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck: a seven- to ten-tear follow-up report of a prospective randomized controlled trial . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93(8):1045–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B8.27132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, et al. Internal fixation compared with arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck: a meta-analysis . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003;85:1673–81. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Tornetta P. 3rd, et al. Operative management of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients: an international survey . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87:2122–30. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgers PT, van Geene AR, van den Bekerom MP, van Lieshout EM, Blom B, Aleem IS, Bhandari M, Poolman RW. Total hip arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures in the healthy elderly: a meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized trials . Int Orthop. 2012;36(8):1549–60. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1569-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enocson A, Tidermark J, Tornkvist H, Lapidus LJ. Dislocation of hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fracture: better outcome after the anterolateral approach in a prospective cohort study on 739 consecutive hips . Acta Orthop. 2008;79(2):211–7. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjertsen JE, Lie SA, Fevang JM, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Vinje T, Furnes O. Total hip replacement after femoral neck fractures in elderly patients: results of 8,577 reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register . Acta Orthop. 2007;78(4):491–7. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjertsen JE, Lie SA, Vinje T, Engesæter LB, Hallan G, Matre K, Furnes O. More re-operations after uncemented than cemented hemiarthroplasty used in the treatment of displaced fractures of the femoral neck: an observational study of 11,116 hemiarthroplasties from a national register . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012;94(8):1113–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B8.29155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh S, Samual M Ching Su D, Chan E, Yeo S. Meta-analysis comparing total hip arthroplasty with hemiarthroplasty in the treatment of displaced neck of the femur fracture . J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(3):4000–6. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidukewych GJ, Israel TA, Berry DJ. Long-term survivorship of cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty for fracture of the femoral neck . Clin Orthop. 2002;403:118–26. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200210000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailer NP, Weiss RJ, Stark A, Kärrholm J. The risk of revision due to dislocation after total hip arthroplasty depends on surgical approach, femoral head size, sex, and primary diagnosis . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):442–8. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.733919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsinki Declaration. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki . http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/ Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects.

- Hopley C, Stengel D Ekkenkamp A, Wich M. Primary total hip arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in older patients: systematic review . BMJ. 2010;340:c2332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio R, Schwartz B, Macaulay W, Teeney SM, Healy WL, York S. Surgical treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly: a survey of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons . J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(8):1124–33. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain NB, Losina E, Ward DM, Harris MB, Katz JN. Trends in surgical management of femoral neck fractures in the United States . Clin Orthop. 2008;466:3116–22. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0392-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson SS, Lees D, James P, Johnson A, Nachtsheim C, McVie JL, Rangan A. Cemented hemiarthroplasty or hip replacement for intracapsular neck of femur fracture? A comparison of 7732 matched patients using national data . Injury. 2013;22(4):S0020-1383(13)00140-X. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.03.021. pii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan A, Kancheria R, McMoahon S, Hawdon G, Soral A, Malhotra R. Arthroplasty options in femoral-neck fracture: answer from the national registries . Int Orthop. 2012;36(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1354-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating JF, Grant A, Masson M, Scott NW, Forbes J F. Displaced intracapsular hip fractures in fit, older people: a randomised comparison of reduction and fixation, bipolar hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty . Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(41):1–65. doi: 10.3310/hta9410. iii-iv, ix-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardsson O, Garellick G, Kärrholm J, Åkesson K, Rogmark C. Changes in implant choice and surgical technique for hemiarthroplasty . 21.343 procedures from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2005–2009;2012;83(1):7–13. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.641104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao L, Zhao JM, Su W, Ding Xf, Luo Sx. A meta-analysis of total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty outcomes for displaced femoral neck fractures . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1 32(7):1021–9. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MJ, Khan RJ, Crawford J, Pryor GA. Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly: a randomised trial of 455 patients . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2002;84:1150–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b8.13522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MJ, Gurusamy K. Arthroplasties (with and without bone cement) for proximal femoral fractures in adults . Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;16(6):CD001706. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001706.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar KJ, Marsh G. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty versus total hip arthroplasty for displaced subcapital fractures of femur–13 year results of a prospective randomised study . Injury. 2000;31(10):793–7. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(00)00125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogmark C, Benoni G, Johnell O, Sernbo I. Results of a new treatment protocol for femoral neck fractures. In: Femoral neck fractures. Aspects on treatment and outcome” . Thesis, University of Lund. 2003.

- Schleicher I, Kordelle J, Jürgensen I, Haas H, Melzer C, Die Schenkelhalsfraktur beim alten Menschen –. Bipolare Hemiendoprothese versus Totalendoprothese . Unfallchir. 2003;106(6):467–71. doi: 10.1007/s00113-003-0597-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SooHoo NF, Farng E, Chambers L, Znigmond DS, Lieberman JR. Comparison of complication rate between hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty for intracapsular hip fractures . Orthopedics. 2013;36(4):384–9. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130327-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor F, Wright M, Zhu M. Hemiarthroplasty of the hip with and without cement: a randomized clinical trial . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012;94(7):577–83. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidermark J. Quality of life and femoral neck fractures . Acta Orthop Scand (Suppl 309) 2003;74:1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueba Davalillo C, Minueza Mejia T, Gil Orbezo F, Ponce Tovar V, Garcia Van den Bekerom MP, Hilverdink EF, Sierevelt IN, Reuling EM, Schnater JM, Bonke H, Goslings JC, van Dijk CN, Raaymakers EL. A comparison of hemiarthroplasty with total hip replacement for displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck: a randomised controlled multicentre trial in patients aged 70 years and over . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(10):1422–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.24899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bekerom MP, Hilverdink EF, Sierevelt IN, Reuling EM, Schnater JM, Bonke H, Goslings JC, van Dijk CN, Raaymakers EL. A comparison of hemiarthroplasty with total hip replacement for displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck: a randomised controlled multicentre trial in patients aged 70 years and over . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(10):1422–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.24899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Wang Y, Chen J. Total hip arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: meta-analysis of randomized trials . Clin Orthop. 2012;470:2235–43. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2293-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zi-Sheng A, You-Zhen J, Zhi-Zhen J, Ting Y. Chang-Quin Z. versus primary total hip arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck in the elderly: a meta-analysis . J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(4):583–90. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]