Abstract

Background and purpose

The risk of atypical fracture of the femur is associated with bisphosphonate use. While characterizing atypical fractures from a previous nationwide study in radiographic detail, we had the impression that the fractures were located either in the subtrochanteric region or in the shaft. We determined whether there is a dichotomy in this respect.

Patients and methods

The distance between the atypical fractures and the lesser trochanter was measured on plain radiographs from 129 of 160 patients with atypical fractures, taken from 2008 through 2010. Analysis of the distances measured showed 2 clusters, which were then analyzed with regard to bisphosphonate use and age.

Results

The distribution of the distances would be best described as 2 clusters, with a dichotomy at 8 cm. The proximal (subtrochanteric) cluster comprised 25 patients who were generally younger (median 71 years) than the 104 patients in the cluster with shaft fractures (median 80 years). The 95% CI for the difference between medians was 4–11 years. Of the patients with subtrochanteric fractures, 18 of 25 used bisphosphonates as compared to 89 of 104 with shaft fractures.

Interpretation

The younger age and possibly smaller proportion of bisphosphonate users in the subtrochanteric cluster may be compatible with a greater influence of mechanical stress in the underlying pathophysiology of proximal fractures.

Atypical fractures of the femur are often described as being mainly located in the subtrochanteric region (Shane et al. 2010). When analyzing the radiographic features of 160 atypical femoral fractures from a nationwide study, we got the impression that the proportion of shaft fractures has been underestimated. However, the unclear definition of what constitutes the subtrochanteric region made it difficult to classify the atypical femoral fractures according to their location. We therefore decided to actually measure where the fracture was located along the shaft, i.e. the distance from the lesser trochanter. By doing so, we noted a somewhat dichotomous distribution of the measured values. We therefore investigated whether the observed distribution of the values would be best described as a combination of two separate Gaussian distributions. This appeared to be the case.

Because the distance from the lesser trochanter showed a dichotomous distribution, the question arose of whether the 2 subgroups are also different in other respects. We therefore determined whether there were differences in age and bisphosphonate use between the subgroups.

Patients and methods

Study population

In a previous publication based on all women above 55 years of age in Sweden in 2008, we identified 51 patients with atypical femoral fractures out of 1,234 women with fractures of the subtrochanteric region or shaft (Schilcher et al. 2011). We then used the same data collection method for 2009 and 2010. Briefly, 3,115 women aged 55 years or more who had a femoral subtrochanteric or shaft fracture (ICD 10 diagnosis codes S722, S723, and M84.3F with external cause code W, i.e. excluding transport accidents) were identified from the National Swedish Patient Register. Digitized radiographs from 3,064 of the 3,114 women (98%) were obtained from the hospitals involved. These radiographs were reviewed together with a re-analysis of the radiographs from 2008. The criteria for atypical fracture were a lateral fracture angle of approximately 90 ± 15 degrees and a visible callus reaction on the initial radiographs (Schilcher et al. 2013). Because these criteria have been refined, the re-analysis of the material from 2008 yielded slightly fewer fractures than the original publication (Schilcher et al. 2011). Altogether, 160 atypical fractures were identified from 2008, 2009, and 2010.

After completion of fracture classification, data on bisphosphonate use were identified from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. Complete linkage between the registers is possible through the use of the personal identity number provided to all Swedish citizens. A full analysis of the fracture risks and their relation to drug use, treatment duration, and comorbidities etc. is ongoing and will be published later.

Permission for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethics Committee without the need for individual patient consent.

Radiographic measurements

All radiographic measurements and classifications were done by VK, who was blind regarding all background information, including drug treatment. Digital DICOM files of plain radiographs of the pelvis, hip, femur, and knee were imported into the database of SECTRA IDS7 Workstation, versions 14.1.0.503 and 12.5.0.264. Measurements were performed using the digital toolbox of this PACS software.

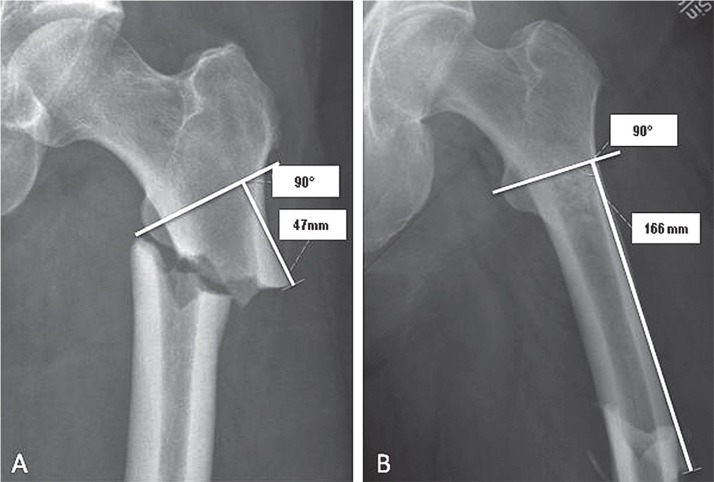

A line perpendicular to the femoral shaft axis was drawn through the most prominent tip of the lesser trochanter. A parallel line was drawn where the fracture met the lateral cortex. The distance between these 2 parallels determined the distance of the fracture from the lesser trochanter (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The distance was measured along the axis of the shaft, from where the fracture meets the lateral cortex to the most prominent tip of the lesser trochanter. A. Fracture of the subtrochanteric region. B. Fracture of the shaft region.

Statistics

Frequency distribution of the measured distances was analyzed using the R program for statistical computing, version 2.15.2, together with the mclust software package for model-based clustering, classification, and density estimation (Fraley and Raftery 2002, Fraley at al. 2012). This uses the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) to choose the best description of the observed variable distribution in terms of a compilation of subgroups.

We then determined whether there were differences in age and bisphosphonate use between the 2 subgroups that emerged from the above analysis, using IBM SPSS Statistics 19. For analysis of age differences, we used Mann-Whitney U test and Hodges-Lehman confidence intervals for differences between medians. For analysis of bisphosphonate use, Fisher’s exact test was used.

Results

Measurements could not be performed in 31 patients, because the fracture was not displayed on the same radiograph as the lesser trochanter, or because flexion of the proximal fragment made it impossible to clearly identify the lesser trochanter. Thus, measurements from 129 of the 160 patients with atypical femoral fractures were analyzed (81%).

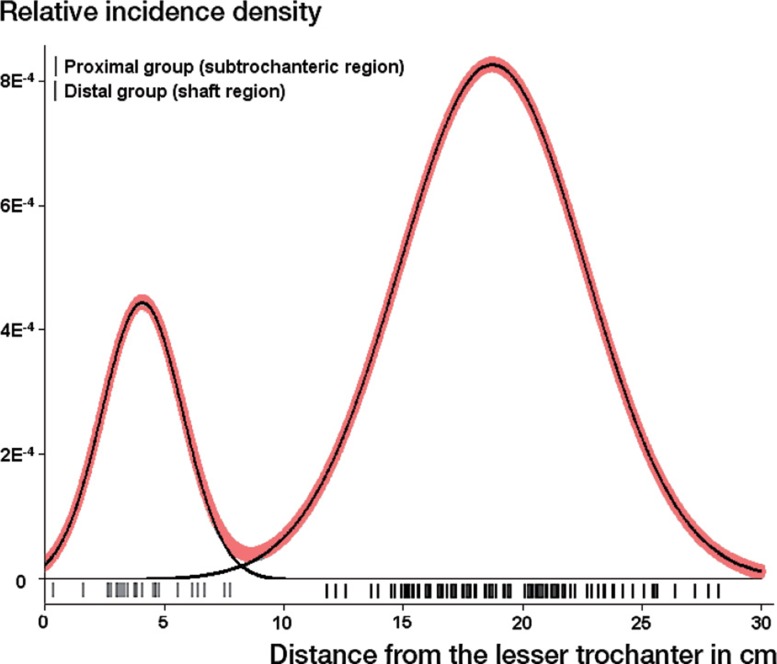

The density distribution for the distances measured showed 2 peaks. The BIC identified an unequal variance model with two components as the best description of the observed data (Figure 2). The proximal subgroup was located at 41 (SD 17) mm and the distal one at 187 (SD 39) mm. The region of uncertainty between the subgroups was narrow, with its center at 80 mm (Supplementary material 1). In our material, no fractures occurred in that region. Thus, it appeared that fractures closer than 8 cm to the lesser trochanter and those further away belonged to 2 distinct subgroups.

Figure 2.

Density plot of the distribution of atypical fractures along the shaft (thick gray line). The distribution can be best described as 2 separate Gaussian distributions. Each fracture is shown as a vertical line above the distance axis.

The subgroup with fractures in the proximal region comprised 25 patients, and the mid-shaft subgroup comprised 104 patients. Patients with proximal fractures had a median age of 71 years (interquartile range 64–79), while the patients with shaft fractures had a median age of 80 years (interquartile range 74–84). The age difference between the group medians was 7 years (95% CI: 4–11).

Bisphosphonate medication was slightly more common in the patients with distal fractures: 18 out of the 25 patients with proximal fractures were bisphosphonate users (72%), while 86 of the 104 patients with shaft fractures (89%) were treated with a bisphosphonate (p = 0.3) (Supplementary material 2).

Discussion

We found a dichotomous distribution of the values for distance between the atypical fracture and the lesser trochanter. The proximal fractures were fewer, were somewhat less related to bisphosphonate use, and occurred in younger patients. These findings possibly suggest a greater influence of mechanical stress in the underlying pathophysiology of proximal fractures.

The ASMBR task force report described atypical fractures as most commonly located in the proximal third of the shaft (Shane et al. 2010). Our findings suggest a different location. A study of 44 patients in Singapore also found a predominantly proximal location of the fractures, without an apparent dichotomy (Koh et al. 2011). The discrepancy between the latter study and our findings might be partly explained by the different criteria used for defining atypical femoral fractures. These authors included fractures with a short oblique configuration, while we abide by a transverse fracture line (Schilcher et al. 2013). Moreover, there may be genetic differences between the mainly Caucasian population in Sweden and the predominantly Asian population in Singapore. Asians are thought to have more curved femora, which might lead to a different mechanical stress distribution.

Atypical femoral fractures occur laterally, where the bone is exposed to tensional stress (Polgár et al. 2003, van der Meulen and Boskey 2012). However, a dichotomous distribution of the fractures along the shaft does not correspond to the distribution of this tensile stress. According to the classical analysis by Koch (1917), the highest tensile stress is located in the lateral side of the subtrochanteric region and remains on a rather high level further down into the mid-shaft, where it rapidly decreases (Supplementary material 3). These historic computations are confirmed by modern finite-element models, which show a maximum tensile strain in the subtrochanteric region under static conditions (Polgár et al. 2003, Phillips 2009), as well as during walking or stair climbing (Speirs et al. 2007). The distribution of tensile strain suggests that fractures could be expected to be more proximal when mechanical factors dominate in the pathogenesis. This could be related to the slightly weaker association of proximal fractures with bisphosphonate use and younger age.

Cortical thickness of the shaft decreases with age (Koeppen et al. 2012). This might be related to the higher age of the patients with distal fractures in our study.

The definition of “subtrochanteric” is problematic. There are at least 15 different classification methods for subtrochanteric femoral fractures in the literature (Loizou et al. 2010). The positive predictive value in identifying a subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femoral fracture through the medical record coding may be as low as 36% (Spangler et al. 2011). According to the AO classification system, subtrochanteric fractures are a subcategory of diaphyseal fractures, occurring within 3 cm below the lesser trochanter (Müller et al. 1990). Nevertheless, in the literature, subtrochanteric fractures are often defined as occurring within 5 cm below the lesser trochanter. The dichotomy we found suggests that for atypical fractures, there may be a natural border of some kind as far down as 8 cm.

Our study had several limitations. Our findings are observational, and can only hint at possible causative relationships. It might be more difficult to identify an atypical femoral fracture in the subtrochanteric region than in the shaft. Because of the shape of the cortical contour, it becomes difficult to distinguish a small callus reaction there. Furthermore, when the proximal fragment is small, the hip is often flexed on the initial radiographs, making the typical appearance of atypical fractures less obvious. It is therefore possible that the atypical femoral fractures of the subtrochanteric region are under-represented. Our study was restricted to a female Caucasian population from a Nordic country. Also, we did not assess the duration of bisphosphonate therapy in the patients. The measurements were performed on uncalibrated plain radiographs, leading to low comparability between cases, and disregarding the complex three-dimensional architecture.

Due to the algorithm used to identify patients in the National Register, only the first femoral fracture that occurred during the period 2008–2010 was studied. Thus, we lack information on bilateral fractures. On the other hand, this means that we avoid the statistical problem of having dependent data points.

There are several causes for debate regarding the risk of atypical fractures, contributing factors, timing of treatment, and location of other locations of tensional stress outside the femur (Bjørgul and Reigstad 2011, Puan and Tan 2011, Meier 2012, Rydholm 2012).

In conclusion, 129 atypical femoral fractures showed a dichotomous distribution that may represent 2 different subgroups: atypical shaft fractures and the less common atypical subtrochanteric fractures. The differences in age and possibly bisphosphonate use indicate that subtrochanteric fractures may be more related to mechanical loading,

Acknowledgments

VK contributed to the evaluation of radiographs, analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting of the article. JS collected all the radiographs and helped revise the article. PA contributed to interpretation of the data, and to drafting and revision of the article.

We thank Thomas Annerholm for his technical support using the PACS and Philippe Wagner for helping us to get started with R. The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council (VR 02031-47-5), Linköping University, Östergötland County Council, and the King Gustaf V and Queen Victoria Free Mason Foundation.

PA has a patent on a process for coating metal implants with bisphosphonates, and has shares in a company that is trying to commercialize the principle (Addbio AB). PA has also received consulting reimbursement and grants from Eli Lilly & Co. VK and JS have no competing interests to declare.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material 1–3: see www.actaorthop.org, identification number 6660.

References

- Bjørgul K, Reigstad A. Atypical fracture of the ulna associated with alendronate use—a case report . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(6):761–3. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.636676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley C, Raftery AE. Model-based clustering, discriminant analysis and density estimation . J Am Stat Ass. 2002;97:611–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley C, Raftery AE, Murphy TB, Scrucca L. mclust Version 4 for R: Normal Mixture Modeling for Model-Based Clustering, Classification, and Density Estimation: Technical Report No. 597 . Washington: Department of Statistics, University of Washington. 2012.

- Koch JC. The laws of bone architecture . Am J Anat. 1917;21(2):177–298. [Google Scholar]

- Koeppen VA, Schilcher J, Aspenberg P. Atypical fractures do not have a thicker cortex . Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(12):2893–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J SB, Goh SK, Png MA, Ng A CM, Howe TS. Distribution of atypical fractures and cortical stress lesions in the femur: implications on pathophysiology . Singapore Med J. 2011;52(2):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loizou CL, McNamara I, Ahmed K, Pryor GA, Parker MJ. Classification of subtrochanteric femoral fractures . Injury. 2010;41(7):739–45. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier R PH, Lorenzini KI, Uebelhart B, Stern R, Peter RE, Rizzoli R. Atypical femoral fracture following bisphosphonate treatment in a woman with osteogenesis imperfecta—a case report . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):548–50. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.729183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, Schatzker JL. The Comprehensive Classification of Fractures of Long Bones . Berlin Heidelberg New York: Spinger Verlag. 1990.

- Phillips A TM. The femur as a musculo-skeletal construct: a free boundary condition modelling approach . Med Eng Phys. 2009;31(6):673–80. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polgár K, Gill HS, Viceconti M, Murray DW, O’Connor JJ. Strain distribution within the human femur due to physiological and simplified loading: finite element analysis using the muscle standardized femur model . Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2003;217(3):173–89. doi: 10.1243/095441103765212677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pua KL, Tan MH. Bisphosphonate-associated atypical fracture of the femur: Spontaneous healing with drug holiday and re-appearance after resumed drug therapy with bilateral simultaneous displaced fractures—a case report . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(3):380–2. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.581267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydholm A. Highly different risk estimates for atypical femoral fracture with use of bisphosphonates—debate must be allowed . Acta Orthop. 2012;86(4):319–20. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.718517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilcher J, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft . N Engl J Med. 2011;364(18):1728–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilcher J, Koeppen V, Ranstam J, Skripitz R, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Atypical femoral fractures are a separate entity, characterized by highly specific radiographic features. A comparison of 59 cases and 218 controls . Bone. 2013;52(1):389–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shane E, Burr D, Ebeling PR, Abrahamsen B, Adler RA, Brown TD, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research . J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(11):2267–94. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler L, Ott SM, Scholes D. Utility of automated data in identifying femoral shaft and subtrochanteric (diaphyseal) fractures . Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(9):2523–7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1476-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speirs AD, Heller MO, Duda GN, Taylor WR. Physiologically based boundary conditions in finite element modelling . J Biomech. 2007;40(10):2318–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meulen MC, Boskey AL. Atypical subtrochanteric femoral shaft fractures: role for mechanics and bone quality . Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(4):220. doi: 10.1186/ar4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.