Abstract

Background and purpose

Degenerating cartilage releases potential danger signals that react with Toll-like receptor (TLR) type danger receptors. We investigated the presence and regulation of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR9 in human chondrocytes.

Methods

We studied TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 mRNA (qRT-PCR) and receptor proteins (by immunostaining) in primary mature healthy chondrocytes, developing chondrocytes, and degenerated chondrocytes in osteoarthritis (OA) tissue sections of different OARSI grades. Effects of a danger signal and of a pro-inflammatory cytokine on TLRs were also studied.

Results

In primary 2D-chondrocytes, TLR1 and TLR2 were strongly expressed. Stimulation of 2D and 3D chondrocytes with a TLR1/2-specific danger signal increased expression of TLR1 mRNA 1.3- to 1.8-fold, TLR2 mRNA 2.6- to 2.8-fold, and TNF-α mRNA 4.5- to 9-fold. On the other hand, TNF-α increased TLR1 mRNA] expression 16-fold, TLR2 mRNA expression 143- to 201-fold, and TNF-α mRNA expression 131- to 265-fold. TLR4 and TLR9 mRNA expression was not upregulated. There was a correlation between worsening of OA and increased TLR immunostaining in the superficial and middle cartilage zones, while chondrocytes assumed a CD166× progenitor phenotype. Correspondingly, TLR expression was high soon after differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells to chondrocytes. With maturation, it declined (TLR2, TLR9).

Interpretation

Mature chondrocytes express TLR1 and TLR2 and may react to cartilage matrix/chondrocyte-derived danger signals or degradation products. This leads to synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which stimulate further TLR and cytokine expression, establishing a vicious circle. This suggests that OA can act as an autoinflammatory disease and links the old mechanical wear-and-tear concept with modern biochemical views of OA. These findings suggest that the chondrocyte itself is the earliest and most important inflammatory cell in OA.

In vascular tissue, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) have important roles in activation of the innate and adaptive host defense against infections, by recognizing a specific but restricted set of patterns of microbial origin (so-called pathogen- or microbe-associated molecular patterns or PAMPs/MAMPs). So far, 10 functional TLRs have been identified in humans (TLR1–TLR10). TLR2 can form homodimers and heterodimers with TLR1 or TLR6 (Ozinsky et al. 2000), whereas the other TLRs form homodimers (Takeda 2005, Lee et al. 2012). Cell surface TLRs such as TLR1, TRL2, TLR4, and TLR6 recognize molecular patterns exposed on the surface of microbes to allow immediate ligand-receptor interactions. Endosomal TLRs such as TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 recognize nucleic acids (RNA and/or DNA) exposed first after partial degradation of the microbes. TLRs are expressed differentially in different tissues and cells (Garrafa et al. 2011), which may in part explain some tissue-specific features of the host response to our microbiome.

TLRs can also bind to various damage-associated molecular patterns, which are endogenous danger signals or alarmins (Bianchi 2007). This can lead to autoinflammatory conditions, but it also contributes to production of co-stimulatory signals necessary for adaptive immune reactions. Chondrocyte-derived high-mobility group box 1, heat-shock proteins, and several components of the cartilage extracellular matrix (ECM)—e.g. low-molecular-weight hyaluronan, heparan sulphate, biglycan, and fibronectin fragments—have been identified as potential TLR ligands (Scanzello et al. 2008, Chang 2010, Erridge 2010, Hodgkinson and Ye 2011). From this point of view, OA could be considered as an autoinflammatory disease with the chondrocyte as its primary inflammatory cell, as suggested in a recent editorial (Konttinen et al. 2012).

Reports on chondrocyte TLRs have been quite scarce and somewhat controversial. There is consensus regarding TLR2 (Liu-Bryan et al. 2005, Su et al. 2005, Kim et al. 2006, Liu-Bryan et al. 2010), whereas TLR1 (Liu-Bryan et al. 2005, Su et al. 2005) and TLR9 (Liu-Bryan et al. 2005, Bobacz et al. 2007) has been claimed to be present or absent. We studied these 3 TLRs in the current work. TLRs are differentially expressed in human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) (Raicevic et al. 2011) and are regulated by inflammatory stimuli (Romieu-Mourez et al. 2009). MSC-like progenitors have also been described in OA cartilage, although their origin is still unclear (Koelling et al. 2009, Pretzel et al. 2011).

We studied the expression of some of the key TLRs mentioned above in primary chondrocyte isolates in 2D cultures, MSCs in 3D pellets undergoing chondrogenesis, and chondrocytes in situ in OA tissue sections representing different OARSI (Osteoarthritis Research Society International) grades (Pritzker et al. 2006). Their inflammatory regulation in 3D pellets was studied using a TLR1/2-specific ligand and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and compared to different OARSI grades of OA. Chondroprogenitor and hematopoietic markers were also studied in different grades of OA.

Patients and methods

Primary chondrocyte isolation and cultures

This study was approved by the local ethical committee (Dnro HUS 37/E6/04). After obtaining informed patient consent, primary chondrocytes were isolated as described earlier (Brittberg et al. 1994, 2001) from femoral heads from 4 femoral neck fracture arthroplasty patients (see Supplementary material).

hMSC isolation and chondrogenic cultures

Establishment of hMSC lines was approved by the institutional review board. 4 primary MSC lines were established from healthy adult donors as described earlier (Supplementary material; Sillat et al. 2009). For chondrogenesis experiments, passage 3–4 cells were washed twice in chondrogenic induction medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) using centrifugation at 150 × g for 5 min and resuspension. Washed cells were transferred to medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL TGF-β3 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), divided to 2.5 × 105 cells per tube, and centrifuged at 150 × g for 5 min. Pellets were cultured in polypropylene tubes at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. The medium was replaced every 3 days. Differentiation of the cells in the pellets was studied at days 0, 7, 14, and 21.

Stimulation with Pam3CSK4 and TNF-α

Primary chondrocyte isolates (n = 4) and day 21 chondrogenic pellets (n = 4) were used for stimulation experiments. Cells were placed in regular culture medium and stimulated for 12 h with 0.5 μg/mL Pam 3CSK4 (Invivogen, San Diego, CA) or with 5 ng/mL and 100 ng/mL rhTNF-α (R&D Systems).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

The mRNA levels of SOX9, COL2A1, TNF-α, TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, and β-actin were analyzed using qRT-PCR as described in Supplementary material.

Immunostaining of TLRs in chondrogenic cultures

Sections of pellets of MSCs induced into chondrogenesis were stained for TLR1, TLR2, TLR9, collagen type II, and COL2A-3/4M (collagenase-cleaved type II collagen) using avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex methods as described in Supplementary material.

Safranin O staining and OARSI grading of OA tissue samples

This study was approved by the local ethical committee (Dnro HUS 165/E6/03). Osteochondral cylinder samples were harvested from tibial plateau specimens obtained from knee joints of 14 patients (10 female and 4 male), and were stained using Safranin T and toluidine blue and graded according to OARSI (Pritzker et al. 2006) as described in Supplementary material.

Immunohistochemical staining of different OARSI-grade OA cartilage tissue sections

Representative samples from all the different OARSI grades were stained immunohistochemically for TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9; TNF-α; CD166 and CD105 (MSC markers), and CD34 and CD31 (hematopoietic stem cell markers) as described in Supplementary material.

Statistics

The qRT-PCR data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and unpaired Student’s t-test. Immunostaining data were analyzed using Kruskal one-way variance test to compare the differences in the proportions of TLR+ or CD166+ cells in different OA grades (from 1 to 5) and between different cartilage zones (superficial, middle, and deep). Mann-Whitney U-test was used for pairwise comparison of TLR-specific differences between cartilage zones and different OARSI grades. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare TLRs between the 3 different cartilage zones, separately for each different OARSI grade (e.g. grade-1 samples, grade-2 samples etc.). Non-parametric tests were used since the data had ordinal levels of measurement. We used SPSS software version 18.0 for Windows.

Results

TLR1, TLR2, and TLR9 mRNA expression in primary chondrocytes

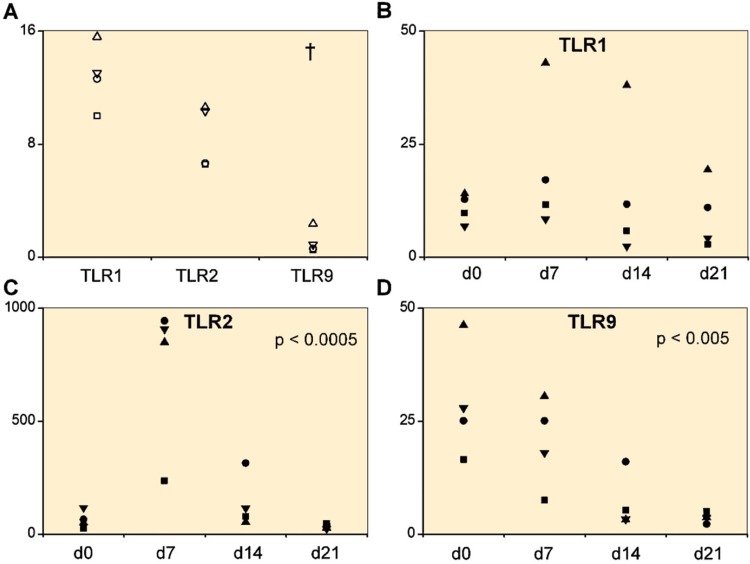

TLR mRNAs were first studied in primary 2D cultures of isolated mature hyaline articular cartilage chondrocytes from trauma patients. TLR profiling disclosed relatively high levels of TLR1 and TLR2 mRNA compared to TLR9 mRNA levels (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

A. Toll-like receptors TLR1, TLR2, and TLR9 in 4 primary chondrocyte isolates. B–D. 4 mesenchymal stem cell lines (day 0) differentiating via a progenitor stage (days 7 and 14) to chondrocytes (day 21). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was used to measure the mRNA copy numbers per 106 β-actin copies. In primary chondrocyte isolates, TLR1 and TLR2 mRNA levels were higher than TLR9 mRNA levels († p < 0.001). Overall changes in TLR2 and TLR9 mRNA expression were significant during chondrogenesis.

TLR1, TLR2, and TLR9 expression during chondrogenesis

As even in trauma patients the primary chondrocytes may already have been exposed to inflammatory cytokines, we wanted to monitor TLR mRNA expression in de novo generated chondrocytes and to follow how this changed during differentiation. TLR1 mRNA increased slightly from MSCs to day 7 chondrocyte progenitors, but declined thereafter (p = 0.6) (Figure 1B). TLR2 mRNA increased 11.4-fold from day 0 (MSCs) to day 7 (chondrocyte progenitors) and then progressively declined at days 14 and 21 (p < 0.001) (Figure 1C). TLR9 mRNA was highest in day 0 MSCs and then progressively diminished (p = 0.004) (Figure 1D).

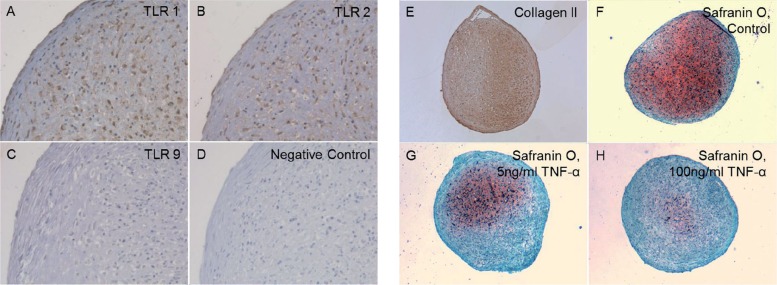

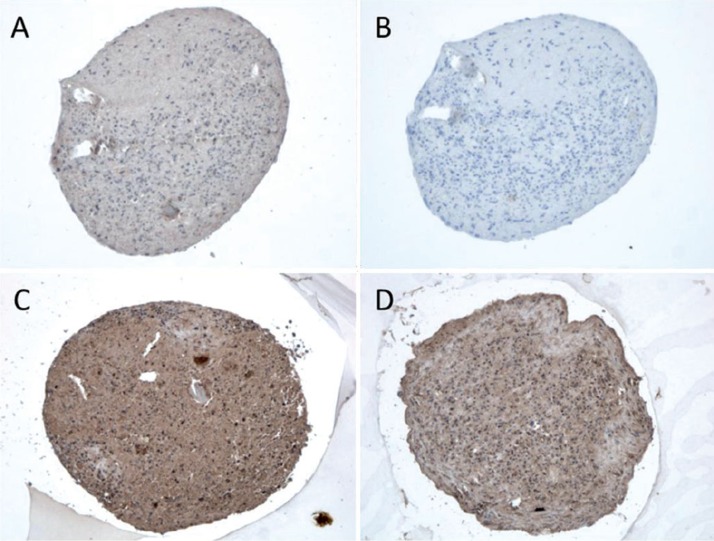

After 21 days of differentiation, the pellets from all 4 patients showed an increase in the expression of chondrogenic markers with a mean 9-fold (SD 7) increase in Sox9 mRNA expression and a 571-fold (SD 922) increase in Col2A1 mRNA expression relative to the controls (hMSC pellets kept for 21 days in regular medium). Differentiated day 21 pellets also stained positively for collagen type II and proteoglycans (Figure 2E, F). Chondrocytes in the 3D-pellets stained for TLR1 (Figure 2A) and TLR2 (Figure 2B), but not for TLR9 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Chondrocyte pellets at day 21 produced from human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. A–D. Immunostaining of TLR1 (panel A), TLR2 (panel B), and TLR9 (panel C) compared to negative staining control (panel D). Magnification 200×. E–G. Collagen type-II immunostaining (Collagen II, panel E) and Safranin O staining of untreated 3D chondrocyte pellets (control, panel F) compared to pellets treated with 5 ng/mL TNF-α (panel G) and 100 ng/mL TNF-α (panel H) (showing dose-dependent depletion of proteoglycans in the presence of TNF-α). Magnification 100×.

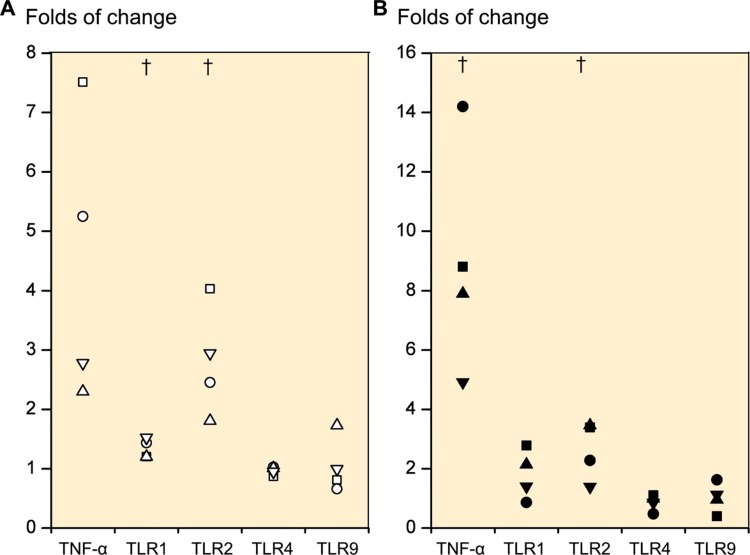

TLR1/2-specific stimulation of chondrocytes

In order to determine whether TLR1 and 2 receptors are functional, the cells were stimulated with the synthetic TLR1/2 ligand Pam3CSK4. In 2D cultured primary chondrocytes (n = 4) and day-21 3D chondrogenic chondrocyte pellets (n = 4), the TLR1/2 ligand caused a 4.5-fold (p = 0.06) and a 9.0-fold (p = 0.03) increase in TNF-α mRNA, respectively (Figure 3). Correspondingly, TLR1 mRNA expression increased 1.3-fold (p = 0.03) and 1.8-fold (p = 0.2). TLR2 mRNA increased 2.8-fold (p = 0.03) and 2.6-fold (p = 0.05). In comparison, the expression levels of TLR4 and TLR9 mRNA remained stable, with TLR4 showing 1.0-fold (p = 0.4) and 0.9-fold (p = 0.4) differences and TLR9 showing 1.1-fold (p = 0.8) and 1.0-fold (p = 0.9) differences.

Figure 3.

Folds of change in tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) expression and TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 expression upon stimulation with TLR 1/2-specific ligand Pam 3CSK4. Primary 2D chondrocyte cultures (A) and 3D chondrocyte pellet cultures (B) at day 21 (i.e. produced from human mesenchymal stem cells at day 21). † p ≤ 0.05 compared to unstimulated cultures.

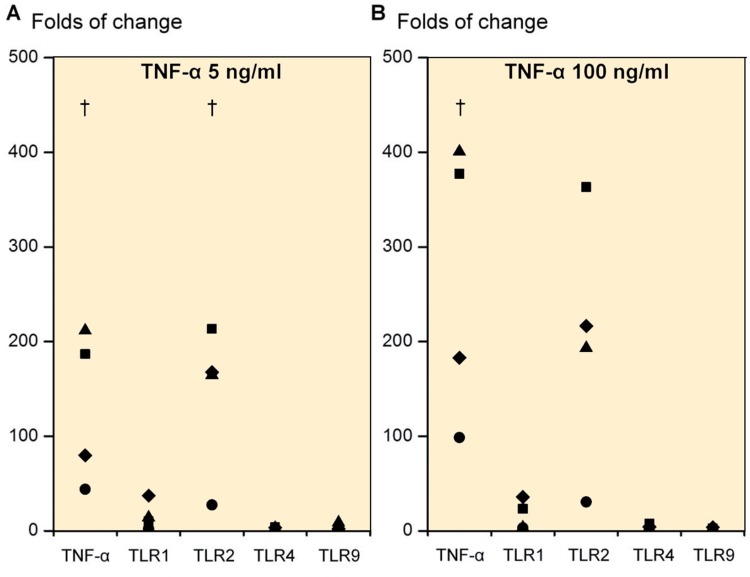

TNF-α stimulation of chondrocytes

Due to the substantial increase in TNF-α mRNA expression from TLR1/2-mediated danger signal stimulation, we also studied the effects of TNF-α on TLRs. Day-21 3D chondrogenic chondrocyte pellets (n = 4) stimulated with 5 ng/mL rhTNF-α caused a 130.6-fold increase in TNF-α mRNA (p = 0.049), a 16-fold increase in TLR1 mRNA (p = 0.1), a 143-fold increase in TLR2 mRNA (p = 0.04) and only a 2.6-fold increase in TLR4 mRNA (p = 0.1) and a 3.2-fold increase in TLR9 mRNA (p = 0.3) compared to pellets cultured in the absence of rhTNF-α (Figure 4). A TNF-α dose of 100 ng/mL increased the TNF-α mRNA expression 265-fold (p = 0.04), TLR1 mRNA expression 16-fold (p = 0.1), TLR2 mRNA 201-fold (p = 0.06), TLR4 mRNA 3.6-fold (p = 0.2) and TLR9 mRNA expression 2.2-fold (p = 0.2) compared to unstimulated cultures (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Folds of change in tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 upon stimulation of primary 3D chondrocyte pellet cultures. Stimulation with 5 ng/mL TNF-α (A) and with 100 ng/mL TNF-α (B). † p ≤ 0.05. All statistical comparisons were against unstimulated cultures (normalized to 1).

TNF-α used at 0, 5, and 100 ng/mL also caused a dose-dependent loss of proteoglycans in day-21 chondrocyte pellets (Figure 2F–H). Immunostaining of day-21 3D chondrogenic chondrocyte pellets for collagenase-cleaved COL2A-3/4M neoepitope was increased with TNF-α stimulation, but was more intense after treatment with 5 ng/mL than 100 ng/mL TNF-α (Figure 5C and D). Immunostaining of collagenase-cleaved COL2A-3/4M neoepitope was seen in chondrocytes and ECM. Immunostaining of unstimulated day-21 3D chondrogenic chondrocyte pellets with collagenase-cleaved COL2A-3/4M neoepitope was weak (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Collagenase-cleaved COL2A-3/4M neoepitope immunostaining of 3D chondrocyte pellets. Untreated 3D-chondrocyte pellets (A) and the negative staining control (B). 3D chondrocyte pellets stimulated with 5 ng/mL TNF-α (C) and 100 ng/mL TNF-α (D). Magnification 100×.

Chondrocyte progenitor markers and TLRs in different OARSI-grade OA samples

Chondroprogenitor cells have been reported to be present in healthy human articular cartilage and in late OA cartilage (Koelling et al. 2009, Pretzel et al. 2011). However, the possible relationship between progenitor markers and OA grade has not been studied before. The MSC marker CD105 was only slightly increased in the higher OARSI-grade OA samples (the proportion of positive cells remaining was always <20%; data not shown). In contrast, the proportion of CD166+ cells increased with increasing OARSI grade in the surface and middle zones (p = 0.005 and p = 0.001) (Table and Supplementary figure). All cells in the cartilage were negative for hematopoietic cell lineage markers CD31 and CD34 (data not shown).

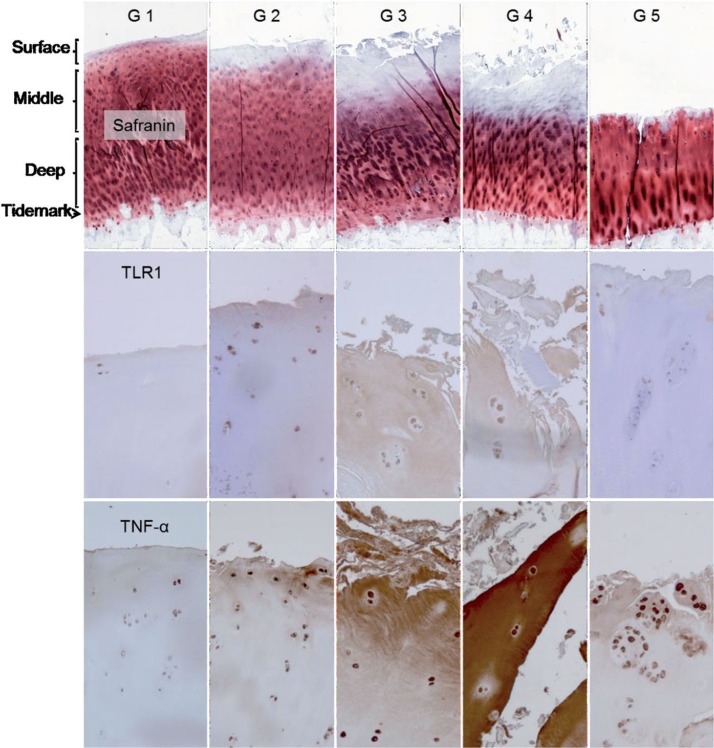

In grade-1 OA samples, TLR1+ chondrocytes were confined to the surface zone. With increasing degeneration, TLR1 immunostaining became more intense, the proportion of TLR1+ chondrocytes increased in the surface zone, and TLR1+ cells also appeared in the middle and even in the deep zone. In OARSI grade-3 and -4 OA samples, some TLR1-specific staining was also seen in the ECM (Figure 6, lower row). A similar specific staining pattern was seen for TLR2 and TLR9 (see Supplementary figure).

Figure 6.

Safranin O, TLR1, and TNF-α staining of OARSI-graded osteoarthritis samples (grades G1–G5). TLR2 and TLR9 immunostaining was rather similar to that of TLR1 and is shown in Supplementary figure. Surface (tangential, gliding), middle (transient), and deep (radial) zones are marked, and also tide mark (between cartilage and calcified cartilage) and subchondral bone. The safranin O microphotographs are panoramic images, constructed from several microphotographs to provide an overall view of all zones in one image. Magnification 100×.

All TLRs showed a similar pattern in histomorphometry (Table; TLR9 data not shown). The proportion of positively stained cells increased in the surface and middle zones with progression of OA to grades 3 and 4 (p < 0.01 except for TLR2 in the surface zone: p = 0.01). In grade-5 OA samples, the surface zone was totally worn off and the percentage values of TLR+ chondrocytes in the remaining middle zone were low (Table).

Discussion

Cartilage is subjected to considerable mechanical impact, compression, tensile and shear loading. Due to the lack of blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves, hyaline articular cartilage has a poor capacity for repair (van Osch et al. 2009). Cartilage cannot readily recruit circulating MSCs, but is dependent on the repair capacity of the sessile mature chondrocytes and chondrocyte progenitors (Koelling et al. 2009, Grogan et al. 2009). The lack of a convective transit compartment (i.e. vessels) means that repair is confined to the pericellular and the nearby intraterritorial cartilage matrix area. As the cartilage degenerates, matrix molecules are released—perhaps in partially degraded and denatured form—and can act as danger signals that bind to danger signal receptors (Erridge et al. 2010). The present study shows conclusively that non-OA chondrocytes and chondrocytes generated from MSCs express TLR1, TLR2, and somewhat less TLR9, at the mRNA and/or protein level. Our findings also suggest that the TLR profile is highly dependent on the activation and differentiation state of the chondroid cells, with for example TLR9 being mainly present in inflamed (OA) chondrocytes and progenitors, but being scanty in mature, resting chondrocytes. This may explain the apparent discrepancies mentioned in the Introduction (Liu-Bryan et al. 2005, Su et al. 2005, Bobacz et al. 2007).

Histomorphometric evaluation of progenitor cell marker CD166 and Toll-like receptors 1 (TLR1), 2 (TLR2), and 4 (TLR4) in OARSI-graded grade 1–5 osteoarthritis (OA) samples. Proportions of positively stained cells (%) in the surface (S), middle (M), and deep zones (D) are given. Because the surface zone was totally worn off in all G5 OA samples, no value is given for this zone in grade-5 OA samples. Mean and SD

| G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | M | D | S | M | D | S | M | D | S | M | D | S | M | D | |

| CD 166 | 51 | 0 | 0 | 81 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 46 | 0 | 97 | 72 | 0 | – | 35 | 0 |

| (17) | (7) | (8) | (19) | (6) | (8) | (6) | |||||||||

| TLR 1 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 82 | 22 | 0 | 96 | 64 | 14 | 96 | 74 | 0 | – | 16 | 0 |

| (1) | (12) | (6) | (4) | (7) | (2) | (7) | (8) | (6) | |||||||

| TLR 2 | 30 | 5 | 2 | 80 | 23 | 2 | 96 | 48 | 12 | 96 | 60 | 0 | – | 14 | 0 |

| (6) | (3) | (0) | (12) | (7) | (3) | (4) | (14) | (11) | (6) | (5) | (10) | ||||

| TLR4 | 24 | 4 | 0 | 94 | 44 | 6 | 95 | 59 | 0 | 97 | 45 | 0 | – | 29 | 0 |

| (5) | (4) | (6) | (8) | (3) | (6) | (12) | (5) | (8) | (23) | ||||||

| TLR9 | 44 | 7 | 0 | 98 | 38 | 24 | 96 | 61 | 0 | 87 | 34 | 0 | – | 23 | 0 |

| (6) | (13) | (2) | (27) | (5) | (5) | (11) | (7) | (13) | (10) | ||||||

OARSI: Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

Given the lack of blood and lymphatic vessels, endogenous cartilage matrix-derived danger signals (alarmins) are not washed away from the cartilage (Heinegård and Saxne 2011). The undiluted danger signals can therefore reach high concentrations in chondrocyte lacunae. Chondrocytes in lacunae are equipped with danger signal receptors of TLR-type and can be stimulated by locally produced matrix-derived TLR ligands (for a table of endogenous danger signals, see Konttinen et al. 2012). TLR profiling of the cartilage revealed TLR1 and TLR2, which can also form TLR1/2 heterodimers (Ozinsky et al. 2000). Because these are the prominent chondrocyte TLRs, we used Pam3CSK4 for stimulation of 2D primary chondrocytes and 3D chondrocyte pellets. These experiments disclosed 2 interesting things. First, they confirmed the presence of TLR1 and TLR2 on human chondrocytes, by showing that the TLR1/2 receptor is also functionally active. More importantly, danger signal-TLR1/2 interaction led to a substantial production of pro-inflammatory TNF-α. At the same time, danger signal-TLR1/2 interaction led to a more or less significant upregulation of TLR1 and TLR2 mRNA, without affecting TLR9. These findings suggest that TLRs in chondrocytes are actively engaged and differentially regulated in the inflammatory process.

Due to a substantial increase in TNF-α by danger signal stimulation of TLR1/2, its effects on chondrocytes could be studied. Again, we made 2 interesting observations. TNF-α treatment increased TLR1 and TLR2 mRNA expression more or less significantly, which could increase TLR1/2 receptor expression. Although TLR2 mRNA expression increased much more than TLR1 mRNA expression, the starting values for TLR1 mRNA were higher than those for TLR2 mRNA. Furthermore, TLR2 also forms TLR2/2 homodimers and TLR2/TLR6 heterodimers (Ozinsky et al. 2000), which may consume surplus TLR2. Secondly, at physiological and supraphysiological concentrations, TNF-α increased its own production in chondrocytes 131- to 264-fold in a dose-dependent manner. A possible self-amplifying loop emerges: danger signal stimulation upregulates TNF-α and TLR1/2 expression, and conversely TNF-α upregulates TLR1/2 expression and also its own production. One of the key conclusions of our work is that chondrocytes might be involved already at the early stages of OA.

TNF-α-stimulation caused dose-dependent proteoglycan depletion. In line with this result, COL2A-3/4M immunostaining showed an increase in type-II collagen in 3D chondrocyte pellets stimulated with TNF-α. Such a pattern seems to be in agreement with other studies that have demonstrated a correlation between aggrecan and collagen degradation (Squires et al. 2003). These results show that chondrocytes can mount an inflammatory response, which might be sufficient to compromise the integrity of native proteoglycans and collagen ECM.

We then studied the expression of TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 by chondrocytes in OA samples, using the histological OARSI grading as the reference of disease severity. TLR1, TLR2, and TLR4—but also TLR9—increased with progression of OA until grade 3–4, but then all TLRs declined so that a bell-shaped curve emerged. Upregulation of TLRs was first seen in the surface zone and later in the middle zone, and even in the deep zone. Earlier studies have emphasized the role of TLR4 in osteoarthritis, but our results show that TLRs other than TLR4 also become upregulated in OA and may participate in OA pathogenesis.

The present work shows for the first time that with increasing severity of OA, the proportion of cells positive for the progenitor/stem cell marker CD166 (Lee et al. 2009, Pretzel et al. 2011) also increases. With progressive OA, the chondrocytes appear to assume a more immature phenotype. We therefore decided to study the reverse process and determine how the TLR phenotype of the progenitor cells changes during chondrogenesis. The TLR profile was dependent on the developmental stage of the differentiating cells, with TLRs being lower in the differentiated cells than in the day-14 intermediate and day-7 early progenitors. Thus, inflammatory chondrocytes in severe OA show a more embryonic, progenitor TLR phenotype than chondrocytes in mild OA (Lee et al. 2009). This is in accordance with reports describing chondrocyte progenitors in OA (Alsalameh et al. 2004, Grogan et al. 2009, Koelling et al. 2009, Pretzel et al. 2011), bioinformatics analysis of OA (Pitsillides and Beier 2011), and the present observations on TLRs.

We found that TLR1 and TLR2 are expressed during chondrogenesis, in mature primary chondrocytes, and in degenerated chondrocytes in OA. Therefore, if cartilage degeneration in OA leads to a release of matrix-derived danger signals, they might be recognized by the TLRs of the close-by chondrocytes. The expression of TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 increased with the severity of the disease until grade 3–4, suggesting that danger signals and inflammatory cytokines may regulate chondrocyte TLRs in OA. This work suggests that OA might act as an autoinflammatory disease and links the old mechanical wear-and-tear concept with a modern paradigm of OA as a biochemically-mediated autoinflammatory condition.

In this work, we studied only the effect of TNF-α on chondrocytes. Although it seemed to regulate TLR2 mRNA expression and (somewhat less) TLR1 mRNA expression, TLR4 and TLR9 mRNA expression levels were not affected. This suggests that in the upregulation of TLR4 and TLR9, other inflammatory cytokines and danger signals probably have more important roles. Indeed, TLR4 expression has been shown to be upregulated by IL-1β (Campo et al. 2012), by alarmins such as S100A8 and S100A9 (Schelbergen et al. 2012), and by low-molecular-weight hyaluronan (Campo et al. 2010). On the other hand, stimulation with TLR4 ligands has been shown to increase IL-1β expression in chondrocytes (Bobacz et al. 2007). It may therefore be that different cytokines play different roles in upregulation of various TLRs and their positive feedback loops. Thus, further studies are necessary to determine the exact roles of different cytokines and danger signals in modulating the expression levels of individual TLRs during the pathogenesis of OA.

Acknowledgments

TS, GB, PC, YK, and DN participated in the conception and design of the study. AS, MK, MH, and PY participated in the acquisition of patient samples. All authors participated in the acquisition of data. TS, GB, RG, YK, and DN analyzed and interpreted the data. All the authors participated in drafting and revising the article, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

The work was supported by Finska Läkaresällskapet, the National Graduate School of Musculoskeletal Diseases and Biomaterials, Orion-Farmos Research Foundation, evo grants, ORTON Orthopaedic Hospital of the Invalid Foundation, the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, the Danish Council for Strategic Research, and the European Science Foundation “Regenerative Medicine” RNP.

Supplementary material

Supplementary figure and methods are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 6158.

References

- Alsalameh S, Amin R, Gemba T, Lotz M. Identification of mesenchymal progenitor cells in normal and osteoarthritic human articular cartilage . Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1522–32. doi: 10.1002/art.20269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M E. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger . J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(1):1–5. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobacz K, Sunk I G, Hofstaetter J G, Amoyo L, Toma C D, Akira S, et al. Toll-like receptors and chondrocytes: the lipopolysaccharide-induced decrease in cartilage matrix synthesis is dependent on the presence of toll-like receptor 4 and antagonized by bone morphogenetic protein 7 . Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(6):1880–93. doi: 10.1002/art.22637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Ohlsson C, Isaksson O, Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation . N Engl J Med. 1994;331(14):889–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittberg M, Tallheden T, Sjögren-Jansson B, Lindahl A, Peterson L. Autologous chondrocytes used for articular cartilage repair: an update . Clin Orthop (Suppl) 2001;391:S337–48. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200110001-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo G M, Avenoso A, Campo S, D’Ascola A, Nastasi G, Calatroni A. Small hyaluronan oligosaccharides induce inflammation by engaging both toll-like-4 and CD44 receptors in human chondrocytes . Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80(4):480–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo G M, Avenoso A, D’Ascola A, Scuruchi M, Prestipino V, Nastasi G, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor activation and hyaluronan fragment inhibition reduce inflammation in mouse articular chondrocytes stimulated with interleukin-1β . FEBS J. 2012;279(12):2120–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z L. Important aspects of Toll-like receptors, ligands and their signaling pathways . Inflamm Res. 2010;59(10):791–808. doi: 10.1007/s00011-010-0208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erridge C. Endogenous ligands of TLR2 and TLR4: agonists or assistants? . J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87(6):989–99. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1209775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrafa E, Imberti L, Tiberio G, Prandini A, Giulini S M, Caimi L. Heterogeneous expression of toll-like receptors in lymphatic endothelial cells derived from different tissues . Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89(3):475–81. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan S P, Miyaki S, Asahara H, D’Lima D D, Lotz M K. Mesenchymal progenitor cell markers in human articular cartilage: normal distribution and changes in osteoarthritis . Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(3):R85. doi: 10.1186/ar2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinegård D, Saxne T. The role of the cartilage matrix in osteoarthritis . Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(1):50–6. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson C P, Ye S. Toll-like receptors, their ligands, and atherosclerosis . Sci World J. 2011;11:437–53. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H A, Cho M L, Choi H Y, Yoon C S, Jhun J Y, Oh H J, Kim H Y. The catabolic pathway mediated by Toll-like receptors in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes . Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(7):2152–63. doi: 10.1002/art.21951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelling S, Kruegel J, Irmer M, Path J R, Sadowski B, Miro X, Miosge N. Migratory chondrogenic progenitor cells from repair tissue during the later stages of human osteoarthritis . Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(4):324–35. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konttinen Y T, Sillat T, Barreto G, Ainola M, Nordström D C. Osteoarthritis as an autoinflammatory disease caused by chondrocyte-mediated inflammatory responses . Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):613–6. doi: 10.1002/art.33451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C C, Avalos A M, Ploegh H L. Accessory molecules for Toll-like receptors and their function . Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(3):168–79. doi: 10.1038/nri3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H J, Choi B H, Min B H, Park S R. Changes in surface markers of human mesenchymal stem cells during the chondrogenic differentiation and dedifferentiation processes in vitro . Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(8):2325–32. doi: 10.1002/art.24786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu-Bryan R, Pritzker K, Firestein G S, Terkeltaub R. TLR2 signaling in chondrocytes drives calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate and monosodium urate crystal-induced nitric oxide generation . J Immunol. 2005;174(8):5016–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu-Bryan R, Terkeltaub R. Chondrocyte innate immune myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent signaling drives procatabolic effects of the endogenous Toll-like receptor 2/Toll-like receptor 4 ligands low molecular weight hyaluronan and high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in mice . Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(7):2004–12. doi: 10.1002/art.27475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozinsky A, Underhill D M, Fontenot J D, Hajjar A M, Smith K D, Wilson C B, et al. The repertoire for pattern recognition of pathogens by the innate immune system is defined by cooperation between toll-like receptors . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(25):13766–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250476497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitsillides A A, Beier F. Cartilage biology in osteoarthritis—lessons from developmental biology . Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(11):654–63. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretzel D, Linss S, Rochler S, et al. Relative percentage and zonal distribution of mesenchymal progenitor cells in human osteoarthritic and normal cartilage . Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(2):R64. doi: 10.1186/ar3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritzker K P, Gay S, Jimenez SA, Ostergaard K, Pelletier J P, Revell P A, Salter D, van den Berg W B. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage . 2006;14(1):13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raicevic G, Najar M, Stamatopoulos B, De Bruyn C, Meuleman N, Bron D, et al. The source of human mesenchymal stromal cells influences their TLR profile as well as their functional properties . Cell Cell Immunol. 2011;270(2):207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu-Mourez R, Franã§ois M, Boivin M N, Bouchentouf M, Spaner D E, Galipeau J. Cytokine modulation of TLR expression and activation in mesenchymal stromal cells leads to a proinflammatory phenotype . J Immunol. 2009;182(12):7963–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanzello C R, Plaas A, Crow M K. Innate immune system activation in osteoarthritis: is osteoarthritis a chronic wound? . Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20(5):565–72. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32830aba34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelbergen R F, Blom A B, van den Bosch M H, Slöetjes A, Abdollahi-Roodsaz S, Schreurs B W, et al. Alarmins S100A8 and S100A9 elicit a catabolic effect in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes that is dependent on Toll-like receptor 4 . Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(5):1477–87. doi: 10.1002/art.33495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillat T, Pöllänen R, Lopes J R, Porola P, Ma G, Korhonen M, et al. Intracrine androgenic apparatus in human bone marrow stromal cells . J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(9B):3296–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00729.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires G R, Okouneff S, Ionescu M, Poole A R. The pathobiology of focal lesion development in aging human articular cartilage and molecular matrix changes characteristic of osteoarthritis . Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(5):1261–70. doi: 10.1002/art.10976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S L, Tsai C D, Lee C H, Salter D M, Lee H S. Expression and regulation of Toll-like receptor 2 by IL-1β and fibronectin fragments in human articular chondrocytes . Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(10):879–86. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K. Evolution and integration of innate immune recognition systems: the Toll-like receptors . J Endotoxin Res. 2005;11(1):51–5. doi: 10.1179/096805105225006687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Osch G J, Brittberg M, Dennis J E, et al. Cartilage repair: past and future—lessons for regenerative medicine . J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(5):792–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.