Abstract

Damage of oligodendrocytes after ischemia has negative impact on white matter integrity and neuronal function. In this work, we explore whether Netrin-1 (NT-1) overexpression facilitates white matter repairing and remodeling. Adult CD-1 mice received stereotactic injection of adeno-associated virus carrying NT-1 gene (AAV-NT-1). One week after gene transfer, mice underwent 60 minutes of middle cerebral artery occlusion. The effect of NT-1 on neural function was evaluated by neurobehavioral tests. Proliferated oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), newly matured oligodendrocytes, and remyelination were semi-quantified by immunohistochemistry. The role of NT-1 in oligodendrogenesis was further explored by examining specific NT-1 receptors and their function. Netrin-1 overexpression was detected in neurons and astrocytes 2 weeks after AAV-NT-1 gene transfer and significantly improved the neurobehavioral outcomes compared with the control (P<0.05). In comparison with the control, proliferated OPCs, newly matured oligodendrocytes, and remyelination were greatly increased in the ipsilateral hemisphere of AAV-NT-1-transduced mice. Furthermore, both NT-1 receptors deleted in colorectal carcinoma and UNC5H2 were expressed on OPCs whereas only UNC5H2 was expressed in myelinated axons. Our study indicated that NT-1 promoted OPC proliferation, differentiation, and increased remyelination, suggesting that NT-1 is a promising factor for white matter repairing and remodeling after ischemia.

Keywords: ischemia, netrin-1, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, remyelination, white matter

Introduction

Oligodendrocytes produce the main components of myelin in the brain, mainly derived from the maturation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) during development or after brain injury in adulthood.1 Myelins are essential for axon integrity and functional electrical impulse transmission. Damage to oligodendrocyte leads to disruption of myelin structure and function, exacerbating motor function and other neurobehavioral performances.2 For example, neurobehavioral outcomes are greatly destroyed when myelins are damaged in multiple sclerosis.3 Cerebral ischemia not only damages gray matter neurons but also white matter glial cells including oligodendrocytes and myelin. Because of relatively low blood supply during ischemia, oligodendrocytes are particularly susceptible to ischemic damage due to excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and other cellular mechanisms.4

In the past decade, neuroprotective drugs were proved effective in experimental stroke but failed in human clinical trials. One reason may lie in that these drugs are targeted at gray matter. However, human brain consists of two major components with almost the same volume.5 Protection and remodeling on white matter are often neglected, especially in the postischemic recovery period. Therefore, additional attention should be paid to white matter protection in acute ischemic stroke and repairing during recovery phase. White matter repairing refers to increasing endogenous OPCs, which occupy 5% to 8% glial cells in the brain. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells can differentiate into mature oligodendrocytes and participate in remyelination during central nervous system injuries including cerebral ischemia.

During the spontaneous recovery period after ischemic stroke, angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and oligodendrogenesis occur to promote tissue repairing and remodeling.6 However, the endogenous recovery process is usually insufficient. New approaches should be considered to promote more aspects of recovery progress after ischemic brain injury.

Netrin-1 (NT-1), a lamina-related protein, has a pivotal role in axon guidance. During central nervous system development, NT-1 either attracts or repels axon outgrowth depending on its binding receptors.7 Netrin-1 also influences small blood vessel development and tissue morphogenesis.8, 9 Another important function of NT-1 in development is to affect white matter development by influencing OPC proliferation, differentiation, and migration.10, 11 Under pathologic conditions, NT-1 has many roles in various systems. It inhibits inflammation and apoptosis and promotes repairing after ischemic stroke by increasing angiogenesis.12, 13, 14, 15 However, the effect of NT-1 on white matter repairing after ischemic brain injury has not been explored yet. In the present study, we aim to investigate whether NT-1 overexpression could improve white matter repairing and remodeling after ischemic stroke, and if so, the possible role of NT-1 will be further studied.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental Design

This study was carried out in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. Animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China. Mice were housed under standard laboratory conditions. Adult male CD-1 mice(n=81) aged 6 to 8 weeks, weighing 25 to 30 g were divided into three groups: (1) adeno-associated virus carrying NT-1 gene (AAV-NT-1) group, 27 mice underwent AAV-NT-1 gene transfer; (2) adeno-associated virus carrying green fluorescent protein (AAV-GFP) group, 27 mice underwent AAV-GFP gene transfer as a viral vector control, and (3) Phosphate buffer solution (PBS) group, 27 mice underwent PBS injection as a non-viral control. Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) was performed after 1 week of AAV-NT-1, AAV-GFP, or PBS injection. Neurobehavioral tests were examined at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after tMCAO. Netrin-1 expression and its function were further determined by immunohistochemistry and western blot analysis.

Adeno-Associated Virus-Netrin-1 Virus Production

Adeno-associated virus was packaged and titered as described previously.16 Briefly, pAAV-NT-1, pHelper, and pAAV-RC plasmid were co-transfected into AAV-293 cells. Six hours after transfection, cells were switched to Dulbecco's modified eagle medium plus 2% fetal bovine serum. The supernatant was collected 48 hours after transfection and purified with chloroform.17 After purification, the viral titer was determined by real-time PCR.18 Adeno-associated virus-green fluorescent protein was prepared using the same protocol.

Adeno-Associated Virus-Netrin-1 Gene Transfer into Mouse Brain

Adult CD-1 mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100 mg/10 mg per kg, Sigma, San Louis, MO, USA) intraperitoneally. The mice were fixed on a stereotaxic plate (RWD, Shenzhen, China). A 0.5 mm bone hole was drilled by a hand drill (Fine Science Tool, foster City, CA, USA). Five microliters of AAV-NT-1 (containing 1 × 1011 particles) was slowly injected into the left striatum AP=−0.02 mm, ML=−2.5 mm, DV=3 mm relative to the bregma using a mini pump (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA). The needle was kept in the brain for additional 5 minutes and after injection, the needle was withdrawn. The bone hole was sealed, the wound was sutured, and animals were returned to their cages after awake.19

Transient Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion in Mice

After 1 week of AAV-NT-1 transduction, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine. Body temperature was maintained at 37±0.5°C using a heating pad (RWD). Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion was performed as previously described.15 Briefly, a 6-0 silicone-coated suture (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) was inserted from the left external carotid artery into the internal carotid artery to occlude the origin of the middle cerebral artery. Successful occlusion was demonstrated by the decrease of surface cerebral blood flow to 10% of baseline cerebral blood flow using a Laser Doppler flowmetry (Moor LAB, Devon, UK). Reperfusion was performed by withdrawing the suture 60 minutes after MCAO.

Immunofluorescent Staining

After sacrificing animals, the brains were removed and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde fixation solution at 4°C overnight. After fixation, brains were dehydrated in 30% sucrose solution and sectioned in 30-μm thickness. For myelin basic protein (MBP) staining, sections were rinsed by PBS 5 minutes for three times, blocked by 5% normal donkey serum for 60 minutes at room temperature, incubated with MBP antibody (1:500 dilution, Abcam, Beverly, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight. After rinsing, sections were incubated with conjugated secondary immunoglobulin G for 60 minutes at room temperature. The intensity of fluorescence was determined by ImagePro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). The ratio of mean intensity between the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres was calculated. Double-staining procedure was as follows: brain sections were incubated with NT-1 (1:200 dilution, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and NeuN (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz Technology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); NT-1 and GFAP (1:300 dilution, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA); and NT-1 and Glut-1 (1:200 dilution, Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). For NT-1 receptor detection, the brain sections were incubated with deleted in colorectal carcinoma (DCC) (1:300 dilution, Santa Cruz) and CD140α (1:100 dilution, Millipore), MBP (1:500 dilution, Abcam) separately; UNC5H2 (1:300 dilution, R&D systems) was incubated with CD140α (1:100 dilution, Millipore), MBP (1:500 dilution, Abcam) separately at 4°C overnight, then sections were washed by PBS, and proper secondary antibodies were incubated individually at room temperature. After rinsing with PBS, sections were mounted and examined under a confocal microscope (Leica, Solms, Germany). Photomicrographs were taken for further data analysis.

BrdU Staining and Cell Counting

BrdU powder (Sigma) was dissolved in normal saline in a concentration of 65 mmol/L. BrdU solution was injected intraperitoneally at 50 mg/kg twice a day for two time phases for 3 consecutive days: 4 to 6 days after MCAO surgery and 3 days before killing animals. For BrdU double staining, sections were first treated with 2 mol/L HCl for 30 minutes at room temperature and then with sodium borate twice each for 10 minutes. Sections were then treated with 0.3% Triton–PBS for 30 minutes, blocked by 5% normal donkey serum, incubated with anti- BrdU (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz), CD140α (1:100 dilution, Millipore), oligodendrocyte-specific protein (OSP, 1:200 dilution, Abcam) at 4°C overnight. The sections were incubated with secondary antibodies for 60 minutes at room temperature. After rinsing with PBS, sections were mounted. Photomicrographs were taken with a confocal microscope. BrdU/CD140α or BrdU/OSP-positive cells were counted by investigators who are masked to the treatment. Double-positive cells were counted from a single optical fraction in six sections for a mouse (360 μm between bregma −1.54 mm and bregma 0.62 mm).

Western Blot Analysis

Protein used in western blot experiments was isolated from the striatum. Mice were anesthetized by ketamine/xylazine intraperitoneally. After anesthesia, brains were quickly removed to a cooled brain mold, and then cut into four sections by five blades that are 2 mm apart; the second rostral section including ischemic core was collected. The section was divided into contralateral cortex, striatum and ipsilateral cortex, striatum using micro forceps under microscope. The protein extracted from the ipsilateral striatum was used for further western blot analysis. For protein extraction, tissues were first homogenized by ultrasonic on ice and then centrifuged. Equal amount of total protein (40 μg) was loaded on 10% (W/V) SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 60 minutes at room temperature and subsequently with anti-chicken NT-1 antibody (1:1000 dilution, Abcam) and anti-β-actin antibody (1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz) at 4°C overnight. The membrane was washed in Tris-buffered saline tween-20 and incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-goat immunoglobulin G for 120 minutes at room temperature, and then reacted with an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The result of chemiluminescence was recorded and semi-quantified by Quantity One imaging software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Neurobehavioral Tests

Mice were trained for 3 consecutive days before tMCAO surgery. Neurobehavioral tests were performed before MCAO and at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after tMCAO by an investigator who was masked to the experimental groups.20

Rotarod Test

An accelerating rotarod (Zhenghua, Anhui, China) provides an index of motor coordination and balance with its velocity slowly increasing from 5 to 40 r.p.m. The duration that mice maintained on the accelerating rotarod was measured. Each animal was given three trials and the longest time animals spent on the rod was recorded.

Beam Walk

For beam walk test, mice were trained to traverse a horizontally elevated square beam with 7 mm side length to reach an escape platform placed 1 m away. Mice were placed on one end of the beam and the latency to traverse 80% of the beam towards the escape platform was recorded. Data from motor tests were analyzed as mean latency to cross the beam from three trials.

Neurologic Score

Modified neurologic severity scores of the animals were graded on a scale of 0 to 14, which is a composite of motor, reflex, and balance tests.21

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean±s.d. Bonferroni post hoc comparison was used to analyze the difference between groups at each time point. Other data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey post hoc comparisons using GraphPad Instat version 3.05 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). P value<0.05 was considered as statistical significance.

Results

Netrin-1 Overexpression in the Mouse Brain

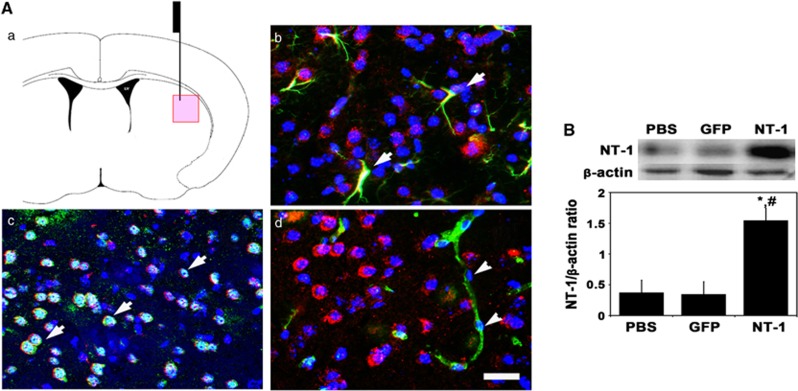

Netrin-1 expression was examined 2 weeks after AAV-NT-1 injection. We found that chicken NT-1 was highly expressed in the AAV-NT-1-injected hemisphere after 2 weeks of gene transfer. Netrin-1 mainly expressed in neurons and astrocytes, but not in endothelial cells (Figure 1A). Western blot further showed that chicken NT-1 was significantly increased in AAV-NT-1-transduced mice compared with AAV-GFP-transduced and PBS-treated mice (Figures 1B, P<0.01).

Figure 1.

Netrin-1 (NT-1) overexpression in the mouse brain after adeno-associated virus (AAV)-NT-1 injection. (A) Photomicrographs showed the AAV-NT-1 injection region (a) and arrowheads indicated NT-1 (red) merged with glial fibrillary acidic protein positive (astrocytes, b), NeuN positive (neurons, c), but not in Glut-1-positive cells (endothelial cell marker, d). Scale bar, 30 μm. (B) Western blot showed NT-1 expression in AAV-NT-1-injected hemisphere of mouse brain after 2-week gene transfection. Bar graph represented NT-1 expression in AAV-NT-1, AAV-GFP, and phosphate buffer solution (PBS)-treated mice. P<0.01, NT-1 versus green fluorescent protein (GFP) (*) and (#) PBS group, n=3 per group.

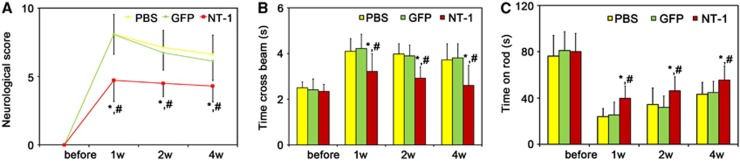

Netrin-1 Overexpression Improved Neurobehavioral Outcomes

As indexes of motor function, the beam walk test, and rotarod test in AAV-NT-1-transduced mice were greatly improved compared with AAV-GFP-transduced or PBS-treated mice at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after tMCAO (Figures 2B and 2C, P<0.05). To examine whether NT-1 influenced other aspects of neurobehavioral outcomes, we examined modified neurologic severity scores in these animals. The modified neurologic severity score was lower in AAV-NT-1-transduced mice than in AAV-GFP-transduced and PBS-treated mice (Figure 2A, P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Netrin-1 (NT-1) overexpression improved the behavioral outcomes. The neurologic score (A), beam walk test (B), and rotarod test (C) were performed separately to observe the behavior outcomes 1, 2, and 4 weeks after middle cerebral artery occlusion surgery. Data were presented as mean±s.d., n=8 in each group. phosphate buffer solution (PBS), PBS-treated mice; green fluorescent protein (GFP), adeno-associated virus (AAV)-GFP-treated mice; NT-1, AAV-NT-1-treated mice. P<0.05, AAV-NT-1 versus AAV-GFP (*) and (#) PBS group.

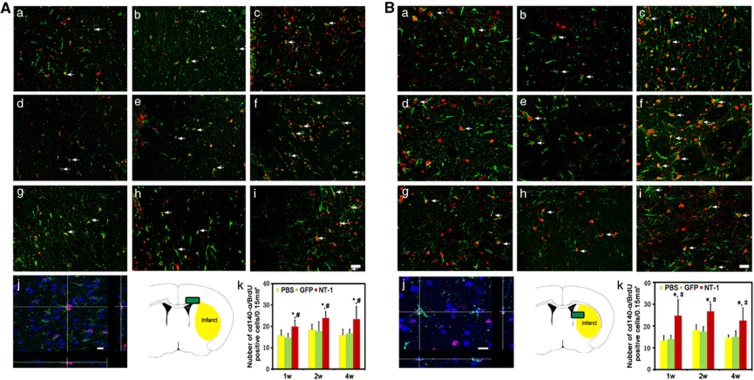

Netrin-1 Overexpression Improved Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cell Proliferation and Maturation

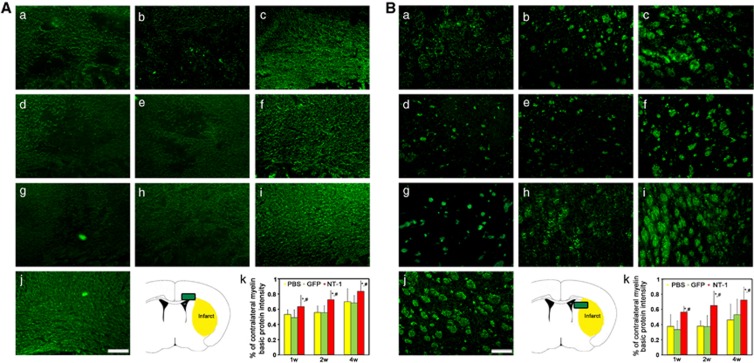

Brain sections were double labeled with CD140α and BrdU for evaluation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cell proliferation. Compared with the control, the number of CD140α and BrdU-positive OPCs were significantly increased in AAV-NT-1-transduced mice after tMCAO (Figures 3A and 3B, P<0.01), suggesting that NT-1 facilitates OPC proliferation. Oligodendrocyte-specific protein and BruU labeling were used to detect newly matured oligodendrocytes in the striatum and corpus callosum. In comparison with the control, the number of BrdU-positive oligodendrocytes were significantly increased 1 week after tMCAO and sustained for at least 4 weeks in AAV-NT-1-transduced mice (Figures 4A and 4B, P<0.01). This result suggested that NT-1 could promote OPC proliferation and the OPCs could further differentiate into newly matured oligodendrocytes.

Figure 3.

Proliferated oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) in corpus callosum and striatum. Double-labeled BrdU and CD140α immunostaining was performed to demonstrate proliferation of OPCs. Photomicrographs showed BrdU (red)- and CD140α (green)-positive staining in the corpus callosum (A) and striatum (B). Proliferating OPCs (BrdU/CD140α-positive cells) were detected in phosphate buffer solution (PBS)-treated (a, d, g), adeno-associated virus (AAV)- green fluorescent protein (GFP)-treated (b, e, h), and AAV- Netrin-1 (NT-1)-treated (c, f, i) mice at 1 (a, b, c), 2 (d, e, f), and 4 weeks (g, h, i) after gene transfer. Three-dimensional photomicrograph of BrdU/CD140α staining showed real merged cell (j), Scale bar, 30 μm (i) and 10 μm (j). Photos were taken from corpus callosum and striatum, respectively (Ak, Bk). Bar graph showed the number of BrdU/CD140α double-positive staining in corpus callosum and striatum. P<0.01, AAV-NT-1 versus PBS (*) and AAV-NT-1 versus AAV-GFP (#) group, n=8 per group at each time point.

Figure 4.

New matured oligodendrocytes in corpus callosum and striatum. Double-labeled BrdU and oligodendrocyte-specific protein (OSP) immunostaining was performed to demonstrate the newly matured oligodendrocyte. Photomicrographs showed BrdU (red)- and OSP (green)-positive staining in the corpus callosum (A) and striatum (B). Newly matured oligodendrocytes (BrdU/OSP-positive cells) were detected in phosphate buffer solution (PBS)-treated (a, d, g), adeno-associated virus (AAV)- green fluorescent protein (GFP)-treated (b, e, h), and AAV- Netrin-1 (NT-1)-treated (c, f, i) mice at 1 (a, b, c), 2 (d, e, f), and 4 weeks (g, h, i) after gene transfection. Three-dimensional photomicrograph of BrdU/OSP staining showed real merged cell (j), scale bar, 30 μm (i), and 10 μm (j). Photos were taken from corpus callosum and striatum, respectively (Ak, Bk). Bar graph showed the number of BrdU/OSP double-positive staining in corpus callosum and striatum. P<0.01, AAV-NT-1 versus PBS (*), and AAV-NT-1 versus AAV-GFP (#) group, n=8 per group at each time point.

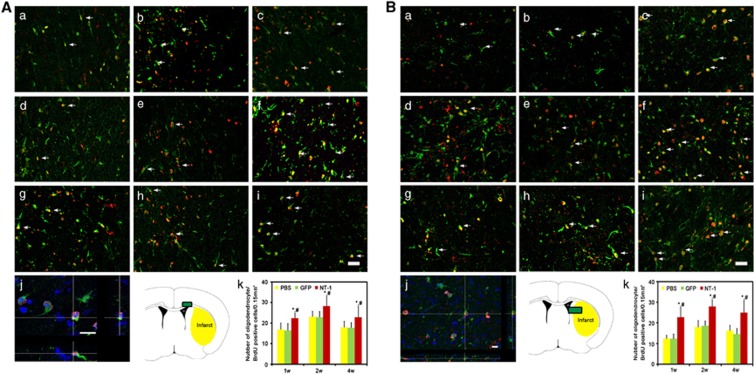

Netrin-1 Overexpression Promoted White Matter Integrity

Myelin basic protein immunostaining was used to detect the white matter morphologic changes. After tMCAO, many small cavities in the ipsilateral corpus callosum were detected, whereas white matter maintained intact morphology in the contralateral hemisphere (Figure 5Aj). In the striatum, the injured axons collapsed and neurofilaments broke down in the ipsilateral hemisphere, whereas axons and fibers presented integrity structure in contralateral hemisphere (Figure 5Bj). As an indicator of white matter integrity, the ratio of MBP intensity of the ipsilateral over the contralateral hemispheres in AAV-NT-1-transduced mice was much higher than that of AAV-GFP-transduced and PBS-treated mice (P<0.05), both in the corpus callosum and striatum (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The morphology of myelined fibers in corpus callosum and striatum. The myelin basic protein (MBP) was stained in corpus callosum and striatum to detect the white matter injuries. Photomicrographs showed MBP-positive fibers in the corpus callosum (A) and striatum (B). MBP-positive fibers were examined in phosphate buffer solution (PBS)-treated (a, d, g), adeno-associated virus (AAV)- green fluorescent protein (GFP)-treated (b, e, h), and AAV-NT-1-treated (c, f, i) mice at 1 (a, b, c), 2 (d, e, f), and 4 weeks (g, h, i) after gene transfer. Myelin basic protein-positive fibers were clearly presented in contralateral corpus callosum (A, j) and striatum (B, j). Scale bar, 30 μm. Photos were taken from the corpus callosum and striatum, respectively (A, k and B k). Bar graph showed MBP intensity between ipsilateral and contralateral in the corpus callosum and striatum. P<0.05, AAV- Netrin-1 (NT-1) versus PBS (*) and AAV-NT-1 versus AAV-GFP (#) group, n=8 per group at each time point.

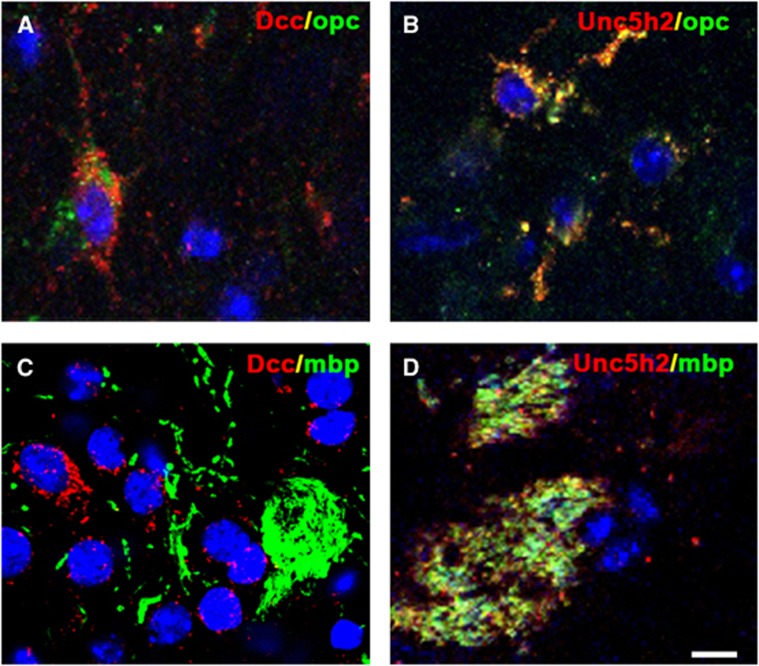

Effects of Netrin-1 on White Matter were Dependent on DCC and UNC5H2

The effects of NT-1 on white matter were dependent on its binding receptors. Immunostaining results revealed that both DCC and UNC5H2 were expressed in the cytoplasm of OPCs (Figures 6A and 6B). In contrast, UNC5H2 was expressed on the MBP-positive fibers, whereas DCC receptor was absent (Figures 6C and 6D). These results implied that NT-1 had different roles in oligodendrogenesis.

Figure 6.

Expression of Netrin-1 (NT-1) receptors in white matter. Two receptors of NT-1 were detected by immunohistochemistry, both of deleted in colorectal carcinoma (DCC) (A) and UNC5H2 (B) expressed in the oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. However, only UNC5H2 (D) expressed in myelin basic protein-positive fibers, no DCC was detected (C). Scale bar, 5 μm.

Discussion

Oligodendrogenesis is involved in brain tissue repairing and remodeling after ischemic brain injury.22, 23 Promoting white matter remodeling via pharmacological intervention or cell-based therapy improved motor function recovery.24, 25 In the present work, we studied the effect of NT-1 on white matter remodeling in tMCAO mice. We found that ischemia-induced motor function damage was greatly attenuated in AAV-NT-1-transduced mice in contrast with the Control. Increased NT-1 expression promoted OPC proliferation and maturation, subsequently enhancing focal remyelination. The spontaneous recovery after ischemic injuries involves not only angiogenesis and neurogenesis but also oligodendrogenesis.26 These remodeling progresses contribute to the recovery of motor function after ischemic injury. Our previous study demonstrated that NT-1 overexpression promotes angiogenesis. In this study, we further demonstrated that NT-1 overexpression promoted oligodendrogenesis. Therefore, angiogenesis and oligogenesis appear both contributing to the functional recovery.

The effects of NT-1 on white matter development have been widely investigated. Netrin-1 is secreted by neurons and oligodendrocytes in the central canal, which conduces to generating an appropriate amount of oligodendrocytes by promoting OPC proliferation.10 Netrin-1 also supports oligodendrocytes development by promoting OPC migration.11 On the axon myelination process, NT-1 increases the branching of oligodendrocyte process.27 In the peripheral nervous system, NT-1 promotes proliferation of Schwann cells, which possess the same function as oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system. Under ischemic conditions, NT-1 could be re-activated, suggesting that it may be a target for ischemic stroke treatment.28 In the acute phase of ischemia, NT-1 reduces the infarct volume by inhibiting apoptosis, and improves synapse plasticity by changing the long-term potential.29, 30 Our previous study showed that NT-1 overexpression improved neurobehavioral performance by promoting focal angiogenesis and reduced infarct volume in a long-term study. Our current data suggest that NT-1 overexpression also restores myelination by increasing the number of proliferated OPCs in both the corpus callosum and striatum. This effect is consistent with the role of NT-1 in the developmental progress. Although NT-1 mainly acts as a guidance factor during both development and adulthood, it also increases the proliferation of renal proximal tubular epithelial cells as well as endothelial cells.31, 32 Consistent with NT-1 on white matter development, we demonstrated that NT-1 also preserves the similar function during ischemia by enhancing OPC proliferation and participating in white matter repairing and remodeling, which may contribute to improvement in neurobehavioral outcomes after ischemic brain injury.

Function of NT-1 relies on the combined receptors in various systems. Most broadly studied receptors of NT-1 are DCC and UNC5H2, but their functions in brain injury are still unknown, especially in the white matter system.7 Both DCC and UNC5H2 are involved in the development of oligodendrocyte.33 Netrin-1 binding with DCC displays both attraction and repelling effect whereas NT-1 binding with UNC5H2 mainly showed repelling role.34 The proliferation of Schwann cells also requires UNC5H2 participation.35 We found that both DCC and UNC5H2 were expressed on the cytoplasm of OPCs, implying that these two receptors were probably associated with the proliferative effects of NT-1 on OPCs after ischemic stroke. In contrast, immunohistochemistry showed that only UNC5H2 was detected on the MBP-positive fibers, indicating that UNC5H2 may be relevant with forming the sheath of axons and maintaining white matter integrity. Currently, DCC or UNC5H2 antagonists are commercially unavailable. Antibodies can be used to block DCC or UNC5H2;36, 12 however, the BBB limits accessibility of antibody into the brain. Although we demonstrated the neurobehavioral outcome improved and oligodendrocytes were increased in AAV-NT-1 transduced mice; future study is needed when proper blockers are developed for these receptors.

Our results demonstrated that NT-1 overexpression also promoted long-time recovery after ischemic stroke by improving oligodendrogenesis and white matter repairing. As NT-1 gene transfer and overexpression of NT-1 were achieved before MCAO, the protective effect of NT-1 such as anti-apoptosis or anti-inflammation,37, 38 which have been presented in other systems such as kidney, could not be excluded. Hence, further study is needed to understand the protective effects of NT-1 on early pathologic mechanism in the acute phase of stroke.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This study is supported by China 973 Program #2011CB504405 (GYY, YW) and the NSFC Projects #81070939 (GYY) and #81100868 (YW). The authors thank M Xiaoyan Chen for her editorial assistance and the staffs of the Neuroscience and Neuroengineering Center for their collaborative support.

References

- Emery B. Regulation of oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Science. 2010;330:779–782. doi: 10.1126/science.1190927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoni L, Garcia JH, Gutierrez JA. Cerebral white matter is highly vulnerable to ischemia. Stroke. 1996;27:1641–1647. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, Rudick R, Mörk S, Bö L. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:278–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai K, Lo EH. Oligovascular signaling in white matter stroke. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:1639–1644. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MP, Ransom BR. New light on white matter. Stroke. 2003;34:330–332. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000054048.22626.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Shen F, Degos V, Schonemann M, Pleasure SJ, Mellon SH, et al. Oligogenesis and oligodendrocyte progenitor maturation vary in different brain regions and partially correlate with local angiogenesis after ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2:366–375. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford DK, Cole SJ, Cooper HM. Netrin-1: diversity in development. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Le Noble F, Yuan L, Jiang Q, De Lafarge B, Sugiyama D, et al. The netrin receptor unc5b mediates guidance events controlling morphogenesis of the vascular system. Nature. 2004;432:179–186. doi: 10.1038/nature03080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan K, Strickland P, Valdes A, Shin GC, Hinck L. Netrin-1/neogenin interaction stabilizes multipotent progenitor cap cells during mammary gland morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2003;4:371–382. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HH, Macklin WB, Miller RH. Netrin-1 is required for the normal development of spinal cord oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1913–1922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3571-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassky N, de Castro F, Le Bras B, Heydon K, Quéraud-LeSaux F, Bloch-Gallego E, et al. Directional guidance of oligodendroglial migration by class 3 semaphorins and netrin-1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5992–6004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05992.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger P, Schwab JM, Mirakaj V, Masekowsky E, Mager A, Morote-Garcia JC, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent induction of netrin-1 dampens inflammation caused by hypoxia. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:195–202. doi: 10.1038/ni.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Reeves WB, Ramesh G. Netrin-1 and kidney injury. I. Netrin-1 protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury of the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F739–F747. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00508.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Le T, Chang TTJ, Habib A, Wu S, Shen F, et al. AAV-mediated netrin-1 overexpression increases peri-infarct blood vessel density and improves motor function recovery after experimental stroke. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;44:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Wang Y, He X, Yuan F, Lin X, Xie B, et al. Netrin-1 hyperexpression in mouse brain promotes angiogenesis and long-term neurological recovery after transient focal ischemia. Stroke. 2012;43:838–843. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.635235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Shen F, Chen Y, Hao Q, Liu W, Su H, et al. Overexpression of netrin-1 induces neovascularization in the adult mouse brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1543–1551. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Dong X, Wu Z, Cao H, Niu D, Qu J, et al. A novel method for purification of recombinant adenoassociated virus vectors on a large scale. Chin Sci Bull. 2001;46:485–488. [Google Scholar]

- Rohr UP, Heyd F, Neukirchen J, Wulf MA, Queitsch I, Kroener-Lux G, et al. Quantitative real-time PCR for titration of infectious recombinant aav-2 particles. J Virol Methods. 2005;127:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen F, Fan Y, Su H, Zhu Y, Chen Y, Liu W, et al. Adeno-associated viral vector-mediated hypoxia-regulated vegf gene transfer promotes angiogenesis following focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Gene ther. 2007;15:30–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Shen F, Frenzel T, Zhu W, Ye J, Liu J, et al. Endothelial progenitor cell transplantation improves long term stroke outcome in mice. Ann Neurol. 2009;67:488–497. doi: 10.1002/ana.21919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Chen J, Chen X, Wang L, Gautam S, Xu Y, et al. Human marrow stromal cell therapy for stroke in rat neurotrophins and functional recovery. Neurology. 2002;59:514–523. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Nogawa S, Suzuki S, Dembo T, Kosakai A. Upregulation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells associated with restoration of mature oligodendrocytes and myelination in peri-infarct area in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2003;989:172–179. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar D, Underhill SM, Goldberg MP. Oligodendrocytes and ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:263–274. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000053472.41007.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai M, Stetler RA, Xing J, Hu X, Gao Y, Zhang W, et al. Enhanced oligodendrogenesis and recovery of neurological function by erythropoietin after neonatal hypoxic/ischemic brain injury. Stroke. 2010;41:1032–1037. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen LH, Li Y, Chen J, Zhang J, Vanguri P, Borneman J, et al. Intracarotid transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells increases axon-myelin remodeling after stroke. Neuroscience. 2006;137:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC. Repairing the human brain after stroke: I. Mechanisms of spontaneous recovery. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:272–287. doi: 10.1002/ana.21393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekharan S, Baker KA, Horn KE, Jarjour AA, Antel JP, Kennedy TE. Netrin 1 and dcc regulate oligodendrocyte process branching and membrane extension via fyn and rhoa. Development. 2009;136:415–426. doi: 10.1242/dev.018234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya A, Hayashi T, Deguchi K, Sehara Y, Yamashita T, Zhang H, et al. Expression of netrin-1 and its receptors dcc and neogenin in rat brain after ischemia. Brain Res. 2007;1159:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TW, Li WW, Li H. Netrin-1 attenuates ischemic stroke-induced apoptosis. Neuroscience. 2008;156:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat M, Baluchnejadmojarad T, Roghani M, Goshadrou F, Ronaghi A, Mehdizadeh M. Netrin-1 improves spatial memory and synaptic plasticity impairment following global ischemia in the rat. Brain Res. 2012;1452:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Reeves WB, Ramesh G. Netrin-1 increases proliferation and migration of renal proximal tubular epithelial cells via the unc5b receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F723–F729. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90686.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A, Cai H. Netrin-1 induces angiogenesis via a dcc-dependent erk1/2-enos feed-forward mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6530–6535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511011103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarjour AA, Manitt C, Moore SW, Thompson KM, Yuh SJ, Kennedy TE. Netrin-1 is a chemorepellent for oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the embryonic spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3735–3744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03735.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlen P, Furne C. Netrin-1: When a neuronal guidance cue turns out to be a regulator of tumorigenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2599–2616. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Seo I, Seo E, Seo SY, Lee HJ, Park HT. Netrin-1 induces proliferation of schwann cells through unc5b receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:1057–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SW, Correia JP, Sun KLW, Pool M, Fournier AE, Kennedy TE. Rho inhibition recruits dcc to the neuronal plasma membrane and enhances axon chemoattraction to netrin 1. Development. 2008;135:2855–2864. doi: 10.1242/dev.024133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Reeves WB, Pays L, Mehlen P, Ramesh G. Netrin-1 overexpression protects kidney from ischemia reperfusion injury by suppressing apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1010–1018. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadagavadi RK, Wang W, Ramesh G. Netrin-1 regulates th1/th2/th17 cytokine production and inflammation through unc5b receptor and protects kidney against ischemia–reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2010;185:3750–3758. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]