Abstract

The mortality after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is 50%, and most survivors suffer severe functional and cognitive deficits. Half of SAH patients deteriorate 5 to 14 days after the initial bleeding, so-called delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI). Although often attributed to vasospasms, DCI may develop in the absence of angiographic vasospasms, and therapeutic reversal of angiographic vasospasms fails to improve patient outcome. The etiology of chronic neurodegenerative changes after SAH remains poorly understood. Brain oxygenation depends on both cerebral blood flow (CBF) and its microscopic distribution, the so-called capillary transit time heterogeneity (CTH). In theory, increased CTH can therefore lead to tissue hypoxia in the absence of severe CBF reductions, whereas reductions in CBF, paradoxically, improve brain oxygenation if CTH is critically elevated. We review potential sources of elevated CTH after SAH. Pericyte constrictions in relation to the initial ischemic episode and subsequent oxidative stress, nitric oxide depletion during the pericapillary clearance of oxyhemoglobin, vasogenic edema, leukocytosis, and astrocytic endfeet swelling are identified as potential sources of elevated CTH, and hence of metabolic derangement, after SAH. Irreversible changes in capillary morphology and function are predicted to contribute to long-term relative tissue hypoxia, inflammation, and neurodegeneration. We discuss diagnostic and therapeutic implications of these predictions.

Keywords: capillary transit time heterogeneity, delayed cerebral ischemia, edema, microcirculation, subarachnoid hemorrhage, vasospasm

Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is caused by the rupture of a cerebral aneurysm, and the subsequent accumulation of blood in the subarachnoid space.1 The age-standardized incidence of SAH is 6 to 7 per 100,000 citizens per year in most countries, but 20 per 100,000 citizens per year in Finland and Japan.1, 2 Half of the patients are below the age of 55 at the time of their SAH,1 and only half of the SAH patients are alive one month after the bleeding.3 Less than 40% of those who survive a SAH are able to return to their previous occupation, and 44% to 93% of the survivors experience restrictions in instrumental activities of daily living.4 The majority of patients experience impaired memory, executive function, and language function in the months, and in some cases years, after their SAH.4 More importantly, permanent neurocognitive symptoms such as fatigue, depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders affect the quality of life of the majority of SAH survivors.4

Early Brain Injury

The majority of deaths after SAH occur within 2 days of the bleeding.5 The release of arterial blood into the subarachnoid space is accompanied by intense headache and an acute increase in intracranial pressure, often causing intracranial circulatory arrest and loss of consciousness.6, 7 The mechanisms of the resulting early brain injury are dominated by cell death, blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption, and brain edema—see ref. 8 for a comprehensive review. The brain edema is predominantly caused by extravasation of plasma across a leaking BBB (vasogenic edema): Animal models show BBB disruption as early as 30 minutes after cortical SAH,9 and the leakage of large molecules remains high within the first 48 hours of the bleeding, after which it normalizes in some species—see ref. 10 and Table 2 therein. In humans, increased blood–brain barrier permeability to diagnostic contrast agents9, 11 and radiographic signs of global edema12 can be observed within 5 to 6 days of the SAH. Studies using diffusion-weighted MRI confirm the formation of diffuse edema acutely after SAH in animal models13 and within the first week in SAH patients.14 Importantly, radiographic signs of global edema based on computerized tomography during hospitalization is an independent predictor of death, severe disability, and poor cognitive outcome at 3-month follow-up.12, 15

Delayed Cerebral Ischemia

Despite appropriate treatment of the ruptured aneurysm, as many as half of the SAH patients develop reduced levels of consciousness and/or focal neurologic deficits 5 to 14 days after the initial bleeding, so-called delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI).1 The symptoms are poorly localized and develop gradually over hours, suggesting a progressing, global disease process.16 The development of ischemic damage often coincides with the emergence of vasospasm—widespread constrictions throughout the cerebrovasculature.17

Causes of Vasospasm: Vessel Responses to Subarachnoid Blood and Blood Breakdown Products

After the release of blood into the subarachnoid space in humans, immune cells infiltrate the meninges within hours, and erythrocytes are gradually removed by phagocytosis and hemolytic breakdown.18 Powerful vasoconstrictors such as thromboxane, endothelin-1, serotonin, platelet-activating factor, and 20-hydoxyeicosatetraenoid acid are hence found in increased levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) after the hemorrhage.19, 20 Endothelin-1 has received special attention in that the combination of oxyhemoglobin (HgbO) and endothelin-1 can elicit ischemia and spreading depolarizations (SDs),21 an important feature of human DCI.22 Spreading depolarizations are self-propagating tissue depolarizations associated with cessation of synaptic activity, surges of extracellular potassium, opening of the BBB with edema formation,23 tissue hypoxia,24 and inversion of the normal CBF responses to neuroglial activity.21

Hemolysis peaks after approximately 1 week,18 and the period of the most intense angiographic vasospasms thus coincides with peaking levels of HgbO in the subarachnoid space in both humans18 and primates.25 Studies have shown that hemoglobin breakdown products can affect vessel tone in several ways—see refs. 18 and 26 for detailed reviews. First, the spontaneous autoxidation of HgbO to methemoglobin, and the iron released from hemoglobin, cause the release of highly reactive superoxide radicals.18, 26 Superoxides are thought to cause vasoconstriction by depleting vascular nitric oxide (NO) levels22, 27 and to cause lipid peroxidation, which in turn causes vasoconstriction and structural damage to the cerebral arteries, including the endothelial cell layer.28 Second, the breakdown of heme into bilirubin under such oxidative conditions results in the formation of bilirubin oxidation products that change the contractility, signaling, and metabolism in large vessels—see ref. 29 for a review. Bilirubin is produced during the time period associated with DCI, and CSF levels of bilirubin oxidation products are higher in patients who develop DCI than in those who do not.30 Third, HgbO has very high affinity for the NO and acts as a sink for this vasodilator.18 Finally, NO production is reduced after SAH, first as neuronal nitric oxide synthetase disappears from nerve fibers in the arterial adventitia,31 and later, when elevated levels of asymmetric dimethyl arginine inhibit the activity of endothelial NOS.32 These reductions in NOS availability and activity have been shown in relation to the development of vasospasm in animal models31 and patients,33 respectively.

The Relation between Vasospasm and Delayed Cerebral Ischemia

Delayed cerebral ischemia and SD may develop in the absence of angiographic vasospasm, just as angiographic vasospasms may resolve without causing ischemic lesions.17, 34, 35 Disappointingly, treatment with clazosentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist that effectively resolves angiographic vasospasms, has failed to reduce mortality, DCI-related morbidity, or functional outcome in relation to SAH.36, 37, 38 It is now believed that vasospasms, rather than causing ischemic damage in their own right, render brain tissue vulnerable to the development of SD which, in turn, cause ischemic lesions—the so-called Double Hit Model of DCI.39 According to this model, the initial bleeding causes generalized macro- and microvascular vasospasm (first hit), whereas the ensuing spreading depressions and further vasoconstrictions cause a critical energy depletion that result in irreversible ischemic damage (second hit).40 The presence of SD indeed correlates with the development of DCI in animal models of SAH and in SAH patients,40, 41 and the inversion of normal arteriolar responses (to elicit vasoconstriction rather than vasodilation) during SD was recently attributed to increased Ca++ oscillations in astrocytes, caused by the presence of blood degradation products.40, 42 The combined increase in perivascular K+ concentration in relation to hemolysis,39 elevated K+ efflux from astrocytic endfeet, and further K+ efflux during SD, are thought to elevate K+ concentrations above a critical threshold at which vascular responses are inverted.37

Long-Term Brain Atrophy

The origin of the long-term cognitive symptoms after SAH remains poorly understood.4 Studies that have compared cognitive outcome scores with lesion location after SAH, suggest that the loss of some aspects of executive function can be ascribed to ischemic lesions in specific brain regions.43 Meanwhile, studies performed 1 year after SAH find ventricular dilation and sulcal enlargement that suggest general atrophy.44 Importantly, outcome and neuropsychological scores after SAH appear to correlate with total atrophy,44, 45 cortical atrophy,46 and hippocampal atrophy.47 The long-term structural and neuropsychological effects of SAH therefore resemble those of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression.47

The Metabolic Role of Change in Capillary Morphology and Pericapillary Edema after Subarachnoid hemorrhage

The complex pathophysiology of SAH raises several questions, which we attempt to address from the perspective of changes in the capillary circulation below: Why did clazosentan, a drug that not only restores vessel diameters in angiographic vasospasm, but also restores cerebral blood flow (CBF) to values above the ischemic thresholds,48 fail to improve patient outcome? What are the roles of BBB damage and tissue edema in the development of DCI—if any? Can changes in the morphology and function of capillaries reviewed below contribute to the development of DCI, and to the risk of long-term, diffuse atrophy and poor neuropsychological outcome?

We recently showed that the availability of oxygen in brain tissue depends not only on the CBF, but also on the microscopic distribution of the blood, the so-called capillary transit time heterogeneity (CTH).49 By a model that determines the availability of oxygen in tissue for a given CBF, CTH, and tissue oxygen tension, we have analyzed the metabolic effects of gradual increases in CTH, which we expect to parallel changes in capillary morphology in ageing and disease.50, 51 We found that as CTH increases, oxygenated blood is increasingly shunted through the capillary bed. To maintain sufficient oxygen availability to support neuronal function and survival, we showed that the vasculature must attenuate CBF responses (and ultimately resting CBF) to improve blood–tissue oxygen concentration gradients and blood–tissue oxygen exchange times. The resulting vascular oxidative stress and tissue hypoxia, however, comes at the expense of increased thrombogenicity, tissue inflammation, and neurodegenerative changes, which we have proposed may have a role in the etiopathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease51 and ischemia–reperfusion injury.50

Below, we review the changes in the capillary morphology and function that are known or likely to occur in relation to SAH, and how any accompanying changes in CTH may interfere with oxygen availability and tissue microenvironment in the various phases of disease progression after SAH.

Changes in Capillary Morphology and Blood–Brain Barrier Function after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

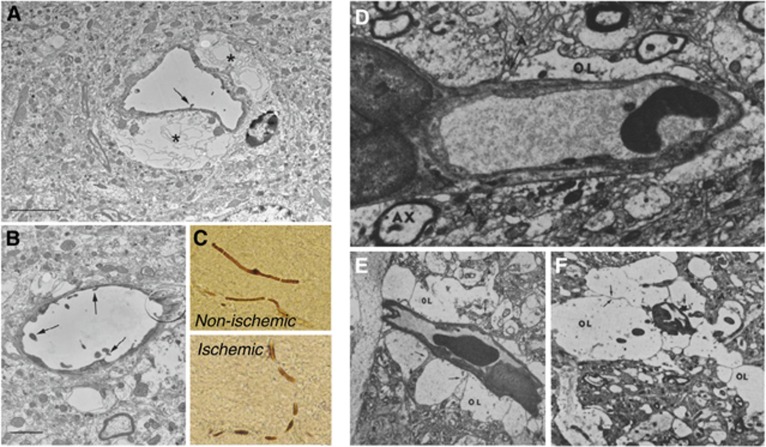

Sehba and Friedrich52 recently reviewed the molecular and morphologic changes that occur in the capillary wall in relation to SAH. These changes involve the development of luminal endothelial protrusions that are thought to restrict capillary flows, and swelling of astrocytic endfeet that cause compression of the capillary lumen—see Figures 1A and 1B. In addition, cerebral ischemia has been shown to result in the constriction of cerebral pericytes, seemingly due to the increased levels of oxidative and nitrosative stress53, 54—see Figure 1C. Experimental studies have shown profound damage to both capillary basement membrane and endothelial cells, followed by disruptions of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and development of vasogenic edema in both experimental ischemia and SAH.55, 56 These changes are paralleled by openings of tight junctions between capillary endothelial cells in models of SAH,9, 52 and likely to be exacerbated by SDs, during which swelling of astrocytic endfeet24 and BBB breakdown23 occur.

Figure 1.

Changes in the capillary morphology after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), ischemia, and hypotonic hyponatremia. Panels A and B show swelling of astrocytic endfeet (*) and endothelial protrusions (arrows) after SAH. Scale bars indicate 5 μm in panel A and 2 μm in panel B, respectively. Reproduced from ref. 52 with permission from the publisher. Panel C shows segmental narrowing of capillaries due to capillary constrictions after ischemia and reperfusion (bottom) compared with slender, thread-like, horseradish peroxidase-filled capillaries in the normal hemisphere (top). Reproduced from ref. 53 with permission from the publisher. Panels D and E show tangential sections through capillaries in sham-operated brain (D) and in a hypotonic hyponatremic edema model (E) in rabbit. The distended astrocytic endfeet (OL), the membranes of which are marked by arrows, clearly compress the capillary lumen, as shown in the transverse section (F). Other astrocytic membranes are labeled ‘A', and axons ‘AX'. The magnifications were × 6500 (D and E) and × 5000 (F), respectively. Reproduced from ref. 59 with permission from the publisher.

Up to 57% of SAH patients develop hypovolemic hyponatremia in the week after the initial bleeding.57 The effects of hyponatremia on cerebral and pericapillary swelling in humans remain unclear, but animal models of osmotic brain edema induced by hyposmotic hyponatremia (intraperitoneal or central venous injection of distilled water) show both brain swelling58 and capillary compression owing to profound swelling of astrocytic endfeet59—see Figures 1D–1F.

Exposure of Capillaries to Vasoactive Substances after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

In the absence of lymphatic vessels, interstitial fluid and solutes from brain parenchyma are removed along the basement membranes of arteries and capillaries to the cervical lymph nodes.60 Recent studies of the clearance of solutes from the CSF in mice show that after intracisternal injection, molecules in the size range 3 to 2,000 kDa distribute rapidly along penetrating arteries into brain tissue, along the basement membranes of arterioles and capillaries, after which they drain into the cervical lymph nodes.61 The molecular weight of the hemoglobin tetramer falls within this size range (64 kDa), and reports on the distribution of horseradish peroxidase62 (44 kDA) and albumin (66 kDa)63 confirm that hemoglobin and its breakdown products are likely to be cleared from the subarachnoid space via perivascular transport to the cervical lymph nodes. The clearance of CSF and interstitial fluid may be disturbed after SAH, but animal studies in which the cervical lymph drainage has been blocked suggest that the perivascular pathway is active and crucial for fluid drainage after SAH.64, 65 It is therefore likely that not only smooth muscle cells, but also pericytes, are exposed to high concentrations (similar to or above those found in CSF) of hemoglobin and other vasoactive substances as these are transported through the narrow basement membranes in which these contractile cells are embedded.61

The control of pericyte tone remains much less studied than that of arterioles.66 The vasoactive substances released after SAH are likely to interfere with both arteriolar and pericyte tone. In vitro experiments suggest that NO acts as a pericyte dilator67, 68 whereas the oxidative and nitrosative stress that result from the release of superoxide radicals have been shown to cause pericyte constrictions in vitro53 and in vivo.53 Furthermore, brain pericytes express endothelin-1 receptors,69 and in vitro studies suggest that pericytes and capillaries constrict upon endothelin-1 exposure.70, 71 The period of maximum vasospasm in cerebral resistance vessels is therefore likely to coincide with a period of poor vascular control, or even constrictions, throughout the capillary bed. In the section below, we describe how any resulting changes in capillary flow patterns can affect tissue oxygenation, independent of any vasoconstrictions at either the arteriolar or arterial level.

The Relation between Erythrocyte Velocities and Oxygen Extraction in Capillaries

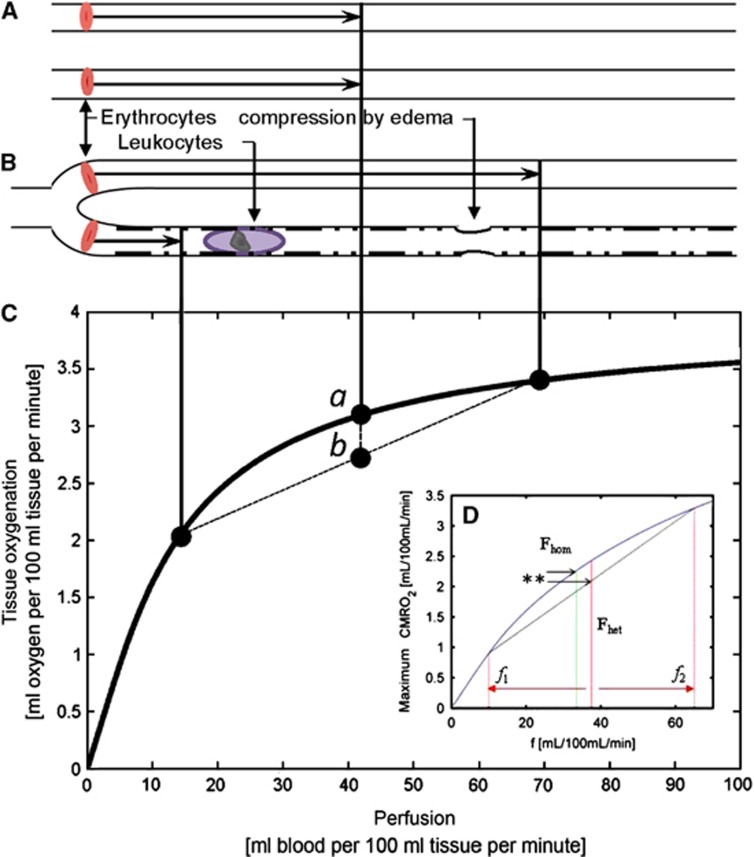

Figure 2 illustrates how the heterogeneity of erythrocyte velocities, as it occurs either naturally or because of the disturbances in the capillary wall or in blood cell morphology, reduces the efficacy of oxygen extraction from blood. As illustrated by the figure, both white blood cell and erythrocyte dimensions exceed the average capillary diameter, and these cells must therefore undergo deformation to enter and pass the capillaries. Changes in the adhesion of blood cells to endothelium have been shown in SAH,73 and such changes are known to disturb capillary flow patterns and lead to 'shunting' of erythrocytes through the capillary bed.74 Studies by direct microscopy in animals,75, 76 and by perfusion MRI in human stroke,77, 78, 79 confirm that capillary flow patterns undergo profound changes in cerebral ischemia.

Figure 2.

The relation between blood flow and net oxygen extraction in single capillaries. The curve in plot C shows the so-called flow–diffusion equation72 for oxygen, that is, shows the maximum amount of oxygen that can diffuse from a single capillary into tissue, for a given perfusion rate. The curve shape predicts three important properties of parallel-coupled capillaries: First, the curve slope decreases towards high-perfusion values, making vasodilation increasingly inefficient as a means of improving tissue oxygenation towards high-perfusion rates. Second, if erythrocyte flows differ among capillary paths (case B) instead of being equal (case A), then net tissue oxygen availability declines. This can be observed by using the curve to determine the net tissue oxygen availability resulting from the individual flows in case B. The resulting net tissue oxygen availability is the weighted average of the oxygen availabilities for the two flows, labeled b in the plot. Note that the resulting tissue oxygen availability will always be less than that of the homogenous case, labeled a. Conversely, homogenization of capillary flows during hyperemia has the opposite effect, and serves to compensate for the first property. By a similar argument, insert D disproves the traditional assumption that increased perfusion always results in improved tissue oxygenation:49 By increasing tissue perfusion from Fhom to Fhet, and again subdividing capillary flows in the latter case into f1 and f2, tissue oxygen availability in fact decreases in response to a flow increase, as indicated by the double asterisk. Note that, if erythrocyte flows are hindered (rather than continuously redistributed) along single capillary paths (as indicated by slow-passing white blood cell (WBC) and/or rugged capillary walls), upstream vasodilation is likely to amplify the redistribution losses, as erythrocytes are forced through other branches at very high speeds, with negligible net oxygenation gains. Reproduced from refs. 49 and 50.

The Combined Effect of Cerebral Blood Flow, Capillary Transit Time Heterogeneity, and Tissue Oxygen Tension on Brain Oxygenation

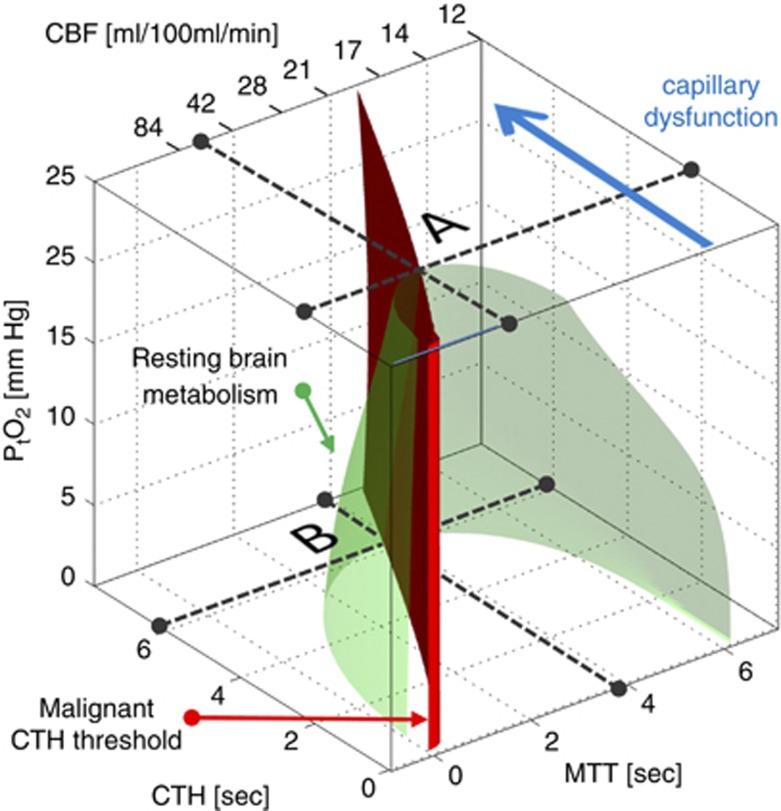

Figure 3 shows how blood mean capillary transit time (MTT), CTH, and tissue oxygen tension (along the three axes) in combination can secure sufficient oxygen to support normal brain function—see also ref. 50. Mean capillary transit time (MTT) is given by the central volume theorem81 as the ratio between capillary blood volume and CBF, which is shown in the secondary x-axis for convenience. The green surface show all combinations of MTT (or CBF), CTH, and tissue oxygen tension that make 2.5 mL oxygen available to each 100 mL of tissue per minute. This rate of oxygen delivery matches the metabolic need of resting brain tissue,80 and the interior of the green half-cone therefore represents hemodynamic conditions that can support normal brain function.

Figure 3.

Metabolic thresholds. The green iso-contour surface corresponds to the metabolic rate of contralateral tissue in patients with focal ischemia.80 The red plane marks the boundary, left of which vasodilation fails to increase tissue oxygen availability (malignant capillary transit time heterogeneity (CTH)). The maximum value that CTH can attain at a tissue oxygen tension (PtO2) of 25 mm Hg, if oxygen availability is to remain above that of resting tissue, is indicated by the label A. As CTH increases further, a critical limit is reached as PtO2 approaches 0—label B. At this stage, the metabolic needs of tissue cannot be supported unless mean transit time (MTT) is prolonged to a threshold of approximately 4 seconds, corresponding to cerebral blood flow (CBF)=21 mL/100 mL/minute. Modified from ref. 50.

The figure illustrates why, theoretically, reductions in tissue oxygen tension and resting CBF are the only alternatives to immediate tissue damage if CTH increases uncontrollably. Label A in Figure 3 shows the theoretical maximum for the increase in CTH (indicated by a broken line parallel to the MTT and CBF axes) that brain tissue can sustain at the tissue oxygen tension of normal brain tissue (25 mm Hg)82 before neurologic symptoms ensue. As CTH approaches this limit, oxygen availability gradually approaches the tissue consumption, causing tissue oxygen tension to decrease.50 At lower tissue oxygen tensions, the green cone is wider, and tissue can therefore accommodate increases in CTH until oxygen tension cannot be reduced further (label B). Note that as CTH increases, CBF must be attenuated (MTT prolonged) to meet the metabolic needs of the tissue. As CTH reaches this maximum and tissue oxygen tension becomes negligible, CBF is predicted to approach 21 mL/100 mL/minute. So, if CBF is indeed adjusted to optimize brain oxygenation as capillary flow patterns become increasingly disturbed, CBF values would therefore be predicted to be close to the classic ischemic threshold of 20 mL/100 mL/minute83 when symptoms arise. Accordingly, this threshold may not only be characteristic of vascular narrowing/occlusion, but also of CBF adaptations to secure sufficient oxygenation under conditions of critically elevated CTH, caused by changes in the capillary flow patterns.50

The Dynamics of Cerebral Blood Flow, Cerebral Blood Flow Responses, and Oxygen Extraction Fraction as Capillary Transit Time Heterogeneity Increases: The Three Stages

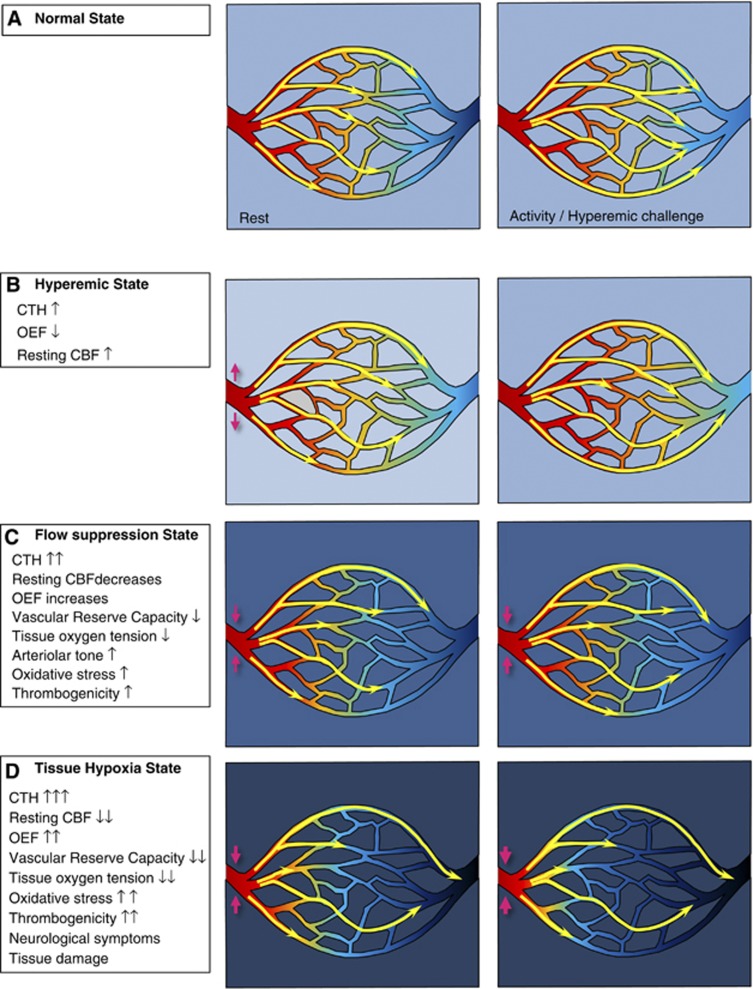

Figure 4A illustrates the dynamics of capillary flow patterns during rest and during increased metabolic needs in the normal brain. The flux of erythrocytes through the cortical brain capillaries is highly inhomogeneous during rest,84, 85, 86 and the limited increase in net extraction of oxygen as flow in individual capillaries is increased (cf. Figure 2D) therefore contribute to the modest (30%) net oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) in the resting brain.49 A range of CBF-modifying stimuli cause parallel homogenizations of capillary flow patterns, including functional hyperemia,49 hypocapnia,87 hypercapnia,88 and hypoxemia.89 We recently showed that the combined reductions in MTT and CTH during functional hyperemia seemingly ensure close coupling of oxygen availability to the metabolic needs of the tissue by this additional, neurocapillary coupling.49

Figure 4.

The subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) stages. The yellow arrows indicate flow with different velocities through the capillary system. The color within the vessels indicates oxygen saturation, and the background color outside the tissue oxygen tension. (A) The normal state, (B) the hyperemic state, where slight capillary transit time heterogeneity (CTH) increases lead to increased cerebral blood flow (CBF). (C) The flow suppression state. (D) Tissue hypoxia. OEF, oxygen extraction fraction.

Mild Capillary Transit Time Heterogeneity Increase: The Hyperemic Stage

Figure 4B illustrates the metabolic consequence of capillary dysfunction: disturbances that elevate flow heterogeneity, and prevent the normal flow homogenization during hyperemia. Elevated CTH reduces the OEF that can be attained for a given tissue oxygen tension,49 and the metabolic needs of tissue can therefore be met by slight increases in CBF, both during rest and during hyperemia (e.g. functional activation or hypercapnia). We therefore refer to states of mild CTH increases as hyperemic.

Increases in the blood flow velocity in the intracranial vessel are indeed observed in the days after SAH in both animal models90 and patients91 by transcranial Doppler sonography (TCD). Increased flow velocities may, in principle, be caused by either or both relative vasoconstriction and increased CBF.92 Parallel recordings of arteriovenous oxygen differences and TCD flow velocities in the first days after SAH, however, show decreased OEF during the gradual increase in flow velocity, consistent with such relative hyperemia.93 Similarly, direct measurements of CBF show occasional hyperemia and early reductions in OEF in patients after SAH.94 The molecular underpinnings of the early vasodilation after SAH have been explored in animal models: within the first few days of SAH, the production of NO indeed appears to be upregulated in the walls of pial arterioles (in contrast to the subsequent downregulation reviewed above), as evidenced by increased expression of endothelial endothelial NOS and increased levels of NO breakdown products.95

Moderate Capillary Transit Time Heterogeneity Increase: The Flow Suppression Stage

As changes in capillary or blood morphology accumulate and CTH increases further, increases in CBF can no longer compensate for the parallel reduction in OEFmax. The slope of the curve that depicts oxygen extraction as a function of blood flow (cf. Figure 2C) becomes more and more horizontal towards high-flow values, indicating that, as resting CBF increases, (additional) hyperemia becomes increasingly inefficient as a means of increasing oxygen availability during episodes of increased metabolic needs. As indicated by the insert in Figure 2D, CTH can become so high that increases in CBF no longer increase oxygen availability. Note that, in the absence of a mechanism that blocks further vasodilation in cases where this fails to improve tissue oxygenation, a state of high CTH is predicted to lead to uncontrolled hyperperfusion and hypoxic tissue damage, such as it is observed in the luxury perfusion syndrome.96 This phenomenon, and reperfusion injury, is discussed further in refs. 49 and 50. Our analysis shows that, provided CBF is suppressed, the resulting reduction in tissue oxygen tension improves blood–tissue concentration gradients and OEFmax so much that oxygenation for brain function can be secured.49 The prediction that the cerebral vasculature attempts to suppress any CBF increases is consistent with the finding that vasodilatory responses, referred to as the cerebrovascular reserve capacity, are reduced between days 3 and 13 in patients with SAH.97

The Hypoxic Stage: Short-Term Tissue Damage or Long-Term Neurodegeneration.

If CTH increases even further, the reduction of tissue oxygen tension can contribute to tissue damage in several ways. First, the reduction of tissue oxygen tension is likely to increase the probability of devastating SDs.40 Second, the reduction of tissue oxygen tension activates hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs). Increased HIFs-1 levels is a powerful stimulus for BBB opening and edema formation in SAH,98 contributing to the vicious cycle of further CTH increase and hypoxia as indicated in Figure 5. Third, HIF-1 also upregulates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2 levels,99 the main source of reactive oxygen species in SAH.100 Reactive oxygen species reacts with NO to form peroxynitrite.101 Although NO depletion and peroxynitrite both cause vasoconstriction by impairing normal smooth muscle cell relaxation,102 peroxynitrite also inactivates tissue plasminogen activator, increasing thrombogenicity, and thereby the risk of further tissue damage.103 The latter is consistent with the recent demonstration that the extent of microthrombosis correlates with low levels of NO in models of SAH.104 Microvascular constrictions and microthrombosis have been demonstrated within 3 hours of experimental SAH,105 suggesting that flow suppression, and possibly relative tissue hypoxia may be present early after SAH, possibly in relation to pericyte constrictions and early BBB opening. Finally, hypoxia and peroxynitrite are also known to damage mitochondria.102 Mitochondrial dysfunction, in turn, exacerbates the energy crisis by reducing the amount of ATP that can be obtained from the available oxygen, and amplifies the production of ROS.102

Figure 5.

The figure summarizes the pathways from the acute subarachnoid hemorrhage to early brain injury (EBI), delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI), and the long-term degenerative changes that are hypothesized to be the result of irreversible increases in capillary transit time heterogeneity (CTH). Nitric oxide synthetase (NOS) dysfunction refers to the loss of neuronal nitric oxide synthetase (nNOS) from nerve fibers in the arterial adventitia, and the inhibition of endothelial NOS (eNOS) by asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA)—see text. The blue arrows indicate ‘vicious cycles' through which low oxygen tension exacerbates blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption and capillary flow disturbances. The green text boxes indicate possible sites of therapeutic intervention discussed in the text. HgbO, oxyhemoglobin; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SD, spreading depolarizations.

If CTH continues to increase, our model of oxygen availability predicts that oxygen reserves are exhausted as tissue oxygen tension become negligible and CBF approaches 21 mL/100 g/minute. This is consistent with global CBF values in patients who develop DCI, reported to range from 17 to 21 mL/100 mL/minute in some,48, 94, 106 and up to 30–40 mL/100 mL/minute in others.107, 108, 109

If, however, (i) perivascular HgbO clearance is completed without causing critical capillary flow disturbances owing to the parallel NO depletions, (ii) capillary edema formation eventually becomes outbalanced by the normal resorption and removal of pericapillary fluid, and (iii) endothelial, basement membrane, pericyte, and astrocyte endfeet morphology and function normalize (cf. Figure 1), then the increase in CTH is predicted to halt and potentially reverse. The additive effect of these factors, and their approximate time-scale, are illustrated by Figure 5B. According to this scenario, the reversal of hypoperfusion and angiographic vasospasm in SAH is hence in part the result of a gradual normalization of capillary flow patterns.

The extent to which the profound changes in the capillary wall morphology in relation to SAH are indeed reversible remains unclear. If not, residual CTH elevations are predicted to render tissue relatively hypoxic. Chronic hypoxia is associated with upregulation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-1 and nuclear factor NF-κB, a strong inflammatory signal110 that might account for the acute and chronic inflammatory changes after SAH recently reviewed by Provencio.73 The putative pathway from chronically elevated CTH to neurodegeneration is discussed in detail in ref. 51 The notion that the neurovascular changes in SAH survivors are permanent is supported by findings that their cerebrovascular reserve capacity in many cases remain low,111, 112 suggestive of persisting CTH elevation characteristic of the flow suppression stage described in Figure 4C.

Discussion

The recent revision of the classic flow–diffusion equation to take the heterogeneity of the capillary flow patterns into account49 implies that factors such as vasogenic edema, astrocytic endfeet swelling, and NO depletion during the pericapillary clearance of blood, may have profound implications for cerebral oxygenation after SAH. The analysis in this review suggests that the pathway from aneurysmal hemorrhage to DCI can be explained in part by adaptations to the increases in CTH that result from these factors—and that the degree of long-term neurodegenerative changes is determined by the extent to which these factors are reversible. An overview of the hypothesized chain of events is shown in Figure 5.

The additive effect of capillary NO depletion and (cytotoxic and vasogenic) edema in terms of the CTH increase, vasospasm (micro- and/or macrovascular, angiographic), and clinical deterioration after SAH is illustrated in Figure 6. The relative importance of edema formation may be gleaned from the puzzling difference in the outcome in clot-placement and filament-puncture models of SAH: in the former, little BBB damage and edema are detected, and little if any mortality or poor functional outcome is observed.113 In the latter, however, extensive BBB damage and edema develops, and the rates of mortality and neurologic and long-term cognitive deficits seemingly resemble those found in patients. Brain edema thus appears to contribute to the poor long-term outcome after SAH, while NO depletion during the perivascular clearance of blood breakdown no doubt contributes to the deterioration during days 6 to 12. Further evidence in support of CTH as an indicator of metabolic derangement after SAH is offered by the finding that leukocyte counts during the first 5 days after SAH seemingly predicts clinical deterioration, the development of angiographic vasospasm,114 and death.115 Increased number and endothelial adhesion of leukocytes are known to disturb capillary flow patterns and lead to 'shunting' of erythrocytes through the capillary bed.74 Leukocytosis after SAH is thought to reflect endogenous catecholamine release, and after control for the use of steroids and other known predictors of the development of angiographic vasospasm, the peak number of lymphocytes 1 to 5 days after admission has been shown to be an independent predictor of the development of angiographic vasospasm.116

Figure 6.

Panel A summarizes the sources of capillary flow disturbances as identified in this review, and their estimated duration. They include the oxidative stress and nitric oxide (NO) depletion caused by pericapillary oxyhemoglobin, structural damage to the capillary wall (including endothelial cells, basement membranes, pericytes, and astrocytic endfeet), leukocytosis, and compression by pericapillary edema. The extent to which the structural damage to the capillary wall is permanent remains crucial in that permanent changes in capillary transit time heterogeneity (CTH) are potential sources of long-term, neurodegenerative changes. Panel B indicates the added effect of the changes in panel A in terms of the resulting change in CTH over time. The time of the peak CTH change is likely to coincide with the peak pericapillary oxyhemoglobin HgbO concentration, whereas the height of the peak is likely to correlate with the size of the hematoma. The extent to which one observes flow increases by transcranial Doppler sonography (TCD), angiographic vasospasm, or tissue lesions by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is predicted to depend on the individual sizes of the factors in panel A. Note that large hematomas are likely to generate large net CTH increases owing to their larger, net capillary NO depletion, and thus to result in both angiographic vasospasm and hypoxic lesions.

Diagnostic Implications

The model predicts that the progression of increased flow velocity on TCD (hyperemic stage) only in the most severe cases develop into angiographic vasospasm (flow suppression stage), and that neurologic symptoms or permanent tissue damage only develop if these adaptation fails to maintain tissue metabolism during the period of pericapillary edema (hypoxic stage and beyond). See Figure 6. This is consistent with the reports that increased flow velocities by TCD is a more frequent finding than angiographic stenosis, which again is more frequent than clinical and/or radiologic signs of insufficient tissue oxygenation in SAH patients.117 The finding that both elevated flow velocities by TCD, and angiographic vasospasm, correlate poorly with any aspects of patient outcome is in agreement with the prediction that these radiologic findings reflect early adaptations to preserve tissue oxygen availability in a condition of progressive microvascular failure. In contrast, clinical deterioration and radiologic signs of tissue infarction are predicted to reflect the exhaustion of such compensatory mechanisms. This is consistent with the findings that only radiologic signs of infarction seemingly correlate with reduced instrumental activities of daily living, cognitive impairment, and poor quality of life 3 months after the SAH.117

The considerations above suggest that it may be of both diagnostic and prognostic value to monitor CTH and MTT in SAH patients. Capillary transit time heterogeneity and MTT can be measured by monitoring the clearance of intravascular contrast agents as part of standard perfusion-weighted MRI, perfusion CT, or contrast-enhanced transcranial ultrasound examinations.77, 118, 119, 120

Therapeutic Implications

The hypothesis put forward suggests that the angiographic vasospasm that precede DCI is in part secondary to disturbances in capillary flow patterns—and predicts that normalization of vascular tone and CBF may do little to improve tissue oxygenation because of the level of capillary shunting. This is consistent with the disappointing clinical results of resolving angiographic vasospasms,36, 37, 38 although they seemingly partly restore CBF.48 Paradoxically, the increased free radical production and NO depletion in the walls of resistance vessels may in fact improve tissue oxygenation by attenuating CBF responses. Although the release of free radicals is a well-established source of tissue damage after SAH,121 its hypothesized beneficial effects in the maintenance of tissue oxygenation may explain the conflicting results of anti-oxidant therapy in SAH.121 Below, we briefly discuss therapeutic interventions that might reverse or counteract capillary constriction and compression in the acute stages of SAH.

Management of Pericapillary Edema

Until recently, the hemodynamic management of patients with clinical signs of vasospasm aimed to achieve systemic hypertension, hypervolemia, and hemodilution—so-called triple-H therapy.122, 123 This approach is based on the assumption that augmented cardiac output and blood pressure by vasopressors and isotonic fluids help maintain CBF, cerebral microcirculation, and thereby brain oxygenation.122, 123 The extent to which each of the three components of triple-H therapy prevents DCI remains uncertain.124 In some cases, hypervolemia and hemodilution are associated with side effects including cerebral edema, cardiac failure, and electrolyte abnormalities.124 Experimental studies suggest that alpha-adrenoreceptor stimulation may increase BBB permeability,125 and in patients with SAH, the use of vasopressors is independently associated with the development of global cerebral edema.12 Although some clinicians recommend the use of triple-H therapy in some instances,126 others have abandoned the principles of triple-H therapy,123, 127 and recent guidelines for the management of SAH therefore recommend euvolemia and induction of hypertension for patients with DCI.124

Given the proposed metabolic significance of pericapillary edema after SAH, means of reducing the extravasation of fluids across the BBB may prove beneficial. Contrary to triple-H therapy, the Lund-concept, originally conceived for the management of patients with severe brain trauma,128 aims to reduce intracapillary hydrostatic pressure and maintain colloid osmotic pressure. This approach is thought to increase transcapillary fluid reabsorption and to reduce cerebral edema. In a study including 30 patients with severe brain trauma and 30 SAH patients, therapy based on the Lund-concept showed significantly lower mortality than conventional triple-H therapy.129 Needless to say, this concept must be examined in larger SAH patient cohorts.

Intracranial hypertension in patients with cerebral edema is generally treated with either mannitol or hypertonic saline (HS) according to institutional guidelines. While both agents have been proven efficacious in mixed patient populations, clinical controlled trials non-significantly favor the use of HS in terms of reducing intracranial pressure.130, 131 In addition, the use of mannitol appears to be associated with more adverse events, including hypovolemia, than HS.132 One experimental study specifically compared the use of HS and mannitol in animal models of SAH, and demonstrated that the use of HS was associated with better intracranial pressure control and less neuronal damage.133

The compression of capillaries owing to hyponatremia (cf. Figure 1) might be reversed by means of restoring plasma sodium levels. Hypertonic saline is thought to create a strong transcapillary osmotic gradient that causes a shift of fluid away from brain tissue, interstitium, and endothelial cells, thereby improving the cerebral microcirculation.134 Indeed, the infusion of HS in patients with SAH has been shown to increase both CBF and tissue oxygen tension135—the tell-tale signs of a reductions in CTH, cf. Figure 3. Preliminary data also show improvements in the degree of angiographic vasospasm,136, 137 in CBF,109, 138 and in modified Rankin Scale upon discharge.139 Despite the complexity of managing hyponatremia,57 the apparent safety of HS infusions in neurocritically ill patients140, 141, 142 encourages further experimental and clinical studies.

Restoration of Capillary Nitric Oxide Levels

The ROS production and the NO depletion due to the pericapillary HgbO is likely to increase CTH for as long as hemolysis occurs in the subarachnoid space, unless NO levels at the capillary level can be maintained. When CTH increases and tissue oxygen tension drops, the risk of capillary NO depletion is likely to become more severe, as oxygen is the natural substrate for NO production via NO synthases.66 NO depletion at the capillary level would therefore be expected to fuel a vicious cycle by causing further tissue hypoxia, further attenuation of upstream vessel tone, and so forth.

Endogenous nitrite is converted to NO in the tissue without the need for oxygen as a substrate,143 and the infusion of nitrite might therefore be neuroprotective by preventing NO depletion and ROS production,144, 145, 146 and thereby pericyte constrictions during their exposure to HgbO. By attenuating CTH increases, nitrite infusions might therefore improve oxygen delivery to tissue during this critical phase. Furthermore, nitrite reduces mitochondrial proton leakage, increasing ATP yields from oxygen and thereby tissue tolerance to hypoxia.147 Nitrite may also attenuate thrombogenicity by inhibiting platelet aggregation.148 Early administration of nitrite has been shown to prevent vasospasm after SAH149, 150 and to increase tissue survival in ischemia–reperfusion151 in primate animal models. The prolonged administration of nitrite to healthy volunteers is deemed safe,152 and a recent phase II trial confirmed that sodium nitrite salt is safe to administer to SAH patients throughout the critical phase after SAH.153

Stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion has been shown to reduce angiographic vasospasm and increase CBF in dogs154 and monkeys155 after experimental SAH. Fibers from the sphenopalatine ganglion release NO,156, 157 acetylcholine, and a range of vasoactive peptidergic neurotransmitters in the adventitia of cerebral vessels, causing vasodilation.158 The effects of sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation remains to be examined in SAH patients, but it is interesting to note that NO releasing nerve fibers are present at both the arterial and capillary level.159 Although neuronal NOS is lost in sphenopalatine nerve fibers at the arterial level after SAH,31 our hypothesis suggests that activation of capillary NO production by this route may be of benefit after SAH.

Management of Blood Viscosity and Tissue Microcirculation

Increased numbers and endothelial adhesion of leukocytes are known to disturb capillary flow patterns,74 and means of reducing the number of circulating leukocytes and their adhesion to capillary endothelium would therefore be predicted to reduce CTH, and thereby to reduce angiographic vasospasm and DCI after SAH. Ishikawa et al160 indeed found increased adhesion and rolling of leukocytes, paralleled by a 60% reduction in CBF, after experimental SAH in mice, and demonstrated that these changes could be reversed by inhibiting the endothelial cell adhesion molecules. For a comprehensive review of the role of leukocyte–endothelial interactions after SAH, see ref. 161. Corticosteroid treatment is a well-known cause of leukocytosis in humans. Although corticosteroid treatment prevents hyponatremia162 and may attenuate edema in SAH patients, we speculate that the detrimental effects of leukocytosis on tissue oxygenation may obscure the translation of such beneficial effects into better patient outcomes.162, 163

Statin treatment of SAH patients has attracted considerable interest after reports that treatment with statins before SAH reduces the loss of vascular endothelial NOS in animal models164 and ameliorates DCI and angiographic vasospasm in patients,165 and that statin treatment upon admission reduces mortality after SAH.166 Subsequent studies have yielded conflicting results, with high-dose statin treatment in animal models showing a definite neuroprotective effect, whereas studies in SAH patients remain inconclusive.167, 168 In addition to its effects of endothelial function, statins also reduce blood viscosity by lowering blood lipid levels, and would therefore be expected to facilitate the capillary passage of blood and thus reduce CTH. The lipid-lowering effect of statins becomes significant 2 to 4 days after initiation of treatment in normocholesterolemic subjects,169 and improved blood viscosity could therefore contribute to a protective effect in the days after SAH. The relative contribution of plasma lipids to total blood viscosity may, however, vary relative to that of leukocytes (see previous section). We speculate that studies of the effect of statins in human SAH must be controlled for the degree of leukocytosis in individual patients. The putative effects of blood viscosity may be most easily disentangled in animal models of SAH, in which concomitant leukocytosis is not a consistent finding.160

Although capillary dilation may be facilitated by restoring pericapillary NO levels, the extent to which capillary constriction can be inhibited remain unclear. Antihypertensives are likely to interfere with both arteriolar and pericyte tone in that pericytes constrict in response to stimulation by β2-adrenergic,170 Angiotensin-II type 1,171, 172 and endothelin-169 receptor agonists via a calcium channel-dependent mechanism. Although ET antagonist treatment is still being explored further, it is interesting to note that nimodipine, a calcium channel blocker that might be expected to prevent pericyte constrictions, has shown some efficacy in preventing DCI after SAH.1, 173

Conclusion

Our review identifies a number of sources of altered capillary morphology and function, both acutely and during the first critical weeks after SAH. Our earlier re-analysis of the classic flow–diffusion equation predicts that any increase in CTH that accompany such changes tends to increase the shunting of oxygenated blood through the capillary bed. Vasospasm and inverted CBF responses may therefore, paradoxically, improve net oxygen extraction when capillary flows are disturbed by pericyte damage, nitric oxide depletion, vasogenic edema, astrocytic endfeet swelling, or leukocytosis. The role of capillary flows after SAH is supported by the results of studies that have aimed to control pericapillary edema or prevent NO depletion.

Our review further suggests that any irreversible changes in the capillary morphology or function can cause long-term degenerative changes and permanent neurocognitive symptoms after SAH.

Needless to say, the predictions and hypotheses presented in this review must be tested in experimental and clinical settings to verify the importance of the microcirculation and of BBB function after SAH. The hypothesized disturbances in CTH must be demonstrated and quantified by invasive or noninvasive approaches, and the theoretical predictions of their metabolic and functional significance assessed by independent techniques. Hopefully, better understandings of the role of capillary function in SAH can contribute to the reduce the mortality and morbidity after this devastating disease.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (CFIN; LØ, RA), the Danish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Education (MINDLab; LØ, RA, AT, JUB, NKI, TSE, EGJ, CC).

References

- van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 2007;369:306–318. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn FH, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, van Gijn J. Incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage: role of region, year, and rate of computed tomography: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 1996;27:625–629. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hop JW, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, van Gijn J. Case-fatality rates and functional outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review. Stroke. 1997;28:660–664. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khindi T, Macdonald RL, Schweizer TA. Cognitive and functional outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2010;41:e519–e536. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.581975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Leach A. Initial and recurrent bleeding are the major causes of death following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1994;25:1342–1347. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.7.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote E, Hassler W. The critical first minutes after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:654–661. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198804000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voldby B, Enevoldsen EM. Intracranial pressure changes following aneurysm rupture. Part 1: clinical and angiographic correlations. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:186–196. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.56.2.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill J, Calvert JW, Zhang JH. Mechanisms of early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1341–1353. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doczi T. The pathogenetic and prognostic significance of blood-brain barrier damage at the acute stage of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Clinical and experimental studies. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1985;77:110–132. doi: 10.1007/BF01476215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germano A, d'Avella D, Imperatore C, Caruso G, Tomasello F.Time-course of blood-brain barrier permeability changes after experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2000142575–580.discussion 580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler MK, Chassidim Y, Lublinsky S, Revankar GS, Major S, Kang EJ, et al. Impaired neurovascular coupling to ictal epileptic activity and spreading depolarization in a patient with subarachnoid hemorrhage: possible link to blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Epilepsia. 2012;53 (Suppl 6:22–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03699.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claassen J, Carhuapoma JR, Kreiter KT, Du EY, Connolly ES, Mayer SA. Global cerebral edema after subarachnoid hemorrhage: frequency, predictors, and impact on outcome. Stroke. 2002;33:1225–1232. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000015624.29071.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orakcioglu B, Fiebach JB, Steiner T, Kollmar R, Juttler E, Becker K, et al. Evolution of early perihemorrhagic changes—ischemia vs. edema: an MRI study in rats. Exp Neurol. 2005;193:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Soppi V, Mustonen T, Kononen M, Koivisto T, Koskela A, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage in the subacute stage: elevated apparent diffusion coefficient in normal-appearing brain tissue after treatment. Radiology. 2007;242:518–525. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiter KT, Copeland D, Bernardini GL, Bates JE, Peery S, Claassen J, et al. Predictors of cognitive dysfunction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2002;33:200–208. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijdra A, Van Gijn J, Stefanko S, Van Dongen KJ, Vermeulen M, Van Crevel H. Delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: clinicoanatomic correlations. Neurology. 1986;36:329–333. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley RW, Medel R, Dumont AS, Ilodigwe D, Kassell NF, Mayer SA, et al. Angiographic vasospasm is strongly correlated with cerebral infarction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2011;42:919–923. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Weir BK. A review of hemoglobin and the pathogenesis of cerebral vasospasm. Stroke. 1991;22:971–982. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi K, Miyata N, Renic M, Harder DR, Roman RJ. Hemoglobin, NO, and 20-HETE interactions in mediating cerebral vasoconstriction following SAH. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R84–R89. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00445.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M, Seifert V.Endothelin and subarachnoid hemorrhage: an overview Neurosurgery 199843863–875.discussion 875-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold GC, Einhaupl KM, Dirnagl U, Dreier JP. Ischemia triggered by spreading neuronal activation is induced by endothelin-1 and hemoglobin in the subarachnoid space. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:591–598. doi: 10.1002/ana.10723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryglewski RJ, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Superoxide anion is involved in the breakdown of endothelium-derived vascular relaxing factor. Nature. 1986;320:454–456. doi: 10.1038/320454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Qiu J, Matsuoka N, Bolay H, Bermpohl D, Jin H, et al. Cortical spreading depression activates and upregulates MMP-9. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1447–1455. doi: 10.1172/JCI21227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano T, Tian GF, Peng W, Lou N, Lovatt D, Hansen AJ, et al. Cortical spreading depression causes and coincides with tissue hypoxia. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:754–762. doi: 10.1038/nn1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluta RM, Afshar JK, Boock RJ, Oldfield EH. Temporal changes in perivascular concentrations of oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:557–561. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.3.0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluta RM. Delayed cerebral vasospasm and nitric oxide: review, new hypothesis, and proposed treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105:23–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey FE, Li XC, Carretero OA, Garvin JL, Pagano PJ. Perivascular superoxide anion contributes to impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation: role of gp91(phox) Circulation. 2002;106:2497–2502. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038108.71560.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Wakai S, Asano T, Watanabe T, Kirino T, Sano K. The effect of a lipid hydroperoxide of arachidonic acid on the canine basilar artery. An experimental study on cerebral vasospasm. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:357–365. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.54.3.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne-Geithman GJ, Nair SG, Stamper DN, Clark JF. Role of bilirubin oxidation products in the pathophysiology of DIND following SAH. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2013;115:267–273. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1192-5_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne-Geithman GJ, Morgan CJ, Wagner K, Dulaney EM, Carrozzella J, Kanter DS, et al. Bilirubin production and oxidation in CSF of patients with cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1070–1077. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluta RM, Thompson BG, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Boock RJ, Oldfield EH. Loss of nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity in cerebral vasospasm. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:648–654. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.4.0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CS, Iuliano BA, Harvey-White J, Espey MG, Oldfield EH, Pluta RM. Association between cerebrospinal fluid levels of asymmetric dimethyl-L-arginine, an endogenous inhibitor of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and cerebral vasospasm in a primate model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:836–842. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.5.0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CS, Lange B, Zimmermann M, Seifert V. The CSF concentration of ADMA, but not of ET-1, is correlated with the occurrence and severity of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosci Lett. 2012;524:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinstein AA, Friedman JA, Weigand SD, McClelland RL, Fulgham JR, Manno EM, et al. Predictors of cerebral infarction in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:1862–1866. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000133132.76983.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woitzik J, Dreier JP, Hecht N, Fiss I, Sandow N, Major S, et al. Delayed cerebral ischemia and spreading depolarization in absence of angiographic vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:203–212. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Higashida RT, Keller E, Mayer SA, Molyneux A, Raabe A, et al. Clazosentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage undergoing surgical clipping: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (CONSCIOUS-2) Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:618–625. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Higashida RT, Keller E, Mayer SA, Molyneux A, Raabe A, et al. Randomized trial of clazosentan in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage undergoing endovascular coiling. Stroke. 2012;43:1463–1469. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.648980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Higashida RT, Keller E, Mayer SA, Molyneux A, Raabe A, et al. Randomised trial of clazosentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage undergoing surgical clipping (CONSCIOUS-2) Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2013;115:27–31. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1192-5_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluta RM, Hansen-Schwartz J, Dreier J, Vajkoczy P, Macdonald RL, Nishizawa S, et al. Cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage: time for a new world of thought. Neurol Res. 2009;31:151–158. doi: 10.1179/174313209X393564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier JP, Ebert N, Priller J, Megow D, Lindauer U, Klee R, et al. Products of hemolysis in the subarachnoid space inducing spreading ischemia in the cortex and focal necrosis in rats: a model for delayed ischemic neurological deficits after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:658–666. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.4.0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier JP, Woitzik J, Fabricius M, Bhatia R, Major S, Drenckhahn C, et al. Delayed ischaemic neurological deficits after subarachnoid haemorrhage are associated with clusters of spreading depolarizations. Brain. 2006;129:3224–3237. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide M, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Wellman GC. Inversion of neurovascular coupling by subarachnoid blood depends on large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E1387–E1395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121359109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinaud O, Perin B, Gerardin E, Proust F, Bioux S, Gars DL, et al. Anatomy of executive deficit following ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:595–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendel P, Koivisto T, Aikia M, Niskanen E, Kononen M, Hanninen T, et al. Atrophic enlargement of CSF volume after subarachnoid hemorrhage: correlation with neuropsychological outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:370–376. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam AK, Ilodigwe D, Li Z, Schweizer TA, Macdonald RL. Global cerebral atrophy after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a possible marker of acute brain injury and assessment of its impact on outcome. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2013;115:17–21. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1192-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendel P, Koivisto T, Niskanen E, Kononen M, Aikia M, Hanninen T, et al. Brain atrophy and neuropsychological outcome after treatment of ruptured anterior cerebral artery aneurysms: a voxel-based morphometric study. Neuroradiology. 2009;51:711–722. doi: 10.1007/s00234-009-0552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendel P, Koivisto T, Hanninen T, Kolehmainen A, Kononen M, Hurskainen H, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage is followed by temporomesial volume loss: MRI volumetric study. Neurology. 2006;67:575–582. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000230221.95670.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth M, Capelle HH, Munch E, Thome C, Fiedler F, Schmiedek P, et al. Effects of the selective endothelin A (ET(A)) receptor antagonist Clazosentan on cerebral perfusion and cerebral oxygenation following severe subarachnoid hemorrhage—preliminary results from a randomized clinical series Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2007149911–918.discussion 918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen SN, Østergaard L. The roles of cerebral blood flow, capillary transit time heterogeneity and oxygen tension in brain oxygenation and metabolism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:264–277. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard L, Jespersen SN, Mouridsen K, Mikkelsen IK, Jonsdottir KY, Tietze A, et al. The role of the cerebral capillaries in acute ischemic stroke: the extended penumbra model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:635–648. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard L, Aamand R, Gutierrez-Jimenez E, Ho Y-L, Blicher JU, Madsen SM, et al. The capillary dysfunction hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1018–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehba FA, Friedrich V. Cerebral microvasculature is an early target of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2013;115:199–205. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1192-5_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yemisci M, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Vural A, Can A, Topalkara K, Dalkara T. Pericyte contraction induced by oxidative-nitrative stress impairs capillary reflow despite successful opening of an occluded cerebral artery. Nat Med. 2009;15:1031–1037. doi: 10.1038/nm.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppiatt CM, Howarth C, Mobbs P, Attwell D. Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes. Nature. 2006;443:700–704. doi: 10.1038/nature05193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholler K, Trinkl A, Klopotowski M, Thal SC, Plesnila N, Trabold R, et al. Characterization of microvascular basal lamina damage and blood-brain barrier dysfunction following subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1142:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon I, Kim EH, del Zoppo GJ, Heo JH. Ultrastructural and temporal changes of the microvascular basement membrane and astrocyte interface following focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:668–676. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee AH, Burns JD, Wijdicks EF. Cerebral salt wasting: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2010;21:339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JE, Banks M, Dimlich RV, Evers J. Blood-brain barrier water permeability and brain osmolyte content during edema development. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:662–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUSE SA, HARRIS B. Electron microscopy of the brain in experimental edema. J Neurosurg. 1960;17:439–446. doi: 10.3171/jns.1960.17.3.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carare RO, Bernardes-Silva M, Newman TA, Page AM, Nicoll JA, Perry VH, et al. Solutes, but not cells, drain from the brain parenchyma along basement membranes of capillaries and arteries: significance for cerebral amyloid angiopathy and neuroimmunology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34:131–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennels ML, Blaumanis OR, Grady PA. Rapid solute transport throughout the brain via paravascular fluid pathways. Adv Neurol. 1990;52:431–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura T, Fraser PA, Cserr HF. Distribution of extracellular tracers in perivascular spaces of the rat brain. Brain Res. 1991;545:103–113. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BL, Xia ZL, Wang JR, Yuan H, Li WX, Chen YS, et al. Effects of blockade of cerebral lymphatic drainage on regional cerebral blood flow and brain edema after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2006;34:227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BL, Xie FM, Yang MF, Cao MZ, Yuan H, Wang HT, et al. Blocking cerebral lymphatic drainage deteriorates cerebral oxidative injury in rats with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;110:49–53. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0356-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Buchan AM, Charpak S, Lauritzen M, Macvicar BA, Newman EA. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature. 2010;468:232–243. doi: 10.1038/nature09613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haefliger IO, Zschauer A, Anderson DR. Relaxation of retinal pericyte contractile tone through the nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:991–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haefliger IO, Anderson DR. Oxygen modulation of guanylate cyclase-mediated retinal pericyte relaxations with 3-morpholino-sydnonimine and atrial natriuretic peptide. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1563–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehouck MP, Vigne P, Torpier G, Breittmayer JP, Cecchelli R, Frelin C. Endothelin-1 as a mediator of endothelial cell-pericyte interactions in bovine brain capillaries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:464–469. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199704000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonfelder U, Hofer A, Paul M, Funk RH. In situ observation of living pericytes in rat retinal capillaries. Microvasc Res. 1998;56:22–29. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam HC, Lee JK, Lu CC, Chu CH, Chuang MJ, Wang MC. Role of endothelin in diabetic retinopathy. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2003;1:243–250. doi: 10.2174/1570161033476600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkin EMBW. Zweifach Award lecture. Regulation of the microcirculation. Microvasc Res. 1985;30:251–263. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(85)90057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencio JJ. Inflammation in subarachnoid hemorrhage and delayed deterioration associated with vasospasm: a review. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2013;115:233–238. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1192-5_42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni MC, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Mechanisms and consequences of cell activation in the microcirculation. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:709–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita Y, Tomita M, Schiszler I, Amano T, Tanahashi N, Kobari M, et al. Moment analysis of microflow histogram in focal ischemic lesion to evaluate microvascular derangement after small pial arterial occlusion in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:663–669. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudetz AG, Feher G, Weigle CG, Knuese DE, Kampine JP. Video microscopy of cerebrocortical capillary flow: response to hypotension and intracranial hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H2202–H2210. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.6.H2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard L, Sorensen AG, Chesler DA, Weisskoff RM, Koroshetz WJ, Wu O, et al. Combined diffusion-weighted and perfusion-weighted flow heterogeneity magnetic resonance imaging in acute stroke. Stroke. 2000;31:1097–1103. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen CZ, Rohl L, Vestergaard-Poulsen P, Gyldensted C, Andersen G, Østergaard L. Final infarct size after acute stroke: prediction with flow heterogeneity. Radiology. 2002;225:269–275. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkio J, Soinne L, Østergaard L, Helenius J, Kangasmaki A, Martinkauppi S, et al. Abnormal intravoxel cerebral blood flow heterogeneity in human ischemic stroke determined by dynamic susceptibility contrast magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 2005;36:44–49. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000150495.96471.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sette G, Baron JC, Mazoyer B, Levasseur M, Pappata S, Crouzel C.Local brain haemodynamics and oxygen metabolism in cerebrovascular disease. Positron emission tomography Brain 1989112Pt 4931–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GN. Researches on the circulation time in organs and on the influences which affect it. Parts I.-III. J Physiol. 1894;15:1–89. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1893.sp000462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndubuizu O, LaManna JC. Brain tissue oxygen concentration measurements. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1207–1219. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa RS, Baron JC.Perfusion Thresholds in Cerebral IschemiaIn: Donnan GA, Baron JC, Davis SM, Sharp FR (eds). Informa Healthcare USA, Inc.: New York; 200731–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlik G, Rackl A, Bing RJ. Quantitative capillary topography and blood flow in the cerebral cortex of cats: an in vivo microscopic study. Brain Res. 1981;208:35–58. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90619-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villringer A, Them A, Lindauer U, Einhaupl K, Dirnagl U. Capillary perfusion of the rat brain cortex. An in vivo confocal microscopy study. Circ Res. 1994;75:55–62. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinfeld D, Mitra PP, Helmchen F, Denk W. Fluctuations and stimulus-induced changes in blood flow observed in individual capillaries in layers 2 through 4 of rat neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15741–15746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J, Abounader R, Schrock H, Zeller K, Duelli R, Kuschinsky W. Parallel changes of blood flow and heterogeneity of capillary plasma perfusion in rat brains during hypocapnia. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H1441–H1445. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.4.H1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abounader R, Vogel J, Kuschinsky W. Patterns of capillary plasma perfusion in brains in conscious rats during normocapnia and hypercapnia. Circ Res. 1995;76:120–126. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krolo I, Hudetz AG. Hypoxemia alters erythrocyte perfusion pattern in the cerebral capillary network. Microvasc Res. 2000;59:72–79. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1999.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RJ, Perry S, Hames TK, Pickard JD. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound studies of cerebral autoregulation and subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rabbit. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:601–610. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.4.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosset DG, Straiton J, McDonald I, Cockburn M, Bullock R. Use of transcranial Doppler sonography to predict development of a delayed ischemic deficit after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:183–187. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.2.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaslid R, Huber P, Nornes H. Evaluation of cerebrovascular spasm with transcranial Doppler ultrasound. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:37–41. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.1.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel MF, Scharbrodt W, Wachter D, Stein M, Schmidinger A, Boker DK. Arteriovenous differences of oxygen and transcranial Doppler sonography in the management of aneurysmatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15:630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voldby B, Enevoldsen EM, Jensen FT. Regional CBF, intraventricular pressure, and cerebral metabolism in patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:48–58. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.1.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HG, Shin HK, Shin YW, Lee JH, Hong KW. Role of nitric oxide in the CBF autoregulation during acute stage after subarachnoid haemorrhage in rat pial artery. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2003;17:563–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassen NA. The luxury-perfusion syndrome and its possible relation to acute metabolic acidosis localised within the brain. Lancet. 1966;2:1113–1115. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)92199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voldby B, Enevoldsen EM, Jensen FT. Cerebrovascular reactivity in patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:59–67. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.1.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Meng CJ, Shen XM, Shu Z, Ma C, Zhu GQ, et al. Potential contribution of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha, aquaporin-4, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 to blood-brain barrier disruption and brain edema after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;48:273–280. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9769-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Khan SA, Luo W, Nanduri J, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 mediates increased expression of NADPH oxidase-2 in response to intermittent hypoxia. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2925–2933. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin HK, Lee JH, Kim KY, Kim CD, Lee WS, Rhim BY, et al. Impairment of autoregulatory vasodilation by NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent superoxide generation during acute stage of subarachnoid hemorrhage in rat pial artery. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:869–877. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200207000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Nitric oxide neurotoxicity. J Chem Neuroanat. 1996;10:179–190. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(96)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Davisson RL. Hypertension and cerebrovascular dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2008;7:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri M, Ai J, Lakovic K, Macdonald RL. Mechanisms of microthrombosis and microcirculatory constriction after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2013;115:185–192. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1192-5_35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich B, Muller F, Feiler S, Scholler K, Plesnila N. Experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage causes early and long-lasting microarterial constriction and microthrombosis: an in vivo microscopy study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:447–455. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers WJ, Grubb RL, Jr, Baker RP, Mintun MA, Raichle ME. Regional cerebral blood flow and metabolism in reversible ischemia due to vasospasm. Determination by positron emission tomography. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:539–546. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.4.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura S, Sayama I, Yasui N, Uemura K. Sequential changes in cerebral blood flow and metabolism in patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1992;114:12–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01401107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minhas PS, Menon DK, Smielewski P, Czosnyka M, Kirkpatrick PJ, Clark JC, et al. Positron emission tomographic cerebral perfusion disturbances and transcranial Doppler findings among patients with neurological deterioration after subarachnoid hemorrhage Neurosurgery 2003521017–1022.discussion 1022-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rawi PG, Zygun D, Tseng MY, Hutchinson PJ, Matta BF, Kirkpatrick PJ. Cerebral blood flow augmentation in patients with severe subarachnoid haemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;95:123–127. doi: 10.1007/3-211-32318-x_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:656–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinprecht A, Czech T, Asenbaum S, Podreka I, Schmidbauer M.Low cerebrovascular reserve capacity in long-term follow-up after subarachnoid hemorrhage Surg Neurol 200564116–120.discussion 121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]