Abstract

Objectives

Effective pain assessment and pain treatment are key goals in community nursing homes, but residents’ psychiatric disorders may interfere with attaining these goals. This study addressed whether: (a) pain assessment and treatment obtained by nursing home residents with psychiatric disorders differs from that obtained by residents without psychiatric disorders; (b) this difference is found consistently across the four types of psychiatric disorder most prevalent in nursing homes (dementia, depression, serious mental illness, substance use disorder); and (c) male gender, non-white race, and longer length of stay add to psychiatric disorder to elevate risk of potentially adverse pain ratings and pain treatments.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Participants

13,507 National Nursing Home Survey 2004 (NNHS 2004) residents.

Measures

Demographic, diagnostic, pain, and medication items from the NNHS 2004.

Results

Compared to residents without psychiatric disorders, those with psychiatric disorders were less likely to be rated as having pain in the last 7 days, and had lower and more “missing”/ “don't know” pain severity ratings. They also were less likely to obtain opioids, and more likely to be given only non-opioid pain medications, even after statistically adjusting for demographic factors, physical functioning, and pain severity. These effects generally held across all four types of psychiatric disorders most prevalent in nursing homes, and were compounded by male, non-white, and longer-stay status.

Conclusion

Psychiatric disorders besides dementia may impact pain assessment and treatment in nursing homes. Nursing home residents with psychiatric disorders, especially male, non-white, and longer-stay residents, should be targeted for improved pain care.

Keywords: Psychiatric disorder, pain, nursing homes

Objective

Effective pain assessment and pain treatment are key goals in community nursing homes (1). However, anecdotal clinical accounts (2-4) and studies of general health care in mixed-age patient populations (5-7) imply that psychiatric disorders may be a barrier to attaining these goals. Several studies indicate that dementia interferes with accurate assessment of nursing home residents’ pain (e.g., 8-12). However, with one exception (13), no one has considered whether the three other types of psychiatric disorder most prevalent in nursing homes [depression, serious mental illness, and substance use disorder (14-16)] also impact the quality of pain assessments obtained by nursing home residents.

Furthermore, little research has examined the implications of nursing home residents’ psychiatric disorders for the specific types of pain treatment they receive. Non-pharmacological pain management is rare in nursing homes, especially among cognitively impaired residents (17). Psychiatric disorders other than dementia may also impede efforts to provide nursing home residents with non-pharmacological pain interventions. Clinicians’ concerns about addiction risk, and adverse medication interactions, may cause them to avoid prescribing opioids to nursing home residents who have psychiatric disorders. However, no one has examined whether nursing home residents with psychiatric disorders are less likely to obtain opioids, and more likely to be provided only non-opioid medications, for their pain.

Previous research suggests that certain resident characteristics may compound the effects of psychiatric disorder on the pain assessments and treatments obtained by nursing home residents. Men are less likely to report pain than are women (18), thus, in nursing homes, being male may add to having a psychiatric disorder to predict lowered detection of pain and fewer pain treatments. Sengupta and colleagues (10) recently demonstrated that racial background, in combination with dementia, help to predict nursing home residents’ pain ratings: whereas 31% of white residents without dementia were rated by nursing home staff as having pain, this was true of only 12% of non-white nursing home residents with dementia. Longer length of stay may also elevate risk of unrecognized and undertreated pain, in part because longer-stay residents have more functional impairment that interferes with their ability to communicate pain, and obtain effective treatment for it, and also due to “clinical inertia,” care providers’ reduced responsiveness over time to patients’ pain symptoms (19). In this study we determine whether: (a) pain assessment and treatment obtained by nursing home residents with psychiatric disorders differs from that obtained by residents without psychiatric disorders; (b) this difference is found consistently across the four types of psychiatric disorder most prevalent in nursing homes (dementia, depression, serious mental illness, substance use disorder); and (c) male gender, non-white race, and longer length of stay add to psychiatric disorder to elevate risk of potentially adverse pain ratings and pain treatments.

Methods

Sample

Data for this study are from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey (NNHS 2004; 20). Sampling for NNHS 2004 comprised a two-stage probability design to include information from a nationally representative sample of U.S. nursing homes and nursing home residents. Final resident sample size was n=13,507 (mean age=81 years; SD=13); 71% women; 88% White; for further sampling and sample details, see 20).

Measures

Residents’ demographic, diagnostic, pain and medication information were obtained from the publically available NNHS 2004 Current Resident Questionnaire (CRQ; 21) and Long-term Care Medication Data (LCMD; 22) datasets. This information was collected by NNHS 2004 interviewers from nursing home staff familiar with sampled residents (23,24).

Demographic, functioning, and stay characteristics

These included age at interview, male gender (1=yes, 0=no), non-white race (1=yes, 0=no), physical functioning, a count of the number of activities of daily living residents could not engage in without staff assistance, and longer (1 year or more) length of stay (1=yes, 0=no).

Psychiatric disorder

Residents’ psychiatric disorders were identified by ICD-9-CM codes (25; Notes,Table 1) in CRQ diagnostic data fields. We used these codes to construct an overall dichotomous variable “presence of psychiatric disorder,” where “1” indicated presence of a dementia, depression, serious mental illness, substance use disorder diagnosis, or a combination of these psychiatric disorder diagnoses, and “0” indicated absence of any psychiatric disorder diagnosis. We also used the codes to create dichotomous variables indicating presence (1=yes, 0=no) of dementia diagnosis alone, depression diagnosis alone, serious mental illness diagnosis alone, and substance use disorder diagnosis alone, and dual diagnosis (2 or more of the aforementioned diagnoses).

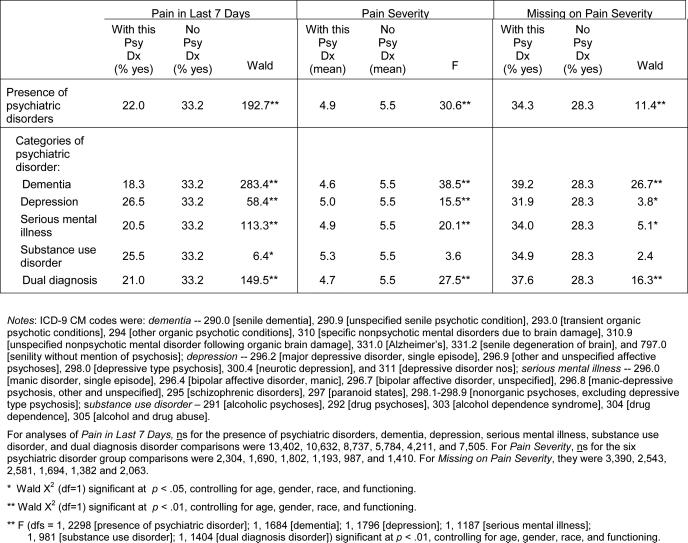

Table 1.

Pain Ratings Obtained by Residents With and Without Psychiatric Disorders

|

Pain ratings and pain treatment

These included pain in the last 7 days (1=yes, 0=no), pain severity (range=1 to 10), and “missing” or “don't know” (1=yes; 0=no) on pain severity ratings. About 98% of residents were assigned a definitive “yes” or “no” on the “pain in the last 7 days” item. Pain severity ratings, missingness on pain severity ratings, and pain treatments, were examined only for residents who rated “yes” on “pain in the last 7 days.”

Non-pharmacological pain treatment was assessed with a dichotomous (1=yes, 0=no) CRQ item indicating whether a resident had been provided “distraction, heat/cold massage, positioning, music therapy or other non-pharmacological pain treatment” in the last 7 days. Pharmacological pain treatment information was obtained from the LCM dataset (22), which includes comprehensive resident medication information for the 24 hours preceding the CRQ interview. National Drug Code therapeutic class codes (24) assigned to each medication were used to construct dichotomous variables (1=yes, 0=no) indicating whether, in the preceding 24 hours, a resident had taken opioid medication, only non-opioid analgesics (i.e., aspirin, acetaminophen, NSAIDs), or no pain medication.

Analytic Procedures

Using SPSS 18.0 statistical software, we first conducted cross-tabulations, logistic regression, and analyses of covariance, to determine group differences between residents with and without psychiatric disorder diagnoses on pain ratings and pain treatments. Analyses of group differences adjusted statistically for residents’ age, race, gender, physical functioning and, among residents rated as having pain, level of pain severity.

Next, we conducted three sets of logistic regressions with categorical variable contrasts to determine whether male gender, non-white race, and longer length of stay, respectively, combine with presence of psychiatric disorders, elevate the risk of obtaining potentially adverse pain ratings and pain treatments. The reference category in the categorical variable contrasts was the one hypothesized, based on previous research findings, to be most “disadvantaged” with regard to pain ratings and pain treatments (e.g., men with psychiatric disorders). Thus, odds ratios for each group contrasted with the reference group indicated group members’ increased odds of obtaining pain ratings and pain treatments in the “advantaged” direction, relative to the reference group. All of these categorical variable contrasts controlled statistically for residents’ chronological age, race (omitted if a variable in the model), gender (omitted if a variable in the model), physical functioning and, among residents rated as having pain, level of pain severity.

Results

Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders

In the overall 2004 NNHS sample, 30% of residents had no psychiatric disorder diagnosis (n=4033), 44% had only one psychiatric disorder diagnosis (n=5,931), and 26% (n=3,543) had a dual diagnosis, that is, two or more psychiatric disorder diagnoses. Among residents with only one psychiatric disorder diagnosis, 59% were assigned a diagnosis of dementia, 31% a depression diagnosis, 8% a serious mental illness diagnosis, and 2% a substance use disorder diagnosis. Among residents with dual diagnoses, the most common diagnostic combination was dementia with depression (59%), followed by depression with serious mental illness (21%), dementia with serious mental illness (15%), then substance use disorder in combination with other disorders (about 5%).

Psychiatric Disorders and Pain Ratings

Residents with psychiatric disorders were less likely than residents without psychiatric disorders to be rated as having pain in the last 7 days (Table 1; 22% versus 33%). Residents with dementia were especially unlikely to be rated as having pain (18%), followed by residents with serious mental illness (21%) and those with dual psychiatric diagnoses (21%). Statistically significant differences between the groups with and without psychiatric disorders remained after adjusting for residents’ age, race, gender, and physical functioning.

Compared to residents in pain without psychiatric disorders, residents in pain with psychiatric disorders were rated as having less severe pain (i.e., 4.9 versus 5.5). Residents in pain with dual diagnoses, serious mental illness, and dementia were assigned lowest pain severity ratings, followed by residents with depressive disorders. Differences between groups with and without each of these individual psychiatric disorder diagnoses remained statistically significant after adjusting for residents’ age, race, gender, and physical functioning.

Residents in pain who had psychiatric disorders also were more likely than residents in pain without psychiatric disorders to be assigned “missing” or “don't know” pain severity ratings (34% versus 28%). This pattern held for most of the individual types of psychiatric disorder, but was most pronounced among residents with dementia (39%) and those with dual psychiatric diagnoses (38%). Statistically significant group differences between residents with and without psychiatric disorders remained after controlling for residents’ age, race, gender, and physical functioning.

Psychiatric Disorders and Pain Treatment

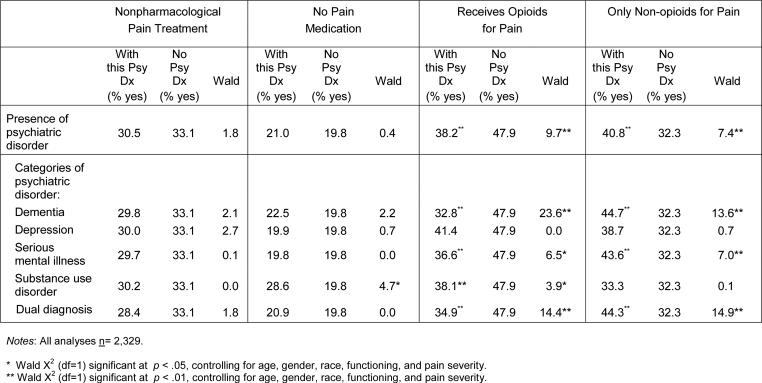

Group differences in non-pharmacological pain treatment were not statistically significant after controlling for age, race, gender, physical functioning, and pain severity (Table 2). However, whereas about 29% of residents in pain with substance use disorder diagnoses received no pain medication at all for their pain, this was the case for about 20% of residents in pain who did not have psychiatric disorders. This group difference was statistically significant after adjusting for the key covariates.

Table 2.

Pain Treatments Obtained by Residents With and Without Psychiatric Disorders

|

Residents in pain with psychiatric disorders were significantly less likely to receive opioids to treat their pain than were residents in pain without psychiatric disorders (38% versus 48%). Residents with dementia and dual diagnoses were least likely to receive opioids for their pain (33% and 35%, respectively), followed by those with serious mental illness (37%) and substance use disorders (38%). With the exception of depression, group differences between residents with and without each of the individual psychiatric disorders remained statistically significant after controlling for demographic factors, functioning, and pain severity.

Residents in pain with psychiatric disorders were more likely than residents in pain without psychiatric disorders to obtain only non-opioid medication (e.g., aspirin, acetaminophen, or NSAIDs), as treatment for their pain. Even after adjusting for key covariates, residents with dementia, serious mental illness, and dual diagnoses were significantly more likely to receive only non-opioids to treat their pain (about 45%, 44%, and 44%, respectively), in comparison to residents in pain who did not have psychiatric disorders (32%).

Gender, Race, and Length of Stay Added to Psychiatric Disorder

Group percentages and odds ratios indicating residents’ chances of obtaining pain rating and treatment outcomes are shown in Table 3; these odds ratios are statistically adjusted to control for residents’ age, gender, race, physical functioning, and pain severity.

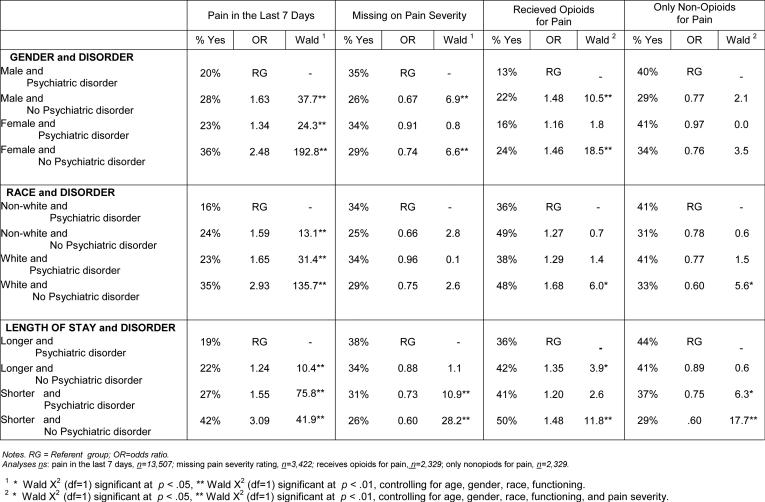

Table 3.

Pain Assessment and Treatment in Groups Combining Gender, Race, and Length of Stay with Psychiatric Disorder

|

Compared to men with psychiatric disorders, men without psychiatric disorders were about 60% more likely (OR=1.63), and women without psychiatric disorders more than twice as likely (OR=2.48), to be rated as having pain in the last 7 days. Similarly, men with psychiatric disorders were somewhat more likely to receive “missing” or “don't know” ratings for pain severity than were other sample members. With respect to pain treatment, men in pain with psychiatric disorders were about 50% less likely than men and women without psychiatric disorders to be provided opioid medication for pain relief.

With regard to racial background in combination with psychiatric disorder, white residents without psychiatric disorders were almost three times more likely (OR=2.93) than non-white residents with psychiatric disorders to be rated as having pain in the last 7 days. In addition, they were about 70% more likely than non-white residents in pain with psychiatric disorders to be provided opioids for relief of pain, and about 40% less likely to be given only non-opioid medications for pain.

Longer-stay residents with psychiatric disorders were three times less likely than shorter-stay residents without psychiatric disorders to be rated as having pain in the last 7 days, and 40% more likely to be given “missing” or “don't know” pain severity ratings. Being longer-stay and having a psychiatric disorder was associated with lowered chances of being provided nonpharmacological pain interventions (not shown; 34% of shorter stay residents without psychiatric disorder obtained nonpharmacological pain care, compared with 29% of longer stay residents with psychiatric disorders). Being longer-stay and having a psychiatric disorder also decreased the odds, by 50% to 65%, of obtaining opioid medication, and increased the odds, by 25% to 40%, of being provided only non-opioid medication for pain. In general, the compounding effects of male gender, non-white racial background, and longer length of stay, when combined with psychiatric disorder, held across the four individual psychiatric disorder diagnostic categories.

Conclusions

Recent studies document a high and growing prevalence of psychiatric disorder in long-term care settings (14-16). We also found a high prevalence of psychiatric disorder (70%) among NNHS 2004 residents, highlighting that the issue of psychiatric disorder as barrier to effective pain care is a very relevant health care issue for a substantial segment of the nursing home population.

Consistent with earlier anecdotal clinical accounts (2-4), and studies of health care in mixed-age patient populations (5-7), we found evidence that presence of psychiatric disorder is associated with the pain assessments obtained by nursing home residents. Specifically, NNHS 2004 residents who had psychiatric disorders were less likely to be noted as having pain, were rated as having less severe pain, and were more likely to have “missing”/”don't know” pain severity ratings, than were residents without psychiatric disorders. Notably, this effect was found for each of the four individual psychiatric disorders that are most prevalent in nursing homes -- depression, serious mental illness, and substance use disorder, as well as dementia -- and occurred independent of residents’ age, gender, racial background, and physical functioning.

Extending previous research (17), we also showed that some pain treatments obtained by residents with psychiatric disorders differed from those of residents who do not have psychiatric disorders. In particular, residents in pain with substance use disorder diagnoses were significantly more likely than comparison group members to receive no analgesics of any kind for their pain (30% versus 20%), even after adjusting for demographic characteristics, physical functioning and pain severity. Where substance use disorders are concerned, health care providers and residents themselves may hesitate to use substances for pain relief, out of fear of new or renewed substance use problems. However, the decision to dispense with analgesics when treating pain of residents with histories of substance misuse may result in continued, unnecessary suffering for these residents. Decision-making regarding pain treatments for long-term care residents with histories of substance misuse deserves further clinical and research attention.

In addition, residents with each of the four individual psychiatric disorders were less likely to be provided opioids, and more likely to be provided only non-opioid medications for pain. In general, these differences held independent of residents’ demographic characteristics, physical functioning, and pain severity. Again, these findings extend earlier research (8-12; 17) to demonstrate that dementia is not the only psychiatric condition that impacts pain care for nursing home residents. They suggest that nursing home care providers are cognizant of pain treatment recommendations that caution against use of opioid medication to treat older adults’ pain, particularly pain of older adults who also are prescribed psychoactive medications (1, 26). Further research should determine specific reasons that nursing home residents with psychiatric disorders have less access to opioids for pain than do residents without psychiatric disorders, and best practices to provide pharmacological regimens that combine analgesics and psychoactive medications in ways that safely and effectively balance risk of adverse medication outcomes against risk of uncontrolled pain for nursing home residents with psychiatric disorders.

Consistent with expectations based on previous research (10, 27-31), we found evidence that male gender, non-white racial background, and longer length of stay may compound the effects of having a psychiatric disorder on the pain assessments and pain treatments obtained by nursing home residents. These resident characteristics, when combined with presence of psychiatric disorder, often predicted reduced likelihood of being rated as having pain, and of obtaining opioids for pain, and increased likelihood of “missing”/”don't know” pain severity ratings, and of receiving only non-opioid analgesics for pain.

Further survey and direct observational research is needed to identify the specific resident characteristics associated with psychiatric problems, gender, race, and length of stay that account for these findings. For example, subsidiary data analyses revealed that the combined effects of psychiatric disorder and longer length of stay on residents’ pain care remained the same, even after we controlled statistically for presence of dementia. However, this finding does not rule out the possibility that communication difficulties interfere with pain care for longer-stay residents who also have psychiatric disorder. Other resident characteristics related to psychiatric disorder, gender, racial background, and length of stay (e.g., time of onset, duration, severity of the psychiatric disorder; communication deficits; pain stoicism; attitudes about use of substances to treat pain; recency of experiencing acute pain-inducing medical procedures) and characteristics of care providers (e.g., gender- and race-based stereotypes about pain tolerance and substance misuse; susceptibility to “clinical inertia” in pain care regimens) may help explain the findings we present here. These specific resident and care provider characteristics are important to identify because they are potentially malleable factors that can be foci for educational and clinical practice interventions to improve pain care for nursing home residents with psychiatric disorders.

This study has several limitations. The validity of NNHS 2004 psychiatric disorder diagnostic codes and pain measures has been questioned (e.g., 32, 33). No independent data source was available to us to verify the source, accuracy, and recency of the ICD-9 psychiatric diagnoses recorded in the NNHS 2004 survey. Moreover, certain facility characteristics, such as size, and use of MDS 2.0 pain items as care-quality indicators, may have introduced bias into the NNHS 2004 pain ratings (34). Also, NNHS 2004 data are cross-sectional, precluding inferences about causal connections between residents’ psychiatric disorders and their pain assessments and treatments. Longitudinal research comparing residents with and without psychiatric disorder on temporally- lagged, short-term relationships among pain, pain treatments, and pain treatment outcomes, is needed to provide stronger evidence about psychiatric disorder as barrier to high quality, effective pain care for nursing home residents. Finally, statistical significance does not necessarily denote clinical significance (35): although all of the statistically significant group differences we report here have correspondingly significant effect sizes, they are generally small. Thus, further research should address the clinical meaningfulness of findings like ours.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provides new information that indicates psychiatric disorders alone, and in combination with male gender, non-white racial background, and longer length of stay, may act as barriers to optimal pain assessment and pain treatments for nursing home residents. Next steps are to identify the specific reasons for this; then, based on that information, to implement educational and clinical practice interventions that result in improved pain care for long-term care residents who have psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants AA017477 and AA15685 and by Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Services research funds. We thank Bernice Moos for her help with data preparation and analysis. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Brennan is responsible for this study's concept and design, analyses and interpretation of the data, and preparation of the manuscript. Dr. SooHoo is responsible for analyses of the data and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1331–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley AS, Siegler EL, Reid MC. Pitfalls and recommendations regarding management of acute pain among hospitalized patients with dementia. Pain Med. 2008;9:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirsh KL. Differentiating and managing common psychiatric comorbidities seen in chronic pain patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2010;24:39–47. doi: 10.3109/15360280903583123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris DB. In: Sociocultural and religious meanings of pain, in Psychosocial Factors in pain: Critical Perspectives. Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, editors. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1999. pp. 118–131. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frayne SM, Halanych JH, Miller DR, et al. Disparities in diabetes care: Impact of mental illness. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2631–2638. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen L, Normand S, Druss B, et al. Process of care and outcome after acute myocardial infarction for patients with mental illness in the VA health care system: are there disparities? Health Serv Res. 2003;38:41–61. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1516–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Won A, Lapane K, Gambassi G, et al. Correlates and management of nonmalignant pain in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology. JAMA. 1998;279:1877–1882. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sengupta M, Bercovitz A, Harris-Kojetin LD. NCHS data brief. 30. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2010. Prevalence and management of pain, by race and dementia among nursing home residents: United States, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher SE, Burgio LD, Thorn BE, et al. Pain assessment and management in cognitively impaired nursing home residents: Association of certified nursing assistant pain report, minimum data set pain report, and analgesic medication use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:152–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds KS, Hanson LC, DeVellis RF, et al. Disparities in pain management between cognitively intact and cognitively impaired nursing home residents. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walid MS, Zaytseva NV. Pain in nursing home residents and correlation with neuropsychiatric disorders. Pain Physician. 2009;12:877–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagchi AD, Verdier JM, Simon SE. How many nursing home residents live with a mental illness? Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:958–964. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.7.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fullerton CA, McGuire TG, Feng Z, et al. Trends in mental health admissions to nursing homes, 1999-2005. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:965–971. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemke SP, Schaefer JA. Recent changes in the prevalence of psychiatric disorder among VA nursing home residents. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:356–363. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jablonski A, Ersek M. Nursing home staff adherence to evidence-based pain management practices. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35:28–37. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20090701-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribiero-Dasilva MC, et al. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10:447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Glickman M, et al. Developing a quality measure for clinical inertia in diabetes care. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1836–1853. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. [April 1, 2012];National Nursing Home Survey 2004 website. Available at hhtp://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nnhs/about_nnhs.htm.

- 21. [April 1, 2012];NNHS 2004 Current Resident Questionnaire. Available at: hhtp://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nnhs/nnhs_questionnaires.htm.

- 22. [April 1, 2012];NNHS 2004 Long-term Care Medication Data. Available at: hhtp://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nnhs/drug-database.

- 23.Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, et al. National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 Overview. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2009;13(167):1–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dwyer LL. Collecting medication data in the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2009;1(47):1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hart AC, Hopkins CA, editors. Ingenix. Eden Prairie, MN: 2003. International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision Clinical Modification Expert for Hospitals Volumes 1, 2, and 3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Arcy Y. Pain in the older adult. Nurse Pract. 2008;33:18–24. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000312997.00834.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burnett-Zeigler I, Zivin K, Ilgen M, et al. Depression treatment in older adult veterans. Am J Geriatr Psychiat. 2012;20:228–238. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ff6655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiminez DE, Bartels SJ, Cardenas V, et al. Cultural beliefs and mental health treatment preferences of ethnically diverse older adult consumers in primary care. Am J Geriatr Psychiat. 2012;20:533–542. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318227f876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker KA, et al. The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4:277–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim G, DeCosterm J, Chiraboga DA, et al. Associations between self-rated mental health and psychiatric disorder among older adults: Do racial/ethnic differences exist? Am J Geriatr Psychiat. 2011;19:416–422. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181f61ede. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szczerbenski K, Hirdes JP, Zyczkowska J. Good news and bad news: Depressive symptoms decline and undertreatment increases with age in home care and institutional settings. Am J Geriatr Psychiat. 2011;20:1045–1056. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182331702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fries BE, Simon SE, Morris JN, et al. Pain in U.S. nursing homes: validating a pain scale for the Minimum Data Set. Gerontologist. 2001;41:173–179. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cadogan MP, Schnelle JF, Yamamoto-Mitani N, et al. A minimum data set prevalence of pain quality indicator: Is it accurate and does it reflect differences in care processes? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:281–285. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutchinson AM, Milke DL, Maisey S, et al. The Resident Assessment Instrument-Minimum Data Set 2.0 quality indicators: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;166:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraemer HC, Morgan GA, Leech NL, et al. Measures of clinical significance. J Am child adolesc psychiatr. 2003;42:1524–1529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]