Abstract

Currently, two prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines targeting HPV 16 and 18 have been shown to be highly efficacious for preventing precursor lesions, although the effectiveness of these vaccines in real world clinical settings must still be determined. Toward this end, an ongoing statewide surveillance program was established in New Mexico to assess all aspects of cervical cancer preventive care. Given that the reduction in cervical cancer incidence is expected to take several decades to manifest, a systematic population-based measurement of HPV type-specific prevalence employing an age- and cytology-stratified sample of 47,617 women attending for cervical screening was conducted prior to widespread HPV vaccination. A well-validated PCR method for 37 HPV genotypes was used to test liquid-based cytology specimens. The prevalence for any of the 37 HPV types was 27.3% overall with a maximum of 52% at age 20 years followed by a rapid decline at older ages. The HPV 16 prevalence in women aged ≤ 20 years, 21-29 years, or ≥ 30 years was 9.6%, 6.5%, and 1.8%, respectively. The combined prevalence of HPV 16 and 18 in these age groups was 12.0%, 8.3% and 2.4%, respectively. HPV 16 and/or HPV 18 were detected in 54.5% of high-grade squamous intraepithelial (cytologic) lesions (HSIL) and in 25.0% of those with low-grade SIL (LSIL). These baseline data enable estimates of maximum HPV vaccine impact across time and provide critical reference measurements important to assessing clinical benefits and potential harms of HPV vaccination including increases in non-vaccine HPV types (i.e., type replacement).

Keywords: population-based HPV prevalence, HPV vaccine impact

Introduction

The discovery that persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection causes cervical cancer1 and that HPV is a necessary cause of cervical cancer everywhere in the world2 has revolutionized cervical cancer prevention in the 21st century. DNA tests for the detection of HPV3-8 and prophylactic vaccines against HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18 infections and related cervical disease9-11 have been developed and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and regulatory bodies throughout the world. Despite the role of the Pap test in reducing the cervical cancer burden in many western countries including the United States (U.S.)12, the landscape of cervical cancer prevention will increasingly shift toward utilizing these HPV-targeted technologies because they are more efficacious and, if used rationally in an age-appropriate manner13, are more cost-effective than Pap-based screening programs14-16. Already, national HPV vaccination programs have been established in Australia, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere17-18, and HPV-based screening has been introduced in the U.S.19 and is being considered in Europe20. In the future, new HPV vaccines that target HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 may become available13 (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00943722). Ultimately, cervical cancer prevention based on HPV vaccination in 11-12 year old girls and HPV testing in women 30 and older should replace Pap-based programs and could be the flagship for cancer prevention and cost-effective preventive programs globally21.

The implementation of any new technology requires surveillance to measure the population effectiveness. Randomized clinical trials are essential for establishing the efficacy of a new intervention but for logistic reasons are not capable of establishing overall efficacy in the general population in which an intervention will be implemented 22. Ultimately, surveillance in the general population is needed to assess the true clinical benefits and costs of implementing new technologies on the outcomes of interest.

To that end, a statewide registry, the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (NMHPVPR), was established in 2006 to monitor the impact of HPV vaccine introduction and changes in cervical cancer screening behaviors over time. It includes records of all Pap and HPV tests, and all cervical, vaginal and vulvar biopsies. As a first goal we wanted to describe the distribution of HPV genotypes in a large sample of the general New Mexico population of females participating in cervical screening prior to widespread HPV vaccination, thus providing a baseline for comparison with future vaccinated populations. Preventing cervical cancer is the primary goal of HPV vaccination but surrogate endpoints are required because reductions in cancer will take a decade or more to observe even in populations with high vaccine coverage23. Among the available surrogate endpoints, changes in HPV type-specific prevalence will be a more sensitive, objective and earlier indicator of HPV vaccine impact24 versus precancer endpoints which are subject to inter-observer variation25. . Our study enables estimations of HPV vaccine impact among women spanning a broad age range and with normal and abnormal cytology. In addition, these data provide a critical reference measurement important to assessing unanticipated outcomes such as increases in non-vaccine HPV types (i.e., HPV type replacement).

Materials and Methods

Registry

The New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (NMHPVPR) is located at the University of New Mexico and acts as a designee of the New Mexico Department of Health. The NMHPVPR operates under NMAC 7.4.3, which specifies the list of Notifiable Diseases and Conditions for the state of New Mexico. In 2006, with the intention of monitoring the impact of HPV vaccination, NMAC 7.4.3 specified that laboratories must report to the NMHPVPR all Pap cytology, cervical pathology, and HPV tests performed on New Mexico residents. NMAC 7.4.3 was updated in 2009 to include vulvar and vaginal pathology (nmhealth.org/erd/healthdata/pdf/Notifiable%20DC%20043009.pdf).

Study population and sample

During the 17-month period of December 2007 through April 2009 approximately 379,000 Pap tests were reported to the NMHPVPR by 9 in-state and 7 outof-state clinical laboratories. We collected all available liquid cytology Pap specimens from 7 of the 9 in-state laboratories, which accounted for 79% of all Pap tests done during this period. From each of these 7 labs we randomly selected specimens for HPV genotyping within four strata defined by the age of the woman (≤ 30 years vs. > 30 years) and by the cytologic result on the lab report (negative vs. abnormal). Target sampling proportions varied by strata: 45% of negative specimens in women ≤ 30 years, 8% of negative specimens in women > 30 years, and 100% of abnormal specimens, regardless of the woman’s age. Ultimately, a total of 59,644 specimens were retrieved and successfully genotyped for HPV. A schematic description of the sample design is provided in Supplemental Figure 1. Prior to HPV genotyping, specimens were de-identified by the use of randomly assigned study-specific identifiers. The UNM Human Research Review Committee approved this study.

HPV genotyping

The LINEAR ARRAY HPV Genotyping Test (HPV LA; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana USA) is a qualitative test for 37 HPV genotypes incorporating selective PCR amplification with biotinylated PGMY 09/11 L1 region consensus primers and colorimetric detection of amplified products bound to immobilized HPV genotype –related oligonucleotide probes on a LINEAR ARRAY HPV genotyping strip. PGMY-based HPV genotyping with the HPV LA and a prototype Line Blot assay, have been previously reported in detail27-29. Following vigorous mixing of the original liquid cytology specimens, 500 μL aliquots of SurePath™ (Beckton, Dickinson and Company, New Jersey USA) or ThinPrep® (Hologic, Inc., Massachusetts USA) were transferred to 12 mm x 75 mm polypropylene tubes and DNA was purified using a Cobas X421 robot (Roche Molecular Systems (RMS), Inc., California USA). The robot performed proteinase K digestion and inactivation with the final DNA eluate (150 μL) delivered into a 96-well QiaAmp plate (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Fifty microliters (50 μL) of purified DNA was transferred to a tube with 50 μL of HPV LINEAR ARRAY mastermix, and the mixture was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a Applied Biosystems Gold-plated 96-well GeneAmp PCR System 9700 as specified by the manufacturer. Controls for contamination and assay sensitivity were included in each 96-well assay.

Stability (storage temperature and time) and sensitivity studies were conducted prior to initiating the statewide sampling of Pap specimens (data not shown). Stability of beta-globin and HPV DNA was consistent with previous reports26. HPV genotyping results were equivalent for SurePath™ samples held at 4°C following clinical collection whether processed and subjected to HPV genotyping at 7 days or up to 45 days post clinical collection. Therefore, SurePath™ samples were stored at 4°C at clinical labs and at the study lab and subjected to aliquoting, purification and HPV genotyping between 30 and 45 days following clinical collection. HPV genotyping results were equivalent for ThinPrep® samples stored at room temperature and subjected to HPV genotyping between 45 days and 6 months following clinical collection.

Using the Roche HPV LA detection kit, hybridizations were automated using Tecan ProfiBlot-48 robots (Tecan, Austria). The Roche HPV LA Genotyping Test detects 13 high- and 24 low-risk HPV types. HPV 52 is not determined directly by a type-specific probe but rather by a probe that cross hybridizes with HPV 33, 35, 52, and 58. The presence of HPV 52 was inferred only if the cross-reactive probe was hybridized but there was no hybridization detected for the HPV 33, 35 and 58 type-specific probes. Notably, concurrent infections of type 52 with the 3 other types cannot be detected. Two independent readers interpreted the presence of HPV genotypes using a reference template provided by the manufacturer. Any discrepancies were identified by a custom computer application applied to the data input and were adjudicated by a third review.

HPV genotype groupings

In addition to HPV type-specific prevalence, the combined prevalence of various groupings of HPV types were also computed: 1) groups based on the risk for cervical cancer: carcinogenic (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) or low-risk (all other types including 6, 11, 26, 40, 42, 53, 54, 55, 61, 62, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70-73, 81-84, IS39, and 89); 2) the five most common HPV types that have been detected in cervical cancer worldwide (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45)30,31; 3) groups based on types targeted by HPV vaccines: bivalent Cervarix™ (HPV 16 and 18), quadrivalent Gardasil™ (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18), and the next generation nonavalent HPV vaccine (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58); 4) groups based on phylogenetic species32 group: alpha 1 (HPV 42), alpha 3 (HPV 61, 62, 72, 81, 83, 84, 89), alpha 5 (HPV 26, 51, 69, 82, IS39), alpha 6 (HPV 53, 56, 66), alpha 7 (HPV 18, 39, 45, 59, 68, 70), alpha 8 (HPV 40), alpha 9 (HPV 16, 31, 33, 35, 52, 58, 67), alpha 10 (HPV 6, 11, 55), alpha 11 (HPV 64, 73), alpha 13 (HPV 54), and alpha 15 (HPV 71).

Cytologic classifications

Cytologic results were classified according to the 2001 Bethesda System (TBS)33: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), atypical squamous cells cannot rule out HSIL (ASC-H), atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), and negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy. A small number of cytologic results were reported as LSIL cannot rule out HSIL (LSIL-H), a non-TBS categorization that has not been validated as a reproducible or clinically valuable cytologic category. We therefore grouped LSIL-H with ASC-H. Cytologic results reported as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 1 were classified as LSIL and results reported as CIN grade 2 (CIN2), CIN grade 3 (CIN3), carcinoma in situ (CIS), or possible carcinoma were classified as HSIL. Cytologic results of “atypical squamous and glandular cells of undetermined significance” were classified as AGUS. Cytology was based on local readings and no attempt was made to review them centrally or undertake quality assurance activities.

Statistical methods

The study sample was selected prior to performing a woman-level linkage of the Pap test database and, as a consequence, multiple Pap specimens were collected and genotyped for some women. Subsequently we performed a probabilistic linkage of all records in the NMHPVPR database using Link Plus (http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/tools/registryplus/lp_tech_info.htm), which allowed us to restrict the analysis to a single Pap specimen (the chronologically earliest) for women with more than one specimen in the study sample. This reduced the number of specimens in the analysis from 59,644 to 54,872. The linkage also gave us a Pap history for all women represented in the study sample extending back to at least January, 2006.

All analyses were performed using sample survey techniques appropriate for a stratified random sample with unequal sampling fractions. The sample fractions are provided in Supplemental Figure 1. Sample weights were computed as the inverse of the population sample fraction and variances were computed by the Taylor series linearization method. The SAS (v 9.2) procedure SURVEYFREQ was used to compute all proportions and SURVEYLOGIST was used to compute adjusted odds ratios. Smooth curves for the prevalence of HPV by age were computed using the LOESS procedure on the age-specific prevalence estimates from SURVEYFREQ. Confidence intervals were based on normal approximations.

Results

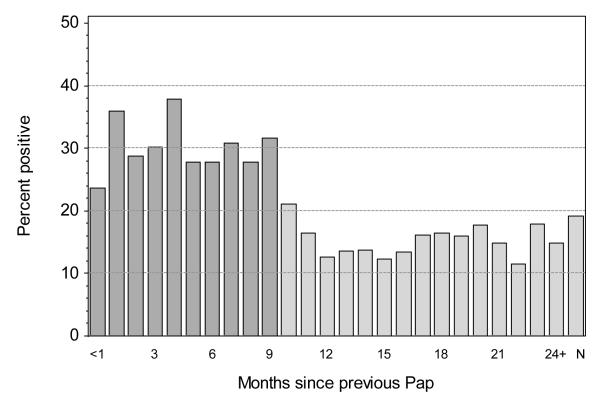

Figure 1 shows the overall prevalence of carcinogenic HPV types by the number of months between the genotyped Pap specimen and the preceding Pap test for the woman. Detection of HPV was less common in Pap specimens taken 10 months or more (≥ 300 days) after the preceding Pap test (14.2% carcinogenic and 25.9% overall) versus those taken less than 10 months (29.9% carcinogenic [p <0.0001] and 46.7% overall [p < 0.0001]). The prevalence of HPV was intermediate for specimens with no record of a preceding Pap test (19.2% carcinogenic and 32.6% overall). Based on these results we used a working definition for a screening Pap test as one with no preceding Pap test in the previous 299 days, including those with no record of any preceding Pap test. This definition assumes that anyone returning in less than 10 months after the last screen was doing so for reasons other than routine annual screening. All estimates of HPV prevalence reported here have been restricted to these 47,617 screening Pap tests.

Figure 1.

Percent of cervical Pap specimens that are positive for any carcinogenic HPV type by the number of months since the previous Pap test. Specimens from women with no previous Pap test in the Registry are indicated as N. Pap specimens taken less than 10 months (< 300 days) after the preceding Pap test (darker shading) are not classified as screens and were excluded from analyses.

The prevalence of each of the 13 carcinogenic or high-risk HPV types, individually and in various groupings, is shown in Table 1. The prevalence of any HPV was 27.3% (95%CI: 26.8%-27.8%) and any carcinogenic HPV was 15.3% (95%CI: 14.9%-15.7%). The prevalence of the 5 most common carcinogenic HPV genotypes were HPV 16 (3.5%), HPV 51 (2.3%), HPV 39 (2.1%), HPV 59 (2.1%), and HPV 52 (1.9%). The combined prevalence of the HPV 16 and HPV 18 was 4.5%, of the five most prevalent carcinogenic HPV types (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33 and 45) found in invasive cancer worldwide30 and in the US31 was 7.2%, and of the 7 carcinogenic types (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) in the proposed nonavalent vaccine was 9.5%, the latter accounting for 62% of all carcinogenic HPV types detected. Low-risk HPV types were detected in 19.5% of specimens and 12.0% of specimens contained only low-risk HPV types. The five most common low-risk types were HPV 62 (3.0%), HPV 53 (2.9%), HPV 54 (2.3%), HPV 66 (2.3%), and HPV 61 (2.1%). The prevalence of each low-risk HPV type by age is provided in Supplemental Table 1. The most prevalent phylogenetic species group detected in women aged < 30 years was the alpha-9 group (HPV 16, 31, 33, 35, 52, 58, 67) followed by alpha-3 (HPV 61, 62, 72, 81, 83, 84, 89). In contrast, for women aged ≥ 30 years the alpha-3 group was the most prevalent group detected followed by alpha-9. The prevalence of each phylogenetic species group by age is provided in Supplemental Table 2. Infection with multiple HPV types was common (data not shown). Among women who were positive for any type of HPV, multiple types were detected in 41.8% (95% CI: 40.8%-42.8%) and were more common in specimens with abnormal cytology (62.5%, 95% CI: 61.6%-63.5%) than in negative specimens (37.4%, 95% CI: 36.2%-38.6%).

Table 1.

The percent of cervical Pap specimens positive for carcinogenic HPV types by the age of the woman. Percents have been adjusted for the sampling fractions.

| < 21 (n=8,060) |

21-24 (n=8,997) |

25-29 (n=11,302) |

30-49 (n=12,077) |

50+ (n=7,181) |

all ages (n=47,617) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| HPV type | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) |

| 16 | 9.6 | (9.0, 10.3) | 8.2 | (7.6, 8.7) | 5.2 | (4.8, 5.6) | 2.2 | (1.9, 2.5) | 1.3 | (1.0, 1.6) | 3.5 | (3.3, 3.6) |

| 18 | 3.0 | (2.7, 3.4) | 3.0 | (2.6, 3.3) | 1.7 | (1.5, 2.0) | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.9) | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.8) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.3) |

| 31 | 4.1 | (3.7, 4.6) | 4.4 | (4.0, 4.8) | 2.8 | (2.5, 3.1) | 1.4 | (1.1, 1.6) | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.8) | 1.8 | (1.7, 1.9) |

| 33 | 1.3 | (1.1, 1.6) | 1.0 | (0.8, 1.2) | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.9) | 0.3 | (0.2, 0.4) | 0.2 | (0.1, 0.3) | 0.5 | (0.4, 0.5) |

| 35 | 1.8 | (1.5, 2.1) | 1.9 | (1.6, 2.2) | 1.2 | (1.0, 1.4) | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.9) | 0.4 | (0.2, 0.6) | 0.9 | (0.8, 1.0) |

| 39 | 6.4 | (5.9, 6.9) | 5.1 | (4.6, 5.5) | 3.0 | (2.7, 3.3) | 1.5 | (1.2, 1.7) | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 2.1 | (2.0, 2.2) |

| 45 | 2.4 | (2.1, 2.8) | 2.3 | (2.0, 2.6) | 1.5 | (1.2, 1.7) | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.9) | 0.6 | (0.4, 0.8) | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.2) |

| 51 | 7.9 | (7.3, 8.4) | 5.5 | (5.0, 5.9) | 3.0 | (2.7, 3.3) | 1.2 | (1.0, 1.4) | 0.9 | (0.7, 1.2) | 2.3 | (2.1, 2.4) |

| 52 | 4.5 | (4.0, 4.9) | 4.3 | (3.9, 4.8) | 3.0 | (2.6, 3.3) | 1.5 | (1.2, 1.7) | 0.7 | (0.5, 0.9) | 1.9 | (1.8, 2.1) |

| 56 | 3.4 | (3.0, 3.8) | 2.9 | (2.6, 3.2) | 1.7 | (1.5, 2.0) | 0.9 | (0.7, 1.0) | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.7) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.3) |

| 58 | 3.7 | (3.3, 4.1) | 3.0 | (2.7, 3.4) | 1.6 | (1.3, 1.8) | 0.7 | (0.5, 0.9) | 0.4 | (0.3, 0.6) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.3) |

| 59 | 6.3 | (5.8, 6.9) | 4.6 | (4.2, 5.0) | 2.9 | (2.6, 3.2) | 1.3 | (1.0, 1.5) | 0.9 | (0.7, 1.2) | 2.1 | (2.0, 2.2) |

| 68 | 1.6 | (1.3, 1.9) | 1.6 | (1.3, 1.9) | 1.0 | (0.9, 1.2) | 0.7 | (0.5, 0.8) | 0.5 | (0.3, 0.6) | 0.8 | (0.7, 0.9) |

| 16 or 18 | 12.0 | (11.3, 12.7) | 10.6 | (10.0, 11.2) | 6.6 | (6.2, 7.0) | 2.9 | (2.5, 3.2) | 1.8 | (1.5, 2.2) | 4.5 | (4.3, 4.7) |

| 16,18,31,33 or 45 | 17.5 | (16.6, 18.3) | 16.3 | (15.5, 17.0) | 10.7 | (10.1, 11.2) | 5.1 | (4.6, 5.5) | 3.1 | (2.6, 3.5) | 7.2 | (6.9, 7.5) |

| 16,18,31,33,45,52 or 58 | 22.4 | (21.5, 23.3) | 21.3 | (20.5, 22.2) | 14.2 | (13.6, 14.8) | 6.9 | (6.4, 7.4) | 4.1 | (3.5, 4.6) | 9.5 | (9.2, 9.8) |

| Carcinogenic exc. 16,181 | 30.3 | (29.3, 31.3) | 27.1 | (26.2, 28.1) | 17.7 | (17.0, 18.4) | 9.4 | (8.7, 10.0) | 5.4 | (4.8, 6.0) | 12.5 | (12.2, 12.9) |

| Any Carcinogenic type | 35.5 | (34.4, 36.5) | 32.5 | (31.5, 33.5) | 21.8 | (21.0, 22.5) | 11.5 | (10.8, 12.2) | 6.9 | (6.3, 7.6) | 15.3 | (14.9, 15.7) |

| Any low-risk type | 36.8 | (35.7, 37.9) | 32.4 | (31.4, 33.4) | 24.1 | (23.3, 24.9) | 16.5 | (15.7, 17.4) | 12.9 | (12.0, 13.8) | 19.5 | (19.0, 19.9) |

| Low-risk only2 | 15.4 | (14.5, 16.2) | 15.0 | (14.2, 15.8) | 13.8 | (13.2, 14.5) | 11.5 | (10.8, 12.3) | 10.2 | (9.4, 11.0) | 12.0 | (11.6, 12.5) |

| Any HPV type | 50.8 | (49.7, 52.0) | 47.5 | (46.4, 48.6) | 35.6 | (34.7, 36.5) | 23.1 | (22.1, 24.0) | 17.2 | (16.2, 18.2) | 27.3 | (26.8, 27.8) |

The specimen is positive for at least one carcinogenic type other than 16 or 18. The specimen may also be positive for 16 and/or 18.

The specimen is positive for at least one of the low-risk types and negative for all carcinogenic types.

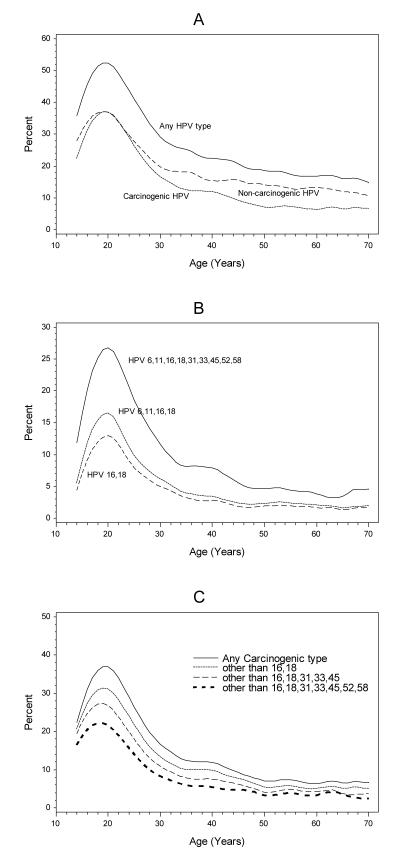

The overall prevalence of HPV rose sharply with increasing age in adolescent girls to a maximum of 52% at age 20 years and then rapidly declined after age 30 years, with a prevalence of 32% at age 30 and <20% by age 50 years (Figure 2a). Low risk types were relatively more common at older ages. Thus, while low-risk and carcinogenic types were equally common at age 20 years (37% for both), in women ≥30 years of age low-risk HPV types were much more commonly detected than carcinogenic HPV types (14.9% vs. 9.5%). Figure 2b shows the prevalence of carcinogenic HPV types included in the bivalent, quadrivalent and nonavalent vaccine by age. At age 20 years, the prevalence of HPV 16 and 18, the quadrivalent HPV vaccine types (HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18), and the nonavalent HPV vaccine types were 13%, 17%, and 27%, respectively. Figure 2c shows the reduction in prevalence of carcinogenic HPV as vaccine types are removed from the collection of carcinogenic types, modeling the impact of HPV vaccination now and in the future. This assumes 100% eradication of those types, which may be unachievable.

Figure 2.

The age-specific prevalence of HPV in cervical Pap specimens. (A) The percent of specimens positive for any HPV type, any carcinogenic HPV type, and any low-risk HPV type. (B) The percent positive for any bivalent HPV vaccine type (16 or 18), any quadrivalent HPV vaccine type (6, 11, 16 or 18), and any nonavalent HPV vaccine type (6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 or 58). (C) The percent positive for any carcinogenic HPV type, any carcinogenic type other than 16 or 18, any carcinogenic type other than 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, and any carcinogenic type other than 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 or 58. The specimen may be positive or negative for any of the excluded types.

As shown in Table 2 the prevalence of carcinogenic HPV increased with the severity of the cytologic result (excluding AGUS): Negative (12.5%), ASC-US (41.7%), LSIL (74.4%), and HSIL (90.9%). The prevalence of HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, and 58 increased while the prevalence of HPV 39, 45, 51, 56, 59, and 68 decreased. For low-risk types, the prevalence increased from negative (17.4%) to ASC-US (41.0%) to LSIL (69.9%), but then decreased in HSIL specimens (42.3%). This pattern held with few exceptions for all of the individual low-risk HPV types.

Table 2.

The percent of cervical Pap specimens positive for carcinogenic HPV types by cytologic result. Percents have been adjusted for the sampling fractions.

| Negative (n=33,614) |

ASC-US (n=8,746) |

LSIL (n=3,540) |

ASC-H (n=652) |

HSIL (n=517) |

AGUS (n=548) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| HPV type | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) |

| 16 | 2.6 | (2.4, 2.8) | 10.5 | (9.9, 11.2) | 19.3 | (18.0, 20.6) | 30.0 | (26.4, 33.5) | 46.8 | (42.5, 51.1) | 8.0 | (5.7, 10.3) |

| 18 | 0.9 | (0.8, 1.0) | 4.0 | (3.6, 4.4) | 6.8 | (6.0, 7.7) | 6.7 | (4.7, 8.6) | 10.2 | (7.6, 12.8) | 4.7 | (2.9, 6.5) |

| 31 | 1.4 | (1.3, 1.6) | 5.8 | (5.3, 6.3) | 8.9 | (7.9, 9.8) | 12.8 | (10.2, 15.4) | 12.5 | (9.6, 15.3) | 3.2 | (1.7, 4.7) |

| 33 | 0.4 | (0.3, 0.4) | 1.6 | (1.3, 1.8) | 2.9 | (2.3, 3.4) | 3.8 | (2.3, 5.3) | 4.7 | (2.9, 6.5) | 1.1 | (0.2, 2.0) |

| 35 | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.8) | 2.9 | (2.5, 3.2) | 5.6 | (4.9, 6.4) | 5.2 | (3.5, 6.9) | 7.0 | (4.8, 9.2) | 0.9 | (0.1, 1.7) |

| 39 | 1.7 | (1.5, 1.8) | 6.7 | (6.1, 7.2) | 12.7 | (11.6, 13.8) | 7.2 | (5.2, 9.2) | 7.0 | (4.8, 9.2) | 2.2 | (1.0, 3.5) |

| 45 | 0.9 | (0.8, 1.0) | 3.0 | (2.6, 3.3) | 5.1 | (4.3, 5.8) | 4.5 | (2.9, 6.1) | 2.9 | (1.4, 4.3) | 2.4 | (1.1, 3.6) |

| 51 | 1.7 | (1.5, 1.8) | 7.4 | (6.9, 8.0) | 18.7 | (17.4, 20.0) | 11.3 | (8.8, 13.7) | 13.9 | (10.9, 16.9) | 3.5 | (2.0, 5.1) |

| 52 | 1.6 | (1.5, 1.8) | 5.5 | (5.0, 5.9) | 7.3 | (6.5, 8.2) | 8.9 | (6.7, 11.1) | 6.3 | (4.2, 8.4) | 2.8 | (1.4, 4.2) |

| 56 | 0.9 | (0.8, 1.0) | 4.3 | (3.9, 4.7) | 13.1 | (12.0, 14.3) | 4.8 | (3.2, 6.5) | 4.7 | (2.9, 6.5) | 1.5 | (0.5, 2.6) |

| 58 | 0.9 | (0.8, 1.0) | 4.0 | (3.6, 4.4) | 7.6 | (6.7, 8.5) | 6.7 | (4.8, 8.7) | 10.3 | (7.7, 12.9) | 1.5 | (0.5, 2.5) |

| 59 | 1.8 | (1.6, 1.9) | 6.1 | (5.6, 6.6) | 9.6 | (8.6, 10.6) | 5.8 | (4.0, 7.6) | 5.5 | (3.5, 7.4) | 1.1 | (0.2, 2.0) |

| 68 | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.8) | 2.2 | (1.9, 2.5) | 3.9 | (3.2, 4.5) | 3.4 | (2.0, 4.9) | 1.0 | (0.1, 1.8) | 1.1 | (0.2, 2.0) |

| 16 or 18 | 3.4 | (3.2, 3.6) | 13.7 | (13.0, 14.4) | 25.0 | (23.6, 26.4) | 35.1 | (31.4, 38.7) | 54.5 | (50.2, 58.8) | 11.9 | (9.2, 14.7) |

| 16,18,31,33 or 45 | 5.7 | (5.4, 5.9) | 21.1 | (20.3, 22.0) | 36.8 | (35.2, 38.3) | 49.8 | (45.9, 53.6) | 67.5 | (63.5, 71.5) | 17.7 | (14.4, 20.9) |

| 16,18,31,33,45,52 or 58 | 7.6 | (7.3, 7.9) | 27.7 | (26.8, 28.7) | 45.6 | (43.9, 47.2) | 58.5 | (54.7, 62.3) | 75.4 | (71.7, 79.1) | 20.8 | (17.4, 24.2) |

| Carcinogenic exc. 16,181 | 10.2 | (9.9, 10.6) | 35.2 | (34.3, 36.2) | 64.6 | (63.0, 66.2) | 51.2 | (47.4, 55.0) | 56.8 | (52.5, 61.1) | 17.5 | (14.3, 20.7) |

| Any Carcinogenic type | 12.5 | (12.1, 12.9) | 41.7 | (40.7, 42.7) | 74.4 | (73.0, 75.8) | 70.4 | (66.9, 73.8) | 90.9 | (88.5, 93.4) | 26.3 | (22.6, 30.0) |

| Any low-risk type | 17.4 | (16.9, 17.9) | 41.0 | (40.0, 42.0) | 69.9 | (68.3, 71.4) | 41.8 | (38.0, 45.6) | 42.3 | (38.0, 46.6) | 19.4 | (16.0, 22.7) |

| Low-risk only2 | 11.7 | (11.3, 12.2) | 16.2 | (15.5, 17.0) | 20.2 | (18.9, 21.5) | 7.9 | (5.8, 10.0) | 4.6 | (2.8, 6.4) | 10.2 | (7.7, 12.7) |

| Any HPV type | 24.3 | (23.7, 24.8) | 57.9 | (56.9, 58.9) | 94.6 | (93.8, 95.3) | 78.3 | (75.1, 81.4) | 95.5 | (93.8, 97.3) | 36.5 | (32.4, 40.5) |

The specimen is positive for at least one carcinogenic type other than 16 or 18. The specimen may also be positive for 16 and/or 18.

The specimen is positive for at least one of the low-risk types and negative for all carcinogenic types.

The prevalence of each low-risk type and each phylogenetic group by cytologic result are provided in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The alpha 3 group was the most prevalent group detected in women with negative cytology results (9.9%). For all abnormal cytology groups, the alpha-9 group was the most prevalent group and the prevalence of this group increased from AGUS (16.4%) to ASC-US (27.3%) to LSIL (45.5%) to ASC-H (58.0%) to HSIL (73.8%). Notably, the alpha-7 group was the second most prevalent group detected in women with an AGUS test result (12.3%).

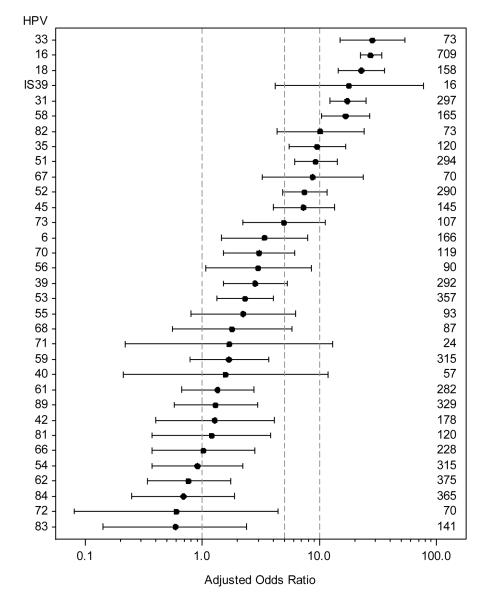

The age-adjusted odds ratios for high-grade disease (HSIL, ASC-H, or AGUS) vs. cytologic negative in specimens with a single type of HPV relative to HPV negative specimens are shown in Figure 3. Carcinogenic HPV types 33, 16, 18, 31, and 58 had odds ratios > 10.0, HPV 35, 51, 52 and 45 had odds ratios between 5.0 and 10.0, and HPV 39, 56, 59, and 68 had odds ratios < 5.0. The only low-risk HPV types with odds ratios > 5 were HPV 82, IS39, and 67. Supplemental Figure 2 presents the same odds-ratios without restriction to single HPV infections. Although the range of the odds-ratios is decreased, the ranking of the HPV types is very similar.

Figure 3.

Age-adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for cytologic result of High Grade (HSIL, ASC-H, or AGUS) vs. Negative in specimens with HPV of specified type (single infection) compared to those without HPV infection. Numbers on right margin are the total number of single HPV infections of the specified type. No high grade results found in specimens with HPV types 69 (n=3), 64 (n=5), 26 (n=3), or 11 (n=2). Reference lines for odds ratios of 1, 5, and 10 are added for readability.

Discussion

As part of our statewide New Mexico HPV prevention program, we measured the prevalence of 37 individual HPV types prior to widespread HPV vaccination. To our knowledge this is the largest systematic population-based HPV prevalence study conducted to date. The effort was conducted specifically for the purpose of measuring HPV vaccine impact and integrating HPV vaccination and cervical screening programs. The HPV prevalence estimates reported here are intended for use as a baseline for comparison to future samplings of the population. The large sample size enables precise estimates of both increases and decreases in HPV type-specific prevalence and, through linkage to cervical pathology results in the NMHPVPR, detection of changes in the incidence of HPV type-specific disease outcomes including CIN2 and CIN3.

Women aged ≤ 30 years of age represent the most relevant group for detecting an early impact of HPV vaccination on the prevalence of HPV. The stratified random sampling strategy employed in this study allowed us to increase the precision of HPV prevalence estimates in this younger age group as well as in women with abnormal cytology. HPV prevalence within abnormal cytology categories is important for understanding the degree that co-infections with non-vaccine and vaccine HPV types will modify the clinical impact of HPV vaccines. Furthermore, both abnormal and normal cytology categories will be essential to monitor HPV prevalence in the whole population since multiple types and changes in the reading of cytology may impact on the prevalence in each group separately and therefore mask any potential HPV type replacement.

In assessing the impact of different types on HSIL, we have provided two analyses, one restricted to single infections (Figure 3) and one including co-infections (Supplemental Figure 2), as it is impossible to determine which type was associated with the lesion when multiple types are present. Including co-infections would lead to a dilution of the true effects due to mis-attribution. As there is no strong evidence for preference of co-infection with specific pairs of types, this is unlikely to lead to a serious bias, but further detailed analyses of co-infections is currently ongoing and will be reported separately. These analyses of co-infections will be required to carefully address any potential suggestion of type replacement.

Among carcinogenic HPV types, the most commonly detected types in the population were HPV 16 followed by HPV types 51, 39 and 59. HPV types 39 and 59 have been reported previously as prevalent HPV types detected in invasive cervical cancers from Central and South America34. In line with this observation, the Hispanic and Native American ancestry of New Mexico’s populations may represent historical founder effects that would be expected to influence the HPV type distribution observed in our population sample. Consistent with the previously reported increased association of the alpha-7 group with adenocarcinoma30,35,36 (vs. squamous cell carcinoma), this group was the second most prevalent group detected in women diagnosed with AGUS.

Both carcinogenic and low-risk HPV had peak prevalence around age 20 followed by a rapid decline. Low-risk HPV declined less rapidly with age than carcinogenic HPV so that, while carcinogenic and low-risk HPV were equally common in younger ages, by age 30 low-risk HPV, especially types of the alpha-3 phylogenetic group, was detected more frequently than carcinogenic HPV. Little attention has been devoted to studying differences of type distribution at different ages. Similar to another US study that included large numbers of older women37, we failed to observe any notable upturn in HPV prevalence at older ages. .

Our data were consistent with the previously reported approximate 3-fold excess risk of CIN2+ associated with HPV 16 compared to all other carcinogenic HPV types38. Potentially of importance is the observation that HPV 33 has the highest age-adjusted odds ratio for HSIL when examining women with single infections. Notably when considering samples with co-infections, HPV 33 had the second highest age-adjusted odds ratio for HSIL, only surpassed by HPV-16. HPV 33 incident infections are at high risk of progression to CIN2/339-40 and among HPV 33-positive women the risk of carcinoma in situ, adenocarcinoma in situ or invasive cervical cancer relative to HPV 16 has been previously reported to be essentially equal to that of HPV 16-positive women31. It has also been suggested that HPV-33 may have a competitive advantage over several other oncogenic HPV types41 and it may be important to evaluate this following HPV 16/18 vaccination.

A considerably smaller US study of 4,150 females age 14-59 years derived from consecutive National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES; 2003 - 2006) was reported as a means for estimating HPV vaccine impact42,43. The NHANES study employed the same LA HPV genotyping assay used in our study. The most common HPV type detected in the NHANES study was not HPV 16 but rather low-risk HPV 62 (6.5%). The next most prevalent HPV types were HPV 53 (5.8%), and HPV 84 (4.8%). Overall HPV prevalence for the same 37 HPV types was considerably higher in the NHANES study (42.5%, 95% CI: 40.3%–44.7%) compared to our study (27.3%, 95% CI: 26.8%-27.8%) with the greatest difference observed in the older age groups. The NHANES study used a cervicovaginal self-sampling method, which may have resulted in increased prevalence, consistent with the lower specificity of self-collection compared to clinician collection with HPV DNA testing, and probably led to an oversampling of vaginal HPV types including HPV 62 and 8444,45.

Perhaps also because of cervicovaginal sampling the NHANES-based study reported a higher prevalence for HPV types 6 and 11 in girls 14-19 versus those 20-24 years of age or older. In contrast, the highest prevalence of HPV 16 and 18 and for low-risk and carcinogenic HPV type groupings was seen in those 20-24 years of age.

Another study conducted to estimate the potential impact of HPV vaccines was reported from Denmark46. Both our New Mexico and the Danish study analyzed samples from women participating in cervical screening. The Danish study excluded follow-up Pap tests after an abnormal cervical cytology/histology diagnosis within 12 months of the index sample. It is important to note that different age strata were reported for the NHANES, New Mexico and Danish studies and the two youngest age categories overlapped the peak of HPV prevalence at around age 20. This could at least partially explain differences in results although inherent differences in the underlying type-specific HPV prevalence, as well as age-related sexual behaviors of the populations may be contributing factors. For example in the NHANES study, approximately 16% of individuals reported never having sexual intercourse, which would be expected to be less common in those participating in cervical screening.

One of the limitations of our study is that women would have to be undergoing screening to be included but this will be the case in future samplings where we will target the same laboratories and compare age distributions within and between laboratories for the two sampling periods. Unscreened women would presumably have higher prevalence of CIN2/3 so any sampling strategy targeting women who are screening will likely underestimate the prevalence of carcinogenic HPV genotypes.

Population-based HPV prevalence estimates represent both persistent and incident HPV infections and will be expected to differ for a variety of reasons including: the sampling strategy, the overall exposure risk profile of the population being sampled including the proportion of individuals who are not yet sexually active, the cervical sampling methods and devices, and the sensitivity and specificity of the HPV detection assays. Differences will also be expected when assessing routine cervical screening tests versus samples which include repeat referral Pap tests wherein the later would be expected to yield higher HPV prevalence estimates. To address this, we assessed cervical screening histories using the NMHPVPR surveillance data through woman-level linkages. The resulting sample used for estimating HPV prevalence excluded specimens from women who had any record in the Registry of a Pap test within the previous 10 months. In support of using this latter selection criterion, we provide evidence of significantly greater HPV prevalence among Pap tests collected at intervals of less than 10 months since a woman’s preceding Pap test. We highlight our working definition of a screening (vs. a diagnostic) Pap test given the inherent challenges expected when conducting longitudinal evaluations and related HPV prevalence comparisons in the context of cervical screening. Evolving data applicable to US and other populations support lengthening of cervical screening intervals and starting screening at an older age (e.g. age 25 or 30 years), which may itself result in a corresponding reduction in the detection of at least some proportion of transient HPV infections and their associated abnormalities, which are known to be most common in younger women. We acknowledge that careful consideration of sampling strategies will be critical when proposing cross-sectional approaches to estimate HPV genotype prevalence as an indicator of HPV vaccine impact.

With these caveats in mind, reductions in the prevalence of certain HPV genotypes resulting from HPV vaccination will be expected to precede or be coincident with reductions in clinically relevant measures such as abnormal cervical cytology and histology. Comparisons of results from various populations would benefit from standardization of HPV prevalence estimates. Standardization procedures should consider establishing a specific overall age range (e.g. 20 to 59 years) and include adjustments for the population age distribution, HPV types included in the prevalence measures, and HPV assay sensitivity referenced to Hybrid Capture 2 HPV Test (Qiagen, Silver Spring, MD, USA) or to international HPV standards47. Specific proposals for reporting HPV prevalence are being developed and will be reported separately.

The impact of HPV vaccines on cervical cancer incidence will be dependent on vaccine related issues such as age of vaccination in relation to the age of sexual debut for the population, vaccine coverage, efficacy achieved with one, two and three doses of vaccine, the level of cross-protection afforded against HPV types not included in the vaccine preparations, durability of vaccine efficacy as well as population characteristics including the baseline prevalence of HPV types for which HPV vaccination provides protection versus the prevalence of other HPV types that will not be prevented by current formulations, and future screening efficacy and coverage. Given these complexities it will be difficult to directly translate measurable changes in HPV prevalence to expected reductions in clinically meaningful endpoints including abnormal cytology and CIN. Models have been proposed23, but they all rely on assumptions that have not been verified. Yet, HPV is the necessary cause of cervical cancer so the reduction in HPV prevalence must therefore correlate with cancer protection.

Data from phase III clinical trials where over 90% of participants received 3 doses of HPV vaccine-9-11, 48 provide us with the best current estimates of potential vaccine impact using approximated naïve populations as well as more general populations that included sexually active women with prior or current HPV infections. In the combined FUTURE I and II population that was naïve to 14 HPV types at baseline47, the vaccine impact on Pap test abnormalities irrespective of causal HPV type at the end of the study (average follow-up 3.6 years) resulted in an overall reduction of 17.1% for any abnormality and there was a general increase in reduction with increasing lesion severity: LSIL, 17.0% reduction, 95% CI (8.8% to 24.4%); HSIL, 44.5% reduction, 95% CI (4.3% to 68.6%).

In 2006 the quadrivalent HPV vaccine was licensed in the US. Although New Mexico focused its initial vaccine implementation efforts on girls ages 11-14, we acknowledge that at least some proportion of the women who underwent Pap testing had been vaccinated. We are currently working to describe HPV vaccine implementation in New Mexico using statewide HPV vaccine administrative data. Exclusions of vaccinated women from HPV prevalence estimates can therefore be reconsidered in subsequent analyses. Through comprehensive HPV genotyping studies such as that reported here, through similar HPV genotyping studies in population-based CIN and through linkages between the NMHPVPR and HPV vaccine administrative data, we will be able to contribute to more precisely understanding longitudinal changes in HPV prevalence and HPV-related disease incidence in New Mexico’s populations in the vaccine era. Overall, these efforts will be important to establishing the rational integration of HPV vaccination and cervical screening as complementary cervical cancer prevention strategies and will serve to inform public health practices and policy.

Supplementary Material

Novelty & Impact Statement.

The New Mexico HPV Pap Registry is a public health resource established to monitor the impact of HPV vaccination and changes in cervical screening practices and outcomes. As a complement to these efforts informing the integration of primary and secondary cervical cancer prevention, we report the distribution of HPV genotypes in a large sample of the New Mexico population prior to widespread vaccination. These data represent an essential baseline for comparison to future vaccinated populations.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the directors and staff of the New Mexico laboratories contributing specimens to this investigation and to Ray Apple PhD who has continuously extended efforts to enable the laboratory capacity required to perform a statewide effort of this magnitude. Special thanks to our students, Caitlin Hillygus, Christopher Romero and Anthony Pena working on this project and to the members of the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry (NMHPVPR) Steering Committee who supported the concept and directions of the NMHPVPR through their generous efforts over many years. Current members of the NMHPVPR Steering Committee are as follows: Nancy E. Joste, MD, Walter Kinney, MD, Cosette M. Wheeler, PhD., William C. Hunt, MS, Deborah Thompson, MD MSPH, Susan Baum, MD MPH, Linda Gorgos, MD MSc, Alan Waxman, MD MPH, David Espey MD, Jane McGrath MD, Steven Jenison, MD, Mark Schiffman, MD MPH, Philip Castle, PhD MPH, Vicki Benard, PhD, Debbie Saslow, PhD, Jane J.. Kim PhD, Mark H. Stoler MD, Jack Cuzick, PhD.

Abbreviations

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- HSIL

high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions

- LSIL

low-grade grade squamous intraepithelial lesions

- US

United States

- NMHPVPR

New Mexico HPV Pap Registry

- HPV LA

HPV LINEAR ARRAY

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- TBS

the 2001 Bethesda System

- ASC-H

atypical squamous cells cannot rule out HSIL

- AGUS

atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance

- ASC-US

atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

- LSIL-H

LSIL cannot rule out HSIL

- CIN

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- CIN1

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1

- CIN2

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2

- CIN3

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3

- CIS

carcinoma in situ

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement CMW has received funds through the University of New Mexico from GlaxoSmith Kline and Merck and Co.,Inc. for HPV vaccine studies and equipment and reagents for HPV genotyping from Roche Molecular Systems. PEC has received HPV tests and testing for research at a reduced or no cost from Roche and Qiagen, has a non-disclosure agreement with Roche and serves on a Merck Data Safety and monitoring board.

Reference List

- (1).Durst M, Gissmann L, Ikenberg H, zur HH. A papillomavirus DNA from a cervical carcinoma and its prevalence in cancer biopsy samples from different geographic regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:3812–3815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.12.3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, Walter SD, Hanley J, Ferenczy A, Ratnam S, Coutlée F, Franco EL, Canadian Cervical Cancer Screening Trial Study Group Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579–1588. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Naucler P, Ryd W, Tornberg S, Strand A, Wadell G, Elfgren K, Rådberg T, Strander B, Forslund O, Hansson BG, Hagmar B, Johansson B, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589–1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bulkmans NW, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, van Kemenade FJ, Boeke AJ, Bulk S, Voorhorst FJ, Verheijen RH, van Groningen K, Boon ME, Ruitinga W, van Ballegooijen M, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, Confortini M, Dalla Palma P, Del Mistro A, Ghiringhello B, Girlando S, Gillio-Tos A, De Marco L, Naldoni C, Pierotti P, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Anttila A, Kotaniemi-Talonen L, Leinonen M, Hakama M, Laurila P, Tarkkanen J, Malila N, Nieminen P. Rate of cervical cancer, severe intraepithelial neoplasia, and adenocarcinoma in situ in primary HPV DNA screening with cytology triage: randomised study within organised screening programme. BMJ. 2010;340:c1804. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1804. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1804.:c1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry K-U, Meijer CJLM, Hoyer H, Ratname S, Szarewski A, Birembaut P, Kulasingam S, Sasieni P, Iftner T. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int. J. Cancer: 2006;119:1095–1101. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).FUTURE II Study Group Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915–1927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, Perez G, Harper DM, Leodolter S, Tang GW, Ferris DG, Steben M, Bryan J, Taddeo FJ, Railkar R, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1928–1943. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, Castellsague X, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, Hedrick J, Jaisamrarn U, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet. 2009;374:301–314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Cervix Cancer Screening. IARC Press. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention; 2005. [10] Ref Type: Serial (Book,Monograph) [Google Scholar]

- (13).Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370:890–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Stout NK, Salomon JA, Kuntz KM, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus DNA testing and HPV-16,18 vaccination. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:308–320. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kim JJ, Goldie SJ. Health and economic implications of HPV vaccination in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:821–832. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kim JJ, Ortendahl J, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical cancer screening in women older than 30 years in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:538–545. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-8-200910200-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Donovan B, Franklin N, Guy R, Grulich AE, Regan DG, Ali H, Wand H, Fairley CK. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination and trends in genital warts in Australia: analysis of national sentinel surveillance data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wong CA, Saraiya M, Hariri S, Eckert L, Howlett RI, Markowitz LE, Brotherton JM, Sinka K, Martinez-Montañez OG, Kjaer SK, Dunne EF. Approaches to monitoring biological outcomes for HPV vaccination: Challenges of early adopter countries. Vaccine. 2011 Jan 29;29(5):878–85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras N, Lorey T, Shaber R, Kinney W. Five-year experience of human papillomavirus DNA and papanicolaou test cotesting. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:595–600. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181996ffa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lynge E, Antilla A, Arbyn M, Segnan N, Ronco G. What’s next? Perspectives and future needs of cervical screening in Europe in the era of molecular testing and vaccination. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2714–2721. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Schiffman M, Castle PE. The Promise of Global Cervical-Cancer Prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2101–2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wacholder S. The impact of a prevention effort on the community. Epidemiology. 2005;16:1–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000147633.09891.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Cuzick J, Castañón A, Sasieni P. Predicted impact of vaccination against human papillomavirus 16/18 on cancer incidence and cervical abnormalities in women aged 20-29 in the UK. Br J Cancer. 2010 Mar 2;102(5):933–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605528. Epub 2010 Jan 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Chang Y, Brewer NT, Rinas AC, Schmitt K, Smith JS. Evaluating the impact of human papillomavirus vaccines. Vaccine. 2009 Jul 9;27(32):4355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Carreon JD, Sherman ME, Guillén D, Solomon D, Herrero R, Jerónimo J, Wacholder S, Rodríguez AC, Morales J, Hutchinson M, Burk RD, Schiffman M. CIN2 is a much less reproducible and less valid diagnosis than CIN3: results from a histological review of population-based cervical samples. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2007;26:441–6. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0b013e31805152ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Castle PE, Solomon D, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Concepcion Bratti M, Sherman ME, Cecilia Rodriguez A, Alfaro M, Hutchinson ML, Terence Dunn S, Kuypers J, Schiffman M. Stability of archived liquid-based cervical cytologic specimens. Cancer. 2003 Apr 25;99(2):89–96. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Alessi TQ, Wheeler CM, Coutlée F, Hildesheim A, Schiffman MH, Scott DR, Apple RJ. Improved amplification of genital human papillomaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:357–361. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.357-361.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Peyton CL, Gravitt PE, Hunt WC, Hundley RS, Zhao M, Apple RJ, Wheeler CM. Determinants of genital human papillomavirus detection in a US population. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1554–1564. doi: 10.1086/320696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gravitt PE, Schiffman M, Solomon D, Wheeler CM, Castle PE. A comparison of linear array and hybrid capture 2 for detection of carcinogenic human papillomavirus and cervical precancer in ASCUS-LSIL triage study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1248–1254. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).de Sanjosé S, Quint WGV, Alemany L, Geraets DT, Klaustermeier JE, Lloveras B, Tous S, Felix A, Bravo LE, Shin HR, Vallejos CS, de Ruiz PA, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional survey. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1048–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Wheeler CM, Hunt WC, Joste NE, Key CR, Quint WGV, Castle PE. Human papillomavirus genotype distributions: implications for vaccination and cancer screening in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:475–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Bernard HU, Burk RD, Chen Z, van DK, Hausen H, de Villiers EM. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology. 2010;401:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O’Connor D, Prey M, Raab S, Sherman M, Wilbur D, Wright T, Jr, Young N, Forum Group Members. Bethesda 2001 Workshop The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114–2119. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Bosch FX, Manos MM, Muñoz N, Sherman M, Jansen AM, Peto J, Schiffman MH, Moreno V, Kurman R, Shah KV. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a worldwide perspective. International biological study on cervical cancer (IBSCC) Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(11):796–802. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.11.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Clifford G, Franceschi S. Members of the human papillomavirus type 18 family (alpha-7 group) share a common association with adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1684–85. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Schiffman M, Clifford G, Buonaguro FM. Classification of weakly carcinogenic human papillomavirus types: addressing the limits of epidemiology at the borderline. Infect Agent Cancer. 2009;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras N, Lorey T, Shaber R, Kinney W. Five-year experience of human papillomavirus DNA and Papanicolaou test cotesting. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Mar;113(3):595–600. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181996ffa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Castle PE, Solomon D, Schiffman M, Wheeler CM. Human papillomavirus type 16 infections and 2-year absolute risk of cervical precancer in women with equivocal or mild cytologic abnormalities. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Jul 20;97(14):1066–71. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Insinga RP, Perez G, Wheeler CM, Koutsky LA, Garland SM, Leodolter S, Joura EA, Ferris DG, Steben M, Hernandez-Avila M, Brown DR, Elbasha E, et al. FUTURE I Investigators Incident cervical HPV infections in young women: transition probabilities for CIN and infection clearance. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:287–96. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Bulkmans NW, Bleeker MCG, Berkhof J, Voorhorst FJ, Snijders PJF, Meijer CJLM. Prevalence of types 16 and 33 is increased in high-risk human papillomavirus positive women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:177–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Merikukka M, Kaasila M, Namujju PB, Palmroth J, Kirnbauer R, Paavonen J, Surcel HM, Lehtinen M. Differences in incidence and co-occurrence of vaccine and nonvaccine human papillomavirus types in Finnish population before human papillomavirus mass vaccination suggest competitive advantage for HPV33. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1114–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hariri S, Unger ER, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, Swan D, Patel S, Markowitz LE. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among females in the United States, the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2003-2006. J Infect Dis. 2011 Aug;204(4):566–73. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Dunne EF, Sternberg M, Markowitz LE, McQuillan G, Swan D, Patel S, Unger ER. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) 6, 11, 16, and 18 Prevalence Among Females in the United States--National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006: Opportunity to Measure HPV Vaccine Impact? J Infect Dis. 2011 Aug;204(4):562–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Castle PE, Schiffman M, Bratti MC, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Hutchinson ML, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S, Sherman ME, Kendall H, Viscidi RP, Jeronimo J, et al. A population-based study of vaginal human papillomavirus infection in hysterectomized women. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:458–467. doi: 10.1086/421916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Castle PE, Rodriguez AC, Porras C, Herrero R, Schiffman M, Gonzalez P, Hildesheim A, Burk RD. A comparison of cervical and vaginal human papillomavirus. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:849–855. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318064c8c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Kjaer SK, Breugelmans G, Munk C, Junge J, Watson M. Iftner T Population-based prevalence, type- and age-specific distribution of HPV in women before introduction of an HPV-vaccination program in Denmark. Int J Cancer. 2008 Oct 15;123(8):1864–70. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Wilkinson DE, Baylis SA, Padley D, Heath AB, Ferguson M, Pagliusi SR, Quint WG, Wheeler CM, Collaborative Study Group Establishment of the 1st World Health Organization international standards for human papillomavirus type 16 DNA and type 18 DNA. Int J Cancer. 2010 Jun 15;126(12):2969–83. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Muñoz N, Kjaer SK, Sigurdsson K, Iversen OE, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, Perez G, Brown DR, Koutsky LA, Tay EH, Garcia PJ, Ault KA, et al. Impact of human papillomavirus (HPV)-6/11/16/18 vaccine on all HPV-associated genital diseases in young women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:325–39. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.