Abstract

Social relationships can have considerable influence on physical and mental well-being in later life, particularly for those in long-term care settings such as assisted living (AL). Research set in AL suggests that other residents are among the most available social contacts and that co-resident relationships can affect life satisfaction, quality of life, and well-being. Functional status is a major factor influencing relationships, yet AL research has not studied in-depth or systematically considered the role it plays in residents’ relationships. This study examines the influences of physical and mental function on co-resident relationships in AL and identifies the factors shaping the influence of functional status. We present an analysis of qualitative data collected over a one-year period in two distinct AL settings. Data collection included: participant observation, informal interviews, and formal in-depth interviews with staff, residents, administrators and visitors, as well as surveys with residents. Grounded theory methods guided our data collection and analysis. Our analysis identified the core category, “coming together and pulling apart”, which signifies that functional status is multi-directional, fluid, and operates in different ways in various situations and across time. Key facility- (e.g., admission and retention practices, staff intervention) and resident-level (e.g., personal and situational characteristics) factors shape the influence of functional status on co-resident relationships. Based on our findings, we suggest strategies for promoting positive relationships among residents in AL, including the need to educate staff, families, and residents.

Keywords: Functional status, physical status, mental status, social relationships, assisted living

There is a well-established relationship between age and functional disability (Lewis & Bottomley, 2008). Consequently, greater life expectancy and the rapid aging of the population will result in increasing numbers of individuals with functional limitations. Many older adults will reach a point when they are no longer able to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) or live independently and some will require formal long-term care (LTC), including assisted living (AL). Theoretically, AL is based on a social model of care, which means it provides a home like environment and also promotes the principles of autonomy, privacy, and freedom of choice among residents (Carder, 2002), but in practice these principles are not followed universally by residents and workers in various AL settings (Roth & Eckert, 2011). Typically, AL settings provide watchful oversight, assistance with ADLs, and certain instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (e.g., medication management, meal preparation, and household cleaning) (Ball et al., 2000; Burdick et al., 2005).

In the United States, nearly one million individuals reside in AL settings and the number is expected to grow (Golant, 2008). Most AL residents are female, over 85 years old (Caffrey, Sengupta, Park-Lee, Moss, Rosenoff, & Harris-Kojetin, 2012), require assistance with approximately two ADLs (National Center on AL, 2009), and are without a partner or spouse (Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 2010). Nearly half of the AL population has Alzheimer’s disease or another type of dementia and other chronic diseases also are prevalent, including high blood pressure, heart disease, depression, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, COPD and related conditions, stroke, and cancer (Caffrey et al., 2012). These mental and physical conditions can affect an individual’s functional status, which influences social encounters and relationships (Iechovich & Ran, 2006).

When older adults move to AL, many maintain pre-existing social relationships with family, friends, and neighbors (Yamaski & Sharf, 2011), and some form new, sometimes meaningful, relationships with others (see for example, Ball et al., 2005; Eckert et al., 2009). AL residents have three main types of social relationships, including those with: (a) friends and family outside AL; (b) co-residents; and (c) paid caregivers (Ball et al., 2000; Burge & Street, 2010; Perkins, Ball, Kemp, & Hollingsworth, 2012; Tompkins et al., 2012). Family connections are very important for residents but, for the majority, family members are not available daily (Ball et al., 2000; 2005; Gaugler, 2007). Relationships with staff also carry importance (Ball et al., 2005; Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Hollingsworth, & King, 2009), but quite often staff members do not have adequate time to socialize with residents beyond their care-related interactions (Ball et al., 2009; Kemp, Ball, Hollingsworth, & Lepore, 2010). Residents’ relationships with other residents in AL can be of considerable importance in their lives and are predictors of life satisfaction or subjective well-being (Park, 2009; Perkins, Ball, Kemp, et al., 2012) and quality of life (Ball et al., 2000; 2005; Burge & Street, 2010; Street & Burge, 2012; Street, Burge, Quadagno, & Barrett, 2007). Previous qualitative research by Kemp, Ball, Hollingsworth, and Perkins (2012) indicates that co-resident relationships in AL can range from strangers to friends and include enemies and romantic type relationships with each resident experiencing a unique “social career” (i.e. their combined set of co-resident relationships and social trajectory in AL). This analysis identified a number of multi-level factors influencing co-resident relationships, including facility location and community connections, staff training and knowledge of residents, and resident tenure, gender, marital status, family involvement, and functional status. Residents’ functional status was a major individual-level factor influencing co-resident relationships. Functional impairment acted as a double-edged sword in that it promoted interactions through less impaired residents helping those with greater impairment, but it also hindered relationships because of such barriers as frequent medical appointments, decreased mobility, and communication problems.

AL residents often attach meaning to their relationships with those who are functionally similar (Ball et al., 2005; Perkins, et al. 2012). For example, residents with dementia may repetitively talk to each other without consequence (Ball et al., 2005) and sometimes they develop friendships (de Medeiros, Saunders, Doyle, Mosby, & Haitsma, 2012; Doyle, de Mederios, & Saunders, 2012). However, residents without dementia may not be tolerant of those with dementia, choosing to distance themselves, and in some instances form cliques based on functional status (Perkins et al., 2012; Roth & Eckert, 2011). Stigma often is attached to both physical and cognitive impairments in AL, which further impedes interactions and relationships among residents of varying functional abilities (Dobbs et al., 2008; Hrybyk et al., 2012; Perkins et al., 2012; Shippee, 2009).

Certain facility and resident factors are apt to shape the influence of functional status on co-resident relationships in AL. For instance, Doyle and colleagues’ (2012) study involving AL residents in an all-dementia care setting found environmental and organizational barriers to intergroup interactions. Locked doors represented an environmental barrier. Meanwhile, organizational factors related to staff preferences in completing tasks, included, for example, taking residents to their room after meals rather than providing opportunities to interact with each other (see also, Kemp et al., 2012).

Iecovich and Ran (2006) examined the inclination of healthy older adults to form relationships with older adults suffering from disability in two settings: one where those of differing functional statuses were integrated and another where they were segregated. Healthy older adults in the integrated facility tended to develop more negative attitudes toward their disabled peers compared to those living separately. One interpretation of this finding is that functionally-able older adults relate to others’ disabilities as possible outcomes of their own future, which could ultimately lead to death. Being fearful from this perspective would mean avoidance and suggests that individual attitudes and beliefs are apt to influence relationships. Other research indicates that some residents’ personal preferences may play a role, as some with poor functional status desire privacy, do not want to be bothered by others, and prefer to spend most of the time in their rooms (Ball et al., 2005; Perkins et al., 2012; Roth & Eckert, 2011).

Although existing research highlights the importance of co-resident relationships in AL, hinting at the complex influence of cognitive and physical functioning, research has yet to provide an in-depth understanding of how functional status affects these peer connections. Our present analysis seeks to: (a) understand how functional status influences co-resident interactions and relationships; and (b) identify the factors that shape how functional status affects social interactions and relationships. Addressing these aims will contribute to the development of strategies for promoting positive social experiences in AL and improving resident quality of life.

Design and Methods

We draw on data from the mixed-methods study, “Negotiating Residents’ Relationships in AL: The Experience of Residents” (PI, BLINDED). The overall aim of the study was to learn how to create an environment that maximizes residents’ ability to negotiate and manage their relationships with other residents. Qualitative and survey data were collected over a two-year period in eight distinct AL settings located in and around the metro-Atlanta area. A ninth home was used to collect additional resident survey data. BLINDED’s Institutional Review Board approved the project. For purposes of anonymity, we use pseudonyms for AL settings and participants.

Settings and Participants

Our present analysis uses qualitative data collected from two participating AL settings: Oakridge Manor and Garden House. Both settings have dementia care units (DCUs), however, as can be seen in Table 1, they differ along key dimensions including resident capacity, fees, ownership, and resident characteristics, including frailty levels and race. Oakridge Manor’s residents are all African American. Garden House residents are predominately white. The rationale for looking at an all-African American and a predominately white home is based on past research findings that show that residents, both as individuals and a group, attach different meanings to their situations based on race, class, culture, etc. and these meanings shape their experiences, including their social relationships (Ball et al., 2005; Perkins et al., 2012).

Table 1.

Select characteristics by home

| Characteristic | Oakridge Manor | Garden House |

|---|---|---|

| Average Census | 45 | 16 |

| Capacity | 55 | 18 |

| For Profit | Yes | Yes |

| Ownership | Corporate | Private |

| Monthly fee range | $ 2,700-$ 5,295 | $ 2,550-$ 2,900 |

| Race or culture | African American | Mostly white, African American (2) |

| %Men | 40% | 18% |

| % in wheelchairs | 22% | 0% |

| % with Dementia (AL) | 34% | 24% |

|

Dementia Care Unit

(DCU) |

yes | yes |

| Age Range | 54-102 | 65-96 |

| Number of Deaths | 5 | 1 |

Data Collection

Table 2 provides information about data collection by home. Data were collected in Oakridge Manor and Garden House during the first (2008-2009) and second year of the study (2009-2010), respectively. Data collection included: participant observation; informal interviews; formal in-depth interviews with staff, residents, administrators and visitors; and resident surveys. Researchers observed formal and informal activities and the physical and social environments. Observations and informal interviews were recorded in detailed field notes. Formal in-depth interviews with administrators (n=2), activity staff members (n=3), care staff members (n=3), and residents (n=12) were recorded, transcribed, and lasted on average an hour and a half. Administrator interviews were conducted during the first month of study. The remaining in-depth interviews with staff and residents were conducted after researchers had spent three months in each home. We asked administrators and care staff about co-resident relationships, factors influencing relationships, including policies and practices, the influence of activity programming, and their knowledge and attitudes about the importance of residents’ relationships. Cognitively-intact residents who had resided in the home for at least three months were invited to participate in surveys collecting information about their backgrounds, health status, support needs, and social support networks. Surveys also asked an open-ended question about co-resident relationships. These responses are included in the study’s qualitative database and are used in the present analysis. We also draw on field notes created through observations and informal interviews. Observations are a highly effective method of qualitative data collection “when the focus of research is on understanding actions, roles and, behavior” (Walshe, Ewing & Griffiths, 2012, p. 1048). Informal interviews also generate considerable information and contribute to “thick” data (Farrelly, 2013).

Table 2.

Data collection by type and location

| Data Type | Oakridge Manor |

Garden House |

Totals |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Participant observation

(hours/visits) |

578/178 | 154/47 | 732/225 |

| In-depth interviews (n=) | |||

| Administrator | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Activity Staff | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Care Staff | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Resident | 9 | 3 | 12 |

| Resident Surveys (n=) | 19 | 8 | 27 |

We used purposive stratified sampling (based on age, gender, race, and health and marital status) to identify cognitively-intact residents to participate in formal in-depth interviews. Interviews collected information about residents’ daily routines, social relationships with co-residents, staff, and persons outside AL settings, and the meanings they attach to the relationships. We used NVivo 9.0 – a software package for qualitative data management to help store and manage our qualitative data base and assist with analysis.

Data Analysis

We used grounded theory method (GTM) (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) to analyze our data. The goal of this approach is to develop theory based on the themes, concepts, and categories that are grounded in and emerge from the data. GTM involves three different levels of coding. Guided by our research questions and our data, we used initial or open coding to identify key concepts by examining the transcribed data line by line. We used the concept-indicator model, described by Strauss and Corbin (1998, p. 102) through which, “The data are broken down into discrete parts, closely examined, compared for similarities and differences, and questions are asked about the phenomena reflected in the data.” Next, we used axial coding to make connections between our categories and to understand how they are interrelated in “a process of relating categories to subcategories” (Strauss & Corbin, 1998, p. 847). In the next step, selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1998), we identified our core category, “Coming together and pulling apart” – a single category to which all other categories relate.

Results

Coming Together and Pulling Apart

Coming together and pulling apart signifies the key finding that functional status is multi-directional, fluid, and operates in different ways in various situations and across time. As will be seen, in certain circumstances, functional impairments can bring residents together physically, socially, and emotionally in positive ways and facilitate the formation of helpful and friendly relationships. Residents come together physically by means of helping each other and by engaging in different health-related conversations. Meeting, greeting, and asking about each other’s health and well-being can make residents “come together” socially. Sympathizing, showing concern, and sharing problems related to health also can bring them together emotionally. In other situations, functional status can “pull” residents apart physically, socially, and emotionally, creating self- or other-imposed barriers to the development of positive or meaningful co-resident relationships. Maintaining social distance, complaining, othering, showing frustration or intolerance for, and avoiding contact with each other are examples of how residents can be physically, socially, and emotionally “pulled apart” from one another as a result of variations in functional status. The influence of functional status on co-resident relationships is largely dependent on the existence, level, and type of impairment and health transitions faced by residents due to ongoing functional decline or acute health events, which for some led to moves to the DCU and temporary transfers to hospitals or nursing homes. Both physical and mental status affects the coming together and pulling apart process.

The influence of physical status

Residents experience a number of conditions that can influence their physical status and, hence, functioning. As presented in Table 3, among those living in Oakridge Manor and Garden House, the presence or absence of physical ailments, including vision, hearing and speech impairments, painful conditions (e.g., arthritis), and mobility-related problems, affected physical functioning and in turn influenced co-resident relationships and interactions; these conditions influenced AL residents’ coming together and pulling apart. Although Oakridge Manor residents were frailer than those in the Garden House, residents in both homes experienced a range of these conditions, often simultaneously.

Table 3.

Evidence of residents “coming together and pulling apart” based on physical conditions

| Physical status | Coming together | Pulling apart |

|---|---|---|

| Vision impairments |

|

|

| Mobility-related problems |

|

|

| Painful conditions |

|

|

| Hearing impairments |

|

|

| Speech impairments | No instances of coming together |

|

The influence of mental status

Residents’ mental status also had considerable influence on co-resident interactions and relationships. We present instances of coming together and pulling apart among residents on the basis of their mental status in Table 4. As shown, cognitive impairment, depression, and, although less common, mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, often acted as social barriers. Cognitive impairment among residents of Garden House and Oakridge Manor was caused primarily by dementia. Dementia-related behaviors manifest themselves in various ways, including the violation of social norms, repetitious conversations, difficulty comprehending, unpleasant (to others) eating behaviors, and inappropriate sexual behavior. Being mentally alert often promoted relationships among residents. Meanwhile, depression and schizophrenia, experienced by select Oakridge Manor residents, resulted exclusively in the process of “pulling apart.” These conditions acted as barriers to developing co-residents connections, particularly schizophrenia, which was responsible for periodic violent outbursts among the three residents with the diagnosis.

Table 4.

Evidence of residents coming together and pulling apart based on mental conditions

| Mental status | Coming together | Pulling apart |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive impairments |

|

|

| Mental illness- Schizophrenia | No instance of coming together |

|

| Mental illness- Depression | No instance of coming together |

|

Illustrative cases

In order to illustrate how residents’ overall functional status influences coming together and pulling apart, including how these processes are complex and can occur simultaneously, we offer four case examples, three from Oakridge Manor and one from Garden House. Mr. Carter illustrates the influence of multiple and severe physical impairments. Next, the case of Mr. Russell demonstrates the influence of physical and mental conditions combined. Third, the case of Mrs. Dixon reflects the experience of someone with mild cognitive impairment and high physical functioning. Finally, we consider Mrs. Forest, who experienced minimal physical impairment.

Mr. Carter

Residents in both settings frequently had multiple debilitating physical conditions, including Oakridge Manor resident, Mr. Carter, who was diabetic, totally blind, extremely hard of hearing, and used a wheelchair. His physical impairments brought him together with some of his fellow residents. Mr. Samson, who was more physically able, for example, noted he “liked Mr. Carter a lot” and had gotten to know him because he lived next door and usually helped him with “coming and going to the dining room” or other activities. He frequently was seen pushing Mr. Carter’s wheelchair or giving him verbal directions to navigate. These common occurrences routinely involved others, as the following field note passage suggests:

Mr. Carter was the first to head out of the sunroom. He did so with the guidance of those around him, including Mr. Samson and Ms. Garland. They instructed him by saying, “Go left,” or, “A little to the right.”

Mr. Carter also developed friendly relationships with his tablemates, Ms. Todd and Ms. Styles. Ms. Todd often helped him, “get acquainted” with the food and items at his place setting. Playful teasing and joking also transpired among residents, which could be used as a coping mechanism to minimize or redefine losses and aging-related changes. On Ms. Todd’s 91st birthday, Mr. Carter joked about his blindness, saying, “Wow. You sound so much younger.” Field note data further exemplify their relationship:

Ms. Todd said that Mr. Carter probably wouldn’t be down for dinner – he typically only comes to breakfast and lunch. Ms. Styles began to giggle and said that Mr. Carter seems to have a crush on Ms. Todd. Ms. Todd laughed and said it was because he couldn’t see her! She then said that she’s glad that he appreciates her “voice and brain.”

Mr. Carter’s physical impairments also were barriers to relationships and interactions, owing to other factors, often relating to other residents’ personal traits. Although Mr. Samson and Ms. Todd exhibited patience with Mr. Carter, not all residents did. Mr. Samuel, for example, often gave up talking to him and walked away during conversations. Being blind and in a wheelchair sometimes resulted in Mr. Carter accidently bumping into his fellow residents. In one instance he spilled water all over Mrs. Abbey, causing her to speak rudely to him and refer to him as a “blind man” and avoid future contact.

Mr. Russell

Mr. Russell was the frailest AL resident at Oakridge Manor. He was in a wheelchair and had advanced dementia that resulted in considerable speech difficulties that prevented most residents from understanding him. Mr. Russell spent most of his time sleeping in common areas, where he was placed by staff. His wife, Mrs. Russell, who also had dementia, but had high physical functioning, lived with him in AL. They usually were together, but Mrs. Russell sometimes ignored him, forgot her husband’s whereabouts or that she had husband and walked the halls, visiting with others and leaving him alone. The following field note excerpt illustrates a typical occurrence, “One of the caregivers pushed Mr. Russell into the sunroom and I pointed this out to Mrs. Russell… [She] sheepishly admitted with a giggle that she had ‘forgotten that [she] was even married.”

Mr. Russell often had coughing or choking attacks, particularly during meals or snack times. He was required to eat in the private dining room with other similar residents and eventually ate in the DCU. Most residents, particularly high functioning ones, found being around him objectionable, and some were intolerant. Mrs. Forest, for example, often would point her cane towards Mr. Russell and say to the care staff, “Move him.” Other residents largely ignored him. According to staff, he was a candidate for the DCU, but remained in AL because of “family issues” and because Mrs. Russell was not ready for the DCU and their children wanted them “together.” Overall, Mr. Russell’s high level of physical and mental impairment resulted in his being ostracized and almost entirely separated (i.e., pulled apart) from the other residents, including his wife (largely owing to her dementia).

Mrs. Dixon

Mrs. Dixon from Garden House had mild dementia, but was high functioning and remembered people, names, and events. Initially, she did not need any assistance walking, but, after a short-term hospitalization and increased frailty, she began using a walker with basket, seat, and brakes. Garden residents, including Mrs. Dixon, jokingly referred to their walkers as “Cadillacs.” Mrs. Dixon and fellow residents, Mrs. Fisher and Mrs. Ballard, formed a clique. The three were tablemates and in addition to meals, spent most of their time together, working on word puzzles and sitting in “their” area at the end of the hall. This group of women, all widows, had varying forms and degrees of dementia. Mrs. Fisher had severe dementia and the frailest. The activity director explained the group dynamics:

Mrs. Dixon and her two little partners … they all three have different versions of dementia… Mrs. Dixon is a real caregiver. If it hadn’t been for her, I guarantee you Mrs. Fisher’s kids would have gone crazy by now. Mrs. Dixon has taken up a lot of that time just sitting with her or working crosswords … .

Mrs. Dixon also “would stay with Mrs. Fisher and keep her company” when she was not feeling well. Eventually, both of Mrs. Dixon’s “partners” moved to the DCU where she visited.

Mrs. Dixon had good relationships with other residents, such as her “buddy” Mr. Potter who attempted to fill in for the loss of Mrs. Fisher and Mrs. Ballard after their move. He sat with Mrs. Dixon and the two remained friendly, despite Mr. Potter’s severe hearing impairment and frequent failure to observe accepted conversation conventions. Field note data illustrate:

Mr. Potter cut Mrs. Dixon off. He couldn’t hear her and didn’t realize she was talking. When they did chat, he had to ask her to repeat herself a number of times. This didn’t appear to frustrate Mrs. Dixon in the least.

Mrs. Dixon, because of her higher functional status and patient, caring ways had a good relationship with other Garden House’s residents.

Mrs. Forest

The absence of cognitive impairment, particularly combined with having few significant physical limitations, gave residents such as Mrs. Forest from Oakridge Manor considerable agency (i.e. control) over the process of coming together and pulling apart in co-resident relationships. She used a cane and had a history of multiple hip and knee surgeries, resulting in gait problems and joint pain, but her relatively good functional status meant she was active in facility life. She frequently attended exercise class, current events, and bible study and engaged socially with others. Despite her position as resident council president, she was most inclined to interact with residents with reasonably good functional statuses. She explained, “There are a few people that I can say I’m on the same page with them. So we share. But there aren’t too many of those here.”

Mrs. Forest had a small, but close-knit social circle that included her tablemates, Ms. Garland and Ms. Dalton. Over time, these friends experienced decline. Ms. Garland, for example, had a mini-stroke and was hospitalized. Mrs. Forest missed her friend and maintained daily contact with her by phone, keeping apprised of progress and treatments until her return. Meanwhile, Ms. Dalton’s moderate dementia began advancing. Mrs. Forest grew concerned about her well-being and began to monitor her, particularly her food intake at mealtimes. At the same time, however, Mrs. Forest began distancing herself from Mrs. Dalton, particularly outside of mealtimes. Oakridge Manor’s activity director explained:

Mrs. Dalton’s slipped a little bit now, so they don’t bother with her as much. They would save her a seat for exercise and make sure that no one sat there because it was Mrs. Forest, Ms. Garland, and Mrs. Dalton. But now she has declined so much, they don’t care whoever sits in that seat.

Mrs. Foster elaborated on this changing friendship:

Mrs. Dalton is not able to, as she used to be able, to chat with us. And particularly things that are current and we want to share—but she’s not able to because of the problems that she has. She’s not able to so therefore, she’s sits. And when we’re talking, I get the impression that she’s a little jealous of me—I used to spend more time with her, see. And she gets a little jealous and she will interrupt a conversation that Mrs. Garland and I are having.

Mrs. Forest’s mobility and high cognitive functioning allowed her to help others when she chose, including Mrs. Garland. As suggested, this assistance waned over time. She began helping Ms. Parker and Ms. Petit, who were not cognitively impaired, but experienced considerable physical pain. Ms. Petit’s diagnosis of terminal cancer brought the two women close together, and Mrs. Forest visited her each night in order to pray together. Mrs. Forest commented on helping others, “I just enjoy knowing that someone needs me. And whatever little that I can do for them I want to do it.” However, she continued, “if I can help somebody, I don’t mind. I really don’t. Yet, sometimes it gets a little bit, you know, tiresome.” Helping simultaneously brought Mrs. Forest together with those she chose to help, but also gave her an identity, responsibilities, and burdens that set her apart physically and socially from residents without the ability or desire to help.

The data presented thus far illustrate how the presence or absence of certain conditions influence the process of coming together and pulling apart among co-residents in AL. Data also suggest that this process often is situational, and functional status does not always operate in universal ways, which alludes to the existence of additional intervening factors.

Factors Shaping the Influence of Functional Status on Co-Resident Relationships

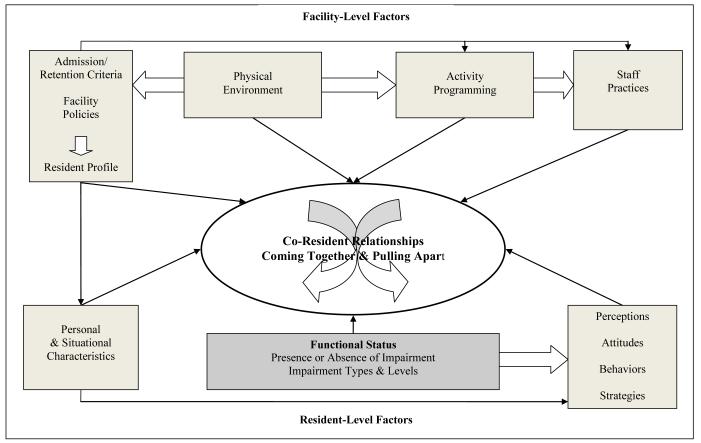

Our analysis identified a host of intersecting facility- and resident-level factors that combine to influence the relationship between functional status and co-resident connections (see Figure 1). As shown, facility-level factors, such as admission/retention criteria and facility policies, have an influence on resident profiles and therefore on residents’ functional status. Activity programming is further dependent on this profile and influences residents’ relationships and levels of integration of those with variable functional states. As well, the availability of space for organized activities is important and, thus, the physical environment, including size, has impact. Staff practices can influence the connection between physical and mental status on co-resident relationships. Hence, facility-level factors are interrelated and also are connected to resident-level factors, such as individual characteristics, attitudes, perception, behaviors and strategies, and social involvement. Our explanatory model depicts the interrelationship between these key factors and their influence on the core category, “coming and pulling apart.” These key influences are elucidated below.

Figure 1.

The Process of Coming Together and Pulling Apart

Facility-level factors

Garden House and Oakridge Manor had important differences regarding residents’ attitudes and behaviors related to other residents’ functional status. Relative to Oakridge Manor, Garden House residents had more tolerance and patience for those with poor functional status. They expressed fewer negative attitudes and behaviors, and coming together between residents was a more frequent occurrence. Because of closer relationships, including many that began decades earlier in the small tight-knit town prior to living at Garden House, the administrator described the setting as a “big family” - a term many residents also used. Although Oak Ridge Manor caters to African American elders and their families, providing an overall a sense of community based on commonality of race, religion, and cultural values, such commonality was not always sufficient to maintain a constant sense of community or camaraderie. Residents with good functional status were less familiar with and tolerant of residents with poorer functional status. Rather, other facility-level factors proved more influential.

Physical environment

A facility’s physical environment, including size and layout, is an important factor that shapes the influence of functional status on relationships and the core category, coming together and pulling apart. As indicated, Garden House is smaller and has a much lower resident capacity than Oakridge Manor, which facilitated opportunities for social interaction, thus promoting greater familiarity. Moreover, Garden House is a single-story structure with a long hallway shared by most residents. The hallway is spacious enough to allow residents with walkers to walk side-by-side. The smaller size, with the dining, activity, and TV areas located relatively close to living spaces, permitted residents to congregate and interact in common areas regularly and without having to travel too far from their apartments. The highly accessible, spacious, and attractive front porch was popular among residents and had comfortable furniture and also provided protection from sun and rain. It was popular for “sitting”, “visiting”, and “porch talk.”

Oakridge Manor, physically larger and with more residents, is a multistory building with elevators. The dining room and most other common spaces are located on the first floor, and the majority of resident rooms are on the second. Because almost a fourth (22%) of residents used wheelchairs, congestion was common surrounding elevator access, which led to gathering and friendly exchanges and greetings. Such gathering also sometimes led to social conflict. Crowded elevators increased the risk of accidental and unwanted physical contact. One resident, for example, routinely complained about being “hit” or “run into” by “old people,” especially those in wheelchairs and walkers. Yet, spacious public areas, including a sunroom, patio, hallways, and activity rooms offered greater accessibility. Residents often gathered and interacted in these areas, which promoted relationships.

Admission and retention criteria

Admission and retention criteria exert a primary influence on the resident profiles of both facilities. Compared to Oak Ridge Manor, Garden House had stricter admission and retention criteria with regard to functional status. The administrator explained that only residents who can ambulate 50 feet “on their own steam,” whether in a wheelchair or not, and transfer independently were admitted. Residents were discharged when their care needs exceeded the ability of staff to accommodate. She explained, “The benchmark for me is when my staff’s just killing themselves moving the person around or trying to do too much.” AL residents often were moved to the DCU when they were still cognitively receptive but experienced physical decline, were incontinent, neglected their hygiene, behaved in socially inappropriate ways, wandered, and required too much staff time during meals. Garden House’s AL section, consequently, had few residents with significant cognitive or physical impairments. No AL residents used a wheelchair, although many used walkers and canes.

Oakridge Manor’s rules of admission permitted any residents allowed under Georgia’s personal care home regulations and who did not pose potential dangers to themselves or others. AL residents who wandered, were anti-social, whose care needs exceeded the AL staff’s ability to meet, and who had significant behavioral problems, such as aggression or resisting care, usually were transferred to the DCU. However, some residents with severe physical and cognitive impairments, including Mr. Russell, remained in AL for various reasons, including, lack of available beds, family member resistance, and the use of a private care aide.

Additional facility policies

Policies also interact with and can shape resident situations and the resident profile, as well as the process of coming together and pulling apart. One example is the policy of allowing residents to have private care aides or hospice caregivers. Oakridge Manor allowed a privately paid care aide to spend the day with Mrs. Parker, who was confined to a wheelchair, had a sling on her right arm, and slept most of the time. As will be seen, the presence of this aide facilitated and constrained Mrs. Parker’s interactions with fellow residents. Facility rules and policies also influenced activity programming in each home, which often reflects residents’ overall abilities.

Activity programming

Each facility had activity programs that reflected the range of resident characteristics, facility size, and staffing. Garden House offered various activities for individuals and groups. Group activities included the movie club, exercise class, puzzle playing, and routine resident outings. Certain activities (e.g., movies and exercise sessions) were resident run. The relatively high functioning Garden House residents rarely complained about the functional level required by the planned activities. Nevertheless, problems sometimes occurred during the resident-run movie activity, typically related to the range of hearing abilities, which led to disagreements and to pulling apart of certain residents as the following field note passage indicates:

Ms. Butler didn’t stay to watch the movie, but came running out of the TV room saying it was too loud. She’d complained that Mr. Potter had it up too loud. The activity director thinks Ms. Butler needs to keep her hearing aids at home when she watches the movie.

At Oakridge Manor organized activities included: Bingo, Pokeno, bible study, choir practice, exercise sessions, and monthly community outings. Staff ran most, though not all activities, which mainly targeted the lowest functioning residents. Higher functioning residents often complained and blamed the residents with lower functional status for what they perceived as inferior activity programming. The following passage shows instances of social distancing and “othering”, including “us” and “them” attitudes, which are indicative of pulling apart among certain residents but also of coming together:

Mrs. Dalton began to talk about not being happy with the activities that were offered… Mrs. Dalton frequently distances herself from the more disabled residents. She continued, “Most of the activities are very childish, like those nursery rhymes.”

Eventually as Mrs. Dalton’s declined, she became one of the more functionally limited residents and was unable to participate in most of the activity programing.

Staff practices

Various factors related to facility staff shape the influence of functional status on co-resident relationships. Influential staff practices included encouraging residents to participate in activities and facilitating connections between co-residents. For instance, the following field note passage outlines the actions of one staff member, Lori, who knew her residents well and encouraged interaction between Ms. Rose, a resident with dementia who kept mostly to herself, and an incoming resident with limited mobility, Ms. Post:

Lori approached Ms. Rose while pushing a frail looking woman in a wheelchair. She told her that Ms. Post had also been a nurse and she thought it would be nice for the two of them to meet and talk. Ms. Rose’s face lit up and the two women immediately began talking.

Staff also intervened in conflicts. They changed dining room seating arrangements, redirected the attention of problem-causing residents, and sometimes scolded residents or halted arguments. Field note data from Oakridge Manor illustrate an instance of staff intervention in an escalating disagreement and frustration between residents of different functional levels:

During a lull in the game, Mrs. Scott noticed that there was a bingo chip under Mr. Bass’ chair. She pointed this out to him many times. Each time Mr. Bass said that either he or the activity person would get it later when they were finished and cleaning up. Just minutes later, Mrs. Scott again said, “Do you know there is a chip under your seat? You’d better pick it up.” Mr. Bass clenched his fist and shook it out in front of him – as if he was toying with the idea of punching her. He yelled back “Do you know you come downstairs in your nightgown??” Both activity staff in unison told them to calm down and stop fighting.

In extreme instances, the administrator responded to conflict related to cognitive decline or behavioral issues by relocating residents to the DCU.

As noted, AL residents in Garden House required less hands-on care than Oakridge residents. Oakridge Manor residents with good functional status sometimes complained that they did not receive quality of care because staff paid greater attention to lower functioning residents, a situation leading to pulling apart, as illustrated in the following field note excerpt:

Mrs. Forest then leaned over and said in a hushed voice while pointing to the man in the wheelchair, “He is the problem.” Ms. Garland and Mrs. Forest were very upset for a couple of reasons…they both voiced concerns that the amount of care that “certain residents” require diminishes the quality of care that can be provided to the higher functioning residents.

Resident-level factors

Various resident-level factors shape the influence of functional status on co-resident relationships. These factors directly influence the coming together and pulling apart of resident relationships or interact with facility-level factors. Our analysis suggests the key resident factors include: personal and situational characteristics, perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and strategies.

Personal and situational characteristics

Personal characteristics include, for example, gender and marital status. Facility-assigned characteristics, such as being tablemates or neighbors through apartment location, reflect situational characteristics. Both join to shape the influence of functional status on the process of coming together and pulling apart.

Gender shaped the influence of functional status on co-resident relationships as sometimes same-gendered residents tried harder to make accommodations for physical limitations. For example, Mr. Wright and Mr. Potter, the only men in Garden House for over a year, were determined to communicate despite their poor hearing. Field note data illustrate one of their many attempts to interact: “Mr. Wright’s hearing is worse than Mr. Potter’s. The two of them don’t get mad at each other because of their hearing but just keep asking the other to repeat themselves when necessary.” Mr. Wright noted multiple times that they had to stick together being the “only two roosters in the hen house.”

Marital status influenced the association between functional status and co-resident ties. Being married, particularly if one spouse is the primary caregiver for the other, can negatively influence co-resident relationships in AL. The following Oakridge Manor field note passage illustrates a sequence of events after visiting between Mr. Mann and his tablemate was interrupted by Mrs. Mann’s care needs:

Eventually Mr. Mann came back to his table and his tablemate. He explained that he had to take his wife to the bathroom and she’d decided not to come back. He was gathering up some things from the table to take upstairs to their apartment.

Mr. Mann’s participation in social engagement and activities were influenced by his wife’s care needs.

In the absence of heavy caregiving, spouses sometimes relied on one another in social situations, especially when both had dementia. Field note data describe the Smythes’ participation in a group discussion:

As usual, Mr. & Mrs. Smythe sat side by each appearing to function as a team. This is evident whenever either of them has difficulties remembering or hearing. They usually ask the other, who sometimes, but definitely not always, remembers or had understood what had been said.

Having a spouse afforded certain couples the potential to compensate for and sometimes overcome communication barriers related to functional impairment if they we able and willing to work together.

Having a private care aide, which was dependent on a resident’s access to adequate financial resources, also influenced coming together and pulling apart. For instance, Mrs. Parker’s private care aide allowed her to remain in her room most of the time, even for meals, which restricted contact with other residents. The presence of the aide also limited Mrs. Parker’s need and opportunity for help from other residents. But, sometimes this caregiver took Mrs. Parker to activities she would not otherwise attend, facilitating contact with co-residents. Furthermore, having the aide allowed Mrs. Parker to age in place thereby extending contact with other residents.

In both Garden House and Oakridge Manor situational characteristics were influential as residents engaged more often with those in closer physical contact, including their neighbors. Such proximity facilitated behaviors related to functional status, such as helping, which tended to happen more regularly between neighbors. Sometimes, proximity led to pulling apart because of functional ability alongside personal preferences and facility practices. In the Oakridge Manor, for instance, Mrs. Forest did not tolerate the behaviors of her schizophrenic neighbor, Mrs. Ikin who, according to Mr. Mann, would “go off” and “turn everybody off.” A staff member commented, “We had to move Ms. Ikin [to the DCU] because Mrs. Forest did not want her up here. She couldn’t tolerate her behavior.”

Being tablemates shaped the influence of functional status on coming together and pulling apart. Sharing a table promoted familiarity, monitoring, and concern for others and often promoted helping behaviors, even among those with cognitive impairment. The executive director of Oakridge Manor explained this dynamic:

We have, at one of our men’s tables… a resident who has to have lactose-free milk and someone with severe, severe dementia, I was pouring the milk and I was about to pour it in his cereal out of a little container, he says, “No, no, no, no he has to have the special milk”… And at another table where they are, I find that as the dementia has progressed, at one table there is less verbal communication, but there’s still that level of dependency because I see that when they’re there, they eat better as a group.

Yet being tablemates also could make more evident certain functional limitations. In Oakridge Manor, residents with swallowing or choking problems or who were considered messy eaters by their fellow residents often were relocated by staff to the private dining area or to the DCU.

Residents who relocated permanently to the DCU in Oakridge Manor were not visited by those who lived in AL, even in cases where residents had been friendly. According to the administrator, “I don’t think they like to see them after they’ve gone down like that because it probably reminds them of what may happen to them.” In Garden House, a few AL residents continued their relationships through visits, though not daily, and patterns changed over time. Mrs. Taylor visited her long childhood friend Mrs. Wren when she first moved to the DCU, but was thinking of discontinuing these visits because Mrs. Wren’s hearing had become so bad and communication so difficult. Meanwhile, the following field note excerpt tells of Mrs. Dixon’s experience when Mrs. Ballard and Mrs. Fisher moved to Oakridge’s DCU:

She told me that her two friends had moved to “the other side.” I asked her if she’d been to visit. She said she had, but she didn’t like going over there. Mrs. Dixon is afraid if she goes over too much to visit they will move her over [too].

Mrs. Dixon’s reluctance to visit her DCU-dwelling friends highlights the influence of her beliefs regarding what might become of her, but also speaks to her caring ways.

Residents’ perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and strategies

The presence or absence of functional impairments often influenced residents’ perceptions, attitudes, strategies and behaviors towards each other. For instance, high-functioning Mrs. Forest held negative attitudes towards residents with physical and cognitive impairments, including those with high levels of both, such as Mr. Russell. She regularly gave such residents “disapproving looks”, demonstrating little tolerance. Although she helped certain residents, she often was frustrated with their behaviors and chose to maintain social and sometimes physical distance from them. In the case of Mrs. Blake who always forgot her room number, Mrs. Forest got “really annoyed” and wouldn’t “give her a pen or tell her her room number.” Yet, unlike Mrs. Forest, certain residents were understanding, compassionate, and patient with their lower functioning peers and their attitudes encouraged greater forbearance, especially regarding those with cognitive impairments. Mrs. Hall of Oakridge Manor observed, “We should be sensitive to people who are experiencing dementia.”

Residents’ strategies also shape the influence of functional status on co-resident interactions and relationships. The underlying strategy of some higher functioning residents was to help others, particularly residents in wheelchairs, which helped pass time and provided meaningful activities, often missing in AL. Mr. Toft said that, “there wasn’t much to do at Oakridge Manor.” Consequently, he spends much of his day “helping those who can’t help themselves”, which is an instance of residents coming together on the basis of differing functional statuses. Another resident, who found helping meaningful, said, “If I can do anything to help somebody, it’s pleasing to me.” Alternatively, preferring to interact at a different level, some residents with good functional status sought out and attempted to make connections with staff members, avoiding co-resident interactions.

Discussion

This qualitative analysis explored the influence of functional status on older adults’ social relationships in two diverse AL settings. By utilizing GTM principles, we offer the core category, “coming together and pulling apart,” as an explanatory framework for elucidating the variability in co-resident relationships created by functional status. This finding further signifies that the influence of functional status is multi-directional, fluid, and varies by situation and across time. Our conceptual model illustrates the direct and indirect association of facility- and resident-level factors with functional status and its influence on co-resident relationships. Findings advance existing literature by providing an in-depth understanding of how functional status operates as a factor in creating or hampering co-resident relationships in AL.

The concept, “coming together and pulling apart” is novel and advances knowledge by describing and explaining the process of variability among co-resident relationships in AL. The influence of functional status on the process of coming together and pulling apart was dependent in large part on the presence or absence of certain physical and mental impairments, and, among those with impairment, level and type of impairment, and health-related transitions. As research shows, residents with good functional status (i.e. those with few, if any, impairments who are relatively independent) often have negative attitudes and perceptions of and behave poorly towards those with poor functional status (Iecovich & Ran, 2006).

Our analysis confirms that residents with good functional status often distance themselves from residents with poor functional status and avoid contact (Ball et al., 2005; Perkins et al., 2012). However, we also found that residents with few impairments can come together with residents of poor functional status by “neighboring” (see Kemp et al, 2012), including asking about other’s health and well-being, showing concern, and offering advice. As Perkins et al. (2012) note, helping also can be a way for residents to distinguish themselves from those with lower levels of functional ability. In such cases, coming together and pulling apart occur simultaneously and hints at power relationships and a hierarchy based on functional status.

Existing literature indicates that certain kinds of physical impairments, such as hearing, speech, or mobility-related problems typically act as communication barriers and, hence, relationship barriers (Hubbard, Tester, & Downs, 2003; Kemp et al., 2012). However, in this study coming together by helping in the context of hearing loss or other impairments also was observed. Humor facilitated coming together among residents, especially surrounding aging and health conditions. Our findings support existing research in residential care settings suggests that humor, joking, and playful teasing can be used by residents to “make light of their own and each other’s aging bodies” and can strengthen co-resident relationships (Hubbard et al., 2003, p. 104). The value of humor also is found among older adults in general (Damianakis & Marziali, 2011).

Research in nursing homes (Gubrium, 1975) and AL (Dobbs et al., 2008; Perkins et al., 2012) provides evidence that social exclusion and stigmatization of mentally impaired residents can act as barriers to the development of co-resident relationships. Our analysis confirms these findings and shows residents without cognitive impairment often were intolerant towards those who were cognitively impaired. Intolerance sometimes led to conflicts and disagreements among residents and hence restricted relationship prospects. In very rare instances, coming together was seen among residents in terms of helping memory-impaired residents locate missing items, reminding them of certain activities, joking around about the memory problems, and encouraging residents with poor appetite to eat, a finding not evident in the existing literature. As others note, the similarity of functional status in terms of residents having cognitive impairments can lead to friendly relationships (Ball et al., 2005; Doyle et al., 2012) and to the formation of cliques (Perkins et al., 2012). We observed cognitively impaired residents spending time together and found, as did de Mederios and colleagues (2012), friendships and caring relationships can develop within such groups. Residents’ social careers (Kemp et al., 2012) change over time and often are affected by health-related transitions, such as decline and moves to the DCU. For residents fortunate enough to forge positive relationships, particularly friendships in AL, decline typically had a negative influence. Friendships in Oakridge Manor ended when residents moved to the DCU. In Garden House, this was not always the case.

Serious mental health problems such as schizophrenia affect approximately 8% of the AL population in the United States (CDC, 2010). These conditions tend to be more common in small, low-income, personal care homes, where admission criteria are more lenient; studies also indicate that these illnesses affect co-resident relationships (see for e.g., Ball et al., 2000; 2005; Perkins et al., 2004; Perkins, Ball, Whittington et al., 2012). In this analysis, the presence of severe mental illness occurred in the larger home and exclusively pulled residents apart. Behavioral problems associated with schizophrenia scared many residents. This condition ultimately hindered relationship development, leading to the isolation of mentally ill residents. Meanwhile, residents with depression often remain in their rooms most of the time or do not socialize when in public spaces and, because of lack of self-esteem and energy, avoid activities, distance themselves from co-residents and hence engage in the process of pulling apart. Depression is not a minor issue in AL; approximately 28% of the AL population has a diagnosis of depression nationwide (Caffrey et al., 2012).

As noted by Kemp et al (2012), multilevel factors influence co-resident relationships. In the present analysis we identify key facility- and resident-level factors that directly and indirectly shape the influence of functional status on ties and offer an illustrative conceptual model to show how factors work together. Physical environment is among the key facility factors. We confirmed what Perkins, Ball, Whittington et al. (2012) found: residents with dementia often are socially accepted in smaller facilities, such as the Garden House, and excluded in larger ones, such as Oakridge Manor.

The present study also supports earlier work on the influence of marital status on relationships. Couples have built-in companionship, but often one spouse acts as a caregiver, which can limit social opportunities in AL (Kemp, 2008; Kemp et al., 2012; Moss & Moss, 2007). Our data further suggest that spouses can help to compensate for functional decline and promote social interaction among residents, but only insofar as spouses are aware of and communicate with one another. This may also be true of friends, siblings or other dyads.

Existing literature suggests that attending meals and activities is important for promoting resident interactions (Ball et al., 2005; Kemp et al., 2012; Park, 2009). The present study further elaborates how functional status affects social involvement and the process of coming together and pulling apart. In general, residents with good functional status were involved socially by attending meals and participating in activities. Residents with poor functional status sometimes were social isolated from others, as they were less involved in activities and not as integrated into mealtime conversations as their high-functioning peers. Yet, mealtimes also provided opportunities for helping and facilitated socialization with tablemates.

AL residents typically are older and frailer, requiring greater ADL assistance than in past years (Golant, 2008). These patterns will influence relationships among residents and AL experiences. Changes to policy and practice in AL may help improve co-resident relationships and we offer recommendations. First, residents, staff, and families should be educated about common physical and mental impairments. Information could be disseminated through easily understood written materials, videos, or presentations from knowledgeable community members (e.g., physicians or nurses). Education might help residents understand other’s conditions and perhaps make them more sympathetic and tolerant. Staff knowledge about residents’ impairments and symptomatology could help them react to residents in more supportive ways. Although they receive little to no training on residents’ social needs (Ball, Hollingsworth, & Lepore, 2010), staff should be aware of the important role they can play in facilitating co-resident relationships. Families play a key role in the development of co-resident relationships (Kemp et al., 2012) and sometimes promote stigmatization of cognitively impaired residents (Dobbs et al., 2008). Educating family members also would be useful for encouraging co-resident relationships among those of variable functional statuses.

Another recommendation pertains to the use of assistive devices. For instance, residents with hearing impairments, such as Mr. Potter, could be encouraged and assisted if necessary to use their hearing aids in order to reduce communication barriers. Measures also could be taken to provide support to residents who might not have the resources to buy devices or who do not know how to use them properly.

Residents, whenever realistic and desirable, should be encouraged to participate in group exercise sessions and other activities. Existing literature shows that incorporating walking programs in the daily schedule of AL residents can improve their chances of social interactions, physical health, and higher perceptions of life (Lu et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2003). In general, activities should also be devised according to residents’ needs, preferences, abilities, and interests by adopting an individualized approach. Activity-related evaluation should be completed regularly so that programming can reflect changes in residents’ preferences and functional ability. Measures also could be taken to prevent or reduce conflicts among residents with variable functional levels during group activities. For instance, activity staff could facilitate peer helping.

AL facilities should design common areas to be spacious enough to accommodate the use of assistive devices. Having spaces to congregate, especially before and after meals is important. Roth & Eckert (2011) find that AL facilities sometimes attempt to prevent residents from congregating in common areas. Yet doing so should be reconsidered as it creates unnecessary barriers to co-resident interaction. Creating spaces that are large enough, comfortable and personal, and allow residents to congregate could promote interactions and should be a goal for administrators, architects, and designers. Lu and colleagues (2011) recommend corridors with hand rails and wide enough for two walkers, flooring safe for walking, and areas for resting as features that could further promote social relationships among residents.

Our research advances existing knowledge but it is not without limitations. First, our study did not capture all functional impairments, especially the influence of less visible impairments, including those related to arthritis, congestive heart failure, HIV/AIDS or other conditions that might influence social relationships. Moreover in some of our other study homes, incontinence was highly influential on co-resident interactions (see Blinded). Residents often isolate themselves when they have conditions that carry stigma (Ball et al., 2004; Perkins et al., 2012). Thus, unanswered questions about the influence of the full range of conditions need to be explored. Next and related, the present analysis also only draws on qualitative data gathered in two of our nine study homes. Future analysis of quantitative data will help to further tease apart the influence of functional status on co-resident relationships and will explore, “coming together and pulling apart” using the full sample and its wider variety of settings. Advancing knowledge and improving social relationships are exceedingly important tasks as the AL industry grows and the resident population increases in average age and frailty and correspondingly, has greater care needs.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this article was supported by the National Institute for Aging at the National Institutes for Health (1R01 AG021183 to M.M. B.), A version of this paper was presented at the 33rd Annual Meeting of the Southern Gerontological Society in Nashville, TN. Thank you also to Mark Sweatman, Emmie Cochrane Jackson, Shanzhen Luo, Ailie Glover, Yarkasah Paye, Vicki Stanley, Amanda White, Terri Wylder, Karuna Sharma, and Sophie Carrssow for their assistance in the research process. We also are very grateful to all those who participated in our AL research and generously gave of their time and shared their experiences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ball MM, Hollingsworth C, Lepore MJ. Hiring and training workers. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline Workers in Assisted Living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2010. pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL. Overview of research. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline Workers in Assisted Living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2010. pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Independence in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2004;18(4):467. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Communities of care: Assisted living for African American elders. University Press; Johns Hopkins: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Perkins MM, Patterson VL, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Quality of life in assisted living facilities: Viewpoints of Residents. The Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2000;19:304–325. [Google Scholar]

- Burdick DJ, Rosenblatt A, Samus QM, Steele C, Baker A, Harper M, Mayer L, et al. Predictors of functional impairment in residents of assisted-living facilities: the Maryland assisted living study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2005;60:258–264. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge S, Street D. Advantage and choice: Social relationships and staff assistance in assisted living. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2010;65B:358–369. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp118. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey C, Sengupta M, Park-Lee U, Moss A, Rosenoff E, Harris-Kojetin L. Residents Living in Residential Care Facilities: United States, 2010. 2012 NCHS Data Brief, 91. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db91.html. [PubMed]

- Carder PC. The social world of assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2002;16:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control . National Survey of Residential Care Facilities, public use data file. DHHS; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsrcf/nsrcf_questionnaires.html. [Google Scholar]

- Damianakis T, Marziali E. Community- dwelling older adults’ contextual experiencing of humor. Ageing and Society. 2011;31:110–124. [Google Scholar]

- de Medeiros K, Saunders PA, Doyle PJ, Mosby A, Haitsma KV. Friendships among people with dementia in long- term care. Dementia. 2012;11:363–381. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D, Eckert J, Rubinstein B, Keimig L, Clark L, Frankowski A, Zimmerman S. Ethnographic study of stigma and ageism in residential care or assisted living. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):517–526. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle PJ, de Medeiros K, Saunders PA. Nested social groups within the social environment of a dementia care assisted living setting. Dementia. 2012;11:383–399. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Carder PC, Morgan LA, Frankowski AC, Roth EG. Inside assisted living: The search for home. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly P. Choosing the right method for a qualitative study. British Journal of School Nursing. 2013;8:93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE. Families and assisted living. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:83–89. doi:10.1093/geront/47.Supplement_1.8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golant SM. The future of assisted living residences: A response to uncertainty. In: Golant SM, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: A vision for the future. The Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2008. pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium J. Living and dying at Murray Manor. St. Martin’s Press; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hrybyk R, Rubinstein RL, Eckert JK, Frankowski AC, Keimig L, Nemec M, et al. The dark side: stigma in purpose built senior environments. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2012;26:275–289. doi: 10.1080/02763893.2012.651384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard G, Tester S, Downs MG. Meaningful social interactions between older people in institutional care settings. Ageing & Society. 2003;23:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Iecovich C, Ran OL. Attitudes of functionally independent residents toward residents who were disabled in old age homes: The role of separation versus integration. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2006;25:252–268. doi: 10.1177/0733464806288565. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Hollingsworth C, Perkins MM. Strangers and friends: Residents’ social careers in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;67(4):491–502. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs043. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL. Negotiating transitions in later life: Married couples in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2008;27:231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CB, Bottomley JM. Geriatric Rehabilitation: A clinical Approach. Pearson; New Jersey: 2008. Pathological manifestations of aging; pp. 67–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CB, Bottomley JM. Geriatric Rehabilitation: A clinical Approach. Pearson; New Jersey: 2008. Neurological considerations; pp. 281–342. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Rodiek SD, Shepley MM, Duffy M. Influences of physical environment on corridor walking among assisted living residents: Findings from focus group discussions. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2011;30:463–484. [Google Scholar]

- Moss SZ, Moss MS. Being a man in long term care. Journal of Aging Studies. 2007;21:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Assisted Living Assisted living resident profile. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.ahcancal.org/ncal/resources/Pages/ResidentProfile.aspx.

- Park NS, Zimmerman S, Kinslow K, Shin HJ, Roff LL. Social engagement in assisted living and implications for practice. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2012;31:215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Park NS. The relationships of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28:461–481. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Combs BL. Managing the needs of low-income board and care residents: A process of negotiating risks. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:478–495. doi: 10.1177/1049732303262619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Kemp CL, Hollingsworth C. Social relations and residents health in assisted living: An application of the Convoy Model. The Gerontologist. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns124. (in press) doi: 10.1093/geront/gns124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C. Relational autonomy in assisted living: A focus on diverse care settings for older adults. Journal of Aging studies. 2012;26:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.001. doi: 10. 1016/j.jaging. 2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth EG, Eckert j. K. The vernacular landscape of assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2011;25:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.005. doi 10.16/j.jaging.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippee TP. “But I am moving: Residents’ perspectives on transitions within a continuing care retirement community. The Gerontologist. 2009;49:418–427. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp030. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Street D, Burge S. Residential context, social relationships, and subjective well-being in assisted living. Research on Aging. 2012;34:365–394. doi:10.1177/016402755114233928. [Google Scholar]

- Street D, Burge S, Quadagno J, Barrett A. The salience of social relationships for resident well-being in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2007;62:129–34. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L, Whittington F, Hollingsworth C, Ball M, King S, Patterson V, Neel AR. Assessing the effectiveness of a walking program on physical function of residents living in an assisted living facility. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2003;20:15–26. doi: 10.1207/S15327655JCHN2001_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins CJ, Ihara ES, Cusick A, Park NS. “Maintaining connections but wanting more:” Continuity in familial relationships among assisted living residents. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2012;55:249–261. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2011.639439. doi:10.1080/01634372.2011.639439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walshe C, Ewing G, Griffiths J. Using observation as a data collection method to help understand patient and professional roles and actions in palliative care settings. Palliative Medicine. 2012;26:1048–1054. doi: 10.1177/0269216311432897. doi:10.1177/0269216311432897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaski J, Sharf BF. Opting out while fitting in: How residents make sense of assisted living and cope with community life. Journal of Aging Studies. 2011;25:13–21. [Google Scholar]