Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Since July 2010, the National Advisory Committee on Immunization of Canada has recommended rotavirus vaccination for all healthy infants. However, before implementing this vaccine in routine health programs, Canadian provinces need to establish current epidemiological data on rotavirus-associated acute gastroenteritis (AGE).

METHODS:

A retrospective cohort study of children <5 years of age with AGE from 2002 to 2008 was performed in Eastern Townships, Quebec (population in 2006: 298,780). Data were collected on visits to outpatient clinics, emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations (standard and short-stay units) and nosocomial AGE. The winter residual estimation and Brandt methods were used to estimate the proportion of AGE attributable to rotaviruses.

RESULTS:

During the six-year study period, a total of 1435 hospitalizations, 3631 ED visits and 6220 ambulatory care visits were attributed to AGE. The specific rotavirus burden was estimated to be 449 to 666 for hospitalizations, 1050 to 1361 for ED visits and 1633 to 1687 for outpatient visits. The epidemic curve showed a periodicity with higher incidence in March and April. Short-stay unit hospitalizations represented 58% of all hospitalizations. The annual incidence rate of rotaviruses was estimated to be 50 to 74 per 10,000 children for hospitalizations, 117 to 152 per 10,000 children for ED visits and 182 to 188 per 10,000 children for outpatient visits.

CONCLUSION:

Most available retrospective studies probably underestimate rotavirus-associated hospitalizations because they do not take into account short-stay unit hospitalizations. Furthermore, these data on emergency and outpatient visits provide an exhaustive appraisal of the rotavirus burden, which serves as crucial information for the evaluation of immunization programs.

Keywords: Burden of disease, Children, Gastroenteritis, Health system, Rotavirus

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Depuis juillet 2010, le Comité consultatif national de l’immunisation recommande de vacciner tous les nourrissons en santé contre le rotavirus. Cependant, avant d’ajouter ce vaccin aux programmes de vaccination systématique, les provinces canadiennes doivent obtenir des données épidémiologiques à jour sur la gastro-entérite aiguë (GEA) associée au rotavirus.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont effectué une étude de cohorte rétrospective auprès d’enfants de moins de cinq ans ayant eu une GEA entre 2002 et 2008 en Estrie, au Québec (population de 298 780 habitants en 2006). Ils ont colligé les données aux consultations externes, au département d’urgence (DU), chez les patients hospitalisés (unités standard et de courte durée) et relatives aux cas de GEA nosocomiales. Ils ont utilisé l’estimation hivernale résiduelle et les méthodologies de Brandt pour évaluer la proportion de GEA attribuables aux rotavirus.

RÉSULTATS :

Pendant la période d’étude de six ans, 1 435 hospitalisations, 3 631 consultations au DU et 6 220 consultations externes étaient attribuables à la GEA. On estimait que le fardeau propre à la GEA se situait entre 449 et 666 pour les hospitalisations, entre 1 050 et 1 361 pour les consultations au DU et entre 1 633 et 1 687 pour les consultations externes. La courbe épidémique a révélé une périodicité à l’incidence plus élevée en mars et avril. Les hospitalisations de courte durée représentaient 58 % de toutes les hospitalisations. On estime que le taux d’incidence annuel des rotavirus oscille entre 50 et 74 cas sur 10 000 enfants sur le plan des hospitalisations, entre 117 et 152 cas sur 10 000 enfants sur le plan des consultations au DU et entre 182 et 188 cas sur 10 000 enfants sur le plan des consultations externes.

CONCLUSION :

Selon toute probabilité, la plupart des études rétrospectives disponibles sous-estiment le nombre d’hospitalisations associées au rotavirus parce qu’elles ne tiennent pas compte des hospitalisations dans les unités de courte durée. De plus, ces données sur les consultations externes et à l’urgence fournissent une évaluation détaillée du fardeau du rotavirus, qui contient de l’information capitale pour évaluer les programmes de vaccination.

Rotaviruses are the leading cause of infectious diarrhea among children <5 years of age worldwide (1). They are a major cause of infectious mortality in low-income countries and a significant cause of morbidity in developed countries (2). In Canada, during the winter months, rotaviruses are responsible for 37% to 72% of hospitalizations, and 18% to 47% of emergency department (ED) and outpatient visits for acute gastroenteritis (AGE) (3–5). Two oral live rotavirus vaccines are now licensed for pediatric use: RotaTeq (Merck & Co Inc, USA), a pentavalent human-bovine reassortant vaccine, and Rotarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals Inc, United Kingdom), a monovalent vaccine derived from a human G1P rotavirus strain. In a phase 3 clinical trial, vaccine efficacy against rotavirus-associated AGE was shown to be between 74% and 87% for the first rotavirus season, after the administration of a complete course of vaccination (6–8). First impact studies of rotavirus vaccination conducted in the United States and Europe revealed a significant decrease of hospitalizations associated with rotavirus AGE (9–12). Recently, both the WHO and the National Advisory Committee on Immunization recommended the routine application of the rotavirus vaccine for all healthy infants (13,14).

Currently, in Canada, the number of rotavirus-associated AGE-related hospitalizations have been estimated to be between 19 and 45 cases per 10,000 children <5 years of age (4–15). Core studies have focused only on standard hospitalizations in pediatric units; no data have been published on short-stay unit (SSU) hospitalizations, an emerging alternative for AGE management in the past 10 years. In addition, no recent population study has evaluated the impact of rotavirus-associated AGE on ED and outpatient clinic visits during the same period.

Depending on AGE severity, its management has involved four levels of health care resources: outpatient visits, ED visits, SSUs and standard pediatric unit hospitalizations. In Quebec, provincial databases (Régie de l’Assurance Maladie du Québec [RAMQ], Med-Echo) can provide data on outpatients, ED visits and hospitalizations in standard pediatric units. However, no data regarding SSU hospitalization are available. At the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (CHUS [Sherbrooke, Quebec]), a local data warehouse (Centre Informatisé de Recherche Évaluative en Services et Soins de Santé [CIRESSS]) contains exhaustive data on all hospitalizations (standard and SSU), which gives us the unique opportunity to describe the entire burden of AGE.

It is important to better define prevaccine burden to evaluate postlicensure vaccine impact and to establish a baseline before the widespread use of rotavirus vaccines. The aim of the present study was to assess the burden of rotavirus-associated AGE before the implementation of the vaccine, at every level of the health care system in Eastern Townships, a representative region of Quebec.

METHODS

Study population

All children from one to 59 months of age, living in Eastern Townships, with an AGE diagnosis and whose parents had sought medical evaluation from November 1, 2002 through October 31, 2008, were included in the present study. Records for children with a diagnosis of AGE were identified on the basis of the following International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision and 10th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10CM) codes: AGE of determined etiology (bacterial; 001 to 005/A01 to A03, A05 excluding 003.2/A02.2 localized Salmonella infections and 008.0 to 008.5/A04), parasitic (006 to 007/A06 to A07, excluding codes 006.2 to 006.6/A06.3 to A06.7 [amebic abscess and localized amebiasis]), viral (008.6 and 008.8/A08.0 to A08.5), AGE of undetermined etiology but presumed to be infectious (009.0 to 009.3/A09) or noninfectious (558.1 to 558.9/K52.8 to K52.9) and AGE not otherwise specified (787.91). Primary and secondary diagnoses were considered for hospitalizations and ED visits; for outpatient visits, only the primary diagnosis was considered. For all hospitalized patients, demographic, clinical and laboratory data were collected. Denominators (all children living in Eastern Townships during the study period) were obtained from the Quebec Institute of Statistics. The study protocol was approved by the CHUS Ethics Committee.

Data sources

Data from hospitalizations and from ED and outpatient visits, respectively, were obtained from one local data warehouse (CIRESSS) and from one provincial database (RAMQ). CIRESSS combines extensive data from computerized patient records with data on diagnoses (ICD-9/10CM). It contains exhaustive data on all hospitalizations (standard units and SSU) and ED visits at the CHUS, a 712-bed academic tertiary care centre. Because the CHUS holds 100% of acute care pediatric beds in the region (Eastern Townships population in 2006, 298,780; area, 10,134 km2), the ascertainment rate for rotavirus-associated AGE necessitating a hospital admission is reflected in the CHUS rotavirus AGE case numbers. In Quebec, all residents have free access to medical care and the majority of family physicians and specialists are reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis for outpatient and ED visits. Quebec’s public health insurance database (RAMQ) contains computerized records of all claims with a main diagnosis coded according to ICD-9/10CM.

Rotavirus estimate

Routine microbiological testing was not performed for all children included in the present study. To evaluate the proportion of AGE attributable to rotaviruses, the present study used two previously validated methods: the winter residual estimation (WRE) (16,17), which is calculated on the basis of the difference between winter and summer AGE cases, and the Brandt method (18), which involves the application of proportions of confirmed rotavirus-associated AGE as obtained during an eight-year surveillance study. According to the literature, these methods yield similar results (15,19,20). For the indirect residual method, winter months were defined as the months of December through May. The remaining months were designated as summer months. The proportion of AGE attributable to rotaviruses in children <5 years of age was determined by subtracting the baseline AGE observed in the summer months from that seen in the winter months. The Brandt method included use of the frequency of rotavirus identification by electron microscopy in children with AGE during an eight-year period in Washington, DC (USA). The monthly rotavirus rate determined by Brandt et al (18) was applied to the total AGE rate identified in the study involving children <5 years of age for each month in a given year, then summed to provide a total number of AGE attributable to rotavirus. Subsequently, yearly rates of rotavirus infections were determined by using the estimated population of children <5 years of age for each year.

The present study estimated the annual incidence rate of rotavirus infections among children with AGE who required medical attention in the following health care settings: hospitalizations in standard units and SSUs (<24 h), ED visits and outpatient visits. These categories were not exclusive and a child could have experienced more than one infection during the first years of life.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, USA). Frequency rates were obtained for all AGE, and the rotavirus annual incidence rates were estimated into the four health care setting categories, which were not mutually exclusive. Available demographic data were compared between hospitalizations in the standard units and SSUs. Comparisons were assessed for statistical significance at P=0.05 (two-sided) using the Student’s t test for continuous variables, the χ2 test for categorical variables or the Fisher’s exact test when numbers were small.

RESULTS

All-cause AGE

During the study period, 1725 episodes of AGE were identified with appropriate discharge codes, but 290 were excluded (92 were not Eastern Townships residents, 83 were nosocomial AGE, 53 had no AGE criteria, 29 had chronic AGE and 33 had other exclusion criteria). SSU hospitalization was preferentially used (n=837; 58%) when patients needed to be admitted for AGE (Table 1). Annually, the number of hospitalizations ranged between 186 and 300, and the annual incidence rate for AGE was 160 per 10,000 children <5 years of age (Table 2). The majority of AGE-related hospitalizations (n=910; 63%) and visits (n=6280; 64%) occurred in children <2 years of age. Stool specimens analyzed for rotavirus were higher in the standard hospitalization group (41% versus 17%; P<0.001) but positive results were higher in the SSU group (41% versus 32%; P<0.001). Mean hospital length of stay was 53 h (interquartile range 40 h to 81 h) in the standard hospitalization group and 23 h (interquartile range 18 h to 28 h) in the SSU group. Intravenous rehydration was similar in both groups but more children were transferred to the intensive care unit after being hospitalized in the standard unit; there were no AGE-related deaths (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of children <5 years of age hospitalized because of acute gastroenteritis

| Standard unit (n=598) | Short-stay unit (n=837) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age <2 years | 383 (64) | 527 (63) | ns |

| Prematurity | 77 (12.8) | 85 (10.1) | ns |

| Intravenous rehydration | 583 (97.4) | 823 (98.3) | ns |

| Stool specimens analyzed for rotavirus | 243 (40.6) | 142 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| Positive results | 79 (32.5) | 59 (41.5) | <0.001 |

| Admission to the intensive care unit | 18 (3) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ns |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified. ns Not statistically significant

TABLE 2.

Annualized number and incidence rate/10,000 for children <5 years of age hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis, emergency department visits and outpatient visits in Eastern Townships, Quebec

| Year |

Hospitalization

|

Emergency department visit

|

Outpatient visit

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Rate/10,000 | n | Rate/10,000 | n | Rate/10,000 | |

| Nov 2002–Oct 2003 | 261 | 177 | 639 | 434 | 1235 | 839 |

| Nov 2003–Oct 2004 | 204 | 138 | 629 | 425 | 1165 | 787 |

| Nov 2004–Oct 2005 | 282 | 191 | 663 | 450 | 1068 | 724 |

| Nov 2005–Oct 2006 | 186 | 126 | 522 | 355 | 834 | 567 |

| Nov 2006–Oct 2007 | 300 | 197 | 708 | 465 | 1090 | 717 |

| Nov 2007–Oct 2008 | 202 | 130 | 470 | 304 | 828 | 536 |

| Total | 1435 | 160 | 3631 | 405 | 6220 | 694 |

Nov November; Oct October

In total, 3631 children visited an ED and 6220 children visited an outpatient clinic for AGE-associated illness. Annually, the number of visits for AGE ranged from 470 to 708 in the ED and from 828 to 1235 in outpatient clinics. Average annual incidence rate was 405 per 10,000 and 694 per 10,000 children <5 years of age for both types of visits, respectively (Table 2).

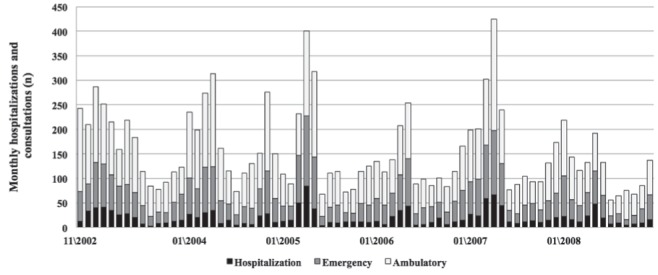

Seasonal variability was similar for AGE-associated health care use, with increasing numbers of visits and hospitalizations during the winter and a significant year-to-year variability. Each year, a peak for AGE-related hospitalizations and visits was generally observed in March and April (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Number of monthly acute gastroenteritis-related hospitalizations, emergency visits and outpatient visits during a six-year period among children <5 years of age in Eastern Townships, Quebec

Rotavirus-associated AGE

During the study period, 385 of 1516 (25%) hospitalized children underwent stools tests for rotaviruses, of which 138 (36%) were positive. On the basis of this subgroup, monthly analysis confirmed that the epidemic period for rotaviruses was from December to May. The present study estimated, by using the WRE and Brandt indirect methods, respectively, that rotaviruses accounted for 31% and 46% of all AGE-related hospitalizations, 29% and 38% of all AGE-related ED visits, and 26% and 27% of all AGE-related outpatient visits. The annual overall estimated incidence rate was 50.1 and 74.3 rotavirus-associated hospitalizations per 10,000 children <5 years of age, according to indirect estimation methods (WRE and Brandt, respectively), 117.1 and 151.8 rotavirus-associated ED visits per 10,000 children, and 182.3 and 188.2 outpatient visits per 10,000 children (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Annualized number and incidence rate per 10,000 for children <5 years of age with rotavirus hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis (AGE), emergency department visits and outpatient visits in Eastern Townships, Quebec

| Epidemic season |

Annual number of visits for AGE

|

Rotavirus estimation, WRE method

|

Rotavirus estimation, Brandt method

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n (%) | Rate/10,000 | n (%) | Rate/10,000 | |

| Hospitalizations | |||||

| Nov 2002–Oct 2003 | 261 | 143 (55) | 97.2 | 87 (33) | 59.2 |

| Nov 2003–Oct 2004 | 204 | 48 (24) | 32.4 | 62 (30) | 41.7 |

| Nov 2004–Oct 2005 | 282 | 153 (54) | 103.8 | 93 (33) | 63.2 |

| Nov 2005–Oct 2006 | 186 | 72 (39) | 48.9 | 50 (27) | 28.6 |

| Nov 2006–Oct 2007 | 300 | 166 (55) | 109.1 | 104 (35) | 58.2 |

| Nov 2007–Oct 2008 | 202 | 84 (42) | 54.4 | 53 (26) | 34.0 |

| Total | 1435 | 666 (46) | 74.3 | 449 (31) | 50.1 |

| Emergency department visits | |||||

| Nov 2002–Oct 2003 | 639 | 237 (37) | 161.1 | 189 (30) | 128.6 |

| Nov 2003–Oct 2004 | 629 | 151 (24) | 102.0 | 183 (29) | 123.7 |

| Nov 2004–Oct 2005 | 663 | 292 (44) | 198.0 | 187 (28) | 126.9 |

| Nov 2005–Oct 2006 | 522 | 150 (29) | 102.0 | 135 (26) | 92.0 |

| Nov 2006–Oct 2007 | 708 | 349 (49) | 229.5 | 229 (32) | 150.6 |

| Nov 2007–Oct 2008 | 470 | 182 (39) | 117.8 | 126 (27) | 81.6 |

| Total | 3631 | 1361 (38) | 151.8 | 1050 (29) | 117.1 |

| Outpatient visits | |||||

| Nov 2002–Oct 2003 | 1235 | 297 (24) | 201.8 | 297 (24) | 201.9 |

| Nov 2003–Oct 2004 | 1165 | 250 (22) | 168.9 | 344 (30) | 232.3 |

| Nov 2004–Oct 2005 | 1068 | 298 (28) | 202.1 | 245 (23) | 166.2 |

| Nov 2005–Oct 2006 | 834 | 180 (22) | 122.3 | 205 (25) | 139.6 |

| Nov 2006–Oct 2007 | 1090 | 432 (40) | 284.0 | 332 (31) | 218.6 |

| Nov 2007–Oct 2008 | 828 | 230 (28) | 148.8 | 210 (25) | 135.9 |

| Total | 6220 | 1687 (27) | 188.2 | 1633 (26) | 182.3 |

Nov November; Oct October; WRE Winter residual estimation

DISCUSSION

The present study clearly depicts the burden of rotavirus-associated AGE at each level of care in Eastern Townships, a representative region in Quebec. Our study population (the CHUS holds 100% of acute care pediatric beds in the Eastern Townships region) enabled us to perform an exhaustive analysis of rotavirus-associated AGE among children <5 years of age. Depending on the estimation method and after including SSU, approximately one of 27 to one of 40 children will require hospitalization attributable to rotavirus-associated AGE by their fifth year of life. The impact on ED and outpatient services is indeed higher, with a five-year cumulative estimated incidence of one of 13 to one of 17 for ED visits and one of 10 to one of 11 for outpatient visits. Most visits involved children <2 years of age, which demonstrates that younger patients are more susceptible to complications.

The present study is the first to evaluate the incidence of rotavirus-associated AGE in the entire health care system in a defined population during several rotavirus seasons in Canada. A major strength of the present study was the extensive study period of six years, thereby limiting the effects of seasonal variations. Many prospective studies on rotavirus AGE are limited by data collected within a single year (3–5). Furthermore, the present study took into account SSU hospitalizations, whereas other available retrospective studies probably underestimate rotavirus hospitalizations because they do not include this cohort.

These data can be used to extrapolate the burden of rotavirus-associated AGE in Quebec and in Canada (Table 4). When using the 2006 cohort of children in Quebec and Canada (2006 is the last census conducted in Canada), the present study estimated that a total of 1885 to 2792 hospitalizations, 4434 to 5799 ED visits and 6853 to 7112 outpatient visits were attributable to rotavirus infections per year in Quebec. For Canada, the present study estimated that a total of 8452 to 12,523 hospitalizations, 19,888 to 26,008 ED visits and 30,737 to 31,897 outpatient visits were attributable to rotavirus infection each year. This type of analysis is mostly exploratory because spatial and temporal variations are highly possible. However, because no pan-Canadian prospective surveillance system to monitor these infections exists, this type of estimation is highly valuable to weight the potential burden of rotavirus AGE on Canadian health services.

TABLE 4.

Extrapolation of the estimated annual burden of rotaviruses on the entire health system in Quebec and Canada among children <5 years of age

| Annual incidence (Eastern Townships, Quebec) | Annual events in Quebec* | Annual events in Canada† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations (standard and short-stay units) | 50–74/10,000 | 1885–2792 | 8452–12523 |

| ED visits | 117–152/10,000 | 4434–5799 | 19,888–26,008 |

| Outpatient visits | 180–188/10,000 | 6853–7112 | 30,737–31,897 |

Denominator from the Institute of Statistics, Quebec. Data were collected from the last census (2006: 376,936),

Denominator from the Institute of Statistics, Canada. Data were collected from the last census (2006: 1,690,540 children <5 years of age). ED Emergency department

The present study’s annual incidence rates for hospitalizations were significantly higher than those of previously reported American and Canadian retrospective data based on administrative sources (4,15,19,20), which reported rates of between 19 and 45 per 10,000 children <5 years of age. This is probably because they did not take into account SSU hospitalizations. However, annual incidence rates for ED and outpatient visits were similar to those of other publications from the United States (64 to 150 per 10,000 for ED visits and 145 to 401 per 10,000 for outpatient visits), whereas no Canadian data were available for comparison (21–23). Other publications in Canada, in which active laboratory surveillance was used, report that rotaviruses contribute to approximately 37% to 71% of hospitalizations, 44% to 47% of ED visits and 18% to 20% of outpatient visits for AGE (3–5). The range of results reported in these studies may be explained by the fact they were conducted during only one epidemic season; it is well known that interyear variations are important in rotavirus AGE (18–24).

The main limitations of the present study are its retrospective design and use of indirect methods of rotavirus-associated AGE estimation. However, for hospitalizations, the WRE method has been found to be accurate when compared with active surveillance measures (25). This method is more disputed for ambulatory and ED visit rotavirus AGE estimations. In these settings, probably not all of the excess AGE cases are caused by rotaviruses; several other viruses may be responsible for AGE not requiring hospitalizations. The second method (Brandt) also may be questionable when estimating rotavirus AGE-associated ED and outpatient visits because the original study conducted by Brandt et al (18) involved only hospitalizations. However, results are consistent in both indirect methods (WRE and Brandt). Geographical and seasonal variations may impact the accuracy of extrapolations from local studies to a national level, but the present study’s estimations are concordant with precedent studies in other developed countries, particularly for ED and outpatient settings (21–23). Moreover, an estimate based on a six-year period is less subject to year-to-year variations, a reality in rotavirus AGE.

CONCLUSION

The present study is the only study that assessed the burden of rotavirus-associated AGE at every level of the health care system in Canada for an extensive six-year period, taking into account inter-annual variations. The present study’s data on SSU hospitalizations, ED and outpatient visits provide an exhaustive appraisal of the rotavirus burden. For public health experts, the present study suggests that the number of hospitalizations attributable to rotaviruses may be substantially higher than that of the previously reported Canadian study (3–5,15). Furthermore, the large burden of rotavirus disease in ambulatory settings should be taken into account in any studies that focus on the impact of rotavirus vaccination. At the time of implementing rotavirus vaccination in Canada, these results provide crucial information for the evaluation of immunization programs by health authorities.

Footnotes

GRANT SUPPORT: The study was funded by an unrestricted grant from Merck Frosst and by the University of Sherbrooke (Sherbrooke, Quebec). Merck Frosst did not have any role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data.

DISCLOSURES: Dr Gagneur has received research grants from pharmaceutical companies including Wyeth, Merck and Sanofi-Pasteur MSD. Dr Gagneur has received honoraria from pharmaceutical companies including Wyeth, Merck, Sanofi-Pasteur MSD and GlaxoSmithKline for educational presentations and congress presentations. Dr Louis Valiquette has served on advisory boards for Oryx, Iroko, Abbott and Wyeth and has received compensation to conduct clinical trials involving antibacterials from GlaxoSmithKline, Genzyme, Wyeth, Pfizer, BioCryst, Trius, Cempra, Optimer and Arpida. The remaining authors have no conflicting interests to declare.

CONTRIBUTIONS: Arnaud Gagneur, Sylvain Bernard and Louis Valiquette: study concept, study supervision, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. Vincent Nault: statistical analysis. Philippe De Wals, Corentin Babakissa, Claude Cyr and Thérèse Côté Boileau: study concept. All authors: critical revision of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresse JS, Glass RI. Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:304–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parashar UD, Hummelman EG, Bresee JS, Miller MA, Glass RI. Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:565–72. doi: 10.3201/eid0905.020562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford-Jones EL, Wang E, Petric M, Corey P, Moineddin R, Fearon M. Hospitalization for community-acquired, rotavirus-associated diarrhea: A prospective, longitudinal, population-based study during the seasonal outbreak. The Greater Toronto Area/Peel Region PRESI Study Group. Pediatric Rotavirus Epidemiology Study for Immunization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:578–85. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.6.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivest P, Proulx M, Lonergan G, Lebel MH, Bedard L. Hospitalisations for gastroenteritis: The role of rotavirus. Vaccine. 2004;22:2013–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford-Jones EL, Wang E, Petric M, Corey P, Moineddin R, Fearon M. Rotavirus-associated diarrhea in outpatient settings and child care centers. The Greater Toronto Area/Peel Region PRESI Study Group. Pediatric Rotavirus Epidemiology Study for Immunization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:586–93. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vesikari T, Matson DO, Dennehy P, et al. Safety and efficacy of a pentavalent human-bovine (WC3) reassortant rotavirus vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:23–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vesikari T, Karvonen A, Prymula R, et al. Efficacy of human rotavirus vaccine against rotavirus gastroenteritis during the first 2 years of life in European infants: Randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370:1757–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61744-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linhares AC, Velazquez FR, Perez-Schael I, et al. Efficacy and safety of an oral live attenuated human rotavirus vaccine against rotavirus gastroenteritis during the first 2 years of life in Latin American infants: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. Lancet. 2008;371:1181–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagneur A, Nowak E, Lemaitre T, et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on hospitalizations for rotavirus diarrhea: The IVANHOE study. Vaccine. 2011;29:3753–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson EJ, Rupp A, Shulman ST, Wang D, Zheng X, Noskin GA. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on hospital-acquired rotavirus gastroenteritis in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e264–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanquet G, Ducoffre G, Vergison A, et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on laboratory confirmed cases in Belgium. Vaccine. 2011;29:4698–703. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tate JE, Panozzo CA, Payne DC, et al. Decline and change in seasonality of US rotavirus activity after the introduction of rotavirus vaccine. Pediatrics. 2009;124:465–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotavirus vaccines: An update. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2009;84:533–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Updated Statement on the use of Rotavirus Vaccines. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2010;36:1–37. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v36i00a04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buigues RP, Duval B, Rochette L, et al. Hospitalizations for diarrhea in Quebec children from 1985 to 1998: Estimates of rotavirus-associated diarrhea. Can J Infect Dis. 2002;13:239–44. doi: 10.1155/2002/723804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho MS, Glass RI, Pinsky PF, Anderson LJ. Rotavirus as a cause of diarrheal morbidity and mortality in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:1112–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.5.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin S, Kilgore PE, Holman RC, Clarke MJ, Gangarosa EJ, Glass RI. Trends in hospitalizations for diarrhea in United States children from 1979 through 1992: Estimates of the morbidity associated with rotavirus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:397–404. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandt CD, Kim HW, Rodriguez WJ, et al. Pediatric viral gastroenteritis during eight years of study. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:71–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.1.71-78.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charles MD, Holman RC, Curns AT, Parashar UD, Glass RI, Bresee JS. Hospitalizations associated with rotavirus gastroenteritis in the United States, 1993–2002. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:489–93. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000215234.91997.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer TK, Viboud C, Parashar U, et al. Hospitalizations and deaths from diarrhea and rotavirus among children <5 years of age in the United States, 1993–2003. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1117–25. doi: 10.1086/512863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flores AR, Szilagyi PG, Auinger P, Fisher SG. Estimated burden of rotavirus-associated diarrhea in ambulatory settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e191–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yee EL, Staat MA, Azimi P, et al. Burden of rotavirus disease among children visiting pediatric emergency departments in Cincinnati, Ohio, and Oakland, California, in 1999–2000. Pediatrics. 2008;122:971–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pont SJ, Grijalva CG, Griffin MR, Scott TA, Cooper WO. National rates of diarrhea-associated ambulatory visits in children. J Pediatr. 2009;155:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato T, Nakagomi T, Naghipour M, Nakagomi O. Modeling seasonal variation in rotavirus hospitalizations for use in evaluating the effect of rotavirus vaccine. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1468–74. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu VP, Staat MA, Roberts N, et al. Use of active surveillance to validate international classification of diseases code estimates of rotavirus hospitalizations in children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:78–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]