Abstract

Aerococcus viridans is an infrequent human pathogen and few cases of infective endocarditis have been reported. A case involving a 69-year-old man with colon cancer and hemicolectomy 14 years previously, without recurrence, is reported. A diagnosis of native mitral valve endocarditis was established on the basis of clinical presentation, characteristic echocardiographic findings and pathological specimen examination after urgent valve replacement. A viridans endocarditis appears to be particularly virulent, requiring a surgical approach in four of 10 cases reported and death in one of nine. Given the aggressive nature of A viridans endocarditis and the variable time to diagnosis (a few days to seven months), prompt recognition of symptoms and echocardiography, in addition to blood cultures, should be performed when symptoms persist.

Keywords: A viridans, Endocarditis, Mitral valve

Abstract

L’Aerococcus viridans est un pathogène humain peu fréquent qui s’associe à peu de cas déclarés d’endocardite infectieuse. Les auteurs présentent le cas d’un homme de 69 ans atteint d’un cancer du côlon et ayant subi une hémicolectomie 14 ans auparavant, sans récurrence depuis. Les médecins ont posé un diagnostic d’endocardite de la valvule mitrale naturelle d’après la présentation clinique, les observations échocardiographiques caractéristiques et l’examen des échantillons pathologiques après un remplacement valvulaire d’urgence. L’endocardite à A viridans semble particulièrement virulente. Elle a exigé une approche chirurgicale dans quatre des dix cas déclarés, et a suscité un décès dans un cas sur neuf. Étant donné le caractère agressif de l’endocardite à A viridans et le délai variable avant le diagnostic (de quelques jours à quelques mois), il faut en reconnaître rapidement les symptômes et ajouter une échocardiographie aux hémocultures en cas de persistance des symptômes.

Aerococcus viridans is a microaerophilic, Gram-positive, catalase-negative coccus with a strong tendency toward tetrad formation. It has growth characteristics similar to that of streptococci and enterococci. Aerococci are environmental isolates ubiquitously found in the air of housing premises (hospitals, schoolrooms, factories, offices), dust, raw vegetables, animals and animal products, as well as human skin (1). Three Aerococcus species have been implicated as rare pathogens in humans. Aerococcus urinae causes endocarditis (2–11), septicemia, urinary tract infections/urosepsis, pyelonephritis, spondylodiscitis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, peritonitis, lymphadenitis and soft tissue infections (12–25). Aerococcus sanguinicola causes bacteremia (26), endocarditis (26), urosepsis (26) and cholecystitis (26). A viridans causes urinary tract infections (27,28), bacteremia, endocarditis (Table 1), para-aortic abscess, meningitis, spondylodiscitis and septic arthritis (29–44). Risk factors for A viridans systemic infections (bacteremia/endocarditis) have not yet been fully elucidated; however, granulocytopenia, oral mucositis, prolonged hospitalization, previous antibiotic therapy, invasive procedures and implantation of foreign bodies have been associated with severe infections with A viridans (36). Previous valvular abnormalities, such as rheumatic valve disease, have been described as predisposing conditions for infective endocarditis (38). Reports in which no obvious immunosuppressive factor could be found are rare. This was the case in our patient.

TABLE 1.

Review of published reports on Aerococcus viridans endocarditis

| Case | Age, years/sex | Clinical presentation | Diagnosis | Treatment | Complications | Resistant | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 49/M | Subacute (7 months): Fever; polymyalgia; mild AR murmur | 14×15 mm AV veg on TEE | Ampicillin/amikacin | AV thickening/mild AR. Medical Rx. No relapse at 18 months | Quinolones/aminoglycosides | 40 |

| 2 | 62/M | Subacute (1 month): Fever; weight loss; dyspnea/MR murmur; Janeway lesion; splenomegaly | 13×12 mm veg on anterior mitral leaflet | Ceftriaxone/amikacin | Splenectomy for splenic abscesses. MVR. No relapse at 12 months | Quinolones | 40 |

| 3 | 40/M | Subacute (3 weeks): Fever/fatigue; arthralgias; Osler nodes | 14×11 mm veg at aortic cusp on TEE | Penicillin G/gentamicin | Medical Rx. No relapse at 38 months | 40 | |

| 4 | 45/F | Acute (3 days): Fever; dyspnea; ataxia; Janeway lesion; MR murmur; CHF | 7×6 mm veg on anterior leaflet and posterior leaflet 5×3 mm | Penicillin G/gentamicin | MVR | 40 | |

| 5 | 10/M | Subacute (1 month): Fever; dyspnea; arthralgia; hematuria; clubbing; MR murmur; CHF | Veg on mitral leaflet | Norfloxacin/amikacin | Compensated MR. Medical Rx | Penicillin/ampicillin/cefotaxime/gentamicin | 41 |

| 6 | 28/M | Subacute (6 months): Fever; rheumatic complaints; hematuria; AR murmur | Flail aortic leaflet with veg | Penicillin G/gentamicin | AoVR. No relapse at 6 months | 44 | |

| 7 | 44/M | Acute (few days): Fever; hematuria; splenomegaly; AR murmur | Not reported | Penicillin/streptomycin | CHF 6 weeks post discharge. Sudden death | 42 | |

| 8 | 54/M | Subacute (4 months): Fever; back pain; systolic murmur | Billowing leaflet | Penicillin | Medical Rx. No relapse at 10 weeks | Sulfonamide | 43 |

| 9 | 58/M | Acute (4 days): Fever; pyuria/hematuria; altered LOC; diastolic murmur | 10 mm veg on noncoronary cusp of AV on TEE | Cefotaxime/vancomycin | Medical Rx. Well at 3 months outpatient follow-up | Chloramphenicol/clindamycin/erythromycin/gentamicin/TMP-SMX | 39 |

| 10 | 44/F | Subacute (2 weeks): Fever; AF; systolic murmur at AV area | Rheumatic AV and MV; moderate MS; oscillating mass 11×10 mm, MG 35 mmHg across AV on TEE | Ampicillin/sulbactam/gentamicin | Enlarging veg (21×10 mm) causing AV obstruction s/p 3 weeks of oral antibiotics requiring AoVR/MVR | 38 |

AF Atrial fibrillation AoVR Aortic valve replacement; AR Aortic regurgitation; AV Aortic valve; CHF Congestive heart failure; F Female; LOC Level of consciousness; M Male; MG Mean gradient; MR Mitral regurgitation; MS Mitral stenosis; MV Mitral valve; MVR Mitral valve replacement; Ref Reference; Rx Treatment; s/p Status post; TEE Transesophageal echocardiogram; TMP-SMX Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; Veg Vegetation

Studies from clinical cases and specimens demonstrated that strains are generally susceptible to β-lactam antimicrobials (eg, penicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid) and vancomycin (40–44). On the other hand, resistance was found to quinolones, tetracycline, clindamycin and streptomycin (40–44); penicillin resistance was reported in two instances to levels >250 μg/mL (44). Resistance to gentamicin has also been reported occasionally for human clinical strains (39,41).

The present article describes a case of A viridans endocarditis in a patient with no obvious risk factor for immunosuppression or previous valvular abnormality.

CASE PRESENTATION

The patient was a 69-year-old man with colon cancer and hemicolectomy 14 years previously, without recurrence. He was admitted to hospital after five weeks of general deterioration, fatigue, weight loss, chills and sweats. He reported undergoing a dental cleaning one month before admission. Physical examination revealed a man with a heart rate of 82 beats/min, blood pressure of 122/86 mmHg, a respiratory rate of 22 breaths/min and a temperature of 37.2°C. His lungs were clear and cardiac sounds revealed a grade III/VI pansystolic blowing murmur at the apex radiating to the axilla with a laterally displaced apex. There were no heaves or thrills. The jugular venous pulse was noted at 2 cm above the sternal angle, at 30°. Abdominal examination revealed no hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. No peripheral stigmata of embolic phenomena were identified in the extremities, skin or retina. The neurological examination was unremarkable.

Blood work revealed a hemoglobin level of 126 g/L, a white blood cell count of 13.45×109/L, an absolute neutrophil count of 10.96×109/L and a platelet count of 243×109/L. Serum electrolytes and creatinine levels were normal, as were liver enzyme levels and coagulation profile. An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with a normal QRS interval. Chest radiography showed no cardiomegaly or pulmonary edema. Transesophageal echocardiography demonstrated two large mitral valve vegetations; the first identified was a multilobulated vegetation on the anterior leaflet 2.4 cm ×1.4 cm with perforation of the leaflet, and another vegetation measuring 1.7 cm ×1.0 cm was identified on the posterior leaflet. Doppler interrogation confirmed moderate to severe mitral regurgitation. No abscesses were identified. The other valves were otherwise normal on echocardiography. Two different sets of blood cultures grew A viridans, with sensitivities to ceftriaxone (0.25 μg/mL) and penicillin (0.03 μg/mL).

Surgery was performed six days after admission because of general deterioration, evidence of moderate to severe mitral regurgitation and fenestration of the anterior mitral valve leaflet. Blood-based cardio-plegia was administered for myocardial protection. Through a left atriotomy, direct visualization of the mitral valve revealed large vegetations on the anterior and posterior leaflets with marked anatomical destruction of the valve (Figure 1A). Closer examination showed marked distortion of the valve apparatus, with a fenestration of the anterior leaflet (Figure 1B and 1C). The annulus was preserved. Mitral valve replacement using a bioprosthetic valve was performed. Care was taken to preserve the papillary-annular continuity to maintain ventricular function by saving as much of the mitral subvalvular apparatus as possible. Both the surgery and the postoperative course were uneventful. On postoperative day 7, he was discharged home without complications. A six-week treatment of penicillin was provided via pump through an indwelling intravenous line. Repeat postoperative blood cultures were negative for any growth.

Figure 1).

A Intraoperative view of the mitral valve through a left atreiotomy. Vegetations (arrows are seen on the anterior and posterior valve leaflets). B Resected specimen. The anterior valve leaflet is perforated (arrow). Large vegetations are seen on the anterior valve leaflet and the Pi segment of the posterior leaflet. Note the intense inflammation and fibrotic reaction contributing to the distorsion of the valve apparatus. C Ventricular aspect of the resected mitral valve showing the perforation of the anterior leaflet (arrow)

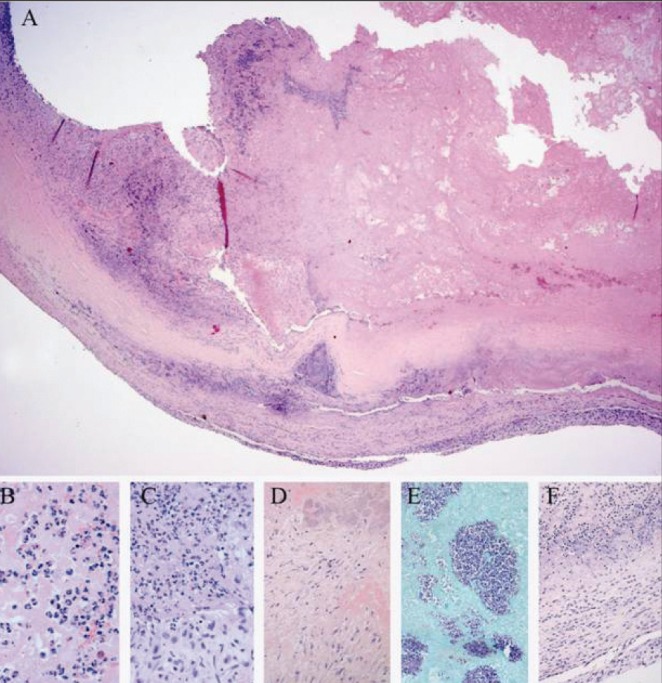

Gross pathological examination (Figure 1) of the mitral valve revealed a firm thrombus, 2.0 cm in its greatest dimension, attached to the ventricular aspect of a somewhat thickened valve. The thrombotic lesion appeared to have eroded into the valve, creating full-thickness valvular perforations measuring 1.0 cm and 0.7 cm in its greatest dimension (Figures 1B and 1C). Histological assessment of the valve revealed a prominent fibrinous exudate with neutrophils and tissue destruction, as well as areas of organization and fibrosis (Figures 2A to 2D). Furthermore, microscopy revealed a prominent population of Gram-positive cocci in clusters (Figure 2E), consistent with the A viridans found in the patient’s blood. Nectrotic debris and fibrotic destruction of the valve are shown in Figure 2F.

Figure 2).

Organizing mitral valve vegetation with bacterial growth and inflammatory infiltrate. A Hematoxylin and eosin stain of a representative section of the anterior mitral valve. Fibrotic remnant of the valve is seen at bottom of pictogram with fibrinous material on its ventricular surface. High magnification of A demonstrating focal infiltration by neutrophils (B), with areas of early-stage organization (C) and later-stage organization (D), as well as colonies of Gram-positive cocci in clusters (E; Gram-stain). High magnification of the valve (F) reveals necrotic debris and fibrotic destruction of the valve

DISCUSSION

We identified 10 previously reported cases of A viridans endocarditis (Table 1). In all reported cases, vegetations were identified on the mitral or aortic valves. One case resulted in congestive heart failure and death after discharge. In three cases, the isolated strain of A viridans was resistant to penicillin or quinolones. The laboratory findings were often nonspecific, with elevation in markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and a mild leukocytosis). Blood cultures and echocardiography provided the diagnosis in all instances reported.

As in the present case, the symptoms of endocarditis are often non-specific. From the onset of symptoms to first medical contact, a delay of at least five weeks was reported. This delay likely contributed to the destruction and perforation of the mitral valve leaflet.

CONCLUSION

A viridans endocarditis appears to be particularly virulent, despite its often long latency period (subacute 73% [eight of 11 cases] and acute 23% [three of 11 cases]) and comparably lower mortality rates (9% [one of 11 cases]) as opposed to left-sided, native valve Staphylococcus aureus infective endocarditis (30% to 40%). It nonetheless required a surgical approach in 45% (five of 11) of the cases reported. Given the aggressive nature of A viridans endocarditis and the variable time to diagnosis (a few days to seven months), prompt recognition of symptoms, blood cultures and echocardiography, including transesophageal echocardiography, should be performed when blood cultures are positive and suspicion index is high.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kerbaugh MA, Evans JB. Aerococcus viridans in the hospital environment. Appl Microbiol. 1968;16:519–23. doi: 10.1128/am.16.3.519-523.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebnöther C, Altwegg M, Gottschalk J, Seebach JD, Kronenberg A. Aerococcus urinae endocarditis: Case report and review of the literature. Infection. 2002;30:310–3. doi: 10.1007/s15010-002-3106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyazato A, Ohkusu K, Ishii S, et al. A case of infective Aerococcus urinae endocarditis successfully treated by aortic valve replacement. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 2011;85:678–81. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi.85.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alozie A, Yerebakan C, Westphal B, Steinhoff G, Podbielski A. Culture-negative infective endocarditis of the aortic valve due to Aerococcus urinae: A rare aetiology. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21:231–3. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Jong MF, Soetekouw R, Ten Kate RW, Veenendaal D. Aerococcus urinae: Severe and fatal bloodstream infections and endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3445–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00835-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho E, Coveliers J, Amsel BJ, et al. A case of endocarditis due to Aerococcus urinae. J Heart Valve Dis. 2010;19:264–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruegger D, Beiras-Fernandez A, Weis F, Weis M, Kur F. Extracorporeal support in a patient with cardiogenic shock due to Aerococcus urinae endocarditis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2009;18:418–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allegre S, Miendje Deyi VY, Beyer I, Pepersack T, Cherifi S. Aerococcus urinae endocarditis: First case report in Belgium and review of the literature. Rev Med Brux. 2008;29:568–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kass M, Toye B, Veinot JP. Fatal infective endocarditis due to Aerococcus urinae – case report and review of literature. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2008;17:410–2. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slany M, Freiberger T, Pavlik P, Cerny J. Culture-negative infective endocarditis caused by Aerococcus urinae. J Heart Valve Dis. 2007;16:203–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tekin A, Tekin G, Turunç T, Demiroğlu Z, Kizilkiliç O. Infective endocarditis and spondylodiscitis in a patient due to Aerococcus urinae: First report. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:402–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Q, Kwoh C, Attorri S, Clarridge JE., III Aerococcus urinae in urinary tract infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1703–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1703-1705.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grude N, Tveten Y. Aerococcus urinae and urinary tract infection. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2002;122:174–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuur PM, Sabbe L, van der Wouw AJ, Montagne GJ, Buiting AG. Three cases of serious infection caused by Aerococcus urinae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:368–71. doi: 10.1007/pl00015022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuur PM, Kasteren ME, Sabbe L, Vos MC, Janssens MM, Buiting AG. Urinary tract infections with Aerococcus urinae in the south of The Netherlands. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:871–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01700552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heilesen AM. Septicaemia due to Aerococcus urinae. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26:759–60. doi: 10.3109/00365549409008648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astudillo L, Sailler L, Porte L, Lefevre JC, Massip P, Arlet-Suau E. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae: A first report. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:890–1. doi: 10.1080/00365540310016664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos R, Santos E, Gonçalves S, et al. Lymphadenitis caused by Aerococcus urinae infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:353–4. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000027001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Remacha Esteras MA, Esteban Martín A, Parra Parra I, Remacha Esteras T. Urinary infection by Aerococcus urinae. Aten Primaria. 2003;31:553–4. doi: 10.1016/S0212-6567(03)70732-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imran M, Livesley P, Bell G, Pai P, Anijeet H. A case report of successful management of Aerococcus urinae peritonitis in a patient on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30:661–2. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2010.00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serefhanoglu K, Turan H, Dogan R, Gullu H, Arslan H. A case of Aerococcus urinae septicemia: An unusual presentation and severe disease course. Chin Med J (Engl) 2005;118:1318–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray TS, Muldrew KL, Finkelstein R, Hampton L, Edberg SC, Cappello M. Acute pyelonephritis caused by Aerococcus urinae in a 12-year-old boy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:760–2. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318170af46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colakoglu S, Turunc T, Taskoparan M, et al. Three cases of serious infection caused by Aerococcus urinae: A patient with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and two patients with bacteremia. Infection. 2008;36:288–90. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-7223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naghibi M, Javaid MM, Holt SG. Case study: Aerococcus urinae as pathogen in peritoneal dialysis peritonitis – a first report. Perit Dial Int. 2007;27:715–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sturm PD, Van Eijk J, Veltman S, Meuleman E, Schülin T. Urosepsis with Actinobaculum schaalii and Aerococcus urinae. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:652–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.652-654.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibler K, Truberg Jensen K, Ostergaard C, et al. Six cases of Aerococcus sanguinicola infection: Clinical relevance and bacterial identification. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40:761–5. doi: 10.1080/00365540802078059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gopalachar A, Akins RL, Davis WR, Siddiqui AA. Urinary tract infection caused by Aerococcus viridans, a case report. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:CS73–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leite A, Vinhas-Da-Silva A, Felício L, Vilarinho AC, Ferreira G. Aerococcus viridans urinary tract infection in a pediatric patient with secondary pseudohypoaldosteronism. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2010;42:269–70. doi: 10.1590/S0325-75412010000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tekin Koruk S, Bayraktar M, Ozgönül A, Tümer S. Post-operative bacteremia caused by multidrug-resistant Aerococcus viridans in a patient with gall bladder cancer. Mikrobiyol Bul. 2010;44:123–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nasoodi A, Ali AG, Gray WJ, Hedderwick SA. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus viridans. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:532–3. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor PW, Trueblood MC. Septic arthritis due to Aerococcus viridans. J Rheumatol. 1985;12:1004–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nathavitharana KA, Arseculeratne SN, Aponso HA, Vijeratnam R, Jayasena L, Navaratnam C. Acute meningitis in early childhood caused by Aerococcus viridans. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286:1248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6373.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kern W, Vanek E. Aerococcus bacteremia associated with granulocytopenia. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987;6:670–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02013068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JW, Grossman O. Aerococcus viridans infection. Case report and review. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1990;29:525–6. doi: 10.1177/000992289002900908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hyeong Park J, Kim YS, Kim MN, Kim JJ. Superior vena cava syndrome caused by Aerococcus viridans para-aortic abscess after heart transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:1475–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211270-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uh Y, Son JS, Jang IH, Yoon KJ, Hong SK. Penicillin-resistant Aerococcus viridans bacteremia associated with granulocytopenia. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:113–5. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swanson H, Cutts E, Lepow M. Penicillin-resistant Aerococcus viridans bacteremia in a child receiving prophylaxis for sickle-cell disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:387–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calık AN, Velibey Y, Cağdaş M, Nurkalem Z. An unusual microorganism, Aerococcus viridans, causing endocarditis and aortic valvular obstruction due to a huge vegetation. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2011;39:317–9. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2011.01352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen LY, Yu WC, Huang SH, et al. Successful treatment of Aerococcus viridans endocarditis in a patient allergic to penicillin. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:158–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popescu GA, Benea E, Mitache E, Piper C, Horstkotte D. An unusual bacterium, Aerococcus viridans, and four cases of infective endocarditis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2005;14:317–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Augustine T, Thirunavukkarasu, Bhat BV, Bhatia BD. Aerococcus viridans endocarditis. Indian Pediatr. 1994;31:599–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janosek J, Eckert J, Hudac A. Aerococcus viridans as a causative agent of infectious endocarditis. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1980;24:92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Untereker WJ, Hanna BA. Endocarditis and osteomyelitis caused by Aerococcus viridans. Mt Sinai J Med. 1976;43:248–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pien FD, Wilson WR, Kunz K, Washington JA. Aerococcus viridans endocarditis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:47–8. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]