Abstract

Introduction: Aging is typically associated with impairing behavioral patterns that are frequently and inappropriately seen as normal. Circadian rhythm changes and depressive disorders have been increasingly proposed as the two main overlapping and interpenetrating changes that take place in older age. This study aims to review the state of the art on the subject concerning epidemiology, pathophysiological mechanism, clinical findings and relevance, as well as available treatment options. Materials and Methods: A nonsystematic review of all English language PubMed articles published between 1995 and December 2012 using the terms “circadian rhythms”, “mood disorders”, “depression”, “age”, “aging”, “elderly” and “sleep”. Discussion and conclusion: Sleep disorders, mainly insomnia, and depression have been demonstrated to be highly co-prevalent and mutually precipitating conditions in the elderly population. There is extensive research on the pathophysiological mechanisms through which age conditions circadian disruption, being the disruption of the Melatonin system one of the main changes. However, research linking clearly and unequivocally circadian disruption and mood disorders is still lacking. Nonetheless, there are consistently described molecular changes on shared genes and also several proposed pathophysiological models linking depression and sleep disruption, with clinical studies also suggesting a bi-directional relationship between these pathologies. In spite of this suggested relation, clinical evaluation of these conditions in elderly patients consistently reveals itself rather complicated due to the frequently co-existing co-morbidities, some of them having been demonstrated to alter sleep and mood patters. This is the case of strokes, forms of dementia such as Alzheimer and Parkinson, several neurodegenerative disorders, among others. Although there are to the present no specific treatment guidelines, available treatment options generally base themselves on the premise that depression and sleep disturbances share a bidirectional relationship and so, the adoption of measures that address specifically one of the conditions will reciprocally benefit the other. Treatment options range from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Chronotherapy, and Light therapy, to drugs such as Melatonin/Melatonin agonists, antidepressants and sedatives.

Keywords: Aging, circadian rhythms, depressive disorders, Alzheimer, Parkinson, sleep

Introduction

Aging is associated with a large variety of multi-organic changes that altogether produce characteristic behavioral patterns that are typically associated with old age and that are frequently and mistakenly viewed as a normal and predicable aspect of ageing [1]. Two of these main changes concern the circadian rhythms (mainly the sleep-wake cycle) and mood disorders (manifested mostly by depression).

In spite of still not being a perfectly clear subject, the existing evidence interconnecting circadian rhythms and ageing suggests that the preeminent features of these circadian changes are a phase-advancement of the sleep-wake cycle and reduced circadian amplitudes of hormone secretion and core temperature [2].

These changes in sleep are less commonly viewed as naturally occurring during ageing processes [1]. They can be secondary to other disorders, such as psychiatric diseases [3]. These alterations are of primordial importance to elderly individuals, as manifested in 80% of American adults over 50 years old in a recent survey [1].

Concerning mood changes, although disorders such as Major Depression are a significantly reported feature of ageing, other primary and secondary psychiatric disorders are likely so. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s are two of these disorders, whose role in the development of typical “old age behaviour” must be taken into account.

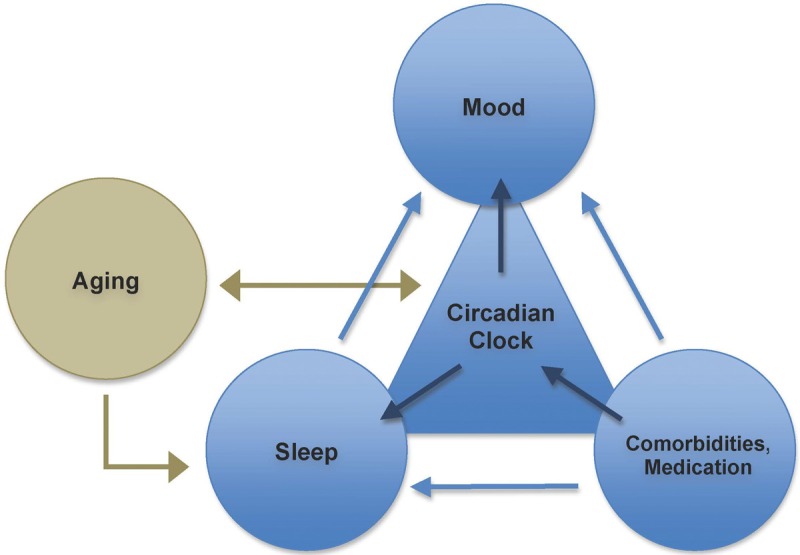

Reciprocally, mood and circadian rhythms have been shown to have a bidirectional relation and to share common features in epidemiology, clinical presentation, neurobiology and treatment implications [4-6]. A conceptual model was recently created by Foley [6], describing relationships between age, sleep, mood and comorbidities and polymedication (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Basic relationship Model of Mood disorders and Sleep (based on Foley et al [6] and in [7].

The sleep-wake cycle is only one of many centrally controlled circadian systems. The relationship between these different systems has been discussed in many articles, and it is suggested that many of them are regulated rather independently from the sleep-wake cycle, and thus are called sleep-independent mechanisms [7].

Age is associated with decreased electrical, hormonal and gene-expression activity of supra-chiasmatic nucleus (SCN) cells, which is thought to globally disrupt the body’s circadian activity. Reciprocally, circadian clock disruption has been shown to increase the ageing rate in mice.

Circadian clock malfunction has not only been shown to impair or modify sleep characteristics in animal models and humans, but also to be a contributory factor for mood disorders such as Major Depression, Bipolar Disorder, and Seasonal Affective Disorder. Its influence on sleep is thought to be the way through which circadian changes might influence memory formation and cognitive function, which are sleep-dependent processes. Conversely, sleep disruption is a known risk factor for Mood disorders, mainly Major Depression.

Co-morbidities such as neurodegenerative diseases (ex. Alzheimer’s) have been repeatedly shown to disrupt the circadian clock and these internal time changes are possibly one of the primordial signs of the disease. Moreover, directly or indirectly, they also determine mood or sleep changes. Other comorbidities include cerebrovascular diseases, renal disease, nocturia, respiratory disorders, gastrointestinal disease, chronic pain and arthritis, neurological diseases, menopause and cardiovascular disease.

Epidemiology

Among different psychiatric manifestations, depressive symptoms and Major Depressive Disorder are more prevalent in older adults (8-16% [8], and up to 4% [9,10], respectively) and in patients with dementia (up to 18% [11,12] in Alzheimer’s disease).

Circadian time-keeping abnormalities are characteristic of the ageing process. In fact, epidemiological studies have confirmed that more than 80% of adults with depression present with sleep changes [13], and that insomnia is the most common sleep complaint in older adults [4] and increases as a function of age [14].

Insomnia, defined as reported sleep difficulties by an individual, can be sub-classified as transient (lasting less than a week), acute (more than a week and less than one month) or chronic (>1 month of duration). The latter is the most clinically significant [5].

When asked about the presence of insomnia based on a vague definition - difficulty in falling asleep or staying asleep, or sleep that is non-restorative - between 60 [15,16] and 90% [17] of older adults complain of at least one of the referred symptoms. However, when considering a more strict definition, - chronic insomnia that causes distress or impairment - figures go down to approximately 12-20% [4]. Moreover, within those with insomnia at one point, 50-75% have persistent problems over the following 2 to 3 years [18,19].

Concerning the opposite spectrum in sleep disorders, 6 to 29% of depressed patients complain of hypersomnia [17] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Risk factors for Insomnia and Depression

| Insomnia | Depression |

|---|---|

| Age (#1 risk factor) [3] | |

| Gender | Gender |

| Socioeconomic status | Socioeconomic status |

| Chronic Comorbidities | Chronic Comorbidities (Stroke; Dementia; Alzheimer’s; Cerebrovascular disease; Coronary disease; Cancer) |

| Previous history of Insomnia | |

| Previous history of Depression [20,21] | |

| Depression [5,21,22] | Insomnia (A recent meta-analysis evidenced a two-fold risk [23], whereas other studies evidenced a bidirectional relationship [20,21]) |

| Substance Abuse [24] | Substance Abuse |

Epidemiology (brief note on gender-related differences)

Sex-related differences in sleep patterns in older subjects have also been noted. Although the detailed description of these is not the aim of the present study, there are some interesting facts on this matter: apparently, aged women show significantly longer rapid eye movement (REM) latencies [25] and increased REM sleep periods [26], whereas women in general complain more of sleep disorders than men [27,28], and insomnia was reported in 15% of women between 50 and 64 years old (25% is the prevalence in the age group ≥65 years).

Another interesting fact is that menopausal women have significant sleep disturbances that might be a consequence of menopause, or just coincidence [29].

Studies regarding menopausal women clusters have reported troubled sleep, deficient sleep quality, difficulty falling asleep, frequent awakenings at night and early morning wakefulness [29,30]. These complaints are associated with lower mood and depression.

A significant decrease of nocturnal melatonin secretion in women aged 48-60 years [31] has been noted, which has been suggested as the cause of deterioration in sleep maintenance in elderly women [32]. This has been documented [33].

Results of another study with the same number of male and female participants showed a gender-specific decline in melatonin secretion in women, but not in men. This highlights a certain relevance of gender differences when studying the relationship between melatonin and age-related disorders [32]. Since the prevalence of insomnia is almost twice as high in aged women rather than in men [27,28], it is possible that decreased circulating melatonin levels might play an important role in age-associated sleep disturbances in elderly women.

Vasomotor symptoms, reported in 68-85% of menopausal women and in 51-77% women with insomnia [29,34], have been shown to contribute to sleep disturbances. The hypothesis that melatonin might be a modulator of vascular tone, especially in cerebrovascular circulation, was raised with the identification of a specific melatonin receptor subtypes in vascular tissue [35]. Therefore, it is possible that lower estrogen and/or melatonin levels could modulate vascular reactivity and tone in menopausal women.

Mechanisms through which age causes circadian disruption

As mentioned above, age leads to important circadian rhythm changes [3] that are thought to manifest themselves as rather characteristic behaviour patterns.

Nonetheless, although some of these changes are presumably age-associated, others are thought to be especially prevalent in older adults not only due to age itself, but also due to comorbidities, which are especially prevalent in this age group [1,36]. This is the case of sleep wake cycle changes. In fact, when rigorous criteria for exclusion of comorbidities are applied in healthy older adults, the prevalence of insomnia is verified to be very low [37].

Studies on the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying the circadian rhythms disruption have yielded some interesting and rather consistent findings.

One of these disrupted mechanisms is the Melatonin system, in which five main changes have been noticed [38]. The first change refers to the consistent decrease of pineal function with age, in spite of age-related melatonin plasma level changes having shown high inter-individual variability. This can range from a relatively well-maintained circadian rhythm with only a light reduction of nocturnal levels, to abolished circadian rhythmicity with day and night time melatonin levels approximately equal. In individuals with maintained circadian rhythmicity, it has been noticed that there is a consistent phase-advance of the nocturnal plasma melatonin peak compared to young individuals. The second change concerns the light input pathway. In fact, with age there is an unconscious reduction in photoreception due to pupillary miosis and impaired crystalline lens light transmission (especially blue light) by melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells. This is thought to lead to sleep problems and contribute to the development of affective disorders. Moreover, recent studies have confirmed a decreased sensitivity in aged subjects to phase-delaying evening light [39]. The third change takes place in the central nervous system, and consists of impaired pineal innervation/interconnection between the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus and the Pineal gland, due to age or generalized central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction. This impaired connection can cause dysphased or flattened melatonin rhythms, therefore, decreased secretion [3]. Fourthly, localized Pineal Dysfunction (mainly pineal calcification) can reduce melatonin secretion by itself and can cause poor feedback on SCN [38]. Finally, SCN degeneration also takes place. The number of cells does not actually change, however, gene expression is dramatically changed [7].

Not only in the Melatonin system but also in other mechanisms other age-related changes occur that can disrupt the circadian system. These are: the degeneration of the peripheral oscillators (as opposed to a main degeneration of central circadian controllers (SCN)) - idiosyncratic peripheral circadian rhythm desynchronization theory [40]; presence of multiple chronic diseases (chronic pain, chronic inflammatory diseases such as arthritis), which are associated with a greater risk of developing sleep problems [1,6]; obesity and memory problems [6].

As many of the reported physiological changes seem to occur naturally with age, the effect of typical elderly co-morbidities has to be taken into account when considering circadian rhythms (mainly sleep) and social changes.

In fact, Alzheimer’s and other types of senility are associated with more [41] pronounced decreases in levels of melatonin than age-matched controls, with many of these patients showing completely abolished melatonin circadian rhythmicity. These changes are a result of tissue destruction in the SCN [38]. Age-related macular degeneration has been also associated with reduced melatonin secretion [38]. Cataracts may also decrease light exposure in the elderly [1]. Moreover, REM Sleep-Behaviour Disorder and Periodic Limb Movements during sleep, two conditions known to impair sleep quality, have been found to be significantly more prevalent in the elderly population [3].

Finally, light exposure theories have also been postulated when considering circadian changes. These state that elderly people expose themselves less frequently to bright environmental light (typically in the evening) and have an increased exposure to mid-morning light as a result of early awakenings [39]. Thus, there is a reduced exposure to light in the phase-delaying light-sensitive periods of the circadian cycle, contributing to a phase advance in the elderly [39].

Bi-directional mechanisms linking circadian disruption and mood disorders

Not only is age intrinsically related to circadian disruption, as circadian disruption itself is related to mood changes/disorders. This interrelationship is one of the most frequently observed difficulties when considering mood disorders in adults. A malfunction of the circadian system (ranging from changes in the melatoninergic system with secondary internal clock changes to primary circadian genetic/axonal paths alterations) can lead to neurobiological dysfunction, which in turn can manifest as depressive symptoms. Alternatively, mood destabilization can determine loss rhythmicity of the circadian system [13].

Linking mood regulation and circadian rhythms are some physiological and molecular mechanisms. One of these is the phase-shift hypothesis, in which mood disturbances are thought to result from phase advance or delay of central pacemakers and their regulated circadian rhythms of cortisol, temperature, melatonin and REM sleep as well as other circadian rhythms (mainly the sleep-wake cycle) [17]. Observations in depressed patients revealed that not only endocrine secretions with a typical circadian pattern (such as cortisol, TSH, norepinephrine, melatonin) lose their circadian pattern [13,17], but also the most evident circadian process of humans, sleep, also loses its circadian rhythmicity and structure (Table 2). In older subjects, the alteration of the rhythms of body temperature and of melatonin secretion have been reported to differ between sexes, with their amplitude reduced in older males, but not in older females [7].

Table 2.

| Aging | Depression |

|---|---|

| Decrease in amplitude/normality of circadian markers: | Decrease in amplitude of circadian markers: |

| - Core body temperature | - Core body temperature (lower diurnal, higher nocturnal) |

| - Melatonin | - Melatonin (decrease of nocturnal secretion and 24 h mean concentration) |

| - Cortisol | - Cortisol (global hypersecretion and peak-like secretion during sleep) |

| - TSH: higher diurnal, lower nocturnal | |

| - Noradrenaline (blunted circadian variations) | |

| Phase-advance of circadian markers | Phase advance of circadian markers (data refers to adults, who are not elderly) |

| Dysfunctional circadian rhythms (uncoupling from sleep-wake patterns) |

TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Another possible physiopathological explanation is the Internal Phase Coincidence Model. It considers that depression occurs when waking from sleep in a sensitive phase of the circadian period. This model has been superseded due to clinically observed incompatibilities. In fact, circadian distribution of REM sleep, secretion of cortisol and variation of core temperature across the circadian cycle have failed to demonstrate a consistent circadian rhythmicity, and thus, a solution of the mismatch between the circadian cycles has not been found [17].

A third possible explanation model is the Shortened REM Sleep Latency hypothesis. It is based on the observation that suppression of REM sleep (for example, observed with sleep deprivation) was associated with mood improvements. However, shortened REM latency is not specific for depression, neither is its’ suppression necessary for mood improvement. It is thought that sleep deprivation has antidepressant effects due to the enhancement of the process of sleep, which enhances slow-wave sleep that is reduced in depression. However, the normally prescribed and efficient antidepressants do not typically enhance slow-wave sleep [17].

Social Rhythms hypothesis, on its turn, states that vulnerable individuals exhibit more severe circadian disturbances with social rhythm disorganization. Improvement of social zeitgebers improves outcomes [17].

Also linking mood changes and circadian rhythmicity is the observation that many of the core symptoms of Major Depressive disorder demonstrate circadian rhythmicity, which is regulated by the molecular clock in the SCN. This especially concerns diurnal mood variation, which reaches its lower point in the morning in the majority of patients with unipolar major depression [13,17]. When compared to non-depressed patients, such variations appear to be related to inverted circadian rhythmicity activation of brain regions [17].

Moreover, some other observations yield additional hypothesis: the influence of light on humour is a possible contributing mechanism as overall lighting was demonstrated to be inversely correlated with depressed mood in older women [42]. On the other hand, sleep disturbance activates autonomic and inflammatory pathways, which in turn affect mood regulation and lead to depression [43,44].

Finally, based on the frequent association of sleep disturbances with mood disorders, chronobiological molecular studies have been carried out and revealed interesting data on the subject. In these, insomnia symptoms have been considered a predictor of depressive disorder [38]. These studies are supported by observations that changes in sleep architecture occur prior to the recurrence of a depressive episode [38]. In spite of such observations, the clear etiological relevance of circadian malfunction is only evident in specific subtypes of mood disorders, which have a clear poor coupling of circadian oscillators to external/internal rhythms. In fact, this is supported by observations that polymorphisms in core oscillator genes Per2, Cry2, Bmal1 (= Arntl) and Npas2 were associated with Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) [38]. Moreover, Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome was similarly associated with this disease [38]. Polymorphisms in melatoninergic GPR50 gene have also been associated with SAD [38].

In a similar fashion, polymorphisms in core oscillator genes Per3, Cry2, Bmal1 (= Arntl), Bmal2 (= Arntl2), Clock, Dbp, Tim, CsnK1ε and NR1D1 were found in Bipolar Disorder [38]. Polymorphisms in Clock gene were associated with chronicity of Bipolar Disorder [17]. Polymorphisms in melatoninergic RORB and GPR50 genes have also been associated with bipolar disease [38].

When considering Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), the association of this disease with circadian rhythmicity is not as clear as in Bipolar Disease or SAD. Existing studies point out that polymorphisms in circadian genes Cry1 and Npas2 are associated with MDD [38]. Besides, AANAT melatoninergic gene alterations have been associated with Major Depressive disorder and recurrent depression [38]. Clock gene polymorphisms have been associated with recurrent MDD [17]. On the other hand, other studies conclude that there is no secure evidence of the involvement of the circadian system in the etiopathogenicity of MDD, suggesting a faint photoperiodic hypothesis of depression [38].

Finally, circadian clock components have been found to regulate the activity of the enzyme IMAO-A, and consequently, mood [45].

Besides molecular ethiopathogenic models, Psychosocial and Iatrogenic hypotheses have also emerged. In fact, the first one considers that sleep issues lead to poor quality of life in older adults, thus, increasing the risk of late-life depression [8,43,44]. The latter, in its turn, states that older adults take multiple medications for their underlying chronic medical or psychiatric conditions that can disrupt sleep [1]. These medications include beta-blockers, bronchodilators, corticosteroids, diuretics, decongestants and many other cardiovascular, neurological, psychiatric and gastrointestinal medications (Table 2).

Existing evidence & clinical findings

Considering the many existing studies approaching the theoretical etiological hypothesis, some studies in clinical environment have similarly been carried out and yielded practical results.

Age typically involves important changes in sleep structure (Table 3) [46]. Current evidence suggests that these sleep changes are not due to a shortening of the circadian period with age, which has been found to be similar in both elderly and young subjects [39]. Instead, what is observed is that there is a general advance of the circadian rhythms; the sleep-wake cycle is the rhythm with the most pronounced advance relative to the others [39]. Having an estimated prevalence of 1-7% in older adults, this advance is commonly referred to as Advanced Sleep Phase Disorder (ASPD) and is characterized by sleep-wake times earlier than desired/conventional for at least one week [1]. One must note, however, that this sleep advance must not be understood as a general circadian rhythm advance, if normal physiological circadian rhythms such as body temperature have been observed in aged individuals [47,48]. This sleep cycle advance exposes the elderly to light in the early morning, which by itself potentiates this cycle by advancing the sleep-wake cycle even more [39].

Table 3.

Sleep changes in Ageing, Major Depression, and Elderly with Major Depression. Sources: [3,4,13,46,51]

| Ageing | Depression (typical) | Depressed Older patients [4] |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased total nocturnal sleep time | ? | |

| Delayed onset of sleep | Delayed onset of sleep | |

| Late Insomnia (Early to bed, early to rise - advanced circadian phase) | Terminal Insomnia (early morning awakening) | Terminal Insomnia (early morning awakening) - prominent feature |

| Decreased percentage of Stages 3 and 4 of NREM sleep (slow wave sleep or delta wave sleep) | Decreased percentage of slow wave sleep (Delta wave sleep - Stages 3 and 4 of NREM Sleep) | Decreased percentage of slow wave sleep (Delta wave sleep - Stages 3 and 4 of NREM Sleep) |

| Increased percentage of Stages 1 and 2 of NREM sleep | ||

| Increased percentage of Stage 1 NREM sleep | ||

| Decreased percentage of REM sleep | Increased phasic REM Density | |

| Decreased REM latency (proposed as a good non-specific biomarker of mood disorders) [17] | Decreased REM latency | |

| Reduced threshold for arousal from sleep (decline is progressive with age) | ? | |

| Fragmented sleep with multiple arousals | Fragmented sleep with multiple arousals | |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | Possible daytime napping |

NREM: Non-rapid eye movement.

Another prevalent circadian rhythm sleep disorder in older adults (especially in those with dementia) is Irregular Sleep-Wake Disorder (ISWD), which is characterized by the lack of a clearly identifiable circadian pattern of consolidated sleep and wake times [1]. Although there is a normal total amount of sleep, sleep itself is dispersed in 3 or more periods of variable length throughout the day. Erratic napping and fragmented night sleep are often prominent features of this disorder.

Depression is also associated with sleep changes (Table 3), being Insomnia the most frequent sleep disturbance in depressed patients [5,49]. Insomnia and depression have been related mainly in terms of the first raising risk for developing the second. A meta-analysis on longitudinal studies showed that non-depressed people with insomnia have a twofold risk of developing depression, when comparing to people with no sleep disturbances [50]. Moreover, the aging process doesn’t seem to influence the effect of insomnia in predicting subsequent depression [50]. However, recent studies showed that there is a bidirectional relationship in which each can predict the onset of the other [20,21]. Since aging and depression share common clinical presentations, it is rather difficult to distinguish what patterns are specific to each individual pathology, and what clinical picture emerges when both overlap (Table 3).

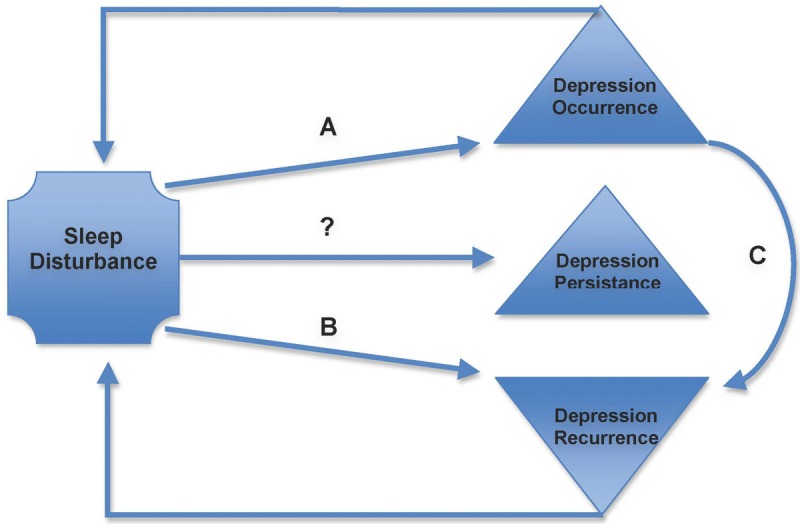

Sleep disturbances in Major Depression often linger and their presence can represent a residual phase of the depressive disorder [5,52]. Conversely, they can also present as a precursor of an inaugural major depressive disorder [53,54]. Moreover, these sleep issues have been shown to be independent risk factors in the recurrence of depression in older adults with a prior history of depression (Figure 2) [5].

Figure 2.

Existing evidence for the possible causal relation between sleep disturbances and Depressive disorders in Older Adults [4,5,13]. The figures evidences the established relationship between depression and sleep, based on broad age range studies, and not older people in particular (A) even after accounting for depression at baseline and in patients with previous history of depression; (B) in subjects with a prior history of depression, independently of other depressive symptoms, sociodemographic characteristics, chronic medical conditions and antidepressant medication use. (C) Predicting value proportional to degree of depression (stronger with major depression than with non-major).

From the rather low number of studies carried out in the area of the relationship between sleep disturbances and depression, there are few objective tools to measure sleep disturbances in depressive or non-depressive settings [49]. Indeed, most of them rely on self-reported sleep disturbances [54] as opposed to objectively measured sleep alterations, such as with polysomnography or actigraphy [49]. The only study that objectively measures sleep disturbances discloses the disappearance of the statistically significant association between depression and objective sleep disturbances after adjustment for multiple potential confounders (which did not occur in the case of self-reported sleep disturbances) [49]. Nonetheless, most studies evaluated sleep quality with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which has a sensitivity over 90% and a specificity over 85% [55].

In spite of such methodological differences, the inter-study results have revealed themselves to be rather concordant. In fact, sleep disturbances have been shown to be the strongest baseline predictors of depression recurrence in older patients with a history of depression, when compared to risk factors such as depressive symptoms, number and duration of the last depressive episodes, time since last depressive episode, antidepressant use, medical illness, age, gender, marital status and education. Indeed, sleep disturbance comprise a nearly 5-fold augmentation of risk of depression recurrence in older patients [5].

Other studies have found sleep disturbances predictive of depression in older subjects [54], and others have quantified sleep disturbance with a 57% risk of depression development in elderly subjects [56]. Conversely, depressive symptoms and Major Depressive Disorder have been given odds of 2 and 3.7, respectively, of concomitantly being associated with poor sleep quality in older men. Cross-sectional studies also highlighted a graded association between depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances (subjectively measured poor sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness, and objectively measured prolonged sleep latency) [49].

Daily life impact of depression and sleep disturbances

Both of these disorders have been independently shown to have deleterious effects on the quality of life of the elderly population: loss of sleep and depression in older subjects are both associated with an increased risk of accidents, falls, poor health and all-cause mortality [52,55-60]. Studies evaluating depression and sleep disturbances together found that the presence of sleep anomalies in a depressive context (history of prior depression) was associated with a decline in physical function and increased mortality in older adults [52]. Thus, there is an obvious decline in quality of life.

When considering the cognitive functions in the elderly, both sleep disturbance and depression are separately associated with neuropsychological deficits, even in healthy subjects [61]. Naismith et al [61] have studied sleep disturbance in older people with major depression, and hypothesized that late insomnia (versus early insomnia) might be independently and etiologically linked to poor neuropsychological performance, especially verbal fluency and memory. Thus, circadian disturbance is considered a possible biological marker for cognitive decline in older adults, either alone [3] or alongside depression [61] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical associations of different types of Insomnia in older patients with depression (based on [61])

| Early Insomnia | Late Insomnia |

|---|---|

| Depression severity | Depression severity |

| Poor global cognition | Later age of depression onset |

| Poor verbal fluency | |

| Poor memory |

In an iatrogenic perspective, impairment of sleep by psychotropic or sedative medication augments the risk of falls by approximately 28-fold. Cognitive impairment, in its turn, does the same by 5-fold [3].

Circadian rhythms and dementia

As seen above, the loss of synchronization between the multiple internal and external oscillators is associated with poor neurobehavioral performance, with the last one dependent on the correct function of the first [40]. Indeed, it has long been known that cognitive function is disturbed if there is a temporal misalignment between the sleep and clock-driven mechanisms, as demonstrated by studies concerning jet lag, shift work, or simply sleep deprivation [62,63]. Reciprocally, patients with dementia have been found to have disturbed sleep and circadian rhythms [64].

As age is associated with progressively dysfunctional circadian mechanisms, cognitive impairment has been being analyzed from a circadian consequential perspective. In fact, impairment of circadian activity rhythms has been found by Tranah et al [34] to be associated with an increased risk of developing dementia or Mild Cognitive Impairment in cognitively-healthy community-dwelling older women, independently of sleep efficiency and duration. The actigraphy findings of lower amplitude, less robust and time-delayed activity rhythms were consistently found to be associated with development of Dementia or Mild cognitive Impairment.

Circadian rhythms and neurodegenerative diseases

Not only does ageing of the circadian system result in further decline of mental performance, but it is also involved in specific age-associated neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease [65]. Clinical studies have revealed that even though each disease has its unique pathological signature, the disruption of sleep and circadian rhythms are common and early signs of them all. Abnormalities in the circadian clock and in sleep quality worsen as these diseases progress [65,66].

Melatonin activity has been also linked to these diseases, as oxidative radicals have been shown to have an important role in the their pathogenesis [67,68], and so Melatonin antioxidant activity is presumed to be helpful. This is particularly important in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, characterized by a high vulnerability of the central nervous system to oxidative attack and neoplastic disease [69].

Additionally, many pathways involved in neurodegeneration - such as metabolism, reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and oxidative stress response, DNA damage repair and, potentially, autophagy - are controlled by the circadian clock. Therefore, defects in circadian clock functions may have etiopathogenic roles in the diseases referred to above [7].

In spite of such potential pathogenic mechanisms, many questions remain unanswered. Further investigations can potentially direct the treatment of disorders of the ageing/neurodegenerative conditions, through the restoration of circadian clock functions [7].

Circadian rhythms and Alzheimer

This increasingly prevalent disease is being increasingly studied from a circadian perspective. Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease have been described as having radical sleep architectural alterations [70,71]. In fact, serious disruption in sleep-wake rhythmicity occurs soon after the onset of Alzheimer’s, and other findings such as decreased sleep efficiency, increased arousal and awakening frequency and a reduction in total sleep time can also be found [3]. Moreover, Alzheimer’s patients can also exhibit circadian disturbances such as reduced amplitudes and phase delay of circadian variation in core body temperature and activity [70,72-74]. As a consequence of such circadian changes, patients show increases in cognitive decline/dementia [34,75-77], number of daytime naps, nocturnal insomnia, wandering, disorientation and confusion [78].

Underlying these clinical manifestations are circadian clock changes, as already stated. In fact, the considerable impairment of the biological SCN clock in Alzheimer patients, resulting in lower vasopressin expression, might underlie the extremely disturbed sleep-wake rhythms that these patients often show [79,80]. Moreover, it has been observed that these subjects show a severe reduction in circulating melatonin levels [38,81-85] as well as considerable irregularity of its secretion [86], which are believed to be related to the severity of mental impairment [85].

Considering the stated melatonin anti-oxidant effects and its altered biorhythmicity, one might presume that it could be beneficial in Alzheimer’s patients [38]. Although there are positive results in experimental animal and in vitro models [87,88], no substantial benefits have been recorded in humans after a late onset of treatment [89], which is a relevant fact regarding human therapy, as Alzheimer’s is usually diagnosed relatively late in life. Accordingly, delay of the disease progression or life extension cannot be expected from melatonin treatment [38]. Still, it remains to be clarified whether new ionophore therapies might be successful, in which case melatonin could become a valuable adjunctive therapy to improve chronobiological and sleep parameters [38].

Even though some doubts remain concerning the benefits of melatonin treatment in preventing or delaying disease initiation and progression, there are some very well-documented beneficial effects regarding Alzheimer’s-associated sleep disorders, behavioral changes, and cognitive impairments [79,90-92]. This is particularly true for sundowning agitation, defined as the appearance or exacerbation of symptoms indicating confusion, increased arousal or impairment in the late afternoon, evening or at night, among elderly demented individuals [90,91,93-98]. Moreover, it reduces neurotoxicity of the ß-amyloid [99-101].

In spite of such results, it is clear that there are still many dissonant results, which may be due to high inter-individual variability among Alzheimer’s patients. The largest clinical trial [102] has not revealed statistically significant differences in objective measures of sleep after melatonin treatment [38].

Circadian rhythms and Parkinson

In this equally important neurodegenerative disease, between 60% and 90% of patients have sleep disturbances, which are correlated to increasing severity of the disease. The earliest and more commonly reported manifestations are difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep [3]. Other abnormalities are fragmented sleep with an increased number of arousals and awakenings and Parkinson-specific motor phenomena such as nocturnal immobility, rest tremor, eye blinking and dyskinesias [103-106]. Additionally, Parkinson patients have been reported to experience significant excessive daytime somnolence [3,107].

Sleep fragmentation in Parkinson Disease may be due to increased skeletal muscle activity, disturbed breathing, and REM-to-NREM variations of the dopaminergic receptor sensitivity [104]. The presupposed underlying mechanisms of these sleep disruptions might be an alteration of dopaminergic, noradrenergic, serotoninergic and cholinergic neurons in brainstem [108]. Rapid eye-movement behaviour disorder (RBD) is very common in Parkinson patients [109-112] and may also precede the onset of Parkinson’s. Patients with Parkinson Disease who have posture reflex abnormalities and autonomic impairment are at an increased risk for sleep-related breathing disorders [105]. In fact, these patients have circadian rhythm abnormalities that might be related to mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic abnormalities and mesostriatal system abnormalities [104]. Abnormalities of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmentum area often lead to EEG desynchronization and abnormal sleep-wake schedule disorder [108]. Additional attempts to explain the sleep-wake disruption in Parkinson’s Disease have been linked to reduction in serotonergic neurons of the dorsal raphe, noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus, and cholinergic neurons of the pedunculopontine nucleus [104]. Moreover, deterioration of dopamine-containing neurons caused by auto-oxidation due to exposure to high levels of free radicals might be reduced by melatonin [113,114].

Compared to Alzheimer’s, there are more doubts in this disease regarding the usefulness of melatonin. The fact that investigation has been mainly focused on the later stages of the disease (nigrostriatal degeneration), the earlier and etiologic mechanisms have been somehow neglected, which has limited knowledge development and therapeutic options on this matter [115-117].

Although some investigators regard the disease as being based on a melatonin-dopamine imbalance (a “melatonin hyperplasia” disorder) and have reported that melatonin antagonists would be beneficial [118,119], such conclusions are not in agreement with the findings of reduced MT1 and MT2 expression in the striatum and other brain regions such as the amygdala [120], nor with the observation of non-enhanced or decreased melatonin secretion [121-123]. Nevertheless, findings of the beneficial effects of melatonin antagonist raise doubts concerning treatment with melatonin or its agonists [118].

Despite all these reservations, melatonin and its synthetic agonists have been considered for treatment of Parkinson’s associated sleep disorders and depressive symptoms [122], with modest improvements of sleep having been demonstrated [38].

Treatment/prevention options

Prevention

Available literature yields scarce guidelines on this subject. Nonetheless, Hyong et al [5] proposed a simple two step strategy to identify older adults at risk for depression relapse and recurrence: 1- History of depression is an established risk factor for late-life depression 2- Among older subjects with a prior depression history, self-administration of PSQI could reveal the presence of sleep disturbances, a modifiable risk factor for depression recurrence [124,125].

Treatment

Given the bidirectional relationship between circadian rhythm disruption and mood disorders, a possible approach to treating both pathologies consists in the adoption of measures that address the frequently manifested sleep disturbances present in old people. In fact, given that poor sleep is a risk factor for depression development, improving sleep quality will possibly improve the quality of life of depressed older adults [6,17]. Reciprocally, therapies that address depression might have a directly beneficial impact on sleep complaints [17]. Thus, although treatments may be categorized as sleep- or depression-directed, one must understand the two approaches as interdependent and mutually empowering.

Although no specific treatment guidelines exist for sleep management in the elderly population with sleep disorders, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine has published proposed guidelines, especially for the advanced sleep changes observed in the context of old age [126]. Moreover, Bloom et al [1] have published an evidence- and expert-based approach for sleep disorder in the older population.

The available sleep-directed treatments discussed here are the conventional treatment options (sleep hygiene recommendations and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), Chronotherapy, Melatonin and Melatonin receptor agonists, and light therapy.

The first treatment option, sleep hygiene recommendations and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, has been ambiguously recommended in the context of Age associated ASPD. Some authors consider it not generally useful. Some say that avoiding long evening naps may help to consolidate nocturnal sleep [126], whereas others advise that they are beneficial [1]. Nonetheless, in a non-ASPD context, there is reported efficacy of behavioral therapy and sleep hygiene [127], although little published evidence with an elderly population basis is available. Conventional treatments are recommended for management of insomnia in older patients, and also for Irregular Sleep-Wake Disorder in the elderly [1]. Social Rhythm Therapy in a behavioral approach that targets normalization of circadian rhythmicity. Although only validated for the use in bipolar patients, some of its principles might be transposed in a tailored fashion for unipolar depression patients. However, more studies are necessary for such validation [17].

A second (but not secondary) treatment option is Chronotherapy, the therapeutic use of alterations in an individual’s sleep-wake schedule. When based on 3-hour sleep advances every 2 days it has been deemed efficient and with a 5-month long maintainable efficiency, although it is not practical and very disruptive [1,126]. Conversely, sleep delay, a more feasible option, can be prescribed to achieve the desired sleep period. An option is the delay of 1 to 3 hours every 2 days [40]. Sleep-restriction-sleep-compression, a therapy based on limiting time in bed to consolidate actual time sleeping, has been recommended by a panel of experts for the management of chronic insomnia in older people [1].

Chronotherapy has been reported by Naismith et al [61] to have beneficial effects in older sleep-disturbed patients with depressive disorder, as it can reverse neuropsychological dysfunction.

Thirdly, Melatonin has been proposed as a sleep-inducing/hypnotic drug in the aged population [95]. However, no data or guidelines seem to exist for its use in the context of depression with associated sleep disorders. Early morning Melatonin administration along with minimization of morning light exposure is recommended, although there is no evidence of its efficacy [126]. Administration of melatonin (3 mg p.o.) for up to 6 months in insomnia patients concomitantly with hypnotic treatment (benzodiazepine) has been shown to increase sleep quality and length, and decrease sleep latency and the number of wakeful episodes in elderly women with insomnia, as well as significant improvement of next-day function. Exogenous melatonin did not affect circulating levels of PRL, FSH, TSH or estradiol, nor were there any indications of hematological or blood biochemistry alterations in these women. This benzodiazepine potentiation effect of melatonin had been demonstrated in a previous study.

Moreover, melatonin can facilitate discontinuation of benzodiazepine therapy while maintaining satisfactory sleep quality. Some other studies showed a complete discontinuation of benzodiazepine treatment in patients taking them together with melatonin, whereas in other patients, the benzodiazepine dose could be reduced to 25-66% of the initial dose.

In a study of patients >65 years with major depressive disorder and sleep disturbances, it was noted that slow-release melatonin was more effective than a placebo in improving patients’ sleep. On subjective measures, caregiver ratings of sleep quality showed significant improvement in the 2.5-mg sustained-release melatonin group compared with the placebo in Alzheimer’s patients [95].

In the context of Irregular Sleep-Wake Disorder, Melatonin has shown inconsistent and inconclusive results [1].

Another available treatment is Melatonin Receptor agonists, which have been receiving increasing attention. Agomelatine, a recent anti-depressant with a novel mechanism of action (agonism of MT-1 and MT-2 receptors, and antagonism of 5-HT2c receptors) is conceptually very useful when there is a context of depressive disease associated with circadian disruption of sleep. It has shown very promising results in the young and middle-aged adult population, however, there is still very limited clinical trial information concerning the elderly population. In fact, some have verified no effect of Agomelatine in sleep variables other than phase shifts of cortisol, temperature and TSH profiles [128]. Others have shown its efficacy and excellent tolerability profile in older adults [129]. In fact, a recent non-interventional study [130] has confirmed the anti-depressant and daytime functioning (circadian rhythm) improvement effects of Agomelatine.

A recent randomized and double blind clinical trial reaffirmed the efficacy of Agomelatine (25-50 mg for 8 weeks) in the elderly population with moderate or severe MDD, also with minimal reported side effects [131].

In spite of such results, more interventional trials in this specific age group will be necessary to ascertain Agomelatine usefulness, not only in depressive and sleep disturbance settings, but also in short-period general circadian misalignment, as proposed by R. Leprout et al [128].

Last (but not least) is light therapy. Bearing in mind that in the elderly the circadian pacemaker remains responsive to light, bright light is proposed to manage age-derived circadian phase disturbances and related sleep disorders. Blue light is supported by many studies for the treatment of advanced sleep-wake cycles (for example, in the context of ASPD) in elderly subjects, although admittedly with more modest effects than in young people [126]. In ASPD of Ageing, light is expected to correct the underlying phase advance of the circadian clock, but not to alleviate early morning insomnia due to defective sleep drive homeostatic mechanisms [126]. Bright light (2500 to 10000 lux) should be administered for 1-2 hours in the evening (between 7:00 pm and 9:00 pm), the circadian delaying portion of the light phase response curve [1]. Conversely, in Irregular Sleep-Wake disorder of the elderly, light exporsure should be sought throughout the day except in the evening. Morning bright light (2500-5000 lux) for 2 hours during 4 weeks was found beneficial in subjects with dementia and ISWD [1].

A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial in elderly patients with MDD receiving no other concomitant treatment [41] revealed that 7500 Lux for 1 hour during the early morning every day for 3 weeks improved mood, sleep efficiency and melatonin circadian secretion amplitude in a fashion comparable to antidepressants. It also yielded continuing mood improvement and attenuation of cortisol hypersecretion after discontinuation of treatment.

Conversely, addressing depression in older adults might reciprocally improve sleep quality. In many cases there may be no need for specific sleep therapies if depression is addressed successfully [4]. Some strategies include: (1) Standard anti-depressant agents and psychotherapy: have been reported to improve sleep (references of studies involving old people); (2) Sedating antidepressants: Nefazodone, Mirtazapine or sedating tricyclic antidepressants might be both useful and dangerous. (3) Standard antidepressant and benzodiazepine receptor agonist: this concomitant treatment does not delay the anti-depressant response and may facilitate adherence in older adults [4]. Selection of short-action benzodiazepines (such as zolpidem and zaleplom) is usually more appropriate in older patients [4]. (4) Standard antidepressant and Trazodone, although with a less studied profile in the elderly population, may be beneficial. A low dose of trazodone as well as a standard antidepressant has been reported to be beneficial in the treatment of insomnia [127]; (5) Agomelatine: referred to above; (6) Chronotherapies: light therapy in seasonal and non-seasonal depression has shown moderate effects when directly addressing the treatment of these disorders. It can be used as an adjuvant to other therapies or alone (during pregnancy, intolerance to prescription pharmaceuticals, drug-resistant depression). It can also be combined with melatonin if carefully titrated [17].

Concerning specific interventions tested in the context of depression and old age, interventions that target sleep disturbances, mainly insomnia, have the potential to prevent depression recurrence and relapse in older adults [5]. In fact, sleep disturbances are a potentially modifiable risk factor [56]. In spite of having documented beneficial effects on sleep, antidepressant medication has been shown not to be protective considering the risk of sleep disturbance on depression recurrence [5]. Hypnotic medication usage in older adults is particularly risky, entailing increased risk of falls and cognitive impairment. Besides, some studies document its inefficiency in preventing depression recurrence and improvement of sleep quality in older adults [5].

On the other hand, Non-pharmacological behavioral interventions are a secure treatment for insomnia in older adults and have been shown to be effective. Cognitive behavioral therapy [58,125,132,133] and Tai Chi have been found to improve sleep quality in older adults [124].

Finally, physical exercise, based on the hypothesis of idiosyncratic peripheral circadian rhythm desynchronization, has been proposed as a potential resynchronizing activity in older adults [40]. This beneficial effect of exercise on circadian rhythms in older adults has been restated by many other studies [132,133], although recommendations are merely evidence-based [1]. In fact, older adults undertaking prolonged exercise regimens report fewer sleep problems.

Prognosis

Few studies with an elderly population approach prognosis in these patients. Therefore, it is mostly inferred based on non-elderly-based-studies.

It is known that poor sleep leads one to predict a poor response to non-pharmacological treatments of depression and it is also associated with increased risk of suicide. Conversely, better sleep quality post-treatment is associated with lower recurrence [17].

Concerning polysomnographic findings, the persistence of REM sleep abnormalities is associated with a lack of response to depression treatment and recurrence of depression. The same statement is valid for post-psychotherapy treatment for depression [17].

Conclusion

Although there are many studies independently addressing old age chronobiology, mood disorders and circadian rhythms, in laboratory, hospital or community settings, literature concerning both old age and mood disorders is rather sparse, so further research needs to be undertaken in this field.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Servier Portugal, Especialidades Farmacêuticas Lda, grant to L. Fernandes.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bloom HG, Ahmed I, Alessi CA, Ancoli-Israel S, Buysse DJ, Kryger MH, Phillips BA, Thorpy MJ, Vitiello MV, Zee PC. Evidence-based recommendations for the assessment and management of sleep disorders in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:761–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendlewicz J, Frank E, Hajak G, Lam RW, Popp R, Swartz HA, Turek FW. Current understanding and new therapeutic perspectives. France: Wolters Kluwer Health France; 2008. Circadian Rythms and Depression. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowley K. Sleep and sleep disorders in older adults. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21:41–53. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buysse DJ. Insomnia, depression, and aging: Assessing sleep and mood interactions in older adults. Geriatrics. 2004;59:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyong JC, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: A prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1543–1550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, Walsh J. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: Results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondratova AA, Kondratov RV. The circadian clock and pathology of the ageing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:325–335. doi: 10.1038/nrn3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995;18:425–432. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005;365:1961–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinberg M, Sheppard JM, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Steffens DC, Breitner JC, Lyketsos CG. The incidence of mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: the cache county study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15:340–345. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns A, Jacoby R, Luthert P, Levy R. Cause of death in Alzheimer’s disease. Age Ageing. 1990;19:341–344. doi: 10.1093/ageing/19.5.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohagen F, Rink K, Kappler C, Schramm E, Riemann D, Weyerer S, Berger M. Prevalence and treatment of insomnia in general practice. A longitudinal study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1993;242:329–336. doi: 10.1007/BF02190245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendlewicz J. Circadian Rhythm Disturbances in Depression. France: Wolters Kluwer Health France; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, Walsh J. National Sleep Foundation: Sleep in America Poll: 2002. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodge R, Cline MG, Quan SF. The natural history of insomnia and its relationship to respiratory symptoms. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1797–1800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haponik EF, Frye AW, Richards B, Wymer A, Hinds A, Pearce K, McCall V, Konen J. Sleep history is neglected diagnostic information. Challenges for primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:759–761. doi: 10.1007/BF02598994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Germain A, Kupfer DJ. Circadian rhythm disturbances in depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:571–585. doi: 10.1002/hup.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganguli M, Reynolds CF, Gilby JE. Prevalence and persistence of sleep complaints in a rural older community sample: the MoVIES project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:778–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz DA, McHorney CA. Clinical correlates of insomnia in patients with chronic illness. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1099–1107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivertsen B, Salo P, Mykletun A, Hysing M, Pallesen S, Krokstad S, Nordhus IH, Overland S. The bidirectional association between depression and insomnia: the HUNT study. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:758–765. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182648619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansson-Frojmark M, Lindblom K. A bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression, and insomnia? A prospective study in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baglioni C, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Riemann D. Clinical implications of the causal relationship between insomnia and depression: how individually tailored treatment of sleeping difficulties could prevent the onset of depression. EPMA J. 2011;2:287–293. doi: 10.1007/s13167-011-0079-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canellas F, de Lecea L. [Relationships between sleep and addiction] . Adicciones. 2012;24:287–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohayon M. Epidemiological study on insomnia in the general population. Sleep. 1996;19:S7–15. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_3.s7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leger D, Guilleminault C, Dreyfus JP, Delahaye C, Paillard M. Prevalence of insomnia in a survey of 12,778 adults in France. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dzaja A, Arber S, Hislop J, Kerkhofs M, Kopp C, Pollmacher T, Polo-Kantola P, Skene DJ, Stenuit P, Tobler I, Porkka-Heiskanen T. Women’s sleep in health and disease. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:55–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kripke DF, Jean-Louis G, Elliott JA, Klauber MR, Rex KM, Tuunainen A, Langer RD. Ethnicity, sleep, mood, and illumination in postmenopausal women. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kos-Kudla B, Ostrowska Z, Marek B, Kajdaniuk D, Ciesielska-Kopacz N, Kudla M, Mazur B, Glogowska-Szelag J, Nasiek M. Circadian rhythm of melatonin in postmenopausal asthmatic women with hormone replacement therapy. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2002;23:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuunainen A, Kripke DF, Elliott JA, Assmus JD, Rex KM, Klauber MR, Langer RD. Depression and endogenous melatonin in postmenopausal women. J Affect Disord. 2002;69:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson WM, Falestiny M. Women and sleep. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 2000;7:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s1068-607x(00)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrod CG, Bendok BR, Hunt Batjer H. Interactions between melatonin and estrogen may regulate cerebrovascular function in women: clinical implications for the effective use of HRT during menopause and aging. Med Hypotheses. 2005;64:725–735. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vitiello MV, Moe KE, Prinz PN. Sleep complaints cosegregate with illness in older adults: clinical research informed by and informing epidemiological studies of sleep. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:555–559. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tranah GJ, Blackwell T, Stone KL, Ancoli-Israel S, Paudel ML, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Redline S, Hillier TA, Cummings SR, Yaffe K. Circadian activity rhythms and risk of incident dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older women. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:722–732. doi: 10.1002/ana.22468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hampp G, Ripperger JA, Houben T, Schmutz I, Blex C, Perreau-Lenz S, Brunk I, Spanagel R, Ahnert-Hilger G, Meijer JH, Albrecht U. Regulation of monoamine oxidase A by circadian-clock components implies clock influence on mood. Curr Biol. 2008;18:678–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep and its disorders in aging populations. Sleep Med. 2009;10:S7–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace-Guy GM, Kripke DF, Jean-Louis G, Langer RD, Elliott JA, Tuunainen A. Evening light exposure: implications for sleep and depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:738–739. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hardeland R. Melatonin in Aging and Disease -Multiple Consequences of Reduced Secretion, Options and Limits of Treatment. Aging Dis. 2012;3:194–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welsh DK, Ptácek LJ. Circadian rhythm dysregulation in the elderly: advanced sleep phase syndrome. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lustberg L, Reynolds CF. Depression and insomnia: questions of cause and effect. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:253–262. doi: 10.1053/smrv.1999.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lieverse R, Van Someren EJW, Nielen MMA, Uitdehaag BMJ, Smit JH, Hoogendijk WJG. Bright light treatment in elderly patients with nonseasonal major depressive disorder: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:61–70. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monk TH, Kupfer DJ. Circadian rhythms in healthy aging--effects downstream from the pacemaker. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:355–368. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munch M, Knoblauch V, Blatter K, Schroder C, Schnitzler C, Krauchi K, Wirz-Justice A, Cajochen C. Age-related attenuation of the evening circadian arousal signal in humans. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1307–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker MP. The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1156:168–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Irwin MR, Wang M, Campomayor CO, Collado-Hidalgo A, Cole S. Sleep deprivation and activation of morning levels of cellular and genomic markers of inflammation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1756–1762. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolkove N, Elkholy O, Baltzan M, Palayew M. Sleep and aging: 1. Sleep disorders commonly found in older people. CMAJ. 2007;176:1299–1304. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dew MA, Hoch CC, Buysse DJ, Monk TH, Begley AE, Houck PR, Hall M, Kupfer DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd. Healthy older adults’ sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:63–73. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000039756.23250.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loewenstein RJ, Weingartner H, Gillin JC, Kaye W, Ebert M, Mendelson WB. Disturbances of sleep and cognitive functioning in patients with dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 1982;3:371–377. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(82)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paudel ML, Taylor BC, Diem SJ, Stone KL, Ancoli-Israel S, Redline S, Ensrud KE Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study Group. Association between depressive symptoms and sleep men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1228–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, Lombardo C, Riemann D. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27:1255–1273. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Motivala SJ, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR. Impairments in health functioning and sleep quality in older adults with a history of depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1184–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Livingston G, Blizard B, Mann A. Does sleep disturbance predict depression in elderly people? A study in inner London. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43:445–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA, Strawbridge WJ. Sleep complaints and depression in an aging cohort: A prospective perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:81–88. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:737–740. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1147–1156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331:1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Irwin MR, Cole JC, Nicassio PM. Comparative meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for insomnia and their efficacy in middle-aged adults and in older adults 55+ years of age. Health Psychol. 2006;25:3–14. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, Bjorvatn B, Havik OE, Kvale G, Nielsen GH, Nordhus IH. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2851–2858. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.24.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naismith SL, Norrie L, Lewis SJ, Rogers NL, Scott EM, Hickie IB. Does sleep disturbance mediate neuropsychological functioning in older people with depression? J Affect Disord. 2009;116:139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ancoli-Israel S, Cooke JR. Prevalence and comorbidity of insomnia and effect on functioning in elderly populations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:S264–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reynolds CF, Hoch CC, Buysse DJ, Monk TH, Houck PR, Kupfer DJ. Symposium: Normal and abnormal REM sleep regulation: REM sleep in successful, usual, and pathological aging: the Pittsburgh experience 1980-1993. J Sleep Res. 1993;2:203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1993.tb00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Foley DJ, Monjan A, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Incidence and remission of insomnia among elderly adults: an epidemiologic study of 6,800 persons over three years. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S366–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wulff K, Gatti S, Wettstein JG, Foster RG. Sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in psychiatric and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:589–599. doi: 10.1038/nrn2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naismith SL, Lewis SJ, Rogers NL. Sleep-wake changes and cognition in neurodegenerative disease. Prog Brain Res. 2011;190:21–52. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53817-8.00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reiter RJ. Oxidative damage in the central nervous system: protection by melatonin. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:359–384. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith MA, Nunomura A, Zhu X, Takeda A, Perry G. Metabolic, metallic, and mitotic sources of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:413–420. doi: 10.1089/15230860050192198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karasek M. Melatonin, human aging, and age-related diseases. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1723–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCurry SM, Reynolds CF, Ancoli-Israel S, Teri L, Vitiello MV. Treatment of sleep disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:603–628. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2000.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vitiello MV, Bliwise DL, Prinz PN. Sleep in Alzheimer’s disease and the sundown syndrome. Neurology. 1992;42:83–93. discussion 93-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van Someren EJ, Hagebeuk EE, Lijzenga C, Scheltens P, de Rooij SE, Jonker C, Pot AM, Mirmiran M, Swaab DF. Circadian rest-activity rhythm disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:259–270. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Witting W, Kwa IH, Eikelenboom P, Mirmiran M, Swaab DF. Alterations in the circadian rest-activity rhythm in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 1990;27:563–572. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90523-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhatt MH, Podder N, Chokroverty S. Sleep and neurodegenerative diseases. Semin Neurol. 2005;25:39–51. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-867072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Gillin JC, Campbell SS, Hofstetter CR. Sleep in non-institutionalized Alzheimer’s disease patients. Aging (Milano) 1994;6:451–458. doi: 10.1007/BF03324277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Jones DW, Kripke DF, Martin J, Mason W, Pat-Horenczyk R, Fell R. Variations in circadian rhythms of activity, sleep, and light exposure related to dementia in nursing-home patients. Sleep. 1997;20:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moe KE, Vitiello MV, Larsen LH, Prinz PN. Symposium: Cognitive processes and sleep disturbances: Sleep/wake patterns in Alzheimer’s disease: relationships with cognition and function. J Sleep Res. 1995;4:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1995.tb00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pollak CP, Perlick D. Sleep problems and institutionalization of the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1991;4:204–210. doi: 10.1177/089198879100400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van Someren EJW. Circadian rhythms and sleep in human aging. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:233–43. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hofman MA. The human circadian clock and aging. Chronobiol Int. 2000;17:245–259. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu RY, Zhou JN, van Heerikhuize J, Hofman MA, Swaab DF. Decreased melatonin levels in postmortem cerebrospinal fluid in relation to aging, Alzheimer’s disease, and apolipoprotein E-epsilon4/4 genotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:323–327. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Uchida K, Okamoto N, Ohara K, Morita Y. Daily rhythm of serum melatonin in patients with dementia of the degenerate type. Brain Res. 1996;717:154–159. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ohashi Y, Okamoto N, Uchida K, Iyo M, Mori N, Morita Y. Daily rhythm of serum melatonin levels and effect of light exposure in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1646–1652. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ferrari E, Arcaini A, Gornati R, Pelanconi L, Cravello L, Fioravanti M, Solerte SB, Magri F. Pineal and pituitary-adrenocortical function in physiological aging and in senile dementia. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:1239–1250. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Magri F, Locatelli M, Balza G, Molla G, Cuzzoni G, Fioravanti M, Solerte SB, Ferrari E. Changes in endocrine circadian rhythms as markers of physiological and pathological brain aging. Chronobiol Int. 1997;14:385–396. doi: 10.3109/07420529709001459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mishima K, Tozawa T, Satoh K, Matsumoto Y, Hishikawa Y, Okawa M. Melatonin secretion rhythm disorders in patients with senile dementia of Alzheimer’s type with disturbed sleep-waking. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:417–421. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Feng Z, Chang Y, Cheng Y, Zhang BL, Qu ZW, Qin C, Zhang JT. Melatonin alleviates behavioral deficits associated with apoptosis and cholinergic system dysfunction in the APP 695 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Pineal Res. 2004;37:129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Matsubara E, Bryant-Thomas T, Pacheco Quinto J, Henry TL, Poeggeler B, Herbert D, Cruz-Sanchez F, Chyan YJ, Smith MA, Perry G, Shoji M, Abe K, Leone A, Grundke-Ikbal I, Wilson GL, Ghiso J, Williams C, Refolo LM, Pappolla MA, Chain DG, Neria E. Melatonin increases survival and inhibits oxidative and amyloid pathology in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1101–1108. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Quinn J, Kulhanek D, Nowlin J, Jones R, Pratico D, Rokach J, Stackman R. Chronic melatonin therapy fails to alter amyloid burden or oxidative damage in old Tg2576 mice: implications for clinical trials. Brain Res. 2005;1037:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brusco LI, Marquez M, Cardinali DP. Melatonin treatment stabilizes chronobiologic and cognitive symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2000;21:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cohen-Mansfield J, Garfinkel D, Lipson S. Melatonin for treatment of sundowning in elderly persons with dementia - a preliminary study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2000;31:65–76. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(00)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brusco LI, Marquez M, Cardinali DP. Monozygotic twins with Alzheimer’s disease treated with melatonin: Case report. J Pineal Res. 1998;25:260–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1998.tb00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cardinali DP, Brusco LI, Liberczuk C, Furio AM. The use of melatonin in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2002;23(Suppl 1):20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cardinali DP, Brusco LI, Perez Lloret S, Furio AM. Melatonin in sleep disorders and jet-lag. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2002;23(Suppl 1):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pandi-Perumal SR, Zisapel N, Srinivasan V, Cardinali DP. Melatonin and sleep in aging population. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:911–925. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Evans LK. Sundown syndrome in institutionalized elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rindlisbacher P, Hopkins RW. An investigation of the sundowning syndrome. Int J of Ger Psychiatry. 1992;7:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fainstein I, Bonetto AJ, Brusco LI, Cardinali DP. Effects of melatonin in elderly patients with sleep disturbance: A pilot study. Curr Ther Res. 1997;58:990–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pappolla MA, Sos M, Omar RA, Bick RJ, Hickson-Bick DL, Reiter RJ, Efthimiopoulos S, Robakis NK. Melatonin prevents death of neuroblastoma cells exposed to the Alzheimer amyloid peptide. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1683–1690. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01683.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pappolla MA, Chyan YJ, Poeggeler B, Frangione B, Wilson G, Ghiso J, Reiter RJ. An assessment of the antioxidant and the antiamyloidogenic properties of melatonin: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2000;107:203–231. doi: 10.1007/s007020050018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Daniels WM, van Rensburg SJ, van Zyl JM, Taljaard JJ. Melatonin prevents beta-amyloid-induced lipid peroxidation. J Pineal Res. 1998;24:78–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1998.tb00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Singer C, Tractenberg RE, Kaye J, Schafer K, Gamst A, Grundman M, Thomas R, Thal LJ. A multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of melatonin for sleep disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep. 2003;26:893–901. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Peralta CM, Frauscher B, Seppi K, Wolf E, Wenning GK, Hogl B, Poewe W. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:2076–2080. doi: 10.1002/mds.22694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]