Abstract

Background

Women infected by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have a higher risk of contracting cervical cancer. Recent guidelines recommend that all HIV-positive women should receive two Pap smears in the first year after their HIV diagnosis.

Methods

This was a population-based cohort study, and the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan was used to estimate the Pap smear screening rate for 1449 HIV-infected women aged 18 years and over from 2000 to 2010. A multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with HIV-infected women who had received Pap smears.

Results

Of 1449 women, 618 (43%) women received at least one Pap smear. Only 14.7% of the HIV-infected women received Pap smears within one year after being diagnosed with HIV. A logistic regression analysis showed that the factors associated with receiving at least one Pap smear after HIV diagnosis were increasing age (AOR 1.04, 95% CI 1.03–1.05), high monthly income (AOR 1.83, 95% CI 1.51–2.23), any history of antiretroviral therapy (AOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.38–2.29), retention in HIV care (AOR 1.36, 95% CI 1.04–1.77), a history of sexually transmitted diseases (AOR 1.96, 95% CI 1.50–2.56), and any history of treatment for opportunistic infections (AOR 2.46, 95% CI 1.91–3.16).

Conclusions

A great need exists to develop strategies for promoting receipt of Pap smear screening services that specifically target severely disadvantaged women with HIV, particularly younger, lower income women and those in an asymptomatic phase.

Introduction

There are an estimated 33.3 million people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) throughout the world, and 15.7 million (47%) of the infected are women.1 An estimated 1.68 million women are living with HIV/AIDS in Asia.2 However, according to the Taiwan Center for Disease Control (Taiwan CDC), HIV and AIDS diagnoses have been reported for relatively few women and female adolescents in Taiwan. Heterosexual men and men having sex with men have accounted for the vast majority of the HIV-infected population, and the male-female ratio was 20:1 before 2003. Between 2003 and 2007, Taiwan experienced an endemic outbreak of HIV among injecting drug users (IDUs), accounting for two-thirds (71%) of HIV cases reported in Taiwan during the years 2003–2007.3 Injection drug use became the most common mode of transmission among women newly infected with HIV during the outbreak, and the male-female ratio among people living with HIV fell from 20:1 to 7:1. After the implementation of a national harm reduction program in 2006 to combat the HIV outbreak among IDUs, the male-female ratio returned to 17:1 by 2010.3,4 In 2012, among 2224 cases of people newly diagnosed with HIV, the male-female ratio was 29:1 (2151 male and 73 female).4 At the end of 2012, it was found that 1707 (7.57%) of 22,532 people living with HIV were women, and 70% of them were of childbearing age (18–30 years old).4

Invasive cervical cancer was defined as an AIDS-related malignancy in 1993 and was the most common malignancy among women with HIV.5,6 Due to immunosuppression, HIV-infected women were not only 5-fold more likely to develop cervical dysplasia 7 but were also at a 2- to 12-fold increased risk for cervical cancer compared to HIV-negative women.8–11 In addition, HIV-infected women with invasive cervical cancer are more likely to present with advanced clinical disease, to have persistent or recurrent disease at follow-up, a shorter time to recurrence, and a shorter survival time after diagnosis, and are more likely to die of cervical cancer.12 Invasive cervical cancer is preventable through Papanicolaou (Pap) smear screening if detected at an early stage. The Pap smear has demonstrated similar sensitivity in detecting cervical cytologic abnormalities in both uninfected and HIV-infected women.13 Recent guidelines recommend that all HIV-positive women have a pelvic examination and a Pap test at the first clinical visit. Pap tests should be performed twice during the first year after the diagnosis of HIV infection and, following two initial normal Pap smears, should be performed annually thereafter.14

Nearly 1 in 4 women do not receive an annual Pap test in the United States. 15 In Taiwan, the national Pap smear screening program has provided yearly Pap smear screening for all women aged 30 years or older since 1995. However, only 50%–60% of the general population has undergone Pap smear screening in the past three years.16 Following the U.S. guidelines,14 in 2010, the Taiwan CDC recommended that all HIV-infected women receive two Pap smears in the first year after their HIV diagnosis, with annual screening thereafter for women with normal results on both tests.14,17 Despite these recommendations, limited information is available on longitudinal studies of the trend shown by the Pap smear screening rate and factors associated with recipients of Pap smears among HIV-infected women.

Despite the significance of regular Pap smear screening, no studies to date have evaluated the rate of HIV-infected women who undergo Pap smear screening during their first year after HIV diagnosis in Taiwan. In this study, we evaluated the trends in Pap smear screening rates using the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) and identified factors associated with recipients of Pap smears among HIV-infected women in Taiwan.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective population-based cohort study using outpatient clinic files retrieved from the NHIRD for the years 2000–2010.

Data sources

The Bureau of National Health Insurance (BNHI), Taiwan Department of Health, consolidated all of the health insurance systems into a universal NHIRD in 1995. As of 2007, the NHIRD covered approximately 99% of the 23 million people living in Taiwan and contracted with 99% of the hospitals and clinics on the island.18 The large sample size and high quality of Pap smear utilization claims data have ensured that this dataset provides a valuable opportunity to estimate the utilization of Pap smear services among both patients with disabilities19 and nurses.20 The claims data of ambulatory care facilities were used for analysis in this study, including the records of all outpatient departments of hospitals or clinics, personal identification number (PIN), date of birth, sex, insurance area, insurance monthly salary, date of medical visit, preventive health service utilization, prescriptions, and the three leading diagnoses of outpatients. The BNHI encrypted any identifying information of both the patients and medical facilities. This study was exempt from full review by the Institutional Review Board of National Cheng Kung University Hospital due to the de-identified secondary data analysis for research purposes.

Cohort of patients with HIV

To ensure the accuracy of the claims files, patients (n=19,028) who visited ambulatory care facilities with principal diagnoses of HIV infection (ICD-9-CM codes 042 or V08) were first selected, and 16,402 patients were confirmed using code 91, which refers to HIV cases reported for reimbursement paid by the Taiwan CDC. Tests of goodness of fit by age were used to assess consistency and showed no difference between the study cohort and HIV cases reported by the Taiwan CDC during 2000–2010 (χ2=6.66, p=0.25).4 This study cohort of HIV patients provides a valuable opportunity to estimate the Pap test rate among women living with HIV in Taiwan.

We excluded 14,829 (90.41%) patients who were male, 54 (0.33%) patients whose records had incomplete information on gender, and 37 (2.44%) women who were under the age of 18, had a history of cervical malignancy, or had undergone a total abdominal hysterectomy prior to the diagnosis of HIV infection. The final sample included 1449 women diagnosed with HIV between 2000 and 2010.

Study endpoints and potential confounders

Only Pap smears performed after the time of HIV diagnosis were counted. Information on the receipt of Pap smears was retrieved using examination codes (31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 55012C). Information on potential confounding factors was also retrieved from the claims data, including age at diagnosis of HIV infection, income-related insurance payment (as a proxy for monthly income), level of urbanization (according to the classification scheme proposed by Liu et al.)21, occupation (white-collar workers were defined as those working indoors for more than 12 hours per day, i.e., public servant, technician, and professional staff; other workers were recorded as blue collar), drug dependence (ICD-9: 304), use of antiretroviral therapy (using prescription codes),17 pregnancy history (prenatal service number IC41-60), retention in HIV care (referring to women completing at least two medical visits to HIV specialists at least 3 months apart in a calendar year),22 history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (ICD-9: 0541, 0781, 0788, 091–097, 098, 099, 131, 132), and treatment for opportunistic infections (OIs) after the diagnosis of HIV (ICD-9: 4829, 112, 3210, 0074, 0785, 054, 1369, 0088, 0312, 1179, 1363, 130, 010–018, 0030, 0539).17

Statistical analysis

The sociodemographic data, distributions of categorical age, occupation, urbanization level, monthly income, use of antiretroviral therapy, pregnancy history, retention in HIV care, history of STDs, and treatment for OIs were compared between women with Pap smear and those without using chi-square tests. The annual trend in Pap smear screening rates was calculated using the annual number of patients who had received a Pap smear as the numerator (deletion of duplicate cases) and the annual number of diagnosed HIV-infected women as the denominator (deletion of cases with an observation time of less than 1 year). Multivariate logistic regression models were used to determine the likelihood of HIV-infected women receiving Pap tests after adjusting for variables that were significantly related to the receipt of Pap smears after HIV diagnosis in the prior chi-square analyses. All analyses were performed with SPSS 17.0 and the SAS 9.2 statistical package.

Results

A total of 1449 women older than 18 years and with HIV infection were identified. Two-thirds of the women (76%, n=1,102) were diagnosed with HIV after 2004. The median length of observation time for the women in this cohort was 4.3 years (mean=4.8 years, SD=3.2 years). Of this group, 74.7% were diagnosed with HIV at ages 18–39 years (mean±SD, 34.5±10.9 years). Patients enrolled in this study were generally of low socioeconomic status; 83.1% were blue-collar workers, only 25.3% lived in highly urbanized areas, and 72.6% had low incomes. Of the 1449 women, 368 (25.4%) had a history of STDs; 446 (30.8%) had been treated for OIs after the diagnosis of HIV infection, and 107 (7.4%) had been diagnosed with cervical (uterine) dysplasia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Associations Between Associated Factors and Receipt of a Pap Smear, 2000–2010

| |

All subjects (n=1449) |

With Pap testsa (n=618, 43%) |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. (%) | No. | Row % | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Age (years) | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05)*** | ||||

| 18–29 | 623 (43.0) | 181 | 29.1 | Referent | |

| 30–39 | 459 (31.7) | 233 | 50.8 | 2.52 (1.95, 3.24)*** | |

| 40–49 | 222 (15.3) | 128 | 57.7 | 3.33 (2.42, 4.57)*** | |

| 50 or over | 145 (10.0) | 76 | 52.4 | 2.69 (1.86, 3.89)*** | |

| Drug dependence | |||||

| No | 1076 (74.3) | 485 | 45.1 | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 373 (25.7) | 133 | 35.7 | 0.68 (0.53, 0.86)** | 0.86 (0.65, 1.14) |

| Monthly income (NTD) | 1.83 (1.51, 2.23)*** | ||||

| ≦17,280 | 1052 (72.6) | 384 | 36.5 | Referent | |

| 17,281–26,400 | 258 (17.8) | 143 | 55.4 | 2.16 (1.64, 2.85)*** | |

| 26,401–43,899 | 87 (6.0) | 50 | 57.5 | 2.35 (1.51, 3.66)*** | |

| ≧43,900 | 52 (3.6) | 41 | 78.8 | 6.49 (3.29,12.76)*** | |

| Urbanization level | |||||

| 1 (most urbanized) | 366 (25.3) | 178 | 48.6 | 1.30 (0.99, 1.71) | 0.87 (0.63, 1.20) |

| 2 | 606 (41.8) | 239 | 39.4 | 0.89 (0.70, 1.14) | 0.86 (0.66, 1.13) |

| 3 (least urbanized) | 477 (32.9) | 201 | 42.1 | Referent | Referent |

| Occupation | |||||

| Blue collar | 1204 (83.1) | 490 | 40.7 | Referent | Referent |

| White collar | 245 (16.9) | 128 | 52.2 | 1.59 (1.21, 2.10)** | 1.0 (0.68, 1.47) |

| Use of antiretroviral therapy | |||||

| Never | 697 (48.1) | 222 | 31.9 | Referent | Referent |

| Ever | 752 (51.9) | 396 | 52.7 | 2.36 (1.92, 2.95)*** | 1.78 (1.38, 2.29)*** |

| Pregnancy history | |||||

| No | 1026 (70.8) | 457 | 44.5 | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 423 (29.2) | 161 | 38.1 | 0.77 (0.61, 0.97)* | 1.12 (0.86, 1.48) |

| Retention in HIV care | |||||

| No | 526(36.3) | 195 | 37.1 | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 923 (63.7) | 423 | 45.8 | 1.44 (1.15, 1.78)*** | 1.36 (1.04, 1.77)* |

| History of STDs (ICD-9) | |||||

| No | 1081 (74.6) | 395 | 36.5 | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 368 (25.4) | 223 | 60.6 | 2.67 (2.10, 3.41)*** | 1.96 (1.50, 2.56)*** |

| Treatment for OIs after HIV diagnosis (ICD-9) | |||||

| No | 1003 (69.2) | 343 | 34.2 | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 446 (30.8) | 275 | 61.7 | 3.09 (2.46, 3.90)*** | 2.46 (1.91, 3.16)*** |

Results from patients who had received Pap smears.

p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

NTD, New Taiwan Dollars; OR, odds ratio; STDs, sexually transmitted diseases; OIs, opportunistic infections.

The trend in the Pap smear screening rate

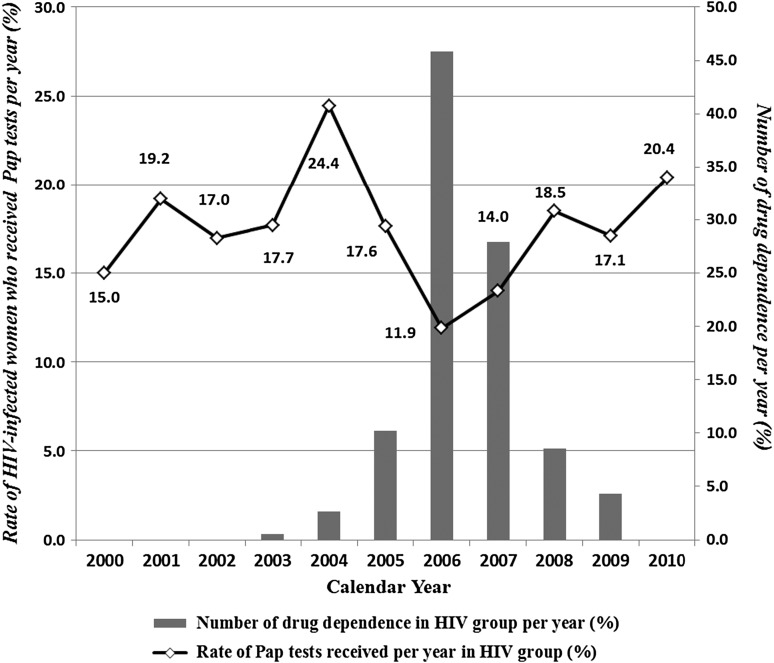

The trend in the Pap screening rate among HIV-infected women over the 11-year period is shown in (Figure 1). A total of 618 women (43%) had received one or more Pap smears during 2000–2010 (annual rates ranged from 11.9% to 24.4%). Only 14.7% (193/1311) of the women received Pap smear screening in the first year after their HIV diagnosis. The Pap smear rates were negatively correlated with the percentage of HIV-infected women with drug dependence (from 2004 to 2006, r=–0.029, p<0.001; from 2006 to 2008, r=–0.017, p<0.001) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Pap smear screening rates among HIV-infected women in Taiwan, 2000–2010. The sharp decrease in the screening rate from 2005 to 2006 was significantly associated with an increase in the number of women with drug dependence. The Pap smear rates and drug dependence indicate a negative linear trend (from 2004 to 2006, r=−0.029, p<0.001; from 2006 to 2008, r=−0.017, p<0.001).

Factors associated with receipt of a Pap smear

Univariate analyses showed that receipt of a Pap smear was significantly associated with age at diagnosis of HIV infection, drug dependence, monthly income, occupation, use of antiretroviral therapy, retention in HIV care, history of STDs, and treatment for OIs.We also evaluated factors associated with one versus more than one Pap smear and found that the receipt of ≥2 Pap smears was significantly associated with older age at diagnosis with HIV infection, no drug dependence, higher monthly income, and treatment for OIs (Table 2). A multivariate logistic regression revealed that receipt of a Pap smear was significantly associated with increasing age (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR]=1.04, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]=1.03, 1.05), high monthly income (AOR=1.83, 95% CI=1.51, 2.23), use of antiretroviral therapy (AOR=1.78, 95% CI=1.38, 2.29), retention in HIV care (AOR=1.36, 95% CI=1.04, 1.77), a history of STDs (AOR=1.96, 95% CI=1.50, 2.56) and treatment for OIs (AOR=2.46, 95% CI=1.91, 3.16) (Table 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of Women Who Underwent One Versus More Than One Pap Smear Among HIV-Infected Women (n=618)

| |

With Pap test once (n=181, 29.3%) |

More than once (n=437, 70.7%) |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | n | % | P value¶ |

| Age (years) | 0.007 | ||||

| 18–29 | 70 | 38.7 | 111 | 25.4 | |

| 30–39 | 63 | 34.8 | 170 | 38.9 | |

| 40–49 | 28 | 15.5 | 100 | 22.9 | |

| 50 or over | 20 | 11.0 | 56 | 12.8 | |

| Drug dependence | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 121 | 66.9 | 364 | 83.3 | |

| Yes | 60 | 33.1 | 73 | 16.7 | |

| Monthly income (NTD) | 0.02 | ||||

| ≤17,280 | 129 | 71.3 | 255 | 58.4 | |

| 17,281–26,400 | 34 | 18.8 | 109 | 24.9 | |

| 26,401–43,899 | 8 | 4.4 | 42 | 9.6 | |

| ≥43,900 | 10 | 5.5 | 31 | 7.1 | |

| Urbanization level | 0.66 | ||||

| 1 (most urbanized) | 54 | 29.8 | 124 | 28.4 | |

| 2 | 65 | 35.9 | 174 | 39.8 | |

| 3 (least urbanized) | 62 | 34.3 | 139 | 31.8 | |

| Occupation | 0.1 | ||||

| Blue collar | 151 | 63.4 | 339 | 77.6 | |

| White collar | 60 | 16.6 | 98 | 22.4 | |

| Use of antiretroviral therapy | 0.46 | ||||

| Never | 69 | 38.1 | 153 | 35.0 | |

| Ever | 112 | 61.9 | 284 | 65.0 | |

| Pregnancy history | 0.24 | ||||

| No | 128 | 70.7 | 329 | 75.3 | |

| Yes | 53 | 29.3 | 108 | 24.7 | |

| Retention in HIV care | 0.19 | ||||

| No | 64 | 35.4 | 131 | 30.0 | |

| Yes | 117 | 64.6 | 306 | 70.0 | |

| History of STDs (ICD-9) | 0.43 | ||||

| No | 120 | 66.3 | 275 | 62.9 | |

| Yes | 61 | 33.7 | 162 | 37.1 | |

| Treatment for OIs after diagnosis of HIV (ICD-9) | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 124 | 68.5 | 219 | 50.1 | |

| Yes | 57 | 31.5 | 218 | 49.9 | |

P values were calculated using chi-square for categorical variables.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use population-based claims data to report a longitudinal trend of annual Pap smear screening rates among HIV-infected women in Asia. Our study found that 43% of women living with HIV received one or more Pap smears over an average of 4.3 years of follow-up, which is lower than the 50%–60% of the general population in Taiwan16 and much lower than the 77% of HIV-infected women reported in the United States from 2002 to 2004,15 91% in Northern Italy from 2006 to 2007,23 and 77.9% in California from 2002 to 2006.24 The low Pap smear screening rate among HIV-infected women in Taiwan was consistent with a systematic review reporting that cervical cancer screening rates are consistently low among Asian women in both Asian and Western countries.25 Furthermore, our study showed that only 14.4% of women had a Pap smear in the first year after the diagnosis of HIV infection, which is much lower than the 83% in the United States,26 61% in Northern Italy,23 and 76.2% in the United Kingdom.27 In 2010, the Taiwan CDC recommended that all HIV-infected women should receive two Pap smears in the first year after HIV diagnosis. Our findings remained suboptimal with respect to the current recommendations for at least annual Pap smears for HIV-positive women. In addition to the cultural differences in barriers to cancer screening utilization (e.g., Taiwanese women typically have more gynecological ailments and are also more unlikely to undergo a Pap test),28 the lower Pap smear rate in HIV-infected women compared to the general population in Taiwan16 may be related to social stigma and stereotypes surrounding HIV/AIDS.29

The prevalence of Pap smear screening ranged from 11.9% to 24.4% during 2000–2010, with a sharp decrease to 6% from 2005 to 2006. One potential explanation was the negative association with Pap smear rates and the percent of female IDUs during the outbreak of HIV infection among IDUs during 2003–2007. Women who were diagnosed with drug dependence were associated with not having a Pap smear in a bivariate analysis. However, the multivariate analysis revealed that drug dependence was no longer significant after controlling for other variables. These findings contrast with those of previous studies indicating that current IDUs or women with substance abuse were associated with a decreased rate of adherence to both gynecological appointments and primary care visits.30,31 These differences may be related to our dataset in that relying on ICD9 codes to identify drug dependence is problematic because not all diagnoses are coded in clinical visits.

Increasing age was significantly associated with having at least one Pap smear after HIV diagnosis. This finding is in contrast to that of a previous report indicating that older individuals were less likely to receive a Pap test in Western countries.15,30,32 The differences may be related to the national Pap smear screening policy in Taiwan, which targets women aged 30 years and older. Socioeconomic status was associated with the receipt of a Pap smear, which is consistent with previous reports on the general population in Taiwan 33 and HIV-infected African-American women.34 For low-income HIV-infected women who are less likely to receive a Pap smear, ensuring they undergo the recommended Pap smear screening requires offering them additional rewards (e.g., coupons or bonuses) to increase their motivation.

Other notable associations with the receipt of a Pap smear were the diagnosis of OIs and STDs, use of antiretroviral therapy, and retention in HIV care. These findings contrast with previous literature reporting an association between a low CD4 count and failure to receive a Pap smear.15,24,31 Gynecological healthcare is an important component of ongoing HIV care in women. Feeling relatively healthy, asymptomatic HIV-infected women may think that gynecologic visits are not important, or they might spend less time discussing health problems with their infectious disease specialist.30 This finding simultaneously indicates that HIV-infected women typically have an AIDS-related syndrome or diagnosis with sexually transmitted disease that would require the attention of health providers.15

Cervical cancer poses a significant but preventable risk to women with advanced HIV illness. Our findings provide a baseline against which future analysis of Pap provision after the recommendations issued by the Taiwan CDC in 2010 can be compared. Integrating gynecological and reproductive care into primary HIV care is an important tool for increasing adherence to the recommended frequency of cervical cancer screening among HIV-infected women. It is important to regularly monitor provision of Pap smears for women with HIV annually; more studies are needed to further identify the barriers preventing HIV-infected women from receiving the Pap smear screenings after diagnosis.

Limitations

Some limitations of this study merit attention. First, the study reports only those patients who received a Pap smear in outpatient settings. However, the study uses an extensive nationwide population-based database, leaving little room for selection and nonresponse biases. Second, the study was limited by the nature of its retrospective design, which relies on existing data sources. Certain clinical factors, such as CD4 count, viral load, socioeconomic status, and social stigma, might lead some patients to decline healthcare. A third limitation of this retrospective study is the study's reliance on the ICD9 code for substance dependence. The NHIRD lacks detailed clinical information and other lifestyle-related, potentially confounding factors of analysis that might compromise our findings.

Conclusions

During this 11-year study period, HIV-infected women in Taiwan were observed to have low Pap smear screening rates. Only 14.7% of the HIV-infected women received Pap smears within one year after being diagnosed with HIV. It is crucial to integrate gynecologic and reproductive care into primary HIV care. To increase cervical cancer screening among HIV-infected women, healthcare providers should ensure that cervical cancer screening is performed twice in the year after diagnosis and annually thereafter, being particularly alert to ensure Pap tests for women of young age or low income and those in an asymptomatic phase.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants (NSC 100-2629-B-006-002) from the National Science Council, the Executive Yuan of Taiwan. This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, and managed by the National Health Research Institutes. The interpretations and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, or National Health Research Institutes.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. AIDS epidemic update. http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/epidemiology/ Mar 10, 2012. http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/epidemiology/ Retrieved.

- 2.United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2010. http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/global_report.htm. Jan 18, 2012. http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/global_report.htm Retrieved.

- 3.Yang CH. Yang SY. Shen MH. Kuo HS. The changing epidemiology of prevalent diagnosed HIV infections in Taiwan, 1984–2005. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. Updated HIV/AIDS statistics in Taiwan. http://www.cdc.gov.tw/ch/ShowTopicText.ASP?TopicID=416 http://www.cdc.gov.tw/ch/ShowTopicText.ASP?TopicID=416

- 5.Frisch M. Biggar RJ. Engels EA. Goedert JJ. Association of cancer with AIDS-related immunosuppression in adults. JAMA. 2001;285:1736–1745. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiman M. Fruchter RG. Clark M. Arrastia CD. Matthews R. Gates EJ. Cervical cancer as an AIDS-defining illness. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00378-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellerbrock TV. Chiasson MA. Bush TJ, et al. Incidence of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-infected women. JAMA. 2000;283:1031–1037. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes RS. Hawes SE. Toure P, et al. HIV infection as a risk factor for cervical cancer, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in Senegal. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2442–2446. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anastos K. Hoover DR. Burk RD, et al. Risk factors for cervical precancer and cancer in HIV-infected, HPV-positive Rwandan women. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branca M. Garbuglia AR. Benedetto A, et al. Factors predicting the persistence of genital human papillomavirus infections and PAP smear abnormality in HIV-positive and HIV-negative women during prospective follow-up. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:417–425. doi: 10.1258/095646203765371321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen MJ. Wu MY. Yang JH. Chao KH. Yang YS. Ho HN. Increased frequency of genital human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive Taiwanese women. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fruchter RG. Maiman M. Sedlis A. Bartley L. Camilien L. Arrastia CD. Multiple recurrences of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women with the human immunodeficiency virus. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:338–344. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00408-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson JR. Paramsothy P. Heilig C. Jamieson DJ. Shah K. Duerr A. Accuracy of Papanicolaou test among HIV-infected women. Clinical infectious diseases: An official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006;42:562–568. doi: 10.1086/499357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan JE. Benson C. Holmes KH. Brooks JT. Pau A. Masur H. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV medicine association of the infectious diseases society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oster AM. Sullivan PS. Blair JM. Prevalence of cervical cancer screening of HIV-infected women in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:430–436. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181acb64a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taiwan Burean of Health Promotion. Annual cervical cancer screening report. 2004–2008. http://www.bhp.doh.gov.tw/bhpnet/portal/StatisticsShow.aspx?No=201003110001. Oct 4, 2010. http://www.bhp.doh.gov.tw/bhpnet/portal/StatisticsShow.aspx?No=201003110001 Retrieved.

- 17.Taiwan Center for Disease Control. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of HIV/AIDS. Taipei: Department of Health, Center for Disease Control. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bureau of National Health Insurance. National health insurance profile. 2012. http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/date_01.htm. Oct 20, 2011. http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/date_01.htm Retrieved.

- 19.Huang KH. Tsai WC. Kung PT. The use of Pap smear and its influencing factors among women with disabilities in Taiwan. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(2):307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung SD. Pfeiffer S. Lin HC. Lower utilization of cervical cancer screening by nurses in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based study. Prev Med. 2011;53(1–2):82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu CY. Hung YT. Chuang YL. Chen YJ. Weng WS. Liu JS. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manag. 2006;4:e22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dombrowski JC. Kent JB. Buskin SE. Stekler JD. Golden MR. Population-based metrics for the timing of HIV diagnosis, engagement in HIV care, and virologic suppression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;26:77–86. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834dcee9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dal Maso L. Franceschi S. Lise M, et al. Self-reported history of Pap-smear in HIV-positive women in Northern Italy: A cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:310. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahangdale L. Sarnquist C. Yavari A. Blumenthal P. Israelski D. Frequency of cervical cancer and breast cancer screening in HIV-infected women in a county-based HIV clinic in the western United States. J Women's Health. 2010;19(4):709–712. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu M. Moritz S. Lorenzetti D. Sykes L. Straus S. Quan H. A systematic review of interventions to increase breast and cervical cancer screening uptake among Asian women. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:413. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logan JL. Khambaty MQ. D'Souza KM. Menezes LJ. Cervical cancer screening among HIV-infected women in a health department setting. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(8):471–475. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim FW. Schembri G. Taha H. Ariyanayagam S. Dhar J. Cervical surveillance in HIV-positive women: A genitourinary medicine clinic experience. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2009;35(2):101–103. doi: 10.1783/147118909787931735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin HS. Wang LH. Liu SM. Kang CC. Factors associated with Papanicolaou smear practice in women in the Pingtung area. Taiwan J Public Health. 2003;22:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee TS. Fu LA. Fleming P. Using focus groups to investigate the educational needs of female injecting heroin users in Taiwan in relation to HIV/AIDS prevention. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(1):55–65. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keiser O. de Tejada BM. Wunder D, et al. Frequency of gynecologic follow-up, cervical cancer screening in the Swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:550–555. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000245884.66509.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tello MA. Yeh HC. Keller JM. Beach MC. Anderson JR. Moore RD. HIV women's health: S study of gynecological healthcare service utilization in a U.S. urban clinic population. J Women's Health. 2008;17:1609–1614. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baranoski AS. Horsburgh CR. Cupples LA. Aschengrau A. Stier EA. Risk factors for nonadherence with Pap testing in HIV-infected women. J Women's Health. 2011;20:1635–1643. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang PJ. Huang N. Chou YJ. Lee CH. Chang HJ. Determinants of the receipt of Pap smear screening under the National Health Insurance, a panel study during 1997–2000. Taiwan J Public Health. 2005;24:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrasik MP. Rose R. Pereira D. Antoni M. Barriers to cervical cancer screening among low-income HIV-positive African American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:912–925. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]