Abstract

In prostate and breast cancer, the androgen and estrogen receptors mediate induction of androgen- and estrogen-responsive genes respectively, and stimulate cell proliferation in response to the binding of their cognate steroid hormones. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) is a nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent class III histone deacetylase (HDAC) that has been linked to gene silencing, control of the cell cycle, apoptosis and energy homeostasis. In prostate cancer, SIRT1 is required for androgen-antagonist-mediated transcriptional repression and growth suppression of prostate cancer cells. Whether SIRT1 plays a similar role in the actions of estrogen or antagonists had not been determined. We report here that SIRT1 represses the transcriptional and proliferative response of breast cancer cells to estrogens, and this repression is estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα)-dependent. Inhibition of SIRT1 activity results in the phosphorylation of ERα in an AKT-dependent manner, and this activation requires phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) activity. Phosphorylated ERα subsequently accumulates in the nucleus, where ERα binds DNA ER-response elements and activates transcription of estrogen-responsive genes. This ER-dependent transcriptional activation augments estrogen-induced signaling, but also activates ER-signaling in the absence of estrogen, thus defining a novel and unexpected mechanism of ligand-independent ERα-mediated activation and target gene transcription. Like ligand-dependent activation of ERα, SIRT1 inhibition-mediated ERα activation in the absence of estrogen also results in breast cancer cell proliferation. Together, these data demonstrate that SIRT1 regulates the most important cell signaling pathway for the growth of breast cancer cells, both in the presence and the absence of estrogen.

Keywords: Sirtuin, estrogen receptor, SIRT1, ligand-independent, breast cancer

Introduction

The sirtuins are a family of enzymes with increasingly-recognized relevance to cancer (Moore 2011), but the full extent of their involvement in breast cancer genesis and evolution remains to be elucidated.

SIRT1 is a nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent histone deacetylase (HDAC) that has been linked to longevity, gene silencing, control of the cell cycle, apoptosis and energy homeostasis (Blander and Guarente 2004; Borra, et al. 2005; Dai, et al. 2007; Haigis and Guarente 2006; Landry, et al. 2000; Yamamoto, et al. 2007). SIRT1 also has functions relating to inflammation and neurodegeneration (Yamamoto et al. 2007). In addition, SIRT1 interacts with PPARγ and PGC-α in the differentiation of muscle cells, adipogenesis, fat storage and metabolism in the liver (Fulco, et al. 2003; Picard, et al. 2004; Puigserver, et al. 2005; Rodgers, et al. 2005). SIRT1 is primarily a nuclear protein that targets the PGC-1α, FOXO and NFκB families of transcription factors, among others (Haigis and Guarente 2006). SIRT1 also associates with the tumor suppressor protein p53 (Dai et al. 2007; Haigis and Guarente 2006; Yamamoto et al. 2007) and has been suggested to be a tumor suppressor protein itself (Dai et al. 2007; Jin, et al. 2007; Motta, et al. 2004; Pruitt, et al. 2006; Wang, et al. 2006).

SIRT1 appears to serve multiple functions in human prostate cancer cells. The enzyme is over-expressed in prostate cancer cells and is present in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, promoting cell survival (Byles, et al. 2010; Dai et al. 2007). However, enforced cytoplasmic localization of SIRT1 enhanced sensitivity to apoptosis in one report (Jin et al. 2007). SIRT1 also suppresses specific tumor suppressor genes in hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells (Fu, et al. 2006). Deacetylation of the androgen receptor (AR) by SIRT1 inactivates its ability to transform prostate cells. SIRT1 binds to, and deacetylates, the AR at a conserved lysine motif, down-regulating its levels in the cell and repressing androgen-induced AR transcription (Dai et al. 2007; Dai, et al. 2008). Add: (Fu et al. 2006).

SIRT1 is required for the actions of endocrine therapy in prostate cancer as well. Androgen antagonist-mediated transcriptional repression and growth suppression of prostate cancer cells requires SIRT1 (Dai et al. 2007). It had not yet been determined whether SIRT1 plays a similar role in the action of estrogen antagonists. We show here that SIRT1 is not required for estrogen antagonist activity. Rather, SIRT1 functions to repress the estrogen response in the absence and in the presence of estrogen, limiting ligand-independent signaling through ERα.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture

The MCF-7 breast cancer cell line (ATC HTB-22) is an epithelial cell line derived from an adenocarcinoma of the mammary gland. T47D cells (ATCC HTB-133) are a pTEN-negative breast cancer cell line that expresses the WNT7B oncogene. MDA-MB 231 cells (ATCC HTB-26) are an ERα-negative, estrogen-independent breast cancer cell line. All cells were cultured in phenol-red free DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) plus 10% FBS or charcoal-treated FBS (Hyclone, Erie, PA). Cells were treated with β-estradiol (R187933), sirtinol, splitomicin, 4-hydroxytamoxifen, faslodex (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (Sigma), LY294002, Wortmannin (both from CalBiochem, Gibbstown, NJ) or vehicle (EtOH or DMSO).

Transfections

Two micrograms of plasmid [ERE-luciferase reporter construct (Addgene Cambridge, MA) (Hall and McDonnell 1999); SV40-β-gal reporter construct; D/N SIRT1 (H363Y); or ERα expression vector] were added to 100 μl of OPTI-MEM (Invitrogen) and incubated for 15 min. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Luciferase Assays

The Promega Dual luciferase reporter assay system was utilized. Cellular harvest and assay were carried out according to manufacturer's instructions. Luminescence was quantitated in a Turner Designs 20/20 luminometer. Results were normalized with a β-galactosidase assay (Promega).

Immunoblot and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays

Cellular extracts were obtained by harvesting cells using lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes [pH 7.4], 10% Glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 50 mM β-glycerophophate, 1% Triton X, 1 mM Dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM Sodium Vanadate, and 1× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Scientific #04693132001). Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared using the Nu-Per kit (Thermo Scientific #78833), according to the manufacturer's instruction. Immunoblots were performed using the following antibodies. Primary antibodies used were: α-SIRT1 (Upstate Biotechnology, Waltham, MA) 1:1000; α-ERα H – 181 1:500; β-actin 1:10,000; α-β-tubulin 1:1000 (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA); α-phospho-ERα [Ser118] 1:500; α-Lamin A/C 1:1000; α-AKT 1:2000; α-phospho-AKT [Ser473] 1:2000; α-Phospho AKT [Thr308] 1:2000; FOXO3a 1:1000 (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); Secondary antibodies were as follows: α-Mouse IgG-HRP; α-Rabbit IgG-HRP (both from (GE Healthcare UK Ltd. Little Chalfont Buckinghamshire, UK). All ChIP experiments were carried out using a Fisher Scientific 550 Sonic Dismembrator for chromatin shearing, and a ChampionChIP One-Day Kit (SABiosciences #GA101) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

siRNA

siRNA transfections were carried out according to manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific Acell Smart Pool, LaFayette, CO). Cells were incubated with Smart Pool for 18 hr and then placed in media containing 10% charcoal-stripped FBS for 72 hr. Cells were then treated for 24 or 48 hr and assayed for mRNA expression via quantitative RT-PCR, or for protein expression via immunoblotting. Smart Pool sequences were as follows: siSIRT1: GUCUUAUCCUCUAGUUCUU; GCAUCUUGCCUGAUUUGUA; CUGUGAUGUCAUAAUUAAU; GUUCGGUGAUGAAAUUAUC: siERα: GAUCAAACGCUCUAAGAAG; GAAUGUGCCUGGCUAGAGA; GAUGAAAGGUGGGAUACGA; GCCAGCAGGUGCCCUACUA: siAKT: CAUCACACCACCUGACCAA; ACAAGGACGGGCACAUUAA; CAAGGGCACUUUCGGCAAG; UCACAGCCCUGAAGUACUC.

Real Time PCR

RNA was purified using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was made using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCR was carried out using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCR was carried out using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast RT-PCR machine; 50° 2′ 1 cycle: 95° 10′ 1 cycle: 95° 15″, 55° 20″, 60° 30″ 45 cycles. All primers were acquired from Invitrogen and sequences are as follows: pS2 F/R: TTGGAGCAGAGAGGAGGCAATGG; TGGTATTAGGATAGAAGCACCAGGG. SIRT1 F/R: GGAATTGTTCCACCAGCATT; AACATTCCGATGGCTTTTTG. ERα F/R:CCAGGGAAGCTACTGTTTGC; GATGTGGGAGAGGATGAGGA. β-actin F/R: 5′-GCTCGTCGTCGACAACGGCTC-3′. 5′-CAAACATGATCTGGGTCATCTTCTC-3′

Cell Proliferation Assays

2.0 × 105 cells were plated in a 6-well plate and incubated in media containing 10% charcoal-treated FBS for 48 hr. Cells were then treated as indicated and incubated for 72 hr. Viable cells were enumerated via a Trypan Blue (Invitrogen) exclusion assay on a Countess Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen).

Results

SIRT1 represses basal and inducible expression of estrogen-responsive genes

In a reporter assay using a transiently-transfected estrogen response element (ERE)-luciferase reporter construct (wherein the promoter consists of three repeats of an ERα binding motif), exposure to estrogen induced an approximately 4-fold increase in reporter activity. This induction was ameliorated by 4-hydroxy tamoxifen (4HT), an estrogen antagonist, as expected, indicating that the host MCF-7 cells are estrogen-responsive (Supplemental Fig. S1). Estrogen treatment also induced mRNA expression of pS2, an endogenous estrogen-regulated gene, approximately 5-fold, in these cells, and this induction was blocked by co-exposure to 4HT, indicating that endogenous estrogen-regulated genes are responsive to estrogen and 4HT in these cells, in a pattern similar to the reporter gene (e.g., see Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

SIRT1 is not required for estrogen-antagonist function. MCF-7 (A) or T47D (B) cells were plated to 60% confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (6 × 105 cells per dish) in C/T media and incubated for 24 hr, then exposed to vehicle, E2 (100 nM) and/or sirtinol (50 μM), 4HT (1μM) (A) and/or faslodex (100nM) (B), as indicated, incubated an additional 24 hr, and mRNA was harvested. pS2 mRNA expression was determined via quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to β-actin transcript levels. ERα protein expression was determined via immunoblot (B, inset). The data presented is the average (+/- standard error) of 6 independent experiments (A) and 3 independent experiments (B). The increases in mRNA levels induced by the treatments were significant compared to controls [p<0.001 (A) and <0.01 (B)]. Inhibition of mRNA levels by the estrogen antagonists was significant [* p<0.001 (A) and <0.01 (B)]

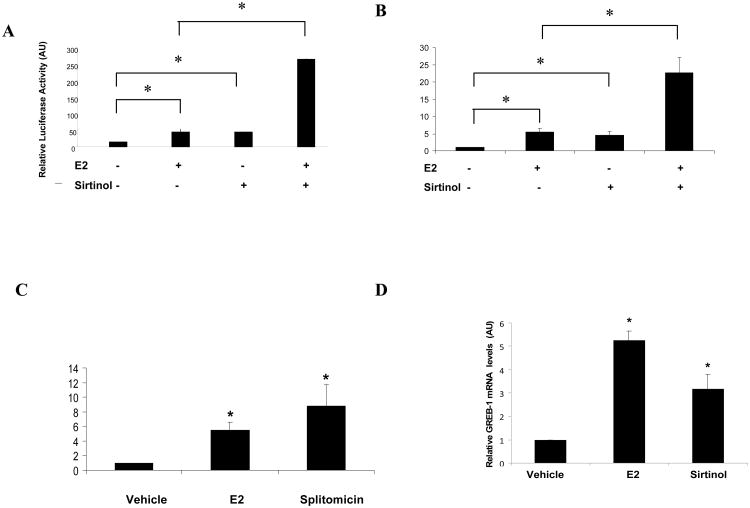

MCF-7 cells were exposed to sirtinol (Ota, et al. 2006), a small-molecule inhibitor of SIRT1 enzymatic activity, to examine the effect of SIRT1 inhibition on estrogen-regulated gene activity (Supplemental Fig. S2A). Exposure to sirtinol consistently induced the activity of a transfected estrogen-responsive reporter gene (Fig. 1A) and the mRNA levels of the endogenous pS2 gene (Fig. 1B) in the absence of estrogen. Furthermore, combining estrogen and sirtinol exposure produced a more-than-additive effect on estrogen-regulated gene activity, both for transfected and for endogenous genes (Figs. 1A and B). These results indicate that SIRT1 activity is required for basal repression of estrogen-regulated gene activity in the absence of estrogen.

Fig. 1.

SIRT1 inhibition stimulates estrogen-responsive gene activity. MCF-7 cells were plated to 60% confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (6 × 105 cells per dish) in charcoal-treated (C/T) media, incubated for 24 hr, and treated as follows: (A) transfection with an ERE-luciferase reporter plasmid and RSV confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (6 × 105 cells per dish) -β-gal, then exposed to either vehicle, or E2 (100 nM), or sirtinol (50 μM) or both, and assayed for reporter gene activity via luciferase assay. Results are normalized to β-galactosidase activity as a transfection control. In panels B, C and D, cells were exposed to either vehicle, or E2 (100 nM), or sirtinol (50 μM) or splitomicin (200 μM) or combinations thereof, and mRNA levels of the endogenous estrogen-regulated genes pS2 (B and C) and GREB-1 (D) were assayed via quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to β-actin transcript levels. The data presented is the average (+/- standard error) of 4 independent experiments. * indicates p<0.002 (A and B) and <0.01 (C and D), compared to vehicle controls. (AU: arbitrary units)

Conversely, the effects of SIRT1 activation on basal expression levels of estrogen-regulated genes was investigated via luciferase assay and by measuring endogenous ER-regulated mRNA gene expression (Supplemental Fig. S3A and B respectively) by treating MCF-7 cells with resveratrol, a phytoestrogen and an activator of SIRT1 (albeit not a specific one). SIRT1 activation via resveratrol, in conjunction with exposure with estrogen or SIRT1 inhibitors did not significantly reduce ERα transcriptional activity when compared to estrogen- or SIRT1 inhibitor-treated controls (Supplemental Fig. S3A and B).

To confirm that this effect was not restricted to sirtinol, cells were exposed in parallel studies to splitomycin (Neugebauer, et al. 2008), a chemically-distinct SIRT1 inhibitor (Supplemental Fig. S2B). SIRT1 inhibition by splitomicin induced pS2 mRNA expression levels comparably to estrogen treatment (Fig. 1C). This indicates that the induction of estrogen-responsive genes in response to SIRT1 inhibition is not a SIRT1 inhibitor-specific effect. The effects of SIRT1 inhibition on an independent, endogenous estrogen-responsive gene, GREB-1 (Carroll, et al. 2006), was assessed. Upon exposure of MCF-7 cells to estrogen or sirtinol, GREB-1 mRNA expression levels increased -5 and 4- fold, respectively (Fig. 1D), indicating that repression of estrogen-responsive genes by SIRT1 is a generalizable effect These changes in endogenous estrogen-responsive gene mRNA levels correlated with changes in estrogen-responsive luciferase reporter gene expression in the same cells, indicating that they were the result of changes in transcriptional activity.

To determine whether SIRT1 inhibition of the estrogen response is generalizable, T47D cells, an estrogen-dependent breast cancer cell line, were exposed to estrogen and/or sirtinol at varying concentrations. SIRT1 expression levels in this cell line have been previously reported (Aoyagi and Archer 2008). Estrogen induced pS2 mRNA expression levels approximately 6-fold, whereas sirtinol induced pS2 mRNA expression levels by 3-fold. Treatment with both estrogen and sirtinol increased pS2 mRNA expression more than exposure to either drug alone (e.g., see Fig. 3B). This indicates that SIRT1 inhibition of the estrogen response is not cell line-specific. Together, these data indicate that SIRT1 activity represses basal and estrogen-inducible expression of estrogen-regulated genes.

As chemical inhibitors are never completely specific with respect to their enzymatic target, more specific, genetically-based methods of inhibiting SIRT1 activity were also utilized. Cells were transfected with a dominant-negative (D/N), deacetylase-defective SIRT1 mutant, together with the ERE-luciferase reporter plasmid, to determine if the repression of estrogen-regulated gene activity is SIRT1-specific. In the absence of estrogen, expression of D/N SIRT1 induced estrogen-regulated gene activity ∼3 fold. When cells expressing D/N SIRT1 were exposed to estrogen, estrogen-regulated gene activity was induced in an additive manner (Fig. 2A). These results are consistent with the findings obtained using SIRT1 inhibitors.

Fig. 2.

Repression of estrogen-regulated gene activity is SIRT1-specific. MCF-7 cells were plated to 60% in C/T media, incubated for 24 hr, then transfected with ERE-luciferase reporter plasmid plus either empty vector or H343Y D/N SIRT and RSV-β-gal (A) or with 500 ng of scrambled siRNA or SIRT1-siRNA (B) and incubated for 18 hr, then incubated for a further 24 hr (A) or 72 hr (B) in fresh C/T media. The cells were then exposed to vehicle or E2 (100 nM), as indicated, for 24 hr. Estrogen-regulated gene activity was determined via luciferase assay normalized to β-galactosidase activity (A), or mRNA expression, as determined via quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to β-actin transcript levels (B). The efficiency of SIRT1 knockdown was determined by analyzing protein expression via immunoblot (B, inset). The data presented is the average (+/- standard error) of 3 independent experiments. * indicates p<0.005.

As another independent and specific approach, SIRT1 levels in MCF-7 cells were knocked down with SIRT1 siRNA. SIRT1 knockdown was verified by RT-PCR (data not shown) and immunoblotting (Fig. 2B). Knockdown of SIRT1 in the absence of estrogen resulted in an induction of pS2 mRNA by approximately 6-fold. pS2 induction by SIRT1 knockdown was additive in the presence of estrogen, confirming that SIRT1 represses the estrogen response in the absence and in the presence of estrogen, and that this effect is SIRT1 specific.

SIRT1 is not required for repression of estrogen-responsive genes by estrogen-antagonists

To determine whether SIRT1 is required for the function of estrogen antagonists, MCF-7 and T47D cells were exposed to estrogen in combination with sirtinol and 4HT (Fig. 3A) or faslodex (Fig. 3B), a pure estrogen antagonist. SIRT1 inhibition did not affect the ability of 4HT or faslodex to repress the estrogen response, indicating that SIRT1 is not required for estrogen antagonist function (Figs. 3A-B), in contrast to its essential role in mediating the effects of androgen antagonists (Dai et al. 2007; Dai et al. 2008).

ERα is required for regulation of estrogen-responsive genes by SIRT1 inhibition

Interestingly, 4HT and other estrogen antagonists repressed the induction of estrogen-responsive gene activity by SIRT1 inhibition as well as their induction by estrogen. One possible explanation would be that the transcriptional activation of estrogen-regulated genes observed upon SIRT1 inhibition is also dependent upon the estrogen receptor, through which 4HT and faslodex inhibit the estrogen response.

As one test of the potential dependency of SIRT1 repression of the estrogen response on ERα, MDA231 cells, which have silenced ERα expression and grow in an estrogen-independent manner, were exposed to estrogen or sirtinol. SIRT1 expression levels in this cell line have been previously reported (Alvala, et al. 2012). pS2 mRNA expression was not induced by estrogen, as expected, nor by sirtinol, compared to untreated control (data not shown, but see the empty-vector controls in Fig. 4A for a comparable experiment). ERα was then ectopically-expressed in the MDA231 cells by transfection, and the effects of exposure to estrogen or sirtinol on a co-transfected ERE-luciferase reporter gene was determined. In the absence of ERα (empty vector), neither estrogen nor sirtinol induced estrogen-regulated gene activity (Fig. 4A). However, in the presence of ERα, estrogen-regulated gene activity increased 2- to 3-fold when exposed to sirtinol or estrogen, respectively. ERα expression was verified by immunoblotting.

Fig. 4.

SIRT1 repression of estrogen-regulated gene activity is ERα-dependent. MDA231 (A) or MCF-7 (B) cells were plated to 60% confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (6 × 105 cells per dish) in C/T media, incubated for 24 hr, then transfected with an ERE-luciferase reporter plasmid plus either empty vector or an ERα-expression vector (A) or 500 ng of scrambled siRNA or ERα–specificsiRNA (B) and incubated for 18 hr, then incubated for 24 hr (A) or 72 hr (B) in fresh C/T media. The cells were then exposed to either vehicle, or E2 (100 nM), or sirtinol (50 μM), or both, as indicated, for 24 hr. Cells were then harvested and estrogen-regulated gene activity was determined via luciferase assay normalized to β-galactosidase activity (A), or mRNA expression via RT-PCR normalized to β-actin transcript levels (B). In panel A, ectopic ERα expression was verified by immunoblot (inset). In panel B, the efficiency of ERα knockdown was determined by analyzing ERα protein expression via immunoblot (inset). For panel A, the data presented is the average (+/- standard error) of 3 independent experiments. * indicates p<0.001. For panel B, the experiment was repeated five times with comparable relative ERα knockdown. In each experiment, pS2 mRNA expression levels increased in response to E2 or sirtinol treatment or the combination, and were significantly reduced in cells in which ERα had been knocked-down. A representative experiment is presented (B). * p<0.01 compared to paired black bar from scrambled siRNA-transfected cells.

To demonstrate that the observed estrogen-regulated gene activity in MDA231 cells is due to the inhibition of SIRT1, rather than a non-specific action of sirtinol, the cells were transfected with the ERE-luciferase reporter, plus or minus ERα and D/N SIRT1 expression vectors. In the absence of ERα, neither estrogen treatment nor expression of D/N SIRT1 induced estrogen-regulated gene activity. When ERα and D/N SIRT1 were expressed together, estrogen-regulated gene activity increased 15- and 20-fold, in the absence and presence of estrogen, respectively (data not shown).

As an alternative way of testing the requirement of ERα for SIRT1 activity, T47D cells were pre-treated with faslodex, a pure anti-estrogen that targets the ERα for degradation, and then exposed to estrogen, sirtinol, or both, in combination with faslodex. Pre-treatment with faslodex reduced ERα protein levels, as verified by immunoblotting (Fig. 3B). pS2 mRNA expression increased after estrogen or sirtinol exposure in vehicle-treated cells, but was this induction was abrogated in cells where the ERα had been degraded by faslodex treatment (Fig. 3B).

As a further test of the dependency of SIRT1 signaling on the ERα, knockdown of ERα by siRNA was carried out in MCF-7 cells, and the cells were then exposed to estrogen, sirtinol or both and assayed for estrogen-regulated gene induction. Knockdown of ERα was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4B) and RT-PCR (not shown). In the presence of ERα, exposure to estrogen or sirtinol caused significant induction of pS2 mRNA expression, as expected. ERα knockdown effectively blunted pS2 mRNA induction by both estrogen and sirtinol. These changes in endogenous estrogen-responsive gene mRNA levels correlated with changes in estrogen-responsive luciferase reporter gene expression in the same cells, indicating that they were the result of changes in transcriptional activity. Collectively, these findings indicate that SIRT1 repression of the estrogen-regulated gene activity in the absence and presence of estrogen is both SIRT1-specific and ERα–dependent.

Effect of SIRT1 inhibition on ERα localization

ERα is a steroid receptor that is present in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, depending upon ligand availability and the metabolic state of the cell. The nuclear fate and protein turnover of the receptor is dependent on the chemical structure of the agonist (or antagonist). Upon estrogen ligation, ERα accumulates in the nucleus. In the cell lines used throughout this study, ERα has been shown to be expressed predominately in the nucleus in cells growing in the presence of estrogen (Welsh, et al. 2012). However, ERα expressed on the cell surface as well as in the cytoplasm can be readily detected by flow cytometry as well as other analytical methods (Ford, et al. 2011). In order to determine whether SIRT1 represses ligand-independent accumulation of ERα in the nucleus, MCF-7 cells were exposed to estrogen or sirtinol, and cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared. The purity of the subcellular fractions was determined by immunoblotting with β-tubulin (a cytoplasmic protein) and Lamin A/C (a nuclear protein). In cells grown in media containing estrogen, we found that ERα was predominately expressed in the nucleus (Supplemental Fig. S4), which is in agreement with the literature. However, after 24 hours of incubation in media containing charcoal treated serum, which is devoid of all steroid hormones including estrogen, ERα was expressed predominately in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A, untreated lanes). In response to estrogen or sirtinol exposure, ERα accumulated in the nucleus (Fig. 5A), indicating that SIRT1 regulates ligand-independent ERα nuclear accumulation.

Fig. 5.

SIRT1 represses estrogen-independent ERα nuclear accumulation, promoter binding, and activation, in an AKT-dependent manner. (A) MCF-7 cells were plated to 60% confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (6 × 105 cells per dish) in C/T media and incubated for 24 hr, then exposed to vehicle, E2 or sirtinol as indicated and incubated for an additional 24 hr. The cells were then harvested and Levels of ERα protein were analyzed by immunoblotting. β-tubulin and lamin A/C were used as markers to determine the purity of the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts, respectively. The figure presented is representative of 3 independent experiments. B) MCF-7 cells were plated to 40% confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (4 × 105 cells per dish) in C/T media, incubated for 48 hr, then exposed to vehicle, E2 or sirtinol for 24 hr, harvested and ChIP analysis was performed. Immunoprecipitation was carried out using α-ERα or –Pol II antibodies (see Supplemental Fig. 3). The promoter regions of the pS2 and GREB-1 genes were amplified via quantitative PCR. The GAPDH promoter regions was also amplified, as a specificity control. The data is the average (+/- standard error) of 3 independent experiments. Immunoprecipitations carried out using non-specific antibodies or pooled antisera did not yield products up to 45 cycles of amplification (not shown). * p<0.01 compared to corresponding vehicle controls. C) MCF-7 cells were plated to 60% confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (6 × 105 cells per dish) in C/T media and incubated for 24 hr, then treated with vehicle, E2 or sirtinol as indicated, and incubated an additional 24 hr, then harvested. Protein expression levels of pERα, ERα, pAKT, AKT and β-actin were analyzed via immunoblotting. A blot representative of 3 independent experiments is shown. (* indicates a non-specific band seen even in cell lacking ERα.) D) MCF-7 cells were plated at 60% confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (6 × 105 cells per dish) in C/T media, incubated for 24 hr, then transfected with 500 ng of scrambled siRNA or AKT1-specific siRNA and incubated for 18 hr, then incubated for 72 hr in fresh C/T media. The cells were then exposed to vehicle, E2 or sirtinol for 24 hr, harvested and mRNA was collected. pS2 mRNA expression levels were determined via quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to β-actin transcript levels. The efficacy of AKT knockdown was determined by immunoblot (insert). The experiment was repeated 4 times with similar relative AKT knockdown and consistent effects on pS2 mRNA induction. Shown is a representative experiment. E) MCF-7 cells were plated to 60% confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (6 × 105 cells per dish) in C/T media, incubated for 24 hr, then exposed to vehicle, E2, or sirtinol, and/or wortmannin (100 nM) (a PI3K inhibitor), as indicated, and incubated an additional 12 hr. The cells were then harvested and protein levels of pERα, ERα and β-actin were analyzed via immunoblotting. The experiment was repeated three times with comparable results. A representative blot is shown. F) MCF-7 cells were plated to 60% confluence in a 10 centimeter dish (6 × 105 cells per dish) in C/T media and incubated for 24 hr, then exposed to vehicle, E2 or sirtinol as indicated and incubated for an additional 24 hr. The cells were then harvested and levels of FOXO3a protein were analyzed by immunoblotting. β-tubulin and lamin A/C were used as markers to determine the purity of the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts, respectively. The figure presented is representative of 3 independent experiments.

SIRT1 represses ligand-independent ERα activation and DNA binding

Once in the nucleus, ERα binds to cognate sequences on the genome and activates the transcription of estrogen-regulated genes. To determine whether SIRT1 regulates ligand-independent binding of ERα to estrogen-regulated promoters, MCF-7 cells were exposed to estrogen or sirtinol, and ERα or RNA polymerase II binding to endogenous estrogen-regulated promoters was assessed via chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. In response to estrogen, ERα association with the estrogen-regulated gene pS2 promoter increased by approximately 15-fold, as expected. Exposure to sirtinol alone also increased ERα binding to the endogenous pS2 promoter, by approximately 20-fold (Fig. 5B). To determine the generalizability of this effect, ERα binding to the promoter of another estrogen-responsive gene, GREB-1, was investigated in parallel. Estrogen or sirtinol exposure increased ERα–binding approximately 5-fold and 6–fold, respectively. In response to estrogen or sirtinol exposure, the association of RNA polymerase II with these estrogen-responsive promoters increased approximately 9- and 7-fold respectively (Supplemental Fig. S5). ERα binding to the promoter of GAPDH, a non-estrogen regulated gene, was not increased by estrogen or sirtinol.

SIRT1 represses ligand-independent ERα activation

ERα is activated by a phosphorylation event at serine118. To determine if this activating phosphorylation of ERα occurs after SIRT1 inhibition, MCF-7 cells were exposed to estrogen or sirtinol, and cell lystates were immunoblotted for phospho-ser118-ERα (pERα). In vehicle-treated cells, pERα was undetectable. Upon exposure to estrogen, pERα levels accumulated in the cell, as expected (Fig. 5C). Exposure to sirtinol alone produced a comparable rise in pERα levels. Collectively, these data indicate that SIRT1 represses ligand-independent ERα activation, nuclear localization, and binding to estrogen-regulated promoters.

SIRT1 represses estrogen-independent activation of AKT

ERα is phosphorylated at ser118 by the serine/threonine kinase AKT1 in response to estrogen. To determine whether AKT is activated in response to SIRT1 inhibition, lysates of MCF-7 cells exposed to estrogen or sirtinol were blotted for phospho-ser473-AKT1 (pAKT), the activated form of the kinase. pAKT1 was undetectable in the vehicle-treated cells. Upon exposure to estrogen, pAKT1 levels accumulated in the cell, as expected (Fig. 5C). Exposure to sirtinol alone also produced a comparable rise in activated AKT1.

To determine whether SIRT1 repression of estrogen-regulated genes is AKT1-dependent, MCF-7 cells were treated with siRNA directed against AKT1 or a scrambled siRNA, and the treated cells were then exposed to estrogen or sirtinol. In the presence of AKT1, estrogen and sirtinol increased pS2 mRNA expression approximately 12-fold (Fig. 5D). In cells where AKT1 was knocked down, neither estrogen nor sirtinol exposure increased pS2 mRNA expression. AKT1 knock-down was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 5D). Activation of estrogen-regulated genes by SIRT1 inhibition, like activation by estrogen, is therefore AKT1-dependent.

PI3K activity is required for activation of ERα signaling following SIRT1 inhibition or estrogen exposure

Activation of AKT1 occurs through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway. To determine whether the ligand-independent activation of ERα following SIRT1 repression requires the PI3K activity, as does ligand-dependent activation, MCF-7 cells were exposed to estrogen or sirtinol, in combination with wortmannin, a PI3K pathway inhibitor. In cells exposed to estrogen or sirtinol, pERα accumulated in the cell. When cells were co-treated with wortmannin, pERα was undetectable (Fig. 5E). Together, these findings suggest that SIRT1 activity may represses estrogen-independent activation AKT1 by the PI3K pathway.

SIRT1 activity is required for FOXO3a expression in the cytoplasm of breast cancer cells

The FOXO family of proteins play a role in ER signaling, as well as the regulation of PI3K activity, and are in turn regulated by SIRT1 (Zou, et al. 2008). In order to investigate the link between deregulation of the FOXO family of proteins by inhibition of SIRT1 activity and ligand-independent activation of ERα, AKT, and the PI3K pathway, MCF-7 cells were exposed to estrogen or sirtinol, and cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared. The purity of the subcellular fractions was determined by immunoblotting with β-tubulin (a cytoplasmic protein) and Lamin A/C (a nuclear protein). In untreated cells, FOXO3a was relatively evenly distributed between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. In response to estrogen or sirtinol exposure, FOXO3a disappeared from the cytoplasm (Fig. 5F), indicating that SIRT1 regulates the cytoplasmic expression of FOXO3a. Nuclear expression FOXO3a remained relatively unchanged.

SIRT1 represses estrogen-independent breast cancer cell growth

Activation of ERα by estrogen results in cellular proliferation, as well as induction of ERα-responsive genes. To determine if estrogen-independent activation of the ERα via repression of SIRT1 activity was sufficient to induce estrogen-independent proliferation, estrogen-dependent MCF-7 cells were exposed to estrogen or sirtinol for 72 hr and viable cells were enumerated. Compared to cells incubated in charcoal-stripped media, estrogen-treated cells proliferated approximately 2.5-fold over that interval. Cells exposed sirtinol alone showed comparable proliferation. Cells exposed to estrogen plus sirtinol proliferated approximately 5-fold (Fig. 6). Cell viability remained at 96-99% throughout the study.

Fig. 6.

SIRT1 inhibition induces estrogen-independent, ERα-dependent breast cancer cell proliferation. 2×105 MCF-7 cells were incubated in phenol red-free medium containing C/T serum for 24 hr, then exposed to either vehicle, estrogen (100 nM), or sirtinol (50 μM), and/or 4HT (1 μM), as indicated, for 72 hr. Viable cells were then enumerated. The data presented is the average (+/- standard error) of 4 independent experiments. Increases in cell number in response to estrogen and/or sirtinol are significant (p<0.01). * p<0.03 compared to paired open bars (vehicle-treated cells).

To determine whether this ligand-independent cell proliferation in response to SIRT1 inhibition is ERα–dependent, cells were exposed to estrogen or sirtinol in combination with 4HT, an estrogen antagonist. 4HT inhibited cell growth induced by either estrogen, or sirtinol, or the combination (Fig. 6). Collectively, these findings indicate that SIRT1 normally functions to repress estrogen-independent, ERα-dependent cell proliferation.

Discussion

These studies demonstrate that the type III histone deacetylase SIRT1 serves an important role in regulating estrogen receptor signaling. In MCF-7 cells, an estrogen-dependent breast cancer cell line, we find that SIRT1 represses the basal expression levels of estrogen-regulated genes, as well as their response to estrogen. In the absence of estrogen, SIRT1 repression by small molecule inhibitors or a dominant-negative SIRT1, or siRNA knockdown, induces estrogen-regulated gene activity to a level comparable to the induction seen when the cells are exposed to estrogen. When SIRT1 is inhibited by various independent means in the presence of estrogen, estrogen-regulated gene activity is induced in an additive manner. These results are generalizable, and the effects are specific for SIRT1, as they are recapitulated by the specific genetic techniques of siRNA knockdown of SIRT1 or expression of a dominant-negative SIRT1. Interestingly, and in contrast to its function in androgen signaling (Dai et al. 2007), SIRT1 is not required for estrogen antagonist activity.

The repression of estrogen-regulated genes by SIRT1 is dependent upon the ERα as demonstrated by a number of independent approaches. 4HT and faslodex, which serve as ER-ligand antagonists, are able to suppress the induction of estrogen-responsive genes produced by inhibition of SIRT1, both in the presence and absence of estrogen. Furthermore, MDA231 cells, which lack ERα, do not show induction of ER-regulated genes upon exposure to SIRT1 inhibitors (or to estrogen). When ERα is ectopically-expressed in MDA231 cells, however, SIRT1 inhibition stimulates the induction estrogen-responsive genes.

Ligand-independent activation of estrogen-responsive genes by SIRT1 inhibitors shares a number of common elements with ligand (estrogen)-dependent activation signaling. SIRT1 inhibition results in ligand-independent phosphorylation and activation of ERα, accumulation of phospho-ERα in the nucleus, and subsequent association of ERα with the promoters of estrogen-responsive genes, in a pattern similar to that induced by estrogen.

ERα is known to be acetylated at multiple sites in vivo (Wang, et al. 2001). Mutational modification of certain of these acetylation sites may modestly influence the activity of the receptor, raising the possibility that the deacetylase SIRT1 might act on ERα directly, through modulation of ERα acetylation status. Furthermore, the deacetylase activity of SITR1 is required for its effects on ERα signaling, as the dominant-negative SIRT1 mutant we utilized is deacetylase-deficient. We found, however, that the PI3K/AKT pathway is required for ligand-independent activation of ERα following SIRT1 inhibition, just as it is for activation by estrogen, indicating that the actions of SIRT1 on ERα are likely indirect, rather than direct. Thus, SIRT1 inhibitors subvert the same pathway for ligand-independent activation of the ERα that estrogen utilizes for ligand-dependent activation.

Under normal conditions, SIRT1 appears to repress ERα-mediated cell growth when estrogen is absent, blocking estrogen-independent breast cancer cell proliferation. Inhibition of SIRT1 activity allows proliferation in the absence of estrogen. This proliferation can be blocked by estrogen antagonists, indicating that this proliferation, like the induction of estrogen-regulated genes, is dependent upon ERα.

A link between SIRT1 activity and the repression of estrogen-independent estrogen receptor-signaling has not been previously established. However, a recent report indicates that within the nucleus, SIRT1 co-localizes and binds with ERα in several breast and breast cancer cell lines (Elangovan, et al. 2011). One possible model is that SIRT1 may be inhibiting ERα, PI3K or AKT activation directly. However, any direct link between SIRT1 and PI3K regulation, with subsequent downstream effects on AKT-activity, or functionally-related acetylation of p85, p110 and AKT has not been identified to date. Furthermore, while ERα-SIRT1 binding requires SIRT1 catalytic activity, SIRT1 does not affect the acetylation status of ERα (Elangovan, et al. 2011). We speculate instead that SIRT1 regulation of ERα and PI3K/AKT activity is more likely carried out in an indirect manner, through co-regulatory proteins.

One potential co-regulatory protein is phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) (Ikenoue, et al. 2008; Maehama and Dixon 1998; Myers, et al. 1998; Stambolic, et al. 1998). SIRT1 deacetylates PTEN at L402, thereby inactivating PTEN and relieving repression of PI3K signaling (Ikenoue et al. 2008). However, our studies show an increase in PI3K signaling (AKT phosphorylation) in response to SIRT1 inhibition, so it is unlikely that PTEN plays a role in SIRT1-mediated repression of estrogen-independent PI3K activity.

The FOXO family of proteins play a role in ERα signaling, as well as the regulation of PI3K activity, and are in turn regulated by SIRT1. Much of the activity seen in MCF-7 cells when FOXO family members are inhibited mirrors the findings of this report. For example, the silencing of endogenous FOXO3a increases expression of estrogen-regulated genes and can convert non-tumorigenic, estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells into tumorigenic, estrogen-independent cells (Zou et al. 2008). Herein, we report that SIRT1 catalytic activity is required to maintain FOXO3a expression in the cytoplasm. We hypothesize that it is this maintenance of FOXO3a expression and activity in the cytoplasm that prevents FOXO3a from becoming disassociated with ERα in the absence of ligand, thereby preventing the ligand-independent activation of ERα, transcription of estrogen-regulated genes and breast cancer cell proliferation (Fig. 7). We are currently further investigating a link between deregulation of the FOXO family of proteins by inhibition of SIRT1 activity and ligand-independent activation of ERα, AKT, and the PI3K pathway.

Fig. 7. Model of SIRT1 repression of ligand-independent ERα activation.

A) Normal estrogen signaling. Estrogen (E2) enters the cell and binds to ERα in the cytoplasm (1). This activates PI3K which phosphorylates AKT [long red arrow] (2). This in turn phosphorylates ERα (3) which then translocates to the nucleus [large black arrow] (4), where it recruits cofactors and other transcriptional machinery, induces ER-regulated genes and leads to cancer cell proliferation. SIRT1 and FOXO3a act as tonic inhibitors of ERα and PI3K in the presence of E2, as is demonstrated by the fact that SIRT1 inhibition in addition to E2 treatment yields additive induction of ER-regulated genes [dashed red arrow and black line]. B) SIRT1 inhibition in the absence of E2. SIRT1 stabilizes FOXO3a in the cytoplasm through SIRT1 deacetylase activity [small red arrow] (1) which in turn represses ligand-independent ERα, PI3K and AKT activation [solid black line] (2 and 3). The ERα does not translocate to the nucleus (4) and is not degraded in the cytoplasm via the proteosome. ER-regulated genes are not induced nor does the cell proliferate. C) Effect of SIRT1 inhibition on ligand-independent ERα activation. SIRT1 inhibition (1) destabilizes FOXO3a cytoplasmic localization, which relieves ligand-independent repression of PI3K and ERα (2). This leads to PI3K-mediated activation of AKT which in turn phosphorylates and activates ERa (3). ERα translocates to the nucleus where it recruits co-factors and transcriptional machinery and initiates transcription of ER-regulated genes, leading to cancer cell proliferation (4). Due to a lack of E2 ligation, ERα is not degraded via the proteosome.

The findings presented in this report differ from those of several previous reports. Other studies have found that sirtuin inhibition results in cell death and p53 acetylation (Peck, et al. 2010), or cell senescence (Ota et al. 2006), or that it represses expression levels of ERα (Yao, et al. 2010). Elangovan et al. suggests that SIRT1 is required for oncogenic signaling in breast cancer cells. Furthermore, Yao, et al. indicated that SIRT1 inhibition decreases levels of ERα protein expression. Those studies differ from this report in one major way, namely, the previously mentioned studies did not starve the breast cancer cells of steroid hormones prior to SIRT1 inhibition. Rather, SIRT1 was inhibited while the breast cancer cells were growing logarithmically in the presence of estrogen with ERα engaged by estrogen ligand. In the present study, however, cells were incubated in charcoal-treated media, thereby depriving the cells of any steroidal hormone signaling, disengaging the Ras-MAPK pathway (Ota et al. 2006), halting cell growth without effects on cell viability (as shown in Fig. 6), and allowing study of the effects of SIRT1 depletion on quiescent cells with unengaged ERα. The Ras-MAPK pathway (Ota et al. 2006), as well as p53 (Peck et al. 2010) may contribute to differential regulation of estrogen signaling by SIRT1 in the presence or absence of hormonal signaling. Another methodological difference between our approach and some of the papers cited above is our use of reagents highly-specific for SIRT1 (shRNA and dominant-negative proteins) to confirm the role of SIRT1 rather than relying only on chemical inhibitors, which target SIRT2 as well as having other off-target effects. (Peck et al. 2010) showed that the effects they observed of SIRT inhibitors on p53 and cell death required inhibition of both SIRT1 and SIRT2. Lastly, as shown in Fig. 5A, C and E, we did not detect any significant change in ERα protein expression in response to the experimental conditions presented herein. The data presented here therefore highlight a potentially significant difference between the regulation of estrogen receptor signaling in the presence of estrogen compared with ligand-independent signaling in the absence of estrogen. The results presented here, therefore, describe an important mechanism by which breast cancer cells might transition from an estrogen-dependent to an estrogen-refractory state, particularly in the setting of estrogen depletion or estrogen antagonists.

The findings presented in this report support the concept that SIRT1 serves as a tumor suppressor gene in breast cancer cells (Jin et al. 2007; Moore 2011). These findings also highlight the potential role of SIRT1 in regulating breast cancer cell dependency upon estrogen.

When coupled with the findings that SIRT1 increases the expression of drug-resistance genes (Chu, et al. 2005), SIRT1 may have the potential to be an important biomarker for breast cancer prognosis or future patient-specific tailored chemotherapeutic strategies (Bhat-Nakshatri, et al. 2008; Chu et al. 2005). Similarly, modulation of SIRT1 activity may prove useful for next-generation breast cancer therapeutics.

In view of the major regulatory effects of SIRT1 on ERα signaling in breast cancer, further study of the transcriptional and post-translational regulation of SIRT1 in breast cancer cells will likely prove relevant to our understanding of the genesis of breast cancer, and its evolution to a hormone-independent state.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute, R01-CA101992 (DVF) and CA101992S1 (RM), and by the Karin Grunebaum Cancer Research Foundation (DVF). We thank Dr. Yan Dai for reagents and advice, and Ms. Lora Forman for technical advice (all at Boston University).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alvala M, Bhatnagar S, Ravi A, Jeankumar VU, Manjashetty TH, Yogeeswari P, Sriram D. Novel acridinedione derivatives: Design, synthesis, SIRT1 enzyme and tumor cell growth inhibition studies. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2012;22:3256–3260. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi S, Archer TK. Nicotinamide uncouples hormone-dependent chromatin remodeling from transcription complex assembly. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28:30–39. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01158-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat-Nakshatri P, Wang GH, Appaiah H, Luktuke N, Carroll JS, Geistlinger TR, Brown M, Badve S, Liu YL, Nakshatri H. AKT Alters Genome-Wide Estrogen Receptor alpha Binding and Impacts Estrogen Signaling in Breast Cancer. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28:7487–7503. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00799-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blander G, Guarente L. The Sir2 family of protein deacetylases. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2004;73:417–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borra MT, Smith BC, Denu JM. Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:17187–17195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byles V, Chmilewski LK, Wang J, Zhu L, Forman LW, Faller DV, Dai Y. Aberrant cytoplasm localization and protein stability of SIRT1 is regulated by PI3K/IGF-1R signaling in human cancer cells. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:599–612. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Meyer CA, Song J, Li W, Geistlinger TR, Eeckhoute J, Brodsky AS, Keeton EK, Fertuck KC, Hall GF, et al. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nature Genetics. 2006;38:1289–1297. doi: 10.1038/ng1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu F, Chou PM, Zheng X, Mirkin BL, Rebbaa A. Control of multidrug resistance gene mdr1 and cancer resistance to chemotherapy by the longevity gene sirt1. Cancer Research. 2005;65:10183–10187. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Ngo D, Forman LW, Qin DC, Jacob J, Faller DV. Sirtuin 1 is required for antagonist-induced transcriptional repression of androgen-responsive genes by the androgen receptor. Molecular Endocrinology. 2007;21:1807–1821. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Ngo D, Jacob J, Forman LW, Faller DV. Prohibitin and the SWI/SNF ATPase subunit BRG1 are required for effective androgen antagonist-mediated transcriptional repression of androgen receptor-regulated genes. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1725–1733. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elangovan S, Ramachandran S, Venkatesan N, Ananth S, Gnana-Prakasam JP, Martin PM, Browning DD, Schoenlein PV, Prasad PD, Ganapathy V, et al. SIRT1 Is Essential for Oncogenic Signaling by Estrogen/Estrogen Receptor alpha in Breast Cancer. Cancer Research. 2011;71:6654–6664. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CHJ, Al-Bader M, Al-Ayadhi B, Francis I. Reassessment of Estrogen Receptor Expression in Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Anticancer Research. 2011;31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu MF, Liu MR, Sauve AA, Jiao XM, Zhang XP, Wu XF, Powell MJ, Yang TL, Gu W, Avantaggiati ML, et al. Hormonal control of androgen receptor function through SIRT1. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26:8122–8135. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00289-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulco M, Schiltz RL, Iezzi S, King MT, Zhao P, Kashiwaya Y, Hoffman E, Veech RL, Sartorelli V. Sir2 regulates skeletal muscle differentiation as a potential sensor of the redox state. Molecular Cell. 2003;12:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigis MC, Guarente LP. Mammalian sirtuins - emerging roles in physiology, aging, and calorie restriction. Genes & Development. 2006;20:2913–2921. doi: 10.1101/gad.1467506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JM, McDonnell DP. The estrogen receptor beta-isoform (ER beta) of the human estrogen receptor modulates ER alpha transcriptional activity and is a key regulator of the cellular response to estrogens and antiestrogens. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5566–5578. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikenoue T, Inoki K, Zhao B, Guan KL. PTEN acetylation modulates its interaction with PDZ domain. Cancer Research. 2008;68:6908–6912. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin QH, Yan TT, Ge XJ, Sun C, Shi XG, Zhai QW. Cytoplasm-localized SIRT1 enhances apoptosis. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2007;213:88–97. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry J, Slama JT, Sternglanz R. Role of NAD(+) in the deacetylase activity of the SIR2-like proteins. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;278:685–690. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RL. Sirtuin (SIRT) 1 and Steriod Hormone Activity in Cancer. In: Dai Y, editor. Journal of Endocrinology. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motta MC, Divecha N, Lemieux M, Kamel C, Chen D, Gu W, Bultsma Y, McBurney M, Guarente L. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116:551–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MP, Pass I, Batty IH, Van der Kaay J, Stolarov JP, Hemmings BA, Wigler MH, Downes CP, Tonks NK. The lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN is critical for its tumor suppressor function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:13513–13518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer RC, Uchiechowska U, Meier R, Hruby H, Valkov V, Verdin E, Sippl W, Jung M. Structure-activity studies on splitomicin derivatives as sirtuin inhibitors and computational prediction of binding mode. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;51:1203–1213. doi: 10.1021/jm700972e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota H, Tokunaga E, Chang K, Hikasa M, Iijima K, Eto M, Kozaki K, Akishita M, Ouchi Y, Kaneki M. Sirt1 inhibitor, Sirtinol, induces senescence-like growth arrest with attenuated Ras-MAPK signaling in human cancer cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:176–185. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck B, Chen CY, Ho KK, Di Fruscia P, Myatt SS, Coombes RC, Fuchter MJ, Hsiao CD, Lam EWF. SIRT Inhibitors Induce Cell Death and p53 Acetylation through Targeting Both SIRT1 and SIRT2. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2010;9:844–855. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard F, Kurtev M, Chung NJ, Topark-Ngarm A, Senawong T, de Oliveira RM, Leid M, McBurney MW, Guarente L. Sirt1 promotes fat mobilization in white adipocytes by repressing PPAR-gamma. Nature. 2004;429:771–776. doi: 10.1038/nature02583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt K, Zinn RL, Ohm JE, McGarvey KM, Kang SHL, Watkins DN, Herman JG, Baylin SB. Inhibition of SIRT1 reactivates silenced cancer genes without loss of promoter DNA hypermethylation. Plos Genetics. 2006;2:344–352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver P, Rodgers J, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi S, Spiegelman B. Nutrient control of glucose metabolism through PGC-1?/SIRT1 complex. Gerontologist. 2005;45:56–56. doi: 10.1038/nature03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1 alpha and SIRT1. Nature. 2005;434:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Brothers GM, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T, Ruland J, Penninger JM, Siderovski DP, Mak TW. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 1998;95:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CG, Chen LH, Hou XH, Li ZY, Kabra N, Ma YH, Nemoto S, Finkel T, Gu W, Cress WD, et al. Interactions between E2F1 and SirT1 regulate apoptotic response to DNA damage. Nature Cell Biology. 2006;8:1025–U1109. doi: 10.1038/ncb1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CG, Fu MF, Angeletti RH, Siconolfi-Baez L, Reutens AT, Albanese C, Lisanti MP, Katzenellenbogen BS, Kato S, Hopp T, et al. Direct acetylation of the estrogen receptor alpha hinge region by p300 regulates transactivation and hormone sensitivity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:18375–18383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh AW, Lannin DR, Young GS, Sherman ME, Figueroa JD, Henry NL, Ryden L, Kim C, Love RR, Schiff R, et al. Cytoplasmic Estrogen Receptor in Breast Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2012;18:118–126. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J. Sirtuin functions in health and disease. Molecular Endocrinology. 2007;21:1745–1755. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Li HZ, Gu YS, Davidson NE, Zhou Q. Inhibition of SIRT1 deacetylase suppresses estrogen receptor signaling. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:382–387. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou YY, Tsai WB, Cheng CJ, Hsu C, Chung YM, Li PC, Lin SH, Hu MCT. Forkhead box transcription factor FOXO3a suppresses estrogen-dependent breast cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Breast Cancer Research. 2008;10 doi: 10.1186/bcr1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.